Abstract

Background

Ticks and tick-borne diseases are increasingly recognized as a cause of disease in dogs worldwide. The epidemiology of ticks and tick-transmitted protozoa and bacteria has changed due to the spread of ticks to urban and peri-urban areas and the movement of infected animals, posing new risks for animals and humans. This countrywide study reports information on distribution and prevalence of pathogens in ticks collected from privately-owned dogs in Italy.

We analyzed 2681 Ixodidae ticks, collected from 1454 pet dogs from Italy. Specific PCR protocols were used to detect i) Piroplasms of the genera Babesia and Theileria, ii) Gram-negative cocci of the family Anaplasmataceae and iii) Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Sequencing of positive amplicons allowed for species identification.

Results

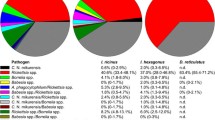

Babesia/Theileria spp. DNA was detected in 435 homogeneous tick-pools (Minimum Infection Rate (MIR) = 27.6%; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 25.4–29.8%) with higher prevalence in Ixodes ricinus and Rhipicephalus sanguneus group. The zoonotic B. venatorum was the most prevalent species (MIR = 7.5%; 95% CI = 6.3–9.0%). Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species were detected in 165 tick-pools (MIR = 10.5%; 95% CI = 9.3–11.8%) and specifically, A. phagocytophilum was identified with MIR = 5.1% (95% CI = 4.1–6.3%). Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. and B. afzelii were detected with MIR = 0.4% (95% CI = 0.2–0.8%) and MIR = 0.3% (95% CI 0.1–0.7%) respectively.

Conclusions

Zoonotic pathogens B. venatorum and A. phagocytophilum were the most frequently detected in ticks collected from privately-owned dogs which might be used as markers of pathogens presence and distribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ixodid ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) are, after mosquitoes, the leading vectors of pathogens of medical and veterinary importance on a global scale [1]. They are ectoparasites of domestic and wild animals, as well as humans, and feed on vertebrate hosts to develop and reproduce. While feeding, they can transmit viruses, bacteria, protozoa and helminths that may subsequently infect the host [2]. Globally, the incidence/prevalence of tick-borne diseases is rising [3, 4], mostly due to increased interactions between pathogens, vectors and hosts. Some of the most important factors that account for the increasing incidence include urbanization and human population growth, behavioral changes such as human encroachment into natural environments, climate and habitat changes, and increased wildlife populations in urban and peri-urban areas [5, 6].

Tick-borne pathogens (TBPs) able to cause disease in humans are overwhelmingly zoonotic [7]. Domestic dogs may be infected with TBPs of sylvatic origin and are also competent reservoirs for human tick-transmitted infectious agents, such as Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia ewingii, and Rickettsia conorii [8]. Wild animals are usually considered the main reservoir hosts of TBPs like Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (s.l.), Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Babesia venatorum and B. microti [9,10,11,12]. Dogs provide a means by which infected ticks can be carried into domestic settings, thus enhancing the risk of human infection, and can act as “sentinels” for monitoring the risk of human disease in an endemic area [13, 14].

Several country-wide studies have been made in Europe to assess ticks and TBPs presence and distribution in companion animals [15,16,17,18,19,20]. In Italy, several efforts have been made to evaluate the prevalence of circulating tick-borne pathogens in ticks collected from dogs [21, 22], although limited to certain areas. In order to better understand the distribution of TBPs in Italy, we propose the first large-scale molecular survey on TBPs harbored in ticks collected from privately-owned dogs [23]. We selected as target TBPs protozoa of the genera Babesia and Theileria, bacteria belonging to the family Anaplasmataceae and to the Borrelia burgdorferi s.L. complex. All target TBPs were chosen for their importance in human and/or animal health.

Results

A total of 2681 Ixodidae ticks grouped into 1578 homogeneous pools were included (Table 1). The analyzed samples originated from 1454 privately-owned dogs from 78 Italian NUTS3 provinces (hereinafter NUTS3, Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics, level 3), (mean = 18.64 dogs/province, standard deviation = 24.75) and 1389 municipalities (LAU2, Local Administrative Units, level 2).

Babesia/Theileria

DNA of protozoa belonging to the genera Babesia and Theileria was detected in 435 pools (MIR = 27.6%; 95% CI = 25.4–29.8) from 395 dogs.

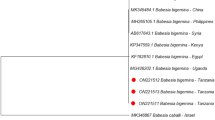

A significantly higher prevalence was found in I. ricinus (χ2 = 5.5, p = 0.02) and in ticks of the R. sanguineus group (χ2 = 4.1, p = 0.04) compared to other tick species as well as in adult ticks (χ2 = 9.99, p = 0.001) and engorged females (χ2 = 15.82, p = 0.000). Coinfection with Piroplasms and Anaplasmataceae was reported in 63 tick pools (n = 47 pools of adult I. ricinus, n = 2 pools of adult I. hexagonous and n = 11 pools of adult and n = 1 nymph pools of R. sanguineus group). Dogs living in urban environments were at a lower risk of carrying a Babesia/Theileria-infected tick (odds ratio (OR) = 0.31; 95% CI = 0.24–0.39) compared to dogs living in rural and forest habitats; housing (indoor, garden, kennel) did not influence the risk of being parasitized by an infected tick (p > 0.05). Breed, sex and age had not significant association with the infection status of ticks (p > 0.05). Geographical distribution at the NUTS3 level of Babesia/Theileria-infected ticks is reported in Fig. 1. Piroplasms were detected in 53 provinces (53/78 = 68, 95% CI = 57.0–77.2%) (Fig. 1a) with significant differences among the provinces (p < 0.05). Considering NUTS3 provinces where at least 20 dogs were sampled, piroplasms were detected with MIR values ranging from 0% (95% CI = 0.0–17.6%) to 61.9% (95% CI = 40.9–79.3%) (Additional file 1: Table S1, Fig. 1b). Regular antiparasitic treatment reduced the risk of being parasitized by Babesia/Theileria-positive ticks (OR = 0.24; 95% CI = 0.19–0.31). Although dogs treated with collars (OR = 6.99; 95% CI = 3.89–12.55) and spot-on products (OR = 7.75; 95% CI = 5.18–11.59) were more likely to be parasitized than those treated with oral formulations. Sequencing determined the presence of at least 9 species of the genus Babesia and 5 species belonging to the genus Theileria, as reported in Table 2. For 37 PCR-positive samples, sequencing was not possible due to low-quality DNA. The zoonotic B. venatorum was the most prevalent species (MIR = 7.5%; 95% CI = 6.3–9.0%), followed by unspecified Babesia spp. (MIR = 4.4%; 95% CI = 3.5–5.5%) and B. capreoli (MIR = 3.6%; 95% CI = 2.7–4.6%). Other zoonotic isolates belonged to the B. microti group, which were reported with MIR = 2.4% (95% CI =1.8–3.3%). For 4 tick-pools, it was possible to specifically determine the presence of B. microti “Munich-type” (MIR = 0.3%; 95% CI = 0.1–0.7%). Piroplasms with the domestic dog as their primary reservoir host were reported with a lower prevalence (B. canis MIR = 0.4, 95% CI = 0.2–0.8%; B. vogeli MIR = 0.6, 95% CI = 0.3–1.2%). The geographical distribution of zoonotic and dog-related piroplasms is reported in Fig. 2.

Geographical distribution, at the NUTS3 level, of ticks infected with Babesia/Theileria piroplasms (a) Anaplasma/Ehrlichia spp. (c) and Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. (e), Minimum Infection Rate (MIR%) in NUTS3 provinces where at least 20 dogs were sampled, for Babesia/Theileria (b), Anaplasma/Ehrlichia (d) and B. burgdorferi s.l. (f). Map created in QGIS 3.4.10 [24]

Zoonotic (B. venatorum and B. microti) and dog-related (B. canis, B. vogeli and B. vulpes n. sp.) Babesia spp. geographical distribution at NUTS3 level. Map created in QGIS 3.4.10 [24]

Anaplasma/Ehrlichia

Genomic DNA of Gram-negative bacteria of the genera Anaplasma and Ehrlichia was detected in 165 tick- pools (MIR = 10.5%; 95% CI = 9.3–11.8%) from 160 dogs.

A higher prevalence was found in I. ricinus (OR = 5.33; 95% CI = 3.70–7.67), while ticks of the genus Rhipicephalus were significantly less infected (OR = 0.19; 95% CI = 0.13–0.27). Engorged I. ricinus females were more infected than other developmental stages (OR = 2.39; 95% CI = 1.48–3.53). A higher infection prevalence was found in tick-pools of dogs from forest environments compared to dogs living in only urban or rural environments (OR = 5.27; 95% CI = 3.66–7.59). Housing, breed, sex, age and the use of antiparasitic treatment had no effect on the risk of being parasitized by infected ticks (p > 0.05). Geographical distribution at NUTS3 level of Anaplasma/Ehrlichia-infected ticks is reported in Fig. 1. Anaplasma/Ehrlichia DNA was detected in 46 of the 78 (59%) provinces sampled (95% CI = 47.89–69.22%) (Fig. 1c) with differences between the NUTS3 provinces (p = 0.01). Considering NUTS3 where at least 20 dogs were sampled, Anaplasma/Ehrlichia DNA was detected with MIR values ranging from 0% (95% CI = 0.0–15.5%) to 22.7% (95% CI = 10.1–43.4%) (Additional file 1: Table S2, Fig. 1d). The zoonotic A. phagocytophilum was identified by sequencing in 80 tick-pools (MIR = 5.1, 95% CI = 4.1–6.3%) from 35 provinces, while A. platys and E. canis, which cause cyclic canine thrombocytopenia and canine monocytic ehrlichiosis, were detected in 13 (MIR = 0.8%; 95% CI = 0.5–1.4%) and 21 (MIR = 1.3%; 95% CI = 0.9–2.0%) pools respectively. A. ovis was detected in 3 tick-pools from Catania province (Sicily, Southern Italy) (MIR = 0.2, 95% CI = 0.1–0.6%). Uncultured Anaplasma spp. was amplified from 36 pools (MIR = 2.3, 95% CI = 1.7–3.1%) and uncultured Ehrlichia spp. from 12 pools (MIR = 0.8, 95% CI = 0.4–1.3%), including 1 isolate from northeastern Italy of Candidatus E. walkerii [GenBank: AY098730], previously identified in I. ricinus ticks attached to asymptomatic human patients from the same part of Italy [25]. Table 2 reports the overall sequencing results for Anaplasma/Ehrlichia related to tick species. Figure 3 shows the geographical distribution of zoonotic and canine-related Anaplasmataceae (A. platys and E. canis).

Zoonotic (A. phagocytophilum) and dog-related (A. platys and E. canis) Anaplasma and Ehrlichia spp. geographical distribution at NUTS3 level. Map created in QGIS 3.4.10 [24]

B. Burgdorferi s.l.

B. burgdorferi s.l. DNA was detected in 10 tick pools (MIR = 0.6, 95% CI = 0.3–1.2%) from 10 different dogs. All infected pools were comprised of adult individuals (n = 8 non-engorged adults and n = 2 engorged females). Infected pools belonged to the genus Ixodes (I. ricinus n = 4, I. hexagonous n = 1) and to the R. sanguineus group, with no statistically significant differences among genera or species due to the small number of positive samples. One fully engorged I. ricinus female was at the same time positive by PCR for Anaplasma/Ehrlichia. All dogs with B. burgdorferi s.l. positive ticks were housed indoors with access to a garden. Seven dogs regularly attended rural and forest environments, while 3 lived exclusively in an urban setting. Antiparasitic treatment was reported for 6 dogs, but active in only 2 dogs. Sequencing identified n = 6 B. burgdorferi s.l. and n = 4 B. afzelii (Table 2). Geographical distribution at NUTS3 level of B. burgdorferi s.l. is reported in Fig. 1 (cf also Additional file 1: Table S3). B. burgdorferi s.l. was detected in 11.5% of the sampled NUTS3 provinces (95% CI = 6.2–20.5%).

Discussion

Ticks and tick-borne diseases have shown patterns of “general emergence” over the past few decades [26]. When pets like domestic dogs are involved, they are perceived by public opinion as a significant threat to both animal and human health [4, 7, 8]. Protozoa of the genera Babesia/Theileria were detected in 27.6% of the examined tick pools, with a higher prevalence in I. ricinus, which is the second most frequently reported tick affecting Italian dogs [23]. The importance of I. ricinus in relation to the epidemiology of Babesia and Theileria is confirmed by the large variety of species infecting this tick species. Piroplasms for which wild animals are the definitive reservoir hosts were detected with a higher prevalence in Ixodes species, especially the zoonotic B. venatorum. Given its widespread distribution, feeding habits and anthropophagic behavior, I. ricinus can transmit a wide variety of pathogens, linking together sylvatic, rural and peri-urban environments [27]. Notably, other zoonotic Babesia species, i.e. B. microti and B. microti “Munich-type”, were detected not only in I. ricinus but also in R. sanguineus group, I. hexagonus and D. marginatus. Isolates of B. vulpes n. sp. [28] were detected with a higher prevalence in I. hexagonus, but also in I. ricinus and R. sanguineus group, as previously reported [29, 30]. Clinical symptoms in dogs infected with B. vulpes n. sp. include pale mucous membranes, anorexia, apathy and fever with severe macrocytic/hypochromic regenerative anemia and thrombocytopenia [28, 31, 32]. Particular attention should be paid to this emergent canine pathogen, which is considered to be endemic in most European countries [33]. The lower percentage of infected tick-pools found on dogs which attend exclusively urban environments reflects the lower burden of canine piroplasms (B. canis and B. vogeli) detected only in the competent vector, R. sanguineus group [34]. B. canis was in fact detected in 0.4% of sequenced tick-pools, B. vogeli from 0.6%. Regular antiparasitic treatments in dogs are important not only for preventing tick-infestation and canine TBPs, but especially in the context of public health. From a geographical point of view, our results confirm the widespread nationwide presence of piroplasms, with 68% of the sampled provinces positive for Babesia or Theileria. A higher prevalence of infection was reported in northern Italy (OR = 7.50, 95% CI 5.24–10.73), compared to central and southern provinces.

DNA of bacteria of the Anaplasmataceae family was reported in 46 of the sampled NUTS3 provinces (59% of the Italian territory included in the study) with an overall prevalence in tick pools of 10.5%. The highest infection prevalence was recorded in ticks from the NUTS3 in northern Italy, except for the province of Messina in Sicily, an area traditionally endemic for Anaplasma [35]. Here, 3 pools of R. sanguineus group were infected with A. ovis. Engorged females of I. ricinus were the most infected class of ticks, followed by I. hexagonus. R. sanguineus group was found to be infected with the highest variety of Anaplasmataceae species. Anaplasma phagocytophilum was the most widespread species detected in tick-pools positive at Anaplasma/Ehrlichia PCR and was detected with the highest MIR in I. hexagonus (MIR = 41.7%), followed by I. ricinus (MIR = 11.4%) and R. sanguineus group (MIR = 1.8%). I. ricinus is the primary vector of A. phagocytophilum in Europe, but the high infection rate of I. hexagonus confirms the important role that hedgehogs and hedgehog ticks may play in the epidemiology of A. phagocytophilum in Europe [36]. Previous studies report A. phagocytophilum in ticks of domestic dogs and wild carnivores from Italy, with a prevalence ranging from 0 to 16.6% [22, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. A. platys and E. canis were reported in tick pools from both northern and southern provinces (p > 0.05), in contrast with previous reports of higher seroprevalence levels in dogs from southern Italy [45, 46] and Sardinia [47]. Notably, E. canis DNA was detected in R. sanguineus group, which is its main tick vector in Mediterranean areas [48], but also with higher MIR in I. ricinus (OR = 15.15, 95% CI 3.47–66.16) and I. hexagonus (OR = 10.07, 95% CI 1.4–72.34).

Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. DNA was detected with low prevalence across the country, in both I. ricinus and R. sanguineus group. The geographical distribution of ticks infected with B. burgdorferi s.l. shows isolated infected tick pools from 8 of the 78 examined NUTS3 provinces, while in the province of Oristano (Sardinia) 2 tick pools from 2 different dogs were infected with B. burgdorferi s.l. A cross-sectional seroepidemiological study carried out in Sardinia [49] reported a seroprevalence of 6.1% in teen-agers but showed no association between seropositivity and pet ownership. In other Italian regions, anti-B. burgdorferi antibodies are present in the human population with a prevalence that varies considerably between geographical areas (from 0 to 23.2%) [50]. The results of our study confirm the localized distribution of B. burgdorferi, while the low number of ticks submitted from the northeastern regions of Italy (traditionally highly endemic for B. burgdorferi s.l.) [50] did not allow a detailed assessment of the epidemiological situation of dog-infesting ticks from this area.

B. burgdorferi s.l. DNA was detected in ticks infesting dogs exposed not only to rural and sylvatic environments, but also in ticks of dogs exposed to urban environments.

Conclusions

The results obtained from this study highlight the high variability of piroplasms, Anaplasmatacea and Spirochaetae in dog-infesting ticks in Italy. Our data confirm that the emergence of TBPs, which have mainly wild reservoir hosts (i.e. roe deer for B. venatorum and wild rodents for B. burgdorferi s.s. and small mammals and wild ungulates for A. phagocytophilum) [9, 51,52,53], are not limited or confined to sylvatic and rural environments but are increasingly reported in anthropic biological communities (human, pet and, as in the present work, the ectoparasites of owned/pet dogs). The overall high prevalence of TBPs in ticks of privately-owned dogs reflects the importance of an in-depth understanding of ticks and TBPs by veterinary practitioners and veterinary authorities, which must duly inform pet owners and assist them in accessing preventive care through ectoparasitic treatments. A comparable extensive survey on TBPs infectious status of privately-owned dogs is greatly needed to complete the risk assessment of human exposure to zoonotic and tick-related infectious agents.

Methods

Sample collection and pathogen identification

A nationwide survey of ticks collected from privately-owned dogs in Italy was carried out over 20 months, from February 2016 to September 2017. The project involved 153 veterinary practices from 64 Italian provinces. Veterinarians were asked to check five randomly chosen dogs per month for ticks, and to complete a questionnaire for each dog. Each dog included in the study was only sampled once. The questionnaire requested information on date of sampling, geographical origin, breed, sex, age, coat length and ectoparasiticidal treatment history, housing and life environment. All collected ticks were morphologically identified at species level [54,55,56], and epidemiological risk factors as well as the owners’ habits regarding antiparasitic drug usage were evaluated, as reported by Maurelli et al. [23].

Results of morphological and molecular identification of the ticks analyzed in the present study has been previously reported [23]. We included in the present work only those tick species that are commonly reported to feed on dogs (Table 1). Identified ticks were divided into pools comprised of specimens collected from the same dog and homogeneous for species, developmental stage, sex and macroscopic engorgement status, then ginned with a sterile scalpel. The resulting material was homogenized in TRI-Reagent® (Sigma-Aldrich, Italy) and total DNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions with additional overnight incubation in Proteinase K (0.8 mg) and 500 μl of TRI-Reagent.

To detect Babesia spp. and Theileria spp., a semi-nested PCR targeting the V4 hypervariable region of the 18S rDNA using primers RLB-F2 (5′-GACACAGGGAGGTAGTGACAAG-3′), RLB-R2 (5′-CTAAGAATTTCACCTCTGACAGT-3′) and RLB-FINT (5′-GACAAGAAATAACAATACRGGGC-3′) was performed as described by [57]. For Anaplasmataceae, the 16S rDNA was targeted using primers PER1 (5′-TTTATCGCTATTAGATGAGCCTATG-3′) and PER2 (5′-CTCTACACTAGGAATTCCGCTAT-3′) [58]. Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. was detected using the primers FlaF (5′-AGAGCAACTTACAGACGAAATTAAT-3′) and FlaR (5′- CAAGTCTATTTTGGAAAGCACCTAA-3′), targeting a conserved region of the fla gene [59]. Positive (total genomic DNA from cultured parasites or confirmed clinical specimens) and negative controls (sterile bidistilled water) were included in each PCR reaction and all necessary measures were taken to minimize the risk of contamination. The PCR results were expressed as a minimum infection rate (MIR) or the minimum percentage of ticks in a pool with detectable DNA for each specific pathogen. This calculation was based on the assumption that a PCR-positive pool contains only one positive tick [60]. PCR-positive amplicons were purified using a commercial kit (Nucleospin Extract II Kit, Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) and sequenced on both strands (Macrogen Europe, Spain) for species identification. The resulting nucleotide sequences were analyzed using MEGA X software [61] and compared to those available in GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank).

Mapping and statistical analysis

Distributions of tick samples were geo-referenced using QGis [24], entering the owner’s hometown or, if missing, the location of the veterinary practice that enrolled the dog.

Chi-square tests, Odds ratio, logistic regressions and confidence intervals at 95% were calculated using R 3.4.4 [62]. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article and supplementary tables.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- LAU2:

-

Local Administrative Units, level 2

- MIR:

-

Minimum Infection Rate

- NUTS3:

-

Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics, level 3

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- TBP:

-

Tick-borne pathogen

References

Githeko A, Lindsay S, Confalonieri U, Patz J. Climate change and vector-borne diseases: a regional analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(9):1136–47 Available from: https://www.who.int/bulletin/archives/78(9)1136.pdf.

Jongejan F, Uilenberg G. The global importance of ticks. Parasitology. 2004;129:S3–14.

Kjemtrup AM, Conrad PA. Human babesiosis: an emerging tick-borne disease. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30(12–13):1323–37.

Nicholson WL, Allen KE, McQuiston JH, Breitschwerdt EB, Little SE. The increasing recognition of rickettsial pathogens in dogs and people. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26(4):205–12. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2010.01.007.

Colwell DD, Dantas-Torres F, Otranto D. Vector-borne parasitic zoonoses: emerging scenarios and new perspectives. Vet Parasitol. 2011;182(1):14–21. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.07.012.

Mackenstedt U, Jenkins D, Romig T. The role of wildlife in the transmission of parasitic zoonoses in peri-urban and urban areas. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl [Internet]. 2015;4(1):71–9. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2015.01.006.

Baneth G. Tick-borne infections of animals and humans: a common ground. Int J Parasitol [Internet]. 2014;44(9):591–6. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.03.011.

Shaw SE, Day MJ, Birtles RJ, Breitschwerdt EB. Tick-borne infectious diseases of dogs. Trends Parasitol. 2001;17(2):74–80.

Gern L, Estrada-Peña A, Frandsen F, Gray JS, Jaenson TGT, Jongejan F, et al. European reservoir hosts of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Zentralblatt fur Bakteriol. 1998;287(3):196–204.

Stuen S. Anaplasma Phagocytophilum - the most widespread tick-borne infection in animals in Europe. Vet Res Commun. 2007;31(Suppl. 1):79–84.

Leiby DA. Transfusion-transmitted Babesia spp.: Bull’s-eye on Babesia microti. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24(1):14–28.

Yabsley MJ, Shock BC. Natural history of zoonotic Babesia: role of wildlife reservoirs. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2013;2(1):18–31. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2012.11.003.

Cardoso L, Oliveira AC, Granada S, Nachum-Biala Y, Gilad M, Lopes AP, et al. Molecular investigation of tick-borne pathogens in dogs from Luanda, Angola. Parasites and Vectors [Internet]. 2016;9(1):1–6. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1536-z.

Olivieri E, Zanzani SA, Latrofa MS, Lia RP, Dantas-Torres F, Otranto D, et al. The southernmost foci of Dermacentor reticulatus in Italy and associated Babesia canis infection in dogs. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1):213 [cited 2017 Mar 30]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27090579.

Abdullah S, Helps C, Tasker S, Newbury H, Wall R. Ticks infesting domestic dogs in the UK: a large-scale surveillance programme. Parasites and Vectors [Internet]. 2016;9(1):1–9. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1673-4.

Claerebout E, Losson B, Cochez C, Casaert S, Dalemans AC, De Cat A, et al. Ticks and associated pathogens collected from dogs and cats in Belgium. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6(1):1 Available from: Parasites & Vectors.

Davies S, Abdullah S, Helps C, Tasker S, Newbury H, Wall R. Prevalence of ticks and tick-borne pathogens: Babesia and Borrelia species in ticks infesting cats of Great Britain. Vet Parasitol [Internet]. 2017;244(May):129–35. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.07.033.

Duplan F, Davies S, Filler S, Abdullah S, Keyte S, Newbury H, et al. Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Bartonella spp., haemoplasma species and Hepatozoon spp. in ticks infesting cats: a large-scale survey. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11(1):1–9.

Estrada-Peña A, Roura X, Sainz A, Miró G, Solano-Gallego L. Species of ticks and carried pathogens in owned dogs in Spain: results of a one-year national survey. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2017;8(4):443–52.

Livanova NN, Fomenko NV, Akimov IA, Ivanov MJ, Tikunova NV, Armstrong R, et al. Dog survey in Russian veterinary hospitals: tick identification and molecular detection of tick-borne pathogens. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11(1):1–10.

Torina A, Alongi A, Scimeca S, Vicente J, Caracappa S, de la Fuente J. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in ticks in Sicily. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2010;57(1–2):46–8.

Geurden T, Becskei C, Six RH, Maeder S, Latrofa MS, Otranto D, et al. Detection of tick-borne pathogens in ticks from dogs and cats in different European countries. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018;9(6):1431–6. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.06.013.

Maurelli MP, Pepe P, Colombo L, Armstrong R, Battisti E, Morgoglione ME, et al. A national survey of Ixodidae ticks on privately owned dogs in Italy. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11(1):1–10.

QGIS Developmental Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. 2018;3(4):10 https://www.qgis.org/it/site/index.html.

Brouqui P, Sanogo Y, Caruso G, Merola F, Raoult D. Candidatus Ehrlichia walkerii: a new Ehrlichia detected in Ixodes ricinus tick collected from asymptomatic humans in northern Italy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;990:134–40.

Randolph SE. Evidence that climate change has caused “emergence” of tick-borne diseases in Europe? Int J Med Microbiol. 2004;293(37):5–15.

Estrada-Peña A, Jongejan F. Ticks feeding on humans: a review of records on human-biting Ixodoidea with special reference to pathogen transmission. Exp Appl Acarol. 1999;23(9):685–715.

Baneth G, Cardoso L, Brilhante-Simões P, Schnittger L. Establishment of Babesia vulpes n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Babesiidae), a piroplasmid species pathogenic for domestic dogs. Parasites Vectors. 2019;12(1):1–8. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3385-z.

Solano-Gallego L, Sainz Á, Roura X, Estrada-Peña A, Miró G. A review of canine babesiosis: the European perspective. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1):336 [cited 2017 mar 30]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27289223.

Lledó L, Gimenez-Pardo C, Domínguez-Peñafiel G, Sousa R, Gegúndez I, Casado N, et al. Molecular detection of hemoprotozoa and Rickettsia species in arthropods collected from wild animals in the Burgos province, Spain. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10(8):735–8.

Guitián FJ, Camacho AT, Telford SR. Case-control study of canine infection by a newly recognised Babesia microti-like piroplasm. Prev Vet Med. 2003;61(2):137–45.

Miró G, Checa R, Paparini A, Ortega N, González-Fraga JL, Gofton A, et al. Theileria annae (syn. Babesia microti-like) infection in dogs in NW Spain detected using direct and indirect diagnostic techniques: Clinical report of 75 cases. Parasites Vectors. 2015;8(1):1–11 Available from: ???

Nayyar Ghauri H, Ijaz M, Farooqi SH, Ali A, Ghaffar A, Saleem S, et al. A comprehensive review on past, present and future aspects of canine theileriosis. Microb Pathog. 2019;126:116–22. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2018.10.033.

Dantas-Torres F. The brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Latreille, 1806) (Acari: Ixodidae): from taxonomy to control. Vet Parasitol. 2008;152(3–4):173–85.

Torina A, Alongi A, Naranjo V, Scimeca S, Nicosia S, Di Marco V, et al. Characterization of Anaplasma infections in Sicily, Italy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1149:90–3.

Silaghi C, Skuballa J, Thiel C, Pfister K, Petney T, Pfäffle M, et al. The European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus) - a suitable reservoir for variants of Anaplasma phagocytophilum? Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3(1):49–54. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2011.11.005.

Ebani VV, Verin R, Fratini F, Poli A, Cerri D. Molecular survey of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Ehrlichia canis in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Central Italy. J Wildl Dis. 2011;47(3):699–703.

Ebani V, Cerri D, Fratini F, Ampola M, Andreani E. Seroprevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in domestic and wild animals from Central Italy. New Microbiol. 2008;31:371–5.

Aureli S, Galuppi R, Ostanello F, Foley JE, Bonoli C, Rejmanek D, et al. Abundance of questing ticks and molecular evidence for pathogens in ticks in three parks of Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2015;22(3):459–66.

Vascellari M, Ravagnan S, Carminato A, Cazzin S, Carli E, Da Rold G, et al. Exposure to vector-borne pathogens in candidate blood donor and free-roaming dogs of Northeast Italy. Parasites and Vectors [Internet]. 2016;9(1):1–10. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1639-6.

Morganti G, Gavaudan S, Canonico C, Ravagnan S, Olivieri E, Diaferia M, et al. Molecular Survey on Rickettsia spp., Anaplasma phagocytophilum , Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, and Babesia spp. in Ixodes ricinus Ticks Infesting Dogs in Central Italy. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017;17(11):2154 Available from: http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/vbz.2017.2154.

Baráková I, Derdáková M, Selyemová D, Chvostáč M, Špitalská E, Rosso F, et al. Tick-borne pathogens and their reservoir hosts in northern Italy. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018;9(2):164–70.

Da Rold G, Ravagnan S, Soppelsa F, Porcellato E, Soppelsa M, Obber F, et al. Ticks are more suitable than red foxes for monitoring zoonotic tick-borne pathogens in northeastern Italy. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11(1):1–10.

Ebani VV. Serological survey of Ehrlichia canis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in dogs from central Italy: An update (2013–2017). Pathogens. 2019;8(1):3.

Solano-Gallego L, Trotta M, Razia L, Furlanello T, Caldin M. Molecular survey of Ehrlichia canis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum from blood of dogs in Italy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1078:515–8.

Ramos RAN, Latrofa MS, Giannelli A, Lacasella V, Campbell BE, Dantas-Torres F, et al. Detection of Anaplasma platys in dogs and Rhipicephalus sanguineus group ticks by a quantitative real-time PCR. Vet Parasitol. 2014;205(1–2):285–8. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.06.023.

Cocco R, Sanna G, Cillara MG, Tola S, Ximenes L, Pinnaparpaglia ML, et al. Ehrlichiosis and rickettsiosis in a canine population of northern Sardinia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;990:126–30.

Stich R, Schaefer J, Bremer W, Needham G, Jittapalapong S. Host surveys, ixodid tick biology and transmission scenarios as related to the tick-borne pathogen, Ehrlichia canis. Vet Parasitol. 2008;158(4):256–73.

Castiglia P, Mura I, Masia M, Maida I, Solinas G, Muresu E. Prevalence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in Sardinian teenagers. Ann Ig. 2004;16(1–2):103–8.

Santino I, Sessa R, Del Piano M. Lyme borreliosis infection in Europe. Eur J Infl. 2006;4(2):69–75.

Malandrin L, Jouglin M, Sun Y, Brisseau N, Chauvin A. Redescription of Babesia capreoli (Enigk and Friedhoff, 1962) from roe deer (Capreolus capreolus): isolation, cultivation, host specificity, molecular characterisation and differentiation from Babesia divergens. Int J Parasitol. 2010;40(3):277–84. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.08.008.

Keesing F, Hersh MH, Tibbetts M, McHenry DJ, Duerr S, Brunner J, Killilea M, et al. Reservoir competence of vertebrate hosts for Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Emerg Inf Dis. 2012;18(12):2013–6.

Dugat T, Zanella G, Véran L, Lesage C, Girault G, Durand B, et al. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis potentially reveals the existence of two groups of Anaplasma phagocytophilum circulating in cattle in France with different wild reservoirs. Parasites Vectors. 2016;9:596. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1888-4.

Walker A. Ticks of domestic animals in Africa. Edinburgh: Bioscience Reports; 2003. p. 3–210.

Estrada-Pena A, Bouattour A, Camicas JL, Walker AR. Ticks of domestic animals in the Mediterranean region. A guide to the identification of species. 1st ed. Zaragoza: University of Zaragoza; 2004.

Dantas-Torres F, Latrofa MS, Annoscia G, Giannelli A, Parisi A, Otranto D. Morphological and genetic diversity of Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato from the new and old worlds. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:213.

Zanet S, Bassano M, Trisciuoglio A, Taricco I, Ferroglio E. Horses infected by Piroplasms different from Babesia caballi and Theileria equi: species identification and risk factors analysis in Italy. Vet Parasitol. 2017;236:38–41. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.01.003.

Goodman JL, Nelson C, Vitale B, Madigan JE, Dumler JS, Kurtti TJ, et al. Direct cultivation of the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(4):209–15 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8531996.

Skotarczak B, Wodecka B, Cichocka A. Coexistence DNA of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and Babesia microti in Ixodes ricinus ticks from North-Western Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2002;9(1):25–8.

Kramer V, Randolph M, Hui L, Irwin W, Gutierrez A, Duc J. Detection of the agents of human Ehrlichioses in Ixodid ticks from California. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:62–5.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–9.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. https://www.R- project.org/.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely acknowledge all veterinarians who enrolled the dogs and collected tick specimens for their invaluable support and without whom this work could not have been carried out.

Funding

MSD Animal Health contributed to consumables costs (material needed for tick sampling and biomolecular analysis) and Dr. Liliana Colombo (Sr. Spclst. Scientific Marketing Affairs, MSD) handled the logistics of enrolling and registering veterinary practices. The MSD Animal Health sales team helped to recruit participating veterinary practices. Veterinarians did not receive any payment for their participation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SZ drafted the manuscript and performed statistical analysis, EB coordinated laboratory work at Torino University, PP, LC1 and AT performed laboratory analysis, LC2 coordinated dog recruitment at veterinary premises, LR, GC and EZ conceived the study, revised data analysis and finalized the manuscript, MPM coordinated data analysis and laboratory work at Naples University. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Department Council of Dept. of Veterinary Sciences, University of Turin – Italy and the University of Naples, Federico II Ethics Committee approved the current research. Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all dogs’ owners.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

For each NUT3 (Province) where a minimum of 20 dogs was sampled, Babesia/Theileria Minimum Infection Rate (MIR) was calculated with Confidence Interval (CI) at 95%, Chi Square (χ2), Chi Square p-value (*significant values at p < 0.05) and Odds Ratio (with CI at 95%). Table S2. For each NUT3 (Province) where a minimum of 20 dogs had been sampled, Anaplasma/Ehrlichia Minimum Infection Rate (MIR) was calculated with Confidence Interval (CI) at 95%, Chi Square (χ2; calculated where applicable), Chi Square p-value (*significant values at p < 0.05) or Fisher Exact test p value (**significant values at p < 0.05) and Odds Ratio (with CI at 95%). Table S3. For each NUT3 (Province) where Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. was detected by PCR, we calculated Minimum Infection Rate (MIR) with Confidence Interval (CI) at 95%, Fisher Exact test p value (*significant values at p < 0.05) and Odds Ratio (with CI at 95%).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zanet, S., Battisti, E., Pepe, P. et al. Tick-borne pathogens in Ixodidae ticks collected from privately-owned dogs in Italy: a country-wide molecular survey. BMC Vet Res 16, 46 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-2263-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-2263-4