Abstract

Background

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and receptor RAGE interaction play a role in diabetic vascular complications. Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) is a potential therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes. However, the role of DPP-4 in AGE-induced endothelial cell (EC) damage remains unclear.

Methods

In this study, we investigated the effects of DPP-4 on reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and RAGE gene expression in ECs. We further examined whether an inhibitor of DPP-4, linagliptin inhibited AGE-induced soluble DPP-4 production, ROS generation, RAGE, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) gene expression in ECs.

Results

DPP-4 dose-dependently increased ROS generation and RAGE gene expression in ECs, which were prevented by linagliptin. Mannose 6-phosphate (M6P) and antibodies (Ab) raised against M6P/insulin-like growth factor II receptor (M6P/IGF-IIR) completely blocked the ROS generation in DPP-4-exposed ECs, whereas surface plasmon resonance revealed that DPP-4 bound to M6P/IGF-IIR at the dissociation constant of 3.59 x 10-5 M. AGEs or hydrogen peroxide increased soluble DPP-4 production by ECs, which was prevented by N-acetylcysteine, RAGE-Ab or linagliptin. Linagliptin significantly inhibited the AGE-induced ROS generation, RAGE, ICAM-1 and PAI-1 gene expression in ECs.

Conclusions

The present study suggests that AGE-RAGE-induced ROS generation stimulates the release of DPP-4 from ECs, which could in turn act on ECs directly via the interaction with M6P/IGF-IIR, further potentiating the deleterious effects of AGEs. The blockade by linagliptin of positive feedback loop between AGE-RAGE axis and DPP-4 might be a novel therapeutic target for vascular injury in diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The pathological role of the non-enzymatic modification of amino groups of proteins, nucleic acids and lipids by reducing sugars such as glucose, a process that is also known as “Maillard reaction”, has become increasingly evident in various types of diseases [1–3]. It is now well established that early glycation products undergo further progressive modification over time in vivo to the formation of irreversibly cross-linked senescent macroprotein derivatives termed “advanced glycation end products (AGEs)” [1–3]. The formation and accumulation of AGEs in various tissues have been known to progress at a physiological aging and at an accelerated rate under hyperglycemic conditions [1–3]. There is accumulating evidence that AGEs elicit oxidative stress generation and subsequently evoke inflammatory and thrombogenic reactions in a variety of cells through the interaction with the receptor for AGEs (RAGE), thereby being involved in vascular complications in diabetes [4–9].

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), also known as CD26, is a type II transmembrane glycoprotein expressed on various cell types with multifunctional properties [10, 11]. DPP-4 not only plays a role in T cell activation and proliferation, but also modulates the physiological activity of many regulatory peptides, because it is involved in the cleavage of N-terminal amino acids from several chemokines and neuropeptides [10, 11]. Incretins such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptides (GIP) are gut hormones secreted from L and K cells in the intestine in response to food intake, respectively [12, 13], both of which are target proteins of DPP-4 and rapidly degraded and inactivated by this proteolytic enzyme [10, 11]. Since GLP-1 and GIP augment glucose-induced insulin release from pancreatic b-cells, suppresses glucagon secretion, and slows gastric emptying [12, 13], inhibition of DPP-4 has been proposed as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. However, it remains unclear DPP-4 inhibition could have beneficial effects on AGE-exposed endothelial cells (ECs). In other words, whether DPP-4 itself is involved in vascular injury in diabetes remains unknown. DPP-4 and D-Mannose-6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor (M6P/IGF-IIR) interaction contributes to T cell activation [14]. Therefore, in this study, we first investigated whether DPP-4 could directly act on human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) to stimulate reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and RAGE gene induction via the interaction with M6P/IGF-IIR. We next examined the effects of AGEs on soluble DPP-4 production released from HUVECs. We further studied whether an inhibitor of DPP-4, linagliptin inhibited the AGE-induced soluble DPP-4 production, ROS generation, RAGE, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) gene expression in HUVECs.

Methods

Materials

An inhibitor of DPP-4, linagliptin was generously gifted from Boehringer Ingelheim (Ingelheim, Germany). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) (essentially fatty acid free and essentially globulin free, lyophilized powder), D-Mannose-6-phosphate (M6P) and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). D-glyceraldehyde from Nakalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). Recombinant human DPP-4 from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) from Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Antibody (Ab) directed against human M6P/insulin-like growth factor II receptor (IGF-IIR) (M6P/IGF-IIR-Ab) and DPP-4 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Delaware, CA, USA).

Cells

HUVECs were cultured in endothelial basal medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum, 0.4% bovine brain extracts, 10 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor and 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone according to the supplier’s instructions (Clonetics Corp., San Diego, CA). DPP-4 or AGE treatment was carried out in a medium lacking epidermal growth factor and hydrocortisone.

Dihydroethidium (DHE) staining

HUVEC were treated with or without the indicated concentrations of DPP-4, 100 μg/ml AGE-BSA or 100 μg/ml non-glycated BSA in the presence or absence of 50 μM M6P, 5 μg/ml M6P/IGF-IIR-Ab, 10 nM or 0.5 μM linagliptin for 4 hr, and then the cells were incubated with phenol red free Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium containing 3 μM DHE (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR, USA). After 15 minutes, the cells were imaged under a laser-scanning confocal microscope. Superoxide generation was evaluated by intensity of DHE staining. The intensity was analyzed by microcomputer-assisted NIH image.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

Recombinant human IGF-IIR (100 μg/ml, R&D system) was immobilized via the amino groups to CM5 sensor chip (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) with the aid of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide and N-hydroxysuccinimide. For affinity measurements, the association and dissociation phases were monitored in a BIAcore 1000 (GE Healthcare). Recombinant human DPP-4 was injected into the flow cell at concentrations of 0.1 and 0.3 μM at a flow rate of 10 μl/min at 25°C. The sensor chip was regenerated with pulses of 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 6 M urea to the baseline level, followed by an extensive washing with the running buffer. Control experiments were performed with IGF-IIR-free channel on the same sensor chip. From the assay curves obtained, the control signals, reflecting the bulk effect of buffer, were subtracted using BIA-evaluation 4.1 software (GE Healthcare). Equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) was determined using the equation for 1:1 Langmuir binding.

Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reactions (RT-PCR)

HUVEC were treated with or without the indicated concentrations of DPP-4, 100 μg/ml AGE-BSA or 100 μg/ml non-glycated BSA in the presence or absence of 10 nM or 0.5 μM linagliptin for 4 hr. Then total RNA was extracted with RNAqueous-4PCR kit (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed using Assay-on-Demand and TaqMan 5 fluorogenic nuclease chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA) according to the supplier’s recommendation. IDs of primers for human RAGE, ICAM-1, PAI-1, β-actin and 18S gene were Hs00153957_m1, Hs00164932_m1, Hs01126606_m1, Hs99999903_m1, and Hs99999901_s1, respectively.

Preparation of AGE-BSA

AGE-BSA was prepared as described previously [15]. In brief, BSA (25 mg/ml) was incubated under sterile conditions with 0.1 M glyceraldehyde in 0.2 M NaPO4 buffer (pH 7.4) for 7 days. Then unincorporated sugars were removed by PD-10 column chromatography and dialysis against phosphate-buffered saline. Control non-glycated BSA was incubated in the same conditions except for the absence of reducing sugars. Preparations were tested for endotoxin using Endospecy ES-20S system (Seikagaku Co., Tokyo, Japan); no endotoxin was detectable.

Preparation of Ab raised against RAGE (RAGE-Ab)

Ab directed against human RAGE was prepared as described previously [16].

Soluble DPP-4 production

HUVECs were treated with or without 100 μg/ml AGE-BSA, 100 μg/ml non-glycated BSA or the indicated concentrations of H2O2 in the presence or absence of 1 mM NAC, 5 μg/ml RAGE-Ab or 10 nM linagliptin for 24 hr. Conditioned medium were collected and concentrated 20-fold using an Amicon ultrafiltration system (5000-kDa cutoff, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the method described previously [16]. Then 20 μg proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes as described previously [17]. Membranes were probed with Ab directed against human DPP-4, and then immune complexes were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Bioscience, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, all values were presented as means ± SE from at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed by one-way ANOVA followed by the Scheffe F test for multiple comparisons, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with the use of the PASW Statistics system (version 18.0; IBM Corporation, New York, NY, USA).

Results

We first examined the effects of DPP-4 on ROS generation in HUVECs. As shown in Figure 1A and 1B, DPP-4 dose-dependently increased superoxide generation in HUVECs; 500 ng/ml DPP-4-induced increase in ROS generation was completely blocked by the treatment with 10 nM linagliptin, 50 μM M6P or 5 μg/ml M6P/IGF-IIR-Ab. M6P or M6P/IGF-IIR alone did not affect superoxide generation in HUVECs. Figure 1C shows the representative binding sensorgram of 0.1 and 0.3 μM DPP-4 to immobilized M6P/IGF-IIR. SPR analysis revealed that DPP-4 bound to M6P/IGF-IIR; KD value was 3.59 × 10-5 ± 1.35 × 10-5 M. Furthermore, DPP-4 dose-dependently RAGE gene expression in HUVECs, which was also blocked by linagliptin (Figure 1D).

Effects of DPP-4 on ROS generation (A and B) and RAGE gene expression (D) in HUVECs and (C) representative binding sensorgram of DPP-4 to immobilized M6P/IGF-IIR. HUVEC were treated with or without the indicated concentrations of DPP-4 in the presence or absence of 50 μM M6P, 5 μg/ml M6P/IGF-IIR-Ab, or 10 nM linagliptin for 4 hr. (A and B) Then the cells were incubated with DHE. Upper panel shows typical microphotographs of the cells. Lower panel shows quantitative data of ROS generation evaluated by fluorescent intensity. (A) N = 12 per group. (B) N = 27 per group. (D) Total RNAs were transcribed and amplified by real-time PCR. Data were normalized by the intensity of β-actin mRNA-derived signals and then related to the value obtained with control. N = 3 per group. (C) DPP-4 at 0.1 and 0.3 μM was injected on the sensor chip immobilized M6P/IGF-IIR. N = 3 per group. * and **, p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 compared to the value with control, respectively.

We next examined whether AGEs could stimulate soluble DPP-4 generation by HUVECs. As shown in Figure 2A, AGEs increased DPP-4 production released from HUVECs, which was significantly prevented by the treatment with an anti-oxidant, NAC, RAGE-Ab or linagliptin. Moreover, H2O2 dose-dependently stimulated the release of DPP-4 from HUVECs (Figure 2B).

Effects of AGEs on DPP-4 production released from HUVECs. HUVECs were treated with or without 100 μg/ml AGE-BSA, 100 μg/ml non-glycated BSA or the indicated concentrations of H2O2 in the presence or absence of 1 mM NAC, 5 μg/ml RAGE-Ab or 10 nM linagliptin for 24 hr. Conditioned medium were collected and concentrated 20-fold using an Amicon ultrafiltration system. Then 20 μg proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Soluble DPP-4 expression released from the cells was measured. Each upper panel shows the representative bands. Lower panel shows the quantitative data. (A) N = 3 per group. (B) N = 9 per group.

We further investigated the effects of linagliptin on AGE-exposed HUVEC. As shown in Figure 3, AGEs stimulated superoxide generation and up-regulated m RNA levels of RAGE, ICAM-1 and PAI-1 in HUVECs, all of which were significantly blocked by linagliptin.

Effects of linagliptin on AGE-exposed HUVECs. HUVECs were treated with 100 μg/ml AGE-BSA or non-glycated BSA in the presence or absence of 10 nM or 0.5 μM linagliptin for 4 hr. (A) Cells were incubated with DHE. Upper panel shows typical microphotographs of the cells. Lower panel shows quantitative data of ROS generation evaluated by fluorescent intensity. N = 50 per group. (B-D) Total RNAs were transcribed and amplified by real-time PCR. Data were normalized by the intensity of β-actin (B) or 18S mRNA-derived signals (C and D) and then related to the value obtained with non-glycated BSA. (B) N = 15 per group. (B) N = 15 per group. (C and D) N = 9 per group. * and **, p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 compared to the value with AGEs alone, respectively.

Discussion

Role of DPP-4 in vascular injury

M6P/IGF-IIR has been shown to work as a receptor for DPP-4 in HUVECs and mediates its biological action, resultantly promoting transendothelial T cell migration, and an effect requires the enzymatic activity of DPP-4 [18]. In this study, we found for the first time that blocking the interaction of DPP-4 with M6P/IGF-IIR by the addition of excess amount of free M6P or M6P/IGF-IIR-Ab completely inhibited the DPP-4-induced increase in superoxide generation in HUVECs. Further, SPR analysis revealed that DPP-4 actually bound to M6P/IGF-IIR, and an inhibitor of DPP-4, linagliptin completely prevented the ROS generation and up-regulation of RAGE mRNA levels in DPP-4-exposed HUVECs. Since we have previously shown that AGEs stimulate RAGE gene expression in ECs via ROS generation [15], our present observations suggest that DPP-4 could increase ROS generation and subsequently RAGE gene overexpression in HUVECs through the interaction with M6P/IGF-IIR, whose ability is totally dependent on its intrinsic DPP-4 enzymatic activity. AGEs have been shown to impair the migration, adhesion and secretion potentials of late endothelial progenitor cells [19, 20]. Further, AGE-RAGE interaction causes inflammation and thrombogenesis in diabetic vessels [21, 22]. Therefore, given the atherosclerosis-promoting properties of AGE-RAGE axis, although the reason why DPP-4 caused vascular damage in diabetes remains unclear, DPP-4 itself might be involved in diabetic vascular injury. DPP-4 has been reported to not only stimulate proliferation of human coronary artery smooth muscle cells [23], but also contribute to monocyte migration, macrophage-mediated inflammatory reactions and tissue remodeling [24, 25], thus supporting the speculation that DPP-4 itself might work as a risk factor for atherosclerosis.

Crosstalk between AGE-RAGE axis and DPP-4

In this study, AGEs stimulated the release of DPP-4 from HUVECs, which was significantly inhibited by the treatment with an anti-oxidant, NAC, RAGE-Ab, or linagliptin. Moreover, H2O2 dose-dependently increased the production of soluble DPP-4 by HUVECs. So, the AGE-RAGE-induced ROS generation could be involved in soluble DPP-4 generation by HUVECs. The present findings have extended our previous observations [17] showing that serum levels of AGEs were independently correlated with circulating DPP-4 values in 432 consecutive outpatients and that AGEs significantly increase soluble DPP-4 release from cultured proximal tubular cells, one of the major cell types that expressed DPP-4 in humans [26]. Since we previously reported that AGEs at 100 μg/ml for 4 hr did not affect DPP-4 mRNA levels in HUVECs [27], the AGE-RAGE interaction might promote the proteolytic cleavage of membrane-bound DPP-4 from HUVECs via superoxide generation. Serum levels of AGEs are positively rather than inversely associated with soluble form of RAGE (sRAGE) (endogenous secretory RAGE plus cleaved RAGE) in both diabetic and non-diabetic subjects [28, 29]. Therefore, although exogenously administered sRAGE was shown to block the harmful effects of AGEs in animals by acting as a decoy receptor, it is questionable that sRAGE in humans could also exert the same biological effect, because its serum concentration is 1000 times lower than needed for efficiently capturing and eliminating the circulating AGEs [30]. Moreover, engagement of RAGE with its ligand has been shown to promote the RAGE shedding [30, 31]. These findings suggest that sRAGE level could reflect tissue RAGE expression and that AGEs might enhance the cleavage of DPP-4 from the cell membrane. Given the facts that serum DPP-4 activity is largely associated with circulating DPP-4 levels [10, 32] and that 20% of incretins derived from gastrointestinal tract are still alive in the blood pool [33, 34], cumulative hyperglycemia and resultant AGE accumulation might impair the incretins’ effects via elevation of circulating DPP-4 levels, further deteriorating glycemic control and thereby forming a vicious cycle in diabetic subjects. This scenario could support the clinical relevance of blockade of the pathological crosstalk between AGE-RAGE axis and DPP-4 by linagliptin in the treatment with type 2 diabetes.

Protective role of linagliptin against AGE-RAGE-induced vascular damage in diabetes

In the present study, we found that linagliptin significantly inhibited the AGE-induced ROS generation, RAGE, ICAM-1 and PAI-1 gene expression in HUVECs. AGEs are reported to up-regulate RAGE gene expression in a variety of cells via ROS generation and induce activation of redox-sensitive transcriptional factor, NF-kB and subsequent ICAM-1 and PAI-1 gene induction [7, 15, 31, 35–37]. Therefore, the AGE-RAGE-induced oxidative stress generation could further potentiate the harmful effects of AGEs via RAGE overexpression. So, linagliptin might inhibit the AGE-evoked inflammatory and thrombogenic responses in HUVECs by blocking the positive feedback loops between ROS generation and RAGE gene up-regulation. In this study, we could not clarify the mechanism by which linagliptin inhibited the AGE-induced ROS generation in HUVECs. However, we have previously shown that GLP-1 and GIP protect against AGE-induced HUVEC damage via anti-oxidative properties through the elevation of cyclic AMP, whose effect is augmented by the addition of DPP-4 inhibitor [27, 38, 39]. Since AGE-RAGE axis evokes ROS generation in ECs via NADPH oxidase activity, which is blocked by cAMP-elevating agents [6, 7, 15, 40], linagliptin could enhance the beneficial effects of incretins on AGE-exposed HUVECs by inhibiting NADPH oxidase activity. Furthermore, we have recently found that linagliptin contains xanthine scaffold structure, which could inhibit xanthine oxidase activity in vitro[41]. The anti-oxidative unique properties of this drug might also be involved in the blockade of vicious cycle between ROS generation and RAGE gene induction. It is unlikely that linagliptin directly inhibited the AGE-RAGE interaction because highly sensitive 27-MHz quartz crystal microbalance analysis (Affinix Q; Initium, Tokyo, Japan) revealed that linagliptin can not bind to AGEs in vitro (data not shown).

One early phase of atherosclerosis involves the recruitment and firm adhesion of inflammatory cells to ECs, whose process is mediated by adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 [42, 43]. Further, attenuated fibrinolytic activity due to increased PAI-1 levels is prevalent in diabetic patients, thus contributing to the increased risk of atherothrombosis in these subjects [37, 44, 45]. Linagliptin may be a promising strategy for not only ameliorating hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetic patients, but also protecting against vascular injury by suppressing ICAM-1 and PAI-1 expression through blockade of the deleterious effects of AGE-RAGE axis partly via inhibition of DPP-4 and M6P/IGF-IIR interaction. In pre-specified meta-analysis of cardiovascular events in linagliptin or comparator-treated patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, the hazard ratio for a composite of cardiovascular death, stroke, myocardial infarction, and hospitalization for unstable angina showed significantly lower risk with linagliptin than comparator [46]. Moreover, we have very recently found that DPP-4 inhibitor alogliptin treatment blocks the AGE-RAGE axis and resultantly reduces albuminuria in type 2 diabetes patients [47]. Fluorescent AGE levels have also been shown to be an independent marker of post-infarction heart failure development risk [48]. These data reinforce the important clinical implications of the present findings of linagliptin.

The peak plasma concentration of linagliptin after administration of single oral dose of 5 mg is reported to be about 10 nM [49]. So, the concentration of linagliptin having beneficial effects on HUVECs used in the present experiments (10 nM) may also be comparable to the therapeutic level which is achieved in the treatment for patients with type 2 diabetes.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations that should be noted. First, we did not examine here the effect of M6P/IGF-IIR-Ab on the increase in ROS generation induced by AGEs or the increase in RAGE gene expression induced by DPP-4 and AGEs. Second, although mRNA levels of DPP-4 were not changed by the treatment with AGEs, the effect of linagliptin on membrane DPP-4 expression in AGE-exposed HUVECs remains unknown. Additional experiments would strengthen the present findings.

Conclusions

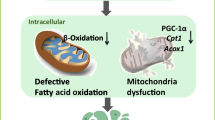

Our present observations suggest AGEs could stimulate the release of DPP-4 from HUVECs via RAGE-mediated ROS generation, which may further augment the AGE-RAGE signaling to EC damage through the interaction with M6P/IGF-IIR (Figure 4).

Abbreviations

- AGEs:

-

Advanced glycation end products

- RAGE:

-

Receptor for AGEs

- DPP-4:

-

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4

- GLP-1:

-

Glucagon-like peptide-1

- GIP:

-

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptides

- ECs:

-

Endothelial cells

- M6P/IGF-IIR:

-

D-Mannose-6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor

- HUVECs:

-

Human umbilical vein ECs

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- ICAM-1:

-

Intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- PAI-1:

-

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- BSA:

-

Bovine serum albumin

- M6P:

-

D-Mannose-6-phosphate

- NAC:

-

N-acetylcysteine

- Ab:

-

Antibody

- IGF-IIR:

-

Insulin-like growth factor II receptor

- M6P/IGF-IIR-Ab:

-

Ab raised against M6P/IGF-IIR

- SPR:

-

Surface plasmon resonance

- KD:

-

Dissociation constant

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- RAGE-Ab:

-

Ab raised against RAGE

- sRAGE:

-

Soluble form of RAGE.

References

Vlassara H, Bucala R: Recent progress in advanced glycation and diabetic vascular disease: role of advanced glycation end product receptors. Diabetes. 1996, 45 (Suppl 3): S65-S66.

Brownlee M, Cerami A, Vlassara H: Advanced glycosylation end products in tissue and the biochemical basis of diabetic complications. N Engl J Med. 1988, 318: 1315-1321. 10.1056/NEJM198805193182007.

Rahbar S: Novel inhibitors of glycation and AGE formation. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2007, 48: 147-157. 10.1007/s12013-007-0021-x.

Yamamoto Y, Kato I, Doi T, Yonekura H, Ohashi S, Takeuchi M, Watanabe T, Yamagishi S, Sakurai S, Takasawa S: Development and prevention of advanced diabetic nephropathy in RAGE-overexpressing mice. J Clin Invest. 2001, 108: 261-268.

Wendt TM, Tanji N, Guo J, Kislinger TR, Qu W, Lu Y, Bucciarelli LG, Rong LL, Moser B, Markowitz GS: RAGE drives the development of glomerulosclerosis and implicates podocyte activation in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Am J Pathol. 2003, 162: 1123-1137. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63909-0.

Yamagishi S, Imaizumi T: Diabetic vascular complications: pathophysiology, biochemical basis and potential therapeutic strategy. Curr Pharm Des. 2005, 11: 2279-2299. 10.2174/1381612054367300.

Yamagishi S, Nakamura K, Matsui T, Noda Y, Imaizumi T: Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE): a novel therapeutic target for diabetic vascular complication. Curr Pharm Des. 2008, 14: 487-495. 10.2174/138161208783597416.

Jandeleit-Dahm K, Cooper ME: The role of AGEs in cardiovascular disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2008, 14: 979-986. 10.2174/138161208784139684.

Tahara N, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Honda A, Tahara A, Nitta Y, Kodama N, Mizoguchi M, Kaida H, Ishibashi M: Positive association between serum level of glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end products and vascular inflammation evaluated by [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Diabetes Care. 2012, 35: 2618-2625. 10.2337/dc12-0087.

Cordero OJ, Salgado FJ, Nogueira M: On the origin of serum CD26 and its altered concentration in cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009, 58: 1723-1747. 10.1007/s00262-009-0728-1.

Yazbeck R, Howarth GS, Abbott CA: Dipeptidyl peptidase inhibitors, an emerging drug class for inflammatory disease?. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009, 30: 600-607. 10.1016/j.tips.2009.08.003.

Kim W, Egan JM: The role of incretins in glucose homeostasis and diabetes treatment. Pharmacol Rev. 2008, 60: 470-512. 10.1124/pr.108.000604.

Yamagishi S, Matsui T: Pleiotropic effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)-based therapies on vascular complications in diabetes. Curr Pharm Des. 2011, 17: 4379-4385. 10.2174/138161211798999456.

Ikushima H, Munakata Y, Ishii T, Iwata S, Terashima M, Tanaka H, Schlossman SF, Morimoto C: Internalization of CD26 by mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor contributes to T cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000, 97: 8439-8444. 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8439.

Yamagishi S, Nakamura K, Matsui T, Inagaki Y, Takenaka K, Jinnouchi Y, Yoshida Y, Matsuura T, Narama I, Motomiya Y: Pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits advanced glycation end product-induced retinal vascular hyperpermeability by blocking reactive oxygen species-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor expression. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281: 20213-20220. 10.1074/jbc.M602110200.

Sasaki N, Takeuchi M, Chowei H, Kikuchi S, Hayashi Y, Nakano N, Ikeda H, Yamagishi S, Kitamoto T, Saito T: Advanced glycation end products (AGE) and their receptor (RAGE) in the brain of patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with prion plaques. Neurosci Lett. 2002, 326: 117-120. 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00310-5.

Tahara N, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Tahara A, Kaifu K, Ueda S, Okuda S, Imaizumi T: Serum levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are independently correlated with circulating levels of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) in humans. Clin Biochem. 2013, 46: 300-303. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.11.023.

Ikushima H, Munakata Y, Iwata S, Ohnuma K, Kobayashi S, Dang NH, Morimoto C: Soluble CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV enhances transendothelial migration via its interaction with mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor. Cell Immunol. 2002, 215: 106-110. 10.1016/S0008-8749(02)00010-2.

Li H, Zhang X, Guan X, Cui X, Wang Y, Chu H, Cheng M: Advanced glycation end products impair the migration, adhesion and secretion potentials of late endothelial progenitor cells. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012, 11: 46-10.1186/1475-2840-11-46.

Ueda S, Yamagishi S, Matsui T, Noda Y, Ueda S, Jinnouchi Y, Sasaki K, Takeuchi M, Imaizumi T: Serum levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are inversely associated with the number and migratory activity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in apparently healthy subjects. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012, 30: 249-254. 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2011.00264.x.

Yan SF, D'Agati V, Schmidt AM, Ramasamy R: Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE): a formidable force in the pathogenesis of the cardiovascular complications of diabetes & aging. Curr Mol Med. 2007, 7: 699-710. 10.2174/156652407783220732.

Lin L, Park S, Lakatta EG: RAGE signaling in inflammation and arterial aging. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2009, 14: 1403-1413.

Lamers D, Famulla S, Wronkowitz N, Hartwig S, Lehr S, Ouwens DM, Eckardt K, Kaufman JM, Ryden M, Müller S, Hanisch FG, Ruige J, Arner P, Sell H, Eckel J: Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a novel adipokine potentially linking obesity to the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2011, 60: 1917-1925. 10.2337/db10-1707.

Ta NN, Li Y, Schuyler CA, Lopes-Virella MF, Huang Y: DPP-4 (CD26) inhibitor alogliptin inhibits TLR4-mediated ERK activation and ERK-dependent MMP-1 expression by U937 histiocytes. Atherosclerosis. 2010, 213: 429-435. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.08.064.

Shah Z, Kampfrath T, Deiuliis JA, Zhong J, Pineda C, Ying Z, Xu X, Lu B, Moffatt-Bruce S, Durairaj R, Sun Q, Mihai G, Maiseyeu A, Rajagopalan S: Long-term dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibition reduces atherosclerosis and inflammation via effects on monocyte recruitment and chemotaxis. Circulation. 2011, 124: 2338-2349. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.041418.

Stange T, Kettmann U, Holzhausen HJ: Immunoelectron microscopic single and double labelling of aminopeptidase N (CD 13) and dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD 26). Acta Histochem. 1996, 98: 323-331. 10.1016/S0065-1281(96)80025-0.

Ishibashi Y, Matsui T, Takeuchi M, Yamagishi S: Sitagliptin augments protective effects of GLP-1 against advanced glycation end product receptor axis in endothelial cells. Horm Metab Res. 2011, 43: 731-734.

Yamagishi S, Adachi H, Nakamura K, Matsui T, Jinnouchi Y, Takenaka K, Takeuchi M, Enomoto M, Furuki K, Hino A: Positive association between serum levels of advanced glycation end products and the soluble form of receptor for advanced glycation end products in nondiabetic subjects. Metabolism. 2006, 55: 1227-1231. 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.05.007.

Nakamura K, Yamagishi S, Adachi H, Matsui T, Kurita-Nakamura Y, Takeuchi M, Inoue H, Imaizumi T: Serum levels of soluble form of receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) are positively associated with circulating AGEs and soluble form of VCAM-1 in patients with type 2 diabetes. Microvasc Res. 2008, 76: 52-56. 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.09.004.

Yamagishi S, Matsui T: Soluble form of a receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) as a biomarker. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2010, 2: 1184-1195.

Raucci A, Cugusi S, Antonelli A, Barabino SM, Monti L, Bierhaus A, Reiss K, Saftig P, Bianchi ME: A soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is produced by proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-bound form by the sheddase a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10). FASEB J. 2008, 22: 3716-3727. 10.1096/fj.08-109033.

Iwaki-Egawa S, Watanabe Y, Kikuya Y, Fujimoto Y: Dipeptidyl peptidase IV from human serum: purification, characterization, and N-terminal amino acid sequence. J Biochem. 1998, 124: 428-433. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022130.

Drucker DJ, Nauck MA: The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2006, 368: 1696-1705. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69705-5.

Baggio LL, Drucker DJ: Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology. 2007, 132: 2131-2157. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.054.

Ide Y, Matsui T, Ishibashi Y, Takeuchi M, Yamagishi S: Pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits advanced glycation end product-elicited mesangial cell damage by blocking NF-kappaB activation. Microvasc Res. 2010, 80: 227-232. 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.03.015.

Ojima A, Ishibashi Y, Matsui T, Maeda S, Nishino Y, Takeuchi M, Fukami K, Yamagishi S: Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist inhibits asymmetric dimethylarginine generation in the kidney of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats by blocking advanced glycation end product-induced protein arginine methyltranferase-1 expression. Am J Pathol. 2013, 182: 132-141. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.09.016.

Yamagishi S, Fujimori H, Yonekura H, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto H: Advanced glycation endproducts inhibit prostacyclin production and induce plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in human microvascular endothelial cells. Diabetologia. 1998, 41: 1435-1441. 10.1007/s001250051089.

Ishibashi Y, Matsui T, Takeuchi M, Yamagishi S: Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) inhibits advanced glycation end product (AGE)-induced up-regulation of VCAM-1 mRNA levels in endothelial cells by suppressing AGE receptor (RAGE) expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010, 391: 1405-1408. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.075.

Ojima A, Matsui T, Maeda S, Takeuchi M, Yamagishi S: Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) inhibits signaling pathways of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in endothelial cells via its antioxidative properties. Horm Metab Res. 2012, 44: 501-505.

Yamagishi S, Amano S, Inagaki Y, Okamoto T, Takeuchi M, Makita Z: Beraprost sodium, a prostaglandin I2 analogue, protects against advanced glycation endproducts-inducede injury in cultured retinal pericytes. Mol Med. 2002, 8: 546-550.

Kusunoki Y, Hayashi T, Morishita Y, Yamaoka M, Maki M, Bean MA, Kyoizumi S, Hakoda M, Kodama K: T-cell responses to mitogens in atomic bomb survivors: a decreased capacity to produce interleukin 2 characterizes the T cells of heavily irradiated individuals. Radiat Res. 2001, 155: 81-88. 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)155[0081:TCRTMI]2.0.CO;2.

Lawson C, Wolf S: ICAM-1 signaling in endothelial cells. Pharmacol Rep. 2009, 61: 22-32.

Tuttolomondo A, Di Raimondo D, Pecoraro R, Arnao V, Pinto A, Licata G: Atherosclerosis as an inflammatory disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2012, 18: 4266-4288. 10.2174/138161212802481237.

Takenaka K, Yamagishi S, Matsui T, Nakamura K, Imaizumi T: Role of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in thrombogenic abnormalities in diabetes. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2006, 3: 73-77. 10.2174/156720206775541804.

Matsui T, Nishino Y, Takeuchi M, Yamagishi S: Vildagliptin blocks vascular injury in thoracic aorta of diabetic rats by suppressing advanced glycation end product-receptor axis. Pharmacol Res. 2011, 63: 383-388. 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.02.003.

Johansen OE, Neubacher D, von Eynatten M, Patel S, Woerle HJ: Cardiovascular safety with linagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pre-specified, prospective, and adjudicated meta-analysis of a phase 3 programme. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012, 11: 3-10.1186/1475-2840-11-3.

Sakata K, Hayakawa M, Yano Y, Tamaki N, Yokota N, Eto T, Watanabe R, Hirayama N, Matsuo T, Kuroki K, Sagara S, Mishima O, Koga M, Nagata N, Nishino Y, Kitamura K, Kario K, Takeuchi M, Yamagishi SI: Efficacy of alogliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, on glucose parameters, the activity of the advanced glycation end product - receptor for advanced glycation end product axis, and albuminuria in Japanese type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2013, 10.1002/dmrr.2437.

Raposeiras-Roubín S, Rodiño-Janeiro BK, Paradela-Dobarro B, Grigorian-Shamagian L, García-Acuña JM, Aguiar-Souto P, Jacquet-Hervet M, Reino-Maceiras MV, Alvarez E, González-Juanatey JR: Predictive value of advanced glycation end products for the development of post-infarction heart failure: a preliminary report. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012, 11: 102-10.1186/1475-2840-11-102.

Sarashina A, Sesoko S, Nakashima M, Hayashi N, Taniguchi A, Horie Y, Graefe-Mody EU, Woerle HJ, Dugi KA: Linagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor in development for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a phase I, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of single and multiple escalating doses in healthy adult male Japanese subjects. Clin Ther. 2010, 32: 1188-1204. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.06.004.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (to S.Y.), and by MEXT-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) (to S.Y.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Dr. Yamagishi has received honoraria such as lecture fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YI, TM, SM, and YH acquired and interpreted data. SY mainly contributed to the present study, conceptualized and designed the study, acquired, analyzed, and interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript, and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ishibashi, Y., Matsui, T., Maeda, S. et al. Advanced glycation end products evoke endothelial cell damage by stimulating soluble dipeptidyl peptidase-4 production and its interaction with mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor. Cardiovasc Diabetol 12, 125 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-12-125

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-12-125