Abstract

Background

It is now widely accepted that the mixed effect and success rates of strategies to improve quality and safety in health care are in part due to the different contexts in which the interventions are planned and implemented. The objectives of this study were to (i) describe the reporting of contextual factors in the literature on the effectiveness of quality improvement strategies, (ii) assess the relationship between effectiveness and contextual factors, and (iii) analyse the importance of contextual factors.

Methods

We conducted an umbrella review of systematic reviews searching the following databases: PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Embase and CINAHL. The search focused on quality improvement strategies included in the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group taxonomy. We extracted data on quality improvement effectiveness and context factors. The latter were categorized according to the Model for Understanding Success in Quality tool.

Results

We included 56 systematic reviews in this study of which only 35 described contextual factors related with the effectiveness of quality improvement interventions. The most frequently reported contextual factors were: quality improvement team (n = 12), quality improvement support and capacity (n = 11), organization (n = 9), micro-system (n = 8), and external environment (n = 4). Overall, context factors were poorly reported. Where they were reported, they seem to explain differences in quality improvement effectiveness; however, publication bias may contribute to the observed differences.

Conclusions

Contextual factors may influence the effectiveness of quality improvement interventions, in particular at the level of the clinical micro-system. Future research on the implementation and effectiveness of quality improvement interventions should emphasize formative evaluation to elicit information on context factors and report on them in a more systematic way in order to better appreciate their relative importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A growing body of research demonstrates the effectiveness of strategies to improve quality and enhance patient safety (QI strategies) [1]. Yet, at the same time the contextual factors affecting the implementation and effectiveness of these strategies are not well understood [2]. Grimshaw et al. provided the first comprehensive review on the effect of interventions to change provider behaviour [3]. This overview of systematic reviews provided invaluable insight into the effectiveness of quality improvement strategies. It raised concerns about the strength of the evidence base and noted that the majority of interventions are effective under some circumstances, although the authors did not systematically explore what such circumstances might be. Scott conducted a similar, albeit less detailed review and concluded that few studies so far have investigated contextual and implementation factors in detail [4]. More recently, Conry et al. conducted yet another review of interventions to improve the quality of care in hospitals and concluded that the lack of theoretically sound research methods that elucidated why interventions work (or do not work) might be a key reason for the slow uptake of the research evidence in health care settings [5].

It is now accepted that the mixed effect and success rates of QI strategies are in part due to the different contexts in which the interventions are planned and implemented [6–8]. An intervention that works in one setting does not necessarily work in another. ‘Context’ for quality improvement has been defined to include those factors that potentially mediate the effect of the intervention, such as leadership, personal skills, organizational resources or data availability [8]. More recently, specific definitions and categorizations of context have been proposed [9, 10]. Often it is neither feasible nor appropriate to adjust for these factors in an analysis of effectiveness. This is, firstly, because it is unlikely that data on all such factors are available and, secondly, because adjustment for context might mask rather than highlight the importance of such factors. As the potential generalisability of findings on the effectiveness of QI strategies (which often include organizational interventions) is much more limited than the generalizability of clinical trials (for example on the pharmacokinetic response to a drug in a defined group of patients), the question ‘does the QI strategy work’ is only of initial interest. The broader question ‘why, when, where, and for whom it works most effectively’ is of much greater concern and practical importance [11]. Having a thorough understanding of the underlying mechanisms that make an intervention work, will allow for successful application of the intervention in other settings and help improving its effectiveness.

The objectives of this paper are therefore to (i) describe the reporting of contextual factors in the literature on the effectiveness of QI strategies, (ii) assess the relationship between these contextual factors and the effectiveness of QI strategies, and (iii) analyze the importance of contextual factors.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a review of systematic reviews of the literature on the effectiveness of QI strategies [12]. The following electronic databases were searched: PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Embase and CINAHL. The search was limited to literature reviews published in English language between January 2000 and November 2012. The search focused on QI strategies included in the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group taxonomy, which include various forms of continuing medical education (CME), quality assurance projects, financial, organizational, or regulatory interventions that can affect the ability of health care professionals to deliver services more effectively and efficiently [13]. A Boolean search strategy for PubMed was developed (see Additional file 1) covering all quality management topics, including a combination of text words and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, searched in titles and abstracts of studies. The Boolean search strategy was adapted for the other databases.

Methods of screening and selection criteria

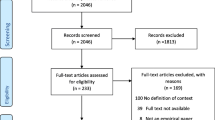

The review strategy was guided by a manual for performing systematic literature reviews on a health services research topic [14]. The results from the databases were checked for duplicates using Reference Manager. This was followed by a three-step screening procedure. Studies were excluded if they did not focus on the effectiveness, performance or impact of quality management strategies in hospital settings. An initial screening of studies was based on titles and abstract, performed by two reviewers (OG, DK) independently. In the second screening, the full texts of the reviews were assessed for inclusion by OG and DK independently. In the third step, the final list of included studies was evaluated for their completeness by a panel of quality management experts from European countries, comprised of mostly senior researchers and medical professionals who participated in a European Commission (EC) funded research project (Deeping our understanding of quality improvement in Europe (DUQuE), see www.duque.eu and acknowledgment section). This evaluation led to five additions to the publication list. Only systematic literature reviews with a focus on the effectiveness, performance or impact of quality management strategies in hospital settings were included. This covered both qualitative and qualitative reviews and meta-analyses. Figure 1 shows the complete study selection process, including the number of disagreements among reviewers which were resolved by a third independent reviewer (RS).

Study selection process. Legend: Figure 1 indicates the study selection process of the systematic literature review

Data extraction

Data on the effectiveness of quality management strategies and the influence of both internal and external contextual factors were extracted using a structured data entry form. Panel experts from the DUQuE team were each independently assigned to extract the data from a limited set of studies which fit with their expertise. The following information was extracted from the studies that met our inclusion criteria: type of QI intervention, number of included studies and participants, objective, description of intervention, description of primary and secondary outcome, effect of primary and secondary outcome, and contextual factors.

Data extraction on contextual factors was categorized according to an assessment tool based on the Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ) (Textbox 1) [9]. We coded context-based factors against the MUSIQ tool and added up the number of studies which displayed each one and noted if the study had produced an effective outcome.

The MUSIQ tool was developed by Kaplan et al. to facilitate research on the contextual factors affecting QI strategies, and has been shown to be reliable and valid [9, 15]. It identifies 25 contextual factors for quality improvement, covering six overarching themes that they labelled as: external environment, organization, quality improvement capacity, the clinical microsystem, the quality improvement team, and a number of miscellaneous issues. Detailed descriptions of the six themes and 25 contextual factors are included in Additional file 2: Table S1.

Textbox 1: Domains of the MUSIQ Tool [9]

● | External environment (external motivators, project sponsorship), |

● | Organization (QI leadership, senior leader project sponsor, culture supportive of QI, maturity of organizational QI, physician payment structure), |

● | Quality improvement support and capacity (data infrastructure, resource availability, workforce focus on QI), |

● | Microsystem (QI leadership, culture supportive of QI, capability for improvement, motivation to change), |

● | Quality improvement team (team diversity, physician involvement, subject matter expert, team tenure, prior experience with QI, team leadership, team decision-making process, team norms and team QI skill) and |

● | Miscellaneous (trigger events, task strategic importance to the organization). |

All data entry forms were double-checked by two independent reviewers (OG, DK) and complemented or altered when both reviewers agreed. In case of disagreement, a third independent reviewer (RS) made the final decision. The quality of the included studies was assessed using a valid and reliable [16, 17] measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews (AMSTAR) [18]. The overall quality of each study was assessed by the proportion of items of the AMSTAR Checklist each study complied with (number of “Yes” answers to 11 questions). Studies are rated as low quality when AMSTAR score is 0–4, moderate quality when AMSTAR score is 5–8, and high quality when AMSTAR score 9–11 [19]. The quality assessment was undertaken by two independent reviewers (OG, DK).

Ethics

This research did not involve human subjects. Ethics approval is covered by the DUQUE project, financed by the EU Commission under grant agreement number 241822 and approved by the Health department of the Government of Catalonia, Spain.

Results

We included 56 systematic reviews in this study (Fig. 1).

The reviews address QI interventions such as health care accreditation (n = 3), local leadership (n = 1), continuing medical education (n = 3), nurturing patient safety cultures (n = 2), promoting organizational culture (n = 3), computerised clinical decision support systems (n = 16), guideline dissemination and implementation (n = 2), interventions to improve patient handovers (n = 5), patient-centred care interventions (n = 3), six sigma and lean continuous quality improvement interventions (n = 3), the use of performance information (n = 6), audit and feedback (n = 2), hospital incident reporting (n = 2), safety checklists (n = 1), educational outreach visits (n = 1), and multi-faceted quality improvement interventions (n = 3). Table 1 gives an overview of all studies included, by type of QI intervention, author, year, AMSTAR score, number of studies included (Table 1). In addition, it specifies the countries included and the number of participants. Reviews included between 2 and 235 individual studies, covering mostly North America, Europe and South-East Asia, with very few studies from South America and the African continent. The median AMSTAR score is 7 (moderate quality), but for studies published from 2010 onwards it increased to 8.5 (moderately high quality) (see also Table 1, footnote for comparison of average AMSTAR code by year).

In Additional file 3: Table S2 we summarize the information on contextual factors extracted from the systematic reviews. For each study, we identified the type of contextual factor according to the MUSIQ model and describe how they relate to QI effectiveness (Additional file 3: Table S2). Only 35 of the 56 studies described contextual factors related with the effectiveness of QI interventions. Other studies were exclusively focussed on describing the effectiveness of QI interventions, keeping the contextual factors outside the scope of their study. The most frequently reported contextual factors that were found to be associated with the effectiveness of interventions were the following: external environment (external motivator, n = 4), organization (maturity of organizational QI, n = 5; QI leadership, n = 4), QI support and capacity (resource availability, n = 6; data infrastructure, n = 5), micro-system (capability for improvement, n = 5; culture supportive of QI, n = 3), and QI team (physician involvement, n = 5; team diversity, n = 4; including a subject matter expert, n = 3). Contextual factors identified in the MUSIQ tool but not reported in the reviews were QI team norms, task strategic importance to the organization and trigger events. Contextual factors that are not currently included in the MUSIQ tool, but were reported in various studies (n = 8) included organizational level of programme implementation, patient turnover and bed occupancy, staffing levels, quality of evidence and guidelines, maturity of systems on which CDSS are based, trust in and quality of information sources and educational outreach visitors [20–27]. In the following section we summarize these contextual factors using the six domains of the MUSIQ model: external environment, organization, quality improvement capacity, the clinical micro-system, the quality improvement team, and miscellaneous issues.

External environment

In terms of direct effects, financial incentives or administrative support were related with the effectiveness of QI strategies [5, 28]. Resource requirements, too, were a key factor, in particular for large up-front organizational support and capital investment required to introduce a Computerised Physician Order Entry [29]. QI strategies were not equally effective across health care settings: Clinical decision support systems (CDSS) were more effective in institutional settings than community settings due to types of conditions, stricter controls on professional behaviour, and different attitudes of professionals towards externally imposed rules [30]. The external environment also affected the interpretation of QI effectiveness more broadly. Priority areas of external inspections differed between high and low income countries, making the results of studies on the effectiveness of accreditation programmes difficult to compare and transfer [31].

Organization

There was a substantial amount of literature referring to the effect of supportive organizational cultures [21, 32, 33]. The creation of a patient safety culture (including having clear policies and actively support training) positively impacted on the effectiveness of infection control policies [21], on the implementation of Six Sigma and Lean approaches to QI) [32]. The visible support of managerial staff (both at ward/unit and above ward/unit level) also impacted positively on the effectiveness of accreditation of health care services [34], on clinical decision support systems [35], and on hospital incident reporting [26].

Another example for organizational context factors was the embedding of feedback systems in organizational QI: Feedback on a physician’s clinical performance was more likely to be effective when provided by an authoritative, credible source, systematically over multiple years [36], and a high frequency of performing audit and feedback increased its effectiveness in modifying health professionals’ behaviour [37]. Having a closed safety-feedback cycle (e.g. effective dissemination channels and the capacity for rapid action) at all levels of the organization positively affected the effectiveness of hospital incident reporting [26].

The absence of an effective multidisciplinary infection control team perceived as exercising positive leadership at ward or unit level was a risk for the effectiveness of infection control strategies on health care associated infections [21].

QI support and capacity

The availability and functionality of information technology (IT) systems facilitated data collection and improved the effectiveness of QI interventions [38], notably, interventions targeting handovers [24], accreditation programs in rural health care services [34], and Six Sigma [39]. Sufficient resources, too, were paramount for the implementation of QI strategies [38, 40, 41]. Insufficient administrative support impacted on the effectiveness of interventions promoting safety cultures [41] or on strategies aimed at implementing quality indicators [40]. An excessive workload (not matched to available staffing) and insufficient staff training were a risk for the effectiveness of Six Sigma [39] and infection control strategies on health care associated infections [21]. High staff turnover and an excessive use of external staff members limited the effectiveness of infection control strategies [21].

Microsystem

Clinical micro-systems have previously been described as the key settings in which QI interventions are implemented [42–46]. Low staff morale and scepticism of health care professionals towards the positive impact of QI interventions (e.g. accreditation programs or CDSS) on the quality of health care services were serious barriers to the successful implementation of QI interventions [21, 23, 33]. Alignment of physicians’ views on the content and implementation of interventions aimed at improving handovers was beneficial to its effectiveness [24, 47]. The training or education in the proper use of QI strategies (e.g. safety checklists, accreditation standards) was beneficial to the effectiveness of the QI strategies [34, 48]. Integrating QI strategies in the working practices of health professionals promoted the effectiveness of the QI strategies [23] and the ‘motivation to change’ [22, 40].

QI team

Team composition is a major determinant for QI effectiveness. Involving physicians in the development and implementation of QI interventions (such as CDSS, accreditation programs, audit and feedback) has been shown to be an important success factor for their effectiveness [22, 23, 34, 37, 49]. Involving multidisciplinary QI teams (including nurses and physicians, and sometimes also pharmacists) in the development and implementation of QI strategies increased the effectiveness of the intervention [22, 24, 50, 51]. ‘Subject matter experts’, where more than one team member has detailed knowledge about the outcome, process, or system being changed were shown to be beneficial for the a range of QI strategies (CDSS, CME, Six Sigma and Lean). Awareness, attitude, knowledge of and understanding performance data (generic ‘QI skills’) [52] were all essential facilitators for the implementation of QI interventions.

Miscellaneous

A number of additional contextual factors were identified from the literature, not all of which are addressed in the MUSIQ tool. These include, in particular, structural factors of service organization, including turnover of staff or bed occupancy [21], workload and time constraints [24], but also the flexibility to update the QI intervention (guidelines or computerised decision support systems) [22, 23]. Detailed information on the contextual factors identified in the literature is presented in Additional file 3.

Discussion

A number of previous studies have reviewed the effectiveness of quality improvement strategies, but this is to our best knowledge the first study to systematically assess a broad range of associated context factors and their relationship with the effectiveness of multiple quality improvement strategies in health care. This study has shown that, overall, context factors were poorly reported in the current literature. This is a very important finding since those studies that did report it demonstrated substantial differences in QI effectiveness, depending on the presence or absence of contextual factors. Given the heterogeneity of the literature few systematic reviews included in the analysis were able to pursue a quantitative synthesis and stratify this analysis on the context factors identified.

Context factors most frequently reported related to the three MUSIQ domains microsystem, QI support and capacity or QI team. This aligns with recent analysis of the concepts underlying the MUSIQ tool, which identified that these domains exhibit significant effects on QI performance outcomes [15]. Of significance for improvement efforts these domains are also most amenable to local adjustment. We also identified context factors that are not currently included in the MUSIQ tool, such as those relating to structural characteristics or the heterogeneity observed in the relationship between context and multiple outcome measures [20–27]. Since the publication of the MUSIQ tool several other key publications on the role of context have emerged [2, 10, 15, 53]. Our findings might help to inform these conceptual developments. Moreover, our data may lead to reflections on the broad conceptual nature of existing context models (which emphasize multi-level structures, the role of the external environment, the organization at large and clinical practice), while it seems that all three key domains emerging from this review broadly relate to the clinical microsystem.

Implications of the study

This study has important implications for future research on the relationship between QI context and effectiveness. For some QI interventions the evidence is substantial, and is supported by clear recommendation on how context factors mediate effectiveness (e.g. the Cochrane review on audit and feedback [37] gives clear indication on the factors and the magnitude to which they increase or attenuate the effect of QI strategies). For other QI interventions, the evidence base is still weak and adaptation and implementation should be pursued with caution, since generalisability is limited when context factors are unknown.

Future studies on the effectiveness of QI interventions need to place more emphasis on studying and reporting outcomes in relation to contextual factors [53]. Pooled averages are misleading and do not reflect the varying contexts in which QI are implemented. Ideally, alongside major evaluations of effectiveness, studies should be conducted looking at context factors and recording such factors using existing tools (e.g. [9, 53]). This would permit future reviews on the effectiveness of QI to stratify on the type of context, sample size permitting. In parallel, qualitative studies (including ethnographic studies) could be conducted to gain a deeper understanding of professional, organizational, cultural and structural context factors [54]. This would be a complex and difficult undertaking. For example, a true investigation of context factors cannot be achieved retrospectively at the stage of writing up a research project, but rather requires engaging multiple perspectives and stakeholders from the start to ensure all relevant aspects of QI implementation (both formal and informal) are considered. Once identified, such factors need to be observed and monitored over time and statistical models could aim to assess the association of context factors with the effectiveness of QI interventions, where appropriate. We have recently illustrated some of the methodological challenges related to these tasks [55, 56] and at current, the multiple relationships and pathways between exposure, outcome, and context variables in research on QI strategies are not yet sufficiently understood. Alternatively, context might be considered as an integral component of the subject area that evolves, changes and interacts with the intervention during the time period of QI project implementation. In this case, in-depth qualitative assessment is needed. Finally, the research output should report on the role of context factors in order to facilitate generalisability and replicability of the QI intervention. This issue, too, has been subject to debate and the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines are one approach to address a better understanding of QI context factors [57]. The SQUIRE guidelines demonstrate the difficulties and practical issues when reporting on the factors that potentially impact on a QI intervention. Nevertheless, improving understanding, conceptualization, analysis and reporting of context factors in QI is important to advance the field of research. It will help in understanding the mixed results of some QI interventions and help replicate successful projects or, equally important, inform implementers were replication is unlikely to be successful due to different contexts. Our findings suggest that some of the most relevant context factors are those close to the clinical microsystem in which the QI intervention is delivered. This provides cues for action for improvement practitioners who may include an assessment of such factors, and dedicated change processes, in their local plans for quality improvement.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. The main limitation is that the field of research addressing the role of contextual factors in QI is still developing and currently there is no clear consensus on how to define or assess context factors, which has implications for the reviews included in our umbrella review. While we were able to apply the MUSIQ tool to categorize context factors and facilitate data extraction from the literature, the lack of clear search terms may mean that we might have missed reviews for our study. Moreover, it is unclear how contextual factors were assessed in the original studies included in our list of systematic reviews. This may potentially induce publication bias as positive associations are more likely to have been reported. A meta-regression analysis of the effect of context factors, adjusting for publication bias, would be desirable, but given the heterogeneous reporting of the findings in the literature this was not possible at present. We intentionally searched only for the literature that primarily addressed the effectiveness of QI strategies (and not for literature that primarily addressed context factors), as our key interest was the effect of QI and how it is affected by context. In comparison, much of the context literature does not report specifically on QI effectiveness and includes also largely qualitative and mixed methods research. An assessment of this literature would have been beyond the scope of this paper. While acknowledging these limitations, the findings of this review are nevertheless important for an advancement of the understanding of how context factors shape the effectiveness of quality improvement interventions.

Conclusions

Contextual factors may influence the effectiveness of quality improvement interventions, in particular at the level of the clinical microsystem. Future research on the implementation and effectiveness of QI interventions should emphasize formative evaluation to elicit information on context factors and report on them in a more systematic way in order to better appreciate their relative importance.

Abbreviations

- AMSTAR:

-

A measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews

- CDSS:

-

Clinical decision support systems

- CME:

-

Continuing medical education

- DUQuE:

-

Deeping our understanding of quality improvement in Europe

- EC:

-

European commission

- EPOC:

-

Group taxonomy: Cochrane effective practice and organisation of care group taxonomy

- MeSH:

-

Medical subject headings

- MUSIQ:

-

Model for understanding success in quality

- QI:

-

Quality improvement

- QI strategies:

-

Strategies to improve quality and enhance patient safety

- SQUIRE guidelines:

-

Standards for quality improvement reporting excellence guidelines

References

Shojania KG, McDonald KM, Wachter RM. Closing the quality gap: A critical analysis of quality improvement strategies. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004.

Bate P, Robert G, Fulop N, Ovretveit J, Dixon-Woods M. Perspectives on context. A selection of essays considerng the role of context in successfull quality improvement. London: The Health Foundation; 2014.

Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001;39 Suppl 2:Ii2–45.

Scott I. What are the most effective strategies for improving quality and safety of health care? Intern Med J. 2009;39:389–400.

Conry MC, Humphries N, Morgan K, McGowan Y, Montgomery A, Vedhara K, et al. A 10 year (2000–2010) systematic review of interventions to improve quality of care in hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:275.

Kaplan HC, Brady PW, Dritz MC, Hooper DK, Linam WM, Froehle CM, et al. The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: a systematic review of the literature. Milbank Q. 2010;88:500–59.

Dixon-Woods M, Bosk CL, Aveling EL, Goeschel CA, Pronovost PJ. Explaining Michigan: developing an ex post theory of a quality improvement program. Milbank Q. 2011;89:167–205.

Ovretveit J. Understanding the conditions for improvement: research to discover which context influences affect improvement success. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20 Suppl 1:i18–23.

Kaplan HC, Provost LP, Froehle CM, Margolis PA. The Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:13–20.

Tomoaia-Cotisel A, Scammon DL, Waitzman NJ, Cronholm PF, Halladay JR, Driscoll DL, et al. Context matters: the experience of 14 research teams in systematically reporting contextual factors important for practice change. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11 Suppl 1:S115–23.

Foy R, Ovretveit J, Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Taylor SL, Dy S, et al. The role of theory in research to develop and evaluate the implementation of patient safety practices. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:453–9.

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Methodology for Joanna Briggs Institute Umbrella Reviews. Secondary Methodology for Joanna Briggs Institute Umbrella Reviews [http://www.joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/jbc/introductions/scientificCommittee/oct13/ATTACH6a_JBIUmbrella-Review-methodology.pdf]

EPOCGroup. EPOC Taxonomy Secondary EPOC Taxonomy 2013 [http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-resources].

van de Voorde C, Leonard C. Search for evidence and critical appraisal: health services research. KCE Process notes. Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE); 2007.

Kaplan HC, Froehle CM, Cassedy A, Provost LP, Margolis PA. An exploratory analysis of the model for understanding success in quality. Health Care Man Rev. 2013;38:325–38.

Kang D, Wu Y, Hu D, Hong Q, Wang J, Zhang X. Reliability and external validity of AMSTAR in assessing quality of TCM systematic reviews. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine. eCAM. 2012;2012:732195.

Su N, Lu J, Li C, Chen L, Shi Z. [Assessment of reliability and validity of assessment of multiple systematic reviews in chinese systematic reviews on stomatology]. Hua xi kou qiang yi xue za zhi. Huaxi kouqiang yixue zazhi. 2013;31:49–52.

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10.

Seo HJ, Kim KU. Quality assessment of systematic reviews or meta-analyses of nursing interventions conducted by Korean reviewers. BMC Med Res Meth. 2012;12:129.

Morello RT, Lowthian JA, Barker AL, McGinnes R, Dunt D, Brand C. Strategies for improving patient safety culture in hospitals: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:11–8.

Griffiths P, Renz A, Hughes J, Rafferty AM. Impact of organisation and management factors on infection control in hospitals: a scoping review. J Hosp Infect. 2009;73:1–14.

Chan AJ, Chan J, Cafazzo JA, Rossos PG, Tripp T, Shojania K, et al. Order sets in health care: a systematic review of their effects. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28:235–40.

Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Devereaux PJ, Beyene J, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293:1223–38.

Ong MS, Coiera E. A systematic review of failures in handoff communication during intrahospital transfers. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37:274–84.

Schauffler HH, Mordavsky JK. Consumer reports in health care: do they make a difference? Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:69–89.

Benn J, Koutantji M, Wallace L, Spurgeon P, Rejman M, Healey A, et al. Feedback from incident reporting: information and action to improve patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:11–21.

Thomson O'Brien MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB, Davis DA, Freemantle N, Harvey EL. Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:Cd000125.

Bloom BS. Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:380–5.

Kaushal R, Shojania KG, Bates DW. Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication safety: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1409–16.

Pearson SA, Moxey A, Robertson J, Hains I, Williamson M, Reeve J, et al. Do computerised clinical decision support systems for prescribing change practice? A systematic review of the literature (1990–2007). BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:154.

Flodgren G, Pomey MP, Taber SA, Eccles MP. Effectiveness of external inspection of compliance with standards in improving healthcare organisation behaviour, healthcare professional behaviour or patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:Cd008992.

Glasgow JM, Scott-Caziewell JR, Kaboli PJ. Guiding inpatient quality improvement: a systematic review of Lean and Six Sigma. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36:533–40.

Alkhenizan A, Shaw C. Impact of accreditation on the quality of healthcare services: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31:407–16.

Greenfield D, Braithwaite J. Health sector accreditation research: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20:172–83.

Main C, Moxham T, Wyatt JC, Kay J, Anderson R, Stein K. Computerised decision support systems in order communication for diagnostic, screening or monitoring test ordering: systematic reviews of the effects and cost-effectiveness of systems. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1–227.

Veloski J, Boex JR, Grasberger MJ, Evans A, Wolfson DB. Systematic review of the literature on assessment, feedback and physicians’ clinical performance: BEME Guide No. 7. Med Teach. 2006;28:117–28.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:Cd000259.

Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:iii–iv. 1–72.

Nicolay CR, Purkayastha S, Greenhalgh A, Benn J, Chaturvedi S, Phillips N, et al. Systematic review of the application of quality improvement methodologies from the manufacturing industry to surgical healthcare. Br J Surg. 2012;99:324–35.

de Vos M, Graafmans W, Kooistra M, Meijboom B, Van Der Voort P, Westert G. Using quality indicators to improve hospital care: a review of the literature. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21:119–29.

Weaver SJ, Lubomksi LH, Wilson RF, Pfoh ER, Martinez KA, Dy SM. Promoting a culture of safety as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:369–74.

Mitchell IA, McKay H, Van Leuvan C, et al. A prospective controlled trial of the effect of a multi-faceted intervention on early recognition and intervention in deteriorating hospital patients. Resuscitation. 2010;81:658–66.

Godfrey MM, Melin CN, Muething SE, Batalden PB, Nelson EC. Clinical microsystems, Part 3. Transformation of two hospitals using microsystem, mesosystem, and macrosystem strategies. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:591–603.

Blegen MA, Sehgal NL, Alldredge BK, Gearhart S, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Improving safety culture on adult medical units through multidisciplinary teamwork and communication interventions: the TOPS Project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:346–50.

Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. NEJM. 2006;355:2725–32.

Pronovost PJ, Goeschel CA, Colantuoni E, et al. Sustaining reductions in catheter related bloodstream infections in Michigan intensive care units: observational study. BMJ. 2010;340:c309.

Shepperd S, Parkes J, McClaren J, Phillips C. Discharge planning from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;1:Cd000313.

Ko HC, Turner TJ, Finnigan MA. Systematic review of safety checklists for use by medical care teams in acute hospital settings—limited evidence of effectiveness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:211.

Damiani G, Pinnarelli L, Colosimo SC, Almiento R, Sicuro L, Galasso R, et al. The effectiveness of computerized clinical guidelines in the process of care: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:2.

Aboelela SW, Stone PW, Larson EL. Effectiveness of bundled behavioural interventions to control healthcare-associated infections: a systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Infect. 2007;66:101–8.

Stone PW, Pogorzelska M, Kunches L, Hirschhorn LR. Hospital staffing and health care-associated infections: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:937–44.

Ketelaar NA, Faber MJ, Flottorp S, Rygh LH, Deane KH, Eccles MP. Public release of performance data in changing the behaviour of healthcare consumers, professionals or organisations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:Cd004538.

Stange KC, Glasgow RE. Contextual Factors: The Importance of Considering and Reporting on Context in Research on the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013.

Leslie M, Paradis E, Gropper MA, Reeves S, Kitto S. Applying ethnography to the study of context in healthcare quality and safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:99–105.

Groene O. Does quality improvement face a legitimacy crisis? Poor quality studies, small effects. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2011;16:131–2.

Groene O, Sunol R. The investigators reflect: what we have learned from the Deepening our Understanding of Quality Improvement in Europe (DUQuE) study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26 Suppl 1:2–4.

Ogrinc G, Mooney SE, Estrada C, Foster T, Goldmann D, Hall LW, et al. The SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17 Suppl 1:i13–32.

Lam-Antoniades M, Ratnapalan S, Tait G. Electronic continuing education in the health professions: an update on evidence from RCTs. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29:44–51.

Thomson O'Brien MA, Freemantle N, Oxman AD, Wolf F, Davis DA, Herrin J. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;2:Cd003030.

Parmelli E, Flodgren G, Beyer F, Baillie N, Schaafsma ME, Eccles MP. The effectiveness of strategies to change organisational culture to improve healthcare performance: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6:33.

Scott T, Mannion R, Marshall M, Davies H. Does organisational culture influence health care performance? A review of the evidence. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8:105–17.

Brand CA, Barker AL, Morello RT, Vitale MR, Evans SM, Scott IA, et al. A review of hospital characteristics associated with improved performance. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24:483–94.

Bright TJ, Wong A, Dhurjati R, Bristow E, Bastian L, Coeytaux RR, et al. Effect of clinical decision-support systems: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:29–43.

Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, Maglione M, Mojica W, Roth E, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:742–52.

Damiani G, Pinnarelli L, Scopelliti L, Sommella L, Ricciardi W. A review on the impact of systematic safety processes for the control of error in medicine. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15:Ra157–66.

Hemens BJ, Holbrook A, Tonkin M, Mackay JA, Weise-Kelly L, Navarro T, et al. Computerized clinical decision support systems for drug prescribing and management: a decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6:89.

Jamal A, McKenzie K, Clark M. The impact of health information technology on the quality of medical and health care: a systematic review. HIM J. 2009;38:26–37.

Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330:765.

Sahota N, Lloyd R, Ramakrishna A, Mackay JA, Prorok JC, Weise-Kelly L, et al. Computerized clinical decision support systems for acute care management: a decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review of effects on process of care and patient outcomes. Implement Sci. 2011;6:91.

Shojania KG, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:Cd001096.

Wong K, Yu SK, Holbrook A. A systematic review of medication safety outcomes related to drug interaction software. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2010;17:e243–55.

Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Thomas R, MacLennan G, Ramsay C, Fraser C, et al. Toward evidence-based quality improvement. Evidence (and its limitations) of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies 1966–1998. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21 Suppl 2:S14–20.

Arora VM, Manjarrez E, Dressler DD, Basaviah P, Halasyamani L, Kripalani S. Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:433–40.

Gordon M, Findley R. Educational interventions to improve handover in health care: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2011;45:1081–9.

Mistiaen P, Francke AL, Poot E. Interventions aimed at reducing problems in adult patients discharged from hospital to home: a systematic meta-review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:47.

Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ. 2007;335:24–7.

Lewin SA, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, Zwarenstein M, Dick J. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:Cd003267.

DelliFraine JL, Langabeer 2nd JR, Nembhard IM. Assessing the evidence of Six Sigma and Lean in the health care industry. Qual Manag Health Care. 2010;19:211–25.

Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH. The public release of performance data: what do we expect to gain? A review of the evidence. JAMA. 2000;283:1866–74.

Hysong SJ. Meta-analysis: audit and feedback features impact effectiveness on care quality. Med Care. 2009;47:356–63.

Percarpio KB, Watts BV, Weeks WB. The effectiveness of root cause analysis: what does the literature tell us? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:391–8.

O'Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:Cd000409.

Acknowledgements

The DUQuE Project Consortium comprises: Klazinga N, Kringos DS, MJMH Lombarts and Plochg T (Academic Medical Centre—AMC, University of Amsterdam, THE NETHERLANDS); Lopez MA, Secanell M, Sunol R and Vallejo P (Avedis Donabedian University Institute-Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona FAD. Red de investigación en servicios de salud en enfermedades crónicas REDISSEC, SPAIN); Bartels P (Central Denmark Region & The Department of Clinical Medicine, Aalborg University, Denmark), Kristensen S (Central Denmark Region & Center for Healthcare Improvements, Aalborg University, DENMARK); Michel P and Saillour-Glenisson F (Comité de la Coordination de l’Evaluation Clinique et de la Qualité en Aquitaine, FRANCE); Vlcek F (Czech Accreditation Committee, CZECH REPUBLIC); Car M, Jones S and Klaus E (Dr Foster Intelligence-DFI, UK); Bottaro S and Garel P (European Hospital and Healthcare Federation-HOPE, BELGIUM); Saluvan M (Hacettepe University, TURKEY); Bruneau C and Depaigne-Loth A (Haute Autorité de la Santé-HAS, FRANCE); Shaw C (University of New SouthWales, AUSTRALIA); Hammer A, Ommen O and Pfaff H (Institute for Medical Sociology, Health Services Research and Rehabilitation Science, University of Cologne-IMVR, GERMANY); Groene O (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK); Botje D andWagner C (The Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research—NIVEL, The NETHERLANDS); Kutaj-Wasikowska H and Kutryba B (Polish Society for Quality Promotion in Health Care-TPJ, POLAND); Escoval A and Lívio A (Portuguese Association for Hospital Development-APDH, PORTUGAL) and Eiras M, Franca M and Leite I (Portuguese Society for Quality in Health Care-SPQS, PORTUGAL); Almeman F, Kus H and Ozturk K (Turkish Society for Quality Improvement in Healthcare-SKID, TURKEY); Mannion R (University of Birmingham, UK); Arah OA, DerSarkissian M, Thompson CA andWang A (University of California, Los Angeles—UCLA, USA); Thompson A (University of Edinburgh, UK).

The study, “Deepening our Understanding of Quality Improvement in Europe (DUQuE)” has received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n° 241822.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design: OG. Acquisition of data: DK, OG. Interpretation of data: DK, RS, CW, PM, RM, NK, OG. Drafting of the manuscript: OG, DK. Critical revision: DK, RS, CW, PM, RM, NK, OG. Overall approval of the paper: DK, RS, CW, PM, RM, NK, OG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Dionne S. Kringos and Oliver Groene contributed equally to this work.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Search strategy. The Boolean search strategy which was developed for PubMed. It covers all quality management topics, including a combination of text words and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, searched in titles and abstracts of studies. The Boolean search strategy was adapted for the other databases.

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Contextual factors included in the Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ). Detailed descriptions of the six themes and 25 contextual factors that are included in the Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ).

Additional file 3: Table S2.

Context factors and their impact on the effectiveness of quality improvement strategies. Summary of the information on contextual factors extracted from the systematic reviews. For each study, we identified the type of contextual factor according to the MUSIQ model and describe how they relate to QI effectiveness.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kringos, D.S., Sunol, R., Wagner, C. et al. The influence of context on the effectiveness of hospital quality improvement strategies: a review of systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res 15, 277 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0906-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0906-0