Abstract

Background

A concept referred to as locomotive syndrome (LS) was proposed by the Japanese Orthopaedic Association in order to help identify middle-aged and older adults who may be at high risk of requiring healthcare services because of problems associated with locomotion. Cardiometabolic disorders, including obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, have a high prevalence worldwide. The purpose of this study was to determine the associations between LS and both body composition and cardiometabolic disorders.

Methods

The study participants were 165 healthy adult Japanese women volunteers living in rural areas. LS was defined as a score ≥16 on the 25-question Geriatric Locomotive Function Scale (GLFS-25). Height, body weight, body fat percentage, body mass index (BMI), and bone status were measured. Bone status was evaluated by quantitative ultrasound (i.e., the speed of sound [SOS] of the calcaneus) and was expressed as the percent of Young Adult Mean of the SOS (%YAM). Comorbid conditions of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes were assessed using self-report questionnaires.

Results

Twenty-nine participants (17.6 %) were classed as having LS. The LS group was older, shorter, and had a higher body fat percentage, a higher BMI, and lower bone status than the non-LS group. Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that participants with a BMI ≥23.5 kg/m2 had a significantly higher risk for LS than those with a BMI <23.5 kg/m2 (odds ratio [OR] = 3.78, p < 0.01). Furthermore, GLFS-25 scores were higher in participants with than those without hypertension, diabetes, or obesity, and significantly increased with the number of present disorders.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that BMI may be a useful screening tool for LS. Furthermore, because hypertension and diabetes were associated with LS, the prevention of these disorders accompanied by weight management may help protect against LS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Japan is rapidly transforming into a super-aged society. The Japanese Statistics Bureau reported that as of 2015, individuals aged 65 years or older comprised 26.2 % of the Japanese population [1]. Parallel with this transformation is an increase in the incidence of health issues such as stroke, senility, dementia, falls, fractures, and joint disorders, and in turn, the number of individuals requiring nursing care [2].

Maintaining a healthy locomotive system, which includes the bone, cartilage, muscle, and nervous systems, is the foundation of increased disability-free life expectancy. It follows that, from a public health perspective, preventing the deterioration of motor function is an issue that requires urgent attention. Therefore, an epidemiological concept referred to as locomotive syndrome (LS) [2, 3] has been proposed by the Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA). LS primarily affects elderly individuals who currently require nursing care services owing to problems involving the locomotive system or those who have risk conditions that will likely necessitate such services in the future [4]. LS is caused by the reduced muscle strength and balance associated with aging and locomotive pathologies including osteoporosis, osteoarthritis (OA), and sarcopenia [2]. In females, LS may also be caused by the decreasing levels of physical activity and bone mineral density (BMD) that tend to occur after menopause. The incidence of LS increases with age, and is significantly higher in women (35.6 %) than in men (21.2 %) [5, 6]. As beneficial locomotive exercises for the prevention of LS, the JOA recommends performing “half-squats” and “unipedal standing balance exercises with open eyes” [3].

The 25-question Geriatric Locomotive Function Scale (GLFS-25), a quantitative and evidence-based screening tool, can be used to identify individuals with LS [7, 8]. A previous study reported finding a Spearman’s correlation coefficient of 0.85 (p < 0.001) for the association between GLFS-25 scores and the European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions Index (EQ-5D), indicating that the GLFS-25 had excellent concurrent validity [7].

Identifying factors associated with the development of LS is crucial for its prevention. Results from a number of recent studies suggest that GLFS-25 scores strongly correlate with several physical performance measures, including the unipedal standing balance and Timed Up And Go tests [5, 9–13]. However, only a few reports [5, 14] have focused on the association between the development of LS and body composition, even though numerous studies have reported that weight, body fat percentage, and BMD are associated with cardiovascular disease, various cancers, osteoporosis, hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidemia [15–21].

An association was recently reported between abdominal obesity and LS in elderly Japanese women, suggesting that waist circumference may be useful measure to assess the risk for LS [22].

Metabolic syndrome comprises a combination of medical disorders, including increased fasting plasma glucose, abdominal obesity, high triglyceride levels, and high blood pressure, that increase the risk of developing metabolic conditions and cardiovascular disease [23]. In conjunction with metabolic syndrome, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, which are known as the “deadly quartet,” have a high prevalence worldwide [24]. Many studies have reported that physical activity and body components are associated with metabolic syndrome [17–21]. The proportion of the Japanese population with LS (47 million) is estimated to be more than twice that with metabolic syndrome (20 million) [25, 26].

In the present study, we evaluated body composition using body mass index (BMI), body fat percentage, and bone status, and hypothesized that these variables would be predictive of GLFS-25 scores. Confirmation of this hypothesis would indicate that, in addition to sports performance training, control of body composition could be used to prevent LS. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the association between body composition and LS, the threshold values of body composition measures for discriminating between individuals with and without LS, and the OR of LS according to body composition above or below these thresholds in elderly Japanese women living in rural areas. An additional objective was to determine the association between LS and cardiometabolic disorders.

Methods

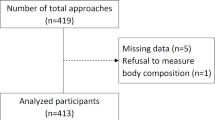

Participants

This study was conducted in a rural area (Tanabe city, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan) between January 2013 and March 2015. The study inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Japanese women, age > 60 years; 2) ability to walk independently; and 3) living at home and being capable of self-care. All participants initially underwent body composition measurements, in the order of height, weight, and body fat percentage, followed by an evaluation of LS status at a public hall where a “Lecture meeting and checkup for health” was held with support from the local government. Afterwards, 198 women were asked to complete a self-report questionnaire at home regarding comorbid conditions and then to return the questionnaire by mail. A stamped envelope was provided to encourage the return of the questionnaire. A total of 165 women underwent the measurements and returned the questionnaire (mean age ± standard deviation, 68.8 ± 6.1 years; range, 60–83 years).

Measurement of variables

Body weight and body fat percentage were measured using the KaradaScan Body Composition Monitor with Scale (HBF-362; Omron Co., Kyoto, Japan) while participants were wearing normal indoor clothing. The procedure was performed with the participants standing barefoot on a metal surface in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. BMI was calculated as weight divided by the square of height, and obesity was defined as BMI ≥25 kg/m2 in accordance with the guidelines of the Japan Society for the Study of Obesity [27]. Bone status was assessed using speed of sound (SOS) measured using a quantitative ultrasound (QUS) device (Canon Life Care Solutions Inc., CM-200, Osaka, Japan) at the calcaneus of the dominant foot while the participants were barefoot and seated. QUS, which has a number of advantages, including portability, low cost, and a lack of exposure to radiation [28], enables the evaluation of bone quality, especially the microarchitecture at the calcaneus, and is useful for predicting risk for future fracture [29]. Bone status was shown as the percent of Young Adult Mean of the SOS (%YAM) [30]. It has been reported that calcaneal QUS parameters reflect the characteristics of the trochanteric area of the proximal hip, although these values are not specifically reflective of values of the femoral neck or shaft [31].

Evaluation of LS

LS status (presence and degree) was evaluated based on GLFS-25 scores (Additional file 1). The GLFS-25 is a self-report questionnaire composed of the following 25 items focusing on the month before completing the measure: four questions on pain; 16 on activities of daily living; three on social function; and two on mental health status [7]. These 25 items are scored from 0 (no impairment) to 4 (severe impairment), with a total score range from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate worse locomotive function. The cutoff score for LS, as determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, is 16 points [7].

Comorbid conditions

Comorbid conditions of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes were assessed using the following question on the self-report questionnaire: “Do you presently take medication for hypertension, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia?”

Statistical analysis

Participants were classified as LS (≥16) or non-LS (<16) based on GLFS-25 scores, and then independent variables were compared between groups. For numerical variables, normality of distribution and homogeneity of variance were tested before across-group comparisons. When the assumptions of normal distribution and homogeneity of variance were met in both groups, we performed the student t-test, and when the assumption of normal distribution was met, but not the assumption of homogeneity of variance, we performed Welch’s t-test. When the data were non-normally distributed, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used.

ROC analysis was used to evaluate the threshold of each body composition measure (BMI, body fat percentage, and %YAM) in order to discriminate the LS from the non-LS group. An area under the ROC (AUC-ROC) curve of 1.00 was taken to indicate perfect discrimination, whereas an AUC-ROC of 0.50 was taken to indicate the complete absence of discrimination.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the age-adjusted significance of the prevalence of LS. The chi-square test was used for comparison of prevalence or number of cardiometabolic disorders between non-LS and LS. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for comparison of GLFS-25 scores classified by with and without cardiometabolic disorders, as well as by the number of present disorders. Statistical analysis was conducted using JMP 11 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All statistical tests were 2-tailed, and a significance level of 0.05 was used.

Results

Age, height, body weight, body fat percentage, BMI, bone status, GLFS-25 score, and the prevalence of components of cardiometabolic disorder are shown in Table 1. Twenty-nine participants (17.5 %) had a GLFS-25 score ≥16 and were thereby classified as LS (Table 2). The LS group was older and shorter than the non-LS group, and had a higher body fat percentage, a higher BMI, and lower bone status (Table 2).

ROC analysis was conducted for each body composition measure, and the threshold for discriminating the non-LS and LS groups was identified. This threshold was 37.3 % for body fat percentage, 23.5 kg/m2 for BMI, and 73 % for %YAM (Table 3). ORs for the prevalence of LS according to the threshold values are shown in Table 4. High BMI was a significant risk factor for LS, with an OR of 3.78 as determined by multiple logistic regression analysis.

Figure 1 shows GLFS-25 scores classified by the presence or absence of each metabolic syndrome component (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and obesity). GLFS-25 scores were higher in participants with than without hypertension or diabetes, and in obese than in non-obese participants. Figure 2 shows GLFS-25 scores classified by the number of present cardiometabolic disorders. The results showed that GLFS-25 scores significantly increased with the number of cardiometabolic disorders (p < 0.01). Table 5 shows a comparison of the prevalence or number of cardiometabolic disorders between non-LS and LS subjects. The prevalence of LS was higher in participants with than without hypertension (p < 0.05) and obesity (p < 0.01).

GLFS-25 scores in participants with and without hypertension (a), diabetes (b), hyperlipidemia (c), and obesity (d). HT, hypertension; NHT, non-hypertension; DM, diabetes mellitus; NDM, non-diabetes mellitus; HL, hyperlipidemia; NHL, non-hyperlipidemia; OB, obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2); NOB, non-obesity (BMI <25 kg/m2); *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; error bars, standard deviation

Discussion

Association between body composition and LS

LS was proposed by the JOA in 2007 in order to identify individuals at high risk of requiring nursing care owing to problems associated with the locomotive system [2]. The GLFS-25 was subsequently developed to measure the presence and degree of LS in Japanese individuals [7]. However, since its implementation, the GLFS-25 cutoff value for identifying individuals with LS has been determined in accordance with health-related quality of life [7, 11]; therefore, information on the association between GLFS-25 scores and body composition is limited. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to determine the association between LS as defined by GLFS-25 scores and body composition measures in elderly Japanese women.

Our results showed that participants with LS were shorter, had a higher body fat percentage, a higher BMI, and lower bone status than participants without LS. Previous studies have reported similar results in middle-aged and elderly Japanese women [5, 14]. Muramoto et al. found that GLFS-25 scores had a significant positive correlation with body fat percentage and BMI, a negative correlation with body height and BMD, and no correlation with body weight according to correlation analysis [5].

Based on comparative analysis, participants with LS have been shown to have significantly greater BMI and body fat percentage and lower height than those without LS, whereas no significant difference has been observed in body weight or BMD [14].

In the present study, we found that participants with LS were shorter than those without LS. Shorter height has been reported to be significantly associated with fear of falling in elderly Japanese individuals [32]. Shorter height may be caused by an age-related change in the curvature of the spine or atrophy of trunk extension muscles, which can decrease postural control. A reduction in postural control can cause fear of falling or a decline in the amount of physical activity [33]. Therefore, we propose that the LS group included more participants that had lost height due to a change in the curvature of the spine or atrophy of trunk extension muscles than the non-LS group, and therefore had less postural control and engaged in fewer activities in daily life, which increased their risk for developing LS.

The present results showed that participants with LS had a higher body fat percentage than those without LS. Increased body fat causes more mechanical stress in weight-bearing joints and promotes the degeneration of joint tissue through the production and release of adipokines [34]. Adipokines are derived from adipocytes and may upregulate receptor activators of nuclear kappa B ligand, leading to increased bone resorption and reduced BMD [35]. Participants with a higher body fat percentage may have secreted more adipocytes, and this may have had a negative influence on the movement of the joints, thereby increasing the risk of LS.

The present study showed that a BMI ≥23.5 k/m2 was significantly associated with LS, with an OR of 3.78 as identified by multiple logistic regression analysis. The Japan Society for the Study of Obesity defines the cutoff for obesity as a BMI 25 kg/m2 [8]. In the present study, the mean BMI of the participants with LS was ≥25 kg/m2. Furthermore, GLFS-25 scores were higher in obese than in non-obese participants (Fig. 2d). LS is closely associated with age-related skeletal disorders such as osteoporosis, OA, lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS), degenerative spinal disease and sarcopenia [4]. Furthermore, obesity is a risk factor for these disorders because mechanical overload on weight-bearing joints can activate chondrocytes, accelerate the degeneration of cartilage, and increase static compressive loading and pressures associated with postures that damage disc integrity [36–38]. Moreover, it has been proposed that metabolic factors, including inflamed adipose tissue, dyslipidemia, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction and leptin dysregulation, as well as the clustering of these factors in metabolic syndrome, may play a crucial role in obesity-induced OA [39–41]. These findings support the present results regarding the association between obesity and LS.

Association between LS and cardiometabolic disorders

Obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia are known as the “deadly quartet” [24]. Numerous studies have reported that BMD is associated with these disorders [17–21]. The second purpose of the present study was to determine the association between LS and cardiometabolic disorders. Our results showed that LS is associated with hypertension, diabetes, and overweight, as well as with higher BMI. Furthermore, GLFS-25 scores significantly increased with the number of present cardiometabolic disorders.

There are some reports on the association between cardiometabolic disorders and OA. Some evidence suggests that metabolic factors such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and elevated glucose concentration are associated with the development and progression of OA [40, 42]. In particular, the advanced glycation end products in cartilage collagen seem to be associated with both the senescent cartilage matrix and reduced chondrocyte function [43]. The presence of advanced glycation end products associated with the expression of advanced glycation end-product receptors in the cartilage collagen results in the increased production of matrix metalloproteinase and the modulation of the chondrocyte phenotype to hypertrophy and OA [44, 45].

OA and hypertension have been shown to frequently coexist [46]. The proposed mechanism of the development of OA with hypertension is as follows: narrow and/or constricted vessels restrict blood flow to subchondral bone, impairing circulation and nutritional supply to overlying articular cartilage, which ultimately contributes to the deterioration of cartilage in OA [47].

Mutual relations exist between the occurrence and presence of musculoskeletal diseases, particularly knee OA and cardiometabolic disorders [48]. Yoshimura et al. suggested that metabolic risk factors such as overweight, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and impaired glucose tolerance increase the risk of occurrence and progression of knee OA [49, 50]. Recent reports have indicated that waist circumference, back muscle strength, and spinal inclination angle are important risk factors for LS [22]. In the present study, we demonstrated that LS is associated with hypertension and obesity, as well as a higher BMI. Furthermore, GLFS-25 scores significantly increased with the number of present cardiometabolic disorders. These findings suggest a close relationship between the locomotive system and cardiometabolic organs.

The proportion of adults with BMI >25 kg/m2 has significantly increased worldwide [51]. The present findings contribute to the identification of factors that may prevent locomotive disorder and metabolic syndrome, particular in Western societies, in which many patients have metabolic syndrome. Although the concept of LS is currently used only in Japan, we believe it will become more common worldwide as the population continues to age.

The results of the present study suggest that BMI might be a useful measure for the simple detection of LS. Furthermore, hypertension and diabetes were found to be associated with LS. Weight management and prevention of these disorders may help protect against LS in elderly women. Elderly men should be included in future studies.

Limitations and future research

This study did have several limitations. First, the sample size of 165 was small; this number only represents about 1.2 % of all women aged between 60 and 83 years in Tanabe city. Furthermore, no significant relationship was found between LS and dyslipidemia; this may have been due in part to a lack of statistical power. Second, because the participants in this study were all Japanese women, care should be taken in generalizing the results to men or other ethnic groups. Third, data from a cross-sectional study are not sufficient to determine whether a causal relationship exists between BMI, LS, and cardiometabolic disorders. LS may cause obesity or hypertension and diabetes because it limits physical activity. Conversely, these cardiometabolic disorders may lead to the development of LS. It is therefore crucial to perform longitudinal studies to clarify the causal relationships among these factors. Fourth, comorbid conditions were only assessed using self-report questionnaires; therefore, blood pressure, blood glucose concentration, and blood lipid concentration measurements were not controlled. Thus, untreated participants with comorbid conditions may have been excluded from analysis; however, this possibility is low because participants attending the “Lecture meeting” would have been expected to have relatively high health awareness. Fifth, further research in larger-sized studies should measure lean mass because it is an important component of BMI. It is possible that BMI underestimates body fat percentage in clinical populations [52].

Conclusion

BMI, body fat percentage, and bone status were significantly associated with LS. In particular, a BMI ≥23.5 k/m2 was significantly associated with LS. Moreover, GLFS-25 scores were higher in participants with a BMI ≥25 kg/m2, hypertension, and diabetes than in the respective comparison groups. These results suggest that BMI is an important measure for the detection of LS. Furthermore, weight management and the prevention of metabolic syndrome may reduce the risk for LS.

Abbreviations

- %YAM:

-

Percent of Young Adult Mean of the SOS

- AUC:

-

area under the curve

- BMD:

-

Bone mineral density

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- GLFS-25:

-

25-question Geriatric Locomotive Function Scale

- JOA:

-

Japanese Orthopaedic Association

- LS:

-

Locomotive syndrome

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- QUS:

-

qualitative ultrasound

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SOS:

-

speed of sound

References

Statistics Bureau. Population estimates (March 2015). http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/ListE.do?lid=000001131732. Accessed 22 Sept 2016.

Nakamura K. A “super-aged” society and the “locomotive syndrome”. J Orthop Sci. 2008;3(1):1–2. doi:10.1007/s00776-007-1202-6.

Japanese Orthopaedic Association. Guidebook on locomotive syndrome. Tokyo: Bunkodo; 2010 (in Japanese).

Nakamura K. The concept and treatment of locomotive syndrome: its acceptance and spread in Japan. J Orthop Sci. 2011;16(5):489–91. doi:10.1007/s00776-007-1202-6.

Muramoto A, Imagama S, Ito Z, Hirano K, Ishiguro N, Hasegawa Y. Physical performance tests are useful for evaluating and monitoring the severity of locomotive syndrome. J Orthop Sci. 2012;17(6):782–8. doi:10.1007/s00776-013-0382-5.

Sasaki E, Ishibashi Y, Tsuda E, Ono A, Yamamoto Y, Inoue R, et al. Evaluation of locomotive disability using loco-check: a cross-sectional study in the Japanese general population. J Orthop Sci. 2013;17(6):782–8. doi:10.1007/s00776-012-0329-2.

Seichi A, Hoshino Y, Doi T, Akai M, Tobimatsu Y, Iwaya T. Development of a screening tool for risk of locomotive syndrome in the elderly: the 25-question Geriatric Locomotive Function Scale. J Orthop Sci. 2012;17(6):782–8. doi:10.1007/s00776-011-0193-5.

Japanese Orthopaedic Association 2013. Locomotive syndrome pamphlet. P.08. https://locomo-joa.jp/en/index.pdf. Accessed 22 Sept 2016.

Yoshimura N, Oka H, Muraki S, Akune T, Hirabayashi N, Matsuda S, et al. Reference values for hand grip strength, muscle mass, walking time, and one-leg standing time as indices for locomotive syndrome and associated disability: the second survey of the ROAD study. J Orthop Sci. 2011;16(6):768–77. doi:10.1007/s00776-011-0160-1.

Hirano K, Hasegawa Y, Imagama S, Wakao N, Muramoto A, Ishiguro N. Impact of spinal imbalance and back muscle strength on locomotive syndrome in community-living elderly people. J Orthop Sci. 2012;17(5):532–7. doi:10.1007/s00776-012-0266-0.

Seichi A, Hoshino Y, Doi T, Akai M, Tobimatsu Y, Kita K, et al. Determination of the optimal cutoff time to use when screening elderly people for locomotive syndrome using the one-leg standing test (with eyes open). J Orthop Sci. 2014;19(4):620–6. doi:10.1007/s00776-014-0581-8.

Fukumori N, Yamamoto Y, Takegami M, Yamazaki S, Onishi Y, Sekiguchi M, et al. Association between hand-grip strength and depressive symptoms: locomotive syndrome and health outcomes in Aizu cohort study (LOHAS). Age Ageing. 2015;44(4):592–8. doi:10.1093/ageing/afv013.

Nakamura M, Hashizume H, Oka H, Okada M, Takakura R, Hisari A, et al. Physical performance measures associated with locomotive syndrome in middle-aged and older Japanese women. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2015;38(4):202–7. doi:10.1519/JPT.0000000000000033.

Muramoto A, Imagama S, Ito Z, Hirano K, Tauchi R, Ishiguro N, et al. Threshold values of physical performance tests for locomotive syndrome. J Orthop Sci. 2013;18(4):618–26. doi:10.1007/s00776-013-0382-5.

Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-88.

Bang E, Tanabe K, Yokoyama N, Chijiki S, Kuno S. Relationship between thigh intermuscular adipose tissue accumulation and number of metabolic syndrome risk factors in middle-aged and older Japanese adults. Exp Gerontol. 2016;16(79):26–30. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2016.03.010.

Hwang DK, Choi HJ. The relationship between low bone mass and metabolic syndrome in Korean women. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:425–31. doi:10.1007/s00198-009-0990-2.

Kim HY, Choe JW, Kim HK, Bae SJ, Kim BJ, Lee SH, et al. Negative association between metabolic syndrome and bone mineral density in Koreans, especially in men. Calcif Tissue Int. 2010;86(5):350–8. doi:10.1007/s00223-010-9347-2.

Xue P, Gao P, Li Y. The association between metabolic syndrome and bone mineral density: a meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2012;42(3):546–54. doi:10.1007/s12020-012-9684-1.

Muka T, Trajanoska K, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Oei L, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, et al. The association between metabolic syndrome, bone mineral density, hip bone geometry and fracture risk: the Rotterdam study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129116. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129116.

Ebron K, Andersen CJ, Aguilar D, Blesso CN, Barona J, Dugan CE, et al. A larger body mass index is associated with increased atherogenic dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and low-grade inflammation in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2015;13(10):458–64. doi:10.1089/met.2015.0053.

Muramoto A, Imagama S, Ito Z, Hirano K, Tauchi R, Ishiguro N, et al. Waist circumference is associated with locomotive syndrome in elderly females. J Orthop Sci. 2014;19(4):612–9. doi:10.1007/s00776-013-0382-5.

Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome--a new world-wide definition. A consensus statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23:469–80.

Kaplan NM. The deadly quartet. Upper-body obesity, glucose intolerance, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1514–20.

Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Oka H, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, lumbar spondylosis, and osteoporosis in Japanese men and women: the research on osteoarthritis/osteoporosis against disability study. J Bone Miner Metab. 2009;27:620–8.

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Measures for national health Promotion, Ref-70. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/wp-hw2/part2/p3_0024.pdf. Accessed 22 Sept 2016.

Examination Committee of Criteria for ‘Obesity Disease’ in Japan; Japan Society for the Study of Obesity. New criteria for ‘obesity disease’ in Japan. Circ J. 2002;66:987–92.

Kohri T, Kaba N, Murakami T, Narukawa T, Yamamoto S, Sakai T, Sasaki S. Search for promotion factors of ultrasound bone measurement in Japanese males and pre/post-menarcheal females aged 8–14 years. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2012;58(4):263–71. 10.3177/jnsv.58.263.

Chin KY, Ima-Nirwana S. Calcaneal quantitative ultrasound as a determinant of bone health status: what properties of bone does it reflect? J Med Sci. 2013;10(12):1778–83. doi:10.7150/ijms.6765.

Iizuka Y, Iizuka H, Mieda T, Tajika T, Yamamoto A, Takagishi K. Population-based study of the association of osteoporosis and chronic musculoskeletal pain and locomotive syndrome: the Katashina study. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(6):1085–9. doi:10.1007/s00776-015-0774-9.

Zhang L, Lv H, Zheng H, Li M, Yin P, Peng Y, Gao Y, Zhang L, Tang P. Correlation between parameters of calcaneal quantitative ultrasound and hip structural analysis in osteoporotic fracture patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0145879. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0145879.

Nishimura A, Ikezoe T, Kitase S, et al. The factor influences fear of falling in elderly people. Phys Ther Kyoto. 2006;35:98–9 (in Japanese).

Ogaya S, Ikezoe T, Tateuchi H, et al. The relationship of fear of falling and daily activity to postural control in the elderly. Phys Ther Sci. 2010;37:78–84 (in Japanese).

Conde J, Scotece M, López V, Gómez R, Lago F, Pino J, et al. Adipokines: novel players in rheumatic diseases. Discov Med. 2013;15:73–83.

Hofbauer LC, Schoppet M. Clinical implications of the osteoprotegerin/ RANKL/RANK system for bone and vascular diseases. JAMA. 2004;292:490–5.

Halade GV, El Jamali A, Williams PJ, Fajardo RJ, Fernandes G. Obesity-mediated inflammatory microenvironment stimulates osteoclastogenesis and bone loss in mice. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46(1):43–52. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2010.09.014.

Knutsson B, Sandén B, Sjödén G, Järvholm B, Michaëlsson K. Body mass index and risk for clinical lumbar spinal stenosis: a cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(18):1451–6. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000001038.

Ou CY, Lee TC, Lee TH, Huang YH. Impact of body mass index on adjacent segment disease after lumbar fusion for degenerative spine disease. Neurosurgery. 2015;76(4):396–401. doi:10.1227/NEU.0000000000000627.

Flamme CH. Obesity and low back pain--biology, biomechanics and epidemiology. Orthopade. 2005;34(7):652–7.

Musumeci G, Aiello FC, Szychlinska MA, Di Rosa M, Castrogiovanni P, Mobasheri A. Osteoarthritis in the XXIst century: risk factors and behaviours that influence disease onset and progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(3):6093–112. doi:10.3390/ijms16036093.

Thijssen E, van Caam A, van der Kraan PM. Obesity and osteoarthritis, more than just wear and tear: Pivotal roles for inflamed adipose tissue and dyslipidaemia in obesity-induced osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;54(4):588–600. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keu464.

Zhuo Q, Yang W, Chen J, Wang Y. Metabolic syndrome meets osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:729–37. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2012.135.

Verzijl N, DeGroot J, Ben ZC, Brau-Benjamin O, Maroudas A, Bank RA. Crosslinking by advanced glycation end products increases the stiffness of the collagen network in human articular cartilage: a possible mechanism through which age is a risk factor for osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:114–23.

Yammani RR, Carlson CS, Bresnick AR, Loeser RF. Increase in production of matrix metalloproteinase 13 by human articular chondrocytes due to stimulation with S100A4: role of the receptor for advanced glycation end products. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2901–11.

Cecil DL, Johnson K, Rediske J, Lotz M, Schmidt AM, Terkeltaub R. Inflammation-induced chondrocyte hypertrophy is driven by receptor for advanced glycation end products. J Immunol. 2005;175:8296–302.

Singh G, Miller JD, Lee FH, Pettitt D, Russell MW. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among US adults with self-reported osteoarthritis: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8(15 Suppl):S383–91.

van den Berg WB. Osteoarthritis year 2010. In review: pathomechanisms. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(4):338–41. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2011.01.022.

Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Oka H, Tanaka S, Kawaguchi H, Nakamura K, et al. Mutual associations among musculoskeletal diseases and metabolic syndrome components: a 3-year follow-up of the ROAD study. Mod Rheumatol. 2015;25(3):438–48. doi:10.3109/14397595.2014.972607.

Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Oka H, Tanaka S, Kawaguchi H, Nakamura K, et al. Accumulation of metabolic risk factors such as overweight, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and impaired glucose tolerance raises the risk of occurrence and progression of knee osteoarthritis: a 3-year follow-up of the ROAD study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(11):1217–26. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2012.06.006.

Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Oka H, Tanaka S, Ogata T, Kawaguchi H, et al. Association of knee osteoarthritis with the accumulation of metabolic risk factors such as overweight, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and impaired glucose tolerance in Japanese men and women: the ROAD study. J Rheumatol. 2011;16(6):768–77. doi:10.1007/s00776-015-0741-5.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9945):766–81. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8.

Shah NR, Braverman ER. Measuring adiposity in patients: the utility of body mass index (BMI), percent body fat, and leptin. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e33308. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033308.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Hiroshi Kameda, Mr. Shota Okumi, Mr. Nobuhiro Koike, Mr. Daiki Kanata, Mr. Sho Tachibana, Mr. Shodai Tanaka, Ms. Sakiko Enomoto, Mr. Takuma Nishimae, Mr. Kenta Higashi, Mr. Yusuke Saeki, Mr. Ryosuke Hashikaku, Mr. Taichi Takemoto, and Mr. Yoshiki Kushi at Osaka Kawasaki Rehabilitation University for their cooperation.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

MN participated in the study design, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript; YK provided assistance in the statistical analysis; RK, SN, AM, and HU performed measurements of variables; HH, HO, and MY provided assistance in the literature review and revised the manuscript; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All subjects provided written informed consent to use their data in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Wakayama Medical University (Reference No. 1005). This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

The 25-question Geriatric Locomotive Function Scale [7]. (DOCX 154 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakamura, M., Kobashi, Y., Hashizume, H. et al. Locomotive syndrome is associated with body composition and cardiometabolic disorders in elderly Japanese women. BMC Geriatr 16, 166 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0339-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0339-6