Abstract

Background

It remains to be elucidated whether dipeptidylpeptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor can ameliorate cardiovascular injury in salt-sensitive hypertension. The present study was undertaken to test our hypothesis that linagliptin, a DPP-4 inhibitor, administration initiated after onset of hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy can ameliorate cardiovascular injury in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats (DS rats).

Methods

High-salt loaded DS rats with established hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy were divided into two groups, and were orally given (1) vehicle or (2) linagliptin (3 mg/kg/day) once a day for 4 weeks, and cardiovascular protective effects of linagliptin in DS rats were evaluated.

Results

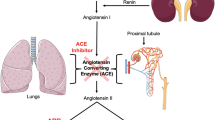

Linagliptin did not significantly affect blood pressure and blood glucose levels in DS rats. Linagliptin significantly lessened cardiac hypertrophy in DS rats, as estimated by cardiac weight and echocardiographic parameters. Linagliptin significantly ameliorated cardiac fibrosis, cardiac macrophage infiltration, and coronary arterial remodeling in DS rats. Furthermore, linagliptin significantly mitigated the impairment of vascular function in DS rats, as shown by the improvement of acetylcholine-induced or sodium nitroprusside-induced vascular relaxation by linagliptin. These cardiovascular protective effects of linagliptin were associated with the attenuation of oxidative stress, NADPH oxidase subunits, p67phox and p22 phox, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE).

Conclusions

Our results provided the experimental evidence that linagliptin treatment initiated after the appearance of hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy protected against cardiovascular injury induced by salt-sensitive hypertension, independently of blood pressure and blood glucose. These beneficial effects of linagliptin seem to be attributed to the reduction of oxidative stress and ACE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of cardiovascular disease begins with risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, etc. [1]. Strict blood pressure control and lipid control are well known to definitely reduce cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. On the other hand, there has been controversy regarding whether strict glycemic control can reduce cardiovascular disease (macrovascular disease) in type 2 diabetic patients [2]-[5], although diabetic microvascular complication such as nephropathy, retinopathy, or neuropathy is demonstrated to be reduced by strict glycemic control. This uncertainty about the efficacy of the conventional glucose-lowering therapies on cardiovascular outcome emphasizes the need for novel antidiabetic agents with the benefits in prevention of diabetic macrovascular complication.

Dipeptidylpeptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors are a new class of blood glucose-lowering drug, have been approved for treatment of type 2 diabetes, and take the advantage of having low risk of hypoglycemia and neutral effect on body weight [6]-[9]. DPP-4 inhibitors inhibit the degradation of incretin hormone, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), and consequently prolong the physiologic effect of GLP-1, thereby exerting blood glucose-lowering effect through enhanced physiologically regulated insulin secretion. Interestingly, DPP-4 inhibitors are proposed to likely affect other peptides than GLP-1, since DPP-4 is a multifunctional enzyme and cleaves a number of other substrates than GLP-1, such as neuropeptide, cytokines, and chemokines [6]-[9]. Previous preclinical studies show that DPP4 inhibitors prevent cardiac diastolic dysfunction [10] and ameliorate glomerulopathy [11] in insulin-resistant Zucker obese rats, ameliorate vascular dysfunction in experimental sepsis [12], reduce myocardial infarct size in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion model [13], or reduce vascular endothelial oxidative stress [14]. However, it remains to be defined whether DPP-4 inhibitor can ameliorate cardiovascular injury beyond blood glucose control. Recent large clinical trials show that alogliptin [15] and saxagliptin [16] failed to reduce cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes, although the meta-analysis provides evidence that compared to other glucose-lowering therapies, DPP-4 inhibitors may possibly decrease cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes [7]. There is the possibility that the cardiovascular effects may differ among DPP-4 inhibitors.

Patients with type 2 diabetes often suffer from hypertension, particularly salt-sensitive hypertension. Importantly, salt-sensitive hypertension is associated with greater risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality than salt-resistant hypertension [17]-[21]. Therefore, it is of particular interest to examine whether DPP-4 inhibitor can mitigate cardiovascular injury in salt-sensitive hypertension. To test our hypothesis that DPP-4 inhibition can suppress cardiovascular injury induced by salt-sensitive hypertension, independently of glycemic control and blood pressure control, we examined the effect of linagliptin [22],[23], a DPP-4 inhibitor with unique xanthine-based structure, on cardiovascular injury in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats, a useful model of salt-sensitive hypertension. We obtained the evidence that initiation of linagliptin administration after onset of hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy limited cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, inflammation, and vascular dysfunction in salt-induced hypertension independently of blood glucose or blood pressure.

Methods

Animals

All procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals approved by Kumamoto University Graduate School of Medical Sciences. Male Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive (DS) rats were obtained from Japan SLC Inc (Shizuoka, Japan).

Experimental protocol

Eight % NaCl diet is known to cause severe hypertension and cardiovascular injury in DS rats, while less than 8% NaCl diet causes mild hypertension and mild cardiovascular injury in DS rats [24],[25]. Therefore, in the present study, 8% NaCl diet was used to make a model of salt-sensitive hypertension. DS rats started to be fed an 8% NaCl diet (high-salt diet) from 7 weeks of age, and oral administration of linagliptin to DS rats was initiated from 11-week-old age. Eleven-week-old DS rats with established hypertension and established cardiac hypertrophy, were randomized into two groups, and were orally given (1) vehicle or (2) linagliptin (3 mg/kg/day) by gastric gavage once a day for 4 weeks (until 15 weeks of age). DS rats fed 0.3% NaCl diet (normal-salt diet) were served as the control. After 4 weeks of the drug treatment, DS rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, arterial blood was immediately collected by cardiac puncture, and serum was collected by centrifugation and stored at −80°C until use. After perfusion with phosphate-buffered saline, the carotid artery, the thoracic aorta, and the heart were immediately excised for the measurement of various parameters, as described below. Left ventricular tissues were equally divided into three parts from apex to the base of heart; the apex, the middle, the base of heart. The real-time RT-PCR and western blot analysis was performed using the apex tissues. The Sirius red staining and immunohistochemistry were performed on paraffin embedded middle part. The DHE staining was performed on a series of cryostat sections of the base of heart.

Echocardiography

In vivo cardiac morphology was assessed by transthoracic echocardiography (12-MHz echocardiographic probe, PHILIPS SONOS-4500), as previously described [26]-[28]. In brief, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane. M-mode left ventricular (LV) end-systolic and end-diastolic diameters were averaged from 3–5 beats. M-mode tracings were recorded through left ventricular anterior and posterior walls at the papillary muscle level to measure left ventricular end-diastolic dimension, left ventricular end-systolic dimension, fractional shortening, left ventricular ejection fraction, left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end diastole, and inter ventricular septum wall thickness at end diastole. LV mass index was calculated as follows: LV mass =1.04 X [(LVDd + PWd + LVPw)3 – LVDd3], according to the previous report [29]. Studies and analysis were performed by investigators in a blinded fashion.

Vessel ring preparation and organ chamber experiments

Isometric tension was measured as previously described [30]. In brief, carotid artery from DS rats were cut into 5-mm rings with special care to preserve the endothelium, and they were then mounted in organ baths filled with modified Tyrode buffer (pH 7.4; NaCl 121 mmol/L, KCl 5.9 mmol/L, CaCl2 2.5 mmol/L, MgCl2 1.2 mmol/L, NaH2PO4 1.2 mmol/L,NaHCO3 15.5 mmol/L, and D-glucose 11.5 mmol/L) aerated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37°C. The preparations were attached to a force transducer, and isometric tension was recorded on a polygraph. A resting tension of 1 g was maintained throughout the experiment. Vessel rings were primed with KCl (50 mmol/L) and then precontracted with L-phenylephrine (10−7 mol/L). After the plateau of tension was attained, the rings were exposed to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (10−9 to 10−4 mol/l) or sodium nitroprusside (SNP) (10−9 to 10−4 mol/L) to obtain cumulative concentration response curves.

Measurement of blood pressure

Systolic blood pressure of conscious rats was periodically measured by tail-cuff plethysmography (BP-98A; Softron Co, Tokyo, Japan). To minimize chances for biasing of results, blood pressure measurement was performed by a technician who was blinded to the experimental groups [31]. The animals were acclimated to the measurement procedures and were prewarmed at 37°C for 20 minutes before measurement of blood pressure. Ten measurements per animal were averaged for determination of blood pressure.

Collection of urine samples in metabolic cages

At 1 week and 3 weeks after initiation of drug treatment, the above mentioned 3 groups of DS rats were acclimatized to the metabolic cages (Techniplast 3701 M001, Buguggiate, Italy) for 24 hours, then 24-hr urine was collected with metabolic cages to measure urine volume and urinary electrolyte excretions.

Western blot analysis

Our detailed method has been described previously [30]. Antibodies used were as follows: anti-p67phox (x5000, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), anti-p22phox (x2000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) (x2000, Abcam, Camgridge, UK). The intensity of the bands was quantified using NIH Image analysis software v1.61. In individual samples, each value was corrected for that of GAPDH.

Measurement of tissue superoxide

Hearts and aortas removed from DS rats were immediately frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT embedding medium (Sakura Finetek, Tokyo, Japan). Dihydroethidium (DHE) was used to evaluate tissue superoxide levels in situ, as described [32]. In brief, DHE fluorescence was visualized by fluorescence microscopy using an excitation wavelength of 520–540 nm and a rhodamine emission filter. DHE fluorescence of tissue was captured with the same exposure time (1.0 s), and it was quantified using Lumina Vision. The mean fluorescence was quantified and expressed relative to values obtained from control rats. We have previously verified that DHE fluorescence obtained by our method is indeed attributed to superoxide [33].

Histological examination and immunohistochemistry

Hearts were fixed in 4% (wt/vol.) paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with Sirius Red F3BA (0.5% wt/vol. in saturated aqueous picric acid; Aldrich Chemical Company, St Louis, MO, USA) for the measurement of collagen volume fraction. Cardiac interstitial fibrosis and the ratio of wall to lumen area of coronary artery were quantified, as described [34]. The positive area of fibrosis per field area was assessed by examining at least 10 fields per rat using Lumina Vision version 2.2 analysis software.

For ED-1 immunohistochemistry, cardiac sections were incubated overnight with ED1 antibody (×100; BMA Biomedicals, Switzerland) followed by Histofine simple stain Max-Po (M) (Nichirei, Biosciences, Tokyo, Japan). The number of cardiac ED-1-positive cells per mm2 was counted in a blinded manner by examining more than 10 fields per section using a microscope with X200 magnification. The average ED-1-positive cell number was obtained in each rat.

Measurement of left ventricular mRNA

MCP-1 mRNA expression was quantified using real-time PCR, as described previously [35]. TaqMan primers and probes for collagen I (Rn01526721_m1), collagen III (Rn01437681_m1) and GAPDH (Rn01775763_g1) were derived from the commercially available TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystem).

Measurement of DPP-4 activity, GLP-1, and insulin

Non-fasting serum glucose, insulin, and active GLP-1 concentrations were measured by the Glucose CII-Test (Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan), the Insulin ELISA kit (Morinaga Institute of Biological Science, Inc., Yokohama, Japan), and GLP-1, the Active form Assay Kit-IBL (Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Gunma, Japan), respectively. DPP4 activity was measured using DPP4-Glo Protease Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means ± SEM. The data on blood pressure were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures, followed by Fisher’s protected least squares difference (PLSD) test using Prism (Graph Pad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Other data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD test, in the case of comparison among three groups. In all tests, differences were considered statistically significant at a value of P < 0.05.

Results

Effects of linagliptin on blood pressure of DS rats fed high-salt diet

As shown in Figure 1, before initiation of linagliptin administration, DS rats fed high-salt diet for 4 weeks already developed hypertension (more than 170 mmHg). Initiation of linagliptin administration after onset of hypertension in high-salt-loaded DS rats did not significantly alter blood pressure of DS rats, throughout the treatment.

Effect of linagliptin on blood pressure of high salt-loaded DS rats at 1 week and 3 weeks after initiation of linagliptin treatment. Abbreviations used: Normal Na, normal salt-fed DS rats; Veh, vehicle-treated DS rats fed high-salt diet; Lin, linagliptin-treated DS rats fed high-salt diet. Each value represents mean ± SEM (n = 7 in Normal Na, n = 11 in Veh, n = 11 in Lin).

Effects of linagliptin on cardiac weight and echocardiographic parameters

As shown in Figure 2 (A), DS rats fed high-salt diet had greater left ventricular weight than those fed normal-salt diet (P < 0.01). Linagliptin treatment significantly reduced left ventricular weight of high-salt-loaded DS rats (P < 0.05). As shown in Figure 2(B)-(F), LV mass index, left ventricular posterior diastolic wall thickness (LVPw), interventricular septum diastolic wall thickness (IVSd), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVDd), and left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVDs) of high-salt-loaded DS rats were greater than those of normal-salt fed DS rats. Linagliptin treatment significantly reduced the increase in LV mass index (P < 0.05), LVPw (P < 0.01), IVSd (P < 0.01), LVDd (P < 0.05), and LVDs (P < 0.05) of high-salt-loaded DS rats. Fractional shortening (FS) in vehicle group of high-salt fed DS rats was smaller than that in normal-salt fed DS rats (P < 0.01), while there was no difference in FS between normal-salt fed DS rats and linagliptin group of high-salt fed DS rats.

Effect of linagliptin on cardiac weight (A) and echocardiographic parameters ((B)-(G))of high salt-loaded DS rats. Each value represents mean ± SEM (n = 7 in Normal Na, n = 11 in Veh, n = 11 in Lin). Abbreviation used are the same as in Figure 1. LV mass index, left ventricular mass index; IVSd, interventricular septum diastolic wall thickness; LVPw, left ventricular posterior diastolic wall thickness; LVDd, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVDs, left ventricular end-systolic diameter; FS, fractional shortening.

Effects of linagliptin on body weight and organ weights of DS rats fed high-salt diet

Linagliptin treatment decreased the increase in liver weight of high-salt loaded DS rats (P < 0.05) (Table 1). There was no significant difference between vehicle group and linagliptin group of high-salt-loaded DS rats, regarding body weight, lung weight, or kidney weight (Table 1).

Effects of linagliptin on cardiac fibrosis, inflammation, and coronary arterial remodeling of DS rats fed high-salt diet

As shown in Figure 3, high-salt-loaded DS rats exhibited greater cardiac interstitial fibrosis (P < 0.01), greater ED1-positive cell (macrophage) infiltration (P < 0.01), and greater ratio of wall to lumen of coronary artery (P < 0.01) than those fed normal-salt diet. Linagliptin treatment significantly reduced the increase in cardiac interstitial fibrosis (P < 0.01), cardiac ED1-positive cell number (P < 0.01), and ratio of wall to lumen of coronary artery (P < 0.05) in high-salt-loaded DS rats.

Effect of linagliptin on cardiac interstitial fibrosis (A), ED-1-positive cell numbers (B), and coronary arterial remodeling (C) of high salt-loaded DS rats. Each value represents mean ± SEM (n = 5-7 in Normal Na, n = 11 in Veh, n = 11 in Lin). Abbreviations used are the same as in Figure 1. Upper panels in (A), (B), and (C) indicate representative photomicrographs of cardiac sections stained with Sirius red, ED-1, and Sirius red, respectively.

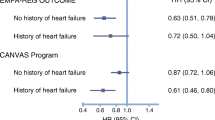

Effects of linagliptin on cardiac oxidative stress, p67phox, angiotensin-converting enzyme, and MCP-1 or collagen mRNA

As shown in Figure 4, linagliptin treatment significantly ameliorated the increase in cardiac superoxide (P < 0.01), cardiac NADPH oxidase subunit p67phox (P < 0.01), and cardiac ACE levels (P < 0.01) of high-salt loaded DS rats.

Effect of linagliptin on cardiac oxidative stress (A), p67phox(B), ACE (C), and MCP-1 mRNA (D) of high salt-loaded DS rats. Each value represents mean ± SEM (n = 7 in Normal Na, n = 11 in Veh, n = 11 in Lin). Abbreviations used are the same as in Figure 1. NS, not significant between groups. Upper panels in (A) indicate representative photomicrographs of cardiac sections stained with dihydroethidium. Upper panels in (B) and (C) indicate representative western blot of p67phox and ACE, respectively. In (D), MCP-1 mRNA levels in individual rats were corrected for GAPDH mRNA levels.

Linagliptin treatment tended to reduce cardiac MCP-1 mRNA levels in high-salt fed DS rats, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 4 (D)). Cardiac collagen I mRNA levels were 1.00 ± 0.22, 1.68 ± 0.23, and 1.35 ± 0.20 and cardiac collagen III mRNA levels were 1.00 ± 0.09, 2.18 ± 0.33, and 1.61 ± 0.17, in normal-salt fed DS rats, vehicle-treated high-salt fed DS rats, and linagliptin-treated high-salt fed rats, respectively. There was a trend for reduction of collagen I and collagen III mRNA levels by linagliptin, although the difference did not reach statistical significance.

Effects of linagliptin on vascular function and oxidative stress of DS rats

As shown in Figure 5, linagliptin significantly ameliorated the impairment of acetylcholine-induced vascular relaxation and that of SNP-induced vascular relaxation of high-salt loaded DS rats. As shown in Figure 5 (C), linagliptin reduced the increase in vascular superoxide of high-salt loaded DS rats (P < 0.01). Figure 5 (D) indicates that linagliptin significantly attenuated the increase in vascular p22phox in high-salt loaded DS rats (P < 0.05).

Effect of linagliptin on vascular relaxation induced by acetylcholine (A) and SNP (B), vascular superoxide (C), and vascular p22phox (D) of high salt-loaded DS rats. Each value represents mean ± SEM (n = 7 in Normal Na, n = 9-11 in Veh, n = 11 in Lin). Abbreviations used are the same as in Figure 1. NS, not significant between groups. Upper panels in (C) and (D) indicate representative photomicrographs of aortic sections stained with dihydroethidium and representative western blot bands, respectively.

Effects of linagliptin on non-fasting serum DPP-4 activity, GLP-1 concentrations, insulin, and glucose of DS rats

As shown in Figure 6, linagliptin significantly decreased non-fasting serum DPP-4 activity of DS rats by 67.7% (P < 0.01), which was accompanied by the significant increase in serum GLP-1 concentrations by 1.6-fold (P < 0.01) and the slight but significant increase in non-fasting serum insulin (P < 0.05). However, there was no difference in non-fasting blood glucose levels between normal-salt and high-salt fed DS rats, and linagliptin did not alter non-fasting blood glucose levels in high-salt fed DS rats.

Effect of linagliptin on serum DPP4 activity, GLP-1, insulin, and glucose levels of high salt-loaded DS rats. Each panel indicates relative DPP-4 activity (A), GLP-1 (B), serum insulin (C), and serum glucose (D). Abbreviations used are the same as in Figure 1. Each value represents mean ± SEM (n = 7 in Normal Na, n = 11 in Veh, n = 10 in Lin).

Effects of linagliptin on urine volume and urinary electrolytes

Table 2 indicates the data on 24-hour urine sample collected with metabolic cages at 1 and 3 weeks after initiation of linagliptin treatment. At both time points, high-salt loaded DS rats displayed greater urine volume and greater excretions of urinary sodium, chloride, and potassium than normal-salt-fed DS rats. Linagliptin did not significantly affect 24-hour urine volume and 24-hour excretions of urinary sodium, chloride, and potassium in high-salt loaded DS rats, throughout the treatment. Food intake and water intake in DS rats were not altered by linagliptin treatment, compared with vehicle treatment.

Discussion

The main purpose of this work was to determine whether initiation of DPP-4 inhibitor linagliptin administration after onset of hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy can exert direct beneficial effects on cardiovascular injury induced by salt-sensitive hypertension. To address this issue, in this work, we used DS rats which are a useful model of salt-sensitive hypertension and display insulin resistance and no fasting hyperglycemia [36]-[39]. Furthermore, we used linagliptin in the present study, because linagliptin has a unique xanthine-based structure and takes the advantage of being used in patients with renal dysfunction without dose adjustment in contrast to other approved DPP-4 inhibitors [22],[23]. Moreover, linagliptin significantly improves glycemic control and is well tolerated in patients with type 2 diabetes complicated by hypertension [40] and is hypothesized to have cardiovascular benefits in type 2 diabetic patients [41]. The major findings of this study were that linagliptin directly ameliorated cardiac hypertrophy, inflammation, and fibrosis, coronary arterial remodeling, and vascular endothelial dysfunction in salt-sensitive hypertensive rats, and these protective effects of linagliptin were associated with the attenuation of cardiac and vascular oxidative stress and cardiac ACE. Thus, our present work provides a novel insight into the mechanism underling cardiovascular protection by DPP-4 inhibition. Moreover, our present findings provide important clinical implications in the management of diabetes complicated with hypertension, since initiation of linagliptin administration after onset of hypertension was shown to protect against cardiovascular injury.

Type 2 diabetes and hypertension frequently coexist in the same patients. Importantly, hypertensive patients with coexisting diabetes are often characterized by salt-sensitive hypertension. Furthermore, salt-sensitive hypertension is shown to have greater risk for cardiovascular events than salt-resistant hypertension [17]-[21]. Therefore, any effects of DPP-4 inhibition on blood pressure and cardiovascular injury in the setting of salt-sensitive hypertension are of particular interest. However, the impact of DPP-4 inhibition on salt-sensitive hypertension remains to be defined. These encouraged us to investigate the effect of linagliptin on blood pressure and cardiovascular injury in salt-sensitive hypertensive rats. There has been uncertainty about the effect of DPP-4 inhibitors on blood pressure. It has been reported that DPP-4 inhibition significantly reduces blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) [42],[43] and very slightly lowers blood pressure in nondiabetic patients [44]. On the other hand, other studies show that DPP-4 inhibitor has no effect on blood pressure in renovascular hypertensive rats [45], increases blood pressure in SHR [46] and diminish hypotensive effects of high-dose of ACE inhibitor in subjects with metabolic syndrome [47]. Thus, the effect of DPP-4 inhibition on blood pressure appears to be dependent on type of hypertension or experimental conditions. In the present study, initiation of linagliptin administration after onset of hypertension did not significantly alter blood pressure of salt-sensitive hypertensive rats. Moreover, our data on 24-hr urine collected with metabolic cage indicated no significant alteration of urine volume and urinary sodium, chloride, and potassium excretions by linagliptin in DS rats, showing no significant natriuretic effects of linagliptin in DS rats. Collectively, our present work supported the notion that the protective effects of linagliptin against cardiovascular injury in DS rats were mediated by its direct pleiotrophic effects, independently of blood pressure.

Oxidative stress [48]-[50] and inflammation [51] play a key role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease, including cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling, vascular endothelial dysfunction, and atherosclerosis. Moreover, oxidative stress and inflammation are shown to be involved in cardiovascular injury in DS rats [27]. Of note, in the present study, linagliptin markedly attenuated oxidative stress in cardiac and vascular tissues of DS rats as shown by the reduction of cardiovascular superoxide. Furthermore, linagliptin significantly reduced cardiac macrophage infiltration in DS rats, as shown by the decrease in ED1-positive cell (a marker of macrophage) by linagliptin. Thus, the protective effects of linagliptin against cardiovascular injury in DS rats appear to be at least in part mediated by the significant decrease in cardiovascular oxidative stress and inflammation. Interestingly, linagliptin significantly reduced cardiac p67phox and vascular p22 phox of DS rats. p67phox and p22 phox are key subunits of NADPH oxidase generating superoxide [52]. Therefore, the attenuation of cardiovascular oxidative stress by linagliptin might be partially attributed to the reduction of p67phox or p22 phox.

A large number of clinical and experimental studies provide the solid evidence that ACE plays a central role in the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis and heart failure [1]. A subdepressor dose of ACE inhibitor administration significantly attenuates cardiac oxidative stress and improves cardiac function in DS rats without affecting blood pressure, indicating that cardiac ACE is involved in cardiac oxidative stress and cardiac dysfunction independently of blood pressure [53]-[55]. In fact, in clinical practice, ACE inhibitors are well established to be effective for treatment of cardiovascular disease in a broad range of high-risk patients including diabetic patients [1],[56]. There have been many reports showing that cardiac ACE plays a causal role in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling in DS rats [26],[53],[57]. In the present study, it is noteworthy that the increased cardiac ACE in DS rats was significantly reduced by linagliptin treatment. Collectively, the cardioprotective effects of linagliptin observed in this work seems to be at least in part mediated by the reduction of cardiac ACE.

In our present study, expectedly, linagliptin treatment of DS rats significantly reduced serum DPP-4 activity, being accompanied by the significant increase in circulating GLP-1. Despite the significant increase in serum GLP-1 and insulin by linagliptin, blood glucose levels were not significantly altered by linagliptin. No alteration of blood glucose by linagliptin is in good agreement with the previous findings that the significant improvement of insulin resistance by GLP-1 or GLP-1 receptor analogue in DS rats did not change blood glucose levels in DS rats [58], and seems to be explained by the fact that DS rats exhibit insulin resistance but no fasting hyperglycemia [36]-[39]. Importantly, the increase in circulating GLP-1 with DPP-4 inhibition is much smaller than that with exogenous GLP-1 administration. DPP-4 inhibitors are likely to affect other peptides than GLP-1, since DPP-4 is a multifunctional enzyme and can cleave a number of other substrates than GLP-1, and DPP-4 inhibitors are proposed to potentially confer cardiovascular protective effects through GLP-1- independent mechanism [6],[8],[59]-[61]. Interestingly, previous report [62] indicated that chronic infusion of exogenous GLP-1 significantly lowered blood pressure of DS rats through natriuresis, and these findings [62] are different from our present observations indicating no alteration of blood pressure and no increase in urinary sodium excretion by linagliptin in DS rats. Collectively, these findings support the notion that DPP-4 inhibitor potentially has different mode of action from GLP-1 or GLP-1 agonist and cardiovascular protective effect of linagliptin observed in this study might be partially mediated by GLP-1-independent mechanism. However, further study is needed to elucidate the precise mechanism underling the cardiovascular protective effects of linagliptin in salt-sensitive hypertension.

Study limitation

There are several study limitations in this study. First, as cardiac function of DS rats were investigated at the stage of no cardiac diastolic dysfunction (15 weeks of age), our present work did not allow us to determine whether linagliptin can finally improve cardiac diastolic dysfunction of DS rats. Previous study [10] investigating the preventive effect of linagliptin in insulin-resistant Zucker obese rats shows that linagliptin prevented the development of cardiac diastolic dysfunction despite no attenuation of cardiac oxidative stress, cardiac hypertrophy or fibrosis. Therefore, future study is required to elucidate the therapeutic effect of longer term administration of DPP4 inhibitor on cardiac diastolic dysfunction. Furthermore, in the present study, as the difference in echocardiographic parameters between the groups was small, more sensitive method such as hemodynamic study is needed to validate the improvement of cardiac function by linagliptin. Second, the present work provided no detailed mechanism underlying the attenuation of cardiac fibrosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress by linagliptin. Particularly, further analysis of oxidative stress marker is required to confirm the attenuation of oxidative stress by linagliptin. Third, it cannot be ruled out that the improvement of acetylcholine-induced vascular relaxation by linagliptin might be attributed to the improvement of vascular smooth muscle cell function rather than the improvement of endothelial function, since linagliptin also ameliorated the impairment of smooth muscle cell-dependent vascular relaxation. However, in vitro study shows that linagliptin specifically suppresses endothelial cell damage and reduce endothelial oxidative stress [14]. Finally, direct blood pressure measurement was not performed in the present study. Accordingly, it cannot be completely excluded that linagliptin might reduce blood pressure of DS rats to a small extent, although the tale-cuff method is a popular and established method for determination of blood pressure [31].

Conclusions

In conclusion, our work provided the evidence that DPP-4 inhibitor linagliptin protected against cardiovascular injury in salt-sensitive hypertensive rats, independently of blood glucose or blood pressure. These beneficial effects of linagliptin were associated with the attenuation of oxidative stress and cardiac ACE. Since linagliptin initiated after onset of hypertension was shown to exert positive therapeutic cardiovascular effects, our work highlights linagliptin as potentially a promising therapeutic agent for treatment of macrovascular disease in patients with coexisting diabetes and hypertension. However, further clinical trials investigating the effect of DPP-4 inhibition on cardiovascular outcome is required to define our proposal.

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

Angiotensin converting enzyme

- DPP-4:

-

Dipeptidylpeptidase-4

- DS rat:

-

Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats

- GLP-1:

-

Glucagon-like peptide-1

- LV:

-

Left ventricular

- SNP:

-

Sodium nitroprusside

References

Dzau VJ, Antman EM, Black HR, Hayes DL, Manson JE, Plutzky J, Popma JJ, Stevenson W: The cardiovascular disease continuum validated: clinical evidence of improved patient outcomes: part I: pathophysiology and clinical trial evidence (risk factors through stable coronary artery disease). Circulation. 2006, 114: 2850-2870. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655688.

Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, Goff DC, Bigger JT, Buse JB, Cushman WC, Genuth S, Ismail-Beigi F, Grimm RH, Probstfield JL, Simons-Morton DG, Friedewald WT: Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008, 358: 2545-2559. 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743.

Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA: 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008, 359: 1577-1589. 10.1056/NEJMoa0806470.

Singh A, Donnino R, Weintraub H, Schwartzbard A: Effect of strict glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus on frequency of macrovascular events. Am J Cardiol. 2013, 112: 1033-1038. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.05.044.

Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, Hadden D, Turner RC, Holman RR: Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000, 321: 405-412. 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405.

Panchapakesan U, Mather A, Pollock C: Role of GLP-1 and DPP-4 in diabetic nephropathy and cardiovascular disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2013, 124: 17-26. 10.1042/CS20120167.

Patil HR, Al Badarin FJ, Al Shami HA, Bhatti SK, Lavie CJ, Bell DS, O’Keefe JH: Meta-analysis of effect of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors on cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2012, 110: 826-833. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.04.061.

Russell-Jones D, Gough S: Recent advances in incretin-based therapies. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012, 77: 489-499. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04483.x.

Zhong J, Rao X, Rajagopalan S: An emerging role of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) beyond glucose control: potential implications in cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2013, 226: 305-314. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.09.012.

Aroor AR, Sowers JR, Bender SB, Nistala R, Garro M, Mugerfeld I, Hayden MR, Johnson MS, Salam M, Whaley-Connell A, Demarco VG: Dipeptidylpeptidase inhibition is associated with improvement in blood pressure and diastolic function in insulin-resistant male Zucker obese rats. Endocrinology. 2013, 154: 2501-2513. 10.1210/en.2013-1096.

Nistala R, Habibi J, Aroor A, Sowers JR, Hayden MR, Meuth A, Knight W, Hancock T, Klein T, DeMarco VG, Whaley-Connell A: DPP4 Inhibition attenuates filtration barrier injury and oxidant stress in the zucker obese rat. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014, 22: 2172-2179. 10.1002/oby.20833.

Kroller-Schon S, Knorr M, Hausding M, Oelze M, Schuff A, Schell R, Sudowe S, Scholz A, Daub S, Karbach S, Kossmann S, Gori T, Wenzel P, Schulz E, Grabbe S, Klein T, Munzel T, Daiber A: Glucose-independent improvement of vascular dysfunction in experimental sepsis by dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibition. Cardiovasc Res. 2012, 96: 140-149. 10.1093/cvr/cvs246.

Hausenloy DJ, Whittington HJ, Wynne AM, Begum SS, Theodorou L, Riksen N, Mocanu MM, Yellon DM: Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 reduce myocardial infarct size in a glucose-dependent manner. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013, 12: 154-10.1186/1475-2840-12-154.

Ishibashi Y, Matsui T, Maeda S, Higashimoto Y, Yamagishi S: Advanced glycation end products evoke endothelial cell damage by stimulating soluble dipeptidyl peptidase-4 production and its interaction with mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013, 12: 125-10.1186/1475-2840-12-125.

White WB, Cannon CP, Heller SR, Nissen SE, Bergenstal RM, Bakris GL, Perez AT, Fleck PR, Mehta CR, Kupfer S, Wilson C, Cushman WC, Zannad F, Investigators E: Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013, 369: 1327-1335. 10.1056/NEJMoa1305889.

Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, Steg PG, Davidson J, Hirshberg B, Ohman P, Frederich R, Wiviott SD, Hoffman EB, Cavender MA, Udell JA, Desai NR, Mosenzon O, McGuire DK, Ray KK, Leiter LA, Raz I: Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2013, 369: 1317-1326. 10.1056/NEJMoa1307684.

He J, Ogden LG, Vupputuri S, Bazzano LA, Loria C, Whelton PK: Dietary sodium intake and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease in overweight adults. Jama. 1999, 282: 2027-2034. 10.1001/jama.282.21.2027.

Meneton P, Jeunemaitre X, de Wardener HE, MacGregor GA: Links between dietary salt intake, renal salt handling, blood pressure, and cardiovascular diseases. Physiol Rev. 2005, 85: 679-715. 10.1152/physrev.00056.2003.

Morimoto A, Uzu T, Fujii T, Nishimura M, Kuroda S, Nakamura S, Inenaga T, Kimura G: Sodium sensitivity and cardiovascular events in patients with essential hypertension. Lancet. 1997, 350: 1734-1737. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)05189-1.

Perry IJ, Beevers DG: Salt intake and stroke: a possible direct effect. J Hum Hypertens. 1992, 6: 23-25.

Weinberger MH, Fineberg NS, Fineberg SE, Weinberger M: Salt sensitivity, pulse pressure, and death in normal and hypertensive humans. Hypertension. 2001, 37: 429-432. 10.1161/01.HYP.37.2.429.

Doupis J: Linagliptin: from bench to bedside. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014, 8: 431-446. 10.2147/DDDT.S59523.

Gallwitz B: Emerging DPP-4 inhibitors: focus on linagliptin for type 2 diabetes. Diab Metab Syndr Obes. 2013, 6: 1-9. 10.2147/DMSO.S23166.

Dahl LK, Knudsen KD, Heine MA, Leitl GJ: Effects of chronic excess salt ingestion. modification of experimental hypertension in the rat by variations in the diet. Circ Res. 1968, 22: 11-18. 10.1161/01.RES.22.1.11.

Pfeffer MA, Pfeffer J, Mirsky I, Iwai J: Cardiac hypertrophy and performance of Dahl hypertensive rats on graded salt diets. Hypertension. 1984, 6: 475-481. 10.1161/01.HYP.6.4.475.

Kim S, Yoshiyama M, Izumi Y, Kawano H, Kimoto M, Zhan Y, Iwao H: Effects of combination of ACE inhibitor and angiotensin receptor blocker on cardiac remodeling, cardiac function, and survival in rat heart failure. Circulation. 2001, 103: 148-154. 10.1161/01.CIR.103.1.148.

Yamamoto E, Kataoka K, Yamashita T, Tokutomi Y, Dong YF, Matsuba S, Ogawa H, Kim-Mitsuyama S: Role of xanthine oxidoreductase in the reversal of diastolic heart failure by candesartan in the salt-sensitive hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 2007, 50: 657-662. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.095315.

Yamamoto E, Lai ZF, Yamashita T, Tanaka T, Kataoka K, Tokutomi Y, Ito T, Ogawa H, Kim-Mitsuyama S: Enhancement of cardiac oxidative stress by tachycardia and its critical role in cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. J Hypertens. 2006, 24: 2057-2069. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000244956.47114.c1.

Pawlush DG, Moore RL, Musch TI, Davidson WR: Echocardiographic evaluation of size, function, and mass of normal and ypertrophied rat ventricles. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1993, 74: 2598-2605.

Nakamura T, Yamamoto E, Kataoka K, Yamashita T, Tokutomi Y, Dong YF, Matsuba S, Ogawa H, Kim-Mitsuyama S: Beneficial effects of pioglitazone on hypertensive cardiovascular injury are enhanced by combination with candesartan. Hypertension. 2008, 51: 296-301. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099044.

Kurtz TW, Griffin KA, Bidani AK, Davisson RL, Hall JE: Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals. Part 2: Blood pressure measurement in experimental animals: a statement for professionals from the subcommittee of professional and public education of the American Heart Association council on high blood pressure research. Hypertension. 2005, 45: 299-310. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150857.39919.cb.

Yamamoto E, Yamashita T, Tanaka T, Kataoka K, Tokutomi Y, Lai ZF, Dong YF, Matsuba S, Ogawa H, Kim-Mitsuyama S: Pravastatin enhances beneficial effects of olmesartan on vascular injury of salt-sensitive hypertensive rats, via pleiotropic effects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007, 27: 556-563. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000254855.24394.f9.

Kataoka K, Tokutomi Y, Yamamoto E, Nakamura T, Fukuda M, Dong YF, Ichijo H, Ogawa H, Kim-Mitsuyama S: Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 deficiency eliminates cardiovascular injuries induced by high-salt diet. J Hypertens. 2011, 29: 76-84. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833fc8b0.

Katayama T, Sueta D, Kataoka K, Hasegawa Y, Koibuchi N, Toyama K, Uekawa K, Mingjie M, Nakagawa T, Maeda M, Ogawa H, Kim-Mitsuyama S: Long-term renal denervation normalizes disrupted blood pressure circadian rhythm and ameliorates cardiovascular injury in a rat model of metabolic syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013, 2: e000197-10.1161/JAHA.113.000197.

Nakamura T, Fukuda M, Kataoka K, Nako H, Tokutomi Y, Dong YF, Yamamoto E, Yasuda O, Ogawa H, Kim-Mitsuyama S: Eplerenone potentiates protective effects of amlodipine against cardiovascular injury in salt-sensitive hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res. 2011, 34: 817-824. 10.1038/hr.2011.35.

Kotchen TA, Zhang HY, Covelli M, Blehschmidt N: Insulin resistance and blood pressure in Dahl rats and in one-kidney, one-clip hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1991, 261: E692-E697.

Ogihara T, Asano T, Ando K, Sakoda H, Anai M, Shojima N, Ono H, Onishi Y, Fujishiro M, Abe M, Fukushima Y, Kikuchi M, Fujita T: High-salt diet enhances insulin signaling and induces insulin resistance in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension. 2002, 40: 83-89. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000022880.45113.C9.

Reaven GM, Twersky J, Chang H: Abnormalities of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in Dahl rats. Hypertension. 1991, 18: 630-635. 10.1161/01.HYP.18.5.630.

Shehata MF: Genetic and dietary salt contributors to insulin resistance in Dahl salt-sensitive (S) rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2008, 7: 7-10.1186/1475-2840-7-7.

von Eynatten M, Gong Y, Emser A, Woerle HJ: Efficacy and safety of linagliptin in type 2 diabetes subjects at high risk for renal and cardiovascular disease: a pooled analysis of six phase III clinical trials. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013, 12: 60-10.1186/1475-2840-12-60.

Johansen OE, Neubacher D, von Eynatten M, Patel S, Woerle HJ: Cardiovascular safety with linagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pre-specified, prospective, and adjudicated meta-analysis of a phase 3 programme. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012, 11: 3-10.1186/1475-2840-11-3.

Liu L, Liu J, Wong WT, Tian XY, Lau CW, Wang YX, Xu G, Pu Y, Zhu Z, Xu A, Lam KS, Chen ZY, Ng CF, Yao X, Huang Y: Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor sitagliptin protects endothelial function in hypertension through a glucagon-like peptide 1-dependent mechanism. Hypertension. 2012, 60: 833-841. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.195115.

Pacheco BP, Crajoinas RO, Couto GK, Davel AP, Lessa LM, Rossoni LV, Girardi AC: Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibition attenuates blood pressure rising in young spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2011, 29: 520-528. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328341939d.

Mistry GC, Maes AL, Lasseter KC, Davies MJ, Gottesdiener KM, Wagner JA, Herman GA: Effect of sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, on blood pressure in nondiabetic patients with mild to moderate hypertension. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008, 48: 592-598. 10.1177/0091270008316885.

Chaykovska L, Alter ML, von Websky K, Hohmann M, Tsuprykov O, Reichetzeder C, Kutil B, Kraft R, Klein T, Hocher B: Effects of telmisartan and linagliptin when used in combination on blood pressure and oxidative stress in rats with 2-kidney-1-clip hypertension. J Hypertens. 2013, 31: 2290-2298. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283649b4d. discussion 2299

Jackson EK, Dubinion JH, Mi Z: Effects of dipeptidyl peptidase iv inhibition on arterial blood pressure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008, 35: 29-34. 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04737.x.

Marney A, Kunchakarra S, Byrne L, Brown NJ: Interactive hemodynamic effects of dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibition and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in humans. Hypertension. 2010, 56: 728-733. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.156554.

Forstermann U, Munzel T: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular disease: from marvel to menace. Circulation. 2006, 113: 1708-1714. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.602532.

Griendling KK, Sorescu D, Ushio-Fukai M: NAD(P)H oxidase: role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ Res. 2000, 86: 494-501. 10.1161/01.RES.86.5.494.

Takimoto E, Kass DA: Role of oxidative stress in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. Hypertension. 2007, 49: 241-248. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000254415.31362.a7.

Nicoletti A, Michel JB: Cardiac fibrosis and inflammation: interaction with hemodynamic and hormonal factors. Cardiovasc Res. 1999, 41: 532-543. 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00305-8.

Feng D, Yang C, Geurts AM, Kurth T, Liang M, Lazar J, Mattson DL, O’Connor PM, Cowley AW: Increased expression of NAD(P)H oxidase subunit p67(phox) in the renal medulla contributes to excess oxidative stress and salt-sensitive hypertension. Cell Metab. 2012, 15: 201-208. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.003.

Sakata Y, Yamamoto K, Mano T, Nishikawa N, Yoshida J, Miwa T, Hori M, Masuyama T: Temocapril prevents transition to diastolic heart failure in rats even if initiated after appearance of LV hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res. 2003, 57: 757-765. 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00722-8.

Takenaka H, Kihara Y, Iwanaga Y, Onozawa Y, Toyokuni S, Kita T: Angiotensin II, oxidative stress, and extracellular matrix degradation during transition to LV failure in rats with hypertension. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006, 41: 989-997. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.07.019.

Yamamoto K, Mano T, Yoshida J, Sakata Y, Nishikawa N, Nishio M, Ohtani T, Hori M, Miwa T, Masuyama T: ACE inhibitor and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker differently regulate ventricular fibrosis in hypertensive diastolic heart failure. J Hypertens. 2005, 23: 393-400. 10.1097/00004872-200502000-00022.

Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G: Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. the heart outcomes prevention evaluation study investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000, 342: 145-153. 10.1056/NEJM200001203420301.

Liang B, Leenen FH: Prevention of salt induced hypertension and fibrosis by angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in Dahl S rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2007, 152: 903-914. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707472.

Liu Q, Adams L, Broyde A, Fernandez R, Baron AD, Parkes DG: The exenatide analogue AC3174 attenuates hypertension, insulin resistance, and renal dysfunction in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2010, 9: 32-10.1186/1475-2840-9-32.

Avogaro A, Vigili De Kreutzenberg S, Fadini GP: Cardiovascular actions of GLP-1 and incretin-based pharmacotherapy. Curr Diab Rep. 2014, 14: 483-10.1007/s11892-014-0483-3.

Ban K, Noyan-Ashraf MH, Hoefer J, Bolz SS, Drucker DJ, Husain M: Cardioprotective and vasodilatory actions of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor are mediated through both glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor-dependent and -independent pathways. Circulation. 2008, 117: 2340-2350. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739938.

Dicembrini I, Pala L, Rotella CM: From theory to clinical practice in the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors therapy. Exp Diabetes Res. 2011, 2011: 898913-10.1155/2011/898913.

Yu M, Moreno C, Hoagland KM, Dahly A, Ditter K, Mistry M, Roman RJ: Antihypertensive effect of glucagon-like peptide 1 in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. J Hypertens. 2003, 21: 1125-1135. 10.1097/00004872-200306000-00012.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by a grant from Boehringer Ingelheim.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

S. K-M received lecture fees and research grant from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis, Sionogi, Takeda, Kyowa Hakko Kirin.

Authors’ contributions

Participated in research design: NK, and SK-M; conducted experiments: NK, YH, TK, KT, KU, DS, HK, MM, TN, and BL; all authors performed data analysis and interpretation; NK and SK-M contributed to the writing of the manuscript and critically revised the manuscript: all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Koibuchi, N., Hasegawa, Y., Katayama, T. et al. DPP-4 inhibitor linagliptin ameliorates cardiovascular injury in salt-sensitive hypertensive rats independently of blood glucose and blood pressure. Cardiovasc Diabetol 13, 157 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-014-0157-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-014-0157-0