Abstract

Background

The impact of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP) used as intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp-SP) on mutant parasite selection has been poorly documented in Burkina Faso. This study sought first to explore the relationship between IPTp-SP and the presence of mutant parasites. Second, to assess the relationship between the mutant parasites and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Methods

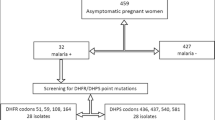

From September to December 2010, dried blood spots (DBS) were collected during antenatal care visits and at delivery from 109 pregnant women with microscopically confirmed falciparum malaria infection. DBS were analysed by PCR–restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP) for the polymorphisms at codons 51, 59, 108, and 164 of the Pfdhfr gene and codons 437 and 540 in the Pfdhps gene.

Results

Both the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes were successfully genotyped in 92.7% (101/109) of the samples. The prevalence of Pfdhfr mutations N51I, C59R and S108N was 71.3, 42.6 and 64.4%, respectively. Overall, 80.2% (81/101) of samples carried the Pfdhps A437G mutation. None of the samples had the Pfdhfr I164L and the Pfdhps K540E mutations. The prevalence of the triple mutation N51I + C59R + S108N was 25.7% (26/101). The use of IPTp-SP was associated with a threefold increased odds of Pfdhfr C59R mutation [crude OR 3.29; 95% CI (1.44–7.50)]. Pregnant women with recent uptake of IPTp-SP were at higher odds of both the Pfdhfr C59R mutation [adjusted OR 4.26; 95% CI (1.64–11.07)] and the Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high resistance, i.e., ≥ 2 Pfdhfr mutations [adjusted OR 3.45; 95% CI (1.18–10.07)]. There was no statistically significant association between the presence of the Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high resistance and parasite densities or both maternal haemoglobin level and anaemia.

Conclusion

The data indicate that despite the possibility that IPTp-SP contributes to the selection of resistant parasites, it did not potentiate pregnancy-associated malaria morbidity, suggesting the continuation of SP use as IPTp in Burkina Faso.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria during pregnancy persists as a major public health challenge with adverse consequences for mother and developing fetus [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended since 2004 relevant strategies, such as the administration of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine during pregnancy (IPTp-SP), the use of insecticide-treated nets and the effective management of clinical cases to reduce the burden of malaria and improve pregnancy outcomes [2]. Current policy dictates that SP should be provided to mothers at each scheduled focused antenatal care (ANC) visit in the second and third trimesters [3]. Although IPTp-SP has shown considerable benefits to mother and fetus [4], the emergence of Plasmodium falciparum resistance to SP can jeopardize this strategy [5].

SP resistance is linked to point mutations in the parasite genome, specifically the P. falciparum dihydrofolate reductase (Pfdhfr) and dihydropteroate synthetase (Pfdhps) genes [6, 7]. Mutations in Pfdhfr confer resistance to pyrimethamine while mutations in Pfdhps confer resistance to sulfadoxine and other sulfa drugs [8]. The more the mutations, the stronger the resistance. The Pfdhfr triple mutant (N51I + C59R + S108N) and Pfdhps double mutant (A437G + K540E) have been strongly associated with potential resistance in sub-Saharan Africa [9–12].

The impact of IPTp-SP on selection for drug-resistant parasites in the field is not well understood due to reported contradictory results. Indeed, although IPTp-SP has been associated with the selection of mutations [10, 13–15], it has been shown that self-reported use of IPTp-SP did not increase the prevalence of resistant alleles [5, 16]. Moreover, conflicting results about the impact of mutant parasites on pregnancy outcomes such as parasite densities, maternal haemoglobin level, and anaemia have been reported [14, 15].

In Burkina Faso, IPTp-SP was adopted in 2005 and resistance to SP in pregnant women has been only reported in rural areas [17, 18], and none of those studies had assessed the impact of SP on mutant parasites selection. Nevertheless, Coulibaly et al. [17] have shown that SP remained highly effective in Ziniaré, with a PCR corrected failure rate of only 1.3% at 42 days, and a PCR uncorrected failure rate of 6.5%. This study sought first, to explore the relationship between IPTp-SP and the presence of mutant parasites. Second, to assess the relationship between the mutant parasites and adverse pregnancy outcomes, including parasite densities, maternal haemoglobin level, and anaemia in Bobo-Dioulasso, the second largest city of the country.

Methods

Study area, subjects and sample collection

This study used archived samples collected from two malaria-in-pregnancy studies conducted in Bobo-Dioulasso from September to December 2010. The study protocol was approved by the National Ethics Committee for Health Research of Burkina Faso. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Details for these two cross-sectional studies including samples collection have been described elsewhere [19, 20]. Briefly, during these studies, all pregnant women presenting for routine ANC or delivery were consecutively recruited at the primary health facilities of Kua and Lafiabougou (both located in the peri-urban area of Bobo-Dioulasso). Sociodemographic data and information about the current and previous pregnancies were documented. Iron and folate supplementation and SP prophylaxis were given free of charge to all women attending ANC at both health facilities. The uptake of the drugs was recorded in their antenatal care files, and information on the use SP prophylaxis was obtained from the pregnant women through questionnaire and from these files.

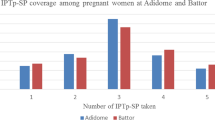

Based on these records, the women were classified as IPTp-SP+ if they took at least a first course of IPTp-SP and had correctly followed prophylaxis (Fig. 1), or IPTp-SP− group (control) if they had not received IPTp-SP since the beginning of their pregnancy. A finger-prick blood sample was collected from each participant for preparation of blood smears and blood spots on filter paper (Whatman grade 3). Maternal haemoglobin (Hb) concentration was measured using a haemoglobinometer (HemoCue AB, Angelhom, Sweden).

Laboratory procedures

Molecular genotyping was performed only on samples from women with a positive blood slide. All molecular tests were performed at the West African Centre for Cell Biology of Infectious Pathogens, Department of Biochemistry, Cell and Molecular Biology, University of Ghana, Accra.

Plasmodium falciparum DNA was extracted from dried blood spots using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit 50 (QIAgen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Eluted DNA was immediately used in amplification reactions or was stored at −20 °C until further processing.

SP resistance-mediating single nucleotide polymorphisms were analysed in both Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) followed by restriction enzyme digestion as previously described [21]. Polymorphisms investigated were as follows: N51I, C59R, S108N, and I164L for Pfdhfr gene and A437G and K540E for Pfdhps gene. Nested PCR products were resolved by 2.5% gel electrophoresis and results classified as wild type, pure mutant, and mixed infection (presence of both wild type and pure mutant in the same sample) on the basis of differential band sizes.

Definitions and statistical analyses

Data were double entered in Excel 2013 and analyses performed using STATA 12 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Mixed infection was considered as mutant. Infections were defined as intermediate-to-high resistance of Pfdhfr (≥2 Pfdhfr mutations) if Pfdhfr double and Pfdhfr triple mutations were detected [13]. Pregnant women were classified into primigravida (first-time mothers) and multigravida (those with at least one previous pregnancy). Age was stratified as ≤20 and >20 years. Recent IPTp-SP uptake was defined as receipt of the last SP dose within 2.5 months of blood sample collection, and early IPTp-SP uptake if the interval between last SP dose and the blood sample collection was >2.5 months. Anaemia was defined as an Hb level lower than 11.0 g/dL [13]. Parasite density values were log-transformed for statistical analyses.

Proportions for categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s Chi Square test. Comparisons of means between groups were done by the Student’s t test, while medians were compared by using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Logistic regression models were estimated to evaluate factors associated with the intermediate-to-high resistance of Pfdhfr and maternal anaemia. Linear regression models were used to assess predictors of log-transformed parasite densities and maternal Hb. Multivariable analyses were built using backward stepwise regression models, with an inclusion criterion of P value < 0.05 and exclusion criterion p value > 0.10. Statistical significance was set for a P value < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Maternal age, residence and education status were comparable between both IPTp-SP+ and IPTp-SP− groups. However, primigravida were more frequent in the IPTp-SP− group (P = 0.05) compared to the IPTp-SP+ group (Table 1). No statistically significant differences were found between the IPTp-SP groups in both maternal Hb levels and proportion with anaemia. However, the median parasite density in the IPTp-SP+ group (4080 parasites/μL) was higher than that in the IPTp-SP− group (2100 parasites/μL), although this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.06).

Relationship between IPTp-SP use and the prevalence of Pfdhfr and Pfdhps mutations

Overall 101 out of 109 parasite isolates (92.7%) were successfully genotyped for both Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes (Fig. 1). The prevalence of the Pfdhfr N51I, C59R and S108N mutations was 71.3, 42.6 and 64.4%, respectively. No mutation in the Pfdhfr gene at codon 164 was detected in any of the parasite isolates. Pregnant women who took the IPTp-SP had lower odds of the Pfdhfr N51I mutation compared to those who did not use any IPTp-SP [crude OR 0.24; 95% CI (0.09–0.62)]. The IPTp-SP+ group had greater than threefold increased odds of Pfdhfr C59R mutation compared to the IPTp-SP− group [crude OR 3.29; 95% CI (1.44–7.50)] (Table 2). In multivariable analysis, pregnant women with recent uptake of IPTp-SP were at higher odds of carrying the Pfdhfr C59R mutation compared to the early IPTp-SP group [adjusted OR 4.26; 95% CI (1.64–11.07)]. An additional table shows this in more detail (see Additional file 1: Table S1). Considering the Pfdhfr gene alone, the double mutation (including N51I + C59R, N51I + S108N or C59R + S108N) was the most prevalent combination, observed in 40.6% (41/101) of the isolates. The triple mutation N51I + C59R + S108N was found in 25.7% (26/101) of the isolates. The triple mutation was more predominant in the IPTp-SP+ group (32.6%) than in the IPTp-SP− group (19.2%), however the difference was not statistically different (P = 0.1). With regard to Pfdhps gene 80.2% (81/101) of samples carried the A437G mutation. The proportions of the A437G mutation in both IPTp-SP groups were statistically similar (P = 0.7). No Pfdhps K540E mutation was observed in any of the isolates tested.

Overall, 66.3% (67/101) of the isolates carried two or more Pfdhfr mutations, classified as the Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high resistance. The prevalence of infections with at least 2 Pfdhfr mutations was more predominant in the IPTp-SP+ group (71.4%) than in the IPTp-SP− group (61.5%), however the difference was not statistically different (P = 0.3) (Table 2). Nevertheless, further analysis showed that the uptake of one dose of IPTp-SP was significantly associated with the prevalence of infections with at least 2 Pfdhfr mutations [adjusted OR 5.34; 95% CI (1.10–26.40)]. An additional table shows this in more detail (see Additional file 2: Table S2). In addition, in multivariable logistic regression, pregnant women with recent uptake of IPTp-SP were at higher odds of the Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high resistance compared to those who did not use any IPTp-SP [adjusted OR 3.45; 95% CI (1.18–10.07)] (Table 3). Early receipt of IPTp-SP had lower odds of the Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high resistance compared to those who did not use any IPTp-SP [adjusted OR 0.61; 95% CI (0.20–1.86)] although this association did not reach statistical significance.

Effect of the Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high resistance on maternal outcomes

There was no statistically significant association between the presence of the Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high resistance and parasite densities, maternal Hb level and prevalence of maternal anaemia (Tables 4, 5). However, significant predictors for high parasite densities included primigravidae and early IPTp-SP receipt (Table 4). Furthermore, living in the area of the primary health centre of Kua resulted in a significant increase of 0.90 g/dL in the maternal Hb level [adjusted regression coefficient = 0.90; 95% CI (0.24–1.55)] (Table 4) and a lower odds of anaemia [adjusted OR 0.35; 95% CI (0.14–0.84)] (Table 5).

Discussion

This study analysed samples collected 5 years after adoption of IPTp-SP in Burkina Faso. The prevalence of Pfdhfr triple mutation N51I + C59R + S108N in the present study (25.7%) was low compared to the rates of 44.9 and 50% reported in pregnant women at the same period in Ziniaré [17] and in the general population [22], respectively. However, Tahita et al. [18] reported a lower prevalence of 11.4% in pregnant women during the same period in Nanoro, a small town in Burkina Faso. Those studies had been carried out in rural settings where malaria transmission is high and seasonal, mainly occurring during the months of August–December [17, 18, 22]. In Burkina Faso, SP had been used as second-line treatment before 2005, but was increasingly used as a first-line drug after chloroquine was discontinued in 2005, when artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) was not yet readily available [23, 24]. Therefore, those different reports suggest either a variation in SP pressure according to study areas or differing access to ACT [18]. The prevalence of Pfdhfr triple mutation reported in this study was also lower than those previously reported during pregnancy in other African countries where the proportion of Pfdhfr triple mutation ranged from 36 to 75% [5, 8, 13, 14, 16, 25]. The Pfdhps A437G mutation is very common across Africa [16, 26] and its prevalence in this study (80.2%) was higher than the reported rates (34.2–75.3%) in other studies conducted during the same period in pregnant women from Burkina Faso [17, 18]. This difference could be attributed to a variation in the level of SP use in different parts of the country, and the effect of widespread use of an antibiotic drug, namely cotrimoxazole in the population [27]. Indeed, this mutation is involved in resistance to sulfadoxine in endemic areas and its selection by SP in pregnant women has been recently shown in Cameroon [26]. Both the Pfdhfr I164L and the Pfdhps K540E mutations were not detected in the present study, suggesting that these are still absent in Burkina Faso. This is consistent with previous reports in the country [17, 18, 22, 23, 28, 29] as well as in other settings in West Africa [8, 13, 14, 25]. However, a low proportion of Pfdhps K540E mutation (0.37%) has been recently reported in Mali [17].

In accordance with previous reports from Ghana [13] and Mali [30], this study showed that the Pfdhfr N51I mutation was not selected by the use of IPTp-SP. However, the use of IPTp-SP was associated with an increased prevalence of the Pfdhfr C59R mutation. Significantly, IPTp-SP was associated with an increased prevalence of both the Pfdhfr C59R mutation and Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high resistance when SP was expected to be present in peripheral blood, i.e., if the last IPTp-SP dose was taken within 2.5 months before the blood collection. Furthermore, among pregnant women who benefited from one dose of IPTp-SP, more than 70% of them had used IPTp-SP recently. This is a plausible explanation of the association between the uptake of one dose of IPTp-SP and the prevalence of infections with at least 2 Pfdhfr mutations. This is the first study directly implicating the recent use of IPTp-SP in the selection of drug resistant parasite mutants in pregnant women from Burkina Faso. The findings from this study are consistent with those from previous studies carried out in Mozambique [10] and in Tanzania [15], where it was shown that recent receipt of SP was associated with greater prevalence of resistant parasites. This suggests that these resistant parasites are no longer competitive during re-infection with other strains and that resistance decreases when active drug pressure decreases [10, 31]. Several observational studies in Africa had shown the association between the use of IPTp-SP and the increased prevalence of mutations [13, 14, 26, 32]. However, those studies did not use the timing between the last dose of IPTp-SP and the blood sample collection as a proxy to further assess this association.

Higher parasite densities were frequent in pregnant women with early receipt of IPTp-SP compared to those who did not use any IPTp-SP. After stratification by the presence of Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high resistance, this association was statistically significant in primigravida who harboured parasites with low Pfdhfr grade of resistance. This is not surprising because parasite densities decrease due to acquired immunity against malaria parasites when parity increases [13]. The use of IPTp-SP was not associated with higher parasite densities in Mozambique [10] and in Malawi [11], despite the possibility that IPTp-SP contributes to the selection of quintuple mutant-resistant parasites. Those findings contrast with a report from Tanzania where recent receipt of SP was associated with higher parasite densities due to the presence of Pfdhps mutation at codon 581 in that study [15].

This study showed that the Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high resistance was not associated with maternal anaemia and maternal Hb level. This is consistent with previous reports from Mozambique and Malawi [10, 11]. A plausible explanation is the lack of an effect of the mutations on parasite densities [10]. Nevertheless, living in the area of the primary health centre of Kua was a protecting factor against anaemia. Malarial anaemia is usually associated with more prolonged infections [33], therefore, it is likely that women living nearer to the health centre sought medical attention sooner and thus avoided the development of anaemia.

The limitations of this study include the small size of the studied population and the cross-sectional approach used. A longitudinal study would enable a better assessment of the impact of SP on the selection of mutant parasites by comparing the level of drug resistance before and after SP use.

Conclusion

The present study provides an update on the prevalence of mutations conferring SP resistance 5 years after the implementation of the IPTp-SP policy in Burkina Faso. SP given for IPTp selects for both Pfdhfr C59R mutation and Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high mutant parasites in maternal peripheral blood when SP is still present in blood. However Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high resistance is not associated with pregnancy-associated malaria morbidity. Altogether, the findings from this study suggest that SP may still be efficacious when used as IPTp. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to evaluate the in vitro and in vivo efficacy of SP.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

artemisinin combination therapy

- ANC:

-

antenatal clinic

- CI:

-

confident interval

- DBS:

-

dried blood spots

- Hb:

-

haemoglobin

- IPTp-SP:

-

intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine

- OR:

-

odd ratio

- Pfdhfr :

-

P. falciparum dihydrofolate reductase

- Pfdhps :

-

P. falciparum dihydropteroate synthetase

- RFLP:

-

restriction fragment length polymorphism

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Steketee RW, Nahlen BL, Parise ME, Menendez C. The burden of malaria in pregnancy in malaria-endemic areas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:28–35.

WHO. A strategic framework for malaria prevention and control during pregnancy in the African region. Brazzaville: World Health Organization, 2004. http//www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/afr_mal_04_01/en. Accessed 19 May 2016.

WHO. Updated WHO Policy Recommendation (October 2012): Intermittent Preventative Treatment of Malaria in Pregnancy Using Sulfadoxine–Pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP). Geneva: World Health Organization. http//www.who.int/malaria/iptp_sp_updated_policy_recommendation_en_102012.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2016.

Diakite OS, Kayentao K, Traoré BT, Djimde A, Traoré B, Diallo M, et al. Superiority of 3 over 2 doses of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine for the prevention of malaria during pregnancy in mali: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:215–23.

Mockenhaupt FP, Bedu-Addo G, Eggelte TA, Hommerich L, Holmberg V, von Oertzen C, et al. Rapid increase in the prevalence of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine resistance among Plasmodium falciparum isolated from pregnant women in Ghana. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1545–9.

Peterson D, Walliker D, Wellems T. Evidence that a point mutation in dihydrofolate reductase–thymidylate synthase confers resistance to pyrimethamine in falciparum malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9114–8.

Triglia T, Menting JG, Wilson C, Cowman AF. Mutations in dihydropteroate synthase are responsible for sulfone and sulfonamide resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13944–9.

Marks F, Evans J, Meyer CG, Browne EN, Flessner C, Von Kalckreuth V, et al. High prevalence of markers for sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum in the absence of drug pressure in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1101–5.

Iwalokun BA, Iwalokun SO, Adebodun V, Balogun M. Carriage of mutant dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase genes among Plasmodium falciparum isolates recovered from pregnant women with asymptomatic infection in Lagos, Nigeria. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24:436–43.

Menéndez C, Serra-Casas E, Scahill MD, Sanz S, Nhabomba A, Bardají A, et al. HIV and placental infection modulate the appearance of drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in pregnant women who receive intermittent preventive treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:41–8.

Taylor SM, Antonia AL, Chaluluka E, Mwapasa V, Feng G, Molyneux ME, et al. Antenatal receipt of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine does not exacerbate pregnancy-associated malaria despite the expansion of drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum: clinical outcomes from the QuEERPAM study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:42–50.

Siame MNP, Mharakurwa S, Chipeta J, Thuma P, Michelo C. High prevalence of dhfr and dhps molecular markers in Plasmodium falciparum in pregnant women of Nchelenge district, Northern Zambia. Malar J. 2015;14:190.

Mockenhaupt FP, Eggelte TA, Tamara B, Thompson WNA, Bienzle U. Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase alleles and pyrimethamine use in pregnant ghanaian women. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:21–6.

Mockenhaupt FP, Bedu-Addo G, Junge C, Hommerich L, Eggelte TA, Bienzle U. Markers of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in placenta and circulation of pregnant women. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:332–4.

Harrington WE, Mutabingwa TK, Muehlenbachs A, Sorensen B, Bolla MC, Fried M, et al. Competitive facilitation of drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites in pregnant women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9027–32.

Bouyou-Akotet MK, Mawili-Mboumba DP, Tchantchou TDD, Kombila M. High prevalence of sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine-resistant alleles of Plasmodium falciparum isolates in pregnant women at the time of introduction of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine in Gabon. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:438–41.

Coulibaly SO, Kayentao K, Taylor S, Guirou EA, Khairallah C, Guindo N, et al. Parasite clearance following treatment with sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine for intermittent preventive treatment in Burkina-Faso and Mali: 42-day in vivo follow-up study. Malar J. 2014;13:41.

Tahita MC, Tinto H, Erhart A, Kazienga A, Fitzhenry R, VanOvermeir C, et al. Prevalence of the dhfr and dhps mutations among pregnant women in Rural Burkina Faso five years after the introduction of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0137440.

Cisse M, Sangare I, Lougue G, Bamba S, Bayane D, Guiguemde RT. Prevalence and risk factors for Plasmodium falciparum malaria in pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Bobo-Dioulasso (Burkina Faso). BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:631.

Cisse M, Diallo AH, Somé DA, Poda A, Awandare AG, Guiguemdé TR. Association of placental Plasmodium falciparum parasitaemia with maternal and newborn outcomes in the periurban area of Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Parasitol Open. 2016;2:e15.

Jonathan V, Sunil P, Chris D, Grant D, Daniel K, Sam N, et al. Protocols for detecting mutations conferring resistance to the antifolate class of antimalarial drugs: DHFR Ile-51, Arg-59, Asn-108, Leu-164, and DHPS Gly-437, Glu-540: April, 2004. http://www.muucsf.org/protocols/pdf/Molecular markers of antifolate resistance (dhfr, dhps).pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2013.

Geiger C, Compaore G, Coulibaly B, Sie A, Dittmer M, Sanchez C, et al. Substantial increase in mutations in the genes pfdhfr and pfdhps puts sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine-based intermittent preventive treatment for malaria at risk in Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19:690–7.

Tinto H, Ouédraogo JB, Zongo I, van Overmeir C, van Marck E, Guiguemdé TR, et al. Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine efficacy and selection of Plasmodium falciparum DHFR mutations in Burkina Faso before its introduction as intermittent preventive treatment for pregnant women. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:608–13.

Tipke M, Diallo S, Coulibaly B, Störzinger D, Hoppe-Tichy T, Sie A, et al. Substandard antimalarial drugs in Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2008;7:95.

Bertin G, Briand V, Bonaventure D, Carrieu A, Massougbodji A, Cot M, et al. Molecular markers of resistance to sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine during intermittent preventive treatment of pregnant women in Benin. Malar J. 2011;10:196.

Chauvin P, Menard S, Iriart X, Nsango SE, Tchioffo MT, Abate L, et al. Prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum parasites resistant to sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine in pregnant women in Yaoundé, Cameroon: emergence of highly resistant pfdhfr/pfdhps alleles. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2566–71.

Diallo DA, Sutherland C, Nebié I, Konaté AT, Ord R, Pota H, et al. Sustained use of insecticide-treated curtains is not associated with greater circulation of drug-resistant malaria parasites, or with higher risk of treatment failure among children with uncomplicated malaria in Burkina Faso. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:237–44.

Dokomajilar C, Lankoande ZM, Dorsey G, Zongo I, Ouedraogo J-B, Rosenthal PJ. Roles of specific Plasmodium falciparum mutations in resistance to amodiaquine and sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine in Burkina Faso. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:162–5.

Somé AF, Séré YY, Dokomajilar C, Zongo I, Rouamba N, Greenhouse B, et al. Selection of known Plasmodium falciparum resistance-mediating polymorphisms by artemether–lumefantrine and amodiaquine-sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine but not dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine in Burkina Faso. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1949–54.

Diourté Y, Djimdé A, Doumbo OK, Sagara I, Coulibaly Y, Dicko A, et al. Pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine efficacy and selection for mutations in Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase in Mali. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:475–8.

Hastings I, Donnelly M. The impact of antimalarial drug resistance mutations on parasite fitness, and its implications for the evolution of resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2005;8:43–50.

Iriemenam NC, Shah M, Gatei W, van Eijk AM, Ayisi J, Kariuki S, et al. Temporal trends of sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP) drug-resistance molecular markers in Plasmodium falciparum parasites from pregnant women in western Kenya. Malar J. 2012;11:134.

Ochiel DO, Awandare GA, Keller CC, Hittner JB, Kremsner PG, Weinberg JBPD. Differential regulation of beta-chemokines in children with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4190–7.

Authors’ contributions

MC and RTG conceived of and designed the field study. MC conducted the field study. MC and AS conceived and designed the molecular analysis. AS with assistance from MC and GAA performed the molecular analysis. MC analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. GAA, AS, HT, MPH, and RTG critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to all midwives and pregnant women from both Kua and Lafiabougou health centres.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and approval from the National Ethics Committee for Health Research of Burkina Faso.

Consent for publication

This part is not applicable because the manuscript contains no individual person’s data in any form (including individual details, images or videos).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the National Ethics Committee for Health Research of Burkina Faso. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Funding

Part of this work was supported by funds from a World Bank African Centres of Excellence grant (ACE02-WACCBIP: GAA) and a Wellcome Trust DELTAS grant (107755/Z/15/Z: AGA). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

12936_2017_1695_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Table S1. Risk factors associated with the Pfdhfr C59R mutation. The data provided showed the association between time between last SP dose and the survey and the prevalence of Pfdhfr C59R mutation using a logistic regression model adjusted for residence, age, and gravidity.

12936_2017_1695_MOESM2_ESM.docx

Additional file 2: Table S2. Association between the number of SP doses and the Pfdhfr intermediate-to-high resistance. The data provided showed the association between the number of SP doses and the prevalence of at least 2 Pfdhfr mutations using a logistic regression model adjusted for residence, age, and gravidity.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Cisse, M., Awandare, G.A., Soulama, A. et al. Recent uptake of intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine is associated with increased prevalence of Pfdhfr mutations in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Malar J 16, 38 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1695-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1695-1