Abstract

Background

Solitary fibrous tumours (SFT) are neoplasms of mesenchymal origin that predominantly arise from the pleura. SFT of the liver (SFTL) are a rare occurrence with little number of cases reported in English literature. Malignant cases of hepatic SFT are an even rarer occurrence. For this reason, the prognostic evaluation of SFTLs is unknown and difficult to measure.

Methods

A search on English literature on “Solitary Fibrous Tumour of the Liver” was conducted on common search engines (PubMed, Google). All published articles, case reports and literature reviews and their reference lists were reviewed.

Case report

This paper presents a 61-year-old male who was referred to a tertiary hospital in April 2010 with marked hepatomegaly. USS, CT and MRI scans were suggestive of a neoplasm, and the patient underwent a subsegmental IVb resection in June 2010. The specimen demonstrated histological and immunohistochemical features of malignant SFTL with clear resection margins. The patient was followed up regularly for 3 years with imaging and no suggestion of recurrence. Six years after the initial surgery, the patient represented with worsening right upper quadrant pain and dyspnoea secondary to extensive tumour recurrence adjacent to the resection site and metastatic deposits in the pleura. The patient was managed symptomatically and discharged for community follow-up after palliative involvement.

Conclusions

SFTL are rare with only 84 cases reported in the English Literature including the present case. The average age of patients is 57.1 and occurs in females more than males (1.4:1). Most SFTLs follow a benign course, however, 17.9% of cases displayed malignant histological features. Only three cases including the current case are reported to have both local recurrence and metastasis. Surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment and appears to be curative of most cases. The rarity of this tumour makes it difficult to evaluate its prognosis and natural course.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Solitary fibrous tumours (SFT) are soft tissue neoplasms of mesenchymal origin first described in 1931 by Klemperer and Rabin [1]. They are typically found in the pleura but are ubiquitously distributed and have been reported to originate from a number of extrapleural sites. Solitary fibrous tumours of the liver (SFTL) are rare, with only 84 reported cases in the English literature (PubMed + Google + publication references) including the present case. Most SFTLs are benign but there have been a handful of reports on malignant cases, some of which have had local recurrences and metastatic spread.

Diagnosis is typically made with histopathological findings and immunohistochemical examination of resected samples. Preoperative investigation of SFTLs can be difficult with non-specific radiological features. Biopsy of radiological liver lesions remains controversial due to the risk of inconclusive results [2, 3] or seeding of the biopsy tract [4]. Given the malignant potential of these tumours, surgical resection is the preferred method of treatment if possible.

This report is only the third described case of its kind in the English literature, a malignant SFTL with extensive local recurrence and metastatic spread 6 years following clear resection margins.

Main text

Case presentation

A 61-year-old male was referred to the emergency department by his general practitioner in April 2010 for investigation of loose bowel motions and an episode of black stool. The patient had a history of insulin-dependent type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease with two previous ischaemic events, obstructive sleep apnoea, depression, schizophrenia and a previous incisional hernia repair.

On examination, he was morbidly obese (BMI 45) and was noted to have marked hepatomegaly. This was not associated with any recent weight loss, haematemesis, jaundice or abdominal pain. The patient denied previous blood transfusions, usage of intravenous drugs and did not drink alcohol. A faecal occult blood test was negative, and the patient’s last colonoscopy 2 years prior was unremarkable.

He was referred to our tertiary centre for further management after an ultrasound scan (USS) displayed an ovoid mass of mixed echogenicity arising from the liver, measuring 12 × 9 cm. A computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed a malignant appearing, pedunculated lesion attached to segment IV (Fig. 1). A subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed that on T2 weighted imaging (WI), the lesion was isointense to the liver peripherally with central branching hyperintensities (Fig. 2a) which corresponded to the hypointensities seen on T1WI (Fig. 2b). Enhancement of the lesion was noted in arterial phase (Fig. 3a), during portal venous phase (Fig. 3b) and at 2 min (Fig. 3c), with some central areas of non-enhancement. The lesion becomes slightly hypointense on delayed images at 10 (Fig. 3d) and 20 min compared to the surrounding liver.

Laboratory investigations revealed a mildly elevated gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase of 137 IU/L (normal 5–50 IU/L). Hepatitis screen, alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen and cancer antigen 19–9 were all unremarkable.

The patient underwent a subsegmental resection of the 15 cm segment IVb mass in June 2010. There was severe hepatic steatosis, but no cirrhosis. The patient was discharged postoperative day seven without complications.

Pathology of the resection specimen confirmed SFTL. The specimen displayed a pale tan nodular appearance with a firm and rubbery cut surface. Histological examination revealed fascicles of spindle cells in storiform arrangement with a pushing margin. There was evidence of extracellular collagen deposition, areas of myxoid stroma and branching vessels with hyalinisation. The specimen displayed a high mitotic rate of up to 9 per 10 high-power fields (HPF) with no necrotic or haemorrhagic features. Immunohistochemistry showed positive staining for CD34, CD99 and BCL-2. The tumour was negative for c-Kit, CD31, SMA, desmin, cytokeratins (AE1/AE3, MNF116 and Cam 5.2), EMA and S100. The margins were clear. The non-neoplastic remainder of the liver displayed pericellular fibrosis indicative of steatohepatitis.

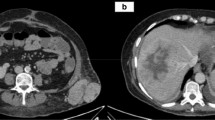

The patient was followed-up regularly every 4 to 6 months with CT scans by the local general practitioner who liaised with the consultant surgeon. There were two episodes of re-admissions for further investigation of recurrent right upper quadrant pain between 2011 and 2013. Multiple MRI scans performed during this period revealed expected postsurgical changes with no tumour recurrence. However, in May 2016, the patient presented to his local emergency department with progressively worsening right upper quadrant pain and increasing dyspnoea with an oxygen demand. CT of his chest, abdomen and pelvis revealed extensive tumour recurrence adjacent to the previous resection site (Fig. 4). In addition, there was a clinically significant right-sided pleural effusion and a pleural mass at the right lung base measuring 3.8 cm (Fig. 5).

Pleurocentesis was performed, draining 1400 ml of serosanguineous fluid. Cytology was negative for malignant cells. The case was discussed extensively in a multi-disciplinary setting, and it was decided given the patient’s two sites of disease and significant perioperative risk that he was not a candidate for radical reoperation. There were also no suitable chemo- or radiotherapeutic therapies available. The patient was subsequently referred to the palliative team for management of his symptoms and discharged back to the community. He was still alive 1 month after discharge.

Discussion

SFTs are fibroblastic neoplasms first described in 1931 [1] that are of mesenchymal origin and typically arise from the pleura. Initially thought to be of mesothelial origin, they have been historically referred to as benign mesothelioma, localised fibrous mesothelioma and pleural fibromas [5]. Their extrapleural involvement and ubiquitous nature have been well described over the last century with publications documenting primary cases arising from the respiratory tract [6], orbit [7], thyroid [8], adrenal gland [9], spinal cord [10], meninges [11], breasts [12], peritoneum [13], pancreas [14] and soft tissues [15].

SFTs involving the liver are exceptionally rare with only 84 cases reported in the English literature since 1958 (Table 1). The average age of patients is 57.1 (range 16–87) and appears to occur in females more than males (1.4:1). Most SFTLs follow a benign course, however, 17.9% (n = 15) of cases displayed malignant histological features.

The clinical presentation of SFTL is generally non-specific, ranging from weight loss and fatigue to upper abdominal fullness [16] or discomfort due to the tendency of these tumours to be quite large. In many cases, SFTLs are found incidentally during routine examination [17–22] or on routine imaging while investigating other pathologies [2, 23–25]. Patients may also present with symptoms secondary to compression of visceral or neurovascular structures adjacent to the mass such as dyspepsia [26], postprandial pain/nausea/vomiting [22, 27–29] or jaundice [30]. There is no specific laboratory or tumour marker for SFTL, and serum investigations are generally non-informative. A small percentage of patients (13.1%) however, present with paraneoplastic syndromes such as non-islet cell tumour hypoglycaemia [31] associated with extrinsic production of high-molecular weight insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II) which spontaneously resolves after resection of the mass [17, 19, 24, 30–37]. There does not appear to be an association between hypoglycaemic presentations and malignant cases (n = 1). These IGF-II associated SFTs have also been documented in cases involving the pleura and so are not limited to SFTLs [38].

Preoperative diagnosis is difficult due to non-specific radiological findings. Sonography often reveals a heterogeneous mass which may be either or both hypo- and hyperechogenic with or without calcifications. A contrast-enhanced CT characteristically shows early arterial enhancement with delayed venous washout [3, 22]. Findings on MRI are similar to that of CT scans. In T1WI, the SFTL demonstrates a heterogeneous mass with hypointense signals compared to the normal hepatic parenchyma which is thought to reflect the high content of collagenous tissue [39, 40]. A heterogeneous mass that may be both hypo- and hyperintense is observed in T2WI with some areas described as almost isointense to cerebrospinal fluid [18, 41]. On images post-gadolinium-based contrast injection, SFTLs display progressive heterogeneous enhancement starting in the arterial phase corresponding to the hypervascular areas and persisting into the venous and delayed phases, likely due to the collagen-rich interstitium [42]. There does not appear to be any features on either USS, CT or MRI that differentiates between benign or malignant disease without a tissue diagnosis.

Percutaneous biopsy for tissue diagnosis prior to resection is a much debated topic but is a well-documented approach in the lead up to the resection of SFTLs [3, 16, 18, 27, 28, 31, 40, 43–47]. Given the many risks it poses—including seeding the tumour via the needle tract [4, 48], pain, intrahepatic or subcapsular haematoma and bile leaks [4]—it is doubtful whether preoperative biopsy would change management if the lesion is able to be safely resected [24]. Fuksbrumer et al. [18] describes a case which showed histological changes suggesting low-grade malignant transformation which was not discovered in the initial biopsy while Korkolis et al. [3] reports a case of SFTL whose initial biopsy was indicative of hepatocellular carcinoma. A third report by Chen et al. [2] presents a case in which a biopsy suggested metastatic pancreatic or upper gastrointestinal tract lesion in a patient with a history of colorectal adenocarcinoma prior to resection. Postoperative histological examination indicated SFTL and disproved the preoperative diagnosis.

Diagnosis is limited to histopathological and immunohistochemical investigations. Macroscopic examination of SFTLs appears to be relatively consistent amongst all cases in this literature review. SFTLs range in size, measuring from 0.5 [17] to 35 cm [34]. They tend to be grey-white or tan-yellow in colour and are well-circumscribed, nodular and encapsulated by a smooth glistening capsule, often continuous with the Glisson’s capsule [27, 47, 49]. On the cut surfaces, they are well documented to be firm and difficult to cut with a whorled bulging appearance interspersed with central areas of scarring and radiating bands of fibrous tissue. Some SFTLs may also display features of myxoid degeneration [3, 22, 26, 40, 50], necrosis [20, 27, 28, 35, 42, 51, 52], haemorrhage [20, 51] or cystic cavitation [2, 24, 29, 34, 35, 40, 42, 53].

Microscopically, they are composed of ovoid spindle-shaped cells with little cytoplasm within a characteristic storiform or haphazardly ‘pattern-less pattern’ architecture. These cells are distributed between alternating hypo- and hypercellular areas separated from each other by thick bands of keloid-like collagen bundles and branching of staghorn vessels resembling a haemangiopericytoma-like pattern. Myxoid changes were also commonly observed [17, 26]. Mitoses are rare and generally limited to malignant cases, as is necrosis and cytological atypia. Most cases displayed mitoses <4/10HPF. In 2002, the World Health Organization (WHO) revised their classification of tumours and recognised SFTs as a fibroblastic/myofibroblastic tumour and identified it as a separate entity to haemangiopericytomas. Features identified by WHO to be associated with malignancy include hypercellularity, cytologic atypia, tumour necrosis, infiltrative margins and high mitotic activity (≥4/10 HPF) [54].

There are no specific immunohistochemical profiles for SFTL, however, there are a few markers which are characteristic such as CD34 which has shown strong reactivity in all documented cases as well as CD99, BCL-2 and Vimentin which do not appear as sensitive. Durak et al. [55] reports an interesting case in which there was a strong positivity for CD34 and CD99 but similarly for smooth muscle actin and focal weak positivity for oestrogen and progesterone receptors in the spindle cells which has not been documented before. Few cases report immunoreactivity to desmin [3, 51] (n = 2) and actin [51, 55] (n = 2). SFTLs are otherwise typically negative for c-Kit (CD117), CD31, cytokeratins, EMA, factor VIII, epithelial membrane antigen and S100.

On literature review, there appears to be sixteen cases documenting malignant SFTLs (Table 2), local recurrence or distant metastases. 17.9% (n = 15) of patients were diagnosed with malignant SFTL based on the histology reports. The average age of these patients was 59.6 years with almost equal distribution between males and females (7:8). Of these cases, 26.7% (n = 4) were noted to have local recurrence (9 months–6 years) and 53% (n = 8) to have distant metastasis (1 month–6 years). This compared similarly to intrapleural SFTs with recurrence rates of 20–67% in malignant tumours [35].

Only three cases [35, 51] including the current case are reported to have both local recurrence and metastasis but no significant features to foresee this could be identified in this data. All three were male and their average age was 61.7 years. The size of tumours ranged from 11 to 27 cm and two of the three cases had high rates of mitoses (>9/10 HPF). It is interesting to note that Du et al. [56] reports a case on a 55-year-old female with non-malignant SFTL who represented 5 years after initial surgery with local recurrence and associated hypoglycaemia which resolved spontaneously after resection. The tumour did not display any marked variances when compared to other non-malignant SFTLs.

Surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment for SFTLs and appears to be the cure for most cases where histopathology returns showing a benign lesion with a clear resection margin of >1 cm. There is very little literature on the use of radio- and chemotherapy, and its efficacy in the long-term is unknown given the scant experience with these approaches. El-Khouli et al. [43] describes a case of SFTL treated with three sessions of transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) for an inoperable lesion. They describe a favourable outcome on the basis of increased intratumoral necrosis, reduced tumoural enhancement and stabilisation of tumour size based on consecutive MRI scans. Beyer et al. [45] describes a case where the SFTL was initially thought to be a desmoid tumour, and the patient was managed with hormone replacement therapy before imatinib was trialled with no effect. The patient eventually underwent surgical resection with no malignant features evident. Feng et al. [20] presents a case series with one patient undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy (mitomycin) due to extensive tumour infiltration of multiple vascular structures and another patient who was trialled on percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy and percutaneous ethanol injection for local recurrence without success as new lesions were found 6 months later on follow-up. Maccio et al. [46] reports a case series where two patients underwent chemotherapy for SFTL with metastatic spread to the lungs without success as both patients died within 5 months.

Prognosis for SFTLs is unknown and difficult to measure due to the little experience and understanding of the biological nature of the disease. The rarity of this tumour makes it hard to gather enough cases for a study on alternative treatment options, and the absence of long-term follow-up also hinders on the evaluation of patient outcome over long-periods for both benign and malignant cases. The use of adjuvant radio- and/or chemotherapy as well as TACE is scarcely reported and so its efficacy cannot be commented on. It would be valuable to review these patients several years down the track to see how their disease has progressed.

Conclusion

SFTL is a rare neoplasm that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with vague abdominal symptoms secondary to compression of adjacent structures due to a large hepatic mass. Radiological findings are often non-specific and are unable to differentiate between a benign or malignant mass and percutaneous biopsies are not recommended if the tumour is considered resectable. Complete surgical resection is, thus, the recommended treatment of choice and curative in most cases as the risk for malignant transformation and metastatic spread is not unheard of. Careful long-term follow-up is suggested as prognosis is uncertain for these lesions. This case provides yet another example of the malignant potential of SFTLs to recur locally and metastasise to distant locations.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- HPF:

-

High-power fields

- IGF:

-

Insulin-like growth factor

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SFT:

-

Solitary fibrous tumours

- SFTL:

-

Solitary fibrous tumours of the liver

- TACE:

-

Transarterial chemoembolization

- USS:

-

Ultrasound scan

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WI:

-

Weighted imaging.

References

Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura. A report of five cases. Am J Ind Med. 1992;22(1):1–31.

Chen JJ, Ong SL, Richards C, et al. Inaccuracy of fine-needle biopsy in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumour of the liver. Asian J Surg. 2008;31(4):195–8.

Korkolis DP, Apostolaki K, Aggeli C, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver expressing CD34 and vimentin: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(40):6261–4.

Cresswell AB, Welsh FKS, Rees M. A diagnostic paradigm for resectable liver lesions: to biopsy or not to biopsy? HPB. 2009;11:533–40.

Janssen JP, Wagenaar S, Van Den Bosch J, et al. Benign localised mesothelioma of the pleura. Histopathology. 1985;9(3):309–13.

Papadakis I, Koudounarakis E, Haniotis V, Karatzanis A, Velegrakis G. Atypical solitary fibrous tumor of the nose and maxillary sinus. Head Neck. 2013;35(3):77–9.

Meyer N, Matos BHF, Oliveira LR, Mendonca AT. Report of a case of solitary fibrous tumour of the orbit. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;17:225–7.

Santeusanio G, Schiaroli S, Ortenzi A, Mule A, Peroone G, Fadda G. Solitary fibrous tumour of thyroid: report of two cases with immunohistochemical features and literature review. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2:231–5.

Ho YH, Yap WM, Chuah KL. Solitary fibrous tumor of the adrenal gland with unusual immunophenotype. A potential diagnostic problem and a brief review of endocrine organ solitary fibrous tumor. Endocr Pathol. 2010;21:125–9.

Mordani JP, Haq IU, Singh J. Solitary fibrous tumour of the spinal cord. Neuroradiology. 2000;42:679–81.

Benoi M, Janzer RB, Regli L. Bifrontal solitary fibrous tumor of the meninges. Surg Neurol Int. 2010;1:35.

Rhee SJ, Ryu JK, Han SA, Won KY. Solitar fibrous tumor of the breast: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Ultrasonics. 2016;43:125–8.

Fukunaga M, Naganuma H, Ushigome S, Endo Y, Ishikawa E. Malignant solitary fibrous tumour of the peritoneum. Histopathology. 1996;28:463–6.

Tesfom MF, Caldwell C, Hanasoge R, Bramhall SR. Lungs and subcutaneous metastases from a solitary fibrous tumour of the pancreas. J Surg Case Rep. 2015;11:1–3.

Profyiris C, Soilleux E, Corkill R, Birch J. Solitary fibrous tumour of the face: a rare case report. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:13–5.

Bejarano PA, Blanco R, Hanto DW. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. A case report, river of the literature and differential diagnosis of spindle cell lesions of the liver. Int J Surg Pathol. 1998;6(2):93–100.

Moran CA, Ishak KG, Goodman ZD. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of nine cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 1998;2(1):19–24.

Fuksbrumer MS, Klaimstra D, Panicek DM. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(6):1683–7.

Vennarecci G, Ettorre GM, Giovannelli L, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:341–4.

Feng LH, Dong H, Zhu YY, Cong WM. An update on primary hepatic solitary fibrous tumor: an examination of the clinical and pathological features of four case studies and a literature review. Pathol Res Pract. 2015;211:911–7.

Hoshino M, Nakajima S, Futagawa Y, Fujioka S, Okamoto T, Yanaga K. A solitary fibrous tumor originating from the liver surface. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2009;2:320–4.

Ji Y, Fan J, Xu Y, Zhou J, Zeng HY, Tan YS. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5(1):151–3.

Kueht M, Masand P, Rana A, Cotton R, Goss J. Concurrent hepatic hemangioma and solitary fibrous tumor: diagnosis and management. J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7:1–4.

Silvanto A, Karanjia ND, Bagwan IN. Primary hepatic solitary fibrous tumor with histologically benign and malignant areas. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2015;14(6):665–8.

Haddad A, Karras R, Fraiman M, Mackey R. Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Liver. Am Surg. 2010;76(7):78–9.

Patra S, Vij M, Venugopal K, Rela M. Hepatic solitary fibrous umor: a report of a rare case. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55(2):236–8.

Guglielmi A, Frameglia M, Iuzzolino P, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver with CD 34 positivity and hypoglycaemia. J Hep Bil Pancr Surg. 1998;5:212–6.

Terkivatan T, Kliffen M, de Wilt JHW, Geel ANV, Eggermon AMM, Verhoef C. Giant solitary fibrous tumour of the liver. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;21(4):81.

Kim H, Damjanov I. Localised fibrous mesothelioma of the liver. Report of a giant tumour studied by light and electron microscopy. Cancer. 1983;52(9):1662–5.

Yilmaz S, Kirimlioglu V, Ertas E, et al. Giant solitary fibrous tumor of the liver with metastasis to the skeletal system successfully treated with trisegmentectomy. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45(1):168–74.

Fama F, Bouc YL, Barrande G, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the liver with IGF-II-related hypoglycaemia. A case report. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:611–6.

Chithriki M, Jaibaji M, Vandermolen R. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver with presening symptoms of hypoglycemic coma. Am Surg. 2004;70(4):291–3.

Radunz S, Baba HA, Sotiropoulos GC. Large tumor of the liver and hypoglycemic shock in an 85-year-old patient. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:10–1.

Moser T, Nogueira TS, Neuville A, et al. Delayed enhancement pattern in a localised fibrous tumor of the liver. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1578–80.

Chan G, Horton PJ, Thyssen S, et al. Malignant transformation of a solitary fibrous tumor of the liver and intractable hypoglycaemia. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:595–9.

Nevius DB, Friedman NB. Mesotheliomas and extraovarian thecomas with hypoglycaemic and nephritic syndromes. Cancer. 1959;12(6):1263–9.

Lin YT, Lo GH, Lai KH, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 2001;64(5):305–9.

Tapias LF, Lanuti M. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: review of literature with up-to-date observations. Lung Cancer Manag. 2015;4(4):169–79.

Obuz F, Secil M, Sagol O, Karademir S, Topalak O. Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging findings of solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Tumori. 2007;93:100–2.

Bejarano-Gonzalez N, Garcia-Borobia FJ, Romaguera-Monzonis A, et al. Soliary fibrous tumor of the liver. Case report and review fo the literature. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107(10):633–9.

Changku J, Shaohua S, Zhicheng Z, Shushen Z. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: retrospecive study of reported cases. Cancer Invest. 2006;24:132–5.

Soussan M, Felden A, Cyrta J, Morere JF, Douard R, Wind P. Case 198: solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Radiology. 2013;269(1):304–8.

El-Khouli RH, Geschwind JFH, Bluemke DA, Kamel IR. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: magnetic resonance imaging evaluation and treatment with transarterial chemoembolisation. J Compt Assist Tomogr. 2008;32(5):769–71.

Nath DS, Rutzick AD, Sielaff TD. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. AJR. 2006;187:187–90.

Beyer L, Delpero JR, Chetaille B, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor in the round ligament of the liver: a fortunate intraoperative discovery. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5:187–94.

Maccio L, Bonetti LR, Siopis E, Palmiere C. Malignant metastasizing solitary fibrous tumors of the liver: a report of three cases. Pol J Pathol. 2015;66(1):72–6.

Kottke-Marchant K, Hart WR, Broughan T. Localized fibrous tumor (localized fibrous mesothelioma) of the liver. Cancer. 1989;64:1096–102.

Chang S, Kim SH, Lim HK, et al. Needle tract implantation after percutaneous interventional procedures in hepatocellular carcinomas: lessons learned from a 10-year experience. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9:268–74.

Barnoud R, Arvieux C, Pasquier D, Pasquier B, Letoublon C. Solitary fibrous tumour of the liver with CD34 expression. Histopathology. 1996;28:551–4.

Novais P, Robles-Medranda C, Pannain VL, Barbosa D, Biccas B, Fogaca H. Solitary fibrous liver tumor: is surgical approach the best option? J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19(1):81–4.

Brochard C, Michalak S, Aube C, et al. A not so solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:716–20.

Peng L, Liu Y, Ai YB, Liu Z, He Y, Liu Q. Skull base metastases from a malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. A case report and literature review. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:127.

Morris R, McIntosh D, Helling T, Martin Jr JN. Solid fibrous tumor of the liver: a case in pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(6):866–8.

Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002.

Durak MG, Sagol O, Tuna B, et al. Cystic solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: a case report. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2013;29(3):217–20.

Du EHY, Walshe TM, Buckley AR. Recurring rare liver tumor presenting with hypoglycemia. Gastroenteroloy. 2015;148:11–3.

Edmondson HA. Tumors of he liver and intrahepatic bile ducts. In: Atlas of Tumor Pathology, Fascicle 25. Washington: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1958.

Ishak KG. Mesenchymal tumors of the liver. In: Okusa K, Peters RL, editors. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1976. p. 247–307.

Kasano Y, Tanimura H, Tabuse K, Nagai Y, Mori K, Minami K. Giant fibrous mesothelioma of the liver. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86(3):379–80.

Levine TS, Rose DS. Solitary fibrous tumour of the liver. Histopathology. 1997;30(4):396–7.

Lecesne R, Drouillard J, Bail BL, Saric J, Balabaud C, Laurent F. Localised fibrous tumor of the liver: imaging findings. Eur Radiol. 1998;8(1):36–8.

Gold JS, Antonescu CR, Hajdu C, et al. Clinicopathologic correlates of solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer. 2002;94(4):1057–68.

Neeff H, Obermaier R, Technau-Ihling K, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the liver: case report and review of the literature. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2004;389(4):293–8.

Lehmann C, Mourra N, Tubiana JM, Arrivé L. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. J Radiol. 2006;87:139–42.

Perini MV, Herman P, D’Albuquerque LAC, Saad WA. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: report of a rare case and review of the literature. Int J Surg. 2008;6(5):396–9.

Weitz J, Klimstra DS, Cymes K, et al. Management of primary liver sarcomas. Cancer. 2007;109(7):1391–6.

Kandpal H, Sharma R, Gupta SD, Kumar A. Solitary fibrous tumour of the liver: a rare imaging diagnosis using MRI and diffusion-weighted imaging. Br J Radiol. 2008;81(972):e282–6.

Park HS, Kim YK, Cho BK, Moon WS. Pedunculated hepatic mass. Liver Int. 2011;31(4):541.

Sun K, Lu JJ, Teng XD, Ying LX, Wei JF. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:37.

Belga S, Ferreira S, Lemos MM. A rare tumor of the liver with a sudden presentation. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(3):e14–5.

Liu Q, Liu J, Chen W, Mao S, Guo Y. Primary solitary fibrous tumors of liver: a case report and literature review. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:195.

Jakob M, Schneider M, Hoeller I, Laffer U, Kaderli R. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor involving the liver. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(21):3354–7.

Debs T, Kassir R, Amor IB, Martini F, Iannelli A, Gugenheim J. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1291–4.

Vythianathan M, Jim Y. A rare primary malignant solitary fibrous tumour of the liver. Pathology. 2013;45:86–7.

Song L, Zhang W, Zhang Y. 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging of malignant hepatic solitary fibrous tumor. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39(7):662–4.

Teixeira F, de Freitas Perina AL, de Oliveira Mendes G, de Andrade AB, da Costa FPP. Fibrous Solitary Tumour of the Liver. J Gastrointest Canc. 2014;45 suppl 1:216–7.

Beltran MA. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: a review of the current knowledge and report of a new case. J Gastrointest Canc. 2015;46:333–42.

Makino Y, Miyazaki M, Shigekawa M, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver from development to resection. Intern Med. 2015;54(7):765–70.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

NC was involved in the design, literature search, review of literatures and in drafting the manuscript. KS was involved in the manuscript’s conception, supervision and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for release of his medical information and publication of the case report.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval from the Metro South Health Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) was obtained (HREC/16/QPAH/562).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, N., Slater, K. Solitary fibrous tumour of the liver—report on metastasis and local recurrence of a malignant case and review of literature. World J Surg Onc 15, 27 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-017-1102-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-017-1102-y