Abstract

Anopheles mosquitoes present a major public health challenge in sub-Saharan Africa; notably, as vectors of malaria that kill over half a million people annually. In parts of the east and southern Africa region, one species in the Funestus group, Anopheles funestus, has established itself as an exceptionally dominant vector in some areas, it is responsible for more than 90% of all malaria transmission events. However, compared to other malaria vectors, the species is far less studied, partly due to difficulties in laboratory colonization and the unresolved aspects of its taxonomy and systematics. Control of An. funestus is also increasingly difficult because it has developed widespread resistance to public health insecticides. Fortunately, recent advances in molecular techniques are enabling greater insights into species identity, gene flow patterns, population structure, and the spread of resistance in mosquitoes. These advances and their potential applications are reviewed with a focus on four research themes relevant to the biology and control of An. funestus in Africa, namely: (i) the taxonomic characterization of different vector species within the Funestus group and their role in malaria transmission; (ii) insecticide resistance profile; (iii) population genetic diversity and gene flow, and (iv) applications of genetic technologies for surveillance and control. The research gaps and opportunities identified in this review will provide a basis for improving the surveillance and control of An. funestus and malaria transmission in Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria transmission is driven by female Anopheles mosquitoes. In Africa, the four major malaria vectors are Anopheles gambiae, Anopheles coluzzii, Anopheles arabiensis, and Anopheles funestus sensu stricto (s.s.). Different Anopheles species exhibit contrasting behaviours and physiological responses to interventions, such as insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS), which are the core World Health Organization (WHO)-recommended vector control methods [1]. For instance, An. gambiae, An. coluzzii, and An. funestus s.s. predominantly prefer blood-feeding on humans (anthropophilic) and resting indoors (endophilic) [2, 3], whereas An. arabiensis is a more generalist vector, biting humans but also readily feeding on domestic animals (zoophilic) and resting both outdoors (exophilic) and indoors [4]. However, some evidence indicates that An. funestus s.s. is shifting resting and feeding behaviour to the outdoors [5] and sometimes during daytime in some settings as an adaptation to indoor interventions [6]. Models predict such behavioural shifts coupled with vector resistance could have devastating public health outcomes [7]. Additionally, such innate or evolving differences in behaviours between vector species mean that interventions can have differential effects depending on local vector ecology.

Anopheles funestus s.s., hereafter referred to as An. funestus, is emerging as one of the most important malaria vectors and is increasingly dominant even in areas where it co-occurs with the other prominent vector species. For instance, in certain parts of Tanzania, An. funestus contributes consistently more than 90% of the yearly entomological inoculation rate (EIR) even in areas where it is far less abundant than An. arabiensis [8,9,10,11]. A similar trend of vectorial dominance has been observed in Cameroon where the vector contributes over 70% EIR in certain villages [12, 13], in Burkina Faso where it seasonally dominates transmission [14], and in Malawi [15], Zambia [16], and Kenya [17] where it is established as the primary malaria vector. Given the observed competence of An. funestus in the East and Southern Africa and in parts of Central and West Africa, it might be reasonable to generate a continent-wide comparative assessment on the importance of An. funestus in malaria transmission in different settings.

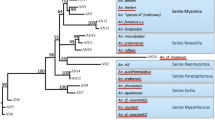

Anopheles funestus belongs to the An. funestus group of mosquitoes, hereafter referred to as AFG, which has at least 10 other African sibling species, namely: An. funestus-like, Anopheles parensis, Anopheles vaneedeni, Anopheles aruni, Anopheles confusus, Anopheles leesoni, Anopheles longipalpis, Anopheles rivulorum, An. rivulorum-like, Anopheles brucei, and Anopheles fuscivenosus [18]. Some of these species are morphologically indistinguishable at the adult stage, though experienced entomologists can distinguish some species at the aquatic stage using identification keys [18]. Collectively, the AFG mosquitoes have a wide geographical distribution across sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 1). Anopheles funestus, An. leesoni and An. rivulorum occur in most tropical Africa, while An. parensis, An. confusus, and An. aruni are localized to eastern African countries. Anopheles vaneedeni, An. parensis, An. fuscivenosus, An. funestus-like and An. longipalpis are native to southern African countries, while An. rivulorum-like and An. brucei are also frequent in West and Central Africa [19,20,21]. Within the AFG, An. funestus is considered the main malaria vector across Africa due to its preferentially anthropophilic nature [22] and having the highest malaria infection rates [10]. However, other members in this group have also been shown to be naturally infected by malaria parasites. For instance, An. rivulorum were observed to be active early in the night, outdoors, and were found to be carrying Plasmodium falciparum in Tanzania and Kenya [23, 24]. Similar observations have been made on An. longipalpis in Kenya [25], An. vaneedeni in South Africa [26], and An. parensis in Uganda [27] and South Africa [28] where they are considered to contribute to residual malaria transmission. While An. funestus is likely the most important vector in this group in most settings, others may play a role as secondary vectors. Thus, it is important to ensure accurate and robust methodologies to distinguish members of this group as required to assess their relative contribution to residual transmission.

The distribution of the Anopheles funestus group in Africa. The red areas indicate countries with the confirmed presence of at least one member in the group while the blue area indicates areas where the species is not yet recorded. The map was created in R software (v 4.2.1) and QGIS (v 3.18) using raster data sourced from the Malaria Atlas Project (https://malariaatlas.org/)

In many countries, malaria vector control is also increasingly difficult because of widespread resistance to public health insecticides [29]. Compared to other malaria vectors, An. funestus populations are increasingly surviving diagnostic doses of pyrethroids in bioassays [30]. Experimental work has shown that the increasing resistance in this vector significantly reduces the effectiveness of ITNs [31]. Despite the elusiveness of quantifying the impact of vector resistance on malaria epidemiology at the community level [32], recent data from an area with highly resistant An. funestus as the primary vector [8, 33] indicates the superiority of dual active ITNs compared to standard ITNs in reducing malaria cases, suggesting a key role of resistant An. funestus in malaria transmission [34]. As physiological resistance continues to spread in Africa, it is important to understand its underlying mechanisms to inform more effective control strategies. Since the spread of resistance genes in mosquito populations is influenced by gene flow [35], population genetics using whole genome sequencing provides unique insights into the structure of malaria vectors, as recently shown in An. gambiae [36]. This approach also opens avenues for discovering new resistance mechanisms [37] and could generate essential information for the development and deployment of genetic control tools such as gene drives [38].

Previous reviews have outlined recent advances in characterizing chromosomal inversion and the development of PCR molecular diagnostic assays for An. funestus [39], and the advances in insecticide resistance profiling and population genetics of An. funestus [40]. However, despite a significant increase in research on these topics over the last ten years, there has not been a recent review publication of current knowledge on the molecular basis of insecticide resistance, gene flow patterns, and fine-scale population structuring of An. funestus. This is warranted as advances in molecular techniques in the last decade can enable greater insights into the real identity of vector species and how the resistance genotypes are spreading within and between mosquito population clusters. There have also been recent improvements in the An. funestus reference genome [41, 42], which can provide newer insights into the genetic basis of the mosquitoes' behavioural and physiological attributes.

A selection of these advances and their potential applications are reviewed along four key research themes relevant to the biology and control of An. funestus in Africa, as follows: (i) taxonomic and systematic characterization of the vector, its sibling species, and their roles in malaria transmission in different settings; (ii) improvements in insecticide resistance profiling and associated technologies; (iii) improved understanding of the genetic structure and gene flow patterns between and within population clusters of the vector species, and (iv) potential applications of genetic technologies for surveillance and control of the species. The review provides a basis for identifying key research gaps and opportunities for an R&D agenda relevant to the surveillance and control of An. funestus and malaria transmission.

Molecular approaches to identify members of the An. funestus group

Morphological keys for the identification of members of the AFG and other African Anopheles mosquitoes were established between 1968 [43], then updated in 1987 [44], and more recently updated in 2020 with an improved description of many Anopheles species complexes and groups [18]. This method of identification requires well-trained taxonomists, and either field collection of aquatic stages that are reared to the adult stage, which takes between 2 and 4 weeks, or trap collection of adults. Even when samples suitable for morphological identification are available, some members of the AFG are challenging to distinguish taxonomically at either stage, necessitating the adoption of molecular methods (Table 1).

Before 1990, Anopheles identification was primarily done by a combination of morphological characterization [44] and cytogenetic analysis of chromosomal inversions [45,46,47]. Cytogenic analysis is however a tedious process, stage and sex-specific, and requires semi-gravid females [47]. Efforts to develop molecular diagnostics for the An. funestus group began in the 1990s with a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) coupled with restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP) targeting the 28S ribosomal gene to distinguish between An. funestus and An. vaneedeni [48]. This was later expanded to a single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) assay, targeting the same gene, to distinguish An. funestus, An. vaneedeni, An. rivulorum, and An. leesoni [49]. Overlap in DNA banding patterns between the renatured and denatured single strands necessitated the development of a further assay, targeting ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2), to distinguish the two medically important vectors, An. funestus and An. rivulorum [50]. This eventually laid the ground for the development of the AFG multiplex PCR assay, which is a cocktail PCR assay that can distinguish five members (An. funestus, An. rivulorum, An. vaneedeni, An. leesoni, and An. parensis) of the AFG in a single run [51]. However, an initial challenge observed with the AFG multiplex PCR assay, was that its performance was not generalizable to some parts of Africa, especially Central and West Africa where it could not readily identify An. rivulorum [52]. Further analysis revealed the presence of An. rivulorum-like as a separate species [52], which was later also confirmed in South Africa [21]. Similarly in Malawi, the AFG multiplex PCR assay failed to identify samples morphologically characterized into the AFG but were later designated as An. funestus-like by using cytogenesis and DNA-based methods [53]. Following these discoveries, the AFG multiplex PCR assay has since been expanded to include species-specific primers for An. funestus-like and An. rivolurum-like.

Given several challenges in AFG species identification, it is key to combine different approaches, such as morphological and molecular data that could be used together with geographical location data to infer the species. For example, although An. leesoni is closely related to the Asian vector Anopheles minimus, it is considered a separate species based on its geographical separation. Similarly, and indeed an often-neglected challenge is the inclusion of non-AFG samples in a diagnostic PCR assay, which may erroneously identify them as a member of the AFG [54]. For example, a member of the Anopheles marshalli group or An. gambiae complex mistakenly included in the AFG multiplex PCR assay would be erroneously identified as An. leesoni [54]). Therefore, careful sample handling and morphological identification are key to improving this analysis. Accurate species identification is also critical for epidemiological studies, for example, the malaria parasite was recently reported from An. longipalpis C, considered not to be a malaria vector [55], and a molecularly unidentified cryptic species within the AFG [23]; similarly to findings in cryptic species within the An. gambiae complex [56]. These new findings highlight the need to acknowledge mosquito species whose identity is not fully resolved as potential vectors and the need for field estimates of malaria transmission to incorporate the Anopheles species found in an area more broadly. Lastly, the employment of vector genomic surveillance, even on a small scale, should be established as part of routine national vector monitoring programmes. Country-level investments are, therefore, necessary to enhance training for control programmes to better integrate taxonomy and molecular techniques to improve species identification and incrimination.

Population genetics of An. funestus

Understanding mosquito populations enables the assessment of the feasibility and potential impact of genetic control approaches such as gene drives for disease control. It also provides a basis for monitoring the spread of genetic traits such as insecticide-resistance alleles. Molecular techniques ranging from chromosomal inversions, mitochondrial DNA analysis, restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP), microsatellite genotyping, and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) have been employed to provide insights into patterns of An. funestus population interactions and structuring [57,58,59,60]. The utility of these techniques in advancing studies in An. funestus population genetics are highlighted below.

Chromosomal inversions

Chromosomal inversions in mosquitoes are important drivers of local adaptation to varying environmental factors [61, 62]. This is important for An. funestus that has both a wide geographical range across Africa (Fig. 1) and high levels of chromosomal polymorphisms [39]. The technique for studying inversions was developed in the 1970s and follows a process where the ovaries of half-gravid females are squashed, stained, and observed under a phase contrast microscope to reveal the polytene chromosomes [47], which are then scored using a chromosome map developed by Sharakhov et al. [63].

Costantini et al. first identified two chromosomal forms of An. funestus in Burkina Faso, namely Kiribina and Folonzo, based on 3Ra, 3Rb, and 2Ra inversions [60, 64]. The Kiribina form is distinguished by an inversion in the 2R and 3R chromosomes, while Folonzo has inversions 3Ra and 3Rb [60]. Both ecotypes are sympatric, highly anthropophilic, and contribute significantly to malaria transmission in their localities [64]. In Cameroon, Folonzo was found to occupy the equatorial zones of the country while Kiribina occupied the dry savannah regions [65]. Similarly, Ayala et al. found differentiation in chromosomal inversions in An. funestus collected from different ecologies in the same country [66] with the inversions causing a reduction in nucleotide diversity resulting in overall low genetic differentiation among the ecotypes [67]. In Angola, five inversions were detected, 2Ra, 2Rh, 3Ra, 3Rb, and 3La, with only samples from central Angola (Huambo province) designated as Folonzo chromosomal forms [68]. Taken together, these studies suggest an important association between chromosomal inversions and adaptation to diverse ecological conditions, which might be contributing to the spatial and temporal extension of malaria transmission [69].

Cytogenic karyotyping is still largely based on a tedious technique that requires highly skilled personnel and cannot be used on mosquito life stages other than gravid females, thus constraining the scalability of its use. Hence, a genotyping assay has recently been developed that utilizes tag single nucleotide polymorphisms (tag SNP) on the 3Ra, 3Rb, and 2Ra inversions to distinguish different An. funestus ecotypes [70]. This new method has a high agreement with the traditional cytogenic karyotyping method and can be deployed on any mosquito life stage, making it more convenient for high throughput cytogenic studies. However, this method has some limitations as current tag-SNPs are suitable only for distinguishing between the two West-African ecotypes of An. funestus, Folonzo and Kiribina. Additional innovation will be necessary to develop high-throughput techniques that can be used for broader analyses of chromosomal inversions across the continent; especially in an era where genomic sequence data are increasingly available. This will enable investigation of how these inversions might influence vector dispersal and adaptability in the face of climate change.

Mitochondrial DNA analysis

Analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is useful in reconstructing mosquito phylogenetic relationships, molecular evolution, and understanding their population history, i.e. time of taxon divergence [71]. For example, Michel et al. analyzed partial mitochondrial genes, NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 5 protein (ND5) and Cytochrome c oxidase I (COI), from 11 countries across Africa, showing that An. funestus is genetically grouped into Eastern, Western, and Central populations, and detected two lineages I and II [59], defined as a group of mosquitoes that are ancestrally connected by using maternally inherited mitochondrial genes. Whilst lineage I was widespread across sub-Saharan Africa, lineage II was found restricted to mosquitoes from Tanzania, Madagascar, Zambia, and Mozambique [58, 59, 72] (Fig. 2). Similarly, Jones et al. [73] analysed 43 complete mitochondrial genomes of An. funestus from Zambia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Tanzania, identifying 41 unique haplotypes, comprising 567 polymorphisms. This study also detected two distinct yet partially sympatric, lineages of An. funestus, lineage I and II, estimating their divergence to half a million years ago. An analysis of these lineages in the context of plausible introgression within the AFG indicates a genetic exchange between An. parensis and An. funestus before its rapid geographic range expansion [74]. Recently, a PCR-based diagnostic using hydrolysis probe analysis has been developed to identify these lineages in field-collected samples [75] that could be expanded to improve the identification of lineages in An. funestus.

Restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP) of ribosomal DNA

Geographical barriers to gene flow such as the Great Rift Valley have been hypothesized to influence how mosquitoes interact in space and time, shaping their population structure and adaptation. An RFLP analysis of a variable domain (D3) of the 28S ribosomal nuclear DNA in An. funestus mosquitoes sampled from either the eastern or western sides of the Rift Valley found different RFLP profiles; specifically W, M, and MW-types in the West, East, and Southern African countries respectively [58]. Notably, samples from Malawi, which is at the southern tip of the Rift Valley, had all the Y, Z, M, W, and MW genotypes (Fig. 2), suggesting that major landscape features could be guiding the directional flow and geographical convergence of genes in mosquito populations and shaping their genetic profiles. Natural barriers to gene flow other than the Rift Valley, such as wildlife reserves and forests, urban landscapes, lakes, and, mountain ranges, should also be investigated to assess their effect on An. funestus diversity.

Microsatellite genotyping analysis

Once An. funestus microsatellite markers were physically mapped [63, 76], they became the indicator of choice for studying population diversity, gene flow patterns, migration rates, population size, bottlenecks, and kinship. These markers are robust due to their codominant nature, neutrality, random repeats across genomes, and conformity to Mendelian inheritance [77].

Continentally, microsatellite analysis shows that An. funestus subdivides into eastern, western, and central African genetic populations, broadly consistent with mitochondrial DNA patterns, but offering clearer resolution [59]. Genetic diversity studies in southern African countries have revealed finer scale variation. Barnes et al. analysed samples from Malawi, Zambia, and Mozambique and found strong North–South segregation within mosquitoes from Malawi and Zambia, indicating high levels of gene flow [78]. However, within Malawi, they also found high FST values between southern populations when compared to those in the north, indicating the presence of a gene flow barrier [78]. Analysis of additional An. funestus samples from Uganda and Zimbabwe later corroborated the same diversity observed in the southern African region [79]. In Kenya, An. funestus collected from the western part of the country were found to be genetically distinct from coastal populations [80]; similar to the pattern observed previously using chromosomal inversion analysis [81]. These studies implicate the Rift Valley as a possible barrier to gene flow between populations. Genetic structuring has also been observed within and between island An. funestus populations in Comoros and Madagascar [82]. Ayala et al. found samples from the two islands to cluster separately but also observed in-country structure within Madagascar, which might be driven by landscape features. As An. funestus undergoes speciation across the continent, the role of these observed diversities should be investigated on how they influence vector adaptation, dispersal, and potential vectorial capacity.

Whole genome sequence analysis

Currently, WGS studies investigating population diversity in An. funestus are rare in contrast with the extensive investigation that has been done on the An. gambiae complex [36, 56]. However, this is likely to change rapidly given the rise of collaborative programs such as the recent inception of the MalariaGEN Anopheles funestus genomic surveillance project (https://www.malariagen.net/projects/anopheles-funestus-genomic-surveillance-project) which is sequencing samples of this species from across Africa. A recent success of this program is the improved genome assembly from an individual female An. funestus (specimen from Gabon; 251 megabases) complete with the mitochondrial genome (15.4 kilobases) [41].

Genomic analysis has cross cutting potential of providing new insights into the genetic diversity of mosquito vectors, improving the surveillance of vectors and insecticide resistance, and providing an open resource for the development of new control tools. For example sequence analysis of An. funestus collected across Africa has shown Southern African mosquitoes to cluster separately from other African populations [57] with a similar clustering pattern found using microsatellite analysis suggesting a barrier to gene flow [83]. Several WGS in the An. gambiae complex have shown its potential. For example, genome-wide sequence analysis in the An. gambiae complex showed that An. coluzzii is largely restricted to West Africa whilst West, Central, and Eastern An. gambiae are genetically similar [56]. Additionally, WGS in the An. gambiae complex has revealed new mechanisms of insecticide resistance and associated alleles such as copy number variants [37].

Thus, WGS analysis on An. funestus has the potential of discovering fine-scale population structuring which is vital for elucidating population history and the spread of insecticide-resistance genes across the region. Unlike other approaches such as the use of microsatellites, WGS can allow delineation of more recent genetic changes in a population. However, from a practical perspective, simpler options involving specific amplicons are likely to be more widely used given their quicker turnaround times. WGS will remain an important research tool, but is unlikely to be practiced at scale.

Insecticide resistance profiling in Anopheles funestus

Five classes of insecticides are recommended for the control of adult Anopheles vectors: pyrethroids, carbamates, organophosphates, organochlorines, and neonicotinoids. Given the limited options within these classes, and the widespread insecticide resistance [29], control programs need integrated measures to monitor phenotypic insecticide susceptibility and underlying resistance mechanisms to select appropriate insecticide products for the management of resistance.

Bioassays to determine phenotypic resistance are conducted following either the WHO or Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) bottle assays; in which mosquitoes are exposed to standard concentrations of an insecticide and either mortality or knock-down measured after a specific time [84]. The mechanisms of resistance responsible for resistance phenotypes include metabolic detoxification [85], target site mutations [86], cuticular thickening which reduces insecticide penetration [87], or behavioural avoidance to reduce exposure to insecticides [88].

Metabolic resistance

Metabolic resistance occurs when a mosquito produces high levels of detoxifying enzymes that chemically modify and deactivate the insecticides. Three families of metabolizing enzymes are associated with resistance: esterase, monooxygenases, and glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs) [89].

Increased expression of monooxygenase enzymes belonging to the cytochrome P450 gene family (CYP450) is the most common cause of resistance to pyrethroids in An. funestus [31, 57, 85, 90, 91] Table 2. The expression of these genes varies considerably across Africa reflecting possible barriers to gene flow amongst populations [31, 57, 78]. For instance, the CYP450 genes CYP6P9a, CYP6M7, and CYP6P9b are overexpressed (i.e., exhibit elevated transcription compared to susceptible strains) in An. funestus resistant populations in southern African populations from Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique [31, 91, 92]. In contrast, the CYP450 genes CYP6M4, CYP9K1, CYP6P9b, CYP304b1, CYP6N1, CYP6M1, CYP6Z1, and CYP6M7 are overexpressed in resistant populations from Uganda and Tanzania in East Africa [93,94,95]. Recently, CYP6Z1 has also been shown to confer carbamate and pyrethroid cross-resistance in the laboratory [96] though further field evaluation is needed.

In West Africa (Benin and Nigeria), the CYP450 CYP6P9a, CYP6P9b, and a glutathione S-transferase gene family (GSTe2) are overexpressed in resistant An. funestus mosquitoes and confer pyrethroid and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) cross-resistance [97,98,99]. However, overexpression of CYP6P9a was not subsequently detected in West African samples in an analysis by Weedall et al. [58], indicating this mechanism may be restricted to East and Southern African countries. Similarly, overexpression of CYP6P4a appears to be restricted to Ghana, and CYP6P5 overexpression is only found in East and West African samples [57]. In East and West African An. funestus populations overexpression of CYP6P9a/b, and glutathione S-transferase epsilon (GSTE-L119F) genes confer resistance to DDT [99, 100]. Contrastingly, in southern African countries, An. funestus populations remain susceptible to DDT insecticides [101, 102]. This demonstrates how diverse the genes involved in metabolic resistance across the continent are with CYP6P9a/b having a continental distribution.

Despite the crucial role of CYP450 and GSTs genes in mediating insecticide resistance in An. funestus, simplified and field-applicable DNA-based assays for tracking metabolic resistance have not been available for this species. An assay for field tracking CYP6P9a in An. funestus has only recently been developed [31]. The assay is based on PCR–RFLP where a Taq I restriction enzyme cuts a 450 bp region of CYP6P9a-resistant mosquitoes but not in susceptible ones, allowing the distinction [31]. Such assays can easily advance monitoring of resistance alleles in the field without requiring sophisticated equipment, however, they might not be straightforward to design, depending on the genetic basis of the resistance. Considering the ubiquity of these resistance genes, the DNA-based assays should have a multigene panel approach where the most common genes can be amplified in the same assay.

Target site resistance

Target-site resistance is caused by point mutations in insecticide-binding proteins which thereby inhibit the binding and toxic activity of the insecticide. The most widely studied target site mutation is knockdown resistance (kdr), which is based on a point mutation changing leucine to phenylalanine or serine at codon 1014 (995 using An. gambiae codon numbering) of the voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) in An. gambiae mosquitoes. The mutation reduces sensitivity to pyrethroids and DDT [103]. However, analysis of VGSC gene at the 1014 codon has not detected any mutation in An. funestus [104, 105]. This suggests that kdr might not be involved in DDT and pyrethroid cross-resistance in An. funestus [86, 103]. Other non-synonymous mutations in the VGSC gene in An. funestus such as I877L, V881L, and A1007S have been detected, and though require further investigation, do not appear to have a substantial impact on insecticide resistance [105].

Despite dieldrin not currently being used for vector control, An. funestus resistance to this insecticide remains high, especially in Central and West Africa. This is caused by an A296S-rdl mutation in γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-gated chloride channel in An. funestus from West Africa (Burkina Faso), Central Africa (Cameroon), and Southern Africa (Malawi), but not in East Africa [15, 106, 107] (Table 2). The mutation is likely to persist in the population even in absence of selection pressure due to its chromosomal location, that is close to the centromere, which reduces any cross-over event [107, 108]. Organophosphate resistance in An. gambiae and An. coluzzii, is driven by a G280S/G119S ace-1 mutation [109, 110], with little known in An. funestus. There is a need for research to understand the resistance mechanism of the commonly used IRS insecticide (pirimiphos-methyl), even though it remains efficacious against An. funestus [111].

The evolution of resistance in An. funestus populations primarily through metabolic resistance mechanism via P450s, makes them liable to cross-resistance with other insecticides. Looking into the future, the use of the WGS approach has the potential of discovering novel resistance mechanisms in An. funestus whilst also providing new insights into genes already implicated in resistance. In An. gambiae and Aedes aegypti, for instance, this technique has led to the discovery of a new resistance mechanism through gene duplication or copy number variation (CNV) in metabolic resistance genes [37, 112]. Copy number variations can lead to resistance, as the presence of more copies of a detoxifying gene will result in its overexpression [113]. As WGS costs are decreasing, its application for An. funestus resistance monitoring should be prioritized.

The potential of genetic technologies for the surveillance and control of An. funestus

Genetic manipulation of disease vectors involves the deliberate release of individuals containing a desirable genetic trait to spread it through the wild-type population via mating [114]. Such approaches can include either population suppression through the spread of genes reducing vector reproduction, or modification of vector by introducing genes that confer refractoriness to pathogens [115]. Many of these gene drive approaches are based on the use of CRISPR-Cas9-based elements that can copy themselves from one chromosome to another in the germline and thereby increase their representation among the gametes. This type of approach ensures accuracy and super Mendelian inheritance leading to a rapid increase in the frequency of the desired traits in the target population [116,117,118,119].

The development of CRISPR-based genome editing tools and gene drives in Anopheles mosquitoes rapidly advanced over the past six years albeit with a focus on mosquitoes of the An. gambiae complex [38, 116]. However, a more holistic gene drive programme for malaria control will need to equally target the increasingly important African malaria vector, An. funestus. Fortunately, the transgenic pipelines and technologies that are already established for An. gambiae can be adapted to this species.

Only a handful of studies have been published that demonstrate the use of gene editing technologies in An. funestus [120, 121]. Using CRISPR/Cas9, Li et al. [124] showed for the first time that heritable germline mutations could be introduced into An. funestus genome by microinjection of guide RNAs (gRNAs) and Cas9 protein into eggs. This resulted in a stable colony that can be used for reverse genetics studies. This was achieved through a nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) repair process, following Cas9 cleavage of a target site that is determined by the sequence of the gRNA, which leads to small insertions or deletions. Quinn et al. [123] have also recently demonstrated the successful use of homology-directed repair (HDR), also known as knock-in, for the generation of transgenic An. funestus. HDR has the advantage of introducing the desired transgenic DNA sequence that is incorporated into the mosquito germline during the repair process. Since the copying mechanism of HDR is like what many of the CRISPR-based gene-drive rely on to increase their copy number, the high rates of HDR observed in An. funestus to date augur well for its amenability to gene drives of this type.

Assuming successful development of gene-drive constructs for An. funestus, several entomological and regulatory questions will need to be addressed before large-scale deployment. A major challenge is the mass rearing of modified An. funestus mosquitoes under laboratory settings. Currently, there are only two colony lines of the vector successfully established in the laboratory, An. funestus from Mozambique (FUMOZ) and An. funestus from southern Angola (FANG) [122, 123]. This is mainly due to the bottlenecks of adapting An. funestus into a laboratory colony which includes larval survival, mating success in cages, and low adult survival rates [124]. Overcoming these challenges will be key to establishing transgenic colony lines in the laboratory for experimentation and large-scale vector control use.

Additionally, the high levels of genetic diversity within An. funestus populations across Africa could impact the application of gene drive control strategies [57, 59, 78]. Sex-linked gene drive approaches are dependent on gene flow which is shaped by natural barriers such as large water bodies, large forests cover, aridity, valleys, and mountains [36]. Hence, fine-scale population genetics surveys of populations at target release sites must be undertaken as an integral part of the deployment strategy. Overall, the application of gene drives will need to be tailored depending on the local vector population and environmental and geographical features [125]. Similarly, it will be vital to resolve regulatory issues around ethics, and environmental impact, and importantly allow the communities living in malaria-endemic areas to have a leading voice in the development and deployment of such tools [126, 127].

Conclusion

The last decade has seen an upsurge in An. funestus group research to understand mechanisms of insecticide resistance, taxonomy, and population biology. A combination of robust morphological identification, allele-specific PCR, and small-scale WGS should be used in tandem with geographical information when profiling mosquito identity. Cytochrome P450-mediated metabolic resistance starkly varies across the continent hence the development of field adaptable DNA-based assay to diagnose it should be a priority to help in resistance management and surveillance. Similarly, a detailed analysis of An. funestus population genetics should be undertaken on how it influences the spread of resistance genotypes and as a prerequisite to the deployment of genetic control tools. Attempts at malaria control and elimination need to be holistic bringing together current and emerging vector control approaches, a pool of empowered human personnel, and most importantly involving communities who bear the burden of this disease.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AFG:

-

An. funestus Group

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- IRS:

-

Indoor residual spraying

- ITN:

-

Insecticide treated net

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- RFLP:

-

Restriction fragment length polymorphism

- WGS:

-

Whole-genome sequencing

- NHEJ:

-

Nonhomologous end-joining

- HDR:

-

Homology-directed repair

References

WHO. Guidelines for malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022.

Akogbeto MC, Salako AS, Dagnon F, Aikpon R, Kouletio M, Sovi A, et al. Blood feeding behaviour comparison and contribution of Anopheles coluzzii and Anopheles gambiae, two sibling species living in sympatry, to malaria transmission in Alibori and Donga region, northern Benin, West Africa. Malar J. 2018;17:307.

Kabbale FG, Akol AM, Kaddu JB, Onapa AW. Biting patterns and seasonality of Anopheles gambiae sensu lato and Anopheles funestus mosquitoes in Kamuli District, Uganda. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:340.

Tirados I, Costantini C, Gibson G, Torr SJ. Blood-feeding behaviour of the malarial mosquito Anopheles arabiensis: implications for vector control. Med Vet Entomol. 2006;20:425–37.

Kreppel KS, Viana M, Main BJ, Johnson PCD, Govella NJ, Lee Y, et al. Emergence of behavioural avoidance strategies of malaria vectors in areas of high LLIN coverage in Tanzania. Sci Rep. 2020;10:14527.

Sougoufara S, Diédhiou SM, Doucouré S, Diagne N, Sembène PM, Harry M, et al. Biting by Anopheles funestus in broad daylight after use of long-lasting insecticidal nets: a new challenge to malaria elimination. Malar J. 2014;13:125.

Sherrard-Smith E, Skarp JE, Beale AD, Fornadel C, Norris LC, Moore SJ, et al. Mosquito feeding behavior and how it influences residual malaria transmission across Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:15086–95.

Matowo NS, Martin J, Kulkarni MA, Mosha JF, Lukole E, Isaya G, et al. An increasing role of pyrethroid-resistant Anopheles funestus in malaria transmission in the Lake Zone. Tanzania Sci Rep. 2021;11:13457.

Kakilla C, Manjurano A, Nelwin K, Martin J, Mashauri F, Kinung’hi SM, et al. Malaria vector species composition and entomological indices following indoor residual spraying in regions bordering Lake Victoria, Tanzania. Malar J. 2020;19:383.

Kaindoa EW, Matowo NS, Ngowo HS, Mkandawile G, Mmbando A, Finda M, et al. Interventions that effectively target Anopheles funestus mosquitoes could significantly improve control of persistent malaria transmission in south-eastern Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2017;12: e0177807.

Lwetoijera D, Harris C, Kiware S, Dongus S, Devine GJ, McCall PJ, et al. Effective autodissemination of pyriproxyfen to breeding sites by the exophilic malaria vector Anopheles arabiensis in semi-field settings in Tanzania. Malar J. 2014;13:1.

Djamouko-Djonkam L, Nkahe DL, Kopya E, Talipouo A, Ngadjeu CS, Doumbe-Belisse P, et al. Implication of Anopheles funestus in malaria transmission in the city of Yaounde, Cameroon. Parasite. 2020;27:10.

Cohuet A, Simard F, Wondji CS, Antonio-Nkondjio C, Awono-Ambene P, Fontenille D. High malaria transmission intensity due to Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) in a village of savannah-forest transition area in Cameroon. J Med Entomol. 2004;41:901–5.

Soma DD, Zogo BM, Some A, Tchiekoi BN, Hien DFS, Pooda HS, et al. Anopheles bionomics, insecticide resistance and malaria transmission in southwest Burkina Faso: a pre-intervention study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0236920.

Riveron JM, Chiumia M, Menze BD, Barnes KG, Irving H, Ibrahim SS, et al. Rise of multiple insecticide resistance in Anopheles funestus in Malawi: a major concern for malaria vector control. Malar J. 2015;14:344.

Stevenson JC, Pinchoff J, Muleba M, Lupiya J, Chilusu H, Mwelwa I, et al. Spatio-temporal heterogeneity of malaria vectors in northern Zambia: implications for vector control. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:510.

McCann RS, Ochomo E, Bayoh MN, Vulule JM, Hamel MJ, Gimnig JE, et al. Reemergence of Anopheles funestus as a vector of Plasmodium falciparum in Western Kenya after long-term implementation of insecticide-treated bed nets. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:597–604.

Coetzee M. Key to the females of Afrotropical Anopheles mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Malar J. 2020;19:70.

Dia I, Guelbeogo MW, Ayala D. Advances and perspectives in the study of the malaria mosquito Anopheles funestus. In: Manguin S, editor. Anopheles mosquitoes—new insights into malaria vectors. London: IntechOpen; 2013.

Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S, Rubio-Palis Y, Chareonviriyaphap T, Coetzee M, et al. A global map of dominant malaria vectors. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:69.

Mouatcho J, Cornel AJ, Dahan-Moss Y, Koekemoer LL, Coetzee M, Braack L. Detection of Anopheles rivulorum-like, a member of the Anopheles funestus group, in South Africa. Malar J. 2018;17:195.

Takken W, Verhulst NO. Host preferences of blood-feeding mosquitoes. Annu Rev Entomol. 2013;58:433–53.

Kinya F, Mutero CM, Sang R, Owino EA, Rotich G, Ogola EO, et al. Outdoor malaria vector species profile in dryland ecosystems of Kenya. Sci Rep. 2022;12:7131.

Wilkes TJ, Matola YG, Charlwood JD. Anopheles rivulorum a vector of human malaria in Africa. Med Vet Entomol. 1996;10:108–10.

Ogola EO, Fillinger U, Ondiba IM, Villinger J, Masiga DK, Torto B, et al. Insights into malaria transmission among Anopheles funestus mosquitoes, Kenya. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:577.

Burke A, Dandalo L, Munhenga G, Dahan-Moss Y, Mbokazi F, Ngxongo S, et al. A new malaria vector mosquito in South Africa. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43779.

Mulamba C, Irving H, Riveron JM, Mukwaya LG, Birungi J, Wondji CS. Contrasting Plasmodium infection rates and insecticide susceptibility profiles between the sympatric sibling species Anopheles parensis and Anopheles funestus s.s.: a potential challenge for malaria vector control in Uganda. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:71.

Burke A, Dahan-Moss Y, Duncan F, Qwabe B, Coetzee M, Koekemoer L, et al. Anopheles parensis contributes to residual malaria transmission in South Africa. Malar J. 2019;18:257.

Ranson H, Lissenden N. Insecticide resistance in African Anopheles mosquitoes: a worsening situation that needs urgent action to maintain malaria control. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:187–96.

Pinda PG, Eichenberger C, Ngowo HS, Msaky DS, Abbasi S, Kihonda J, et al. Comparative assessment of insecticide resistance phenotypes in two major malaria vectors, Anopheles funestus and Anopheles arabiensis in south-eastern Tanzania. Malar J. 2020;19:408.

Weedall GD, Mugenzi LMJ, Menze BD, Tchouakui M, Ibrahim SS, Amvongo-Adjia N, et al. A cytochrome P450 allele confers pyrethroid resistance on a major African malaria vector, reducing insecticide-treated bednet efficacy. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaat7386.

Kleinschmidt I, Bradley J, Knox TB, Mnzava AP, Kafy HT, Mbogo C, et al. Implications of insecticide resistance for malaria vector control with long-lasting insecticidal nets: a WHO-coordinated, prospective, international, observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:640–9.

Matowo NS, Kulkarni MA, Messenger LA, Jumanne M, Martin J, Mallya E, et al. Differential impact of dual-active ingredient long-lasting insecticidal nets on primary malaria vectors: a secondary analysis of a 3-year, single-blind, cluster-randomised controlled trial in rural Tanzania. Lancet Planet Health. 2023;7:e370–80.

Mosha JF, Kulkarni MA, Lukole E, Matowo NS, Pitt C, Messenger LA, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness against malaria of three types of dual-active-ingredient long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) compared with pyrethroid-only LLINs in Tanzania: a four-arm, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2022;399:1227–41.

Caprio MA, Tabashnik BE. Gene flow accelerates local adaptation among finite populations: simulating the evolution of insecticide resistance. J Econ Entomol. 1992;85:611–20.

Anopheles gambiae Genomes Consortium, Data Analysis Group, Partner Working Group, Sample Collections, Crosses, Sequencing and Data Production, et al. Genetic diversity of the African malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Nature. 2017;552:96–100.

Lucas ER, Miles A, Harding NJ, Clarkson CS, Lawniczak MKN, Kwiatkowski DP, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals high complexity of copy number variation at insecticide resistance loci in malaria mosquitoes. Genome Res. 2019;29:1250–61.

Hammond A, Pollegioni P, Persampieri T, North A, Minuz R, Trusso A, et al. Gene-drive suppression of mosquito populations in large cages as a bridge between lab and field. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4589.

Coetzee M, Fontenille D. Advances in the study of Anopheles funestus, a major vector of malaria in Africa. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:599–605.

Coetzee M, Koekemoer LL. Molecular systematics and insecticide resistance in the major African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Annu Rev Entomol. 2013;58:393–412.

Ayala D, Akone-Ella O, Kengne P, Johnson H, Heaton H, Collins J, et al. The genome sequence of the malaria mosquito, Anopheles funestus, Giles, 1900. Wellcome Open Res. 2023;7:287.

Ghurye J, Koren S, Small ST, Redmond S, Howell P, Phillippy AM, et al. A chromosome-scale assembly of the major African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Gigascience. 2019;8:giz063.

Gillies MT. The Anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara. Publ Sth Afr Inst Med Res. 1968. p. 1–343.

Gillies MT, Coetzee M. A supplement to the Anophelinae of the South of the Sahara (Afrotropical Region). Publ S Afr Inst Med Res. 1987;55:1–143.

Green CA, Hunt RH. Interpretation of variation in ovarian polytene chromosomes of Anopheles funestus Giles, Anopheles parensis Gillies and Anopheles aruni? Genetica. 1980;51:187–95.

Mahon RJ, Green CA, Hunt RH. Diagnostic allozymes for routine identification of adults of the Anopheles gambiae complex (Diptera, Culicidae). Bull Entomol Res. 1976;66:25–31.

Hunt RH. A cytological technique for the study of Anopheles gambiae complex. Parassitologia. 1973;15:137–9.

Koekemoer LL, Coetzee M, Hunt RH. HpaII endonuclease distinguishes between two species in the Anopheles funestus group. Insect Mol Biol. 1998;7:273–7.

Koekemoer LL, Lochouarn L, Hunt RH, Coetzee M. Single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis for identification of four members of the Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group. J Med Entomol. 1999;36:125–30.

Hackett BJ, Gimnig J, Guelbeogo W, Costantini C, Koekemoer LL, Coetzee M, et al. Ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) sequences differentiate Anopheles funestus and An. rivulorum, and uncover a cryptic taxon. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9:369–74.

Koekemoer LL, Kamau L, Hunt RH, Coetzee M. A cocktail polymerase chain reaction assay to identify members of the Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:804–11.

Cohuet A, Simard F, Toto J-C, Kengne P, Coetzee M, Fontenille D. Species identification within the Anopheles funestus group of malaria vectors in Cameroon and evidence for a new species. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:200–5.

Spillings BL, Brooke BD, Koekemoer LL, Chiphwanya J, Coetzee M, Hunt RH. A new species concealed by Anopheles funestus Giles, a major malaria vector in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:510–5.

Erlank E, Koekemoer LL, Coetzee M. The importance of morphological identification of African anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) for malaria control programmes. Malar J. 2018;17:43.

Kent RJ, Coetzee M, Mharakurwa S, Norris DE. Feeding and indoor resting behaviour of the mosquito Anopheles longipalpis in an area of hyperendemic malaria transmission in southern Zambia. Med Vet Entomol. 2006;20:459–63.

Clarkson CS, Miles A, Harding NJ, Lucas ER, Battey CJ, Amaya-Romero JE, Kern AD, Fontaine MC, Donnelly MJ, Lawniczak MK, Kwiatkowski DP. Genome variation and population structure among 1142 mosquitoes of the African malaria vector species Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii. Genome Res. 2020;30:1533–46.

Weedall GD, Riveron JM, Hearn J, Irving H, Kamdem C, Fouet C, et al. An Africa-wide genomic evolution of insecticide resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus involves selective sweeps, copy number variations, gene conversion and transposons. PLoS Genet. 2020;16: e1008822.

Koekemoer LL, Kamau L, Garros C, Manguin S, Hunt RH, Coetzee M. Impact of the Rift valley on restriction fragment length polymorphism typing of the major African Malaria vector Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2006;43:1178–84.

Michel AP, Ingrasci MJ, Schemerhorn BJ, Kern M, Le Goff G, Coetzee M, et al. Rangewide population genetic structure of the African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:4235–48.

Costantini C, Sagnon N, Ilboudo-Sanogo E, Coluzzi M, Boccolini D. Chromosomal and bionomic heterogeneities suggest incipient speciation in Anopheles funestus from Burkina Faso. Parassitologia. 1999;41:595–611.

Hoffmann AA, Willi Y. Detecting genetic responses to environmental change. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:421–32.

Kirkpatrick M, Barton N. Chromosome inversions, local adaptation and speciation. Genetics. 2006;173:419–34.

Sharakhov I, Braginets O, Grushko O, Cohuet A, Guelbeogo WM, Boccolini D, et al. A microsatellite map of the African human malaria vector Anopheles funestus. J Hered. 2004;95:29–34.

Guelbeogo WM, Sagnon NF, Liu F, Besansky NJ, Costantini C. Behavioural divergence of sympatric Anopheles funestus populations in Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2014;13:65.

Cohuet A, Dia I, Simard F, Raymond M, Rousset F, Antonio-Nkondjio C, et al. Gene flow between chromosomal forms of the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in Cameroon, Central Africa, and its relevance in malaria fighting. Genetics. 2005;169:301–11.

Ayala D, Fontaine MC, Cohuet A, Fontenille D, Vitalis R, Simard F. Chromosomal inversions, natural selection and adaptation in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:745–58.

Kamdem C, Fouet C, White BJ. Chromosome arm-specific patterns of polymorphism associated with chromosomal inversions in the major African malaria vector, Anopheles funestus. Mol Ecol. 2017;26:5552–66.

Boccolini D, Carrara GC, Dia I, Fortes F, Cani PJ, Constantini C. Chromosomal differentiation of Anopheles funestus from Luanda and Huambo provinces, western and central Angola. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:1071–6.

Fontenille D, Simard F. Unravelling complexities in human malaria transmission dynamics in Africa through a comprehensive knowledge of vector populations. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;27:357–75.

Lukindu M, Love RR, Guelbeogo MW, Small ST, Stephens MT, Campbell NR, et al. High-throughput genotyping of common chromosomal inversions in the Afrotropical malaria mosquito Anopheles funestus. Insects. 2020;11:693.

Krzywinski J, Grushko OG, Besansky NJ. Analysis of the complete mitochondrial DNA from Anopheles funestus: an improved dipteran mitochondrial genome annotation and a temporal dimension of mosquito evolution. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;39:417–23.

Choi KS, Koekemoer LL, Coetzee M. Population genetic structure of the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus s.s. and allied species in Southern Africa. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:283.

Jones CM, Lee Y, Kitchen A, Collier T, Pringle JC, Muleba M, et al. Complete Anopheles funestus mitogenomes reveal an ancient history of mitochondrial lineages and their distribution in southern and central Africa. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9054.

Small ST, Labbe F, Lobo NF, Koekemoer LL, Sikaala CH, Neafsey DE, et al. Radiation with reticulation marks the origin of a major malaria vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:31583–90.

Choi KS, Coetzee M, Koekemoer LL. Detection of clade types (clades i and II) within Anopheles funestus sensu stricto by the hydrolysis probe analysis (Taqman assay). Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:173.

Wondji CS, Hunt RH, Pignatelli P, Steen K, Coetzee M, Besansky N, et al. An integrated genetic and physical map for the malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Genetics. 2005;171:1779–87.

Selkoe KA, Toonen RJ. Microsatellites for ecologists: a practical guide to using and evaluating microsatellite markers. Ecol Lett. 2006;9:615–29.

Barnes KG, Irving H, Chiumia M, Mzilahowa T, Coleman M, Hemingway J, et al. Restriction to gene flow is associated with changes in the molecular basis of pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:286–91.

Kaddumukasa MA, Wright J, Muleba M, Stevenson JC, Norris DE, Coetzee M. Genetic differentiation and population structure of Anopheles funestus from Uganda and the southern African countries of Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:87.

Ogola EO, Odero JO, Mwangangi JM, Masiga DK, Tchouassi DP. Population genetics of Anopheles funestus, the African malaria vector, Kenya. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:15.

Kamau L, Hunt R, Coetzee M. Analysis of the population structure of Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) from Western and Coastal Kenya using paracentric chromosomal inversion frequencies. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:78–83.

Ayala D, Goff GL, Robert V, de Jong P, Takken W. Population structure of the malaria vector Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Madagascar and Comoros. Acta Trop. 2006;97:292–300.

Barnes KG, Weedall GD, Ndula M, Irving H, Mzihalowa T, Hemingway J, et al. Genomic footprints of selective sweeps from metabolic resistance to pyrethroids in African malaria vectors are driven by scale up of insecticide-based vector control. PLoS Genet. 2017;13: e1006539.

WHO. Manual for monitoring insecticide resistance in mosquito vectors and selecting appropriate interventions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022.

Wondji CS, Irving H, Morgan J, Lobo NF, Collins FH, Hunt RH, et al. Two duplicated P450 genes are associated with pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles funestus, a major malaria vector. Genome Res. 2009;19:452–9.

Martinez-Torres D, Chandre F, Williamson MS, Darriet F, Berge JB, Devonshire AL, et al. Molecular characterization of pyrethroid knockdown resistance (kdr) in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol Biol. 1998;7:179–84.

Wood O, Hanrahan S, Coetzee M, Koekemoer L, Brooke B. Cuticle thickening associated with pyrethroid resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Parasit Vectors. 2010;4(3):67.

Gatton ML, Chitnis N, Churcher T, Donnelly MJ, Ghani AC, Godfray HCJ, et al. The importance of mosquito behavioural adaptations to malaria control in Africa. Evolution. 2013;67:1218–30.

Hemingway J, Ranson H. Insecticide resistance in insect vectors of human disease. Annu Rev Entomol. 2000;45:371–91.

Djuicy DD, Hearn J, Tchouakui M, Wondji MJ, Irving H, Okumu FO, et al. CYP6P9-Driven signatures of selective sweep of metabolic resistance to pyrethroids in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus reveal contemporary barriers to gene flow. Genes (Basel). 2020;11:1314.

Riveron JM, Ibrahim SS, Chanda E, Mzilahowa T, Cuamba N, Irving H, et al. The highly polymorphic CYP6M7 cytochrome P450 gene partners with the directionally selected CYP6P9a and CYP6P9b genes to expand the pyrethroid resistance front in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in Africa. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:817.

Christian RN, Strode C, Ranson H, Coetzer N, Coetzee M, Koekemoer LL. Microarray analysis of a pyrethroid resistant African malaria vector, Anopheles funestus, from southern Africa. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2011;99:140–7.

Sandeu MM, Mulamba C, Weedall GD, Wondji CS. A differential expression of pyrethroid resistance genes in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus across Uganda is associated with patterns of gene flow. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0240743.

Morgan JC, Irving H, Okedi LM, Steven A, Wondji CS. Pyrethroid resistance in an Anopheles funestus population from Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2010;5: e11872.

Matowo J, Weetman D, Pignatelli P, Wright A, Charlwood JD, Kaaya R, et al. Expression of pyrethroid metabolizing P450 enzymes characterizes highly resistant Anopheles vector species targeted by successful deployment of PBO-treated bednets in Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2022;17: e0249440.

Ibrahim SS, Ndula M, Riveron JM, Irving H, Wondji CS. The P450 CYP6Z1 confers carbamate/pyrethroid cross-resistance in a major African malaria vector beside a novel carbamate-insensitive N485I acetylcholinesterase-1 mutation. Mol Ecol. 2016;25:3436–52.

Tchigossou GM, Atoyebi SM, Akoton R, Tossou E, Innocent D, Riveron J, et al. Investigation of DDT resistance mechanisms in Anopheles funestus populations from northern and southern Benin reveals a key role of the GSTe2 gene. Malar J. 2020;19:456.

Atoyebi SM, Tchigossou GM, Akoton R, Riveron JM, Irving H, Weedall G, et al. Investigating the molecular basis of multiple insecticide resistance in a major malaria vector Anopheles funestus (sensu stricto) from Akaka-Remo, Ogun State, Nigeria. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:423.

Tchigossou G, Djouaka R, Akoton R, Riveron JM, Irving H, Atoyebi S, et al. Molecular basis of permethrin and DDT resistance in an Anopheles funestus population from Benin. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:602.

Mulamba C, Riveron JM, Ibrahim SS, Irving H, Barnes KG, Mukwaya LG, et al. Widespread pyrethroid and DDT resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus in East Africa is driven by metabolic resistance mechanisms. PLoS ONE. 2014;9: e110058.

Ippolito MM, Gebhardt ME, Ferriss E, Schue JL, Kobayashi T, Chaponda M, et al. Scientific findings of the southern and central Africa international center of excellence for malaria research: ten years of malaria control impact assessments in hypo-, meso-, and holoendemic transmission zones in Zambia and Zimbabwe. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2022;107(4):55–67.

Casimiro S, Coleman M, Mohloai P, Hemingway J, Sharp B. Insecticide resistance in Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) from Mozambique. J Med Entomol. 2006;43:267–75.

Ranson H, Jensen B, Vulule JM, Wang X, Hemingway J, Collins FH. Identification of a point mutation in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of Kenyan Anopheles gambiae associated with resistance to DDT and pyrethroids. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9:491–7.

Irving H, Wondji CS. Investigating knockdown resistance (kdr) mechanism against pyrethroids/DDT in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus across Africa. BMC Genet. 2017;18:76.

Menze BD, Riveron JM, Ibrahim SS, Irving H, Antonio-Nkondjio C, Awono-Ambene PH, et al. Multiple insecticide resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus from northern Cameroon is mediated by metabolic resistance alongside potential target site insensitivity mutations. PLoS ONE. 2016;11: e0163261.

Amvongo-Adjia N, Riveron JM, Njiokou F, Wanji S, Wondji CS. Influence of a major mountainous landscape barrier (mount Cameroon) on the spread of metabolic (GSTe2) and target-Site (Rdl) resistance alleles in the African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Genes (Basel). 2020;11:1492.

Wondji CS, Dabire RK, Tukur Z, Irving H, Djouaka R, Morgan JC. Identification and distribution of a GABA receptor mutation conferring dieldrin resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in Africa. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;41:484–91.

Brooke BD, Hunt RH, Chandre F, Carnevale P, Coetzee M. Stable chromosomal inversion polymorphisms and insecticide resistance in the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2002;39:568–73.

Ibrahim SS, Muhammad A, Hearn J, Weedall GD, Nagi SC, Mukhtar MM, et al. Molecular drivers of insecticide resistance in the Sahelo-Sudanian populations of a major malaria vector Anopheles coluzzii. BMC Biol. 2023;21:125.

Grau-Bove X, Lucas E, Pipini D, Rippon E, Hof van’t AE, Constant E, et al. Resistance to pirimiphos-methyl in West African Anopheles is spreading via duplication and introgression of the Ace1 locus. PLoS Genet. 2021;17:e1009253.

Abong’o B, Gimnig JE, Torr SJ, Longman B, Omoke D, Muchoki M, et al. Impact of indoor residual spraying with pirimiphos-methyl (Actellic 300CS) on entomological indicators of transmission and malaria case burden in Migori County, western Kenya. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4518.

Faucon F, Dusfour I, Gaude T, Navratil V, Boyer F, Chandre F, et al. Identifying genomic changes associated with insecticide resistance in the dengue mosquito Aedes aegypti by deep targeted sequencing. Genome Res. 2015;25:1347–59.

Bass C, Field LM. Gene amplification and insecticide resistance. Pest Manag Sci. 2011;67:886–90.

James AA. Gene drive systems in mosquitoes: rules of the road. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:64–7.

Bier E. Gene drives gaining speed. Nat Rev Genet. 2022;23:5–22.

Hammond A, Galizi R, Kyrou K, Simoni A, Siniscalchi C, Katsanos D, et al. A CRISPR-Cas9 gene drive system targeting female reproduction in the malaria mosquito vector Anopheles gambiae. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:78–83.

Gantz VM, Jasinskiene N, Tatarenkova O, Fazekas A, Macias VM, Bier E, et al. Highly efficient Cas9-mediated gene drive for population modification of the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E6736–43.

Esvelt KM, Smidler AL, Catteruccia F, Church GM. Concerning RNA-guided gene drives for the alteration of wild populations. Elife. 2014;3: e03401.

Burt A. Site-specific selfish genes as tools for the control and genetic engineering of natural populations. Proc Biol Sci. 2003;270(1518):921–8.

Quinn C, Anthousi A, Wondji C, Nolan T. CRISPR-mediated knock-in of transgenes into the malaria vector Anopheles funestus. (G3) Bethesda. 2021;11:jkab201.

Li M, Akbari OS, White BJ. Highly efficient site-specific mutagenesis in malaria mosquitoes using CRISPR. G3 (Bethesda). 2018;8:653–8.

Hunt RH, Brooke BD, Pillay C, Koekemoer LL, Coetzee M. Laboratory selection for and characteristics of pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Med Vet Entomol. 2005;19:271–5.

Hargreaves K, Koekemoer LL, Brooke BD, Hunt RH, Mthembu J, Coetzee M. Anopheles funestus resistant to pyrethroid insecticides in South Africa. Med Vet Entomol. 2000;14:181–9.

Ngowo HS, Hape EE, Matthiopoulos J, Ferguson HM, Okumu FO. Fitness characteristics of the malaria vector Anopheles funestus during an attempted laboratory colonization. Malar J. 2021;20:148.

Eckhoff PA, Wenger EA, Godfray HC, Burt A. Impact of mosquito gene drive on malaria elimination in a computational model with explicit spatial and temporal dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E255–64.

WHO. Guidance framework for testing of genetically modified mosquitoes. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

James S, Collins FH, Welkhoff PA, Emerson C, Godfray HCJ, Gottlieb M, et al. Pathway to deployment of gene drive mosquitoes as a potential biocontrol tool for elimination of malaria in Sub-Saharan Africa: recommendations of a scientific working group. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98(6):1–49.

Choi KS, Coetzee M, Koekemoer LL. Simultaneous identification of the Anopheles funestus group and Anopheles longipalpis type C by PCR-RFLP. Malar J. 2010;9:316.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alex J. Limwagu for his help in developing the map on Fig. 2, and Tony Nolan for his initial reviews and comments on the manuscript.

Funding

Funding support was received from Howard Hughes Medical Institute-Gates Foundation International Research Scholar Award (grant no. OPP 1099295) to FO. Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (grant no. INV-002138) to FO, FB, HMF. Academy Medical Science Springboard Award (ref: SBF007\100094) to FB. DST/NRF South African Research Chairs Initiative Grant (UID 64763) to LLK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JOO, HMF, FOO, and FB designed the manuscript framework and scope. JOO wrote the first and subsequent drafts of the manuscript. HMF, FOO, DW and FB played supervision role during writing and reviewing of the manuscript. All authors participated in reviewing and approved the final version the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Odero, J.O., Nambunga, I.H., Wangrawa, D.W. et al. Advances in the genetic characterization of the malaria vector, Anopheles funestus, and implications for improved surveillance and control. Malar J 22, 230 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04662-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04662-8