Abstract

Background

Patient-reported outcomes have been associated with survival in numerous studies across cancer types, including breast cancer. However, the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) and the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (RSCL) have rarely been investigated in this regard in breast cancer.

Methods

Here we describe a post hoc analysis of the prognostic effect of baseline scores of these instruments on survival in a phase III trial of patients with advanced breast cancer who received gemcitabine plus paclitaxel or paclitaxel alone after anthracycline-based adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy. The variables for this analysis were baseline BPI-SF “worst pain” and BPI-SF “pain interference” scores, and four RSCL subscales (each transformed to 0–100). Univariate and multivariate Cox models were used, the latter in the presence of 11 demographic/clinical variables. Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests were used to compare survival for patients by BPI-SF or RSCL scores.

Results

Of 529 randomized patients, 286 provided BPI-SF data and 336 provided RSCL data at baseline. Univariate analyses identified BPI-SF worst pain and pain interference (both hazard ratios [HR], 1.07 for a 1-point increase; both p ≤ 0.0061) and three of four RSCL subscales [activity level, physical distress, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (HR, 0.86–0.91 for 10-point increase all p ≤ 0.0104)], to have significant prognostic effect for survival. BPI-SF worst pain (p = 0.0342) and RSCL activity level (p = 0.0004) were prognostic in the multivariate analysis. Median survival for patients categorized by BPI-SF worst pain score was 23.8 (n = 91), 17.9 (n = 94) and 14.6 (n = 94) months for scores 0, 1–4, and 5–10, respectively (log-rank p = 0.0065). Median survival was 23.8 and 14.6 months for patients (n = 330) with above- and below-median RSCL activity level scores respectively (log-rank p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Pretreatment BPI-SF worst pain and RSCL activity scores provide distinct prognostic information for survival in patients receiving paclitaxel or gemcitabine plus paclitaxel for advanced breast cancer even after controlling for multiple demographic and clinical factors.

Trial registration

Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00006459.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy worldwide and the largest cause of cancer-related death in women [1]. With advancements across screening and treatment modalities over the past 3 decades, evidence from institutional databases and clinical trials [2, 3] suggests that patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) are surviving longer than the median of 18–24 months that has been traditionally reported [4]. However, it unfortunately still remains an incurable disease in nearly all instances, and the goal of treatment is to palliate or prevent symptoms, delay disease progression, and prolong survival [4]. Patients living with advanced disease can experience diminished health-related quality of life (HRQOL) due to cancer- and treatment-related symptoms, such as pain, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, sleep disturbances, arm morbidity, neuropathy, and menopausal symptoms [5, 6].

Self- report from cancer patients provides a unique perspective that addresses aspects of wellbeing, feelings, and functioning, which may not be otherwise captured with standard clinical assessments [7]. Patients who have reported worsening of symptoms and HRQOL have also experienced deterioration in their clinical condition [7, 8]. Research has shown that HRQOL-related information can serve as a useful adjunct to conventional clinical assessments for oncology patients by improving patient-clinician communication and, in particular, helping clinicians understand patient challenges from a psychosocial perspective [7, 9–16]. Understanding all of these factors is increasingly important in oncology in order to optimize the care of patients [17–20].

Patient-reported outcome data obtained from validated instrumentation have demonstrated consistency and reliability in association with clinical outcomes for cancer and non-cancer conditions [21, 22]. Given the increasing potential for such data to be clinically informative [23, 24], patient-reported outcomes and symptoms have emerged as important measures of cancer treatment in clinical trials. Stratifying patients in clinical trials by baseline HRQOL can result in more homogeneous treatment groups and allow for better understanding of study results [25].

Patient-reported outcomes, assessed via a variety of different instruments, have shown independent prognostic value for survival in post hoc analyses of clinical trials [26–29] and in observational studies of MBC patients undergoing cancer treatment [30, 31]. The prognostic value of HRQOL and associated domains has also been demonstrated in an exploratory fashion across other solid-tumor-specific studies, [7, 32–39] as well as in systematic reviews and meta-analyses [7, 25]. A recent analysis of 7417 patients examined the relative value of different HRQOL domains for multiple cancer types using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (QLQ-C30). Results demonstrated that HRQOL parameters of greatest prognostic value differed by cancer type, and the effect size of each parameter varied according to tumor site. For breast cancer as well as other cancer types, at least one domain provided additional prognostic information to that obtained from clinical and sociodemographic variables [23].

The current report is an exploratory, post hoc analysis of clinical and HRQOL outcomes from a phase III trial comparing gemcitabine plus paclitaxel with paclitaxel alone in patients with advanced breast cancer. As previously reported [40], patients receiving doublet therapy experienced significantly improved survival versus paclitaxel alone and were also more likely to have improved HRQOL over time as measured by the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) and Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (RSCL). Here we evaluate the prognostic effect of BPI-SF and RSCL baseline scores on survival. The BPI-SF is used extensively in clinical practice [41] and it has been used across many studies in breast cancer to assess pain. To our knowledge, however, this is the first exploratory report evaluating the prognostic significance of baseline pain and the relationship to survival utilizing this instrument. Other studies in advanced breast cancer to date have utilized the RSCL [42–44] although none have reported the prognostic significance of baseline scores. The current analysis therefore adds to the body of research by evaluating the prognostic effect of baseline scores for pain and other HRQOL domains on survival in advanced breast cancer utilizing the BPI-SF and the RSCL.

Methods

Study design

This was a post hoc analysis of a phase III, multinational, clinical trial evaluating paclitaxel with and without gemcitabine in women with advanced breast cancer who relapsed after adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy with an anthracycline, or non-anthracycline if there was a contraindication (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00006459). As reported by Albain et al. [40], eligible patients were to have had Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) ≥ 70, adequate bone marrow reserve, liver and renal function, normal calcium levels, and an estimated life expectancy of ≥12 weeks at baseline. Prior systemic treatment for metastatic disease was not allowed. Patients were randomly allocated to paclitaxel, with or without concurrent gemcitabine, and treatment cycles continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or patient withdrawal. There were 529 randomized patients from 19 countries. The primary endpoint was overall survival, which was defined as the time from randomization to death from any cause, and surviving patients were censored at the last visit date. Patients completed the BPI-SF and the RSCL within 1 week prior to randomization and at the end of each treatment cycle. Both the questionnaires were completed by patients for whom validated translations were available. The RSCL was included in this study to better understand the impact of treatment on patient’s symptoms and the influence of symptoms on physical and psychological function. The BPI-SF was included to allow a more focused evaluation of pain, which is not specifically evaluated by the RSCL. Efficacy, safety, and patient-reported outcomes results have been previously reported [40, 45, 46]. The study was conducted according to Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice guidelines, and was approved by each participating center’s ethics review board. All patients signed informed consent forms that described the clinical and HRQOL components of the study.

Patient-reported outcome instrumentation

The BPI-SF is a valid and reliable instrument [41], originally developed to assess chronic pain and its impact on HRQOL [47]. This instrument is widely used in clinical practice settings and research to measure the impact of cancer pain [41]. Patients rate their pain and its effects as experienced in the preceding 24 hours. The BPI-SF measures pain intensity (worst, least, average, current), pain relief, and interference of pain (on 7 HRQOL dimensions of general activity, mood, walking, normal work, relations with others, sleep, and enjoyment of life). Scores for the worst pain item as well as pain interference were used in this analysis. Worst pain scores range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain). Pain interference scores range from 0 (no interference) to 10 (complete interference) and were calculated as the mean of the seven pain interference items.

The RSCL is a validated instrument for measuring HRQOL and symptoms in cancer patients [48, 49]. The instrument assesses symptoms and effects of symptoms on anxiety, depression, functional status, and quality of life during the week prior to completing the questionnaire. It has been used previously by patients with advanced breast cancer [44, 50], as well as in numerous other cancer trials [51–55]. Patients answer items for different symptoms via a Likert scale (not at all, a little, quite a bit, very much) comprising four dimensions: physical distress (23 items), psychological distress (7 items), activity level (8 items), and a single item to measure overall HRQOL. For the purposes of this study, the RSCL subscales were each transformed to 0–100, with 100 as the best score.

Statistical analyses

The present post hoc analysis utilized patient-reported outcome scores measured at baseline only. All patients with a baseline BPI-SF or RSCL assessment were included, and data from the two study treatment arms were combined for all analyses.

The associations between baseline measures of clinician-assessed KPS and patient-assessed BPI-SF and RSCL subscale scores were analyzed using one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA). Univariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine the prognostic effect of each variable on survival. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to determine the prognostic effect of each RSCL and BPI-SF score in the presence of 11 baseline demographic and clinical prognostic factors that had been used in the clinical study for randomization stratification or preplanned subgroup analyses. In general, a finding of an effect in a univariate analysis is sufficient to show that the subscale provides prognostic information for survival; the same finding in a multivariate analysis suggests that the prognostic value is additional to what could be obtained from demographic and clinical characteristics. For the current analysis, all were assessed as binary categorical variables: KPS (<90 vs ≥90), estrogen receptor status (positive vs negative), progesterone receptor status (positive vs negative), presence of visceral disease (yes vs no), age (<65 vs ≥65), prior radiotherapy (yes vs no), prior hormonal treatment (yes vs no), menopausal status (pre- or peri-menopausal vs post-menopausal), basis for pathologic diagnosis (histological vs cytological), race (Caucasian vs non-Caucasian), and pathologic diagnosis (ductal vs non-ductal). Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests were used to compare survival among patient groups categorized into three and two categories for the BPI-SF [56] and the RSCL respectively. The categories of the BPI-SF were divided into approximately equal numbers of patients: worst pain scores (0 = no pain, 1 to 4 = mild pain, 5 to 10 = moderate/severe pain), pain interference scores (0 to <0.5 = no interference, ≥0.5 to <4.5 = mild interference, ≥4.5 to ≤10 = moderate/severe interference). Dichotomized patient groups (>median, ≤ median) were evaluated for each of the four RSCL subscale scores; a choice of baseline median as the cut point was made by the study team so as to evaluate similar numbers of patients above and below the median. Statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05, and no adjustment was made for multiplicity. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS® version 9.2 or later version.

Results

Patient population and baseline characteristics

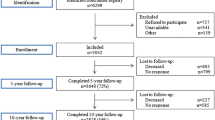

Table 1 shows the baseline demographic and disease characteristics of patients who contributed data to this analysis. This analysis included all patients who completed the BPI-SF (n = 286) and RSCL (n = 336) questionnaires at baseline. Approximately one-third to one-half of patients in the original study did not complete these assessments primarily due to a lack of a validated translation of the questionnaire in their language [46]. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics were comparable between those who completed the BPI-SF or the RSCL, with the majority of patients less than 65 years of age, post-menopausal, Caucasian, and having metastatic disease at diagnosis. Additionally, similar proportions of patients in each group were estrogen or progesterone receptor positive or negative, had ductal or non-ductal breast carcinoma, and received prior radiotherapy or hormonal therapy. The number of patients eligible to complete the RSCL based on validated translations was 368. However, 32 patients did not complete the RSCL at baseline due to failure by the site to administer (n = 11), patient refusal (n = 11), or other reasons, the specifics of which were not documented (n = 10). The number of patients eligible to complete the BPI based on validated translations was 308. Of these, 22 patients did not complete the BPI at baseline due to failure by the site to administer (n = 8), patient refusal (n = 9), or other reasons (n = 5).

Association of the BPI-SF and RSCL Scores with KPS

Given the role of clinician-assessed performance status as a clinical measure in these patients, we sought to specifically characterize the association between patient-assessed BPI-SF and RSCL versus KPS. Both BPI-SF variables (pain interference and worst pain) were significantly associated with KPS (pain interference p ≤ 0.0001; worst pain p = 0.0030). Patients with better performance status (higher KPS) had less pain interference and less intensity of worst pain (Table 2). There was a positive association between mean RSCL subscale scores and KPS for activity level, physical distress, and overall HRQOL, indicating that patients with better performance status had greater levels of activity and HRQOL as well as lower levels of physical distress (all p < 0.0001, Table 3). While there was a positive trend in RSCL scores with increasing KPS, there was no significant association between KPS and the psychological distress subscale (p = 0.1630).

Prognostic Effect of BPI-SF and RSCL on Survival

In the univariate analyses, patients with higher BPI-SF scores (indicating worse pain or pain interference) had lower survival rates. In the case of the RSCL, patients with higher scores (indicating lower symptom burden) had better survival. Significant prognostic effects on survival were observed for baseline scores of both BPI-SF worst pain and pain interference (both hazard ratios [HRs], 1.07 for 1-point increase; both p ≤ 0.0061) and three of the four RSCL subscales (activity level, physical distress, and overall HRQOL) (HR, 0.86–0.91 for 10-point increase; all p ≤ 0.0104; Table 4). Psychological distress had no significant prognostic effect on survival.

In the multivariate analyses, the BPI-SF worst pain item and the RSCL activity level remained significant prognostic factors (p = 0.0342, p = 0.0004, respectively; Table 4) in the presence of the 11 baseline demographic or clinical variables. The pain interference subscale, physical distress, and overall HRQOL scores were no longer significant. Consistent with the univariate analysis, psychological distress was not prognostic for survival.

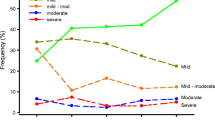

Survival Time by BPI-Worst Pain, Pain Interference, and RSCL Categories

The median survival time for patients with a BPI-SF worst pain score of 0 (no pain) was 23.8 months (n = 91), versus 17.9 months (n = 94) for scores 1–4, and 14.6 months (n = 94) for scores 5–10 (log-rank p = 0.0065, Fig. 1a). Median survival time for patients with BPI-SF pain interference scores was 21.2 months (n = 113) (no pain; scores 0 to <0.5) versus 17.6 months (n = 111) (scores ≥0.5 to <4.5) and 14.8 months (n = 58) (scores ≥4.5 to ≤10; log-rank p = 0.0107; Fig. 1b). The median survival time was 23.8 months for patients with median (95.2) or greater activity level scores versus 14.6 months for patients with scores below median (log-rank p < 0.0001, Fig. 2). Similarly, for the activity, physical, psychological, and HRQOL subscales, patients with median or greater scores had significantly better survival (log-rank p < 0.05, Fig. 2).

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves by Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (RSCL) Categories. a. Activity Level. b. Physical Distress. c. Psychological Distress. d. Overall Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL). * Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine each hazard ratio (HR) in the presence of 11 demographic/clinical variables: age, race, KPS, estrogen receptor status, progesterone receptor status, presence of visceral disease, prior radiotherapy, prior hormonal treatment, menopausal status, basis for pathological diagnosis, and pathological diagnosis. Reference is the < median group; Q50 is the median of each RSCL subscale

Discussion

We have shown in this post hoc analysis that baseline patient-reported outcomes and symptoms, as measured by the BPI-SF and RSCL, were prognostic for survival in patients with locally recurrent or metastatic breast carcinoma who received gemcitabine with or without paclitaxel. The use of two different, validated instruments was informative when exploring this prognostic effect in that they measure distinct aspects of HRQOL in cancer patients [57], and the present study allowed for a model-dependent sensitivity analysis.

In this study, the worst pain and pain interference measures of the BPI-SF as well as activity level, physical distress, and HRQOL scores of the RSCL were all prognostic for survival in the univariate analysis. The BPI-SF worst pain and RSCL activity subscales retained a statistically significant effect in the multivariate analysis, which incorporated clinical, and sociodemographic variables commonly used as prognostic indicators in advanced breast cancer (Table 4). Clinical factors previously reported as prognostic via multivariate analysis for this study cohort included time from diagnosis to randomization, number of tumor sites, estrogen receptor status, and KPS [40].

The RSCL activity subscale had the greatest effect on survival, as reflected by the hazard ratio in the univariate analysis (Table 4). In addition, it was the only subscale to retain a statistically significant effect in the multivariate analysis that considered the other RSCL subscales as well as baseline clinical or demographic characteristics. The RSCL psychological distress subscale had no relationship with survival based on 10-point increments in a Cox proportional hazards model (Table 4). However, the dichotomous comparison (above and below median scores) did reveal a significant difference in survival curves (log-rank p = 0.0109; Fig. 2). It is important to note that systematic literature reviews have found only minimal evidence for prognostic effects of psychosocial HRQOL domains on cancer survival [7, 58].

The most commonly utilized instruments in MBC trials include the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B) and the EORTC QLQ-C30 with or without the EORTC breast cancer-specific module, QLQ-BR23 [59]; positive prognostic results have been demonstrated in previously reported analyses of advanced breast cancer that used baseline EORTC QLC-C30 assessments [27–29].

The current exploratory analysis of a clinical study population further adds to the body of evidence that patient-reported outcomes and symptoms can be prognostic indicators in patients with advanced breast cancer and as such, a useful adjunct for informing the routine care of patients. It is important to note that because patient-reported responses can be subject to social and environmental factors, this information is best used as an added tool to all other demographic and clinical considerations that are part of patient care [9]. The reasons for the relationship between patient-reported outcomes and symptoms, and survival have not been completely elucidated. However, it is thought that patient-reported outcomes may be sensitive to disease progression or markers of patient behaviors or other characteristics, such as treatment adherence or healthy lifestyles [7]. In addition, the inclusion of multiple items in patient survey instruments may enhance their diagnostic sensitivity whether in clinical management or in oncology drug trials [7].

It is important to reiterate that the current study was a post hoc analysis of HRQOL data originally recorded as secondary outcomes in a prospective clinical trial [46]. Although not all randomized patients were included in the analyses due to limited availability of translations of the BPI-SF and RSCL, a high percentage of the patients with translations available to them completed the questionnaires; furthermore because only baseline questionnaire responses were used, there was less potential for nonrandom missing data. Prognostic factors in the current study were not defined prior to study enrollment, and no adjustments were made for multiplicity. Therefore, it would be worthwhile to evaluate the hypothesis prospectively in order to further support the utility of patient-survey instruments for the added benefit of assessing patient prognosis both in clinical trials as well as in routine clinical practice. If confirmed, these data could be used to potentially identify appropriate cut points for the purposes of prognostic evaluation and study stratification. It is important to reiterate that these findings are specific to first-line advanced disease and cannot be generalized to other lines of therapy. Furthermore, results discordant with those of other studies may have been due to differences in statistical techniques or instrumentation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this post hoc analysis of patients with advanced breast cancer showed that pretreatment BPI-SF worst pain and RSCL activity scores provide additional prognostic information for survival beyond that available from standard demographic and clinical characteristics. Our findings further support the concept that patient-reported outcomes can be useful additional prognostic factors in advanced breast cancer and help guide effective clinical decision making by revealing manifestations of malignant disease not systematically evaluated by formal clinical measures.

Abbreviations

- BPI-SF:

-

Brief Pain Inventory Short Form

- EORTC QLQ-C30:

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30

- HR:

-

hazard ratio.

- HRQOL:

-

health related quality of life

- KPS:

-

Karnofsky Performance Status

- MBC:

-

metastatic breast cancer

- RSCL:

-

Rotterdam Symptom Checklist

References

American Cancer Society. Global Cancer Facts & Figures 2nd Edition. American Cancer Society, Atlanta. 2011. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-027766.pdf. Accessed 4 Aug, 2014.

Benson JR, Jatoi I. The global breast cancer burden. Future Oncol. 2012;8:697–702.

Swain S, Kim S, Cortes J, J. R, Semiglazov V, Campone M, et al. 350O_PR - Final overall survival (OS) analysis from the CLEOPATRA study of first-line (1 L) pertuzumab (Ptz), trastuzumab (T), and docetaxel (D) in patients (pts) with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (MBC). European Society for Medical Oncology; 28.09.2014; Madrid, Spain 2014.

Tan SH, Wolff AC. Treatment of Metastatic Breast Cancer: Chemotherapy. In: Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne CK, editors. Diseases of the Breast, vol. 74. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 2010. p. 877–919.

Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:32.

Ganz PA. Survivorship: adult cancer survivors. Prim Care. 2009;36:721–41.

Gotay CC, Kawamoto CT, Bottomley A, Efficace F. The prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1355–63.

Sullivan PW, Nelson JB, Mulani PM, Sleep D. Quality of life as a potential predictor for morbidity and mortality in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1297–306.

Lohr KN, Zebrack BJ. Using patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: challenges and opportunities. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:99–107.

Detmar SB, Aaronson NK. Quality of life assessment in daily clinical oncology practice: a feasibility study. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(8):1181–6.

Velikova G, Brown JM, Smith AB, Selby PJ. Computer-based quality of life questionnaires may contribute to doctor-patient interactions in oncology. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:51–9.

Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, Brown PM, Lynch P, Brown JM, et al. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:714–24.

Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, Wever LD, Aaronson NK. Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:3027–34.

Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, Harrow A, Di Domenico D, Croy S, et al. What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1480–501.

Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, Scher HI, Hudis CA, Sabbatini P, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:557–65.

Howell D, Molloy S, Wilkinson K, Green E, Orchard K, Wang K, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer clinical practice: a scoping review of use, impact on health outcomes, and implementation factors. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(9):1846–58.

Cardoso F, Senkus-Konefka E, Fallowfield L, Costa A, Castiglione M. Locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 Suppl 5:v15–9.

Moinpour CM, Feigl P, Metch B, Hayden KA, Meyskens Jr FL, Crowley J. Quality of life end points in cancer clinical trials: review and recommendations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:485–95.

Nieder C, Mehta MP. Prognostic indices for brain metastases--usefulness and challenges. Radiat Oncol. 2009;4:10.

Wagner LI, Wenzel L, Shaw E, Cella D. Patient-reported outcomes in phase II cancer clinical trials: lessons learned and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5058–62.

Hahn EA, Cella D, Chassany O, Fairclough DL, Wong GY, Hays RD, et al. Precision of health-related quality-of-life data compared with other clinical measures. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1244–54.

Sprangers MA. Disregarding clinical trial-based patient-reported outcomes is unwarranted: Five advances to substantiate the scientific stringency of quality-of-life measurement. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:155–63.

Quinten C, Martinelli F, Coens C, Sprangers MA, Ringash J, Gotay C, et al. A global analysis of multitrial data investigating quality of life and symptoms as prognostic factors for survival in different tumor sites. Cancer. 2014;120:302–11.

Reck M, Thatcher N, Smit EF, Lorigan P, Szutowicz-Zielinska E, Liepa AM, et al. Baseline quality of life and performance status as prognostic factors in patients with extensive-stage disease small cell lung cancer treated with pemetrexed plus carboplatin vs. etoposide plus carboplatin. Lung Cancer. 2012;78:276–81.

Quinten C, Coens C, Mauer M, Comte S, Sprangers MA, Cleeland C, et al. Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:865–71.

Coates A, Gebski V, Signorini D, Murray P, McNeil D, Byrne M, et al. Prognostic value of quality-of-life scores during chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer. Australian New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1833–8.

Efficace F, Biganzoli L, Piccart M, Coens C, Van Steen K, Cufer T, et al. Baseline health-related quality-of-life data as prognostic factors in a phase III multicentre study of women with metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:1021–30.

Kramer JA, Curran D, Piccart M, de Haes JC, Bruning P, Klijn J, et al. Identification and interpretation of clinical and quality of life prognostic factors for survival and response to treatment in first-line chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1498–506.

Svensson H, Hatschek T, Johansson H, Einbeigi Z, Brandberg Y. Health-related quality of life as prognostic factor for response, progression-free survival, and survival in women with metastatic breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2012;29:432–8.

Gupta D, Granick J, Grutsch JF, Lis CG. The prognostic association of health-related quality of life scores with survival in breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:387–93.

Staren ED, Gupta D, Braun DP. The prognostic role of quality of life assessment in breast cancer. Breast J. 2011;17:571–8.

Collette L, van Andel G, Bottomley A, Oosterhof GO, Albrecht W, de Reijke TM, et al. Is baseline quality of life useful for predicting survival with hormone-refractory prostate cancer? A pooled analysis of three studies of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genitourinary Group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3877–85.

Chang VT, Thaler HT, Polyak TA, Kornblith AB, Lepore JM, Portenoy RK. Quality of life and survival: the role of multidimensional symptom assessment. Cancer. 1998;83:173–9.

Chau I, Norman AR, Cunningham D, Waters JS, Oates J, Ross PJ. Multivariate prognostic factor analysis in locally advanced and metastatic esophago-gastric cancer--pooled analysis from three multicenter, randomized, controlled trials using individual patient data. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2395–403.

Efficace F, Bottomley A, Smit EF, Lianes P, Legrand C, Debruyne C, et al. Is a patient’s self-reported health-related quality of life a prognostic factor for survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients? A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of EORTC study 08975. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1698–704.

McKernan M, McMillan DC, Anderson JR, Angerson WJ, Stuart RC. The relationship between quality of life (EORTC QLQ-C30) and survival in patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:888–93.

Movsas B, Moughan J, Sarna L, Langer C, Werner-Wasik M, Nicolaou N, et al. Quality of life supersedes the classic prognosticators for long-term survival in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: an analysis of RTOG 9801. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5816–22.

Sloan JA, Zhao X, Novotny PJ, Wampfler J, Garces Y, Clark MM, et al. Relationship between deficits in overall quality of life and non-small-cell lung cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1498–504.

Tan AD, Novotny PJ, Kaur JS, Buckner JC, Schaefer PL, Stella PJ, et al. A patient-level meta-analytic investigation of the prognostic significance of baseline quality of life (QOL) for overall survival (OS) among 3,704 patients participating in 24 North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) and Mayo Clinic Cancer Center (MC) oncology clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2007;26(Suppl1):9515.

Albain KS, Nag SM, Calderillo-Ruiz G, Jordaan JP, Llombart AC, Pluzanska A, et al. Gemcitabine plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel monotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer and prior anthracycline treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3950–7.

Cleeland C. The Brief Pain Inventory: A Users Guide. 2009. http://www.mdanderson.org/education-and-research/departments-programs-and-labs/departments-and-divisions/symptom-research/symptom-assessment-tools/BPI_UserGuide.pdf. Accessed. 2 Sept, 2014.

Twelves CJ, Dobbs NA, Lawrence MA, Ramirez AJ, Summerhayes M, Richards MA, et al. Iododoxorubicin in advanced breast cancer: a phase II evaluation of clinical activity, pharmacology and quality of life. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:726–31.

Del Mastro L, Fabi A, Mansutti M, De Laurentiis M, Durando A, Merlo DF, et al. Randomised phase 3 open-label trial of first-line treatment with gemcitabine in association with docetaxel or paclitaxel in women with metastatic breast cancer: a comparison of different schedules and treatments. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:164.

Ramirez AJ, Towlson KE, Leaning MS, Richards MA, Rubens RD. Do patients with advanced breast cancer benefit from chemotherapy? Br J Cancer. 1998;78:1488–94.

Hopwood P, Watkins J, Ellis P, Smith I. Clinical interpretation of quality-of-life outcomes: an investigation of data from the randomized trial of gemcitabine plus paclitaxel compared with paclitaxel alone for advanced breast cancer. Breast J. 2008;14:228–35.

Moinpour CM, Donaldson GW, Liepa AM, Melemed AS, O’Shaughnessy J, Albain KS. Evaluating health-related quality-of-life therapeutic effectiveness in a clinical trial with extensive nonignorable missing data and heterogeneous response: results from a phase III randomized trial of gemcitabine plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel monotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:765–75.

Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129–38.

de Haes JC, Olschewski M, Fayres P, Visser MRM, Cull A, Hopwood P, et al. Measuring the Quality of Life of Cancer Patients With the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (RSCL): A Manual. Groningen, The Netherlands: Northern Centre for Healthcare Research (NCH); 2012.

Watson M, Law M, Maguire GP, Robertson B, Greer S, Bliss JM, et al. Further development of a quality of life measure for cancer patients: The Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (revised). Psycho-Oncology. 1992;1:35–44.

de Haes JC, Olschewski M. Quality of life assessment in a cross-cultural context: use of the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist in a multinational randomised trial comparing CMF and Zoladex (Goserlin) treatment in early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:745–50.

Bailey AJ, Parmar MK, Stephens RJ. Patient-reported short-term and long-term physical and psychologic symptoms: results of the continuous hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy (CHART) randomized trial in non-small-cell lung cancer. CHART Steering Committee. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3082–93.

Chiarion-Sileni V, Del Bianco P, De Salvo GL, Lo Re G, Romanini A, Labianca R, et al. Quality of life evaluation in a randomised trial of chemotherapy versus bio-chemotherapy in advanced melanoma patients. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1577–85.

Duncan GG, Philips N, Pickles T. Report on the quality of life analysis from the phase III trial of pion versus photon radiotherapy in locally advanced prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:759–65.

Hopwood P, Harvey A, Davies J, Stephens RJ, Girling DJ, Gibson D, et al. Survey of the Administration of quality of life (QL) questionnaires in three multicentre randomised trials in cancer. The Medical Research Council Lung Cancer Working Party the CHART Steering Committee. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:49–57.

Ribi K, Bernhard J, Schuller JC, Weder W, Bodis S, Jorger M, et al. Individual versus standard quality of life assessment in a phase II clinical trial in mesothelioma patients: feasibility and responsiveness to clinical changes. Lung Cancer. 2008;61:398–404.

Cleeland CS, Nakamura Y, Mendoza TR, Edwards KR, Douglas J, Serlin RC. Dimensions of the impact of cancer pain in a four country sample: new information from multidimensional scaling. Pain. 1996;67:267–73.

Kemmler G, Holzner B, Kopp M, Dunser M, Margreiter R, Greil R, et al. Comparison of two quality-of-life instruments for cancer patients: the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2932–40.

Montazeri A. Quality of life data as prognostic indicators of survival in cancer patients: an overview of the literature from 1982 to 2008. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:102.

Lemieux J, Goodwin PJ, Bordeleau LJ, Lauzier S, Theberge V. Quality-of-life measurement in randomized clinical trials in breast cancer: an updated systematic review (2001–2009). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:178–231.

Acknowledgements

The study, the development of this manuscript, and article processing charge were supported by Eli Lilly and Company. We thank Zhanglin Lin Cui and Jiaying Guo of Eli Lilly and Company for their assistance in statistical analysis. We also thank David Hartree of ClinGenuity, LLC, Cincinnati, USA, for writing assistance, which was supported by Eli Lilly and Company.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

ENS, WS, LB, PP, WJ, AM, and AML are employees and shareholders at Eli Lilly and Company.

Authors’ contributions

WS and LB originated the concept and design of the study; WS performed data acquisition; WS, PP, LB, and ENS were responsible for statistical analyses/interpretation; ENS and WS drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Smyth, E.N., Shen, W., Bowman, L. et al. Patient-reported pain and other quality of life domains as prognostic factors for survival in a phase III clinical trial of patients with advanced breast cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 14, 52 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0449-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0449-z