Abstract

Background

Cross-sectional surveys of chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) communities across sub-Saharan Africa show large geographical variation in malaria parasite (Plasmodium spp.) prevalence. The drivers leading to this apparent spatial heterogeneity may also be temporally dynamic but data on prevalence variation over time are missing for wild great apes. This study aims to fill this fundamental gap.

Methods

Some 681 faecal samples were collected from 48 individuals of a group of habituated chimpanzees (Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire) across four non-consecutive sampling periods between 2005 and 2015.

Results

Overall, 89 samples (13%) were PCR-positive for malaria parasite DNA. The proportion of positive samples ranged from 0 to 43% per month and 4 to 27% per sampling period. Generalized Linear Mixed Models detected significant seasonal and inter-annual variation, with seasonal increases during the wet seasons and apparently stochastic inter-annual variation. Younger individuals were also significantly more likely to test positive.

Conclusions

These results highlight strong temporal fluctuations of malaria parasite detection rates in wild chimpanzees. They suggest that the identification of other drivers of malaria parasite prevalence will require longitudinal approaches and caution against purely cross-sectional studies, which may oversimplify the dynamics of this host-parasite system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

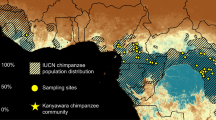

Six malaria parasite species (Plasmodium spp.) have been shown to infect wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): Plasmodium reichenowi, Plasmodium gaboni and Plasmodium billcollinsi (subgenus Laverania), and the less common Plasmodium vivax-like, Plasmodium ovale-like and Plasmodium malariae-like parasites [1]. Another Laverania species of chimpanzee malaria parasites, Plasmodium billbrayi, is recognized by some, but not all, authors [1, 2]. The distribution, diversity and phylogenetic relationships of Plasmodium spp. have been the focus of several extensive studies conducted in the sub-Saharan African range of chimpanzees [1,2,3,4,5]. Although these studies did not aim at producing directly comparable prevalence estimates, the resulting picture was one of extreme geographic variations, with values ranging from 0% in Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii (Issa Valley, Tanzania) [5] up to 48% in Pan troglodytes troglodytes across multiple sites [6]. This spatial heterogeneity may be explained by a complex combination of ecological factors influencing malaria parasite transmission, including the availability and abundance of vectors and/or the demographic, social, and behavioural characteristics of chimpanzee communities [5, 7].

However, before the effect of such factors can be explored, clarifying temporal variation in Plasmodium spp. prevalence in chimpanzees is necessary. For humans, as well as birds (the key wildlife model in malaria research), longitudinal studies have shown that malaria parasite prevalence often varies significantly between seasons and years [8, 9]. Such unaccounted-for temporal variation may influence the apparent geographic distribution of chimpanzee malaria parasites (mainly deduced from cross-sectional sampling), complicating the identification of local drivers of transmission [5,6,7, 10]. This study aimed at filling a fundamental gap in the understanding of the basic epidemiology of malaria parasites in chimpanzees by determining whether Plasmodium spp. detection rate varied in a wild human-habituated community across four non-consecutive sampling periods.

Methods

Study site and sample collection

Faecal samples were collected from known individuals of one habituated chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus) community at Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire. The site experiences two annual wet (minor: September–October; major: March–June) and dry seasons (minor: July–August; major: November–February), with an annual average rainfall of 1800 mm and temperatures between 24 and 30 °C. In this study, 681 samples collected between 2005 and 2015 from 19 males and 29 females aged 1–52 years old were included. Samples were selected across four non-consecutive sampling periods (1: 2005–2006; 2: 2009; 3: 2011–2012; 4: 2014–2015). On average, 14.2 samples were selected per individual (range 3–37). As pregnancy correlates with increased Plasmodium spp. detection, known pregnant individuals were excluded [11]. Group size varied from 22 to 40. Samples were stored in liquid nitrogen within 12 h after collection, then shipped and stored in Germany at − 80 °C.

Molecular analysis

DNA extracted from pea-sized faecal samples was tested for malaria parasites following a two-step screening process. First, samples were screened with a nested qPCR targeting a 90-bp fragment of a non-coding region of parasite mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)—first round primers qPlasm1f 5′-CTGACTTCCTGGCTAAACTTCC-3′ and qPlasm1r 5′-CATGTGATCTAATTACAGAAYAGGA-3′ and second round primers qPlasm2f 5′-AGAAAACCGTCTATATTCATGTTTG-3′ and qPlasm2r 5′-ATAGACCGAACCTTGGACTC-3′ [11, 12]. Positive samples were then additionally screened using a semi-nested PCR targeting a longer 350-bp fragment of mtDNA that comprised the 3′ end of cytochrome oxidase 1 gene, a short intergenic region and the 5′ end of the cytochrome b gene—first round primers Plasmseq 1f 5′-GGATTTAATGTAATGCCTAGACGTA-3′ and Plasmseq 1r 5′-ATCTAAAACACCATCCACTCCAT-3′ and second round primers Pspcytbf1 5′-TGCCTAGACGTATTCCTGATTATCCAG-3′ and Plasmseq 1r [11, 12]. These PCR systems were previously shown to amplify DNA from a broad range of parasites belonging to the genera Plasmodium and Hepatocystis [11, 12]. As chimpanzees hunt, detection of prey infectious agents may result in false positives [13]. Therefore, samples without chimpanzee-specific parasite sequences (N = 24) were additionally tested for the chimpanzee’s main prey, colobines, targeting a 122-bp fragment of mitochondrial 12S ribosomal RNA gene (12S) [13]. If positive for colobines, samples (N = 5) were excluded from analyses as parasite origin was ambiguous. PCR products were sequenced on both strands via Sanger’s methodology and analysed using GENEIOUS v.10 [14]. Sequences were compared with publically available sequences using BLAST [15]. Samples were considered positive if: a) chimpanzee-specific parasite sequences were obtained from semi-nested PCR products (N = 70); or, b) samples were tested negative for colobines and a PCR product was obtained with the semi-nested PCR but the sequencing failed (N = 17) or sequence assignment was unspecific, e.g., Plasmodium sp. (N = 2) [11].

Statistical analyses

To determine factors possibly affecting Plasmodium spp. detection in faeces, a Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) [16, 17] was fitted in R (R script available on request) [18] using R package lme4 (v.1.1.12, function glmer with a binomial error structure and logit link function [16, 19]). The full model included sex, age, (Julian) collection date, collection time, and sampling period as fixed effects. As the site experiences two wet and dry seasons per year, collection date (Julian date) expressed in radians was multiplied by two and the sine and cosine of it included (‘seasonality’) in the full model as additional fixed effects [20]. Individual was included as a random effect with age, collection date, collection time, and seasonality included as random slopes [21]. Age, collection date and collection time were z-transformed to mean of zero and standard deviation of one. To determine the combined significance of sex, age, sampling period, collection date, and seasonality, the full model was compared to a null model [22] lacking these fixed effects, but including all other terms using a likelihood ratio test (R-function anova with argument ‘test’ set as ‘Chisq’). Significance of each individual fixed effect was determined by comparing the full model with one lacking the respective fixed effect using a likelihood ratio test (R-function drop1 [22]). To test for seasonality, a reduced model without seasonality was compared to the full model using a likelihood ratio test. Total sample size for this analysis was 638 samples from 48 individuals. Model stability (assessed by dropping individuals one at a time and comparing model results with those obtained for the full model) [23] was not an issue.

Results

Molecular analysis

Overall, 89 samples (13%) were positive, with proportions of positive samples ranging from 0 to 43% per month and 4 to 27% per sampling period (Fig. 1). Sequences were obtained for 70 samples (79%). Plasmodium spp. sequences in this study exhibited 97–100% sequence identity to published sequences. The dominant Plasmodium spp. was P. gaboni (N = 47; 67.1%), followed by P. billcollinsi (N = 11; 15.7%), P. reichenowi (N = 6; 8.6%), P. vivax-like (N = 4; 5.7%), and P. malariae-like (N = 1; 1.4%). A single mixed infection (P. gaboni and P. reichenowi; 1.4%) was detected. During the study, 27 individuals (56%) were positive at least once (range: 1–9 positive samples per individual). In 16 of the 17 individuals who tested positive more than once different malaria parasite species were detected.

Temporal variation of malaria parasite faecal detection rate in chimpanzees. Circles represent monthly detection rates (with their 95% confidence intervals); circle area is proportional to the number of samples collected that month (range 1–85). The dotted line represents the model result regarding seasonal variation in detection rate

Statistical analyses

The full model was clearly significant when compared to the null model (likelihood ratio test: χ2 = 65.997, df = 8, P < 0.001), specifically showing age and sampling period as significant predictors (Table 1). A decrease in detection probability was observed with increasing age (estimate + SE = − 0.691 + 0.249, χ2 = − 2.775, df = 1, P = 0.004). Seasonality (comparison of full and reduced model: χ2 = 9.240, df = 2, P = 0.010) was significant (Table 1) with peaks during June and December and lows during March and September (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Marked, apparently stochastic variations in detection rates were observed at different temporal scales: monthly detection rates varied from 0 to 43%, whereas detection rates per sampling period varied from 4 to 27%. Strikingly, focusing on results of 2015 (N = 131) would have led to the erroneous conclusion that this chimpanzee community is malaria-free.

While shown for the first time in chimpanzees, such variations are not without precedent. Longitudinal studies of other host populations (e.g., humans, birds and lizards) showed both high seasonal and inter-annual variation, sometimes providing evidence for cyclical patterns with periods of 1–13 years [8, 9, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. In particular, large complex geographical variation in short and long-term patterns of Plasmodium falciparum has been observed worldwide [8]. For example, rates of malaria cases in Venezuela exhibited multi-annual cycles of 2–6 years, with higher rates directly following an El Niño event and increased rainfall [31]. Similarly, in Western Kenya, multi-annual malaria outbreak cycles of 2–4 years are associated with rainfall [24]. Such climatic factors are probably the strongest drivers behind prevalence patterns, having direct effects on vector abundance and parasite development and exhibiting high temporal fluidity [8, 9, 24, 28]. However, biotic factors most certainly also play a role, modifying the biology and behaviour of host, vector and/or parasite, and possibly operate at different temporal scales [7, 8, 24]. For example, changing host demographics with the influx of naïve and highly susceptible individuals can alter the pool of infective individuals, driving variability through changing processes of transmission and immunity within a population [24, 26, 31, 32]. The interplay between climatic and biotic factors therefore creates a spatiotemporally dynamic host-parasite system [8, 24].

Within a year, detection rates followed seasonal patterns: peaking 3 months after the start of the wet seasons and reaching their lowest levels at the end of dry seasons or beginning of wet seasons. Such seasonal increases in prevalence have been observed for most malaria parasites, including the closest relative of the chimpanzee-adapted Laveranian parasites, P. falciparum (the dominant cause of malaria-induced mortality in humans) [8]. In Bangladesh, both P. falciparum and P. vivax exhibited seasonal patterns associated with temperature and monthly rainfall [28]. This may be explained by higher abundance of vectors and/or higher prevalence of the parasites in vectors during rainy periods [8, 9, 24, 25]. The combination of stochastic and seasonal variation in detection rate, and presumably prevalence [8, 9, 27], has immediate practical consequences. These results caution against purely cross-sectional comparisons of detection rates across sites/habitat, which may over- or underestimate the abundance of parasites and oversimplify the dynamics of this host-parasite system.

Temporal variation also highlights the complexity of malaria parasite epidemiology in wild chimpanzee communities. This is partly due to the inherently complicated parasite life cycle and further complicated by fluctuating chimpanzee demography, community structure and behaviour [7]. For example, since younger individuals, and in particular infants and juveniles (under 4 and 10 years old, respectively), are more likely to be infected (this study and [5, 12]), changing group size and composition may alter infection patterns. As processes ultimately leading to the observed prevalence patterns are heterogeneous, future studies aimed at disentangling which of these factors determine the spatiotemporal distribution of malaria parasites in chimpanzees will require longitudinal sampling of a wide range of data on hosts, habitats, vectors, and parasite lineages [7,8,9, 27].

Conclusions

This study shows strong temporal fluctuations of malaria parasite prevalence in wild chimpanzees. These findings call for longitudinal approaches to further characterize this host-parasite system and contribute to stress the resemblance with the human-P. falciparum system.

References

Liu W, Sundararaman SA, Loy DE, Learn GH, Li Y, Plenderleith LJ, et al. Multigenomic delineation of Plasmodium species of the Laverania subgenus infecting wild-living chimpanzees and gorillas. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8:1929–39.

Krief S, Escalante A, Pacheco M, Mugisha L, André C, Halbwax M, et al. On the diversity of malaria parasites in African apes and the origin of Plasmodium falciparum from Bonobos. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000765.

Prugnolle F, Durand P, Neel C, Ollomo B, Ayala F, Arnathau C, et al. African great apes are natural hosts of multiple related malaria species, including Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1458–63.

Boundenga L, Ollomo B, Rougeron V, Mouele L, Mve-Ondo B, Delicat-Loembet L, et al. Diversity of malaria parasites in great apes in Gabon. Malar J. 2015;14:111.

Mapua MI, Petrželková KJ, Burgunder J, Dadáková E, Brožová K, Hrazdilová K, et al. A comparative molecular survey of malaria prevalence among Eastern chimpanzee populations in Issa Valley (Tanzania) and Kalinzu (Uganda). Malar J. 2016;15:423.

Liu W, Li Y, Learn GH, Rudicell RS, Robertson JD, Keele BF, et al. Origin of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in gorillas. Nature. 2010;476:420–5.

De Nys HM, Löhrich T, Wu D, Calvignac-Spencer S, Leendertz FH. Wild African great apes as natural hosts of malaria parasites: current knowledge and research perspectives. Primate Biol. 2017;4:47–59.

Reiner RC, Geary M, Atkinson PM, Smith DL, Gething PW. Seasonality of Plasmodium falciparum transmission: a systematic review. Malar J. 2015;14:343.

LaPointe DA, Atkinson CT, Samuel MD. Ecology and conservation biology of avian malaria. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2012;1249:211–26.

Kaiser M, Löwa A, Ulrich M, Ellerbrok H, Goffe AS, Blasse A, et al. Wild chimpanzees infected with 5 Plasmodium species. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1956–9.

De Nys HM, Calvignac-Spencer S, Boesch C, Dorny P, Wittig RM, Mundry R, et al. Malaria parasite detection increases during pregnancy in wild chimpanzees. Malar J. 2014;13:413.

De Nys HM, Calvignac-Spencer S, Thiesen U, Boesch C, Wittig RM, Mundry R, et al. Age-related effects on malaria parasite infection in wild chimpanzees. Biol Lett. 2013;9:20121160.

De Nys HM, Madinda NF, Merkel K, Robbins M, Boesch C, Leendertz FH, et al. A cautionary note on fecal sampling and molecular epidemiology in predatory wild great apes. Am J Primatol. 2015;77:833–40.

Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extended desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–9.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10.

McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized linear models. 2nd ed. London: Chapman and Hall; 1989.

Baayen RH. Analyzing Linguistic Data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

R CoreTeam. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016.

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48.

Stolwijk AM, Straatman H, Zielhuis GA. Studying seasonality by using sine and cosine functions in regression analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:235–8.

Barr DJ, Levy R, Scheepers C, Tily HJ. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: keep it maximal. J Memory Lang. 2013;68:255–78.

Forstmeier W, Schielzeth H. Cryptic multiple hypotheses testing in linear models: overestimated effect sizes and the winner’s curse. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2011;65:47–55.

Field A. Discovering Statistics using SPSS. London: Sage Publications; 2005.

Pascual M, Cazelles B, Bouma MJ, Chaves LF, Koelle K. Shifting patterns: malaria dynamics and rainfall variability in an African highland. Proc Biol Sci. 2008;275:123–32.

Baidjoe AY, Stevenson J, Knight P, Stone W, Stresman G, Osoti V, et al. Factors associated with high heterogeneity of malaria at fine spatial scale in Western Kenyan highlands. Malar J. 2016;15:307.

Lachish S, Knowles SC, Alves R, Wood MJ, Sheldon BC. Infection dynamics of endemic malaria in a wild bird population: parasite species-dependent drivers of spatial and temporal variation in transmission rates. J Anim Ecol. 2011;80:1207–16.

Schall JJ, Marghoob AB. Prevalence of a malarial parasite over time and space: Plasmodium mexicanum in its vertebrate host, the western fence lizard Sceloporus occidentalis. J Anim Ecol. 1995;64:177–85.

Reid H, Haque U, Roy S, Islam N, Clements A. Characterizing the spatial and temporal variation of malaria incidence in Bangladesh, 2007. Malar J. 2012;11:170.

Bensch S, Waldenström J, Jonzén N, Westerdahl H, Hansson B, Sejberg D, et al. Temporal dynamics and diversity of avian malaria parasites in a single host species. J Anim Ecol. 2007;76:112–22.

Lalubin F, Delédevant A, Glaizot O, Christe P. Temporal changes in mosquito abundance (Culex pipiens), avian malaria prevalence and lineage composition. Parasite Vectors. 2013;6:307.

Grillet M-E, Souki ME, Laguna F, León JR. The periodicity of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum in Venezuela. Acta Trop. 2014;129:52–60.

Baum E, Sattabongkot J, Sirichaisintho J, Kiattibutr K, Jain A, Taghavian O, et al. Common asymptomatic and submicroscopic malaria infections in Western Thailand revealed in longitudinal molecular and serological studies: a challenge to malaria elimination. Malar J. 2016;15:333.

Authors’ contributions

DFW participated in study design, laboratory work and data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. TL collected samples and participated in laboratory work. AS participated in laboratory work. RM participated in data analysis and writing of the manuscript. RMW participated in study design. SC-S participated in study design and writing of the manuscript. TD participated in study design. FHL designed and supervised the study and participated in writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Ministry of Research, Taï National Park, Office Ivoirien des Parcs et Réserves, and Centre Suisse de Recherche Scientifique en Côte d‘Ivoire for their logistical support. We also thank the Taї Chimpanzee Project field assistants and veterinarians, and especially Dr Hélène M De Nys, for their help in the field. Finally, we thank Marina Reus, Frauke Olthoff, Dr Paolo Gratton, and Colleen Stephens for their technical support.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request with the sequences generated in this study deposited in GenBank (Accessions: MF120373–MF120407, MF148905–MF148907).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study made use of non-invasive samples.

Funding

This research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and conducted as part of the research group Sociality and Health in Primates (FOR2136, LE1813/10-1).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, D.F., Löhrich, T., Sachse, A. et al. Seasonal and inter-annual variation of malaria parasite detection in wild chimpanzees. Malar J 17, 38 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2187-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2187-7