Abstract

Background

The number of revision total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) in Asian countries is projected to increase with the rapid growth of primary TKA. We investigated the factors associated with the incidence of revision TKA using a nationally representative database.

Methods

Data collected by the Health Insurance Review Agency of Korea, from 260,068 TKA patients between 2007 and 2012, were used to estimate the incidence rate and cumulative incidence of revision TKA according to age, gender, and hospital TKA and prosthesis manufacturer volume. Age, hospital, and manufacturer volume were categorized into three groups. The incidence rates and cumulative incidences of revision TKA were computed by combining age and gender, and by combining hospital and prosthesis manufacturer volume.

Results

Incidence rates per 100,000 person-years were as follows: 1) by age: < 65 years, 447.2; 65–74 years, 363.7; ≥ 75 years, 270.9, 2) by gender: male, 537.8; female, 346.1; 3) by hospital volume (procedures/year): < 20, 536.9; 20–199, 432.3; ≥ 200, 300.1; and 4) by manufacturer volume (prostheses/year): < 1500, 772.3; 1500–3999, 453.9; ≥ 4000, 345.6. The revision TKA incidence rate in young males was significantly higher compared to that in elderly females. The difference in cumulative incidence, between hospitals with an annual volume of < 20 procedures and those with a volume of 20–199 procedures, was reduced for manufacturers with an annual volume of ≥ 4000. Similarly, the difference in cumulative incidence between manufacturers with an annual volume of <1500 prostheses and those with a volume of 1500–3999 prostheses was reduced in hospitals with an annual volume of ≥ 200.

Conclusion

Revision TKA incidence varied according to age, gender, and hospital and manufacturer volume. This data could inform clinical decisions and healthcare strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an efficacious and cost-effective pain-relieving procedure that improves mobility and quality of life in patients with severe knee arthritis [1–3]. TKA use has increased in numerous countries, particularly in Asia, commensurate with an aging population and continued socioeconomic development [4–7]. Changes to contemporary TKA prosthesis design and surgical techniques (including a greater number of arthroplasty-specific hospitals), together with patient indications and medical circumstances, impact upon the decision to apply TKA. In a recent study, the increased rate of TKA use in Korea was markedly higher compared to developed countries [5]; revision TKA is also projected to increase commensurate with this increase in primary TKA [8, 9].

Revision TKA represents a major challenge for healthcare providers and patients, and is associated with a substantial economic burden likely to affect national medical and insurance policies [10–12]. Many studies have reported on the epidemiology of, and factors associated with, revision TKA [4, 8–10, 13–15], primarily in the context of large single-center, or multi-center, settings [4, 13, 15]. Therefore, smaller hospitals, which account for a substantial proportion of the total number of TKA procedures performed, may be underrepresented such that drawing definitive conclusions regarding national revision TKA incidence is problematic [16–18]. Several studies conducted in Norway, Australia and Sweden have addressed this issue by using national (or in the US, statewide [Medicare]) arthroplasty databases [9, 19–22].

However, to date only one Asian study has used national databases to evaluate revision TKA use [23]. Given the increasing popularity of TKA in Asia, which accounts for > 60 % of the world’s population, and the different characteristics and medical circumstances of Asian vs. Western patients, revision TKA use in this continent warrants further study [4–7].

Several reports indicate an association between TKA outcomes and the number of procedures performed at hospitals (hospital volume) [9, 17, 19, 21, 24, 25]. However, only two Asian studies have assessed the impact of hospital stay duration, cost of hospitalization and postoperative infection status, and not specifically in the context of revision TKA [6, 26]. Furthermore, to our knowledge there has been no previous investigation of the potential relationship between the frequency with which particular manufacturers’ prostheses are used (prosthesis manufacturer volume) and revision TKA incidence.

Therefore, we investigated revision TKA incidence according to age group, gender, and hospital and prosthesis manufacturer volume, using a nationally representative Health Insurance Review Agency (HIRA) database containing reimbursement records between 2007 and 2012.

Methods

This study used a retrospective cohort design using national data collected between 2007 and 2012 by the Health Insurance Review Agency (HIRA) of Korea, a non-profit organization supported by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare. All Koreans are obligated to contribute to the National Health Insurance Service, and pay hospitals or clinics 20–30 % of the total cost for medical procedures excluding cosmetic surgery or novel, unproven treatments. The remaining 70–80 % of costs are recouped by hospitals and clinics upon submission of claims to the HIRA detailing the health care services provided (including diagnoses, procedures, hospitalization period, and medical costs incurred). The HIRA reviews each claim, following which the National Health Insurance Corporation issues expenses according to the decision of the HIRA. Approximately 97 % of the Korean population is enrolled in this system; the remaining 3 % are under the Medical Aid Program, which is also supervised by the HIRA such that all information concerning medical practices can ultimately be obtained from the HIRA database. The HIRA database can be regarded as a complete enumeration; the subjects of this study were essentially all of the patients undergoing primary or revision TKA in Korea during the study period. Therefore, unlike typical studies using sampling databases, we did not need to make statistical assumptions for the study population. Similarly, other studies using the HIRA database did not perform statistical calculations for assumptions [23, 27, 28].

We identified all primary total knee replacement arthroplasties performed in Korea (denoted by HIRA codes N0712 and N2072) between January 1st, 2007 and December 31st, 2012. Patients between 45 and 90 years of age at the time of their primary TKA were included, with those also undergoing revision TKA identified by the codes N1712 and N3712, regardless of the reasons for surgery. If revision TKA codes preceded primary TKA codes, the data were excluded. A material code for the femoral component (E200-) was used to identify the prosthesis manufacturer in each case.

Data from a total of 260,068 patients who underwent primary TKA during the study period were analyzed. Their mean age was 68.8 ± 6.9 years, and there were 30,388 (11.7 %) males and 229,680 (88.3 %) females.

We calculated the incidence rate (per 100,000 primary TKA patient-years) and cumulative incidence (per 100,000 primary TKA patients) of revision TKA, with the period between primary and revision TKA representing the failure time. The incidence rates and cumulative incidences of revision TKA were computed according to age group, gender, and hospital and prosthesis manufacturer volume. The cumulative incidence of revision TKA was computed by combining age and gender and by combining hospital and prosthesis manufacturer volume. There were three age groups (<65, 65–74, and ≥ 75 years), in line with a previous study that analyzed the risk factors for TKA failure [13]. When deciding the cut-off values and numbers of groups for hospital volumes or prosthesis manufacturer volumes, we attempted to determine the number of groups and cut-off values that would allow optimal subject numbers in each group and the most noticeable difference in the revision rate among the groups based on hospital volumes or prosthesis manufacturer volumes. Based on the results, hospital volume was categorized into three groups: < 20, 20–199, and ≥ 200 primary procedures/year. These cut-offs were similar to those used in a study that evaluated the cost-effectiveness of TKA according to hospital volume [29]. Similarly, prosthesis manufacturer volume was also categorized into three groups: < 1500, 1500–3999 and ≥ 4000 prostheses/year.

Results

During the study, 2,669 (1 %) patients received revision surgery, the cumulative incidence of which increased linearly over time (Fig. 1). Of these patients, 1,612 (60.4 %) underwent revision surgery at the same hospital at which their primary TKA was performed; in 1,257 (47.1 %) patients, the prosthesis used during their primary and revision surgeries were from the same manufacturer. In 1,045 revision surgeries, both the hospital and prosthesis manufacturer were identical to those of the primary surgery (39.2 %).

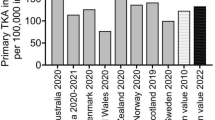

The overall incidence rate of revision TKA was 367.3/100,000 person-years; the incidence was higher in the youngest age group and males (Table 1). In the detailed analysis subdivided by age groups, the incidence in patients fifty years old or younger was extremely high (Fig. 2). When comparing the groups defined by age and gender, the youngest male group had the highest incidence rate of revision TKA (Fig. 3).

Lower hospital and prosthesis manufacturer volumes were associated with higher revision TKA incidence rates (Table 2) and cumulative incidences (Figs. 4 and 5). However, during comparison of groups defined according to hospital and prosthesis manufacturer volume, the cumulative incidence of revision TKA, of lower- (<20 procedures/year) and intermediate-volume hospitals (20–199 procedures/year) was similar when prosthesis manufacturer volume was high (≥4000 prostheses/year; Fig. 6). Similarly, the difference in cumulative incidence of revision TKA, between higher- (≥4000 prostheses/year) and intermediate- (1500–3999 prostheses/year) prosthesis manufacturer volumes, was lower in the context of higher-volume hospitals (≥200 procedures/year; Fig. 7).

Discussion

This study evaluated information pertaining to revision TKA operations performed in Korea between 2007 and 2012, using a near-complete HIRA dataset. In particular, we assessed for the first time the association between prosthesis manufacturer volume and revision TKA incidence.

Few studies conducted in other Asian countries have dealt with the epidemiology of revision TKA. A study from Taiwan using national data reported that the number of revision TKAs increased by 23 % from 1998 to 2009 [23]. In that study, old age and male gender were associated with increases in the revision TKA rates, which concurred with our results. The proportion of females among those undergoing revision TKA was 72.2 % in the Taiwan study and 81 % in the Japan study [4], both of which were lower than our result of 88.3 %.

Higher revision rate was observed in younger patients, which accords with the results of studies of Western populations [2, 9, 15, 18, 30]. McCalden et al. [30] reported higher rates of aseptic loosening, instability, wear and/or osteolysis in younger patients, probably due to their greater levels of physical activity. Furthermore, younger patients are more likely to present with complex preoperative conditions, such as previous failed surgeries or posttraumatic deformities, which could lead to increased revision rates [30]. Surgeons may also be less likely to recommend revision TKA for elderly patients [2].

Our results also accord with those from Western countries demonstrating higher rates of revision TKA in males compared to females [2, 9, 15, 18, 31–35]; for example, Singh et al. [35] reported significantly higher rates of revision TKA, at 5 years post-primary TKA in males. Higher rates of polyethylene wear and osteolysis in male patients may be due to gender differences in knee biomechanics of and/or physical activity levels, thereby leading to higher rates of revision TKA [31, 33]. Higher infection rates in male TKA patients may also be a contributory factor [33]. Revision TKA was particularly common in younger males, such that the decision to apply TKA should be receive particularly careful consideration in this population.

Our data accord with previous studies in which lower hospital volume was associated with higher rates of revision TKA [9, 18, 19, 21, 36]. The mechanism underlying this relationship remains unknown. Kreder et al. [36] suggested that the difference in revision rates observed between lower- and higher-volume hospitals, at 1-year post-primary TKA, may be attributable to differences in expertise among healthcare providers rather than to differences in the prosthesis equipment itself. Hospital facilities and equipment, the experience of the surgeon, and the use of a selective referral system (i.e., sending patients to hospitals associated with good TKA outcomes) may all represent important factors.

Our analysis of the relationship between incidence rates and prosthesis manufacturer volume, which has not been assessed in previous studies, was similar to that observed for hospital volume. A surgeon's experience with a particular manufacturer’s prosthesis, and its design and quality, may influence revision TKA incidence. In our study, the cumulative incidences of revision TKA in intermediate- (20–199 procedures/year) and higher-volume hospitals (≥200 procedures/year) (Fig. 4) were similar to those when the prosthesis manufacturer volume exceeded 4000 prostheses/year (Fig. 6). However, we observed a decrease in the cumulative incidence of revision TKA in lower-volume hospitals (<20 procedures/year) for manufacturers with an annual volume of ≥ 4000 (Figs. 4 and 6). Combined with our other results, our findings suggest that the use of primary TKA prostheses with a higher prosthesis manufacturer volume (≥4000 prostheses/year) would reduce the revision rate, and its effect seems to be more helpful in lower-volume hospitals.

This study had several limitations. First, in cases of infection, patients managed by debridement or replacement of the polyethylene insert were not included in the study; only patients who underwent revision knee arthroplasty were included. Therefore, the TKA revision rates reported herein are not representative of the overall TKA failure rate. Second, we assessed incidence according to hospital and prosthesis manufacturer volume only, and evaluated neither the experience of surgeons nor the frequency with which a particular model of prosthesis was used. Third, the particular characteristics of Korean TKA patients (e.g., high proportion of females, small proportion of procedures performed by lower-volume hospitals [<20 procedures/year], and different living arrangements) may limit the generalizability of our data [16, 17, 37]. Fourth, although the same manufacturer produces different components, we did not distinguish the component type from a material code, but identified each manufacturer.

Conclusions

Total knee arthroplasty performed in young, male patients, at lower-volume hospitals and with lower prosthesis manufacturer volumes, were associated with a higher incidence of revision TKA. In addition to age and gender, revision TKA incidence also varied according to hospital and prosthesis manufacturer volume. These data could inform clinical decisions and healthcare strategies; further studies are required to evaluate the association between revision TKA incidence and prosthesis manufacturer volume in other ethnic populations.

Abbreviations

- HIRA:

-

health insurance review agency

- TKA:

-

total knee arthroplasty

References

Callahan CM, Drake BG, Heck DA, Dittus RS. Patient outcomes following tricompartmental total knee replacement. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1994;271(17):1349–57.

Heck DA, Robinson RL, Partridge CM, Lubitz RM, Freund DA. Patient outcomes after knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;356:93–110.

Lavernia CJ, Guzman JF, Gachupin-Garcia A. Cost effectiveness and quality of life in knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;345:134–9.

Kasahara Y, Majima T, Kimura S, Nishiike O, Uchida J. What are the causes of revision total knee arthroplasty in Japan? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(5):1533–8. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-2820-2.

Koh IJ, Kim TK, Chang CB, Cho HJ, In Y. Trends in use of total knee arthroplasty in Korea from 2001 to 2010. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(5):1441–50. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2622-y.

Wei MH, Lin YL, Shi HY, Chiu HC. Effects of provider patient volume and comorbidity on clinical and economic outcomes for total knee arthroplasty: a population-based study. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(6):906–12. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2009.06.033. e1.

Yan CH, Chiu KY, Ng FY. Total knee arthroplasty for primary knee osteoarthritis: changing pattern over the past 10 years. Hong Kong Med J. 2011;17(1):20–5.

Bansal A, Khatib ON, Zuckerman JD. Revision total joint arthroplasty: the epidemiology of 63,140 cases in New York State. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(1):23–7. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.04.006.

Dy CJ, Marx RG, Bozic KJ, Pan TJ, Padgett DE, Lyman S. Risk factors for revision within 10 years of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(4):1198–207. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3416-6.

Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Chiu V, Vail TP, et al. The epidemiology of revision total knee arthroplasty in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):45–51. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0945-0.

Burns AW, Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, MacDonald SJ, Rorabeck CH. Cost effectiveness of revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:29–33. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000214420.14088.76.

Kim S. Changes in surgical loads and economic burden of hip and knee replacements in the US: 1997–2004. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(4):481–8. doi:10.1002/art.23525.

Koh IJ, Cho WS, Choi NY, Kim TK, Kleos Korea Research G. Causes, risk factors, and trends in failures after TKA in Korea over the past 5 years: a multicenter study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(1):316–26. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3252-8.

Pabinger C, Berghold A, Boehler N, Labek G. Revision rates after knee replacement. Cumulative results from worldwide clinical studies versus joint registers. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(2):263–8. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2012.11.014.

Rand JA, Trousdale RT, Ilstrup DM, Harmsen WS. Factors affecting the durability of primary total knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(2):259–65.

Hervey SL, Purves HR, Guller U, Toth AP, Vail TP, Pietrobon R. Provider Volume of Total Knee Arthroplasties and Patient Outcomes in the HCUP-Nationwide Inpatient Sample. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(9):1775–83.

Katz JN, Barrett J, Mahomed NN, Baron JA, Wright RJ, Losina E. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and the outcomes of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(9):1909–16.

Paterson JM, Williams JI, Kreder HJ, Mahomed NN, Gunraj N, Wang X, et al. Provider volumes and early outcomes of primary total joint replacement in Ontario. Can J Surg. 2010;53(3):175–83.

Badawy M, Espehaug B, Indrekvam K, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI, Furnes O. Influence of hospital volume on revision rate after total knee arthroplasty with cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(18):e131. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00943.

Clements WJ, Miller L, Whitehouse SL, Graves SE, Ryan P, Crawford RW. Early outcomes of patella resurfacing in total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2010;81(1):108–13. doi:10.3109/17453670903413145.

Manley M, Ong K, Lau E, Kurtz SM. Total knee arthroplasty survivorship in the United States Medicare population: effect of hospital and surgeon procedure volume. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(7):1061–7. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2008.06.011.

Robertsson O, W-Dahl A. The Risk of Revision After TKA Is Affected by Previous HTO or UKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(1):90–3. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3712-9.

Kim HA, Koh SH, Lee B, Kim IJ, Seo YI, Song YW, et al. Low rate of total hip replacement as reflected by a low prevalence of hip osteoarthritis in South Korea. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(12):1572–5. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2008.04.024.

Singh JA, Kwoh CK, Boudreau RM, Lee GC, Ibrahim SA. Hospital volume and surgical outcomes after elective hip/knee arthroplasty: a risk-adjusted analysis of a large regional database. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(8):2531–9. doi:10.1002/art.30390.

Soohoo NF, Zingmond DS, Lieberman JR, Ko CY. Primary total knee arthroplasty in California 1991 to 2001: does hospital volume affect outcomes? J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(2):199–205. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2005.03.027.

Mitsuyasu S, Hagihara A, Horiguchi H, Nobutomo K. Relationship between total arthroplasty case volume and patient outcome in an acute care payment system in Japan. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(5):656–63. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2005.09.007.

Lim S, Koo BK, Lee EJ, Park JH, Kim MH, Shin KH, et al. Incidence of hip fractures in Korea. J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26(4):400–5. doi:10.1007/s00774-007-0835-z.

Yoon HK, Park C, Jang S, Jang S, Lee YK, Ha YC. Incidence and mortality following hip fracture in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26(8):1087–92. doi:10.3346/jkms.2011.26.8.1087.

Losina E, Walensky RP, Kessler CL, Emrani PS, Reichmann WM, Wright EA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: patient risk and hospital volume. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1113–21. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.136. discussion 21–2.

McCalden RW, Robert CE, Howard JL, Naudie DD, McAuley JP, MacDonald SJ. Comparison of outcomes and survivorship between patients of different age groups following TKA. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 Suppl):83–6. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.03.034.

Dalury DF, Mason JB, Murphy JA, Adams MJ. Analysis of the outcome in male and female patients using a unisex total knee replacement system. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2009;91(3):357–60. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.91B3.21771.

Khatod M, Inacio M, Paxton EW, Bini SA, Namba RS, Burchette RJ, et al. Knee replacement: epidemiology, outcomes, and trends in Southern California: 17,080 replacements from 1995 through 2004. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(6):812–9. doi:10.1080/17453670810016902.

MacDonald SJ, Charron KD, Bourne RB, Naudie DD, McCalden RW, Rorabeck CH. The John Insall Award: gender-specific total knee replacement: prospectively collected clinical outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(11):2612–6. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0430-1.

O'Connor MI. Implant survival, knee function, and pain relief after TKA: are there differences between men and women? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1846–51. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1782-5.

Singh JA, Kwoh CK, Richardson D, Chen W, Ibrahim SA. Gender and surgical outcomes and mortality after primary total knee arthroplasty: a risk-adjusted analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(7):1095–102. doi:10.1002/acr.21953.

Kreder HJ, Grosso P, Williams JI, Jaglal S, Axcell T, Wal EK, et al. Provider volume and other predictors of outcome after total knee arthroplasty: a population study in Ontario. Can J Surg. 2003;46(1):15–22.

Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991–2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227–36. doi:10.1001/2012.jama.11153.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CHS drafted the manuscript. CBC drafted the manuscript and interpreted the data. SHC participated in the study design and collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. JHJ revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. SBK conceived the study, and participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Chang Ho Shin and Chong Bum Chang contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shin, C.H., Chang, C.B., Cho, SH. et al. Factors associated with the incidence of revision total knee arthroplasty in Korea between 2007 and 2012: an analysis of the National Claim Registry. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 16, 320 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0781-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0781-1