Abstract

Background

Human follicular fluid (HFF) provides a key environment for follicle development and oocyte maturation, and contributes to oocyte quality and in vitro fertilization (IVF) outcome.

Methods

To better understand folliculogenesis in the ovary, a proteomic strategy based on dual reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) coupled to matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MALDI TOF/TOF MS) was used to investigate the protein profile of HFF from women undergoing successful IVF.

Results

A total of 219 unique high-confidence (False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.01) HFF proteins were identified by searching the reviewed Swiss-Prot human database (20,183 sequences), and MS data were further verified by western blot. PANTHER showed HFF proteins were involved in complement and coagulation cascade, growth factor and hormone, immunity, and transportation, KEGG indicated their pathway, and STRING demonstrated their interaction networks. In comparison, 32% and 50% of proteins have not been reported in previous human follicular fluid and plasma.

Conclusions

Our HFF proteome research provided a new complementary high-confidence dataset of folliculogenesis and oocyte maturation environment. Those proteins associated with innate immunity, complement cascade, blood coagulation, and angiogenesis might serve as the biomarkers of female infertility and IVF outcome, and their pathways facilitated a complete exhibition of reproductive process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In vitro fertilization (IVF) coupled with embryo transfer into uterus has been applied as treatment for infertility several decades. IVF was initially used to assist the reproduction of sub-fertile women caused by tubal factors [1]. With the improvement of IVF techniques, IVF is now a routine treatment for many reproductive diseases. However, the success rate of pregnancy is still a problem in clinical IVF practice, which is only about 50% even if the embryos with normal morphology were used for transfer [2]. In order to select embryos with the best potential good for IVF outcome, morphological assessments of blastocyst and blastocoels have been adopted, but it was still difficult to predict the quality of embryos [3]. Therefore, it was necessary to develop new strategies for embryo quality evaluation. Epidemiologic investigations showed that many intrinsic and extrinsic factors contributed to the quality of embryo. Because oocyte quality directly influences embryo development, HFF (microenvironment of oocyte maturation) became a main factor contributing to the success of IVF treatment [4].

Small antral follicles respond to ovarian stimulation by increasing in size due to rapid accumulation of follicular fluid, as well as granulosa cell divisions, which necessitate follicular basal lamina expansion. The components of HFF had several origins: secretions from granulosa cells, thecal cells, occytes, and blood plasma composition transferred through the thecal capillaries [5]. The major components of HFF were proteins [6], steroid hormones [7], and metabolites [8]. HFF provided a special milieu to facilitate the communications between occyte and follicular cells, the development of follicle and the maturation of occytes. The alteration of HFF proteins reflected disorders of main secretary function of granulosa cells and thecae, and the damage of blood follicular barrier, which was associated with abnormal folliculogenesis [9] and a diminished reproductive potential [10]. In IVF treatment, HFF was easily accessible during the aspiration of oocytes from follicle, and was an ideal source for noninvasive screening of biomakers for oocyte maturation, fertilization success, IVF outcome, pregnancy, and ovarian diseases.

In the postgenomic era, proteomic techniques have been widely used in the field of reproductive medicine. HFF proteome has become a hotspot for research, which not only contributed to discovering proteins related to IVF outcomes, but also improved our comprehensive understanding of physiological process during follicle development and oocyte maturation [11]. Li and co-workers used surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry (SELDI-TOF-MS) combined with weak cation-exchange protein chip (WCX-2) to search for differentially expressed HFF proteins from mature and antral follicles [12]. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2D–GE) followed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) was also used to identify 8 differentially expressed HFF proteins related to immune and inflammatory responses from controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) and natural ovulatory cycles [13]. Ambekar and co-workers carried out SDS-PAGE, OFFGEL and SCX-based separation followed by LC-MS/MS analysis to characterize 480 HFF proteins for a better understanding of folliculogenesis physiology [14]. Chen and co-workers explored the HFF biomarkers between successfully fertilized oocytes and unfertilized mature oocytes through nano-scale liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (nano LC-MS/MS), and found 53 peptides to be potential candidates [15]. Although proteomic researches on HFF deepened our understanding of reproductive process and provided candidates related to oocyte quality, follicle development, IVF outcome and ovarian disorders, it was still essential to fully delineate the HFF networks and pathways involved in the physiology of reproduction and pathophysiology of infertility.

In the present study, we carried out an in-depth proteomic analysis of HFF from women undergoing successful IVF based on dual RP-HPLC coupled to MALDI TOF/TOF MS. The results profiled candidate biomarkers for the prediction of oocyte maturation, fertilization, and pregnancy and provided a new complement for HFF dataset, which will improve the understanding of biological processes and complicated pathways and interaction networks in HFF.

Methods

Patients enrollment and sample preparation

The HFF samples were collected from 10 women who underwent IVF treatment and achieved pregnancy. The selected patients met the following criteria: infertility not caused by tubal factor; aged less than 38 years; serum FSH values <12 mIU/mL; undergoing their first fresh egg retrieval cycle; ovulation stimulated with the long protocol. The patients were also without chromosomal abnormalities, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis and or endocrine disease. Cause of infertility was simple male factor. The body mass index (BMI) of patients met the normal criteria proposed by WGOC (18.5 ≤ BMI ≤ 23.9 kg/m2) [16,17,18]. Ovarian stimulation and oocyte retrieval were performed as previously described [19]. Briefly, when more than two follicles exceeded 18 mm in diameter, 10,000 IU of HCG (Merck Serono, Swiss) was injected intramuscular. After 36 h, HFF was collected during trans-vaginal ultrasound guided aspiration of oocytes. The resultant HFF samples were macroscopically clear and without contamination of the flushing medium.

The samples were centrifuged at 10,000×g at 4 °C for 30 min to produce cell debris-free HFF fraction for further analysis. Concentration of HFF was determined by the Bradford method [20]. This work has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing BaoDao Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, and written informed consents were obtained from all participants.

First dimension high pH RP chromatography

Equal amounts (50μg) of HFF proteins from each sample were pooled for separation. The samples were sequentially treated with 20 mM dithiothreitol at 37 °C for 120 min, and 50 mM iodoacetamide in dark for 60 min at room temperature. Then the sample was finally digested using trypsin (sequencing grade, Promega, France) (W/W, 1:50 enzyme/protein) overnight at 37 °C. According to the previous method with appropriate modification [21], the first dimension RP separation was performed on PF-2D HPLC System (Rigol) by using a Durashell RP column (5 μm, 150 Å, 250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d., Agela). Mobile phases A (2% acetonitrile, adjusted pH to 10.0 using NH3.H20) and B (98% acetonitrile, adjusted pH to 10.0 using NH3.H20) were used to develop a gradient. The solvent gradient was set as follows: 5% B, 5 min; 5–15% B, 15 min; 15–38% B, 15 min; 38–90% B, 1 min; 90% B, 8.5 min; 90–5% B, 0.5 min; 5% B, 10 min. The tryptic peptides were separated at an eluent flow rate of 0.8 ml/min and monitored at 214 nm. Totally, 28 eluent fractions were collected and dried by a SPD2010 SpeedVac concentrator system (Thermo, USA).

Second dimension low pH RP chromatography coupled with MS/MS measurement

According to the previous method [22], the samples were dried under vacuum and reconstituted in 30 μl of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid, 2% (v/v) acetonitrile in water for subsequent analyses. Each fraction was separated and spotted using the Tempo™ LC-MALDI Spotting System (AB SCIEX, USA). Peptides were separated by a C18 AQ 150 × 0.2 mm column (3 μm, Michrom, USA) using a linear gradient formed by buffer A (2% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) and buffer B (98% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid), from 5% to 35% of buffer B over 90 min at a flow rate of 0.5 μL/min. The eluted peptides were mixed with matrix solution (5 mg/mL in 70% acetonitrile, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) at a flow rate of 2 μL/min pushed by additional syringe pump. For each fraction, 616 spots were spotted on a 123× 81 mm LC-MALDI plate insert. Then the spots were analyzed using MALDI-TOF/TOF 5800 mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, USA). A full-scan MS experiment (m/z range from 800 to 4000) was acquired, and then the top 40 ions were detected by MS/MS.

Protein identification

Protein identification was performed with the ProteinPilot™ software (version 4.0.1; AB SCIEX). Each MS/MS spectrum was searched against a database (2017_03 released UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot human database, 20,183 entries) and a decoy database for FDR analysis (programmed in the software). The search parameters were as follows: trypsin enzyme; maximum allowed missed cleavages 1; Carbamidomethyl cysteine; biological modifications programmed in the algorithm. Proteins with high-confidence (FDR < 0.01) were considered as positively identified proteins.

Bioinformatics

The gene ontology enrichment analysis of HFF proteins were performed by using online bioinformatics tools of PANTHER (Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships) classification system (released 11.1, 2016–10-24) (http://pantherdb.org/) [23] and DAVID (The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery) bioinformatics resources 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) [24]. Each protein was placed in only one category, and those with no annotation and supporting information were categorized as “Unknown”. The pathway map of HFF proteins were achieved through KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (Release 81.0, 2017–01-01) (http://www.kegg.jp) [25]. The protein-protein interaction network for the HFF proteins was annotated using the STRING (search tool for recurring instances of neighbouring genes) database (released 10.0, 2016–04–16) (http://string-db.org/) [26]. The venn diagram was drawn through a online software “Calculate and draw custom Venn diagrams” (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/).

Western blot analysis

According to the method described previously [27, 28], 50 μg HFF protein were separated by a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and then electronically transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The resultant membrane was blocked with 5% (w/v) skimmed milk for 1 h at 37 °C, and then was incubated with the primary antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, USA, diluted 1:2000) at 4 °C overnight. After washing with TBST for three times, the membranes were incubated with horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (diluted 1:5000, Zhong-Shan Biotechnology, Beijing, China) at room temperature for 1 h. The immunoreactive proteins was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Results

Identification of high-confidence HFF proteome by dual RP-HPLC coupled with MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectrometry.

A peptide sequencing strategy was applied by using two-dimensional chromatography-MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. We employed high pH (pH 10) reverse phase liquid chromatography to decrease the complexity of the tryptic digest of the HFF proteins, and collected 28 fractions. Then each fraction was further separated by low pH (pH 3) reverse phase liquid chromatography, and spotted on the plate using the Tempo™ LC-MALDI Spotting System. After sequencing by a 5800 MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectrometry, the resultant spectra were analyzed by ProteinPilot™ software by searching the reviewed Swiss-Prot human database (20,183 sequences, 2017_03 released). A total of 219 unique high-confidence (FDR < 0.01) proteins were identified by two replicates (Table 1). Experiment 1 and 2 identified 188 with 2747 unique peptides and 179 proteins with 2800 unique peptides, respectively. 148 common proteins were shared between the two experiments. Figure 1 showed representative MS/MS spectra of peptides from the identified HFF proteins. The m/z of precursor (Fig. 2c) was over 2500, and almost all b-ions and y-ions were still obtained based on a 5800 MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectrometry.

Identification of HFF proteins by LC MALDI TOF/TOF MS Spectra. The MS/MS map (a, b) marked with b ions and y ions for vitamin D-binding protein identification. The sequences of precursor at m/z 2053.8506 and 2353.9646 were analyzed by MS/MS to be GQELCADYSENTFTEYK and SYLSMVGSCCTSASPTVCFLK and the protein identified as vitamin D-binding protein. The MS/MS map (c, d) marked with b ions and y ions for retinol-binding protein 4 identification. The sequences of precursor at m/z 2692.0667 and 1197.6047 were analyzed by MS/MS to be GNDDHWIVDTDYDTYAVQYSCR and YWGVASFLQK and the protein identified as retinol-binding protein 4

Bioinformatics analysis of the HFF proteome

The proteins identified by mass spectrometry were broadly placed into several GO categories on the basis of the PANTHER, DAVID and PubMed databases (Fig. 2). Based on molecular function, the majority (31%) of proteins were related to immunity, whereas other involved protein functions were mainly complement and coagulation (17%), protease or inhibitor (14%), and transportation (10%) (Fig. 2a). Based on subcellular localization, the majority (64%) of the identified proteins located in extracellular region. Other main locations were extracellular matix (7%), nuleus (6%), and cytoskeleton (5%) (Fig. 2b). Based on biological process, the majority (28%) of proteins was related to developmental process, and the next prevalence was immunological system process (26%). The other groups were involved into protein metabolic process (12%), reproduction (5%), lipid metabolic process (3%), and transportation (2%) (Fig. 2c).

KEGG pathway analysis was performed to map HFF protein interactions, Pathways associated with complement and coagulation cascades (P_Value = 5.8E-52), vitamin digestion and absorption (P_Value = 0.023), and (P_Value = 0.066) were significantly enriched. Figure 3 showed the complement and coagulation cascades pathway which included 17 (7.8%) and 21 (9.6%) highlighted HFF proteins in coagulation cascade and complement cascade, respectively.

Presentative Network of protein HSPG2 in the identified HFF proteome. A total of 21 genes are connected with 105 paired relationships annotated by STRING database. The relationships among proteins were derived from evidence that includes textmining, co-expression, protein homology, gene neighborhood, from curated databases, experimentally determined, gene fusions, and gene co-occurrence (as shown in the legend with different color)

A protein-protein interaction network was constructed by retrieving the STRING database. 151 proteins were in connection with other proteins, which lead to 738 paired relationships. As an example, 21 of 151 proteins related to basement membrane-specific heparan sulfate proteoglycan core protein (HSPG) was chosen, and 105 paired relationships were connected (Fig. 4).

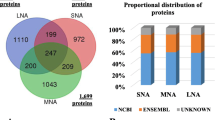

Comparison of present HFF proteome, the previous reported HFF proteome and human plasma proteome

To disclose the overlap of the HFF proteomes between different labs and to explore the orign of the HFF proteins, the previous reported HFF proteins [14] and the human plasma proteome [29] were selected, whose protein identification criteria were both at a false discovery rate (FDR) of 1%. The results reflected the overlap of our HFF proteins and the previously reported HFF proteins with human plasma proteins (Fig. 5). A total of 49% proteins in our HFF data were common to the previous HFF data. Compared with human plasma proteins, 69% proteins from our HFF data and 64% proteins from previous HFF data were common to human plasma proteins.

Western blotting analysis

To verify the confidence of the proteome data, the expression patterns of 3 HFF proteins (retinol-binding protein 4, vitamin D-binding protein and lactotransferrin) from 10 women undergoing successful IVF were analyzed by western blotting (Fig. 6). Those three proteins could be detected in all 10 HFF samples. Compared with retinol-binding protein 4 and lactotransferrin, the expression of vitamin D-binding protein was relatively constant level in the HFF of ten women.

Immunoblot analysis of retinol-binding protein 4, vitamin D-binding protein and lactotransferrin in 10 HFF samples of women underwent successful IVF. Protein lysates prepared from 10 HFF samples were examined by immunoblots using specific antibodies recognizing the retinol-binding protein 4(23 kDa), vitamin D-binding protein (53 kDa) and lactotransferrin (78 kDa)

Discussion

Proteomics has been carried out to discover HFF biomarkers for decades, and liquid chromatography coupled with ion trap MS became widely available with the development of high-throughput sequencing. The identification of HFF proteins from women with and without endometriosis was performed using ESI MS/MS [30]. Nanoflow LC-MS/MS combined with TMT labeling was used to identify HFF biomarkers from women undergoing IVF/ICSI treatment with or without folic acid supplement [31]. Another advance LTQ Orbitrap system coupled with LC was also applied to comparing HFF proteins between fertilized oocytes and non-fertilized oocytes from the same patient [32]. Based on sample pre-fractionation using microscale in-solution isoelectric focusing (IEF), capillary electrophoresis (CE) coupled off-line to matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight tandem mass spectrometry (MALDI TOF MS/MS) identified 73 unique proteins [33]. Hanrieder and co-workers [34] utilized a proteomic strategy of IEF and reversed-phase nano-liquid chromatography coupled to MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectrometry to identify 69 proteins related to controlled ovarian hyper stimulation (COH) during IVF. However, limited proteins were identified which delayed the research of HFF protein networks.

In the present work, a dual RP-HPLC coupled with MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectrometry was performed to identify HFF protein profiles associated with successful IVF, and 219 unique high-confidence (FDR < 0.01) HFF proteins were identified by searching the reviewed Swiss-Prot human database (20,183 sequences). Meanwhile, the new strategy indicated that the effective dual reverse LC pre-fractionation [21] could identify more HFF proteins.

Ambekar and co-workers carried out SDS-PAGE, OFFGEL and SCX-based separation followed by LC–MS/MS (an LTQ-Orbitrap Velos MS) to identify 480 HFF proteins with high confidence (FDR < 0.01) [14]. A comparison with our results and these data showed that more than 50% proteins in present study were not found in previous dataset (Additional file 2: Figure S1), which indicated that the data from different MS platforms were complementary. Retinol-binding protein 4 and vitamin D-binding protein were verified by western blotting, and the results showed they were all expressed in the 10 HFF samples. Lactotransferrin was uniquely included in Ambekar’s data, and was also successfully detected by western blotting in our study. This result not only testified the good quality of Ambekar’s data, but also facilitated to integrate the data from different MS platform in the future. Interestingly, more than 60% of combined HFF proteins from our data and Ambekar’s data were found in the reported human plasma data [29]. HFF was a complex mixture, and the content of HFF mainly originates from the transfer of blood plasma constituents via theca capillaries, and the secretion of granulosa and thecal cells [5]. From the above contrast, we considered the transfer of plasma proteins was the major source of HFF, and the alternative permeability of theca capillaries would change the HFF compositions which inevitably impaired the oocyte quality, and even caused unsuccessful IVF outcome.

Bioinformatics analysis showed that 5% HFF proteins were involved in lipid metabolism and transport process. It has been reported that ageing could decrease apolipoprotein A1 and apolipoprotein CII, while increase apolipoprotein E, which were associated with the decline in production of mature oocytes and the decline in fertility potential [35]. Preconception folic acid supplementation upregulated apolipoprotein A-I and apolipoprotein C-I of the HDL pathway in human follicular fluid, which increased embryo quality and IVF/ICSI treatment outcome [30]. In our HFF data, apolipoprotein A-I, apolipoprotein A-II, apolipoprotein A-IV, apolipoprotein C-I, apolipoprotein C-II, apolipoprotein C-III, apolipoprotein D, apolipoprotein E, apolipoprotein F, and apolipoprotein M were all found, which indicated that those apolipoproteins were related to cholesterol homeostasis and steroidogenesis and played important roles in the maintenance of oocyte maturation microenvironment.

Pathway analysis showed that complement and coagulation cascades were the most prominent pathways (P_Value = 5.8E-52). Complement cascade promoted coagulation through the inhibition of fibrinolysis, and coagulation cascade in return amplified complement activation. Complement cross_talked with coagulation in a reciprocal way [36]. For example, plasmin, thrombin, elastase and plasma kallikrein could activate C3 [37]. Coagulation activation factor XII could cleave C1 to activate the classical complement pathway [38]. And thrombin could also directly cleave C5 to generate active C5a [39]. Among our HFF proteins, components (F12, KLKB1, PLG, KNG1, F9, F10, SERPINC1, SERPIND1, SERPINA5, F2, PROS1, PROC, SERPINA1, SERPINF2, A2M, CPB2, and FGA) of extrinsic pathway and intrinsic pathway in coagulation cascade and those (FH, FI, FB, C3, C1qrs, SERPING1, C2, C4, C4BP, C5, C6, C7, C8A, C8B, C8G, C9, FGA, FGG, PLG, FGB, F10) of alternative pathway, classical pathway, and lectin pathway in complement cascade were all identified. During follicle development and ovulation, coagulation system in HFF contributed to HFF liquefaction, fibrinolysis and the breakdown of follicle wall [40, 41]. Follicle development had been hypothesized as the controlled inflammatory processes in 1994 [42], and inappropriate complement activation was linked to abortion [43]. Inhibition of complement activation improved angiogenesis failure and rescued pregnancies [44]. The paired comparison of HFF with plasma showed C3, C4, C4a, and C9 as well as complement factor H and clusterin might contribute to the inhibition of complement cascade activity for women undergoing controlled ovarian stimulation for IVF [45]. However there were still debates on the role of complement cascade in IVF. Physiologic complement activation protected the host against infection in normal pregnancy [46]. In comparison with those non-fertilized oocytes, C3 was more abundant in HFF from fertilized oocytes [47]. In the course of IVF treatment, the functions of complement and coagulation cascade were very complicated during ovarian hyperstimulation. More works were still deserved in both mechanism research and clinical practice.

Based on the analysis of STRING, we discovered a profound HFF protein-protein interaction networks. 151 of 219 HFF proteins participated in the network with 738 paired relationships. Basement membrane-specific HSPG was found as a node, which was also a potential biomarker for oocyte maturation in HFF. HSPG was widely distributed on the surface of animal cells, and especially strongly expressed in granulosa cells. HSPG played a critical role in controlling inflammation control through binding and activating antithrombin III during folliculogenesis [48]. Women with PCOS showed HSPG defect in follicular development [49], and on the contrary, HSPG was up-regulated in the fertilized-oocyte HFF [32]. In the network, HSPG interacted with 20 of 219 HFF proteins, and constructed 105 paired relationships. We deduced that the loss of HSPG might affect the function of the whole network or more complicated interaction maps, which might cause subsequent failures of oocyte maturation, fertilization, and IVF treatment.

Conclusions

HFF had a natural advantage for the noninvasive prediction of oocyte quality and IVF treatment outcome. The present study would provide a new complementary dataset for better understanding of oocyte maturation, and also delineate a new networks and pathways involved into the folliculogenesis. Furthermore, those novel findings would facilitate to testify the potential biomarkers associated with oocyte quality and IVF outcome. In the future, international laboratory collaboration should be established to standardize and optimize experimental design, patient selection, HFF handling, analysis methods, data standard, and clinical verification, which will greatly promote basic research of reproductive medicine, and ultimately accelerate the clinical transformation.

Abbreviations

- 2D–GE:

-

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

- A2M:

-

Alpha-2-macroglobulin

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- C1qrs:

-

Complement C1q A chain

- C2:

-

Complement C2

- C3:

-

Complement C3

- C4:

-

Complement C4

- C4BP:

-

C4b-binding protein alpha chain

- C5:

-

Complement C5

- C6:

-

Complement C6

- C7:

-

Complement C7

- C8A:

-

Complement component C8 alpha chain

- C8B:

-

Complement component C8 beta chain

- C8G:

-

Complement component C8 gamma chain

- C9:

-

Complement C9

- CE:

-

Capillary electrophoresis

- COH:

-

Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation

- CPB2:

-

Carboxypeptidase B2

- DAVID:

-

The database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery

- F10:

-

Coagulation factor X

- F12:

-

Coagulation factor XII

- F2:

-

Prothrombin

- F9:

-

Coagulation factor IX

- FB:

-

Complement factor B

- FDR:

-

False Discovery Rate

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- FGA:

-

Fibrinogen alpha chain

- FGB:

-

Fibrinogen beta chain

- FGG:

-

Fibrinogen gamma chain

- FH:

-

Complement factor H

- FI:

-

Complement factor I

- HCG:

-

Human chorionic gonadotrophin

- HFF:

-

Human follicular fluid

- HSPG:

-

Heparan sulfate proteoglycan core protein

- IEF:

-

Isoelectric focusing

- IVF:

-

In vitro fertilization

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- KLKB1:

-

Plasma kallikrein

- KNG1:

-

Kininogen-1

- MALDI TOF/TOF:

-

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight tandem

- PANTHER:

-

Protein analysis through evolutionary relationships

- PCOS:

-

Polycystic ovary syndrome

- PLG:

-

Plasminogen

- PROC:

-

Vitamin K-dependent protein C

- PROS1:

-

Vitamin K-dependent protein S

- RP-HPLC:

-

Reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography

- SCX:

-

Strong cation exchange

- SDS-PAGE:

-

One dimensional sodium dodecyl polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SELDI-TOF-MS:

-

surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry

- SERPINA1:

-

Alpha-1-antitrypsin

- SERPINA5:

-

Plasma serine protease inhibitor

- SERPINC1:

-

Antithrombin-III

- SERPIND1:

-

Heparin cofactor 2

- SERPINF2:

-

Alpha-2-antiplasmin

- SERPING1:

-

Plasma protease C1 inhibitor

- STRING:

-

search tool for recurring instances of neighbouring genes

- WCX:

-

weak cation-exchange

- WGOC:

-

Working Group on Obesity in China

References

Steptoe PC, Edwards RG. Birth after the reimplantation of a human embryo. Lancet. 1978;2:366.

Wang HB. Embryo implantation: progress and challenge. Chinese Bulletin of Life Sciences. 2017;29:31–42.

Kovalevsky G, Patrizio P. High rates of embryo wastage with use of assisted reproductive technology: a look at the trends between 1995 and 2001 in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:325–30.

Van Loendersloot LL, van Wely M, Limpens J, Bossuyt PMM, Repping S, der van Veen F. Predictive factors in vitro fertilization (IVF): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;6:577–89.

Fortune JE. Ovarian follicular growth and development in mammals. Biol Reprod. 1994;50:225–32.

Zamah AM, Hassis ME, Albertolle ME, Williams KE. Proteomic analysis of human follicular fluid from fertile women. Clin Proteomics. 2015;3(5):1–12.

Guo N, Liu P, Ding J, Zheng SJ, Yuan BF, Feng YQ. Stable isotope labeling - Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry for quantitative analysis of androgenic and progestagenic steroids. Anal Chim Acta. 2016;905:106–14.

Xia L, Zhao X, Sun Y, Hong Y, Gao Y, Hu S. Metabolomic profiling of human follicular fluid from patients with repeated failure of in vitro fertilization using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7220–9.

Edwards RG. Follicular fluid. J Reprod Fertil. 1974;37:189–219.

Wu YT, Wang TT, Chen XJ, Zhu XM, Dong MY, Sheng JZ, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-15 in follicle fluid combined with age may differentiate between successful and unsuccessful poor ovarian responders. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012;10(116):1–6.

Benkhalifa M, Madkour A, Louanjli N, Bouamoud N, Saadani B, Kaarouch I, et al. From global proteome profiling to single targeted molecules of follicular fluid and oocyte: contribution to embryo development and IVF outcome. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2015;12:407–23.

Li L, Xing FQ, Chen SL, Sun L, Li H. Proteomics of follicular fluid in mature human follicles and antral follicles: a comparative study with laser desorption/ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2008;28(2):275–8.

Wu YT, Wu Y, Zhang JY, Hou NN, Liu AX, Pan JX, et al. Preliminary proteomic analysis on the alterations in follicular fluid proteins from women undergoing natural cycles or controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32:417–27.

Ambekar AS, Nirujogi RS, Srikanth SM, Chavan S, Kelkar DS, Hinduja I, et al. Proteomic analysis of human follicular fluid: a new perspective towards understanding folliculogenesis. J Proteome. 2013;87:68–77.

Chen F, Spiessens C, D'Hooghe T, Peeraer K, Carpentier S. Follicular fluid biomarkers for human in vitro fertilization outcome: Proof of principle. Proteome Sci. 2016;14(17):1–11.

Zhou BF. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference to risk factors of related diseases in Chinese adult population. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2002;23:5–10.

Zhou B. Coorperative Meta-Analysis Group of Working Group On Obesity In China. Prospective study for cut-off points of body mass indexin Chinese adults Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2002;23:431–4.

Zhou BF. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults-study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci. 2002;15:83–96.

Huang X, Hao C, Shen X, Liu X, Shan Y, Zhang Y, et al. Differences in the transcriptional profiles of human cumulus cells isolated from MI and MII oocytes of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Reproduction. 2013;145:597–608.

Gotham SM, Fryer PJ, Paterson WR. The measurement of insoluble proteins using a modified Bradford assay. Anal Biochem. 1988;173:353–8.

Ding C, Jiang J, Wei J, Liu W, Zhang W, Liu M, et al. A fast workflow for identification and quantification of proteomes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:2370–80.

Sun W, Xing B, Guo L, Liu Z, Mu J, Sun L, et al. Quantitative Proteomics Analysis of Tissue Interstitial Fluid for Identification of Novel Serum Candidate Diagnostic Marker for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2016;24:26499.

Mi H, Muruganujan A, Casagrande JT, Thomas PD. Large-scale gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1551–66.

Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57.

Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D353–61.

Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–52.

Liu X, Wang W, Liu F. New insight into the castrated mouse epididymis based on comparative proteomics. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2015;27:551–6.

Liu J, Zhu P, Wang WT, Li N, Liu X, Shen XF, et al. TAT-peroxiredoxin 2 Fusion Protein Supplementation Improves Sperm Motility and DNA Integrity in Sperm Samples from Asthenozoospermic Men. J Urol. 2016;195:706–12.

Farrah T, Deutsch EW, Omenn GS, Campbell DS, Sun Z, Bletz JA, et al. A high-confidence human plasma proteome reference set with estimated concentrations in PeptideAtlas. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M110.006353.

Lo Turco EG, Cordeiro FB, Lopes PH, Gozzo FC, Pilau EJ, Soler TB, et al. Proteomic analysis of follicular fluid from women with and without endometriosis: new therapeutic targets and biomarkers. Mol Reprod Dev. 2013;80:441–50.

Twigt JM, Bezstarosti K, Demmers J, Lindemans J, Laven JS, Steegers-Theunissen RP. Preconception folic acid use influences the follicle fluid proteome. Eur J Clin Investig. 2015;45:833–41.

Bayasula IA, Kobayashi H, Goto M, Nakahara T, Nakamura T, et al. A proteomic analysis of human follicular fluid: comparison between fertilized oocytes and non-fertilized oocytes in the same patient. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30:1231–8.

Hanrieder J, Zuberovic A, Bergquist J. Surface modified capillary electrophoresis combined with in solution isoelectric focusing and MALDI-TOF/TOF MS: a gel-free multidimensional electrophoresis approach for proteomic profiling--exemplified on human follicular fluid. J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216:3621–8.

Hanrieder J, Nyakas A, Naessén T, Bergquist J. Proteomic analysis of human follicular fluid using an alternative bottom-up approach. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:443–9.

Von Wald T, Monisova Y, Hacker MR, Yoo SW, Penzias AS, Reindollar RR, et al. Age-related variations in follicular apolipoproteins may influence human oocyte maturation and fertility potential. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2354–61.

Levi M, van der Poll T, Büller HR. Bidirectional relation between inflammation and coagulation. Circulation. 2014;109:2698–704.

Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, Lambris JD. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:785–97.

Ghebrehiwet B, Silverberg M, Kaplan AP. Activation of the classical pathway of complement by Hageman factor fragment. J Exp Med. 1981;153:665–76.

Huber-Lang M, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, Rittirsch D, Neff TA, McGuire SR, et al. Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: a new complement activation pathway. Nat Med. 2006;12:682–7.

de Agostini AI, Dong JC, de Vantéry AC, Ramus MA, DentandQuadri I, Thalmann S, et al. Human follicular fluid heparan sulfate contains abundant 3-O-sulfated chains with anticoagulant activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28115–24.

Ebisch IM, Thomas CM, Wetzels AM, Willemsen WN, Sweep FC, Steegers-Theunissen RP. Review of the role of the plasminogen activator system and vascular endothelial growth factor in subfertility. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:2340–50.

Espey LL. Current status of the hypothesis that mammalian ovulation is comparable to an inflammatory reaction. Biol Reprod. 1994;50:233–8.

Girardi G, Salmon JB. The role of complement in pregnancy and fetal loss. Autoimmunity. 2003;36:19–26.

Girardi G. Complement inhibition keeps mothers calm and avoids fetal rejection. Immunol Investig. 2008;37:645–59.

Jarkovska K, Martinkova J, Liskova L, Halada P, Moos J, Rezabek K, et al. Proteome mining of human follicular fluid reveals a crucial role of complement cascade and key biological pathways in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:1289–301.

Richani K, Soto E, Romero R, Espinoza J, Chaiworapongsa T, Nien JK, et al. Normal pregnancy is characterized by systemic activation of the complement system. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;17:239–45.

Gonzales J, Lesourd S, van Dreden P, Richard P, Lefebvre G, Brouzes DV. Protein composition of follicular fluid and oocyte cleavage occurrence in in vitro fertilization (IVF). J Assist Reprod Genet. 1992;9:211–6.

de Agostini A. An unexpected role for anticoagulant heparan sulfate proteoglycans in reproduction. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136:583–90.

Ambekar AS, Kelkar DS, Pinto SM, Sharma R, Hinduja I, Zaveri K, et al. Proteomics of follicular fluid from women with polycystic ovary syndrome suggests molecular defects in follicular development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:744–53.

Acknowledgements

We thank Guo Lihai PhD (Shanghai Asia Pacific Application Support Center, Applied Biosystems, China) for the usage training of LC MALDI TOF/TOF 5800 mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, USA).

Funding

The current study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81300533 81501313 and 81571490), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China (grant nos. ZR2014HQ068 and ZR2015HQ031) and Yantai Science and Technology Program (grant no. 2015WS019, 2015WS024 and 2016WS001).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available fromthe corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XS, XL, FL conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and reviewed the final manuscript for submission. PZ participated in the design of study, carried out the studies and drafted the manuscript. YZ, JW, YW, WW participated in the design of study, carried out the studies and helped to draft the manuscript. XL, FL, PZ performed the proteomic analysis. JL, NL carries out the bioinformatics analysis. XS participated in the study design and performed the HFF collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing BaoDao Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, and written informed consents were obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

The information of antibodies and secondaries for Western blotting. (XLSX 10 kb)

Additional file 2:

The overlap of known data and novel findings. (JPEG 1344 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, X., Liu, X., Zhu, P. et al. Proteomic analysis of human follicular fluid associated with successful in vitro fertilization. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 15, 58 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-017-0277-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-017-0277-y