Abstract

Background

Production of monoterpenoids as valuable chemicals using recombinant microbes is a growing field of interest. Unfortunately, antimicrobial activity of most monoterpenoids hampers a wide application of microorganisms for their production. Strains of Pseudomonas putida, a fast growing and metabolically versatile bacterium, often show an outstanding high tolerance towards organic solvents and other toxic compounds. Therefore, Pseudomonas putida constitutes an attractive alternative host in comparison to conventionally used microorganisms. Here, metabolic engineering of solvent tolerant Pseudomonas putida as a novel microbial cell factory for de novo production of monoterpenoids is reported for the first time, exemplified by geranic acid production from glycerol as carbon source. The monoterpenoic acid is an attractive compound for application in the flavor, fragrance, cosmetics and agro industries.

Results

A comparison between Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pseudomonas putida concerning the ability to grow in the presence of geranic acid revealed that the pseudomonad bears a superior resilience compared to the conventionally used microbes. Moreover, Pseudomonas putida DSM 12264 wildtype strain efficiently oxidized externally added geraniol to geranic acid with no further degradation. Omitting external dosage of geraniol but functionally expressing geraniol synthase (GES) from Ocimum basilicum, a first proof-of-concept for de novo biosynthesis of 1.35 mg/L geranic acid in P. putida DSM 12264 was achieved. Doubling the amount of glycerol resulted in twice the amount of product. Co-expression of the six genes of the mevalonate pathway from Myxococcus xanthus to establish flux from acetyl-CoA to the universal terpenoid precursor isopentenylpyrophosphate yielded 36 mg/L geranic acid in shake flask experiments. In the bioreactor, the recombinant strain produced 193 mg/L of geranic acid under fed-batch conditions within 48 h.

Conclusion

Metabolic engineering turned Pseudomonas putida DSM 12264, a versatile monoterpenoid oxidation biocatalyst, into an efficient microbial cell factory for de novo geranic acid production. Improvements by metabolic and process engineering are expected to further increase the product concentration. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first example of a de novo production of a monoterpenoid with Pseudomonas putida and of a microbial monoterpenoic acid synthesis in general.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Terpenoids constitute the most diverse group of natural products with more than 40,000 structurally different molecules identified in nature [1], of which more than 1,000 compounds belong to the subclass of monoterpenoids [2]. Terpenoids are widely applied as flavor and fragrance compounds, colorants, nutraceuticals, pharmaceuticals, agrichemicals etc. [1]. Since these biomolecules, especially their oxyfunctionalized derivatives, are often naturally produced in only small amounts, approaches for their production others than isolation from natural raw materials are very much sought. Since chemical synthesis often starts from fossil raw materials and can be costly, especially for stereo- and/or regioselectively oxyfunctionalized terpenoids, biotechnological production starting from cheap renewable substrates offers a highly attractive alternative. In their pioneering work, J.D. Keasling and co-workers comprehensively engineered Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae towards microbial cell factories for the production of the sesquiterpenoids amorpha-4,11-diene and artemisinic acid [3–6]. Nowadays, high concentrations regarding the production of secondary metabolites of up to the grams per liter range are reported for sesquiterpenoids already in shake flask cultures [7–9], but monoterpenoid production using similarly engineered microbial hosts as platform strains is usually still limited to product titers in the lower milligrams per liter range [10,11]. The toxicity of monoterpenoids is referred to as the main bottleneck hampering their efficient microbial production or biotransformation [12,13]. It was shown that monoterpenoids, such as thymol, menthol, linalyl acetate, α-pinene and β-pinene, preferentially intercalate into the cell membrane resulting in an increase of membrane fluidity which eventually leads to loss of vital membrane functions and cell death [14–16]. For baker’s yeast, the cell wall instead of the membrane was recently shown to be the site of the destructive action of externally added limonene [17]. Pseudomonas putida, a Gram-negative γ-proteobacterium, possesses the outstanding ability to tolerate high concentrations of different hydrocarbons, though great differences in the degree of resilience occur among different strains. Several mechanisms to counteract organic solvent toxicity are described for P. putida such as reinforcing the membrane phospholipid bilayer by cis-to-trans isomerization of unsaturated fatty acids, increasing the ratio of saturated-to-unsaturated fatty acids, and active export of toxic compounds via efflux pumps [18,19]. A couple of industrial processes with P. putida have already been established [20] and more wildtype and recombinant P. putida strains have been recently described for potential industrial de novo production of toxic aromatic compounds such as phenol [21] and p-hydroxybenzoate [22] or for biotransformation of toxic precursors such as toluene to o-cresol [23] or the monoterpenoid limonene to perillic acid [24]. This illustrates the potential of this species as an alternative host for biotechnological applications, especially if toxic substrates or products are dealt with. However, de novo monoterpenoid production with P. putida has not been reported until the present work.

The aim of our present study was to investigate the potential of a solvent tolerant P. putida strain to be engineered as a microbial cell factory for de novo production of monoterpenoids. We chose P. putida DSM 12264 and geranic acid as our model strain and product, respectively, for three reasons: i) we knew from our previous work that this strain is highly robust in the presence of limonene even up to volume shares which form a distinct separate organic phase in the bioreactor [24], ii) previous work with this strain [25] as well as unpublished own pre-investigations revealed that the wildtype strain is also resilient against other monoterpenoids and it can convert the monoterpene alcohol geraniol to geranic acid, and iii) geranic acid has great potential for different industrially relevant applications. Geranic acid can be used as a perfuming agent [26] and is an important building block for the production of natural flavor esters [27]. Moreover, it shows strong antifungal properties against two main phytopathogens of corn, Colletotrichum graminicola and Fusarium graminearum, and was therefore produced in a transgenic maize plant to improve resistance against the fungal attack [28]. Furthermore, this monoterpenoid is known to inhibit tyrosinase, a key enzyme of melanogenesis in mammalian cells [29]. Lately, Choi showed that geranic acid has depigmenting properties in melanocytes combined with low cell toxicity which makes this compound attractive as skin depigmentation agent [30].

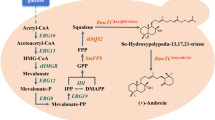

Here, we introduced genes for a truncated geraniol synthase (GES) from sweet basil Ocimum basilicum [31] and the complete mevalonate (MVA) pathway from the Gram-negative bacterium Myxococcus xanthus into P. putida DSM 12264. The recombinant strain was able to produce geranic acid without significant terpenoid by-product formation and, due to its monoterpenoid robustness, may serve as a platform strain for monoterpenoid production in the future.

Results

Suitability of P. putida as a host for geranic acid production

To verify the expected advantage of P. putida for monoterpenoid production compared with conventional host strains, i.e. an assumed superior product tolerance, growth assays with P. putida DSM 12264, E. coli DH5α and S. cerevisiae CEN.PK2-1C in the presence of geranic acid were performed (Figure 1). According to Brennan and colleagues, shake flasks with screw caps were used for growth experiments to avoid monoterpenoid evaporation [32]. Growth of S. cerevisiae strongly decreased when geranic acid concentrations were increased and was completely inhibited at 2 mM geranic acid, whereas E. coli growth became significantly affected by geranic acid starting from concentrations of 5 mM and was completely inhibited at a concentration of 7 mM. For P. putida, cell growth was distinctly impaired at 20 mM but did not cease even at the highest geranic acid concentration tested, which was 40 mM.

Growth inhibition of S. cerevisiae , E. coli and P. putida by geranic acid. Indicated are the ratios of the maximum growth rate at given geranic acid concentrations (μmax) to the maximum growth rate without monoterpenoid (μmax0) at different geranic acid concentrations for S. cerevisiae, E. coli and P. putida. Cells were grown in screw cap shake flasks in complex medium and different geranic acid amounts were added at the beginning of the exponential phase. Samples were taken for OD measurements to calculate μmax. Mean values of two independent experiments, indicated by error bars, are given.

To exclude biodegradation and bioconversion of the desired product by P. putida DSM 12264, utilization of geranic acid by this bacterium and product stability were examined. Neither biodegradation nor bioconversion of geranic acid was observed (data not shown). Furthermore, P. putida KT2440 was also tested for geraniol oxidation, since this strain is far better described in literature than P. putida DSM 12264 [33]. This strain showed a geranic acid tolerance similar to P. putida DSM 12264 and no further metabolization of this monoterpenoic acid could be observed as well (data not shown).

Biotransformation of geraniol to geranic acid by wildtype P. putida DSM 12264

Pseudomonads are known to have strong oxidation capabilities towards different hydrocarbons. Besides the oxidation of monoterpene hydrocarbons, such as limonene or the pinenes, Pseudomonas species have also been shown to oxidize monoterpene aldehydes, such as citral or citronellal, and monoterpene alcohols, such as linalool or nerol [34]. To demonstrate the natural capacity of geraniol oxidation in cells of P. putida DSM 12264, different amounts of geraniol were added to growing cells in E2 medium and resulting geranic acid concentrations were determined at different time points within 64 h (Figure 2). Up to 16 mM geraniol were nearly completely oxidized within the tested time period. With an initial substrate concentration of 32 mM, a maximum product concentration of 23 mM was obtained. Furthermore, the oxidation rate decreased at 32 mM and 64 mM (for t =8 h, geranic acid concentrations were significantly (p <0.05, Tukey’s HSD) lower than at 4 mM, 8 mM and 16 mM geraniol). For more information about the statistical analysis, please see Additional file 1. Cell growth slowed down at 8 mM geraniol and was distinctly impaired at 16 mM (data not shown). Cell lysis was observed at 32 mM and higher concentrations after 36 h (data not shown), while oxidation rate decreased correspondingly.

Whole cell biotransformation of geraniol by P. putida DSM 12264 wildtype strain. Indicated are the concentrations of produced geranic acid at different time points by whole cell biotransformation of geraniol by P. putida DSM 12264 wildtype. Different amounts of geraniol were added to growing cells in E2 medium (containing 10% LB and 30 mg/L kanamycin, 4.6 g/L glycerol) and geranic acid concentration was quantified after 8, 16, 32, 38 and 64 h. For 2, 4 and 8 mM geraniol, respectively, the last sample was taken after 32 h due to complete geraniol depletion and maximum product concentration. Experiments were run in triplicates. For detailed statistical analysis, please see Additional file 1.

These data illustrate the high geraniol oxidation capacity of P. putida DSM 12264 with a maximum geranic acid production rate over the first 32 h of ~0.43 mM/h. In contrast, an about 50% lower product formation rate and a maximum product concentration of 5 mM geranic acid were observed for P. putida KT2440 (data not shown).

Geranic acid production of P. putida DSM 12264 expressing GES

To implement de novo geraniol production in P. putida, the gene of geraniol synthase (GES) from O. basilicum, encoding the enzyme converting the cellular terpenoid biosynthesis intermediate geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) to geraniol, was introduced via plasmid pMiS1 (Additional file 2). Recombinant cells were cultivated in E2 medium (containing 10% LB) for 3 h, before gene expression was induced by addition of 0.2% (w/v) L-rhamnose (t = 0, Figure 3). A maximum concentration of 0.6 μM geraniol was measured after 5 h followed by continuous depletion, while geranic acid accumulated simultaneously, ending up with a maximum concentration of 8 μM (ca. 1.3 mg/L) after about 21 h. No geraniol and geranic acid was detected in cultures of P. putida DSM 12264 containing an empty vector (for statistical analysis, see Additional file 3).

Production of geraniol and geranic acid by P. putida DSM 12264 expressing GES. Indicated are the concentrations of de novo produced geraniol (blue) and geranic acid (red) over time using P. putida DSM 12264 expressing GES. Cells were grown in shake flasks in E2 medium (containing 10% LB and 30 mg/L kanamycin, 4.6 g/L glycerol) at 30°C and GES expression was induced 3 h after inoculation with 0.2% (w/v) L-rhamnose. Triangles indicate P. putida DSM 12264 with empty plasmid, circles indicate P. putida DSM 12264 pMiS1-ges. Geraniol and geranic acid concentrations were determined via HPLC over time. Mean values of two independent experiments, indicated by error bars, are given. For detailed statistical analysis, please see Additional file 3.

Geranic acid production in P. putida DSM 12264 coexpressing GES and MVA pathway

The efficiency of microbial terpenoid production is limited by the flux from intermediates of the central metabolism, i.e. acetyl-CoA (MVA pathway) or pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (2-C-methylerythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway) towards the terpene synthase substrates geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP), farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) or geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP). This has already been overcome by different approaches, e.g. by overexpression of genes of the terpenoid biosynthesis or the elimination of feedback inhibition mechanisms [35]. The prime example of synthetic biology for microbial terpenoid production is the successful heterologous expression of the MVA pathway in E. coli increasing intracellular FPP concentration which greatly improved the yield of sesquiterpene amorpha-4,11-diene [3] and laid the foundation for a series of step-wise further strain improvements.

Following this concept to increase carbon flux towards terpenoid synthesis, 6 genes encoding the MVA pathway of M. xanthus leading from acetyl-CoA to isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) together with the geraniol synthase gene from O. basilicum were introduced into P. putida DSM 12264 in the present work. In contrast to previously shown experiments, twice the amount of glycercol (9.2 g/L instead of 4.6 g/L) was used for the medium to prevent growth-limiting effects. The geraniol production/depletion and concurrent geranic acid production profiles obtained (Figure 4) look similar to the profiles of the strain lacking the MVA pathway (Figure 3) but with significantly higher maximum terpenoid concentrations (p <0.01, Tukey’s HSD, Additional file 4). About 3 μM of geraniol accumulated in 5 h after induction of heterologous gene expression. Geraniol concentration decreased after 5 h and was not detectable anymore after 2 days, whereas geranic acid steadily accumulated concurrently. A maximum concentration of 215 μM geranic acid was obtained after 2 days.

Production of geraniol and geranic acid by P. putida DSM 12264 expressing GES and MVA. Indicated are the concentrations of de novo produced geraniol (blue) and geranic acid (red) over time using P. putida DSM 12264 expressing GES and MVA. Cells were grown in shake flasks in E2 medium (containing 10% LB, 30 mg/L kanamycin and 9.2 g/L glycerol) at 30°C and heterologous gene expression was induced 3 h after inoculation with 0.2% (w/v) L-rhamnose. Geraniol and geranic acid concentrations were determined via HPLC over time. Mean values of two independent experiments, indicated by error bars, are given. For detailed statistical analysis, please see Additional file 4.

Geranic acid production in the fed-batch bioreactor

P. putida DSM 12264 coexpressing GES and the MVA pathway was tested under controlled conditions in the bioreactor. After cells were grown for 24 h, protein expression was induced (t = 0). Samples for OD600 measurement and HPLC analysis were taken over time for three days; the results are shown in Figure 5. Highest cell density of OD600 66 was obtained after 24 h and a total of 1.15 mM geranic acid was produced after 2 days.

Production of geranic acid by P. putida DSM 12264 expressing GES and MVA in a fed-batch bioprocess. Indicated are the OD600 value (blue) and the concentration of de novo produced geranic acid (red) over time using P. putida DSM 12264 expressing GES and MVA in the bioreactor. Cells were grown in a bioreactor in E2 medium (containing 10% LB and 30 mg/L kanamycin, 4.6 g/L glycerol) for 24 h before induction of gene expression with 0.2% (w/v) L-rhamnose (t = 0). Geranic acid concentration was determined via HPLC over time. Mean values of two independent experiments, indicated by error bars, are given.

Discussion

P. putida DSM 12264 is a suitable microbe for geraniol to geranic acid conversion

Many P. putida strains are known, which are highly tolerant towards organic solvents. Since bacterial monoterpenoid toxicity is an obstacle for E. coli and S. cerevisiae as terpenoid production hosts [32,36], P. putida DSM 12264, known for its high monoterpenoid tolerance [24], was tested as a host for de novo production of geranic acid. This strain turned out to be significantly more tolerant to geranic acid than E. coli and S. cerevisiae (Figure 1). Besides, the pseudomonad is able to completely and efficiently oxidize up to 16 mM geraniol. As a consequence, inhibition of cell growth by geraniol as an intermediate is not expected to be a bottleneck during de novo production of geranic acid.

Some pseudomonads, such as P. aeruginosa, P. citronellolis and P. mendocina, are known to utilize geraniol and geranic acid as sole carbon sources whereas P. putida is usually not able to assimilate neither of the substances [37,38]. Oxidation of geraniol to the corresponding acid by the upper part of the acyclic terpene utilization (atu) pathway is assumed to be the inital step in geraniol degradation [39]. Furthermore, a pyrroloquinoline quinone dependent alcohol dehydrogenase (QEDH) encoded by the exaA gene was found to participate in geraniol oxidation in P. aeruginosa as well [40]. Therefore, oxidoreductases homologous to AtuB and AtuG of the atu pathway [39] or QEDH [40] are likely to be responsible for geraniol oxidation in P. putida DSM 12264 as well, although it cannot be excluded, whether nonspecific oxidoreductases are involved as well. These oxidoreductases are promising candidates for further optimization of the geraniol oxidation power of the strain.

The demonstration of high geranic acid tolerance combined with an efficient geraniol oxidation pathway and the inability to degrade geranic acid laid the foundation to engineer P. putida DSM 12264 towards a microbial cell factory for de novo production of geranic acid.

De novo production of geranic acid by recombinant P. putida DSM 12264

Geraniol synthase (GES) from O. basilicum was shown to be functionally expressed in E. coli and S. cerevisiae and de novo geraniol production was already successfully demonstrated in both microbes [31,41,42]. Karst and co-workers obtained a de novo geraniol concentration of about 10 mg/L in yeast after optimization of GPP synthase activity to increase the GPP pool [43] and optimization of GES activity [44]. More recently, a geraniol concentration of 36 mg/L was reported for yeast after metabolic engineering of the intrinsic MVA pathway [45]. In the present work, naturally geraniol oxidizing P. putida DSM 12264 was chosen as host for functional expression of GES to accomplish direct de novo production of the desired oxidation product of geraniol, geranic acid. Glycerol was chosen as the carbon source since this compound is cheap and abundantly available as the main by-product of biodiesel production [46]. Transient accumulation of geraniol indicated fast but delayed oxidation of the monoterpene alcohol to geranic acid by endogenous enzymes. As the product was found in the supernatant without significant residual material left in the cells, product recovery in a later bioprocess will be facilitated.

Metabolic engineering of pathways leading to elevated terpenoid precursor levels is a common approach in biotechnological terpenoid production [47]. In E. coli, the recombinant MVA pathway from S. cerevisiae proved to be efficient [3,48], even though expression of some of the yeast enzymes revealed to be not balanced in E. coli [8,49,50]. Approaches replacing yeast genes hmgr and hmgs with their orthologues from Staphylococcus aureus [51,52] led to significant increases in production rates. An entirely prokaryotic MVA pathway was shown to enhance the coenzyme Q10 production in E. coli [53]. The bacterium M. xanthus possesses a complete MVA pathway where 5 of the 6 required genes are organized in an operon that eases a straightforward cloning procedure. We therefore tested the influence of the MVA pathway of M. xanthus on geranic acid production in P. putida DSM 12264 expressing GES (Figure 4). A final concentration of 215 μM (36.2 mg/L) of geranic acid was obtained after 2 days of cultivation, corresponding to a more than 10-fold increase compared to the strain without M. xanthus MVA pathway (p <0.01, Tukey’s HSD, Additional file 4), demonstrating the pronounced positive effect of the MVA pathway on terpenoid production in P. putida DSM 12264. Since the intrinsic GPP pool is assumed to be limiting as well, additional GPP synthases such as ERG20-2 from S. cerevisiae [54] or IDS from Picea abies [55] may further increase product formation. Furthermore, ribosome binding sites (RBS) of the FPP biosynthesis genes can be optimized, which led to a considerable increase in amorphadiene yield with E. coli [56]. Besides, homologous overexpression of the MEP pathway to enhance terpenoid precursors as an alternative route can be considered as well, since overexpression of this pathway was shown to benefit carotene production in P. putida KT2440 [57]. These options will be content of further work to enhance product formation.

De novo production of geranic acid with P. putida DSM 12264 in a fed-batch bioreactor

Since P. putida DSM 12264 was previously shown to be an efficient whole cell biocatalyst for limonene biotransformation under process conditions due to high monoterpenoid tolerance and ease of cultivation [24], we tested the performance of the recombinant P. putida bearing GES and the MVA pathway in the bioreactor as well. Geranic acid concentration increased rapidly and continuously after induction. A maximum OD600 of 66 after 24 h and a final concentration of 1.15 mM (193 mg/L) geranic acid were obtained after 48 h, corresponding to a specific product yield of 9.7 mg/g cdw, below but in the same order of magnitude as compared with the value of 13.9 mg/g cdw obtained in the shake flask experiments. Comparable product yields between 7 and 17.6 mg/g cdw were recently obtained for limonene with different E. coli strains harboring the MVA pathway [58]. Significantly higher ratios of about 230 mg/g cdw of limonene and about 65 mg/g cdw of perillyl alcohol were obtained by Alonso-Gutierrez and co-workers [51] with an engineered MVA containing E. coli strain, assuming an average correlation of cdw [g/L] = OD600 [−] ∙0.46 [59]. In both experiments, a second organic phase was used for in situ product removal of the produced monoterpenoids. Since P. putida DSM 12264 is able to tolerate distinctly higher concentrations of geranic acid (see Figure 1) as those produced in the present work, inhibiting effects of the product on cell growth can be excluded. In contrast, engineered S. cerevisiae would have probably not been capable of producing a similar amount of product, as the yeast growth was already severely inhibited by 1 mM geranic acid (only 36% of μmax0, see Figure 1). E. coli wildtype significantly lost viability above 5 mM geranic acid, indicating that it could still be a production host for geranic acid competitive to our current data obtained with P. putida DSM 12264, providing that an additional heterologous expression of a geraniol-to-geranic acid pathway is feasible in E. coli. On the contrary, if the target molecules are not monoterpenoic acids but instead monoterpene alcohols, such as perillyl alcohol or geraniol, the pronounced oxidative capacity of P. putida DSM 12264 will be a disadvantage due to unwanted overoxidation as shown in a recent comparison of recombinant E. coli and P. putida for whole cell bioconversion of limonene to perillyl alcohol [60]. Identifying endogenous genes responsible for overoxidation, e.g. those for the geraniol-to-geranic acid conversion, followed by a targeted knock-out could be a solution if specific monoterpene alcohols (or ketones/aldehydes) are sought. The identification of oxidizing enzymes may also lead to a modular pathway design for P. putida to de novo synthesize monoterpenoids of a desired oxyfunctionalization degree. Here, we intentionally coupled an MVA pathway enhanced terpenoid biosynthesis with a plant monoterpene synthase and a so far unknown endogenous oxyfunctionalization pathway in P. putida. In pre-investigations (Becher et al., unpublished), P. putida DSM 12264 heterologously expressing Mentha spicata limonene synthase instead of O. basilicum geraniol synthase produced small amounts of perillic acid, as expected. However, since limonene, in contrast to geraniol, is a very cheap natural precursor abundantly available from renewable resources (by-product of the citrus processing industry) and perillic acid can be efficiently obtained in concentrations of up to 30 g/L through bioconversion of limonene as shown in our previous work [24], we focused on geranic acid in the present work. Nevertheless, this underpins the feasibility of turning P. putida DSM 12264 into a cell factory for de novo production of different monoterpenoids, especially different monoterpenoic acids. So far, the potential of P. putida DSM 12264 for geranic acid production has not yet been fully harnessed, as the strain is not significantly growth-inhibited at product concentrations of up to 15 mM. Therefore, there is still room for a 10-fold increase in final product concentration by metabolic engineering means without expecting a negative impact on the growth performance of the host. The maximum cell density of OD600 66 corresponding to 19.8 g cdw/L obtained with P. putida DSM 12264 in the fed-batch process is still moderate. Thus, optimization of the bioprocess based on published protocols for high-cell density fermentations of P. putida [61–64] should be feasible and may lead to significant higher biomass and product concentrations. Finally, solvent tolerant bacteria such as P. putida are ideal microbes to be used in aqueous-organic two-phase fermentations [19] or in the presence of adsorbers [24] for in situ product removal, which facilitates the development of high-perfomance integrated bioprocesses.

Conclusion

Engineering P. putida for de novo production of a monoterpenoid was shown for the first time. The solvent tolerant strain P. putida DSM 12264, originally used as a robust wildtype whole cell biocatalyst for production of perillic acid from limonene [24], was shown to possess a strong oxidative capacity and efficiently converted geraniol to geranic acid. Introducing MVA pathway and geraniol synthase turned P. putida DSM 12264 into a microbial cell factory for de novo production of geranic acid from the renewable carbon source glycerol. P. putida DSM 12264 was shown to be of superior geranic acid tolerance compared to the conventional microbial hosts E. coli and S. cerevisiae. Being tolerant against different monoterpenoids, viable even in the presence of a separate monoterpenoid phase under process conditions [24], and genetically well accessible make this strain a highly promising platform for monoterpenoid production in the future.

Materials and methods

Chemicals, wildtype strains and media

Geranic acid (85%), geraniol (98%) and thymol (99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany). (L)-(+)-Rhamnose monohydrate, glycerol and hexane (≥99%) were purchased from Carl Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany).

For growth assays, P. putida strain DSM 12264, S. cerevisiae strain CEN.PK2-1C [65] and E. coli strain DH5α [66] were used. Each organism was grown in complex medium: terrific broth (TB) for P. putida, yeast medium (YM) for S. cerevisiae and lysogeny broth (LB) for E. coli. Additionally, LB was used as preculture medium for geranic acid production experiments with P. putida. For whole cell de novo syntheses, E2 medium [25] containing 10% LB was used. For PCR amplification of the MVA pathway genes, DNA of M. xanthus DSM 16526 was used.

Plasmid construction and transformation

The gene encoding a GES lacking the signal peptide encoding region from O. basilicum was amplified from plasmid pMO5 [41]. The 6 genes of the MVA pathway, namely HMG-CoA synthase (hmgs), HMG-CoA reductase (hmgr), mevalonate kinase (mvk), phosphomevalonate kinase (pmvk), diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase (mvd) and isopentenyldiphosphateisomerase (idi), were amplified from genomic DNA of M. xanthus. Primers used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

For gene expression in P. putida DSM 12264, plasmid pMiS1 was used which was derived from pJeM1 [67] by exchange of the eGFP gene with a synthetically constructed multiple cloning site sequence. Single stranded sense primer pJeM1-MCS-f and antisense strand primer pJeM1-MCS-r comprising the rhamnose-inducible promoter rhaPBAD, a ribosome binding site, a multiple cloning site (MCS) and 5′-phosphorylations were ordered from Sigma Aldrich. The promoter and the ribosome binding site were re-inserted with the new MCS since the original parts were cut out with egfp due to restriction sites limitations. After hybridization, the DNA fragment was ligated into EcoRI and HindIII precut pJeM1 backbone.

The ges gene was amplified from pMO5 [41] using primers GES-fwd and GES-rev and cloned via KpnI and SacI into pMiS1 to give pMiS1-ges. The MVA pathway genes of M. xanthus are genomically organized as a single gene (hmgs) and an operon containing the rest of the genes (idi, hmgr, mvd, mvk, pmvk). For cloning of these MVA pathway genes into pMiS1, hmgs was first amplified from genomic M. xanthus DNA using the primers pMiS1-hmgs-f (containing an upstream Shine-Dalgarno sequence) and pMiS1-hmgs-r and cloned via BamHI and HindIII into pMiS1 yielding pMiS1-hmgs. Then, the operon (containing all other genes) was cloned sequentially into pUC18. Three amplifications were performed using primers pMiS1-MVA-f1, pMiS1-MVA-r1 (part1, containing an upstream Shine-Dalgarno-sequence), pMiS1-MVA-f2, pMiS1-MVA-r2 (part 2) and pMiS1-MVA-f3, pMiS1-MVA-r3 (part 3). Parts were ligated using BamHI, SacI and EcoRI as restriction sites. The new operon comprising all 5 genes was then cut from resulting pUC18-mva-op via AvrII and HindIII and ligated into pMiS1-hmgs to give pMiS1-mva. The ges gene was then cut from pMiS1-ges and ligated into pMiS1-mva using PmeI and BamHI to give pMiS1-ges-mva. For a schematic of the cloning strategy, please see Additional file 2.

P. putida DSM 12264 was transformed by electroporation [68]. Recombinant cells were selected on LB agar containing 30 mg/L kanamycin.

Growth, metabolization and bioconversion assays

The inhibitory effect of geranic acid on the growth of E. coli, S. cerevisiae or P. putida was investigated. To avoid terpenoid evaporation, 100 mL baffled flasks with screw caps were used for growth assays. For all microbes, 20 mL complex medium were inoculated with an optical density (OD600) of 0.2 from an overnight preculture and cultivated at 180 rpm shaking (2.5 cm displacement). S. cerevisiae and P. putida were cultivated at 30°C; E. coli was cultivated at 37°C. For each organism, a specific range of geranic acid concentrations was chosen, in which inhibiting effects occur. Geranic acid was added directly or from ethanolic stock solutions at the beginning of the exponential growth phase (after 1 h of cultivation for E. coli and P. putida and after 3 h for S. cerevisiae). Controls with the highest applied ethanol concentrations were tested simultaneously and no inhibiting effects of ethanol on microbial growth could be observed. Samples were taken during exponential growth phase every 30 min for E. coli and P. putida and every hour for S. cerevisiae and OD600 was determined. All experiments were performed in duplicates. For each growth curve, μmax was determined at the exponential growth phase immediately after geranic acid addition and divided by μmax0 of the culture without geranic acid.

For metabolization tests with geraniol as sole carbon source, P. putida cells were grown in complex medium overnight and plated on E2 minimal medium lacking glycerol. Geraniol was applied as vapor phase. Water was used as negative control and p-cymene as positive control, since P. putida DSM 12264 is known to grow on this aromatic compound [25]. Cell growth was monitored for 94 h at 30°C. For metabolization tests with geranic acid as the sole carbon source, 20 mL E2 medium lacking glycerol with 20 mM geranic acid was inoculated using 1 mL of a P. putida overnight culture. No carbon source was applied for the negative control and 20 mM p-cymene was applied as positive control. Cell growth was monitored via OD600 determination for 144 h at 30°C.

Stability tests with geranic acid and whole cell biotransformation with geraniol were performed with P. putida cells in 50 mL and 20 mL E2 medium, respectively, containing corresponding terpenoid concentrations. Medium was inoculated with TB preculture of P. putida at an initial OD600 of 0.2. Geranic acid concentrations at different time points were determined by HPLC analysis.

De novo geranic acid synthesis

All cultures of recombinant P. putida strains contained 30 mg/L kanamycin for plasmid selection. Precultures were inoculated from cryo cultures using 5 mL LB with antibiotic and incubated overnight at 30°C and 180 rpm shaking (2.5 cm displacement). Main cultures of 50 mL E2 medium (containing 10% LB) in 300 mL Erlenmeyer flasks were then inoculated using 0.5 mL of precultures. Main cultures were incubated at 30°C and 180 rpm shaking frequency (2.5 cm displacement). Gene expression was induced after 3 h with 0.2% (w/v) L-rhamnose. Samples were taken and stored at −20°C until sample preparation.

HPLC analysis

To P. putida culture samples of 500 μL or 1 mL, 50 μL or 100 μL 1 M HCl were added, respectively, and analytes were extracted using 500 μL hexane containing 200 μM thymol as an internal standard. For bioconversion assays, 1 mM thymol was used. Samples were centrifuged (5 min, 18,000 g) and the organic phase was analyzed by HPLC, consisting of a diode array detector and a C-18 column (Alltech Alltima, C18, 5 μm, 250 × 4,6 mm; C18 Precolumn, Grace GmbH and Co. KG, Worms). Substances were separated isocratically using acetonitrile/acidified water (containing 0.5% (v/v) 3 M phosphoric acid) in a ratio of 55:45 (v/v) as mobile phase. Geraniol and thymol were monitored at 202 nm, geranic acid at 217 nm.

Fed-batch fermentation

De novo geranic acid production in the bioreactor was performed using a DASGIP SR0700ODLS system (DASGIP, Jülich, Germany). 5 mL of LB precultures with 30 mg/L kanamycin were used to inoculate 500 mL E2 medium (containing 10% LB and 30 mg/L kanamycin). Main cultures were incubated for 24 h at 30°C with 50 mL/h aeration and 30% saturation of dissolved oxygen (DO). Glycerol (612 g/L) and MgSO4 (10 g/L) feed was triggered by DO (50 mL/h feed rate). The pH was maintained at 6.9 by automatic addition of ammonia. GES expression was induced by addition of L-rhamnose after 24 h of incubation (t = 0) to a concentration of 0.2% (w/v) and aeration rate was lowered to 10 mL/h, DO limited to a saturation of 10% and a feed rates of 10 mL/h (glycerol and MgSO4) for the production phase. Samples were taken over time and prepared for HPLC analysis as described above.

Abbreviations

- GES:

-

Geraniol synthase

- MVA:

-

Mevalonate

- OD600 :

-

Optical density at 600 nm

- GPP:

-

Geranyl pyrophosphate

- FPP:

-

Farnesyl pyrophosphate

- IPP:

-

Isopentenyl pyrophosphate

- DMAPP:

-

Dimethylallyl pyrophosphate

- HPLC:

-

High pressure liquid chromatography

- DO:

-

Dissolved oxygen

References

Bution ML, Molina G, Abrahao MR, Pastore GM: Genetic and metabolic engineering of microorganisms for the development of new flavor compounds from terpenic substrates. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2014:1–13. doi:10.3109/07388551.2013.855161

Breitmaier E: Terpene: Aromen, Düfte, Pharmaka, Pheromone. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2005.

Martin VJ, Pitera DJ, Withers ST, Newman JD, Keasling JD: Engineering a mevalonate pathway in Escherichia coli for production of terpenoids. Nat Biotechnol 2003, 21:796–802.

Shiba Y, Paradise EM, Kirby J, Ro DK, Keasling JD: Engineering of the pyruvate dehydrogenase bypass in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for high-level production of isoprenoids. Metab Eng 2007, 9:160–168.

Ro DK, Paradise EM, Ouellet M, Fisher KJ, Newman KL, Ndungu JM, Ho KA, Eachus RA, Ham TS, Kirby J, Chang MC, Withers ST, Shiba Y, Sarpong R, Keasling JD: Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature 2006, 440:940–943.

Paddon CJ, Westfall PJ, Pitera DJ, Benjamin K, Fisher K, McPhee D, Leavell MD, Tai A, Main A, Eng D, Polichuk DR, Teoh KH, Reed DW, Treynor T, Lenihan J, Fleck M, Bajad S, Dang G, Dengrove D, Diola D, Dorin G, Ellens KW, Fickes S, Galazzo J, Gaucher SP, Geistlinger T, Henry R, Hepp M, Horning T, Iqbal T, et al: High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature 2013, 496:528–532.

Scalcinati G, Knuf C, Partow S, Chen Y, Maury J, Schalk M, Daviet L, Nielsen J, Siewers V: Dynamic control of gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae engineered for the production of plant sesquitepene α-santalene in a fed-batch mode. Metab Eng 2012, 14:91–103.

Anthony JR, Anthony LC, Nowroozi F, Kwon G, Newman JD, Keasling JD: Optimization of the mevalonate-based isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli for production of the anti-malarial drug precursor amorpha-4, 11-diene. Metab Eng 2009, 11:13–19.

Peralta-Yahya PP, Ouellet M, Chan R, Mukhopadhyay A, Keasling JD, Lee TS: Identification and microbial production of a terpene-based advanced biofuel. Nat Commun 2011, 2:483.

Sarria S, Wong B, Martin HG, Keasling JD, Peralta-Yahya P: Microbial synthesis of pinene. ACS Synth Biol 2014 in press (DOI:10.1021/sb4001382).

Yang J, Nie Q, Ren M, Feng H, Jiang X, Zheng Y, Liu M, Zhang H, Xian M: Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the biosynthesis of alpha-pinene. Biotechnol Biofuels 2013, 6:60.

van der Werf MJ, De Bont JAM, Leak DJ: Opportunities in microbial biotransformation of monoterpenes. In Biotechnology of Aroma Compounds, Volume 55. Edited by Scheper T. Berlin: Springer; 1997:283.

Tippmann S, Chen Y, Siewers V, Nielsen J: From flavors and pharmaceuticals to advanced biofuels: production of isoprenoids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Biotechnol J 2013, 8:1435–1444.

Trombetta D, Castelli F, Sarpietro MG, Venuti V, Cristani M, Daniele C, Saija A, Mazzanti G, Bisignano G: Mechanisms of antibacterial action of three monoterpenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005, 49:2474–2478.

Uribe S, Ramirez J, Peña A: Effects of beta-pinene on yeast membrane functions. J Bacteriol 1985, 161:1195–1200.

Andrews RE, Parks LW, Spence KD: Some effects of Douglas fir terpenes on certain microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol 1980, 40:301–304.

Brennan TC, Kromer JO, Nielsen LK: Physiological and transcriptional responses of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to d-limonene show changes to the cell wall but not to the plasma membrane. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013, 79:3590–3600.

Ramos JL, Duque E, Gallegos M-T, Godoy P, Ramos-González MI, Rojas A, Terán W, Segura A: Mechanisms of solvent tolerance in gram-negative bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 2002, 56:743–768.

Heipieper HJ, Neumann G, Cornelissen S, Meinhardt F: Solvent-tolerant bacteria for biotransformations in two-phase fermentation systems. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2007, 74:961–973.

Poblete-Castro I, Becker J, Dohnt K, Dos Santos VM, Wittmann C: Industrial biotechnology of Pseudomonas putida and related species. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2012, 93:2279–2290.

Wierckx NJ, Ballerstedt H, de Bont JA, Wery J: Engineering of solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida S12 for bioproduction of phenol from glucose. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005, 71:8221–8227.

Meijnen JP, Verhoef S, Briedjlal AA, de Winde JH, Ruijssenaars HJ: Improved p-hydroxybenzoate production by engineered Pseudomonas putida S12 by using a mixed-substrate feeding strategy. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 90:885–893.

Faizal I, Dozen K, Hong CS, Kuroda A, Takiguchi N, Ohtake H, Takeda K, Tsunekawa H, Kato J: Isolation and characterization of solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida strain T-57, and its application to biotransformation of toluene to cresol in a two-phase (organic-aqueous) system. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2005, 32:542–547.

Mirata MA, Heerd D, Schrader J: Integrated bioprocess for the oxidation of limonene to perillic acid with Pseudomonas putida DSM 12264. Process Biochem 2009, 44:764–771.

Speelmans G, Bijlsma A, Eggink G: Limonene bioconversion to high concentrations of a single and stable product, perillic acid, by a solvent-resistant Pseudomonas putida strain. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 1998, 50:538–544.

Bedoukian PZ: Perfumery and Flavoring Synthetics. Wheaton: Allured Publishing Corporation; 1986.

Schrader J: Microbial Flavour Production. In Flavours and Fragrances. Edited by Berger RG. Berlin: Springer; 2007:507–574.

Yang T, Stoopen G, Yalpani N, Vervoort J, de Vos R, Voster A, Verstappen FW, Bouwmeester HJ, Jongsma MA: Metabolic engineering of geranic acid in maize to achieve fungal resistance is compromised by novel glycosylation patterns. Metab Eng 2011, 13:414–425.

Wang N, Hebert DN: Tyrosinase maturation through the mammalian secretory pathway: bringing color to life. Pigment Cell Res 2006, 19:3–18.

Choi SY: Inhibitory effects of geranic acid derivatives on melanin biosynthesis. J Cosmet Sci 2012, 63:351–358.

Iijima Y, Gang DR, Fridman E, Lewinsohn E, Pichersky E: Characterization of geraniol synthase from the peltate glands of sweet basil. Plant Physiol 2004, 134:370–379.

Brennan TCR, Turner CD, Krömer JO, Nielsen LK: Alleviating monoterpene toxicity using a two-phase extractive fermentation for the bioproduction of jet fuel mixtures in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Biotechnol Bioeng 2012, 109:2513–2522.

Nelson KE, Weinel C, Paulsen IT, Dodson RJ, Hilbert H, Santos VAP M d, Fouts DE, Gill SR, Pop M, Holmes M, Brinkac L, Beanan M, DeBoy RT, Daugherty S, Kolonay J, Madupu R, Nelson W, White O, Peterson J, Khouri H, Hance I, Lee PC, Holtzapple E, Scanlan D, Tran K, Moazzez A, Utterback T, Rizzo M, Lee K, Kosack D, et al: Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the metabolically versatile Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ Microbiol 2002, 4:799–808.

Schrader J, Berger RG: Biotechnological production of terpenoid flavor and fragrance compounds. In Biotechnology: Special Processes, Volume 10. Edited by Rehm HJ, Reed G. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2001:373–422.

Chandran SS, Kealey JT, Reeves CD: Microbial production of isoprenoids. Process Biochem 2011, 46:1703–1710.

Dunlop MJ, Dossani ZY, Szmidt HL, Chu HC, Lee TS, Keasling JD, Hadi MZ, Mukhopadhyay A: Engineering microbial biofuel tolerance and export using efflux pumps. Mol Sys Biol 2011, 7:487.

Cantwell SG, Lau EP, Watt DS, Fall RR: Biodegradation of acyclic isoprenoids by Pseudomonas species. J Bacteriol 1978, 135:324–333.

Vandenbergh PA, Wright AM: Plasmid involvement in acyclic isoprenoid metabolism by Pseudomonas putida . Appl Environ Microbiol 1983, 45:1953–1955.

Forster-Fromme K, Jendrossek D: Identification and characterization of the acyclic terpene utilization gene cluster of Pseudomonas citronellolis . FEMS Microbiol Lett 2006, 264:220–225.

Chattopadhyay A, Förster-Fromme K, Jendrossek D: PQQ-Dependent Alcohol Dehydrogenase (QEDH) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is involved in catabolism of acyclic terpenes. J Basic Microbiol 2010, 50:119–124.

Oswald M, Fischer M, Dirninger N, Karst F: Monoterpenoid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . FEMS Yeast Res 2007, 7:413–421.

Fischer MJ, Meyer S, Claudel P, Perrin M, Ginglinger JF, Gertz C, Masson JE, Werck-Reinhardt D, Hugueney P, Karst F: Specificity of Ocimum basilicum geraniol synthase modified by its expression in different heterologous systems. J Biotech 2013, 163:24–29.

Fischer MJ, Meyer S, Claudel P, Bergdoll M, Karst F: Metabolic engineering of monoterpene synthesis in yeast. Biotechnol Bioeng 2011, 108:1883–1892.

Fischer MJ, Meyer S, Claudel P, Steyer D, Bergdoll M, Hugueney P: Determination of amino-acidic positions important for Ocimum basilicum geraniol synthase activity. Adv Biosci Biotechnol 2013, 4:242–249.

Liu J, Zhang W, Du G, Chen J, Zhou J: Overproduction of geraniol by enhanced precursor supply in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J Biotech 2013, 168:446–451.

da Silva GP, Mack M, Contiero J: Glycerol: a promising and abundant carbon source for industrial microbiology. Biotechnol Adv 2009, 27:30–39.

Peralta-Yahya PP, Zhang F, Del Cardayre SB, Keasling JD: Microbial engineering for the production of advanced biofuels. Nature 2012, 488:320–328.

Morrone D, Lowry L, Determan MK, Hershey DM, Xu M, Peters RJ: Increasing diterpene yield with a modular metabolic engineering system in E. coli : comparison of MEV and MEP isoprenoid precursor pathway engineering. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2010, 85:1893–1906.

Pitera DJ, Paddon CJ, Newman JD, Keasling JD: Balancing a heterologous mevalonate pathway for improved isoprenoid production in Escherichia coli . Metab Eng 2007, 9:193–207.

Redding-Johanson AM, Batth TS, Chan R, Krupa R, Szmidt HL, Adams PD, Keasling JD, Soon Lee T, Mukhopadhyay A, Petzold CJ: Targeted proteomics for metabolic pathway optimization: application to terpene production. Metab Eng 2011, 13:194–203.

Alonso-Gutierrez J, Chan R, Batth TS, Adams PD, Keasling JD, Petzold CJ, Lee TS: Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for limonene and perillyl alcohol production. Metab Eng 2013, 19:33–41.

Tsuruta H, Paddon CJ, Eng D, Lenihan JR, Horning T, Anthony LC, Regentin R, Keasling JD, Renninger NS, Newman JD: High-level production of amorpha-4, 11-diene, a precursor of the antimalarial agent artemisinin, in Escherichia coli . PLoS One 2009, 4:e4489.

Zahiri HS, Yoon SH, Keasling JD, Lee SH, Won Kim S, Yoon SC, Shin YC: Coenzyme Q10 production in recombinant Escherichia coli strains engineered with a heterologous decaprenyl diphosphate synthase gene and foreign mevalonate pathway. Metab Eng 2006, 8:406–416.

Blanchard L, Karst F: Characterization of a lysine-to-glutamic acid mutation in a conservative sequence of farnesyl diphosphate synthase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Gene 1993, 125:185–189.

Schmidt A, Gershenzon J: Cloning and characterization of two different types of geranyl diphosphate synthases from Norway spruce ( Picea abies ). Phytochemistry 2008, 69:49–57.

Nowroozi F, Baidoo EK, Ermakov S, Redding-Johanson A, Batth T, Petzold C, Keasling J: Metabolic pathway optimization using ribosome binding site variants and combinatorial gene assembly. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2013, 98:1567–1581.

Beuttler H, Hoffmann J, Jeske M, Hauer B, Schmid RD, Altenbuchner J, Urlacher VB: Biosynthesis of zeaxanthin in recombinant Pseudomonas putida . Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 89:1137–1147.

Willrodt C, David C, Cornelissen S, Buhler B, Julsing MK, Schmid A: Engineering the productivity of recombinant Escherichia coli for limonene formation from glycerol in minimal media. Biotechnol J 2014 in press (doi:10.1002/biot.201400023).

Myers JA, Curtis BS, Curtis WR: Improving accuracy of cell and chromophore concentration measurements using optical density. BMC Biophys 2013, 6:4.

Cornelissen S, Julsing MK, Volmer J, Riechert O, Schmid A, Bühler B: Whole-cell-based CYP153A6-catalyzed (S)-limonene hydroxylation efficiency depends on host background and profits from monoterpene uptake via AlkL. Biotechnol Bioeng 2013, 110:1282–1292.

Kim GJ, Lee IY, Choi DK, Yoon SC, Park YH: High cell density cultivation of Pseudomonas putida MB01 using glucose. J Microbiol Biotechnol 1996, 6:221–224.

Thuesen MH, Norgaard A, Hansen AM, Caspersen MB, Christensen HE: Expression of recombinant Pseudomonas stutzeri di-heme cytochrome c4 by high-cell-density fed-batch cultivation of Pseudomonas putida . Protein Expr Purif 2003, 27:175–181.

Sun Z, Ramsay J, Guay M, Ramsay B: Automated feeding strategies for high-cell-density fed-batch cultivation of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2006, 71:423–431.

Ramadhan S, Matsui T, Nakano K, Minami H: High cell density cultivation of Pseudomonas putida strain HKT554 and its application for optically active sulfoxide production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2013, 97:1903–1907.

Entian K-D, Kötter P: 23 yeast mutant and plasmid collections. Methods Microbiol 1998, 26:431–449.

Bethesda_Research_Laboratories: BRL pUC host: E. coli DH5α™ competent cells. Bethesda Res Lab Focus 1986, 8:9–12.

Jeske M, Altenbuchner J: The Escherichia coli rhamnose promoter rhaP(BAD) is in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 independent of Crp-cAMP activation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2010, 85:1923–1933.

Choi KH, Kumar A, Schweizer HP: A 10-min method for preparation of highly electrocompetent Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells: application for DNA fragment transfer between chromosomes and plasmid transformation. J Microbiol Methods 2006, 64:391–397.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Josef Altenbuchner (University of Stuttgart) for kindly providing plasmid pJeM1. The authors thank Prof. Francis Karst (University of Strasbourg) for kindly providing plasmid pMO5. This work was supported by FNR, Fachagentur für nachwachsende Rohstoffe e.V., (No. 22040011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DB and JM performed the growth experiments and together with MB drafted the manuscript. DB, JM and PL carried out the plasmid construction. JM was responsible for editorial handling and statistical analysis. PL performed the shake flask experiments with production strains. SD performed the fermentation experiments. JM, KT and HS performed the terpenoid bioconversion and metabolization experiments. JS conceived the work and together with MB designed and supervised the experiments and they wrote the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jia Mi and Daniela Becher contributed equally to this work.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Statistical analysis of the dataset of biotransformation of geraniol to geranic acid by wildtype P. putida DSM 12264 (Figure 2 ).

Additional file 2:

Schematic of the cloning procedure leading to the plasmids pMiS1, pMiS1-ges, pUC18-mva-op, pMiS1-hmgs, pMiS1-mva and pMiS1-ges-mva, respectively.

Additional file 3:

Statistical analysis of the dataset of de novo production of geranic acid by P. putida DSM 12264 harboring ges (Figure 3 ).

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Mi, J., Becher, D., Lubuta, P. et al. De novo production of the monoterpenoid geranic acid by metabolically engineered Pseudomonas putida . Microb Cell Fact 13, 170 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-014-0170-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-014-0170-8