Abstract

Background

Family members do not have an official position in the practice of euthanasia and physician assisted suicide (EAS) in the Netherlands according to statutory regulations and related guidelines. However, recent empirical findings on the influence of family members on EAS decision-making raise practical and ethical questions. Therefore, the aim of this review is to explore how family members are involved in the Dutch practice of EAS according to empirical research, and to map out themes that could serve as a starting point for further empirical and ethical inquiry.

Methods

A systematic mixed studies review was performed. The databases Pubmed, Embase, PsycInfo, and Emcare were searched to identify empirical studies describing any aspect of the involvement of family members before, during and after EAS in the Netherlands from 1980 till 2018. Thematic analysis was chosen as method to synthesize the quantitative and qualitative studies.

Results

Sixty-six studies were identified. Only 14 studies had family members themselves as study participants. Four themes emerged from the thematic analysis. 1) Family-related reasons (not) to request EAS. 2) Roles and responsibilities of family members during EAS decision-making and performance. 3) Families’ experiences and grief after EAS. 4) Family and ‘the good euthanasia death’ according to Dutch physicians.

Conclusion

Family members seem to be active participants in EAS decision-making, which goes hand in hand with ambivalent feelings and experiences. Considerations about family members and the social context appear to be very important for patients and physicians when they request or grant a request for EAS. Although further empirical research is needed to assess the depth and generalizability of the results, this review provides a new perspective on EAS decision-making and challenges the Dutch ethical-legal framework of EAS. Euthanasia decision-making is typically framed in the patient-physician dyad, while a patient-physician-family triad seems more appropriate to describe what happens in clinical practice. This perspective raises questions about the interpretation of autonomy, the origins of suffering underlying requests for EAS, and the responsibilities of physicians during EAS decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Euthanasia and physician assisted suicide (EAS) seems to be an accepted practice in the Netherlands, although the legislation and practical implications of EAS are still subject to intense debate [1, 2]. Both in 1992 and in 2017, public acceptance of EAS was found to be around 90% [3]. In the Netherlands, euthanasia is defined as the active termination of a patient’s life at their explicit request, by a physician who administers a lethal substance to the patient [4]. In physician assisted suicide, a physician supplies the lethal substance to a patient who ingests the substance in the presence of the physician.

Dutch physicians are not persecuted for performing EAS if they comply with the due care criteria as formulated in the euthanasia law. First, the physician must be convinced that the patient’s request for EAS is well-considered and voluntary, and that the patient’s suffering is lasting and unbearable. In addition, the patient has to be informed about his situation and prognosis, there must be no other reasonable solution and a second, independent physician has to be consulted. Last, the termination of a life or an assisted suicide has to be performed with due care [4]. After EAS has been performed, the physician must notify a municipal pathologist and reports written by the physician and the independent consultant are sent to a regional euthanasia review committee that evaluates whether the due care criteria have been met.

While the Dutch euthanasia law was enacted in 2002, the performance of and empirical research on EAS already started in the 1980s [5, 6]. Regularly performed empirical studies show that EAS is still relatively rare. In 2015, euthanasia accounted for 4.5% of annual deaths, physician assisted suicide for only 0.1% [7]. According to the latest annual report of the Dutch euthanasia review committees, EAS was carried out most often by general practitioners (GPs), namely in 85% of cases. In 80% of all cases EAS took place at home and in 65% of the cases it involved patients with incurable cancer [8].

The family’s role in the Dutch practice of euthanasia and assisted suicide has been receiving critical attention lately, although their involvement had already been documented before and shortly after the enactment of the euthanasia law [9, 10]. Recent qualitative studies describe how family members such as partners and children can influence the process of euthanasia decision-making and how some physicians take family members’ well-being and bereavement into account when deciding whether or not to grant a request [11, 12]. In contrast to these findings, the Dutch euthanasia law does not consider the position of family members at all, except that requests for EAS need to be free of undue pressure. Dutch clinical guidelines on EAS also barely describe the position and relevance of family members in EAS decision-making [13]. Hence, empirical findings on the involvement of family members in the practice of EAS raise practical and ethical questions, which require further examination from both an empirical and ethical perspective [11, 14, 15].

To date, a systematic review of empirical research addressing the involvement of family members in the Dutch practice of EAS has not been performed. Several authors have described different aspects of family involvement, such as the different roles family members may take in euthanasia decision-making [10], the bereavement process of relatives after EAS [14, 16] and the potential influence of family members’ suffering on end-of-life decision-making [15]. However, there is no comprehensive overview that incorporates all elements that might be relevant for the Dutch practice of EAS. Meanwhile, there is a growing body of literature in the fields of medical ethics and palliative care that underlines the relevance of the patient’s significant others in medical decision-making and its consequences for clinical practice, and several authors have called for further empirical inquiry [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25].

Therefore, the aim of this review is to explore how family members are involved in the Dutch practice of EAS, according to empirical research, and to map out themes that could serve as a starting point for further empirical research and ethical discussion. A systematic review was performed with a broad research question: what do both qualitative and quantitative studies on EAS from the Netherlands reveal regarding the involvement of family members before, during and after EAS? The question who the ‘family members’ are is part of this research question. In the context of Dutch healthcare, the term ‘family’ is mostly used for (marital) partners and first-degree blood relatives (parents, children and siblings). However, a patient’s social network may be constituted differently, and people other than marital partners or blood relatives may be closer to the patient and may be far more important in the process of medical decision-making [26]. Therefore, this specific point needs close examination as well. Notwithstanding the focus on the Dutch situation, the results of this study could offer new insights into the practice of physician assisted dying generally, and could inform both the national and international debate on its legislation and practical implications.

Methods

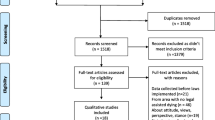

A systematic search strategy for mixed studies reviews was used, following the PRISMA guidelines [27, 28]. First, a primary search was carried out in the databases Pubmed, Embase, PsycInfo, and Emcare with the use of the search strategy as displayed in Table 1. Second, some additional articles were retrieved by snowballing and checking references. Additionally, experts in the field were asked about key documents on the topic. Two researchers screened titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles to determine their eligibility for the review. This was followed by a full-text screening of the remaining articles by three researchers. The inclusion criteria were original, empirical, scholarly research considering any aspect of the involvement of family members in the Dutch euthanasia practice from 1980 until 2017, published in English or Dutch. Disagreements on the inclusion or exclusion of articles were discussed among the three researchers. If necessary, authors were contacted for additional information.

Early in the process of reviewing the empirical studies, it became clear that there was much variety in terms of objectives, methods and quality, and that there were differences in the underlying epistemological positions. In addition, the involvement of family members was not the primary objective of study in a considerable number of studies, though they were referred to in the results. To come to a meaningful synthesis in light of this heterogeneity, an inductive qualitative approach was chosen for the synthesis of the included studies [29]. To synthesize the results of both qualitative and quantitative studies, thematic analysis was adopted as method, which is a useful approach when describing and mapping out an underexplored area [30, 31]. Following this approach, studies were not excluded based on their quality. The first researcher performed line-by-line coding of the results sections of the included studies and attributed descriptive themes. The descriptive themes were discussed among the three researchers to reach consensus on their accuracy and meaning. Subsequently, analytical themes that overarch the descriptive themes were developed during group discussions and were tested for their soundness in the included studies. To enhance the researchers’ reflexivity, note-taking, group discussions on personal judgments and an active search for disconfirming cases were carried out during the review process.

Results

The systematic search and selection process yielded 66 studies that met the inclusion criteria. The selection process is presented in the flow diagram in Fig. 1 and the main characteristics of the included studies are displayed in Table 2. Only 14 of the 66 included studies had family members as study participants. Some studies described family members as study participants, although their own opinions or experiences did not seem to be a topic of research, and the results made no further mention of them [32, 33]. These studies were excluded from further analysis. We also excluded a number of studies presenting results on demedicalized assistance in dying (DAS). For the ethnographic studies, the original text was included instead of articles derived from the original studies. Finally, the official governmental evaluations of the euthanasia law were included even though one might consider them grey literature, because they are an important source of empirical data.

In the thematic analysis of the included studies, 19 descriptive themes were identified and four overarching analytical themes were developed. The descriptive and analytical themes are displayed in Table 3 and described in detail in the section below. It was found that the concepts family, family members, relatives, social network, friends and others were used interchangeably across the different studies, often without further clarification of the concepts. An attempt to define the patient’s significant others involved in EAS is found under theme 2.1. Recent and detailed quantitative data necessary for a solid definition turned out to be missing, however.

Theme 1: family-related reasons (not) to make a request for euthanasia or assisted suicide

Considerations about family members and the broader social network were frequently found to play a role in why people made a request for EAS, postponed or withdrew it.

Fear of suffering as witnessed previously in other family members

In all three ethnographic studies and several other qualitative studies, patients are described whose request for euthanasia or assisted suicide is motivated by a fear of the suffering, dependency, uncertainties or strain on caregivers they had witnessed previously surrounding the deathbed of partners, parents or siblings [9, 34,35,36,37,38]. For instance, patients with cancer and AIDS expressed the wish to prevent the suffering they had witnessed at the deathbed of parents or partners by choosing EAS [9, 35]. Family members of patients with cancer recounted similar stories when asked about the patient’s reasons to request euthanasia [34, 38]. In-depth interviews with patients with dementia showed how instructions regarding euthanasia were made in advance following experiences with family members, most often parents, or others they had cared for who were afflicted with dementia [39].

In an interview study, patients with Huntington disease spoke “frequently and spontaneously” about experiences with ill parents or other blood relatives in relation to their wish to have control over the end of their life [37]. In a parallel questionnaire-based study, any thoughts about end-of-life wishes, including EAS, were significantly related to family experiences with the disease, and not to clinical or demographic variables [40]. Similarly, members of the general public referred to situations of decay, pain and humiliation they had seen in family and friends who were afflicted with metastasized cancer or dementia, to explain their positive opinions regarding euthanasia and advance euthanasia directives [41, 42]. Furthermore, ‘experience with EAS in the environment’ was one of the factors significantly related to having an advance euthanasia directive, next to other factors such as being a women, being non-religious, a high education level, the death of a marital partner, inadequate personal care support and several illness-related factors [43].

Family beliefs and dynamics

In several studies, patients and their partner, children or siblings describe how the wish for EAS was part of a personal philosophy of life, developed together long before becoming ill [9, 38, 44]. In one family, both parents and children were members of the right-to-die association [9]. Some patients spoke explicitly about the goal to have a well-organized farewell and aftermath for the sake of their family members [9, 38]. In other instances, family members and physicians related the request for EAS to someone’s position in the family and his/her character [9, 38, 45]. A single case was mentioned of an EAS request relating to a grave family secret [38].

Importance of maintaining meaningful bonds

In qualitative studies on physicians’ and nurses’ experiences with EAS, the healthcare professionals describe how patients’ growing inability to connect meaningfully to significant others can motivate the request for EAS. They describe patients who wanted EAS as soon as they were no longer able to recognize children or partners, or could no longer enjoy their company due to illness-related symptoms [9, 42, 44, 46]. In contrast, there were cases where patients enjoyed positive experiences with for example grandchildren, in conjunction with postponing or being ambivalent regarding their own request for EAS [9, 34, 37]. For some patients, concerns about family members not being able to bear EAS or not being ready for it were reasons to postpone a request for EAS or not to disclose it to their family members [9, 36, 38]. Euthanasia-requests relating to loss of a partner [42] and loneliness [34] were described as well.

Feeling of being a burden

In several qualitative studies, nurses and physicians recount stories of euthanasia-requests related to dependency on the care of children or partners and the associated burden on them [9, 35, 47]. Financial burdens were only mentioned twice in relation to EAS in all included studies, by a patient without insurance who was worried about the financial consequences for his wife [38] and a young AIDS patient who said to prefer euthanasia above suicide because of his life-insurance [9].

Several themes combined

Norwood’s ethnography, conducted in a primary care setting, offers an illustrative example of the themes mentioned above [35]. She describes an 82-year-old cancer patient who requested euthanasia because of unbearable suffering, meaninglessness, and the wish not to be a burden to her daughter. She cancelled it out of consideration for her daughter who was not ready for it yet, regretted the cancellation, but later on enjoyed the company of her granddaughter again. In her comprehensive in-depth interview study on unbearable suffering in patients with an explicit request for euthanasia, Dees et al. describe how medical, psycho-emotional, socio-environmental and existential elements, as well as the person’s biography and character, together constitute the suffering that led to a request for EAS [45]. While the socio-environmental elements found in Dees’s study largely resemble the above-mentioned family-related reasons, psycho-emotional and existential elements such as hopelessness seemed to contribute more to unbearable suffering. In a prospective survey involving end-stage cancer patients in primary care, fear of future suffering and the feeling of being a burden, together with loss of autonomy and physical suffering, were reported more frequently in patients who suffered unbearably [48]. However, neither this study [49] nor a prospective survey among ALS patients [50] found a significant difference in the prevalence of those symptoms between patients with and without an explicit request for EAS.

Quantitative research among physicians: other reasons more important

Whereas qualitative studies turned up a variety of family-related reasons for EAS, this theme was less prominent and emerged differently in quantitative studies in which physicians were asked about their patient’s main reasons to explicitly request EAS. Both in studies with GPs [51,52,53,54] and with (consulting) psychiatrists [7, 55] who had been involved in the care for patients with an explicit request for EAS, ‘feeling of being a burden’ was mentioned as a reason, yet it was among the less important and less frequently cited reasons. Hopelessness and unbearable suffering [51,52,53,54,55], loss of dignity [51, 52, 56], pain [56, 57], tiredness/weakness [51, 52, 57], and dependency [56, 57] were mentioned by physicians as the most important reasons. This pertained both to patients with an underlying physical disorder and with a mental disorder. In one study involving psychiatrists who had cared for psychiatric patients with an explicit request for EAS, the most important reasons cited were depression, major problems in various aspects of life and loss of control [7]. A study on the content of physicians’ reports about patients who received EAS (underlying illness not specified) showed how, in the majority of cases, the suffering was explained in terms of physical symptoms, followed by loss of function, dependency and deterioration [58]. ‘Being a burden’ and loneliness were again mentioned, but relatively rarely. In the study by Jansen et al., GPs mentioned ‘not wanting to be a burden’ more frequently as a reason for an explicit request in patients whose request had been refused [51]. Additionally, in a study on requests for EAS in the absence of a severe disease, physicians described the most important reasons in terms of being weary of life and physical decline, while the patients’ actual problems were mostly characterized as of social origin [59]. Finally, in a recent content analysis of summaries of psychiatric EAS cases provided by the review committees, loneliness and social isolation were mentioned as an important element in 56% of cases, in addition to the psychiatric morbidity [60].

Theme 2: roles and responsibilities of family members during EAS decision-making and performance

Social network involved in decision-making and performance

Both qualitative and quantitative studies show that once a patient has made a request for EAS to a physician, a process of deliberation, decision-making and finally performance starts in which family members seem to be thoroughly involved [7, 9, 11, 34,35,36, 38, 42, 44, 61,62,63,64]. Partners, children and siblings were most frequently mentioned as the patient’s significant others who were involved in the process of decision-making [9, 34,35,36, 38, 44, 61, 64, 65]. Some studies describe how friends [35, 38], neighbors [11], or nurses [34, 35, 38] created a supportive social network during EAS decision-making and performance in cases where family was absent. In two qualitative studies, patients with psychiatric diseases are mentioned who explicitly refused any contact with family members about their request for EAS [7, 64]. Georges’s survey interviews found that most patients had discussed their end-of-life whishes with their family members, mostly partners and children, before explicitly requesting EAS [66]. Muller’s questionnaire-based study from 1996 shows how, in approximately 90% of cases of EAS, GPs and nursing home physicians (NHPs) spoke with the social network, mostly partners and children, about the request, the intention to grant it and how it would be performed [61]. NHPs spoke slightly more often with ‘other family’ and ‘others’, though both categories were not specified any further. Recent quantitative studies have found slightly lower percentages of physicians who discuss the decision to perform EAS with family members [7, 62], while Dutch physicians are still found to speak most frequently about end-of-life decisions with family members, compared to their counterparts in other European countries [67]. In qualitative studies, the actual performance of EAS is described as happening in the presence of partners, parents, siblings and sometimes friends at the bedside [9, 34,35,36, 38, 44, 64, 68]. According to Muller’s study from 1996, partners and children were most often present at the bedside in the homecare setting, while for one-third of patients receiving EAS in nursing homes, no-one from the social network was present [61]. Verhoef et al. described in 1997 how 96% of EAS-deaths took place at home, of which 99% in the presence of others [54]. Another study described a single case of a patient who did not want anyone to be present at the bedside during the administration of EAS [42].

Sounding board for patient and physician

Ethnographies and other interview studies with patients and family members describe how patients asked their family members to consent to EAS [37, 38], how euthanasia-declarations were drawn, signed and discussed collectively [9, 34, 35, 37, 38, 65], and how alternatives and procedures for EAS were discussed among patient, family and physician [9, 34,35,36, 44, 64]. In qualitative interviews with and observations of physicians, it is described how physicians test their impression regarding the voluntariness of the request and the unbearableness of the symptoms in repeated discussions with family members [35, 38]. Likewise, Hanssen’s quantitative study showed that GPs had conversations with the patient in 95% of cases and with family members in 71% of cases to come to a judgment about unbearable suffering [63].

Caregiving, representing, advocating

Case studies and Norwood’s ethnography describe how husbands, wives, siblings, parents and children and also a neighbor acted as informal caregivers during EAS decision-making in general practice, with or without help of professional caregivers [35, 36, 44, 65, 68]. Only Dees et al. lists caregiving responsibilities among the characteristics of family members who participated in their study on EAS decision-making [64]. The care they provided ranged from zero (a nephew) to twenty-four hours a day (husbands and wives).

In addition, family members acted as patients’ advocates as well as family representatives in conversations with physicians, as other ethnographic studies and the in-depth interviews of Ciesielski-Carlucci et al. found. For instance, partners, children or siblings are described who informed the physician about a worsening of symptoms [9, 34, 38], signaled the right moment for the performance of euthanasia [38, 44] or initiated the discussion about EAS on behalf of competent patients who suffered from a progression of the underlying physical disorder [9]. The describes the case of a sister who initiated the conversation about a euthanasia request with the physician, on behalf of her brother whose cognitive abilities were fluctuating due to brain metastases [34]. In an earlier stage of illness, the patient and his sister had already talked extensively about the possible scenarios of illness progression and the request for euthanasia, and the sister had been appointed as his representative. In a study of EAS cases that the regional review committees disapproved of, single cases were described of family members who helped the physician administer lethal medication or who organized an appointment for a family member afflicted with dementia at the specialized End-of-Life clinic [69].

Negotiating the date of performance

Case studies and ethnographies describe how EAS was planned together with family members, taking into account time for leave-taking, family members traveling from abroad, family holidays, birthdays or responsibilities at work [9, 36, 68]. This is echoed in interviews with family members and physicians, who explained that as long as the physical suffering was not too acute or severe, these kinds of family-related considerations were taken very seriously [47]. In contrast, Dees et al. describe how most family members in their study preferred to stay out of the planning of EAS, and that the patient and physician choose a date, depending on many other factors like fears about symptom progression, loss of competency and psychological suffering [64].

Proxy-decision making: children, patients with dementia

Proxy-decision making came explicitly to the fore in studies about euthanasia for patients with dementia and euthanasia for children. A retrospective interview study with nursing home physicians (NHPs) from 2005 described how, in the majority of cases, NHPs discussed advance euthanasia directives by patients with dementia with the patient’s family members or representatives [70]. According to the NHPs in this study, family members wanted to discuss the advance euthanasia directives most often with the purpose of discussing end-of-life policies in general. From a mixed-method study and a qualitative interview study about advance euthanasia directives drawn up by patients with dementia, it emerged that family members were sometimes involved in writing, discussing or interpreting the advance directives [39, 71]. However, the drafting of an advance euthanasia directive was most often initiated by patients themselves [71]. Some patients expected their families to act upon the euthanasia advanced directive at the right moment, even if that moment was not clearly specified [39]. Two studies found that advance euthanasia directives were rarely carried out for various reasons, such as nursing home policies [70, 71], doubts about the presence of unbearable suffering or the applicability of the advance directive in that situation [71], and opinions of NHPs about the acceptability of euthanasia for patients with dementia or the validity of a request based on an advance directives [70]. Quantitative studies about end-of-life decisions for children indicate that 25 to 50% of pediatricians at some time receive an explicit request for physician assisted dying for children between the age of 1 and 17, and that in the majority of cases the request comes from parents [72, 73]. The actual performance of physician assisted dying in children was rare according to a study of death certificates (2.7% of deaths in children), but in the few cases that were found, it was mostly at the explicit request of the parents (2.0 out of 2.7%) [72].

Theme 3: families’ experiences and grief process after euthanasia and assisted suicide

Ambivalence, exhaustion, difficulty of choosing a date of performance

Several qualitative studies describe how family members struggle with conflicting feelings during euthanasia decision-making. While they wish for the patient’s suffering to end, and regardless of personal views on EAS, they often considered EAS to be too early, or too definitive [9, 34, 35, 44, 74]. Furthermore, several studies describe family members who had been aware of their own exhaustion due to caregiver responsibilities during euthanasia decision-making [9, 35, 38, 44]. For some it had been a reason to stay out of euthanasia decision-making, or to doubt their role in it [38, 44]. For others, euthanasia was seen as a possibility to organize care and to have a fixed end point of care responsibilities [35]. In various other studies, healthcare professionals -- both physicians and others -- describe exhausted family members, emotionally burdened by the course of events at the deathbed [9, 34, 38, 73]. According to healthcare professionals, families’ exhaustion was sometimes projected onto the patient [9, 34] and an appeal for EAS could be just a call for support and clarity [34]. Meanwhile, planning of EAS could cause relief in exhausted family members [9]. However, the activity of collectively picking a date was often described as very difficult and even as overwhelming or absurd [9, 35, 38, 64].

Varying experiences related to the interaction with physicians

Qualitative studies conducted in primary care describe how discussions about euthanasia were a positive experience for family members. The discussion could foster mutual bonds between patient, family and physician, if there was clear communication and respect for all involved [35, 64]. In contrast, other studies mention how family members had great difficulties with the indecisiveness or conflicting messages of physicians about a request for EAS, and how they could feel powerless and not taken seriously as a patient’s representative [34, 47, 73]. Family members were also found to struggle with acting upon a euthanasia advanced directive, which could cause disagreement about whether the state of unbearable suffering had been reached and about who should make the final decision to act upon it [39, 71]. Lastly, a visit by a consulting physician could provoke different experiences as well, ranging from a positive experience because the consultation was seen as a safeguard in the procedure, to negative experiences relating for instance to a negative judgment about the request for EAS [75, 76].

Mainly positive evaluations afterwards

After euthanasia has been performed, positive experiences seem to prevail in bereaved family members, according to both the findings of qualitative and a limited number of quantitative studies [7, 9, 34, 36, 38, 44, 47, 64, 66]. Despite the feelings of grief and loss, many family members mentioned that they felt relieved that the suffering had ended, that the patient’s wish had been fulfilled, and that it had been a peaceful deathbed surrounded by loved ones. In one study, a bereaved daughter and son-in-law directly related their positive experiences with the euthanasia-death of their mother to preferences for their own death in the future [38]. In line with these positive experiences, Swarte et al. found statistically significant less traumatic grief in family and friends after EAS compared to a ‘normal’ death in a cross-sectional study performed in a tertiary oncology center [77]. In this study, cancer patients who died through euthanasia more often had ‘others’ as their social network, such as cousins and friends, than cancer patients who died a natural death, which more often involved partners and first-degree blood relatives. In bereaved partners, family and friends of AIDS patients, no significant association was found between the occurrence of depression after a normal versus a euthanasia-death [74].

Complicated grief after a complicated process

Nevertheless, complicated grief and negative experiences after euthanasia were described as well, relating to a hampered process preceding EAS [38, 47, 68, 74] or to secrecy among close family members about EAS as cause of death [35, 38]. In his 1995 mixed-method study with AIDS patients, Boom found how complicated grief can be due to the responsibility of deciding about the date for EAS, the speed of dying after the lethal injection (extremely fast or prolonged), and the responsibility for administering lethal medication. The latter aspect was mentioned in a case study as well [68]. In addition, in two studies from the nineties, single cases are described of family members who developed psychopathology, or who thought of or actually committed suicide using lethal drugs that were at a patient’s disposal [38, 74]. Furthermore, three qualitative studies investigating family members’ experience after EAS mention how some family members refused to participate in the study due to the sensitivity of the topic or the emotional burden after euthanasia [66, 71, 75].

Theme 4: family and the ‘good euthanasia death’ according to Dutch physicians

Physicians’ experiences with EAS and family involvement

Dutch physicians’ personal experiences with EAS seem to be profoundly influenced by the involvement of family members in both positive and negative ways. This applies especially for GPs. Although EAS was described as heavy and burdening regardless of one’s personal views [38, 47], GPs found comfort and had positive experiences thanks to the support and expressions of gratefulness of bereaved family members [35, 36, 38, 44, 78]. Even the experience of ‘becoming part of the family’ was mentioned in a few studies [35, 38, 47]. At the same time, complexities and negative experiences with EAS for GPs and other physicians were found to relate to the involvement of family members as well. The pressure that family members exerted on the physician, disagreements about the process or the suffering, opposition, lack of open conversation, different expectations and the idea that euthanasia was an enforceable right were described as elements of a complex or negative EAS process [9, 11, 35, 38, 42, 47, 64, 79]. Some consulting physicians had similar negative experiences relating to family pressure [65, 76], and family-related complexities could be a reason for consultation with other GP advisors in palliative care [80]. However, the 2011 survey by Van Delden et al. found that only 13% of participating physicians had negative experiences with pressure exerted by family members during EAS decision-making. Almost 90% of the physicians experienced respect for their position and were able to come to an agreement about the final decision [42].

Taking care of the family as a task

From qualitative studies conducted among GPs, it emerged that many, although not all of them, considered it their task to take care of both patient and family members during euthanasia decision-making [7, 9, 11, 35, 38, 44, 47, 64, 81]. Specific elements of taking care were described, namely establishing good relationships with all involved [11, 35, 38, 64, 81], informing and preparing family members for EAS [35, 38, 47, 64], facilitating contact with estranged family members [35, 38] and taking into account the family members’ future grief process [9, 35, 38]. Some GPs describe how ‘euthanasia-talk’ could have a therapeutic effect for all involved, reducing anxiety and fostering open conversation about death [35, 38]. Similar themes were mentioned in recent interviews with psychiatrists who have experience with EAS [7]. On the other hand, some GPs and other physicians were described who only see taking care of their individual patient as their task [9, 11, 38]. One study on EAS guidelines in nursing homes showed how 75% of these guidelines mention that consultation with or the informing of family members is advised [82]. Studies involving nurses showed that although a minority of nurses is actually involved in EAS decision-making, they often consider it their task to counsel both patient and family members and to provide aftercare for family members [34, 83, 84].

Family support or agreement as additional criterion for EAS

Both earlier and recent qualitative studies among GPs and psychiatrists describe how these physicians considered to forego euthanasia in cases where the family could not cope, where family was absent or if there was a family conflict, despite knowing that these considerations were not related to any legal criterion [7, 11, 12, 35]. Furthermore, in a study investigating physicians’ opinions about EAS for children, GPs and medical specialists less often agreed with the idea of granting EAS for a child without parental consent than pediatricians [85]. Diverging opinions among pediatricians on the extent to which parents should be involved in EAS decision-making for children were found in other studies as well [73, 86].

Reluctance to consider social indications for EAS

Besides family agreement as additional criterion, a reluctance to consider EAS on social indications was found as a theme in both quantitative and qualitative studies, especially in studies with GPs. A vignette-based study found a substantial variation in opinions among GPs whether the suffering in vignettes marked as ‘being a burden’, ‘dependency’ and ‘fear of future suffering’ could be judged as unbearable suffering, with a 88% correspondence with not granting an EAS request [87]. In addition, GPs were significantly less likely to judge fictional cases marked as ‘being a burden’, ‘dependency’ and ‘future decay’ as unbearable suffering compared to consulting physicians and members of review committees, while they mostly agreed on the presence of unbearable suffering in a case marked by acute pain and progressive symptoms due to a physical disorder [88]. Another survey showed how only a minority of GPs would consider granting an EAS request without an underlying somatic or psychiatric disorder [89]. Similarly, qualitative studies described a GP who organized additional care to assure that a request did not originate from the feeling of being a burden [38], as well as GPs and other physicians who found it difficult to empathize with EAS requests based on dependency, loneliness and existential aspects [12, 79]. Snijdewind et al. describe how several, but not all physicians, doubted whether physicians should have a role in such cases and whether these were medical or societal problems [79]. Furthermore, ‘being a burden’ as an important part of unbearable suffering was related to a higher likelihood that consulting physicians took a negative view of the legal criteria [90] and to less willingness on the part of Dutch internists to perform EAS, compared to their counterparts in the US [91]. In addition, a recent study showed how the rejection of patients in the specialized End-of-Life clinic was significantly related to being single or without children, while granted requests were independently associated with having more than one child [92]. A study from 2010 based on death certificates found no association between marital status and refusal of EAS requests [93].

The general public’s opinion on family’s involvement in EAS

In contrast to physicians’ reluctance to consider requests for EAS on social indications, a questionnaire-based study about notions of ‘good ways to die’ among the general public showed how an acceptance of euthanasia was significantly related to reasons like avoiding being a burden on others and dependency, in addition to remaining in control and having a painless death [94]. An earlier questionnaire-based study described more permissive attitudes among relatives compared to physicians regarding (proxy-decision making for) EAS for patients with dementia [95]. At the same time, opinions were divided about whether it was important for family members to be involved in EAS decision-making. An earlier mixed-method study among the general public found instances of fear about bad intentions of family members and concerns about their influence on EAS decision-making [42].

Discussion

The aim of this review was to explore how family members are involved in the Dutch practice of EAS according to existing empirical research, and to map out themes relevant for further research and discussion. The results indicate that a request for EAS can originate from family-related considerations, that family members seem to fulfill demanding roles and responsibilities in EAS decision-making with varying experiences, and that Dutch physicians - especially GPs - seem to show sincere consideration for family members and the broader social context when deciding on a request for EAS. The results of this review offer a new perspective on EAS decision-making in the Netherlands, which is typically framed in the patient-physician dyad. However, a triad model in which family members also have a position seems more appropriate to describe what goes on in clinical practice, as suggested previously by Snijdewind et al. as well [11]. Adopting such a patient-physician-family triad for EAS decision-making brings empirical and ethical questions to attention that have not been sufficiently addressed so far.

Methodological considerations

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of the explorative approach and qualitative method of synthesis used in this review. Due to the heterogeneity of study aims, methods and participants in the included studies, the generalizability of the results is limited. Also, it is particularly challenging to synthesize qualitative studies since the context may partly be lost in the process, while the context is essential for a correct interpretation of the results. Besides, the context of several of the included studies may no longer be comparable to the present-day practice of EAS, which is described in more detail below. Nevertheless, this review raises themes and identifies problems that can serve as a starting point for further empirical and ethical inquiry.

One may criticize the inclusion of studies in which family members themselves weren’t study participants or in which their experiences and roles were not the main subject of inquiry. However, the number of studies with family members as participants was found to be limited (14 out of 66 studies), which may itself be considered a significant result. Additionally, the literature search yielded studies that mentioned patients’ and physicians’ perspectives on and experiences with family members or the broader social context. Since the objective of this review was to explore this underdeveloped field, a broad interpretation of “involvement of family members” was chosen, in order to highlight a wide range of themes that might be relevant for further inquiry and debate.

Implications for empirical research

Question 1: the patient’s family or significant others…who are they, really?

First and foremost, the question is who the patient’s significant others are who could be involved in the present-day practice of EAS in the Netherlands. There is no standardized registration of the people in the social networks of patients who request and receive EAS. For instance, physicians who perform EAS are not required to report this kind of information to the regional euthanasia review committees. In this review, partners and children feature as the most closely involved significant others. However, the composition of families and social networks seems to be changing in the Netherlands, as is the amount of informal care that the state expects the social networks to provide. Therefore, there is a need for up-to-date quantitative data about the social networks surrounding patients who request and receive EAS in the Netherlands, including information about their caregiver responsibilities and burden. This point has been raised by others as well [1, 91]. The physical, emotional and financial burden of family carers in Dutch general practice and the correlation between caregivers’ burden and patients’ symptoms has been studied before, but not in relation to requests for EAS [96,97,98]. Quantitative information about professional caregivers other than physicians who are involved in the care for patients and their families, especially in general practice, would be interesting as well. An important theoretical question underlying this is whether the underrepresentation of the social network as study-object or study participants in empirical research is related to their absence in the Dutch euthanasia law.

Question 2: how important are family-related reasons for EAS?

This review raises the question how important family-related reasons are for Dutch patients who consider requesting euthanasia or assisted suicide, and how this should be studied. A relationship between the wish to hasten death and witnessing the suffering of others [99] or the feeling of being a burden [100] has been reported before. A recent review on the experiences of patients with a wish to hasten death also described how social-relational factors could be a source of suffering and a reason for expressing a wish to hasten death [101]. However, these social factors were among a range of sources of suffering like physical, psychological and existential factors, and among other reasons for and meanings of the wish to hasten death. Still, the results of this review raise some questions. The presence of family-related reasons in qualitative studies contrasts with the relative absence of them in quantitative studies on reasons for EAS, as recounted by physicians. This is perhaps just a consequence of methodological factors such as study type, included patients/cases, or the stage of decision-making. It may also reflect the physicians’ reluctance to perform EAS on social indication. On the other hand, we may wonder whether physicians recognize family-related reasons or social-relational origins of suffering, and whether patients feel free to speak about it when they have an explicit request for EAS. New qualitative studies with ethnographic or narrative approaches could shed light on how requests for EAS develop over time and in mutual interaction between patients, their significant others and professional caregivers. This approach might also be better suited to identify any cultural, political and existential views that may lie behind requests for EAS [102].

Question 3: what about the roles, responsibilities, experiences and grief of the family?

Further in-depth inquiry into the responsibilities and experiences of family members during and after EAS decision-making is necessary. Detailed descriptions of family members’ responsibilities and experiences were mainly found in ethnographies and in-depth interviews from 2009 and before. Some of them were even conducted before the euthanasia law was enacted [9, 34, 38] or were conducted in a hospital [9, 34], while the majority of EAS cases are currently carried out in general practice. Physicians’ practices and the public awareness of EAS have probably changed over the last 20 years. Hence, the interaction between patients, families and physicians during EAS decision-making and related experiences and needs may have changed as well. Furthermore, the quantitative studies on bereavement after EAS included in this review were conducted more than 15 years ago in a hospital setting [74, 77], which is again no longer representative for the majority of cases of EAS nowadays. Empirical studies from the US [103] and Switzerland [104] and grey literature from the Netherlands [105] highlight family members’ ambivalent feelings and demanding tasks when involved in assisted dying, and contrasting findings on grief after assisted dying have been reported [106, 107]. Although these findings resemble the results of this review, further research specific for the Dutch context is needed, such as the work performed by Dees et al. [64], because of differences in legislative frameworks and the pivotal role of general practitioners in the Dutch practice of assisted dying. Future studies could also examine differences in family members’ responsibilities and experiences in cases of euthanasia, compared to physician assisted suicide (PAS) in the Dutch setting. PAS is much rarer than euthanasia in the Netherlands, and interestingly, patients receiving PAS seem affected by psychosocial suffering more frequently than patients receiving euthanasia [108]. In addition, the implications of the use of advance euthanasia directives for both patients, family members and physicians should be explored further. While advance euthanasia directives are receiving steadily more attention in the Dutch public discourse about euthanasia for both patients with somatic as well as patients with dementia, their use in practice seems to be highly problematic [109].

Question 4: what about the ‘good euthanasia death’ according to physicians and others?

Lastly, further research is needed to assess the generalizability of results on physicians’ ideas about the ‘good euthanasia death’ and the consequences thereof for clinical practice. Physicians’ varying ideas about the ‘good euthanasia death’ and any additional criteria they may apply might conflict with the wishes of individual patients and the need for clarity about the procedure for both patients and family members. Since GPs are the physicians who currently perform most of the cases of EAS in the Netherlands, it would be valuable to better understand how GPs see their professional role with regard to EAS, what patients’ and families’ expect of their GP, and whether and how these expectations might diverge. For instance, Snijdewind et al. have already described physicians who wonder whether they are seen as “involved caregivers” or “mere performers of EAS” [79].

Implications for ethical inquiry

Normative conclusions about the involvement of family members in the Dutch practice of EAS would require a thorough examination of ethical arguments on family involvement in medical decision- making and physician assisted dying first, as well as further empirical research as described in the section above. Several scholars have emphasized the moral relevance of family members in medical decision-making, based on the existence of important shared values and interests and the profound influence of family relationships and dynamics on autonomous decision-making and people’s identity [17,18,19, 24, 110,111,112]. One of the major ethical issues is whether the interests of individual patients should always prevail, or that the interests and needs of family members should have equal weight or should at least be acknowledged, especially in end-of-life settings [24, 26, 113]. In addition, others have warned about the importance of family dynamics and interpersonal influences in assisted suicide, whether it is medically assisted or not, and how that could infringe on the patient’s responsibility and choice [114]. A close examination of those arguments and how they relate to the Dutch practice of EAS goes beyond the scope of this paper. Still, important suggestions for further ethical inquiry can already be given based on the results of this review.

The results of this review point to a tangle of needs, experiences and responsibilities of patients, their families and physicians in the practice of EAS. These findings already challenge the current Dutch ethical-legal framework of EAS which is based on autonomy, i.e. the voluntary request of the patient, and compassion, i.e. the relief of suffering by the physician [115]. Situating autonomy and the relief of suffering in the patient-physician-family triad, instead of the patient-physician dyad, draws the attention to specific ethical questions.

One of these questions is how a voluntary request for EAS should be both enabled and safeguarded when family members are closely involved in the process of EAS decision-making. The concept of relational autonomy could help examine the different links between relationality and autonomous choice for EAS [11, 18, 19, 111]. Reciprocal and collaborative aspects of autonomy might come into play in EAS, due to the possibility of choice and planning that is typical of assisted dying in contrast to a natural death [22]. However, the normative consequences of a relational concept of autonomy for the practice of EAS should still be examined and discussed [11, 116]. Further, the use of advance euthanasia directives has already been identified as an important ethical issue [109, 117], but the pivotal role and interests of family members may be overlooked if the focus is merely on the question whether an advance euthanasia directive is a sufficient substitute for a voluntary request or not.

Another question is not only what kind, but also whose suffering may count in an EAS decision-making process. Dutch physicians have traditionally focused on the patient’s physical suffering as the most important ground for EAS [46], a pattern that was found in this review as well. However, this review has also uncovered family-related reasons for EAS. These family-related reasons could be redefined as suffering because of (experiences with/lack of) significant others, but also as efforts to prevent the suffering of others or to create meaning around the deathbed for all parties involved. It has been argued before that suffering is caused by much more than just physical symptoms [118], and that choosing EAS for family-related reasons could attribute meaning to death and could be fully compatible with autonomous decision-making [119, 120]. Given the divergent opinions among physicians and between physicians and the public about the acceptability of family-related or social reasons for EAS, the concept of suffering and its interpersonal and existential dimensions require further critical examination.

Finally, the patient-physician-family triad in the Dutch practice of EAS draws attention to the “social fabric” that lies behind clinical practice and to questions of professional responsibilities, justice and solidarity [17, 121]. Policy changes that affect the functioning of social networks or the resources of informal caregivers may influence the practice of EAS as well. In addition, the growing focus on autonomous choice in the public debate about EAS in the Netherlands seems to affect expectations regarding physicians’ professional duties [122]. Especially GPs have traditionally focused on the interests of both patients and their family in euthanasia decision-making [121], as found in this review as well. The ethical desirability of this role may be questioned: it can be seen as a way to protect the well-being of both patients and family members, but it could also be seen as an inappropriate use of medical power and as an infringement of individual autonomy [115]. Nevertheless, with the patient-physician-family triad in mind, it seems important to carefully assess what the effect on both patients and their families may be, if the responsibilities of physicians in the Dutch practice of EAS were to change. To conclude: it is still far from clear what a ‘good euthanasia-death’ in the Netherlands should look like, for who and according to who.

Conclusions

This systematic mixed studies review shows how family members seem to be thoroughly involved at different levels of the Dutch practice of euthanasia and physician assisted suicide. The results reveal how considerations about family members and the social context appear to carry much weight for both patients and physicians when considering a request for EAS. The review also shows how the active participation of family members in EAS decision-making can cause ambivalent feelings and experiences. The results provide a new perspective on the Dutch practice of euthanasia and assisted suicide and challenge the underlying ethical-legal framework, which is based on the patient-physician dyad and the related concepts of autonomy and relief of suffering. Further empirical and ethical inquiry, as well as professional and public debate about the interpretation of the Dutch euthanasia law is needed. Although this review focused on the practice of physician assisted dying in the Netherlands, lessons can be learned for other countries where legislation on physician assisted dying is being considered or has already been implemented.

Abbreviations

- EAS:

-

Euthanasia and physician assisted suicide

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- DAS:

-

Demedicalized assisted suicide

- NHP:

-

Nursing home physician

- PAD:

-

Physician assisted dying

- PAS:

-

Physician assisted suicide

References

Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J. Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA. 2016;316(1):79–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.8499.

Quill T. Dutch practice of euthanasia and assisted suicide: a glimpse at the edges of the practice. J Med Ethics. 2018;44(5):297–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2018-104759.

Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau. De sociale staat van Nederland 2017. Den Haag, 2017. https://www.scp.nl/Publicaties/Alle_publicaties/Publicaties_2017/De_sociale_staat_van_Nederland_2017. Accessed 23 Jan 2019.

KNMG. The role of the physician in the voluntary termination of life. Utrecht, 2011. https://www.knmg.nl/actualiteit-opinie/nieuws/nieuwsbericht/euthanasia-in-the-netherlands.htm Accessed 23 Jan 2019.

Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Penning C, de Jong-Krul GJF, van Delden JJM, van der Heide A. Trends in end-of-life practices before and after the enactment of the euthanasia law in the Netherlands from 1990 to 2010: a repeated cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2012;380(9845):908–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61034-4.

Marquet RL, Bartelds A, Visser GJ, Spreeuwenberg P, Peters L. Twenty five years of requests for euthanasia and physician assisted suicide in Dutch general practice: trend analysis. BMJ. 2003;327(7408):201–2. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7408.201.

Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Legemaate J, Van der Heide A, Van Delden H, Evenblij K, El Hammoud I, et al. Derde evaluatie Wet Toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding. Den Haag: ZonMw; 2017.

Regional Euthanasia Review Committees. Annual report 2017. The Hague, 2018. https://english.euthanasiecommissie.nl/the-committees/annual-reports. Accessed 18 Jan 2019.

Pool R. Vragen om te sterven: Euthanasie in een Nederlands ziekenhuis. Rotterdam: WYT Uitgeefgroep; 1996.

Kimsma GK, van Leeuwen E. The role of family in euthanasia decision making. HEC Forum. 2007;19(4):365–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-007-9048-z.

Snijdewind MC, van Tol DG, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Willems DL. Complexities in euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide as perceived by Dutch physicians and patients' relatives. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;48(6):1125–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.04.016.

Ten Cate K, van Tol DG, van de Vathorst S. Considerations on requests for euthanasia or assisted suicide; a qualitative study with Dutch general practitioners. Fam Pract. 2017;34(6):723–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmx041.

van Dalen L. Euthanasie — Wat gaat dat de familie eigenlijk aan? Systeemtherapie. 2012;24(2):89–96.

Hudson P, Hudson R, Philip J, Boughey M, Kelly B, Hertogh C. Physician-assisted suicide and/or euthanasia: pragmatic implications for palliative care [corrected]. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(5):1399–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515000176.

Van Tol D, Weyers H, Family Matters. Over de rol van (het lijden van) naasten in situaties van euthanasie en palliatieve sedatie. In: Boer TA, Mul D, editors. Lijden en volhouden. Amsterdam: Buijten & Schipperheijn Motief; 2016. p. 68–80.

Kimsma GK. Death by request in The Netherlands: facts, the legal context and effects on physicians, patients and families. Med Health Care Philos. 2010;13(4):355–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-010-9265-0.

Verkerk MA, Lindemann H, McLaughlin J, Scully JL, Kihlbom U, Nelson J, et al. Where families and healthcare meet. J Med Ethics. 2015;41(2):183–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2013-101783.

Breslin JM. Autonomy and the role of the family in making decisions at the end of life. J Clin Ethics. 2005;16(1):11–9.

van Nistelrooij I, Visse M, Spekkink A, de Lange J. How shared is shared decision-making? A care-ethical view on the role of partner and family. J Med Ethics. 2017;43(9):637–44. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2016-103791.

Hudson P. Improving support for family carers: key implications for research, policy and practice. Palliat Med. 2013;27(7):581–2. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313488855.

Munthe C, Sandman L, Cutas D. Person centred care and shared decision making: implications for ethics, public health and research. Health Care Anal. 2012;20(3):231–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-011-0183-y.

Donchin A. Autonomy, interdependence, and assisted suicide: respecting boundaries/crossing lines. Bioethics. 2000;14(3):187–204.

Belanger E. Shared decision-making in palliative care: research priorities to align care with patients’ values. Palliat Med. 2017;31(7):585–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317713864.

Hardwig J. What about the family? Hast Cent Rep. 1990;20(2):5–10.

Visser M, Deliens L, Houttekier D. Physician-related barriers to communication and patient- and family-centred decision-making towards the end of life in intensive care: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2014;18(6):604. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-014-0604-z.

Cohen-Almagor R. Patients’ right to die in dignity and the role of their beloved people. JRE. 1996;4:213.

Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35(1):29–45. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182440.

Pluye P, Hong QN, Vedel I. Toolkit for mixed studies reviews (V3). Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, and Quebec-SPOR SUPPORT Unit, Montreal, Canada. 2016. http://toolkit4mixedstudiesreviews.pbworks.com. Accessed 24 Oct 2017.

Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, Wassef M. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1):45–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/135581960501000110.

Georges JJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Heide A, van der Wal G, van der Maas PJ. Physicians' opinions on palliative care and euthanasia in the Netherlands. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(5):1137–44. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1137.

Pasman HR, Willems DL, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. What happens after a request for euthanasia is refused? Qualitative interviews with patients, relatives and physicians. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(3):313–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.06.007.

The A-M. ‘Vanavond om 8 uur...’ : verpleegkundige dilemma's bij euthanasie en andere beslissingen rond het levenseinde. Houten etc.: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum; 1997.

Norwood F. The maintenance of life: preventing social death through euthanasia talk and end-of-life care -- lessons from the Netherlands. Ethnographic studies in medical anthroplogy series. Durham, North Carolina: Carolina Academic Press; 2009.

Meyboom-de JB. Active euthanasia. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1983;127(22):946–50.

Booij SJ, Rodig V, Engberts DP, Tibben A, Roos RA. Euthanasia and advance directives in Huntington's disease: qualitative analysis of interviews with patients. J Huntington’s Dis. 2013;2(3):323–30. https://doi.org/10.3233/JHD-130060.

Ciesielski-Carlucci C, Kimsma G. Living with Euthanasia: Physicians and Families speak for Themselves. In: Thomasma DC, Kimbrough-Kushner T, Kimsma G, Ciesielski-Carlucci C, editors. Asking to Die: Inside the Dutch Debate about Euthanasia. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. p. 271–355. 409–81.

Rurup ML, Pasman HR, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Advance euthanasia directives in dementia rarely carried out. Qualitative study in physicians and patients. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde. 2010;154:A1273.

Booij SJ, Tibben A, Engberts DP, Marinus J, Roos RA. Thinking about the end of life: a common issue for patients with Huntington’s disease. J Neurol. 2014;261(11):2184–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-014-7479-4.

Kouwenhoven PS, Raijmakers NJ, van Delden JJ, Rietjens JA, van Tol DG, van de Vathorst S, et al. Opinions about euthanasia and advanced dementia: a qualitative study among Dutch physicians and members of the general public. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-16-7.

van Delden JJ, van der Heide A, van de Vathorst S, Weyers H, van Tol DG. Kennis en opvattingen van publiek en professionals over medische besluitvorming en behandeling rond het einde van het leven: het KOPPEL-onderzoek. The Hague: ZonMW; 2011.

Rurup ML, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Heide A, van der Wal G, Deeg DJ. Frequency and determinants of advance directives concerning end-of-life care in The Netherlands. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(6):1552–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.010.

Ponsioen BP. How does the general practitioner learn to live with euthanasia? Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1983;127(22):961–4.

Dees MK, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Dekkers WJ, Vissers KC, van Weel C. 'Unbearable suffering': a qualitative study on the perspectives of patients who request assistance in dying. J Med Ethics. 2011;37(12):727–34. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2011.045492.

Pasman HR, Rurup ML, Willems DL, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Concept of unbearable suffering in context of ungranted requests for euthanasia: qualitative interviews with patients and physicians. BMJ. 2009;339:b4362. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b4362.

Van der Heide A, Legemaate J, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Bolt E, Bolt I, Van Delden H, et al. Tweede evaluatie Wet Toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding. Den Haag: ZonMw; 2012.

Ruijs CD, Kerkhof AJ, van der Wal G, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Symptoms, unbearability and the nature of suffering in terminal cancer patients dying at home: a prospective primary care study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:201. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-201.

Ruijs CD, van der Wal G, Kerkhof AJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Unbearable suffering and requests for euthanasia prospectively studied in end-of-life cancer patients in primary care. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13(1):62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-13-62.

Maessen M, Veldink JH, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Hendricks HT, Schelhaas HJ, Grupstra HF, et al. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a prospective study. J Neurol. 2014;261(10):1894–901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-014-7424-6.

Jansen-van der Weide MC, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Wal G. Granted, undecided, withdrawn, and refused requests for euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(15):1698–704. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.15.1698.

Abarshi E, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Wal G. Euthanasia requests and cancer types in the Netherlands: is there a relationship? Health Policy. 2009;89(2):168–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.05.014.

Van der Wal G, van Eijk JT, Leenen HJ, Spreeuwenberg C. Euthanasia and assisted suicide. II. Do Dutch family doctors act prudently? Fam Pract. 1992;9(2):135–40.

Verhoef MJ, van der Wal G. Euthanasia in family practice in The Netherlands. Toward a better understanding. Canadian Family Physician Medecin De Famille Canadien. 1997;43:231–7.

Groenewoud JH, Van Der Heide A, Tholen AJ, Schudel WJ, Hengeveld MW, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al. Psychiatric consultation with regard to requests for euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):323–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.004.

Van Der Maas PJ, Van Delden JJ, Pijnenborg L, Looman CW. Euthanasia and other medical decisions concerning the end of life. Lancet (London, England). 1991;338(8768):669–74.

van der Wal G, van Eijk JT, Leenen HJ, Spreeuwenberg C. Euthanasia and assisted suicide by physicians in the home situation. 2. Suffering of the patients. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1991;135(35):1599–603.

Buiting H, van Delden J, Onwuteaka-Philpsen B, Rietjens J, Rurup M, van Tol D, et al. Reporting of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the Netherlands: descriptive study. BMC Med Ethics. 2009;10:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-10-18.

Rurup ML, Muller MT, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Van Der Heide A, Van Der Wal G, Van Der Maas PJ. Requests for euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide from older persons who do not have a severe disease: an interview study. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):665–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/s003329170400399x.

Kim SY, De Vries RG, Peteet JR. Euthanasia and assisted suicide of patients with psychiatric disorders in the Netherlands 2011 to 2014. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(4):362–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2887.

Muller MT, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Wal G, van Eijk J, Ribbe MW. The role of the social network in active euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Public Health. 1996;110(5):271–5.

van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Rurup ML, Buiting HM, van Delden JJ, Hanssen-de Wolf JE, et al. End-of-life practices in the Netherlands under the euthanasia act. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(19):1957–65. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa071143.

Hanssen-de Wolf JE, Pasman HR, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. How do general practitioners assess the criteria for due care for euthanasia in concrete cases? Health Policy. 2008;87(3):316–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.12.009.

Dees MK, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Dekkers WJ, Elwyn G, Vissers KC, van Weel C. Perspectives of decision-making in requests for euthanasia: a qualitative research among patients, relatives and treating physicians in the Netherlands. Palliat Med. 2013;27(1):27–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216312463259.

Ponsioen BP, In’t veld CJ, van den Heuvel GJ, van Binsbergen JJ. The role of the consulting physician in situations of active euthanasia. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1997;141(19):947–50.

Georges JJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Muller MT, Van Der Wal G, Van Der Heide A, Van Der Maas PJ. Relatives’ perspective on the terminally ill patients who died after euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide: a retrospective cross-sectional interview study in the Netherlands. Death Stud. 2007;31(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180600985041.

van der Heide A, Deliens L, Faisst K, Nilstun T, Norup M, Paci E, et al. End-of-life decision-making in six European countries: descriptive study. Lancet (London, England). 2003;362(9381):345–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14019-6.

Koerselman GF. How independent is the modern patient? Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1986;130(45):2017–8.

Miller DG, Kim SYH. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide not meeting due care criteria in the Netherlands: a qualitative review of review committee judgements. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e017628. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017628.

Rurup ML, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Heide A, van der Wal G, van der Maas PJ. Physicians' experiences with demented patients with advance euthanasia directives in the Netherlands. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1138–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53354.x.

de Boer ME, Droes RM, Jonker C, Eefsting JA, Hertogh CM. Advance directives for euthanasia in dementia: how do they affect resident care in Dutch nursing homes? Experiences of physicians and relatives. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(6):989–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03414.x.

Vrakking AM, van der Heide A, Arts WF, Pieters R, van der Voort E, Rietjens JA, et al. Medical end-of-life decisions for children in the Netherlands. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(9):802–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.159.9.802.

Bolt EE, Flens EQ, Pasman HR, Willems D, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Physician-assisted dying for children is conceivable for most Dutch paediatricians, irrespective of the patient's age or competence to decide. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 2017;106(4):668–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13620.

van den Boom FM. AIDS, euthanasia and grief. AIDS Care. 1995;7(Suppl. 2):S175–85.

Jansen-van der Weide MC, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Heide A, Wal G. How patients and relatives experience a visit from a consulting physician in the euthanasia procedure: a study among relatives and physicians. Death Stud. 2009;33(3):199–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180802672272.

Buiting H, Willems D, Rurup M, Pasman R, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. Support and consultation for euthanasia: evaluation of SCEN. [Dutch]. Huisarts en Wetenschap. 2011;54(4):198–202.

Swarte NB, van der Lee ML, van der Bom JG, van den Bout J, Heintz AP. Effects of euthanasia on the bereaved family and friends: a cross sectional study. BMJ. 2003;327(7408):189. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7408.189.

van Marwijk H, Haverkate I, van Royen P, The AM. Impact of euthanasia on primary care physicians in the Netherlands. Palliat Med. 2007;21(7):609–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216307082475.

Snijdewind MC, van Tol DG, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Willems DL. Developments in the practice of physician-assisted dying: perceptions of physicians who had experience with complex cases. J Med Ethics. 2018;44(5):292–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2016-103405.

van Heest FB, Finlay IG, Kramer JJ, Otter R, Meyboom-de JB. Telephone consultations on palliative sedation therapy and euthanasia in general practice in The Netherlands in 2003: a report from inside. Fam Pract. 2009;26(6):481–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmp069.

Georges JJ, The AM, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Wal G. Dealing with requests for euthanasia: a qualitative study investigating the experience of general practitioners. J Med Ethics. 2008;34(3):150–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2007.020909.

Haverkate I, Muller MT, Cappetti M, Jonkers FJ, van der Wal G. Prevalence and content analysis of guidelines on handling requests for euthanasia or assisted suicide in Dutch nursing homes. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(3):317–22.

van Bruchem-van de Scheur GG, van der Arend AJ, Spreeuwenberg C, Abu-Saad HH, ter Meulen RH. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the Dutch homecare sector: the role of the district nurse. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58(1):44–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04224.x.

de Veer AJ, Francke AL, Poortvliet EP. Nurses’ involvement in end-of-life decisions. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(3):222–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000305724.83271.f9.

Vrakking AM, van der Heide A, Looman CW, van Delden JJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Maas PJ, et al. Physicians’ willingness to grant requests for assistance in dying for children: a study of hypothetical cases. J Pediatr. 2005;146(5):611–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.044.

Vrakking AM, van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G. Regulating physician-assisted dying for minors in the Netherlands: views of paediatricians and other physicians. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 2007;96(1):117–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.00004.x.

van Tol D, Rietjens J, van der Heide A. Judgment of unbearable suffering and willingness to grant a euthanasia request by Dutch general practitioners. Health Policy. 2010;97(2–3):166–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.04.007.

Rietjens JA, van Tol DG, Schermer M, van der Heide A. Judgement of suffering in the case of a euthanasia request in The Netherlands. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(8):502–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2008.028779.

Rurup ML, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Van Der Wal G. A “suicide pill” for older people: attitudes of physicians, the general population, and relatives of patients who died after euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide in The Netherlands. Death Stud. 2005;29(6):519–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180590962677.

Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Vergouwe Y, van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Obligatory consultation of an independent physician on euthanasia requests in the Netherlands: what influences the SCEN physicians judgment of the legal requirements of due care? Health Policy. 2014;115(1):75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.12.002.

Willems DL, Daniels ER, van der Wal G, van der Maas PJ, Emanuel EJ. Attitudes and practices concerning the end of life: a comparison between physicians from the United States and from The Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(1):63–8.

Snijdewind MC, Willems DL, Deliens L, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Chambaere K. A study of the first year of the end-of-life Clinic for Physician-Assisted Dying in the Netherlands. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1633–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3978.

Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Rurup ML, Pasman HR, van der Heide A. The last phase of life: who requests and who receives euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide? Med Care. 2010;48(7):596–603. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181dbea75.

Rietjens JA, van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G. Preferences of the Dutch general public for a good death and associations with attitudes towards end-of-life decision-making. Palliat Med. 2006;20(7):685–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216306070241.

Rurup ML, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Pasman HR, Ribbe MW, van der Wal G. Attitudes of physicians, nurses and relatives towards end-of-life decisions concerning nursing home patients with dementia. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(3):372–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.04.016.

De Korte-Verhoef MC, Pasman HR, Schweitzer BP, Francke AL, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Deliens L. Burden for family carers at the end of life; a mixed-method study of the perspectives of family carers and GPs. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13(1):16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684x-13-16.

Pivodic L, Van den Block L, Pardon K, Miccinesi G, Vega Alonso T, Boffin N, et al. Burden on family carers and care-related financial strain at the end of life: a cross-national population-based study. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(5):819–26.