Abstract

Background

The PERMA Model, as a positive psychology conceptual framework, has increased our understanding of the role of Positive emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Achievements in enhancing human potentials, performance and wellbeing. We aimed to assess the utility of PERMA as a multidimensional model of positive psychology in reducing physician burnout and improving their well-being.

Methods

Eligible studies include peer-reviewed English language studies of randomized control trials and non-randomized design. Attending physicians, residents, and fellows of any specialty in the primary, secondary, or intensive care setting comprised the study population. Eligible studies also involved positive psychology interventions designed to enhance physician well-being or reduce physician burnout. Using free text and the medical subject headings we searched CINAHL, Ovid PsychINFO, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar (GS) electronic bibliographic databases from 2000 until March 2020. We use keywords for a combination of three general or block of terms (Health Personnel OR Health Professionals OR Physician OR Internship and Residency OR Medical Staff Or Fellow) AND (Burnout) AND (Positive Psychology OR PERMA OR Wellbeing Intervention OR Well-being Model OR Wellbeing Theory).

Results

Our search retrieved 1886 results (1804 through CINAHL, Ovid PsychINFO, MEDLINE, and 82 through GS) before duplicates were removed and 1723 after duplicates were removed. The final review included 21 studies. Studies represented eight countries, with the majority conducted in Spain (n = 3), followed by the US (n = 8), and Australia (n = 3). Except for one study that used a bio-psychosocial approach to guide the intervention, none of the other interventions in this review were based on a conceptual model, including PERMA. However, retrospectively, ten studies used strategies that resonate with the PERMA components.

Conclusion

Consideration of the utility of PERMA as a multidimensional model of positive psychology to guide interventions to reduce burnout and enhance well-being among physicians is missing in the literature. Nevertheless, the majority of the studies reported some level of positive outcome regarding reducing burnout or improving well-being by using a physician or a system-directed intervention. Albeit, we found more favorable outcomes in the system-directed intervention. Future studies are needed to evaluate if PERMA as a framework can be used to guide system-directed interventions in reducing physician burnout and improving their well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Physician mental health burnout is a public health problem in the United States [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Physician burnout is associated with negative consequences, such as physician-reported error [11] medication error, [12, 13] suicide, [1, 14] substance abuse, [15] sick leave, [16] physician turnover, [17] decreases in best practice, reduction in physician empathy, lower patient satisfaction, reduced health outcome, and increase cost [18] among the others. The system-related drivers of physician burnout include meaningless excessive workload, [19] work-home conflicts, [20] hours worked at nights on call, [21] and a negative work environment. [22] Individual related factors such as personality, interpersonal skills, and coping behaviors are also responsible. [23] It is evident that addressing physician burnout may benefit from a multi-dimensional approach, in which both physicians and the system are responsible for developing thoughtful solutions that consider the drivers of burnout. [10, 24, 25].

The advocates of positive psychology (PI) have voiced the need for a new paradigm to approach burnout. [26, 27] A ground-breaking approach, positive psychology utilizes optimum human potentials, strengths, and functioning to allow individuals to thrive. [28, 29] The positive psychology approach specifically focuses on the constructs of feeling good and functioning well, including hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. [30,31,32,33] Positive psychology interventions target mechanisms of feelings, thoughts, and behavior via strategies such as gratefulness, savoring, mindfulness, acts of kindness, forgiveness, meaningful activities to achieve positive health and wellbeing. [34,35,36,37] Similarly, Seligman has conceptualized psychological wellbeing within the Positive emotion (focusing on optimistic perspectives in endeavors and relationships), Engagement (participation in enjoyable activates that stretches the intellect, skills, and emotional capacities), Relationships (fostering meaningful social connections), Meaning (utilization of logic, religion, and spirituality to find the impact of endeavors to self and society that leads to purposeful living), and Accomplishments (accompaniment of goals and recognition to develop a sense of fulfillment) (PERMA). This model of wellbeing provides a framework to promote understanding of the elements that can be targeted to maximize life satisfaction and creativity. [29, 38] According to Seligman, the PERMA model, provides a framework based on which individuals can realize their core strengths and uniqueness to strive to achieve optimal functioning. [28, 29, 32] Studies examining PERMA domains reveal improvements in life satisfaction and creativity, protection against stress, [39] augmented wellbeing, [40] and reduction in depressive symptoms, [37] as well as decreased job burnout.[41] Others have reported a positive association between PERMA’s components and productivity and happiness at work. [42] Additionally, the number of published studies applying PERMA to improve the elements of feeling good and functioning well among nurses and college students has rapidly increased. [31, 43].

The existing literature on allied health professionals indicates the PERMA framework may offer a useful foundation to develop proactive interventions to address physician well-being. However, the value of PERMA as a conceptual framework to reduce physician burnout or improve physician well-being has not been systematically evaluated. To address this gap, we conducted a systematic review to characterize the contribution and outcome of the PERMA conceptual framework in interventional studies aiming to improve physician well-being. Our findings may benefit in the aim of developing interventions targeted to reduce burnout and improve well-being among physicians.

Methods

Data source and literature searches

We reported a systematic review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We developed our search strategy with an expert librarian (JS). He ran two separate searches in Ovid PsychINFO, separating terms within each group with an “OR.” He combined those two searches in a third search where both group of concepts were combined with “AND.” Conceptually the search was the same as the PubMed search, but we reported the results in the Supplementary Table 1 using Ovid’s syntax for a combination of two general or block of terms (Health Personnel OR Health Professionals OR Physician OR Internship and Residency OR Medical staff Or Fellow) AND (Burnout) AND (Positive Psychology OR PERMA OR Wellbeing Intervention OR Well-being Model OR Wellbeing Theory). Using free text and controlled vocabulary we searched CINAHL, Ovid PsychINFO, and MEDLINE, from 2000 until March 2020. We searched the CINAHL with Full-Text database using the EBSCOhost Research Platform. We used the Ovid research platform to search the PsychINFO database. For searches conducted in Ovid PsycINFO, we identified index terms in the Ovid thesaurus and included narrower terms to create a more comprehensive search. Filters were applied to all searches, limiting the date range from 2000 to 2020. We did not apply the English language filter during the search stage. To improve the comprehensiveness of the search, we supplemented the search by adding Google Scholar (GS).[44] We used a combination of the aforementioned key terms. For example, we queried for: Positive Psychology OR PERMA OR Wellbeing Intervention OR Well-being Model OR Wellbeing Theory. The GS search engine uses stemming technology, which morphologically correlates similar words to match documents with different forms of the same word [45], as a result our research yielded approximately 16,000 items (February 2020). [46] We used a stop policy by limiting our search to the first 300 hits sorted by relevance, to better manage the massive results. Additionally, we searched the references of the eligible studies and included relevant studies as well as relevant systematic reviews found from screening reference lists of eligible studies. A review protocol was registered a priori through PROSPERO (CRD205059). No funding was received.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies include peer-reviewed English language studies of randomized control trials and non-randomized design. Attending physicians, residents, and fellows of any specialty in the primary, secondary, or intensive care setting comprised the study population. Eligible studies, also, involved positive psychology interventions designed to enhance physician well-being or reduce physician burnout.

Exclusion criteria

Interventional studies not focusing on physician well-being or burnout from positive psychology perspectives were excluded. We also excluded studies that focused on medical students, as well those not published in peer-review journals, including gray literature.

Study selection

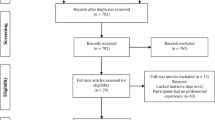

Once we merged research results in a citation manger software, Endnote (X9; Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA) (Fig. 1), we removed duplicates. The remaining articles were shared by three members of the research team (KD, AS, RM) via an online shared folder. The screening process was conducted in two steps. First, members of the research team independently screened the titles and abstracts and selected relevant studies. We considered studies relevant at this stage if they included positive psychology, enhancing wellbeing or wellness, mitigating/reducing burnout terms in their title, or physician wellness or wellbeing in the study abstract or keywords. Second, the selected abstracts were reviewed and validated with another reviewer with content expertise (SB). The full texts of the potentially relevant reports were retrieved and screened by all study team members for final inclusion based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. To do this, the Liberian (JS) exported all articles from the database to the EndNote reference management system. He created three copies of the EndNote references and distributed them to the three reviewers. Each reviewer worked on her/his copy of the EndNote file. In the first reviewing round, the reviewers independently read titles and abstracts to decide whether a reference is potentially relevant to the study. Each reviewer created an ‘Includes’ and ‘Excludes’ folder in their EndNote library and placed the respective references from the general reference list into either of these folders. In the next step, the reviewers compared included references with each other. After consensus was reached, the full texts of the included titles and abstracts were reviewed by each reviewer independently, working on their copies of the EndNote library. After reading all articles, each reference in the library was discussed in detail to gain consensus.

During all screening steps, disagreements among the reviewers were discussed and reconciled (k = 0.73, substantial agreement).

Data extraction and synthesis

Reviewers (AW, NS, KK) independently abstracted data and completed risk of bias assessments from the included studies into a Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet (V2016; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and validated with another reviewer with content expertise (SB). Improved physician well-being articles were summarized according to the authors, the country where the study was conducted, study design, number of participants, participant clinical title (attending or resident), medical specialty, risk of bias (low-high), and the quality grade (A-E). The risk of bias for each included study was determined by adapting designations from the RoB 2 tool for the risk of bias in study designs. [47] The quality grade was determined by adapting grades detailed by [48] that are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Included studies were also summarized according to the study aim, intervention, intervention level (physician or organization level), intervention domain, wellbeing conceptualization domain (physical, mental, work, social) application of PERMA, and the beneficiary of study intervention (intervention, control, none, both). Any disagreements in data abstraction, risk of bias assessments, and synthesis were resolved through discussion (k = 0.88, almost perfect agreement).

Analytical plan

Our analytical approach focused on the contribution of the PERMA model and its components as the underlying theoretical framework to inform the selected study interventions. Study characteristics were summarized as counts, range, and proportions. Study aims and interventional components were interpreted and descriptively summarized. Scoring agreements were expressed as a weighted Cohen’s Kappa coefficient (k = < 0.20 as slight, 0.21–0.40 as fair, 0.41–0.60 as moderate, 0.61–0.80 as substantial, and > 0.81 as almost perfect agreement). When appropriate Stata/IC (v16.1; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) statistical software was used for all quantitative analyses.

Results

Our search retrieved 1886 results (1804 through CINAHL, Ovid PsychINFO, MEDLINE, and 82 through GS) before duplicates were removed and 1723 after duplicates were removed. Of the 1723 references, 1660 were excluded. Ultimately 63 full-text articles were evaluated, and 21 studies met final inclusion (Fig. 1). The full-text studies exclusively targeted reducing physician burnout, stress or enhancing physician well-being by using positive psychology interventions (Table 1). Studies represented eight countries, with the majority conducted in the US (n = 8), followed by Spain (n = 3), and Australia (n = 3). Of the 21 net studies, 18 were randomized control trials, and three studies were non-randomized. The number of participants in each study ranged in size: 1–50 (n = 8), 51–100 (n = 5), 100+ (n = 8). While most participants were attendings (n = 13), seven studies delineated the medical specialty of the attendings: primary care (n = 6), internal medicine (n = 4), and pediatrics (n = 3). Overall, studies had low-risk bias (n = 17) and were of grade A scientific quality (n = 17).

As reflected in Table 2, the majority of the interventions were physician-directed (n = 13) and eight targeted the system within which physicians practiced, and only one study intervened with both the physician and the system. System-directed interventions targeted work hour schedule, staffing, and workload to reduce burnout. [49],[50],[51],[51,52,53,54,55] Of the physician-directed interventions five studies utilized mindfulness exercises, [56,57,58,59,60] six utilized some types of group activities such as debriefing sessions, [61] group discussion, [57, 62, 63] and team-based. [64] Eight studies involved some sort of individualized practice in reducing burnout or to enhance well-being including exercise, [57, 64] role-play, [63] self-care activities, [65,66,67], and communication skill training. [52, 68] Of ten studies demonstrating favorable outcome (statistically significant findings benefiting the intervention group), six were system-directed intervention, and four were physician-direct intervention. Eleven studies reported no statistically significant results, of which three implemented system-directed intervention and eight implemented physician-directed intervention. One study incorporated both system and physician directed intervention and reported positive outcomes. [60] Except Margalit, et al., [63] who used a bio-psychosocial approach to guide their intervention, none of the other interventions in this review were based on a conceptual model, including PERMA. However, retrospectively,10 studies used strategies that resonate with the PERMA components. For example seven studies used mindfulness strategies to improve positive emotion (n = 7), [56,57,58,59,60] and four studies used physician-related or system-related strategies to enhance participant meaningfulness in work, engagement in work, and professional supporting relationship (n = 4) [59,60,61, 67] to reduce burnout or enhance well-being.

Our data reflects that reducing burnout from the perspective of positive psychology has gained momentum and validity among international scholars as it has been in the U.S. However, the use of physician-based and system-based intervention to overcome burnout by various studies speaks of continuous disputes around viewing burnout as a physician-related syndrome or work-setting-related phenomenon, supporting other empirical evidence. [69] Additionally, burnout seems to be an issue despite variability in the work ethic and culture in the high-income countries we covered in this review. This brings in mind the significance of this issue in low to middle-income countries with large health services demands. This scarcity in data demands more burnout related data from these. [70].

Discussion

In this systematic review, we aimed to characterize studies using interventions within the PERMA framework to ameliorate burnout and improve physician well-being. While the interventions in these studies used strategies that resonate with PERMA elements (i.e., to enhancing participant positive emotion, engagement, positive relation, meaning, and accomplishment) the interventions were not guided by any conceptual framework, including the PERMA. Of the 21 studies, only one used a theoretical-based intervention, where bio-psychosocial approach components were added to the intervention. [63] Other studies targeted participant burnout or well-being by exposing them to positive physical, mental, work, and/or social experiences. In the majority of the studies, participants experienced some level of positive perceptions. They were conceptualized as satisfaction with one’s job, finding meaning in one’s job, staying engaged while at work, experiencing work-life balance, less emotional exhaustion, positive attitude, and improving coping and communication skills as a proxy for professional well-being. [37, 71] However, system-directed interventions produced more favorable results compared to physician-directed interventions.

While theoretical models provide valuable guidance in the developing, implementing, evaluating, and success of novel interventions. [72] [73] [74] [75] [76] our review demonstrates that the use of conceptual frameworks in intervention studies implemented in the healthcare setting is limited, as reported before. [73] [77] The Medical Research Council also argues that interventions grounded in theory are more likely to be effective than those that are solely empirical or pragmatic, as theory helps to understand why failures arise and to identify change mechanisms for improvement purposes. [78] [74, 79].

The recently updated definition of professional burnout by the World Health Organization (WHO) considers burnout a work-related syndrome with ICD-11 (International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revisions) code of QD85.[80] According to WHO, burnout is characterized by; 1) experiencing a state of exhaustion, 2) increased negativism or cynicism toward one’s job, and 3) perceived low self-efficacy and achievement in once profession.[80] Several components of the PERMA conceptual framework address system-directed intervention that values enabling individuals to thrive, engage, commit, and find meaning in their professions at the personal and organizational level, which are a common proxy for professional well-being, and contrary to experiencing burnout. [81,82,83] More specifically, the values of finding meaning and purpose in work, in promoting engagement, creativity, and commitment to patient care, were evident in our review, [60] and supported by other empirical studies. [84,85,86].

To further advance positive psychology’s contributions in mitigating physician burnout, there is a need to identify predictive model that can envisage the underlying mechanism that keeps clinicians motivated, engaged, and productive. While there is no generally agreed-upon definition of professional well-being,[87] examining the efficacy of PERMA elements regarding the attainment of clinician well-being within a system-directed approach could fill the existing empirical gap.

This study has several limitations. Our search does not include Web of Science or Scopus, which could have limited our findings. The inclusion of only a subgroup of positive psychology interventions may have excluded pertinent studies or resulted in selection bias. Additionally, we admit that the significant numbers of articles published in languages other than English contribute to the development of this topic, but due to the inability of the research team, we could not access and evaluate them. In addition, due to the heterogeneity of the interventions and their implementation in varying healthcare settings and departments, a meta-analysis was not performed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, consideration of the utility of PERMA as a multidimensional model of positive psychology to guide interventions to reduce burnout and enhance well-being among physicians is missing in the literature. Nevertheless, the majority of the studies reported some level of positive outcome regarding reducing burnout or improving well-being by using a physician or a system-directed intervention. Albeit, we found more favorable outcomes in system-directed intervention. Our finding highlights the research paucity in incorporating conceptual models in the design and implementation of positive psychology interventions to mitigate physician burnout. Future studies are needed to evaluate how PERMA as a framework can disentangle individual from interpersonal and institutional levels of analysis and impact (e.g., self-care from group activities in the physician-directed domain, and work or material from social conditions in the systems-directed domain).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443–51.

Yates M, Samuel V. Burnout in oncologists and associated factors: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2019;28(3):1–19.

Tawfik DS, Profit J. Provider burnout: implications for our perinatal patients. Semin Perinatol. 2020;151243.

Sotile WM, Fallon RS, Simonds GR. Moving from physician burnout to resilience. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62(3):480–90.

Slavin S, Shoss M, Broom MA. A program to prevent burnout, depression, and anxiety in first-year pediatric residents. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(4):456–8.

de Oliveira GS, Jr., Chang R, Fitzgerald PC, Almeida MD, Castro-Alves LS, Ahmad S, et al. The prevalence of burnout and depression and their association with adherence to safety and practice standards: a survey of United States anesthesiology trainees. Anesth Analg. 2013;117(1):182–93.

Blanchard P, Truchot D, Albiges-Sauvin L, Dewas S, Pointreau Y, Rodrigues M, et al. Prevalence and causes of burnout amongst oncology residents: a comprehensive nationwide cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(15):2708–15.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB, Schwab RL. Maslach burnout inventory: consulting psychologists press Palo Alto, CA; 1986.

Campbell DA Jr, Sonnad SS, Eckhauser FE, Campbell KK, Greenfield LJ. Burnout among American surgeons. Surgery. 2001;130(4):696–705.

Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH, editors. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clinic Proceedings; 2017: Elsevier.

Williams ES, Manwell LB, Konrad TR, Linzer M. The relationship of organizational culture, stress, satisfaction, and burnout with physician-reported error and suboptimal patient care: results from the MEMO study. Health Care Manag Rev. 2007;32(3):203–12.

Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, Sharek PJ, Lewin D, Chiang VW, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. Bmj. 2008;336(7642):488–91.

Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995–1000.

Schernhammer E. Taking their own lives -- the high rate of physician suicide. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2473–6.

Oreskovich MR, Kaups KL, Balch CM, Hanks JB, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2012;147(2):168–74.

Toppinen-Tanner S, Ojajärvi A, Väänaänen A, Kalimo R, Jäppinen P. Burnout as a predictor of medically certified sick-leave absences and their diagnosed causes. Behav Med. 2005;31(1):18–32.

Eugene Fibuch M, Arif AB. Physician turnover: a costly problem. Physician Leadership Journal. 2015;2(3):22.

Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2014;12(6):573–6.

Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Hasan O, Satele D, Sloan J, et al., editors. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clinic Proceedings; 2016: Elsevier.

Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Work/home conflict and burnout among academic internal medicine physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1207–9.

Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye L, Sloan JA, Russell TR, Bechamps GJ, et al. Surgeon distress as calibrated by hours worked and nights on Call. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(5):609–19.

Shanafelt TD, Gorringe G, Menaker R, Storz KA, Reeves D, Buskirk SJ, et al., editors. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clinic Proceedings; 2015: Elsevier.

McManus I, Keeling A, Paice E. Stress, burnout and doctors' attitudes to work are determined by personality and learning style: a twelve year longitudinal study of UK medical graduates. BMC Med. 2004;2(1):29.

Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1714–21.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516–29.

Slavin SJ, Schindler D, Chibnall JT, Fendell G, Shoss M. PERMA: a model for institutional leadership and culture change. Acad Med. 2012;87(11):1481.

Slavin SJ, Hatchett L, Chibnall JT, Schindler D, Fendell G. Helping medical students and residents flourish: a path to transform medical education. Acad Med. 2011;86(11):e15.

Seligman ME. Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being: Simon and Schuster; 2012.

Csikszentmihalyi M, Seligman ME. Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):5–14.

Fleming AW. Positive psychology" three good things in life" and measuring happiness. Optimism/Hope, and Well-Being: Positive and Negative Affectivity; 2006.

Donaldson SI, Dollwet M, Rao MA. Happiness, excellence, and optimal human functioning revisited: examining the peer-reviewed literature linked to positive psychology. J Posit Psychol. 2015;10(3):185–95.

Seligman M. Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment: authentic happiness. New York: Free Press; 2002.

Ryff CD. Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(1):10–28.

Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, Pek J, Finkel SM. Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(5):1045–62.

Hendriks T, Schotanus-Dijkstra M, Hassankhan A, Graafsma TGT, Bohlmeijer E, de Jong J. The efficacy of positive psychological interventions from non-western countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Wellbeing. 2018;8(1).

Lomas T, Medina JC, Ivtzan I, Rupprecht S, Eiroa-Orosa FJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on the well-being of healthcare professionals. Mindfulness. 2019;10(7):1193–216.

Gander F, Proyer RT, Ruch W. Positive psychology interventions addressing pleasure, engagement, meaning, positive relationships, and accomplishment increase well-being and ameliorate depressive symptoms: a randomized. Placebo-Controlled Online Study Front Psychol. 2016;7:686.

Seligman M. Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Policy. 2011;27(3):60–1.

Roncaglia I. The role of wellbeing and wellness: a positive psychological model in supporting young people with ASCs. Psychological Thought. 2017;10(1):217–26.

Giannopoulos VL, Vella-Brodrick DA. Effects of positive interventions and orientations to happiness on subjective well-being. J Posit Psychol. 2011;6(2):95–105.

Shaghaghi F, Abedian Z, Forouhar M, Esmaily H, Eskandarnia E. Effect of positive psychology interventions on psychological well-being of midwives: a randomized clinical trial. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8:160.

Robertson I, Cooper C. Well-being: productivity and happiness at work: springer; 2011.

da Camara N, Hillenbrand C, Money K. Putting positive psychology to work in organisations. Journal of General Management. 2009;34(3).

Piasecki J, Waligora M, Dranseika V. Google search as an additional source in systematic reviews. Sci Eng Ethics. 2018;24(2):809–10.

Uyar A. Google stemming mechanisms. J Inf Sci. 2009;35(5):499–514.

Sterne JA, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. bmj. 2019;366.

Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference/William R. Shedish, Thomas D. Cook, Donald T. Campbell: Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 2002.

Garland A, Roberts D, Graff L. Twenty-four-hour intensivist presence: a pilot study of effects on intensive care unit patients, families, doctors, and nurses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(7):738–43.

Ali NA, Hammersley J, Hoffmann SP, O'Brien JM Jr, Phillips GS, Rashkin M, et al. Continuity of care in intensive care units: a cluster-randomized trial of intensivist staffing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(7):803–8.

Ripp JA, Bellini L, Fallar R, Bazari H, Katz JT, Korenstein D. The impact of duty hours restrictions on job burnout in internal medicine residents: a three-institution comparison study. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):494–9.

Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, Varkey A, Yale S, Williams E, et al. A cluster randomized trial of interventions to improve work conditions and clinician burnout in primary care: results from the healthy work place (HWP) study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1105–11.

Lucas BP, Trick WE, Evans AT, Mba B, Smith J, Das K, et al. Effects of 2- vs 4-week attending physician inpatient rotations on unplanned patient revisits, evaluations by trainees, and attending physician burnout: a randomized trial. Jama. 2012;308(21):2199–207.

Shea JA, Bellini LM, Dinges DF, Curtis ML, Tao Y, Zhu J, et al. Impact of protected sleep period for internal medicine interns on overnight call on depression, burnout, and empathy. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(2):256–63.

Parshuram CS, Amaral AC, Ferguson ND, Baker GR, Etchells EE, Flintoft V, et al. Patient safety, resident well-being and continuity of care with different resident duty schedules in the intensive care unit: a randomized trial. Cmaj. 2015;187(5):321–9.

Amutio A, Martínez-Taboada C, Delgado LC, Hermosilla D, Mozaz MJ. Acceptability and effectiveness of a long-term educational intervention to reduce Physicians' stress-related conditions. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2015;35(4):255–60.

Asuero AM, Queraltó JM, Pujol-Ribera E, Berenguera A, Rodriguez-Blanco T, Epstein RM. Effectiveness of a mindfulness education program in primary health care professionals: a pragmatic controlled trial. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2014;34(1):4–12.

Montero-Marin J, Gaete J, Araya R, Demarzo M, Manzanera R. Alvarez de Mon M, et al. impact of a blended web-based mindfulness programme for general practitioners: a pilot study. Mindfulness. 2018;9(1):129–39.

Verweij H, Waumans RC, Smeijers D, Lucassen PL, Donders AR, van der Horst HE, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for GPs: results of a controlled mixed methods pilot study in Dutch primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(643):e99–105.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, Call TG, Davidson JH, Multari A, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527–33.

Gunasingam N, Burns K, Edwards J, Dinh M, Walton M. Reducing stress and burnout in junior doctors: the impact of debriefing sessions. Postgrad Med J. 2015;91(1074):182–7.

Axisa C, Nash L, Kelly P, Willcock S. Burnout and distress in Australian physician trainees: evaluation of a wellbeing workshop. Australasian Psychiatry. 2019;27(3):255–61.

Margalit AP, Glick SM, Benbassat J, Cohen A, Katz M. Promoting a biopsychosocial orientation in family practice: effect of two teaching programs on the knowledge and attitudes of practising primary care physicians. Med Teach. 2005;27(7):613–8.

Weight CJ, Sellon JL, Lessard-Anderson CR, Shanafelt TD, Olsen KD, Laskowski ER. Physical activity, quality of life, and burnout among physician trainees: the effect of a team-based, incentivized exercise program. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1435–42.

Martins AE, Davenport MC, Del Valle MP, Di Lalla S, Domínguez P, Ormando L, et al. Impact of a brief intervention on the burnout levels of pediatric residents. J Pediatr. 2011;87(6):493–8.

Milstein JM, Raingruber BJ, Bennett SH, Kon AA, Winn CA, Paterniti DA. Burnout assessment in house officers: evaluation of an intervention to reduce stress. Med Teach. 2009;31(4):338–41.

Dyrbye LN, West CP, Richards ML, Ross HJ, Satele D, Shanafelt TD. A randomized, controlled study of an online intervention to promote job satisfaction and well-being among physicians. Burn Res. 2016;3(3):69–75.

Bragard I, Etienne AM, Merckaert I, Libert Y, Razavi D. Efficacy of a communication and stress management training on medical residents' self-efficacy, stress to communicate and burnout: a randomized controlled study. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(7):1075–81.

Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131–50.

Sla B. Physician burnout: a global crisis. Lancet. 2016;388(10193):2272–81.

Chari R, Chang C-C, Sauter SL, Sayers ELP, Cerully JL, Schulte P, et al. Expanding the paradigm of occupational safety and health a new framework for worker well-being. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(7):589.

Boudreaux ED, Cydulka R, Bock B, Borrelli B, Bernstein SL. Conceptual models of health behavior: research in the emergency care settings. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(11):1120–3.

Gabriel EH, McCann RS, Hoch MC. Use of social or behavioral theories in exercise-related injury prevention program research: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2019;49(10):1515–28.

Gielen AC, Sleet D. Application of behavior-change theories and methods to injury prevention. Epidemiol Rev. 2003;25(1):65–76.

McGlashan AJ, Finch CF. The extent to which Behavioural and social sciences theories and models are used in sport injury prevention research. Sports Med. 2010;40(10):841–58.

Michie S, Abraham C. Interventions to change health behaviours: evidence-based or evidence-inspired? Psychol Health. 2004;19(1):29–49.

Painter JE, Borba CPC, Hynes M, Mays D, Glanz K. The use of theory in health behavior research from 2000 to 2005: a systematic review. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(3):358–62.

Albarracín D, Gillette JC, Earl AN, Glasman LR, Durantini MR, Ho M-H. A test of major assumptions about behavior change: a comprehensive look at the effects of passive and active HIV-prevention interventions since the beginning of the epidemic. Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):856–97.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(5):587–92.

World Health Organization. Burn-out an "occupational phenomenon": International Classification of Diseases 2019 [Available from: http://id.who.int/icd/entity/129180281

Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB. Defining and measuring work engagement: bringing clarity to the concept. Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research. 2010;12:10–24.

Schaufeli W, Bakker AB. The conceptualization and measurement of work engagement; 2010.

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397–422.

Tak HJ, Curlin FA, Yoon JD. Association of intrinsic motivating factors and markers of physician well-being: a national physician survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(7):739–46.

Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC, editors. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clinic Proceedings; 2017: Elsevier.

Shanafelt TD. Enhancing meaning in work: a prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. Jama. 2009;302(12):1338–40.

Brady KJ, Trockel MT, Khan CT, Raj KS, Murphy ML, Bohman B, et al. What do we mean by physician wellness? A systematic review of its definition and measurement. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(1):94–108.

Holt J, Del Mar C. Reducing occupational psychological distress: a randomized controlled trial of a mailed intervention. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(4):501–7.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of Mr. Kaveh Dehghan (Data analyst) in assisting us with search strategy and implementation.

Funding

This research was supported by NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR001881.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shahrzad Bazargan-Hejazi - principal investigator; drafting of the manuscript; study concept and design; acquisition of data; technical, or material support; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; and study supervisor. Anaheed Shirazi - acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; and critical revision of the manuscript. Andrew Wang - drafting of the manuscript; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; and critical revision of the manuscript. Nathan A. Shlobin - acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; and critical revision of the manuscript. Krystal Karunungan - acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; and critical revision of the manuscript. Robert Mazio – acquisition and interpretation of data. Joshua Shulman - technical, or material support Gul Ebrahim – critical revision of the manuscript William Shy - critical revision of the manuscript Stuart Slavin - critical revision of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study did not require institutional review board approval or patient consent because no patient data was collected, and only previously published studies were utilized.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bazargan-Hejazi, S., Shirazi, A., Wang, A. et al. Contribution of a positive psychology-based conceptual framework in reducing physician burnout and improving well-being: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ 21, 593 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03021-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03021-y