Abstract

Background

Resistance to sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) in Plasmodium falciparum parasites is associated with mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase (dhfr) and dihydropteroate synthase (dhps) genes and has spread worldwide. SP remains the recommended drug for intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in pregnancy (IPTp) and information on population prevalence of the SP resistance molecular markers in pregnant women is limited.

Methods

Temporal trends of SP resistance molecular markers were investigated in 489 parasite samples collected from pregnant women at delivery from three different observational studies between 1996 and 2009 in Kenya, where SP was adopted for both IPTp and case treatment policies in 1998. Using real-time polymerase chain reaction, pyrosequencing and direct sequencing, 10 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of SP resistance molecular markers were assayed.

Results

The prevalence of quintuple mutant (dhfr N51I/C59R/S108N and dhps A437G/K540E combined genotype) increased from 7 % in the first study (1996–2000) to 88 % in the third study (2008–2009). When further stratified by sample collection year and adoption of IPTp policy, the prevalence of the quintuple mutant increased from 2.4 % in 1998 to 44.4 % three years after IPTp policy adoption, seemingly in parallel with the increase in percentage of SP use in pregnancy. However, in the 1996–2000 study, more mutations in the combined dhfr/dhps genotype were associated with SP use during pregnancy only in univariable analysis and no associations were detected in the 2002–2008 and 2008–2009 studies. In addition, in the 2008–2009 study, 5.3 % of the parasite samples carried the dhps triple mutant (A437G/K540E/A581G). There were no differences in the prevalence of SP mutant genotypes between the parasite samples from HIV + and HIV- women over time and between paired peripheral and placental samples.

Conclusions

There was a significant increase in dhfr/dhps quintuple mutant and the emergence of new genotype containing dhps 581 in the parasites from pregnant women in western Kenya over 13 years. IPTp adoption and SP use in pregnancy only played a minor role in the increased drug-resistant parasites in the pregnant women over time. Most likely, other major factors, such as the high prevalence of resistant parasites selected by the use of SP for case management in large non-pregnant population, might have contributed to the temporally increased prevalence of SP resistant parasites in pregnant women. Further investigations are needed to determine the linkage between SP drug resistance markers and efficacy of IPTp-SP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria during pregnancy persists as a major public health challenge with adverse consequences for the pregnant woman and the developing foetus. About 50 million women living in malaria-endemic countries become pregnant each year [1]. In Africa, an estimated 30 million women are at risk of Plasmodium falciparum infection during pregnancy annually [2]. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and malaria have overlapping global distributions [3]. Currently, available interventions to prevent or mitigate the adverse effects of malaria during pregnancy include intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp), insecticide-treated bed-nets (ITNs), and case management. In sub-Saharan Africa, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the administration of at least two curative doses of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) for IPTp after the first trimester of pregnancy [4]. A recent study indicated that three doses of SP are required to provide adequate protection to pregnant women [5]. More SP doses are also recommended for women with HIV who are not taking daily cotrimoxazole (CTX, sulphamethoxazole-trimethoprim) for the prevention of opportunistic infections [4]. However, for HIV-infected women taking CTX, WHO does not recommend IPTp-SP, as CTX inhibits the same enzymes as SP in the folic acid biosynthetic pathway, presumably acting as an anti-malarial, and the excess of adverse events were observed in the SP and CTX co-medication [4].

In most African countries, SP remains the recommended drug for IPTp due to its safety profile, efficacy, cost effectiveness and easy administration through the existing health structures, such as antenatal clinics (ANC) [6, 7]. IPTp-SP has been shown to reduce the prevalence of placental malaria infection, maternal severe anaemia in primigravidae [8–12], preterm delivery [5, 13], infant low birth-weight [5, 13–15] and the neonatal mortality rate [16]. However, P. falciparum resistance to SP has emerged, originating at the Thailand-Cambodia border and then spreading rapidly to other Asian countries and subsequently to Africa [17]. Concurrently, cross-resistance has also developed between trimethoprim and pyrimethamine in P. falciparum malaria parasites [18]. Due to the increasing SP and existing high chloroquine resistance, WHO has recommended artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) as alternative first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria in most endemic countries. However, ACT is not recommended for prevention of malaria including in pregnant women due to the absence of adequate safety data [19].

Resistance to SP has been linked to point mutations in the parasite dihydrofolate reductase (dhfr) and dihydropteroate synthase (dhps) genes [20, 21]. Mutations in dhfr confer resistance to pyrimethamine, which occurs in a stepwise pattern [22], while mutations in dhps confer resistance to sulphadoxine and other sulpha drugs. In sub-Saharan Africa, the dhfr triple mutant (Asn-108/Ile-51/Arg-59) and dhps double mutant (Gly-437/Glu-540) have been strongly associated with resistance to SP while the Leu-164 mutation, a major contributor to the rapid spread of high level anti-folate resistance, has recently begun to emerge in Africa [23–25]. The dhps mutation at codon 581 is linked with a high rate of therapeutic failure and the emergence of the dhps triple mutant allele (A437G/K540E/A581G) has been confirmed in Tanzania [26], and the prevalence is increasing [27]. Recently, the dhps mutation at positions 581 and 613 were reported in Kenya [28]. Collectively, these data confirm that the quintuple mutant, comprised of the dhfr triple mutant (Asn-108/Ile-51/Arg-59) genotype and dhps double mutant (Gly-437/Glu-540) genotype, and other additional dhfr and dhps mutations are good predictors of SP treatment failure in children [25, 29–31].

The rapid spread of SP-resistant parasites associated with SP treatment failure in children [31] and paucity of scientific data linking SP resistant parasites and IPTp-SP efficacy in pregnant women [32] highlights the need for an evaluation of the prevalence of SP molecular markers in the context of IPTp-SP. Recently, studies conducted in Tanzania (data and samples from 2002–2005) showed that IPTp-SP was associated with an increased fraction of parasites carrying the resistant allele at dhps 581, an increased parasite density and intense placental inflammation [33], and further suggested that IPTp may not improve overall pregnancy outcomes [34]. However, IPTp-SP was effective in preventing placental malaria infection in several subsequent studies conducted in other African countries [5, 13, 35]. Another recent report showed that IPTp-SP increased the prevalence of dhfr/dhps quintuple mutant infection in HIV-infected pregnant women, but the women with drug-resistant parasites did not have increased malaria-related adverse clinical outcomes [36]. The results from these divergent studies suggest that although IPTp-SP could select resistant parasites, IPTp-SP remains beneficial in its protection against malaria infection in some African countries [5, 13, 35].

This study was conducted using the parasites from Kenyan pregnant women to (a) determine the temporal trends of SP resistance molecular markers over 13 years (between 1996 and 2009), (b) assess if there are any notable differences between peripheral and placental parasites in the profile of SP resistance molecular markers, and (c) examine the relationship between SP resistance molecular markers and IPTp adoption and use of SP during pregnancy, further stratified by HIV status. The study was conducted in the malaria endemic area of western Kenya where there is a high prevalence of HIV co-infection and IPTp-SP policy and SP treatment policy were both adopted in 1998.

Methods

Study sites and sample sources

This study used the samples collected from three separate hospital-based malaria in pregnancy studies conducted in Nyanza province, western Kenya between 1996 and 2009. Details for these three observational studies have been described elsewhere ([37, 38] and Ouma et al, manuscript in preparation). Briefly, between 1996 and 2000, a malaria in pregnancy study was conducted in Provincial General Hospital, Kisumu town to assess the effect of placental malaria on perinatal HIV infection. A second malaria in pregnancy immunological study designed to investigate cellular immune responses in pregnant women was carried out at the same hospital from 2002 to the middle of 2004 and then continued at Siaya District Hospital until 2008. A third malaria in pregnancy study was conducted between 2008 and 2009 in both Siaya and Bondo District Hospitals and the aim of this study was to assess the effectiveness of daily IPTp with SP or CTX prophylaxis in preventing placental malaria in pregnant women. Both Siaya and Bondo District Hospitals are located in rural areas around Kisumu town. Compared to Kisumu town, the rural areas have a relatively higher malaria transmission. The first two studies collected the history of self-reported SP use (case management or any dose of IPTp) during pregnancy while the 2008–2009 study obtained information for both IPTp-SP use and CTX use validated by antenatal clinic records. In Kenya, although the policy of IPTp-SP was adopted in 1998 and it remains till now as per Kenya Ministry of Health (MOH) guidelines, uptake was slow, evidenced by the study showing only 7 % of pregnant women received more than one dose of SP in western Kenya 4 years after the adoption of IPTp-SP policy [39]. Daily CTX prophylaxis for the prevention of opportunistic infections in pregnant women was officially recommended as one component of HIV care in 2005 and the distribution of free ITNs to pregnant women became part of antenatal care in early 2008. In addition, although the drug policy in Kenya shifted to SP from chloroquine in 1998 and then to Coartem® in 2004 for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria, as late as 2010, SP was still used to treat uncomplicated malaria in 37 % of households surveyed in Kisumu, compared to 32 % that used ACT [40]. The prevalence of the dhfr/dhps quintuple mutant in children from the same study area increased from 29 % in 1996 to 62 % and 85 % in 2001 and 2007, respectively [41].

For all three observational studies described above, samples were collected at delivery. The selection of samples from the three studies for the present investigation was based on the availability of samples in both HIV + and HIV- women rather than randomization of characteristics. In total, 489 peripheral samples from patients who were P. falciparum parasite positive at delivery were used for the study: 180 from 1996–2000, 176 from 2002–2008 and 133 from 2008–2009. In addition, among the 133 peripheral samples from the 2008–2009 period, 125 were paired with placental samples from the same woman.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Nairobi, Kenya, the University of Georgia, Athens, USA, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Laboratory procedures

DNA purification

Genomic DNA was purified from dried blood spots collected from the 2008–2009 period using the Chelex method [42] and also from frozen red blood cell pellets for the remaining samples by micro-centrifugation using a commercial DNA purification QIAamp® blood mini-kit (Qiagen Inc., CA, USA).

Single nucleotide polymorphisms genotyping

Ten single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at dhfr codons 50, 51, 59, 108 and 164, and dhps codons 436, 437, 540, 581 and 613 were typed using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), pyrosequencing and direct sequencing.

RT-PCR

RT-PCR (Stratagene Mx3005P, CA, USA) was used to detect SNPs at dhfr codons 51, 59, 108, 164 and dhps codons 437 and 540 for 2008–2009 samples using a published procedure [43]. Briefly, standards and field samples were run in duplicate in 25 μl reactions containing TaqMan Universal Mastermix (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA), 2 μl of DNA (diluted 1:10), gene-specific forward and reverse primers, and SNP-specific TaqMan MGB probes (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Four 10-fold serial dilutions of both wild type and mutant parasite laboratory strain standards, depending on the SNP, and negative control templates were run on every plate as positive and negative controls.

PCR for pyrosequencing and pyrosequencing reactions

The remaining SNPs for 2008–2009 samples and all the SNPs for 1996–2000 and 2002–2008 samples were assayed using a published pyrosequencing method [44]. All PCR primers and sequence primers were synthesized at the CDC Biotechnology Core Facility, Atlanta, USA and experiment conditions were followed based on the described procedures [44]. The following laboratory strains were used as controls for detecting wild and mutant strains: 3D7 (wild type) for dhfr 50, 51, 59, 108, 164 and dhps 436, 581, 613; Dd2 (mutant) for dhfr 50, 51, 59 and dhps 613; V1/S (mutant) for dhfr 108, 164 and dhps 613; FCR3 (wild type) for dhps 437; D6 (mutant) for dhps 436; 3D7 (mutant) for dhps 437; PS-FCR (wild type) and PS-PERU (mutant) for dhps 540; and K1 (mutant) for dhps 581. No DNA templates were included in all reactions as negative controls. The assays were performed on the PSQ 96 plate using PyroMark ID (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden) and the sample genotypes were determined using the PyroMark ID 1.0 SNP software (Biotage AB).

Direct sequencing

All moot results and new mutations were confirmed by direct sequencing. Dhfr and dhps fragments were amplified using nested PCR sequence protocols [45]. Sequencing of the nested purified PCR products were performed using Big Dye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit on iCycler thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). The reactions were precipitated in 70 % ethanol to clean up dye terminators, rehydrated in 10 ml HiDi formamide and then sequenced on a 3130 ABI Genetic Analyzer (ABI Prism, CA, USA).

Genotyping for multiplicity of infection

Size variant alleles of merozoite surface protein 1 (msp 1) and msp 2 were determined by nested PCR for the assessment of multiplicity of infection (MOI). The sequences of the oligonucleotide primers used for amplification of the genetic markers and experimental conditions were set based on the published and recommended methods [46, 47]. Positive and negative controls were included in each experiment. The nested PCR products were analysed by 3 % agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ultraviolet transilluminator after staining with ethidium bromide. The band sizes were estimated using the gel imaging system and the Labworks image acquisition and analysis software v4.6 (UVP BioImaging Systems, CA, USA).

Definitions

Drug-resistant markers

For all 10 SNPs genotyped, each was coded to designate pure (infection with only either wild type or mutant strains) or mixed (infection with both wild and mutant strains where the minor strain was >30 % of major). Mixed infection was considered as mutant. The SP genotypes (dhfr dhps and combined dhfr/dhps) were categorized based on the criteria of Kublin et al[29]. Dhfr genotype, based on mutations at codons 51, 59, and 108, was classified as wild type, single, double, and triple (pooled triple mixed and pure) while dhps genotype (mutations at codons 437 and 540) was classified as wild type, single, and double (pooled double mixed and pure). Combined dhfr and dhps genotypes (mutations at dhfr 51, 59, 108 + dhps 437, 540) were defined as wild type, single, double, triple, quadruple, quintuple (pooled quintuple mixed and pure). The quadruple mutants were categorised either as dhfr triple + dhps single or dhfr double + dhps double. The quintuple mutants, in either pure or mixed infection, represent infections in which all the five mutations were detected at codons 51, 59, 108, 437 and 540. Furthermore, additional combinations of dhps SNPs at codons 436, 437 and 540, at codons 437, 540 and 581, or at codons 436, 437, 540 and 581 were analysed to further evaluate the progression of dhps mutations. In this study, the prevalence of SNP mutations and genotypes were estimated [29].

Multiplicity of infection

MOI was assessed by using the polymorphic regions of P. falciparum msp 1 and msp 2 genes as markers. Since the size variant alleles of msp 2 was consistently more diverse than msp 1 in previous studies [46, 48] and in the current study, msp 2 was selected to evaluate MOI. Mean MOI was calculated as the total number of variant alleles (clones) divided by the number of positive samples for the marker gene msp 2. Mixed infection was defined as individual infection with more than one variant allele (clone).

Clinical

As there were differences in the collection of data for SP use in pregnancy for the three different observational studies, the common variable “SP use in pregnancy (yes or no)” was used which represented the history of self-reported SP use by either case management or any dose of IPTp-SP for first two study periods and validated IPTp-SP use for the third study period. Other variables used in analysis included adoption of IPTp policy (yes or no, policy adopted in 1998), Cotrimoxazole use (yes or no, data only collected in third study), maternal age, gravidity (categorized as primigravid, secundigravid, and multigravid), area of residence, haemoglobin level (g/dl) at delivery (<11 g/dl considered anaemic), peripheral and placental parasite density (parasites/μl) determined by standard microscopic examination of blood smears, and confirmed HIV status by standard laboratory serological tests using same algorithm.

Data and statistical analysis

The objectives of the present study were to determine the prevalence of SP molecular markers in the parasites from pregnant women over time from 1996 to 2009 and to explore potential epidemiological factors affecting the prevalence of SP resistance molecular markers in the pregnant women. Therefore, the analysis strategies included: 1) a descriptive analysis on temporal trend of drug resistant markers, mixed infection and MOI, and comparisons of these parameters between peripheral and placental samples and between HIV statuses of samples used, and 2) an association analysis between mutations in resistance genotypes as the outcome variables and use of SP in pregnancy as the primary exposure variable.

Characteristics of the study population from the three different studies were analysed by Pearson chi-square tests and ANOVA. Parasite density was log transformed prior to statistical analysis. Differences in the prevalence of SNP mutations, dhfr, dhps and the combined dhfr/dhps genotypes among the three studies and other subcomponent comparisons were examined by overall chi-square tests or exact chi-square tests for expected cell counts less than five, considering each molecular marker or genotype as independent. The details of the descriptive analysis are described in additional file [see Additional file 1].

To examine the relationship between SP use in pregnancy and dhfr, dhps, and combined dhfr/dhps genotypes, univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed. As the original study methodologies differed, data from the three studies were not pooled, but instead, analysed separately. In all epidemiological models, SP use in pregnancy was considered the primary exposure of interest and the (1) dhfr (N51I/C59R/S108N), (2) dhps (A437G/K540E), or (3) combined dhfr/dhps genotypes as three separate outcomes. The final most parsimonious multivariable model in each study was selected after an assessment of regression assumptions, interaction and confounding factors. No interaction terms were included in any final models as all possible two-way interaction terms with the primary exposure of interest were insignificant at the α = 0.05 significance level based on an overall likelihood ratio test. Confounding was assessed based on a +/− 10 % change in odds ratio (OR) estimate, biological plausibility and the results of univariable analysis. Placental parasite density and maternal age were excluded from the final models due to co-linearity with peripheral parasite density and gravidity, respectively. For the 2008–2009 study, CTX use was excluded from the final model due to expected co-linearity with HIV, as CTX is administered to HIV positive women. The final models derived for all three outcomes and for all three studies contained the variables: use of SP in pregnancy, maternal haemoglobin level at delivery, gravidity, logarithmic peripheral parasite density, HIV status, sample collection year, area of residence and number of msp2 clones. Given the different distributions of outcome genotype profiles for each study period, binary or cumulative logistic regressions were performed for each study separately. The proportional odds assumption was evaluated for cumulative logistic regression models using the score test, where P < 0.05 reflected a violation of the assumption. In addition, to ensure sufficient sample size in each category for analysis, some genotype categories were collapsed in both binary and cumulative logistic regression. The genotype outcome categories and logistic regression models used for each study period are described in detail in additional file [see Additional file 1]. All statistical tests were two-tailed and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Data analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA) and SAS version 9.2 (SAS Inc., NC, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

Clinical characteristics

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the pregnant women whose P. falciparum parasite positive samples were used in the current study. Use of SP in pregnancy among the participants differed significantly in the three study periods (P < 0.001), with an overall increase from 9.4 % in 1996–2000 study to 67.7 % in 2008–2009 study. In the 2008–2009 study, 23 % of the falciparum malaria parasite positive participants took CTX. There was a difference in mean age but no difference in the parity distribution among the three different studies and, for all three studies, primigravid women were predominant. Parasite density in the placenta was higher than in the periphery. Although there was no statistical difference in both peripheral and placental parasite density among the study periods, there was higher placental parasite density in the samples from 2008–2009 compared to those from 1996–2000 (P = 0.034). More than half of the pregnant women, irrespective of the study period, were anaemic at delivery. In addition, there was a difference in the proportion of HIV sero-positive samples that were used in this study, with a greater proportion of HIV positive samples used in 1996–2000 compared to in 2008–2009.

Prevalence of SNP mutations

Mutated amino acids and genetic codes are shown in bold font in Table 1. No mutations were detected at dhfr 50 and dhps 613 in any study period. However, the mutation at dhfr 164 was detected only in one sample each in 2002–2008 (0.6 %) and in 2008–2009 (0.8 %). In addition, the mutation at dhps position 581 was not detected prior to 2008, but was found in 5.3 % of the 2008–2009 samples. The prevalence of dhps 436 mutations including S436A, S436F, and S436H was 11.7 %, 2.8 % and 6.1 % for the three studies, respectively, among which the new 436 mutation, S436H, was detected in 2.3 % of 2002–2008 and 3.8 % of 2008–2009 samples. Overall, the prevalence of SNP mutations in dhfr 51, 59, 108 and dhps 437, 540 differed significantly among the three studies (P < 0.031), noticeably increasing from 78.9 % to 97.7 % (N51I), 51.7 % to 90.2 % (C59R), 97.8 % to 100 % (S108N), 42.8 % to 100 % (A437G) and 31.1 % to 99.2 % (K540E), respectively from 1996–2000 to 2008–2009 (Table 1).

Comparison of the prevalence of SP resistance markers, mean MOI and the number of clones between peripheral and placental samples

In order to assess if there were any notable differences between peripheral and placental parasites, SP-resistant genotypes, mean MOI and the distribution of the number of clones were compared in the peripheral and placental-paired samples from the 2008–2009 study period. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of the combined dhfr/dhps genotype in the peripheral and placental-paired samples (P = 0.54) (Figure 1A). In the analysis of mean MOI, the difference between periphery (1.11 ± 0.79) and placenta (1.32 ± 0.94) was not significant (P = 0.20). The number of distinguishable P. falciparum clones defined by msp 2 variant alleles ranged between one and four. No differences in the distribution of number of clones were found in the peripheral and placental-paired samples (P = 0.19) (Figure 1B).

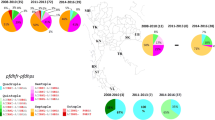

Temporal trends of dhfr, dhps and the combined dhfr/dhps genotypes

Figure 2 shows the temporal trends by the three study periods. The prevalence of the dhfr triple mutant (N51I/C59R/S108N) increased considerably from 27 % in 1996–2000 to 89 % in 2008–2009 and was significantly different across studies (P < 0.001), while the dhps double mutant (A437G/K540E) also increased from 27 % to 99 % and also differed significantly among studies (P < 0.001) [Figure 2A, B, respectively]. Figure 2C shows the temporal trends of the combined dhfr and dhps genotypes, based on the mutations at dhfr 51, 59, 108 and dhps 437, 540 classified as wild type, single, double, triple, quadruple, and quintuple. The prevalence of the quintuple mutant differed in the three studies (P < 0.001), increasing from 7 % in 1996–2000 to 88 % in 2008–2009. However, in all three studies, there were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of dhfr, dhps and the combined dhfr/dhps genotypes between the parasites samples from HIV + and HIV- women (see Additional file 2a, b, and c, respectively).

As the number of years for the three studies varied, particularly the wide range of years (2002–2008) for the second study, the prevalence data was further stratified by years and IPTp policy adoption (Figure 3). The prevalence of dhfr triple, dhps double and the combined dhfr/dhps quintuple mutants increased from 22.8 %, 19.5 % and 2.4 % in 1998 to 63.9 % (P < 0.001), 69.4 % (P < 0.001) and 44.4 % (P < 0.001), respectively, about three years after IPTp policy adoption (Figure 3). Subsequently, the prevalence of the drug-resistant molecular markers steadily increased, and by year 2009, the prevalence of the corresponding drug resistance mutant genotypes reached more than 90 % in the study population. In addition, Figure 3 shows that the percentage of participants who used SP during pregnancy after IPTp policy adoption seemingly parallels with the temporal trend for prevalence of drug resistant genotypes.

Prevalence of dhfr triple mutant, dhps double mutant and the combined dhfr / dhps quintuple genotype before and after IPTp policy adoption. Years with fewer than 25 samples were merged with either the previous year or after, depending on the number of samples in that particular year. The bars represent 95 % CI. No samples were collected in 2001 and therefore data for this year was not presented. For 1996–2000 and 2002–2008 periods, only history of SP use (case management or any dose of IPTp-SP) in pregnancy was documented while IPTp use was recorded for 2008–2009.

Table 2 shows the temporal change of three additional dhps combinations from 1996 to 2009. The dhps triple mutant which consists of the combination of mutations at dhps 436, 437 and 540 was not observed in the first study period but increased from 2.3 % in 2002–2008 study to 6 % in 2008–2009 study. In addition, the dhps triple mutant comprising of the combination of mutations at dhps 437, 540, and 581 was only detected at 5.3 % in 2008–2009 study. Furthermore, the combination of quadruple mutations at dhps 436, 437, 540 and 581, not previously detected in Kenya prior to 2008, showed a prevalence of 0.8 % in 2008–2009.

Assessment of association between use of SP in pregnancy and mutations in SP drug resistance genes

Since the increased prevalence in drug resistance molecular markers paralleled the increased use of SP during pregnancy as observed in Figure 3, the association between SP use in pregnancy and its effect on drug resistance molecular markers was further assessed. For the 1996–2000 study only, the unadjusted odds of having the dhps double mutant genotype among women who used SP was 3.5 [95 % CI, 1.3 to 9.6] times greater than the odds of women who did not use SP (Table 3). More mutations in the combined dhfr/dhps genotype were also associated with SP use during this study period (unadjusted OR, 4.2 [95 % CI, 1.6 to 10.9]). However, after adjusting for all other explanatory variables, neither association remained significant in multivariable analysis (Table 3). No other significant associations between the use of SP in pregnancy and mutations in dhfr, dhps and the combined dhfr/dhps genotypes were observed in the 2002–2008 and 2008–2009 study periods.

Prevalence of mixed infection and mean MOI over time

Previous studies suggest that transmission intensity or transmission reduction by ITNs could be one of factors that influence the prevalence of parasite drug resistance molecular markers [49, 50]. In order to estimate the change in transmission intensity during the study period and the possible effect of transmission reduction by ITN intervention on the parasite populations, the prevalence of mixed infection and MOI were measured by using size variant alleles of msp 2. Figure 4 shows that the prevalence of mixed infections decreased from 67.5 % in 1996–1998 to 18 % in 2009, although the highest prevalence of mixed infections was observed from 2004 to 2007 (87.1 % to 89.1 %, respectively) (P < 0.001). Likewise, the mean MOI also decreased significantly from 2.08 ± 0.96 to 1.00 ± 0.61 between 1996–1998 and 2009 while the highest mean MOI (2.94 ± 1.12 to 2.7 ± 0.99) was detected between 2004 and 2007 period (Figure 4) (P < 0.001).

Prevalence of mixed infection and mean MOI over time. Years with fewer than 25 samples were merged with either the previous year or after, depending on the number of samples in that particular year. No samples were collected in 2001 and therefore data for this year was not presented. The bars represent 95 % CI while mean MOI error bars represent SD. For 1996–2000 and 2002–2008 periods, only history of SP use (case management or any dose of IPTp-SP) in pregnancy was documented while IPTp use was recorded for 2008–2009.

Discussion

Anti-malarial drug resistance to SP, a factor contributing to diminishing therapeutic efficacy, is increasing in many malaria endemic countries. All African countries have already replaced SP with artemisinin-based combination therapy as the first line treatment for uncomplicated malaria, according to the WHO guidelines. However, SP remains the recommended drug for IPTp in malaria endemic areas. In this study, the temporal trends of SP resistance molecular markers in the parasites from Kenyan pregnant women and potential epidemiological factors affecting the prevalence of the resistant markers in the pregnant women were evaluated.

The key observations from this study were: 1) a noticeable background level of SP mutations in pregnant women prior to IPTp policy adoption, 2) a significant rise in the prevalence of the drug resistance markers after IPTp adoption seemingly in parallel with an increase in the percentage of SP use in pregnancy, and 3) however an association between more SNP mutations and SP use during pregnancy only in the 1996–2000 study in univariable analysis but not in 2002–2008 and 2008–2009 study periods. These results suggest that the increase in drug-resistant parasites in the pregnant women over time could be influenced by other major factors in addition to the minor role of IPTp adoption and SP use in pregnancy. Firstly, compared to high drug pressure in large general population (children and adults) due to SP use for case management, drug pressure in the small minority of pregnant women by IPTp-SP use is relatively lower. It is most likely that the resistant parasites selected by the use of SP for case management in the large general population could serve as the potential infectious reservoirs for pregnant women, thus high prevalence of drug resistant parasites circulated in the large non-pregnant population could contribute to the observed temporal increase in resistance markers in pregnant women. Indeed, the results from our previous study, conducted in the general population of the same area, showed that the prevalence of dhfr/dhps quintuple mutant parasites in children from the same study area increased from 29 % in 1996 to 62 % and 85 % in 2001 and 2007, respectively, after the drug policy change to SP for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria in 1998 [41]. Secondly, IPTp-SP works by intermittently clearing asymptomatic parasitaemia and preventing new infections in pregnant women [51] and the decreasing prevalence and intensity of infection in subsequent pregnancies also indicates the acquired immunity of the pregnant woman in preventing malaria infection as well as clearance of parasites [52]. Recent studies from several African countries reported increased prevalence of mutant genotypes due to IPTp-SP [33, 53, 54], but the increased resistant parasites did not affect the protective efficacy of IPTp [53, 54]. Based on the results from others [53, 54] and the molecular data from this study, the authors speculate that the interplay between IPTp-SP and host immunity in pregnant women could also play a role in the selection of drug resistant parasites, consequently shaping the parasite drug resistant profile in pregnant women. However, further studies are required to test this hypothesis. Lastly, the use of CTX as prophylaxis against opportunistic infection in HIV infected pregnant women, particularly the validated CTX use in the third study (2008–2009), might also contribute to the increased prevalence of SP drug resistant genotypes over time, possibly due to cross resistance between trimethoprim and pyrimethamine in P. falciparum malaria parasites [18]. Since multiple factors could be involved in the selection of resistant parasites in pregnant women, molecular markers when used alone may not accurately predict the failure of IPTp-SP. The assessment of the linkage between SP drug resistance molecular markers and efficacy of IPTp-SP in pregnant women in different malaria endemic areas becomes extremely important.

This study also detected 5.3 % of the dhps triple mutant (A437G/K540E/A581G) (7 samples), the presence of quadruple dhps mutant (S436A/F/H + A437G + K540E + A581G) (1 sample), the dhfr 164 (I164L) mutation (1 sample), and an increase in the new mutation at dhps S436H (5 samples) in the third study period (2008–2009). These results suggest progressive expansion of new mutations or new genotypes in parasite populations in Kenya. Although the contribution of the new mutation dhps S436H (unreported prior to this study) to drug resistance is unclear, the mutations at dhfr 164 and dhps 581 or related genotypes have been associated with a high-level of SP resistance mainly in Southeast Asia and South America [55, 56] and, more recently, have been reported on the African continent [26, 57–60]. Due to the small sample size in the new drug resistant genotype/SNP group, no further association analyses were conducted. However, higher placental parasite density in 2008–2009 period was observed as compared to the 1996–2000. It is possible that the progressive expansion of the new genotypes could be related to the overgrowth of resistant parasites, i.e. the highly resistant parasites out-compete less fit parasites [61–63]. Recent data from Tanzania suggest that the emergence of the dhps triple mutant (A437G/K540E/A581G) associated with the IPTp-SP use in pregnant women led to high-density parasitaemia [33]. Taken together, the emergence of new genotypes containing mutations in dhps 436 and dhps 581, coupled with the presence of dhfr 164 mutation in pregnant women may present a challenge for the future usefulness of IPTp-SP intervention in Kenya.

A recent study conducted in Mozambique reported that IPTp-SP use increased the prevalence of resistance markers in HIV positive women and mutant infections were more prevalent in placental than peripheral samples [36]. However, in this investigation, no statistical differences were found in the prevalence of dhps triple, dhps double and dhfr/dhps combined quintuple mutants between HIV positive and HIV negative women during all the three study periods. In the current study, there was also no significant difference in the prevalence of SP resistance markers and mean MOI between peripheral and placental-paired samples in the third study period when SP resistance was high. The discrepancy of the results between these two studies could be due to the differences in the study design, level of existing SP pressure and resistance, HIV care and other unknown factors. The Mozambique study used samples from a randomized double-blind, placebo-control trial of IPTp-SP conducted before IPTp-SP policy adoption, while the current study employed the samples collected from three different observational studies before and after IPTp-SP adoption for an extended period. However, the observation of no significant differences in mutant infections between placental and peripheral samples in the current study is consistent with the results from the studies conducted in Tanzania and Ghana, the countries with relative high levels of SP resistance [33, 64]. This suggests that either peripheral or placental samples can be used for monitoring drug resistant molecular markers in areas with high SP resistance level.

Overall, the prevalence of mixed infection and mean MOI decreased significantly between 1996 and 2009, but the highest parasite diversity was observed between the 2004 and 2007 period. The observed sharp increase in parasite diversity from 2004 could reflect the higher transmission intensity of the study site as the second malaria in pregnancy study was conducted from 2004 in the rural area (Siaya) where malaria transmission is relatively higher compared to Kisumu town. However, the drop in parasite diversity in 2008 followed by a significant decrease in 2009 might be related to the combination of transmission reduction by the implementation of free distribution of ITNs to pregnant women in ANC from early 2008 and SP use in pregnancy. The diversity of P. falciparum malaria reflects acquisition of new infections and is associated with transmission intensity [65]. A previous study conducted in Tanzania also showed that parasite diversity measured by msp2 was reduced in women with recent IPTp-SP use [33]. Nevertheless, the observation, overall decreased parasite diversity in conjunction with increased prevalence of drug resistance molecular markers over time in this study, suggests that intra-host removal of SP drug sensitive parasite clones is present, thus purifying drug resistant parasites in pregnant women.

There were few limitations to the current study. First, the present study utilized data from three different malaria in pregnancy observational studies and these three studies varied in their original study designs. Therefore, there were some differences in patient recruitment and procedures of clinical data collection, including assessment of IPTp use and use of SP for case management, which could have affected the statistical association analysis. Additionally, the lack of baseline samples from women prior to IPTp administration and absence of information for early versus later IPTp-SP or SP use before delivery limited the comparisons to assess the selection of drug resistant parasites in pregnant women whose immunity and pharmacokinetics are altered during pregnancy. Another limitation to the current study was the lack of samples from non-pregnant women as controls from the same study periods due to original design of the three previous observational studies. It will be ideal to conduct a well-controlled longitudinal IPTp drug resistance studies in both pregnant and non-pregnant women of the same population over a period of time. Such studies will help to examine the selection of drug resistant parasites and evaluate the potential factors involved in the development of SP resistance in pregnant women.

Conclusions

There was a significant increase in dhfr/dhps quintuple mutant and the emergence of new genotype containing dhps 581 and dhps S436H in the parasites from pregnant women in western Kenya over 13 years. IPTp adoption and SP use in pregnancy only played a minor role in the increased drug-resistant parasites in the pregnant women over time. Most likely, the high prevalence of resistant parasites selected by the use of SP for case management in large non-pregnant population in the same study area, CTX use, host immunity and transmission intensity might have contributed to the temporally increased prevalence of SP resistant parasites in pregnant women. Further investigations in the region to determine the linkage between SP drug resistance molecular markers and efficacy of IPTp-SP are needed.

References

Dellicour S, Tatem AJ, Guerra CA, Snow RW, ter Kuile FO: Quantifying the number of pregnancies at risk of malaria in 2007: a demographic study. PLoS Med. 2010, 7: e1000221-10.1371/journal.pmed.1000221.

WHO: Lives at risk: malaria in pregnancy. 2003, [http://www.who.int/features/2003/04b/en/] (Accessed 14 December 2010)

WHO: World Malaria Report 2008. 2008, WHO Press, Geneva, Switzerland

WHO: A strategic framework for malaria prevention and control during pregnancy in the Africa region. 2004, WHO Regional Office for Africa, Brazzaville, Congo, AFR/MAL/04/01

Maiga OM, Kayentao K, Traore BT, Djimde A, Traore B, Traore M, Ongoiba A, Doumtabe D, Doumbo S, Traore MS, Dara A, Guindo O, Karim DM, Coulibaly S, Bougoudogo F, Ter Kuile FO, Danis M, Doumbo OK: Superiority of 3 over 2 doses of intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine for the prevention of malaria during pregnancy in mali: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 53: 215-223. 10.1093/cid/cir374.

Goodman CA, Coleman PG, Mills AJ: The cost-effectiveness of antenatal malaria prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 2001, 64: 45-56.

Sicuri E, Bardaji A, Nhampossa T, Maixenchs M, Nhacolo A, Nhalungo D, Alonso PL, Menendez C: Cost-effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy in southern Mozambique. PLoS One. 2010, 5: e13407-10.1371/journal.pone.0013407.

Shulman CE, Dorman EK, Cutts F, Kawuondo K, Bulmer JN, Peshu N, Marsh K: Intermittent sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine to prevent severe anaemia secondary to malaria in pregnancy: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 1999, 353: 632-636. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07318-8.

Asa OO, Onayade AA, Fatusi AO, Ijadunola KT, Abiona TC: Efficacy of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine in preventing anaemia in pregnancy among Nigerian women. Matern Child Health J. 2008, 12: 692-698. 10.1007/s10995-008-0319-3.

Parise ME, Ayisi JG, Nahlen BL, Schultz LJ, Roberts JM, Misore A, Muga R, Oloo AJ, Steketee RW: Efficacy of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine for prevention of placental malaria in an area of Kenya with a high prevalence of malaria and human immunodeficiency virus infection. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 1998, 59: 813-822.

ter Kuile FO, van Eijk AM, Filler SJ: Effect of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance on the efficacy of intermittent preventive therapy for malaria control during pregnancy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007, 297: 2603-2616. 10.1001/jama.297.23.2603.

Oyibo WA, Agomo CO: Scaling up of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine: prospects and challenges. Matern Child Health J. 2011, 15: 542-552. 10.1007/s10995-010-0608-5.

Aziken ME, Akubuo KK, Gharoro EP: Efficacy of intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine on placental parasitemia in pregnant women in midwestern Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011, 112: 30-33. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.07.027.

Kayentao K, Kodio M, Newman RD, Maiga H, Doumtabe D, Ongoiba A, Coulibaly D, Keita AS, Maiga B, Mungai M, Parise ME, Doumbo O: Comparison of intermittent preventive treatment with chemoprophylaxis for the prevention of malaria during pregnancy in Mali. J Infect Dis. 2005, 191: 109-116. 10.1086/426400.

Sirima SB, Cotte AH, Konate A, Moran AC, Asamoa K, Bougouma EC, Diarra A, Ouedraogo A, Parise ME, Newman RD: Malaria prevention during pregnancy: assessing the disease burden one year after implementing a program of intermittent preventive treatment in Koupela District, Burkina Faso. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 2006, 75: 205-211.

Menendez C, Bardaji A, Sigauque B, Sanz S, Aponte JJ, Mabunda S, Alonso PL: Malaria prevention with IPTp during pregnancy reduces neonatal mortality. PLoS One. 2010, 5: e9438-10.1371/journal.pone.0009438.

Barat LM, Bloland PB: Drug resistance among malaria and other parasites. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1997, 11: 969-987. 10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70400-1.

Iyer JK, Milhous WK, Cortese JF, Kublin JG, Plowe CV: Plasmodium falciparum cross-resistance between trimethoprim and pyrimethamine. Lancet. 2001, 358: 1066-1067. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06201-8.

Nosten F, McGready R, d’Alessandro U, Bonell A, Verhoeff F, Menendez C, Mutabingwa T, Brabin B: Antimalarial drugs in pregnancy: a review. Curr Drug Saf. 2006, 1: 1-15. 10.2174/157488606775252584.

Peterson DS, Walliker D, Wellems TE: Evidence that a point mutation in dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase confers resistance to pyrimethamine in falciparum malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988, 85: 9114-9118. 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9114.

Triglia T, Menting JG, Wilson C, Cowman AF: Mutations in dihydropteroate synthase are responsible for sulfone and sulfonamide resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997, 94: 13944-13949. 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13944.

Lozovsky ER, Chookajorn T, Brown KM, Imwong M, Shaw PJ, Kamchonwongpaisan S, Neafsey DE, Weinreich DM, Hartl DL: Stepwise acquisition of pyrimethamine resistance in the malaria parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009, 106: 12025-12030. 10.1073/pnas.0905922106.

Hamel MJ, Poe A, Bloland P, McCollum A, Zhou Z, Shi YP, Ouma P, Otieno K, Vulule J, Escalante A, Udhayakumar V, Slutsker L: Dihydrofolate reductase I164L mutations in Plasmodium falciparum isolates: clinical outcome of 14 Kenyan adults infected with parasites harbouring the I164L mutation. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008, 102: 338-345. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.01.018.

Lynch C, Pearce R, Pota H, Cox J, Abeku TA, Rwakimari J, Naidoo I, Tibenderana J, Roper C: Emergence of a dhfr mutation conferring high-level drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum populations from southwest Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2008, 197: 1598-1604. 10.1086/587845.

Nzila AM, Mberu EK, Sulo J, Dayo H, Winstanley PA, Sibley CH, Watkins WM: Towards an understanding of the mechanism of pyrimethamine-sulphadoxine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum: genotyping of dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase of Kenyan parasites. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000, 44: 991-996. 10.1128/AAC.44.4.991-996.2000.

Gesase S, Gosling RD, Hashim R, Ord R, Naidoo I, Madebe R, Mosha JF, Joho A, Mandia V, Mrema H, Mapunda E, Savael Z, Lemnge M, Mosha FW, Greenwood B, Roper C, Chandramohan D: High resistance of Plasmodium falciparum to sulphadoxine/pyrimethamine in northern Tanzania and the emergence of dhps resistance mutation at Codon 581. PLoS One. 2009, 4: e4569-10.1371/journal.pone.0004569.

Alifrangis M, Lusingu JP, Mmbando B, Dalgaard MB, Vestergaard LS, Ishengoma D, Khalil IF, Theander TG, Lemnge MM, Bygbjerg IC: Five-year surveillance of molecular markers of Plasmodium falciparum antimalarial drug resistance in Korogwe District, Tanzania: accumulation of the 581G mutation in the P. falciparum dihydropteroate synthase gene. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 2009, 80: 523-527.

Spalding MD, Eyase FL, Akala HM, Bedno SA, Prigge ST, Coldren RL, Moss WJ, Waters NC: Increased prevalence of the pfdhfr/phdhps quintuple mutant and rapid emergence of pfdhps resistance mutations at codons 581 and 613 in Kisumu. Kenya. Malar J. 2010, 9: 338-

Kublin JG, Dzinjalamala FK, Kamwendo DD, Malkin EM, Cortese JF, Martino LM, Mukadam RA, Rogerson SJ, Lescano AG, Molyneux ME, Winstanley PA, Chimpeni P, Taylor TE, Plowe CV: Molecular markers for failure of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine and chlorproguanil-dapsone treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis. 2002, 185: 380-388. 10.1086/338566.

Happi CT, Gbotosho GO, Folarin OA, Akinboye DO, Yusuf BO, Ebong OO, Sowunmi A, Kyle DE, Milhous W, Wirth DF, Oduola AM: Polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum dhfr and dhps genes and age related in vivo sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance in malaria-infected patients from Nigeria. Acta Trop. 2005, 95: 183-193. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.06.015.

Sridaran S, McClintock SK, Syphard LM, Herman KM, Barnwell JW, Udhayakumar V: Anti-folate drug resistance in Africa: meta-analysis of reported dihydrofolate reductase (dhfr) and dihydropteroate synthase (dhps) mutant genotype frequencies in African Plasmodium falciparum parasite populations. Malar J. 2010, 9: 247-10.1186/1475-2875-9-247.

WHO: Report of the technical expert group meeting on intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp). 2008, World Health Organization, Geneva, Geneva, 2007 July 11–13

Harrington WE, Mutabingwa TK, Muehlenbachs A, Sorensen B, Bolla MC, Fried M, Duffy PE: Competitive facilitation of drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites in pregnant women who receive preventive treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009, 106: 9027-9032. 10.1073/pnas.0901415106.

Harrington WE, Mutabingwa TK, Kabyemela E, Fried M, Duffy PE: Intermittent treatment to prevent pregnancy malaria does not confer benefit in an area of widespread drug resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 53: 224-230. 10.1093/cid/cir376.

Falade CO, Yusuf BO, Fadero FF, Mokuolu OA, Hamer DH, Salako LA: Intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine is effective in preventing maternal and placental malaria in Ibadan, south-western Nigeria. Malar J. 2007, 6: 88-10.1186/1475-2875-6-88.

Menendez C, Serra-Casas E, Scahill MD, Sanz S, Nhabomba A, Bardaji A, Sigauque B, Cistero P, Mandomando I, Dobano C, Alonso PL, Mayor A: HIV and placental infection modulate the appearance of drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in pregnant women who receive intermittent preventive treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 52: 41-48. 10.1093/cid/ciq049.

Ayisi JG, van Eijk AM, Newman RD, ter Kuile FO, Shi YP, Yang C, Kolczak MS, Otieno JA, Misore AO, Kager PA, Lal RB, Steketee RW, Nahlen BL: Maternal malaria and perinatal HIV transmission, western Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004, 10: 643-652. 10.3201/eid1004.030303.

Perrault SD, Hajek J, Zhong K, Owino SO, Sichangi M, Smith G, Shi YP, Moore JM, Kain KC: Human immunodeficiency virus co-infection increases placental parasite density and transplacental malaria transmission in Western Kenya. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 2009, 80: 119-125.

van Eijk AM, Blokland IE, Slutsker L, Odhiambo F, Ayisi JG, Bles HM, Rosen DH, Adazu K, Lindblade KA: Use of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in pregnancy in a rural area of western Kenya with high coverage of insecticide-treated bed nets. Trop Med Int Health. 2005, 10: 1134-1140. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01497.x.

Watsierah CA, Jura WG, Oyugi H: Abong'o B. Ouma C: Factors determining anti-malarial drug use in a peri-urban population from malaria holoendemic region of western Kenya. Malar J. 2010, 9: 295-

Shah M, Kariuki S, Vanden Eng J, Blackstock AJ, Garner K, Gatei W, Gimnig JE, Lindblade K, Terlouw D, ter Kuile F, Hawley WA, Phillips-Howard P, Nahlen B, Walker E, Hamel MJ, Slutsker L, Shi YP: Effect of transmission reduction by insecticide-treated bednets (ITNs) on antimalarial drug resistance in western Kenya. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e26746-10.1371/journal.pone.0026746.

Pearce RJ, Drakeley C, Chandramohan D, Mosha F, Roper C: Molecular determination of point mutation haplotypes in the dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase of Plasmodium falciparum in three districts of northern Tanzania. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003, 47: 1347-1354. 10.1128/AAC.47.4.1347-1354.2003.

Alker AP, Mwapasa V, Meshnick SR: Rapid real-time PCR genotyping of mutations associated with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004, 48: 2924-2929. 10.1128/AAC.48.8.2924-2929.2004.

Zhou Z, Poe AC, Limor J, Grady KK, Goldman I, McCollum AM, Escalante AA, Barnwell JW, Udhayakumar V: Pyrosequencing, a high-throughput method for detecting single nucleotide polymorphisms in the dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthetase genes of Plasmodium falciparum. J Clin Microbiol. 2006, 44: 3900-3910. 10.1128/JCM.01209-06.

Alam MT, de Souza DK, Vinayak S, Griffing SM, Poe AC, Duah NO, Ghansah A, Asamoa K, Slutsker L, Wilson MD, Barnwell JW, Udhayakumar V, Koram KA: Selective sweeps and genetic lineages of Plasmodium falciparum drug-resistant alleles in Ghana. J Infect Dis. 2011, 203: 220-227. 10.1093/infdis/jiq038.

Snounou G, Zhu X, Siripoon N, Jarra W, Thaithong S, Brown KN, Viriyakosol S: Biased distribution of msp1 and msp2 allelic variants in Plasmodium falciparum populations in Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999, 93: 369-374. 10.1016/S0035-9203(99)90120-7.

WHO: Recommended genotyping procedures (RGPs) to indentify parasite populations. Developed after an informal consultation organized by the Medicines for Malaria Venture and cosponsored by the World Health Organization, 29–31 May 2007. 2008, WHO, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1-44.

Farnert A, Arez AP, Babiker HA, Beck HP, Benito A, Bjorkman A, Bruce MC, Conway DJ, Day KP, Henning L, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Ranford-Cartwright LC, Rubio JM, Snounou G, Walliker D, Zwetyenga J, do Rosario VE: Genotyping of Plasmodium falciparum infections by PCR: a comparative multicentre study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001, 95: 225-232. 10.1016/S0035-9203(01)90175-0.

Hastings IM, Watkins WM: Intensity of malaria transmission and the evolution of drug resistance. Acta Trop. 2005, 94: 218-229. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.04.003.

Alifrangis M, Lemnge MM, Ronn AM, Segeja MD, Magesa SM, Khalil IF, Bygbjerg IC: Increasing prevalence of wildtypes in the dihydrofolate reductase gene of Plasmodium falciparum in an area with high levels of sulphadoxine/pyrimethamine resistance after introduction of treated bed nets. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 2003, 69: 238-243.

Peters PJ, Thigpen MC, Parise ME, Newman RD: Safety and toxicity of sulphadoxine/pyrimethamine: implications for malaria prevention in pregnancy using intermittent preventive treatment. Drug Saf. 2007, 30: 481-501. 10.2165/00002018-200730060-00003.

Rogerson SJ, Wijesinghe RS, Meshnick SR: Host immunity as a determinant of treatment outcome in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010, 10: 51-59. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70322-6.

Mockenhaupt FP, Bedu-Addo G, Eggelte TA, Hommerich L, Holmberg V, von Oertzen C, Bienzle U: Rapid increase in the prevalence of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance among Plasmodium falciparum isolated from pregnant women in Ghana. J Infect Dis. 2008, 198: 1545-1549. 10.1086/592455.

Bertin G, Briand V, Bonaventure D, Carrieu A, Massougbodji A, Cot M, Deloron P: Molecular markers of resistance to sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine during intermittent preventive treatment of pregnant women in Benin. Malar J. 2011, 10: 196-10.1186/1475-2875-10-196.

Le Bras J, Durand R: The mechanisms of resistance to antimalarial drugs in Plasmodium falciparum. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2003, 17: 147-153. 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00164.x.

Vinayak S, Alam MT, Mixson-Hayden T, McCollum AM, Sem R, Shah NK, Lim P, Muth S, Rogers WO, Fandeur T, Barnwell JW, Escalante AA, Wongsrichanalai C, Ariey F, Meshnick SR, Udhayakumar V: Origin and evolution of sulphadoxine resistant Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6: e1000830-10.1371/journal.ppat.1000830.

Alker AP, Mwapasa V, Purfield A, Rogerson SJ, Molyneux ME, Kamwendo DD, Tadesse E, Chaluluka E, Meshnick SR: Mutations associated with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine and chlorproguanil resistance in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Blantyre, Malawi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005, 49: 3919-3921. 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3919-3921.2005.

Gebru-Woldearegai T, Hailu A, Grobusch MP, Kun JF: Molecular surveillance of mutations in dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase genes of Plasmodium falciparum in Ethiopia. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 2005, 73: 1131-1134.

A-Elbasit IE, Alifrangis M, Khalil IF, Bygbjerg IC, Masuadi EM, Elbashir MI, Giha HA: The implication of dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthetase gene mutations in modification of Plasmodium falciparum characteristics. Malar J. 2007, 6: 108-10.1186/1475-2875-6-108.

Wang P, Lee CS, Bayoumi R, Djimde A, Doumbo O, Swedberg G, Dao LD, Mshinda H, Tanner M, Watkins WM, Sims PF, Hyde JE: Resistance to antifolates in Plasmodium falciparum monitored by sequence analysis of dihydropteroate synthetase and dihydrofolate reductase alleles in a large number of field samples of diverse origins. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997, 89: 161-177. 10.1016/S0166-6851(97)00114-X.

de Roode JC, Culleton R, Bell AS, Read AF: Competitive release of drug resistance following drug treatment of mixed Plasmodium chabaudi infections. Malar J. 2004, 3: 33-10.1186/1475-2875-3-33.

Wargo AR, Huijben S, de Roode JC, Shepherd J, Read AF: Competitive release and facilitation of drug-resistant parasites after therapeutic chemotherapy in a rodent malaria model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007, 104: 19914-19919. 10.1073/pnas.0707766104.

Schneider P, Chan BH, Reece SE, Read AF: Does the drug sensitivity of malaria parasites depend on their virulence?. Malar J. 2008, 7: 257-10.1186/1475-2875-7-257.

Mockenhaupt FP, Bedu-Addo G, Junge C, Hommerich L, Eggelte TA, Bienzle U: Markers of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in placenta and circulation of pregnant women. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007, 51: 332-334. 10.1128/AAC.00856-06.

Kiwanuka GN: Genetic diversity in Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 and 2 coding genes and its implications in malaria epidemiology: a review of published studies from 1997–2007. J Vector Borne Dis. 2009, 46: 1-12.

Acknowledgements

We show appreciation to all the participating women for their involvement in the current study. Our thanks also extend to the many staff in Kenya who conducted the malaria in pregnancy studies, including sample and data collection and data management, during the three different study periods. NC Iriemenam was supported by the American Society for Microbiology (ASM) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Postdoctoral Fellowship (ASM/CDC Research Fellowship Program). We thank the director of the Kenyan Medical Research Institute for his approval of publishing this article. This study was supported by intramural funding from the Office of Antimicrobial Resistance, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Project ID#921ZJQH).

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the United States Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author’s contributions

NCI, MS, WG, SK, AAL and YOO carried out genotyping work for the current study. AME, JA, FOK, BN (first period), JM, SOO (second period), MD, MJH, PO, and LS (third period) implemented the observational malaria in pregnancy studies from 1996 to 2009 including enrolment of patients and collection of clinical and epidemiological data and samples. YPS conceived, designed and supervised the current study. NCI, MS and JVE did the statistical analysis. NCI, MS and YPS wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results and critical discussion of the conclusion and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12936_2012_2106_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Statistical procedure. The file described the statistical methods used for the descriptive and association analysis. (DOC 47 KB)

12936_2012_2106_MOESM2_ESM.tiff

Additional file 2: Proportion of SP drug resistant genotypes by HIV status and by study period. A, dhfr genotypes. B, dhps genotypes. C, combined dhfr/dhps genotypes. The figures described the prevalence of dhfr, dhps and the combined dhfr/dhps genotypes between HIV + and HIV- women. (TIFF 361 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Iriemenam, N.C., Shah, M., Gatei, W. et al. Temporal trends of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) drug-resistance molecular markers in Plasmodium falciparum parasites from pregnant women in western Kenya. Malar J 11, 134 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-11-134

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-11-134