Abstract

Background

This study aimed to assess the difference in serum levels of leptin and adiponectin in patients with periodontitis and in periodontally healthy individuals and evaluate the changes in circulating leptin and adiponectin after periodontal therapy. Leptin and adiponectin are the most generally studied adipokines that function as inflammatory cytokines. Although the association between periodontitis and serum levels of leptin and adiponectin has been studied extensively, the results were not consistent.

Methods

A systematic search of the Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library up to September 2016 was conducted. The studies were screened and selected by two writers according to the specific eligibility criteria. The quality of included cross-sectional studies was assessed using the quality assessment form recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies. The meta-analyses were conducted using the STATA 12.0 software.

Results

A total of 399 manuscripts were yielded and 25 studies were included in the present meta-analysis. Significantly elevated serum levels of leptin and decreased serum levels of adiponectin in patients with periodontitis were observed in the subgroup analysis of body mass index (BMI) <30. The overall and subgroup analyses showed no significant change in the serum levels of leptin in patients with periodontitis after periodontal treatment. The subgroup analysis of systemically healthy patients showed no significant change in serum levels of adiponectin in patients with periodontitis after periodontal treatment.

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis supported elevated serum levels of leptin and decreased serum levels of adiponectin in patients with periodontitis compared with controls in the BMI <30 population. In systemically healthy patients with periodontitis, serum levels of leptin and adiponectin do not significantly change after periodontal treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Periodontitis is a common progressive inflammatory disease affecting human periodontal support tissues [1]. The development of periodontitis cause a series of clinical manifestations including gingival bleeding, periodontal pocket formation, alveolar bone absorption, and eventually teeth loss [2]. The progression of chronic periodontitis (CP) is mediated by both bacterial invasions and host immunoinflammatory responses [3,4,5]. The immunocytes activated by the exogenous bacteria not only destroy bacteria but also release myriads of products, known as inflammatory cytokines, which exert an anti-bacterial effect and, on the contrary, contribute to the destruction of periodontal tissues [6, 7]. Hence, considerable attention was paid in drawing an association between periodontitis and certain inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8). Moreover, the presence of such inflammatory cytokines has been proved to be altered in serum, gingival crevicular fluid, and saliva in patients with periodontitis [8,9,10,11].

Adipokines are a group of bioactive molecules primarily secreted by adipose tissues [12]. Adipokines, such as leptin, adiponectin, resistin, and visfatin, are important in periodontal inflammation for functioning as proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines [13]. Of all these adipokines, leptin and adiponectin have been extensively described because of their critical role in immune response, bone and lipid metabolism, energy expenditure, and insulin sensitivity modulation [14]. Leptin, a 16-kDa nonglycosylated peptide hormone expressed by the obese gene, has been considered to be the most generally studied adipokine [15, 16]. Besides being known as an appetite controller, leptin exerts roles in both systemic and local inflammatory processes [17,18,19,20]. Leptin is considered to be a proinflammatory cytokine involved in the inflammatory response as it modulates the function of immunocytes such as T-cells, monocytes, and natural killer cells. These immunocytes are directly activated by leptin, leading to an elevation in the release of other inflammatory mediators [19, 21]. Inversely, adiponectin, the insulin-sensitizing adipokine, mediates anti-inflammatory effects in the process of inflammation and functions in cell proliferation, differentiation, and regeneration [13, 22]. Recent studies have reported that adipokines, such as leptin and adiponectin, are produced in periodontal cells and contribute to periodontal infection and healing [23, 24]. Additionally, adipokines are also revealed to play roles in periodontitis-related systemic conditions such as diabetes and obesity [25,26,27]. In this light, to clarify the association between adipokines and periodontitis can be conducive to investigate not only the mechanism of periodontal inflammations but also the impact of periodontitis on systemic diseases.

Although multiple studies have been conducted to find the association between periodontitis and serum levels of leptin and adiponectin, the findings were inconsistent [16, 28,29,30,31,32]. Moreover, no meta-analyses have been reported on this issue so far. Therefore, the present systematic review and meta-analysis were performed to summarize individual study results into a quantitative estimation of the association between periodontitis and serum levels of leptin and adiponectin. An evidence-based result would be valuable in providing a more precise evaluation of the association between adipokines and periodontitis. The clinically focused questions of present study are: (1) Will serum levels of leptin and adiponectin be significantly altered in patients with periodontitis comparing with periodontally healthy individuals? (2) Do serum levels of leptin and adiponectin change significantly after periodontal treatment?

Methods

The review protocol was prospectively registered at the National Institute for Health Research PROSPERO, International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews under registration CRD42016047213. The present study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement [33].

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for the studies comparing the difference in serum levels of leptin and adiponectin between patients with periodontitis and periodontally healthy individuals were as follows: (1) the studies were case-controlled, cross-sectional, prospective, or clinical trials; (2) the periodontitis groups consisted of patients diagnosed with periodontal disease, including chronic periodontitis (CP) and aggressive periodontitis (AP). Present study employed the definition of periodontitis as: at least 1 sites with probing pocket depth (PPD) ≥4 mm [34]; (3) the healthy groups consisted of periodontally healthy individuals; and (4) serum levels of leptin and adiponectin were detected and provided in both the periodontitis and healthy groups.

The inclusion criteria for the studies evaluating the change in circulating leptin and adiponectin after periodontal treatment were as follows: (1) the studies were randomized controlled trials, nonrandomized controlled trials, or prospective; (2) patients with periodontitis were enrolled; (3) periodontal treatments such as scaling and root planning and periodontal surgeries with or without antibiotics administration were applied; and (4) serum levels of leptin and adiponectin of the patients with periodontitis at baseline and after the periodontal treatments were provided.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the studies were review articles, case reports, letters, or conference abstracts; (2) studies with insufficient data for the statistical analyses; and (3) those with repeated data.

Search strategy and record screen

Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library up to September 2016 were systemically searched to identify the pertinent studies. The search strategies are presented in Table 1. In addition, the reference lists of the selected manuscripts and related reviews were also manually searched and screened for a comprehensive search result.

According to the eligibility criteria, titles and abstracts were screened first and the full-text paper screen was conducted next. The results were screened by two authors (Xin Chen and Ling Zhang) independently, and a third author (Yuting He) was consulted if any discrepancy existed.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from the included studies by two authors (Junfei Zhu and Ling Zhang) independently, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion: (1) Name of the first author and year of publication; (2) study design; (3) country and ethnicity; (4) group size; (5) body mass index (BMI); (6) age; (7) outcomes; (8) systemic conditions; (9) smoking status; (10) posttherapy time; and (11) serum levels of leptin and/or adiponectin.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated by two authors (JF Zhu and L Zhang) independently, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The quality of the included cross-sectional studies was assessed using the quality assessment form for cross-sectional studies recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). A total of 11 items were involved in this form, and 1 point could be achieved if the item was reflected in the study. No points could be achieved if the item was not considered or unclear. The final scores ranged from 0 to 11. Studies with scores 0–4, 5–8, and 9–11 were considered as of low, moderate, and high quality, respectively [35, 36]. In addition, for the studies evaluated the changes in serum levels of leptin and adiponectin after periodontal treatment, the included double-arm clinical trials and randomized controlled clinical trials were treated as single-arm clinical trial designs. Therefore, the Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies (MINORS) was applied for assessing the quality of the included clinical trials [37]. A total of 12 items were involved in MINORS, and 0–2 points could be achieved in each of the items. The first eight items were designed for the studies without a control group,and the other four items are the additional criteria for comparative studies. As in present quality assessment we only evaluated the quality of single-arm designs, the first 8 items were employed. The final scores ranged from 0 to 16. Studies with scores 0–5, 6–10, and 11–16 were considered as of low, moderate, and high quality, respectively [38].

Data Analyses

Four models were considered in the present meta-analysis: serum levels of leptin in patients with periodontitis versus healthy individuals (L1), serum levels of adiponectin in patients with periodontitis versus healthy individuals (A1), serum levels of leptin in patients with periodontitis before versus after periodontal treatment (L2), and serum levels of adiponectin in patients with periodontitis before versus after periodontal treatment (A2). The data on serum levels of leptin and adiponectin were presented as mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD). If the outcomes were provided only as median (minimum – maximum) [39,40,41], the results were shifted to the form of M ± SD according to the estimation method reported by Hozo et al. [42]. The standard mean difference (SMD) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) were applied to estimate the association between serum levels of leptin and adiponectin and periodontitis. Heterogeneity was estimated by chi-square and I; a P value <0.05 and I 2 > 50% were considered significant heterogeneity [43], and then the random-effects model was used; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used to assure statistical efficiency. Subgroup analyses were conducted according to the type of periodontitis, BMI, smoking status, systemic conditions, and types of periodontal treatment. The following characteristics were included as covariates in the meta-regression to explore the potential sources of heterogeneity: type of periodontitis, BMI, smoking status, and presence of systemic disease. A characteristic was considered as the source of heterogeneity if P <0.05. Moreover, Galbraith plots were conducted to investigate the heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were performed to test the robustness of the results. Publication bias was measured by Begg’s and Egger’s linear regression tests. A significant publication bias was considered if the P value was <0.05. All statistical analyses were processed using the STATA 12.0 software.

Results

Study selection

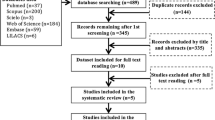

A total of 399 manuscripts were yielded using the search strategy. After deleting the duplicates, full-text screens were conducted and 25 studies were identified to be eligible. The process of study selection and the reasons for exclusion are listed in Fig. 1.

Characteristics and quality assessment

Of the 25 included studies, all 16 studies focusing on the difference in serum levels of leptin and/or adiponectin between patients with periodontitis and healthy individuals employed the cross-sectional design [16, 30,31,32, 40, 41, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. Besides this, nine clinical trials detecting the serum levels of leptin and adiponectin in patients with periodontitis before and after periodontal treatments were included [28, 29, 39, 54,55,56,57,58,59]. The clinical trials performed by Duzagac et al., Purwar et al., and Shimada et al. also enrolled the periodontally healthy groups and provided the pretherapy data on the serum levels of leptin and adiponectin in patients with periodontitis and healthy individuals [54, 57, 58]. The studies performed by Altayet al., Duzagacet al., Goncalveset al, Mendoza-Azpuret al, and Zimmermann et al. provided the data on subjects with BMI <30 and BMI ≥30 separately [31, 32, 39, 54,55,56], and the study performed by Zeigler et al. provided only the data on obesity subjects. The study performed by Ay et al. enrolled both the CP and aggressive periodontitis (AP) groups [40]. The study performed by Gundala et al. enrolled both the systemically healthy group and the acute myocardial infarction (AMI) group [47]. The study performed by Davies et al. provided the data on male and female subjects separately [44]. For the included cross-sectional studies, the AHRQ scores ranged from 5 to 7. The study performed by Gangadhar et al. was the only cross-sectional study considered to be of low quality (4 points) [46]. Other included cross-sectional studies were all considered to be of moderate quality. All of the included clinical trials were considered to be of high quality. The characteristics and quality assessment of the included studies are presented in Table 2.

Overall and subgroup analyses

In the L1 model, higher serum levels of leptin were observed in the overall and subgroup analyses of BMI <30. The subgroup analysis of BMI ≥30 did not show significant results. The overall and subgroup analyses of the L1 model demonstrated significant heterogeneity. In the A1 model, the overall and subgroup analyses showed a significantly decreased serum level of adiponectin in patients with periodontitis, except for the subgroup of BMI ≥30. In the L2 model, the overall and subgroup analyses showed no significant change in serum levels of leptin in patients with periodontitis after periodontal treatment. In the A2 model, the overall and subgroup analyses of BMI <30 showed a significantly elevated level of serum adiponectin in patients with periodontitis after periodontal treatment. However, no significant result was obtained by the subgroup analysis of BMI ≥30 and the subgroup analyses based on the methods of periodontal treatment and systemic conditions. The results of overall and subgroup analyses are summarized in Table 3, and the forest plots of the subgroup analyses of BMI <30 are presented in Fig. 2.

Meta-regression, Galbraith plots, and sensitivity analyses

Because of the presence of heterogeneities in the subgroup of BMI <30 under all of the four models and the inconsistency of the results between the subgroups of BMI <30 and BMI ≥30 under L1, A1, and A2 models, the meta-regression analyses and Galbraith plots were conducted to investigate the heterogeneity in the subgroup analyses of BMI <30. In addition, the sensitivity analyses were performed to test the stability of the results.

Considering the limitation in the number of studies included in L2 and A2 models (n < 10), the meta-regression analyses were performed only in the L1 and A1 models. The results of meta-regression based on the covariates including the type of periodontitis, BMI, systemic conditions, and smoking status failed to find the source of heterogeneity in the subgroup analyses of BMI <30 (P > 0.05).

Further, the Galbraith plots showed that the studies performed by Shi et al., Purwar et al., Mendoza-Azpur et al., Thanakun et al., and Karthikeyan et al. (L1) [30, 31, 49, 51, 52]; Mendoza-Azpur et al. and Sete et al. (A1) [16, 31]; and Purwar et al. (L2) [57] were located outside of the two lines in the Galbraith plots of the subgroups of BMI <30. After removing the outliers, the heterogeneities effectively decreased, and the results were not materially changed in the subgroups of BMI <30 (L1: SMD = 0.796, 95% CI: 0.572–1.020, P = 0.000; I 2 = 40.9, P = 0.095; A1: SMD = −0.251, 95% CI: −0.408 to −0.095, P = 0.002; I 2 = 13.6, P = 0.323; L2: SMD = −0.162, 95% CI: −0.417 to 0.094, P = 0.215; I 2 = 0.0, P = 0.556). Additionally, in the L1 model, removing the outlier also eliminated the overall heterogeneity, and the overall result was not materially changed (SMD = −0.175, 95% CI:−0.383 to 0.033, P = 0.100; I 2 = 0.0, P = 0.671).

The sensitivity analyses were conducted by removing a single study each time and evaluating the influence of each study on the result. The sensitivity analyses proved the robustness of the results of the BMI <30 subgroups under the L1, A1, and L2 models. However, in the A2 model, the sensitivity analysis showed that the study performed by Sun et al. qualitatively changed the pooled SMD [59]. After this study was removed, the results were changed to the insignificant level, and the heterogeneity was eliminated in both overall and BMI <30 analyses (overall: SMD = 0.109, 95% CI: 0.113–0.330, P = 0.336; I 2 = 0.0, P = 0.839; BMI <30: SMD = 0.065, 95% CI:−0.238 to 0.369, P = 0.673; I 2 = 0.0, P = 0.612). The Galbraith plots and sensitivity analyses are presented in Figs. 3 and 4.

Publication bias

The Begg’s and Egger’s linear regression tests demonstrated the presence of a publication bias in the A2 model (P = 0.042) (Table 2).

Discussion

To the extent of our knowledge, present study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis quantitatively explored the association between circulating leptin and adiponectin and periodontitis. Our results provided evidence that circulating leptin is elevated and adiponectin is decreased in subjects with BMI < 30 and periodontitis.

Leptin is the main adipokine that is positively related to obesity [60]. The structures of leptin and leptin receptors are similar to the long-chain helical cytokine family, including IL-6, IL-11, and so on. Therefore, leptin is considered to be a functional proinflammatory cytokine, which contributes to both innate and acquired immune response [61]. Previous studies have reported an increased leptin circulation during inflammation periods, which was modulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and cytokines such as TNF and IL-1 [62, 63]. Sachot et al. first revealed that the LPS-induced increase in circulating leptin does not occur in the IL-1β-deficient mice, indicating leptin might exert an inflammatory effect through an IL-1β-dependent mechanism [64]. The change in serum levels of leptin was suggested to modulate the function of immunocytes as well as periodontal cells. In human monocytes, leptin enhanced the Prevotella intermedia LPS–induced expression of TNF-α and production in a dose-dependent manner [65]. In periodontal ligament cells, leptin induced the downregulation of TGF-β1, vascular endothelial growth factor, and Runt-related transcription factor-2, indicating an impaired regenerative capacity [66]. Leptin stimulation activated mitogen-activated protein kinase, signal transducer and activator of transcription 1/3, and Akt signaling, and enhanced the expression of MMPs in human gingival fibroblasts [67]. Furthermore, as a pleiotropic adipokine, leptin also exerted an effect on bone metabolism and might contribute to the alveolar bone destruction caused by periodontitis [68]. Through the central nervous system, leptin not only induces bone loss via hypothalamic relay [69] but also inhibits osteogenesis through the sympathetic nervous system [70].

In contrast to leptin, adiponectin, a 244-residue protein produced primarily by adipocytes, was suggested to be inversely associated with obesity [71]. Adiponectin plays an anti-inflammatory role in systemic and local inflammations [72]. It functions by binding to its receptors, adiponectin receptors 1 and 2, which have been found in periodontal tissues [13]. Upon binding to its receptors, adiponectin exerts anti-inflammatory effects such as inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines, induction of anti-inflammatory cytokines, and reduction of adhesion molecule expression, and performs antagonistic effect on toll-like receptors and its ligands [73]. In vivo studies have proved that stimulation with adiponectin improves the regenerative and proliferative capacity of periodontal tissues [24, 74, 75]. Moreover, adiponectin is also involved in the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). It delays and suppresses the metabolic derangements such as insulin resistance and T2DM because of its remarkable insulin-sensitizing property [76].

Emerging evidence suggests that obesity influences the secretion of adipokines [77,78,79]. As recommended by the World Health Organization, a BMI ≥30 can be defined as the presence of obesity [31]. In this light, the subgroup analyses were performed based on BMI, which demonstrated a fluctuation in serum levels of leptin and adiponectin in patients with periodontitis having BMI <30 and ≥30. The present study provided evidence that compared with healthy individuals, serum levels of leptin were elevated and those of adiponectin were decreased in patients with periodontitis having BMI <30. Intuitively, this finding was consistent with previous studies, which supported the same tendency of leptin levels during inflammations [80,81,82]. Nevertheless, the distribution of adiponectin in inflammatory diseases remained controversial. Despite the suppression of secretion of adiponectin in adipocytes by inflammation [73], ample evidence indicates that circulating levels of adiponectin are positively associated with various inflammatory pathologies [83,84,85]. However, in the present meta-analysis, serum levels of adiponectin were attenuated in patients with periodontitis having BMI <30. Further studies are required to validate this finding.

The sensitivity analyses proved the robustness of the results of BMI <30 subgroup under L1, L2, and A1 models, except for the A2 model. As the sensitivity analysis presented, the study performed by Sun et al. qualitatively influenced the results in the A2 model. This might be caused by the presence of T2DM and the large group size of the study [59]. Adiponectin is an insulin-sensitizing hormone that decreases in metabolic disorders including T2DM [86, 87]. This study hypothesized that the periodontal treatment on patients with T2DM might have improved both the periodontitis and T2DM conditions, thereby resulting in a significantly elevated serum level of adiponectin [88, 89]. Besides that, in the A2 model, the subgroup analysis of the studies involving systemic healthy subjects showed an insignificant result, with no heterogeneity. Moreover, the studies included in the L2 model all enrolled systemic healthy subjects. In this light, it was concluded that serum levels of leptin and adiponectin did not change after periodontal treatment in systemically healthy patients with periodontitis.

Considering the studies evaluating the association of serum levels of cytokines between experimental and control groups as cross-sectional designs, the present study applied the AHRQ form for assessing the quality of the included studies in L1 and A1 models [90]. However, multiple previous studies concerning this issue employed the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) for the quality assessment [91,92,93]. The NOS is designed for the meta-analyses of case–control studies and cohort studies, therefore, it is not appropriated for cross-sectional studies.

The present study results, however, has some limitations. First, the quantity of included studies was considered small, especially for the studies enrolling subjects with BMI ≥30. Second, several relevant studies could not be included in present meta-analysis owing to lacking of raw data [94,95,96], or improper publication formats (Abstract) [97]. Additionally, all the included studies in L1 and A1 models were cross-sectional, and because of the limited number of comparative studies, we treated all the included studies as single-arm designs in L2 and A2 models. Therefore, the cause–effect relationship between periodontitis and serum levels of leptin and adiponectin was rarely presented, and the effect of periodontal treatment on serum levels of leptin and adiponectin was not perfectly elucidated. Further, the statistical heterogeneity observed in the present meta-analysis might impact the veracity of the conclusion. Especially, under the L1 model, significant heterogeneity could be observed in all the subgroups. Although Galbraith plots were conducted to clarify the heterogeneity, the proportion of the outliers (5 out of 14) was considered to be high. Therefore, these results should be carefully interpreted. Moreover, an evident publication bias was observed under the A2 model, which might have distorted the present results because of the presence of the gray (unpublished) manuscripts. Finally, other limitations such as the ethodological diversity in estimating periodontal disease and cytokine levels, the adjustment of the data in the included studies [39,40,41], the diversity in sample size and the difference in the qualities and methods of the included studies should be noticed when interpreting the results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, within the limitations of this study, the present meta-analysis supported elevated serum levels of leptin and decreased serum levels of adiponectin in patients with periodontitis compared with controls in the BMI <30 population. In systemically healthy patients with periodontitis, serum levels of leptin and adiponectin did not significantly change after periodontal treatment. Our findings suggested that leptin and adiponectin play as the potential biomarkers for periodontitis. To monitor the adipokines profile may allow clinicians to predict the susceptibility to periodontitis. Further studies are required to explore the mechanism and to clarify the cause–effect relationship between circulating adipokines and periodontitis.

Abbreviations

- AHRQ:

-

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- AP:

-

Aggressive periodontitis

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CP:

-

Chronic periodontitis

- Ctr:

-

Control

- IL-1:

-

Interleukin-1

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- M:

-

mean

- MINORS:

-

Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies

- MMP-8:

-

Metalloproteinase-8

- NA:

-

Not available

- NOS:

-

Newcastle–Ottawa scale

- P:

-

Periodontitis

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SMD:

-

Standard mean difference

- SRP:

-

Scaling and root planning

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-α

References

Kawar N, Gajendrareddy PK, Hart TC, Nouneh R, Maniar N, Alrayyes S. Periodontal disease for the primary care physician. Dis Mon. 2011;57(4):174–83.

Nguyen CM, Kim JW, Quan VH, Nguyen BH, Tran SD. Periodontal associations in cardiovascular diseases: The latest evidence and understanding. J Oral Biol craniofac Res. 2015;5(3):203–6.

Gurav AN. Periodontitis and insulin resistance: Casual or causal relationship? Diabetes Metab J. 2012;36(6):404–11.

Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1809–20.

Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. The bacterial etiology of destructive periodontal disease: current concepts. J Periodontol. 1992;63(4 Suppl):322–31.

Cekici A, Kantarci A, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE. Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2014;64(1):57–80.

Malcolm J, Millington O, Millhouse E, Campbell L, Adrados Planell A, Butcher JP, Lawrence C, Ross K, Ramage G, McInnes IB, et al. Mast Cells Contribute to Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced Bone Loss. J Dent Res. 2016;95(6):704–10. doi:10.1177/0022034516634630. Epub 2016 Mar 1.

Kocak E, Saglam M, Kayis SA, Dundar N, Kebapcilar L, GL B, Hakki SS. Nonsurgical periodontal therapy with/without diode laser modulates metabolic control of type 2 diabetics with periodontitis: a randomized clinical trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2016;31(2):343–53.

Ozcan E, Saygun NI, Serdar MA, Bengi VU, Kantarci A. Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy Reduces Saliva Adipokines and Matrix Metalloproteinases Levels in Periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2016;87(8):934–43. doi:10.1902/jop.2016.160046. Epub 2016 Mar 18.

Polepalle T, Moogala S, Boggarapu S, Pesala DS, Palagi FB. Acute Phase Proteins and Their Role in Periodontitis: A Review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(11):Ze01–05.

Sorsa T, Gursoy UK, Nwhator S, Hernandez M, Tervahartiala T, Leppilahti J, Gursoy M, Kononen E, Emingil G, Pussinen PJ, et al. Analysis of matrix metalloproteinases, especially MMP-8, in gingival creviclular fluid, mouthrinse and saliva for monitoring periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2016;70(1):142–63.

Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Obesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):461s–5s.

Deschner J, Eick S, Damanaki A, Nokhbehsaim M. The role of adipokines in periodontal infection and healing. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2014;29(6):258–69.

Krysiak R, Handzlik-Orlik G, Okopien B. The role of adipokines in connective tissue diseases. Eur J Nutr. 2012;51(5):513–28.

Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395(6704):763–70.

Sete MR, Lira Junior R, Fischer RG, Figueredo CM. Serum adipokine levels and their relationship with fatty acids in patients with chronic periodontitis. Braz Dent J. 2015;26(2):169–74.

Tian YF, Chang WC, Loh CH, Hsieh PS. Leptin-mediated inflammatory signaling crucially links visceral fat inflammation to obesity-associated beta-cell dysfunction. Life Sci. 2014;116(1):51–8.

Koenig S, Luheshi GN, Wenz T, Gerstberger R, Roth J, Rummel C. Leptin is involved in age-dependent changes in response to systemic inflammation in the rat. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;36:128–38.

Tsai SY, Chung KH, Huang SH, Chen PH, Lee HC, Kuo CJ. Persistent inflammation and its relationship to leptin and insulin in phases of bipolar disorder from acute depression to full remission. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(8):800–8.

Arnalich F, Lopez J, Codoceo R, Jim Nez M, Madero R, Montiel C. Relationship of plasma leptin to plasma cytokines and human survivalin sepsis and septic shock. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(3):908–11.

Procaccini C, Jirillo E, Matarese G. Leptin as an immunomodulator. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33(1):35–45.

Carbone F, La Rocca C, Matarese G. Immunological functions of leptin and adiponectin. Biochimie. 2012;94(10):2082–8.

Li W, Huang B, Liu K, Hou J, Meng H. Upregulated Leptin in Periodontitis Promotes Inflammatory Cytokine Expression in Periodontal Ligament Cells. J Periodontol. 2015;86(7):917–26.

Nokhbehsaim M, Keser S, Nogueira AV. Beneficial effects of adiponectin on periodontal ligament cells under normal and regenerative conditions. J Diabetes Res. 2014;2014:796565. doi:10.1155/2014/796565. Epub 2014 Jul 13.

Hayashino Y, Jackson JL, Hirata T, Fukumori N, Nakamura F, Fukuhara S, Tsujii S, Ishii H. Effects of exercise on C-reactive protein, inflammatory cytokine and adipokine in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Metab Clin Exp. 2014;63(3):431–40.

Rodriguez AJ, Nunes Vdos S, Mastronardi CA, Neeman T, Paz-Filho GJ. Association between circulating adipocytokine concentrations and microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled cross-sectional studies. J Diabetes Complications. 2016;30(2):357–67.

Yu Z, Han S, Cao X, Zhu C, Wang X, Guo X. Genetic polymorphisms in adipokine genes and the risk of obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity. 2012;20(2):396–406.

Behle JH, Sedaghatfar MH, Demmer RT, Wolf DL, Celenti R, Kebschull M, Belusko PB, Herrera-Abreu M, Lalla E, Papapanou PN. Heterogeneity of systemic inflammatory responses to periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36(4):287–94.

Bharti P, Katagiri S, Nitta H, Nagasawa T, Kobayashi H, Takeuchi Y, Izumiyama H, Uchimura I, Inoue S, Izumi Y. Periodontal treatment with topical antibiotics improves glycemic control in association with elevated serum adiponectin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2013;7(2):e129–38.

Karthikeyan BV, Pradeep AR. Leptin levels in gingival crevicular fluid in periodontal health and disease. J Periodontal Res. 2007;42(4):300–4.

Mendoza-Azpur G, Castro C, Pena L, Guerrero M-E, De La Rosa M, Mendes C, Chambrone L. Adiponectin, leptin and TNF-alpha serum levels in obese and normal weight Peruvian adults with and without chronic periodontitis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2015;7(3):e380–386.

Zimmermann GS, Bastos MF, Goncxalves TED, Chambrone L, Duarte PM. Local and circulating levels of adipocytokines in obese and normal weight individuals with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2013;84(5):624–33.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535.

Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Northwest Dent. 2000;79(6):31–5.

Bi H, Gan Y, Yang C, Chen Y, Tong X, Lu Z. Breakfast skipping and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(16):3013–9.

Rostom A, Dubé C, Cranney A, et al. Celiac Disease. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2004. (Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 104.) Appendix D. Quality Assessment Forms. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK35156/.

Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(9):712–6.

Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, Zhang C, Li S, Sun F, Niu Y, Du L. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8(1):2–10.

Altay U, Gurgan CA, Agbaht K. Changes in inflammatory and metabolic parameters after periodontal treatment in patients with and without obesity. J Periodontol. 2013;84(1):13–23.

Ay ZY, Kirzioglu FY, Tonguc MO, Sutcu R, Kapucuoglu N. The gingiva contains leptin and leptin receptor in health and disease. Odontology. 2012;100(2):222–31.

Ay ZY, Sutcu R, Kocak H, Kirzioglu FY. Serum leptin levels and their proportional relationship with pro- and antiinflammatory mediators in aggressive periodontitis: preliminary report. Turkish J Med Sci. 2013;43(5):825–30.

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5(1):13.

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available from http://handbook.cochrane.org.

Davies RC, Jaedicke KM, Barksby HE, Jitprasertwong P, Al-Shahwani RM, Taylor JJ, Preshaw PM. Do patients with aggressive periodontitis have evidence of diabetes? A pilot study. J Periodontal Res. 2011;46(6):663–72.

Furugen R, Hayashida H, Yamaguchi N, Yoshihara A, Ogawa H, Miyazaki H, Saito T. The relationship between periodontal condition and serum levels of resistin and adiponectin in elderly Japanese. J Periodontal Res. 2008;43(5):556–62.

Gangadhar V, Ramesh A, Thomas B. Correlation between leptin and the health of the gingiva: a predictor of medical risk. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22(4):537–41.

Gundala R, Chava VK, Ramalingam K. Association of leptin in periodontitis and acute myocardial infarction. J Periodontol. 2014;85(7):917–24.

Nagano Y, Arishiro K, Uene M, Miyake T, Kambara M, Notohara Y, Shiraishi M, Ueda M, Domae N. A low ratio of high molecular weight adiponectin to total adiponectin associates with periodontal status in middle-aged men. Biomarkers. 2011;16(2):106–11.

Purwar P, Khan MA, Mahdi AA, Pandey S, Singh B, Dixit J, Sareen S. Salivary and serum leptin concentrations in patients with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2015;86(4):588–94.

Saito T, Yamaguchi N, Shimazaki Y, Hayashida H, Yonemoto K, Doi Y, Kiyohara Y, Iida M, Yamashita Y. Serum levels of resistin and adiponectin in women with periodontitis: the Hisayama study. J Dent Res. 2008;87(4):319–22.

Shi D, Liu YY, Li W, Zhang X, Sun XJ, Xu L, Zhang L, Chen ZB, Meng HX. Association between plasma leptin level and systemic inflammatory markers in patients with aggressive periodontitis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128(4):528–32.

Thanakun S, Watanabe H, Thaweboon S, Izumi Y. Association of untreated metabolic syndrome with moderate to severe periodontitis in Thai population. J Periodontol. 2014;85(11):1502–14.

Zeigler CC, Wondimu B, Marcus C, Modeer T. Pathological periodontal pockets are associated with raised diastolic blood pressure in obese adolescents. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:41.

Duzagac E, Cifcibasi E, Erdem MG, Karabey V, Kasali K, Badur S, Cintan S. Is obesity associated with healing after non-surgical periodontal therapy? A local vs. systemic evaluation. J Periodont Res. 2016;51(5):604–12. doi:10.1111/jre.12340. Epub 2015 Dec 15.

Goncalves TE, Feres M, Zimmermann GS, Faveri M, Figueiredo LC, Braga PG, Duarte PM. Effects of scaling and root planing on clinical response and serum levels of adipocytokines in patients with obesity and chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2015;86(1):53–61.

Goncalves TE, Zimmermann GS, Figueiredo LC, Souza Mde C, da Cruz DF, Bastos MF, da Silva HD, Duarte PM. Local and serum levels of adipokines in patients with obesity after periodontal therapy: one-year follow-up. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(5):431–9.

Purwar P, Khan MA, Gupta A, Mahdi AA, Pandey S, Singh B, Dixit J, Rai P. The effects of periodontal therapy on serum and salivary leptin levels in chronic periodontitis patients with normal body mass index. Acta Odontol Scand. 2015;73(8):633–41.

Shimada Y, Komatsu Y, Ikezawa-Suzuki I, Tai H, Sugita N, Yoshie H. The effect of periodontal treatment on serum leptin, interleukin-6, and C-reactive protein. J Periodontol. 2010;81(8):1118–23.

Sun WL, Chen LL, Zhang SZ, Wu YM, Ren YZ, Qin GM. Infammatory cytokines, adiponectin, insulin resistance and metabolic control after periodontal intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic periodontitis. Intern Med. 2011;50(15):1569–74.

Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, Kriauciunas A, Stephens TW, Nyce MR, Ohannesian JP, Marco CC, McKee LJ, Bauer TL, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(5):292–5.

Faggioni R, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Leptin regulation of the immune response and the immunodeficiency of malnutrition. FASEB J. 2001;15(14):2565–71.

Grunfeld C, Zhao C, Fuller J, Pollack A, Moser A, Friedman J, Feingold KR. Endotoxin and cytokines induce expression of leptin, the ob gene product, in hamsters. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(9):2152–7.

Kaplan JM, Nowell M, Lahni P, O’Connor MP, Hake PW, Zingarelli B. Short-term high fat feeding increases organ injury and mortality after polymicrobial sepsis. Obesity. 2012;20(10):1995–2002.

Sachot C, Poole S, Luheshi GN. Circulating leptin mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced anorexia and fever in rats. J Physiol. 2004;561(Pt 1):263–72.

Kim SJ. Leptin potentiates Prevotella intermedia lipopolysaccharide-induced production of TNF-alpha in monocyte-derived macrophages. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2010;40(3):119–24.

Nokhbehsaim M, Keser S, Nogueira AV. Beneficial effects of adiponectin on periodontal ligament cells under normal and regenerative conditions. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014:796565.

Williams RC, Skelton AJ, Todryk SM, Rowan AD, Preshaw PM, Taylor JJ. Leptin and Pro-Inflammatory Stimuli Synergistically Upregulate MMP-1 and MMP-3 Secretion in Human Gingival Fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148024.

Upadhyay J, Farr OM, Mantzoros CS. The role of leptin in regulating bone metabolism. Metabolism Clin Exp. 2015;64(1):105–13.

Ducy P, Amling M, Takeda S, Priemel M, Schilling AF, Beil FT, Shen J, Vinson C, Rueger JM, Karsenty G. Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: a central control of bone mass. Cell. 2000;100(2):197–207.

Takeda S, Elefteriou F, Levasseur R, Liu X, Zhao L, Parker KL, Armstrong D, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Leptin regulates bone formation via the sympathetic nervous system. Cell. 2002;111(3):305–17.

Weyer C, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Hotta K, Matsuzawa Y, Pratley RE, Tataranni PA. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(5):1930–5.

Villarreal-Molina MT, Antuna-Puente B. Adiponectin: anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective effects. Biochimie. 2012;94(10):2143–9.

Fantuzzi G. Adiponectin in inflammatory and immune-mediated diseases. Cytokine. 2013;64(1):1–10.

Iwayama T, Yanagita M, Mori K, Sawada K, Ozasa M, Kubota M, Miki K, Kojima Y, Takedachi M, Kitamura M, et al. Adiponectin regulates functions of gingival fibroblasts and periodontal ligament cells. J Periodontal Res. 2012;47(5):563–71.

Zhang K, Zhang X, Yu LY, Xu BY. The effect of adiponectin on human periodontal ligament fibroblasts in vitro. Shanghai J Stomatol. 2012;21(1):48–52.

Chakraborti CK. Role of adiponectin and some other factors linking type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(15):1296–308.

Fowler AJ, Richer AL, Bremner RM, Inge LJ. A high-fat diet is associated with altered adipokine production and a more aggressive esophageal adenocarcinoma phenotype in vivo. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149(4):1185–91.

Lee CH, Woo YC, Wang Y, Yeung CY, Xu A, Lam KS. Obesity, adipokines and cancer: an update. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015;83(2):147–56.

Nakamura K, Fuster JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines: a link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. J Cardiol. 2014;63(4):250–9.

Gualillo O, Eiras S, Lago F, Dieguez C, Casanueva FF. Elevated serum leptin concentrations induced by experimental acute inflammation. Life Sci. 2000;67(20):2433–41.

Karpavicius A, Dambrauskas Z, Sileikis A, Vitkus D, Strupas K. Value of adipokines in predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis: comprehensive review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(45):6620–7.

Lee YH, Bae SC. Circulating leptin level in rheumatoid arthritis and its correlation with disease activity: a meta-analysis. Z Rheumatol. 2016;75(10):1021–7.

Bobbert P, Scheibenbogen C, Jenke A, Kania G, Wilk S, Krohn S, Stehr J, Kuehl U, Rauch U, Eriksson U, et al. Adiponectin expression in patients with inflammatory cardiomyopathy indicates favourable outcome and inflammation control. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(9):1134–47.

Chiang CH, Lai JS, Hung SH, Lee LT, Sheu JC, Huang KC. Serum adiponectin levels are associated with hepatitis B viral load in overweight to obese hepatitis B virus carriers. Obesity. 2013;21(2):291–6.

Krommidas G, Kostikas K, Papatheodorou G, Koutsokera A, Gourgoulianis KI, Roussos C, Koulouris NG, Loukides S. Plasma leptin and adiponectin in COPD exacerbations: associations with inflammatory biomarkers. Respir Med. 2010;104(1):40–6.

Lindberg S, Jensen JS, Bjerre M, Pedersen SH, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Galatius S, Jeppesen J, Mogelvang R. Adiponectin, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22(3):276–83.

Vinitha R, Ram J, Snehalatha C, Nanditha A, Shetty AS, Arun R, Godsland IF, Johnston DG, Ramachandran A. Adiponectin, leptin, interleukin-6 and HbA1c in the prediction of incident type 2 diabetes: A nested case–control study in Asian Indian men with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;109(2):340–6.

Botero JE, Rodriguez C, Agudelo-Suarez AA. Periodontal treatment and glycaemic control in patients with diabetes and periodontitis: an umbrella review. Aust Dent J. 2016;61(2):134–48.

Li Q, Hao S, Fang J, Xie J, Kong XH, Yang JX. Effect of non-surgical periodontal treatment on glycemic control of patients with diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Trials. 2015;16:291.

Setia MS. Methodology Series Module 3: Cross-sectional Studies. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61(3):261–4.

Li HM, Zhang TP, Leng RX, Li XP, Li XM, Pan HF. Plasma/Serum Leptin Levels in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Meta-analysis. Arch Med Res. 2015;46(7):551–6.

Mei YJ, Wang P, Chen LJ, Li ZJ. Plasma/Serum Leptin Levels in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arch Med Res. 2016;47(2):111–7.

Stubbs B, Wang AK, Vancampfort D, Miller BJ. Are leptin levels increased among people with schizophrenia versus controls? A systematic review and comparative meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;63:144–54.

Iwamoto Y, Nishimura F, Soga Y, Takeuchi K, Kurihara M, Takashiba S, Murayama Y. Antimicrobial periodontal treatment decreases serum C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, but not adiponectin levels in patients with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2003;74(8):1231–6.

Kardesler L, Buduneli N, Cetinkalp S, Kinane DF. Adipokines and Inflammatory Mediators After Initial Periodontal Treatment in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2010;81(1):24–33.

Matsumoto S, Ogawa H, Soda S, Hirayama S, Amarasena N, Aizawa Y, Miyazaki H. Effect of antimicrobial periodontal treatment and maintenance on serum adiponectin in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36(2):142–8.

Abou-Raya A, Abou-Raya S, AbuElKheir H. Periodontal disease, systemic inflammation and adipocytokines: Effect of periodontal therapy on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:76.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was financially funded by Shenzhen Airlines (MHRDZ201101).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JFZ and BG conceived the study. XQG and LZ conducted the electronic search. XC, LZ and YTH screened the results. JFZ and LZ performed the data extraction. SHZ and BLL contributed to the statistical analyses. JFZ drafted the manuscript. HYY and XQG contributed to the revision of the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, J., Guo, B., Gan, X. et al. Association of circulating leptin and adiponectin with periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 17, 104 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-017-0395-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-017-0395-0