Abstract

Background

Overweight and obese persons are at risk of a number of medical conditions which can lead to further morbidity and mortality. The primary objective of this study is to provide an estimate of the incidence of each co-morbidity related to obesity and overweight using a meta-analysis.

Methods

A literature search for the twenty co-morbidities identified in a preliminary search was conducted in Medline and Embase (Jan 2007). Studies meeting the inclusion criteria (prospective cohort studies of sufficient size reporting risk estimate based on the incidence of disease) were extracted. Study-specific unadjusted relative risks (RRs) on the log scale comparing overweight with normal and obese with normal were weighted by the inverse of their corresponding variances to obtain a pooled RR with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

A total of 89 relevant studies were identified. The review found evidence for 18 co-morbidities which met the inclusion criteria. The meta-analysis determined statistically significant associations for overweight with the incidence of type II diabetes, all cancers except esophageal (female), pancreatic and prostate cancer, all cardiovascular diseases (except congestive heart failure), asthma, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis and chronic back pain. We noted the strongest association between overweight defined by body mass index (BMI) and the incidence of type II diabetes in females (RR = 3.92 (95% CI: 3.10–4.97)). Statistically significant associations with obesity were found with the incidence of type II diabetes, all cancers except esophageal and prostate cancer, all cardiovascular diseases, asthma, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis and chronic back pain. Obesity defined by BMI was also most strongly associated with the incidence of type II diabetes in females (12.41 (9.03–17.06)).

Conclusion

Both overweight and obesity are associated with the incidence of multiple co-morbidities including type II diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Maintenance of a healthy weight could be important in the prevention of the large disease burden in the future. Further studies are needed to explore the biological mechanisms that link overweight and obesity with these co-morbidities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A substantial literature has emerged which has found that overweight and obesity are major causes of co-morbidities which can lead to further morbidity and mortality [1–3]. The related health care costs are substantial [4–6]. As the number of associated co-morbidities continues to increase, systematic reviews and meta-analysis are important tools to summarize the findings and produce more precise estimates of risk associated with overweight and obesity.

The primary objective of this study is to provide a comprehensive review of the incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight. We have identified a number of recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses on type II diabetes [7], cardiovascular diseases [8, 9], cancer [10], breast cancer [11, 12], esophageal or cardia adenocarcinoma [13], pancreatic cancer [14] and prostate cancer [15]. The rationale for re-conducting a review is threefold. Firstly, it has been reported that abdominal obesity, defined by waist circumference (WC) measurement in comparison to the more traditional obesity definition, based on Body Mass Index (BMI) measurement, is an even better predictor of many cardiovascular diseases and type II diabetes [16–24]. However, most recent reviews have only focused on obesity defined by BMI instead of WC. For example, a recent meta-analysis study has compared BMI and WC as risk factors for ischaemic heart disease and stroke but it only included studies with population from the Asia Pacific region [8]. Also, only meta-analysis studies on BMI and type II diabetes have been conducted [7].

Secondly, associating the incidence of co-morbidities with overweight and obesity can be done in many ways since there are many different definitions. For instance, many previous reviews have combined studies that have found the association with per unit change of BMI (kg/m2) and WC (cm) measurements [7–9, 11, 14, 15]. We are interested in measuring the incidence by categorization of overweight and obesity defined by BMI and WC measurements, which has not been the focus of a majority of previous reviews.

Thirdly, the previous meta-analysis studies primarily focused on individual co-morbidities and they were conducted by different authors and using different search strategies, inclusion criteria and analysis methods. Only one recent meta-analysis study conducted by Katzmarzyk and Janssen comprehensively estimated the incidence of eight different chronic diseases associated with obesity [5]. An objective of this review is to apply a consistent methodology across all relevant co-morbidities. This enables us to compare the number of studies and size of effect across all co-morbidities.

Methods

Exposure variables

The definition for overweight is having a BMI greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2 and below 30 kg/m2. The definition for obesity is having a BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2 [25, 26]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the definition for abdominally overweight or obesity is a WC of greater than or equal to 80 cm and 88 cm, respectively, for females, and 94 cm and 102 cm, respectively, for males [25, 26].

Disease outcomes

Possible co-morbidities of overweight and obesity were identified from a preliminary search reviewed by an eating disorder and obesity expert and a review of previous systematic reviews [1–3]. We also reviewed the leading causes of global burden of disease and included the diseases reported with burden attributable to overweight and obesity [27]. Twenty co-morbidities were initially included in this analysis: cancer (kidney, colorectal, prostate, ovarian, uterine/endometrial, esophageal, pancreatic, and post-menopausal breast), type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease risk (hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism, stroke, dislipidaemia), gallbladder disease, chronic back pain, osteoarthritis, asthma, and sleep apnea.

Literature review

A literature search was conducted using the search terms: 'Incidence, Prevalence, Risk, Risk Factors, Cohort Studies, Longitudinal Studies, Follow-up Studies, or Prospective Studies' in combination with 'Adipose Tissue, Obesity, Body Mass Index, or Body Composition' (all "exploded"). These same search terms were applied to each co-morbidity (also "exploded") for both Medline and Embase search engines to retrieve all potentially relevant English articles (until January, 2007). We also searched ISI Web of Science, Google Scholar, and the bibliographies of retrieved articles.

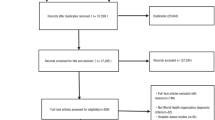

The articles obtained from the literature search were then evaluated according to criteria set out in Figure 1. Criteria for inclusion were: prospective cohort study of the general population of a Western country (countries in Europe or North America, Australia or New Zealand), relevant outcomes, a sample size of at least 200 subjects, and risk estimate based on the incidence of disease instead of the mortality rate of disease. For large cohorts with multiple articles meeting the defined criteria, the most recent article or the article with the most usable information was used. Studies were excluded if they did not provide enough data to allow calculation of unadjusted relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the overweight and obese groups compared to the normal group. Data extracted for study characteristics included study design, country, cohort name, duration of follow-up, number of patients in each study group, age range, gender and ethnicity. Ascertainment of exposure and outcome variables was also recorded. The literature search was conducted by ZA, the decisions on inclusion and exclusion were made by ZA, NB, DPG, CLB and the data were extracted by ZA and DPG.

Meta-analysis

RRs were measured by incidence rate ratios (IRRs) when person-time data were available and by the ratios of proportions (RR-Ps) when person-time data were not available. Study-specific unadjusted RRs on the log scale comparing overweight with normal and obese with normal were weighted by the inverse of their corresponding variances to obtain a pooled RR with 95% CIs. We used the random-effects model to estimate the pooled RR using the maximum likelihood estimation method [28]. The Q statistic was also calculated to assess the homogeneity of RRs (log scale) [28]. Potential publication bias was visually inspected by funnel plots and tested by asymmetry tests [29, 30]; however it was performed only on those meta-analyses which included sufficient number of studies (N>5). We also did various sensitivity analyses stratified on the length of follow-up, age criteria and country to examine the robustness of the results.

WC measurements were considered to be the better risk predictor for some co-morbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke and gallbladder disease [16–24]. Therefore, when the RRs based on WC measurements for these co-morbidities were available, they were pooled separately from those based on BMI and used as the final RRs for these co-morbidities. When both IRR and RR-P estimates were available, both estimates were presented. Final results of RRs were selected based on the number of pooled studies, the duration of study follow-up and the sample size of included studies

Results

A total of 89 relevant and unique studies were identified; several studies featured for more than one co-morbidities. Of the 20 co-morbidities, 18 were identified to have at least one study meeting the inclusion criteria. Some studies were applicable to more than one co-morbidity. No studies were found for dislipidaemia and sleep apnea. The total numbers of studies included for each co-morbidity varied from 1 to 14. Reasons for exclusion are given in Table 1.

The majority of the studies were conducted in US (55%) and in European countries (40%). Study characteristics such as age criteria, study follow-up, ascertainment of exposure and outcome variables were reported by the majority of the studies. However, only a small number of studies reported sample ethnicity and of those, the majority was US studies. Among those US studies, one study (endometrial cancer) was about the black women [31] while for the remaining US studies, the proportion of whites ranged from 81% to 95%. The mean duration of study follow-up was 12.5 (SD = 7.2) years. Over half of the studies (53%) were longer than 10 years while less than 10% of the studies were shorter than 5 years. BMI and WC measurements were clinically measured on 43% of the studies and were self-reported on 56% of the studies while one study did not provide such information. Regarding the ascertainment of cases, 43 (48%) studies identified cases from registry, database centre or clinical evaluation; 34 (38%) studies were based on subject self-reported information with some kind of confirmation method such as medical records review; 6 studies were based on medical records review and 5 studies (4 for asthma and 1 for type-2 diabetes) were relying on self-reported information alone. Note that cancer cases were identified from cancer registry/database on 66% of the studies.

Table 2 summarized our final results. Figures 2 to 18 presented the detailed results including study-specific and pooled estimates. Results from the meta-analysis were summarized in the following sections for each co-morbidity.

Breast cancer

In total, 14 studies were identified for post menopausal breast cancer (Figure 2) [19, 32–44]. The pooled IRRs [95% CI] across categories of WC were 1.13 [1.01–1.07] for overweight and 1.30 [1.17–1.44] for obesity while across categories of BMI the IRRs were 1.08 [1.03–1.14] for overweight and 1.13 [1.05–1.22] for obesity.

Endometrial cancer

In total, 10 studies were identified to meet the inclusion criteria for endometrial cancer (Figure 3) [19, 31, 35, 36, 42, 45–49]. The study on the US black women was not included in the final result as it showed systematic difference from other studies mainly on Caucasian population [31]. The pooled IRRs [95% CI] across categories of WC were 1.15 [1.02–1.30] for overweight and 1.42 [0.80–2.49] for obesity while across categories of BMI IRRs were 1.53 [1.45–1.61] for overweight and 3.22 [2.91–3.56] for obesity.

Ovarian cancer

In total, 9 studies were identified for ovarian cancer (Figure 4) [19, 35, 36, 42, 45, 50–53]. The single IRR [95% CI] across categories of WC were 0.61 [0.35–1.08] for overweight and 1.35 [0.95–1.93] for obesity while pooled IRRs estimates across categories of BMI were 1.18 [1.12–1.23] for overweight and 1.28 [1.20–1.36] for obesity.

Colorectal cancer

A total of 12 studies were identified for colorectal cancer (Figures 5 and 6) [19, 42, 45, 54–62]. For men, the pooled IRRs [95% CI] across categories of WC were 1.88 [1.47–2.41] for overweight and 2.93 [2.31–3.73] for obesity and across categories of BMI were 1.51 [1.37–1.67] for overweight and 1.95 [1.59–2.39] for obesity. For women, the pooled IRRs across categories of WC were 1.25 [0.98–1.59] for overweight and 1.55 [1.27–1.88] for obesity and those across categories of BMI were 1.45 [1.30–1.62] for overweight and 1.66 [1.52–1.81] for obesity.

Esophageal cancer

Only 1 study was identified for esophageal cancer [63]. The study found the risk of cancer based on overweight to be 1.15 [0.97–1.36] and 1.13 [1.02–1.26] for females and males, respectively. The corresponding risks for obesity were 1.20 [0.95–1.53] and 1.21 [0.97–1.52].

Kidney cancer

We identified 5 studies meeting the inclusion criteria relating overweight and obesity to kidney cancer (Figure 7) [42, 45, 57, 64, 65]. The pooled IRRs [95% CI] across categories of BMI for men were 1.40 [1.31–1.49] for overweight and 1.82 [1.61–2.05] for obesity. For women the corresponding risks were 1.82 [1.68–1.98] and 2.64 [2.39–2.90].

Pancreatic cancer

The search identified 6 studies giving information on the risk of pancreatic cancer attributable to overweight and obesity (Figure 8) [42, 45, 66–69]. The pooled IRRs [95% CI] across categories of BMI for men were 1.28 [0.94–1.75] for overweight and 2.29 [1.65–3.19] for obesity. For women the corresponding risks were 1.24 [0.98–1.56] and 1.60 [1.17–2.20].

Prostate cancer

The search identified 8 studies giving information on the risk of prostate cancer attributable to overweight and obesity (Figure 9) [36, 42, 45, 70–74]. The pooled IRRs [95% CI] across categories of BMI were 1.14 [1.00–1.31] for overweight and 1.05 [0.85–1.30] for obesity.

Type II diabetes

Nine studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 10) [19, 75–82]. In general, elevated BMI and WC were significantly associated with type II diabetes in men and women. The pooled IRRs [95% CI] across categories of BMI were 2.40 [2.12–2.72] and 6.74 [5.55–8.19] in men while the corresponding IRRs in women were 3.92 [3.10–4.97] and 12.41 [9.03–17.06]. The association between increased WC and type II diabetes was similar but weaker in comparison with BMI. Only two studies were included in men. The pooled IRRs [95% CI] across categories of WC were 2.36 [1.76–3.15] and 5.67 [4.46–7.20] in men and the pooled RR-Ps [95% CI] based on the same two studies were 2.27 [1.67–3.10] and 5.13 [3.81–6.90], respectively. The pooled RR-Ps were more conservative RR estimates and presented in the summary table (Table 2). The pooled IRRs [95% CI] across categories of WC were 3.40 [2.42–4.78] and 11.10 [8.23–14.96] in women.

Hypertension

Four studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 11) [19, 83–85]. The pooled IRR [95% CI] estimates for hypertension across categories BMI for men were 1.28 [1.10–1.50] for overweight and 1.84 [1.51–2.24] for obesity. The corresponding figures for females were 1.65 [1.24–2.19] and 2.42 [1.59–3.67]. The single IRR estimate based on WC for women was 1.38 [1.27–1.51] for overweight and 1.90 [1.77–2.03] for obesity.

Stroke

Seven studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 12) [86–92]. The pooled RR-P [95% CI] estimates for stroke across categories BMI for men were 1.23 [1.13–1.34] for overweight and 1.51 [1.33–1.72] for obesity. The corresponding results for females were 1.15 [1.00–1.32] and 1.49 [1.27–1.74].

Coronary Artery Disease

Eleven studies were identified with evidence for coronary artery disease related to obesity (Figures 13 and 14) [20, 21, 79, 91, 93–99]. The pooled RR-P estimates for coronary artery disease across categories of WC were more conservative RR estimates for men than the corresponding IRR estimates and thus were presented in the summary table (Table 2). The RR-P [95% CI] estimates for WC were 1.41 [1.16–1.72] for overweight and 1.81 [1.45–2.25] for obesity. The corresponding results for BMI were 1.29 [1.18–1.41] and 1.72 [1.51–1.96]. While the pooled RR-P estimates based on BMI measurements for women were generated from 4 studies, the IRR estimates were generated from 2 different studies with longer follow-up. Thus, the IRR estimates were the RR estimates for women presented in the summary table (Table 2). The estimates were 1.80 [1.64–1.98] for overweight and 3.10 [2.81–3.43] for obesity based on BMI measurements and 1.82 [1.41–2.36] and 2.69 [2.05–3.53] for WC.

Congestive Heart Failure

Four studies were identified with evidence for congestive heart failure related to obesity (Figure 15) [91, 100–102]. The pooled IRR [95% CI] estimates for congestive heart failure across categories of BMI for men were 1.31 [0.96–1.79] for overweight and 1.79 [1.24–2.59] for obesity. The pooled RR-P estimates for females based on 3 studies were 1.27 [0.68–2.37] and 1.78 [1.07–2.95], which were chosen as the RR estimates over the IRR estimates based on 2 studies.

Asthma

Four studies were identified with evidence for asthma related to obesity (Figure 16) [103–106]. The pooled RR-P [95% CI] estimates for asthma across categories of BMI for men were 1.20 [1.08–1.33] for overweight and 1.43 [1.14–1.79] for obese. The corresponding numbers for females were 1.25 [1.05–1.49] and 1.78 [1.36–2.32].

Chronic back pain

Only 1 study was identified to meet the inclusion criteria for chronic back pain [107]. The study identified the association for the overweight and obesity with early retirement due to chronic back pain. The study found RR-P [95% CI] estimates across categories of BMI of chronic back pain based on overweight to be 1.59 [1.34–1.89] and for obesity 2.81 [2.27–3.48].

Osteoarthritis

We identified three studies meeting the inclusion criteria relating overweight and obesity to osteoarthritis (Figure 17) [108–110]. The studies identified the risk of joint replacement attributable to being overweight and obese. The pooled IRRs [95% CI] across categories of BMI for men were 2.76 [2.05–3.70] for overweight and 4.20 [2.76–6.41] for obesity. For women, the RR-P estimates were more conservative RR estimate and they were 1.80 [1.75–1.85] and 1.96 [1.88–2.04].

Pulmonary embolism

Only 1 study was identified to meet the inclusion criteria for pulmonary embolism [111]. The study found IRR [95% CI] across categories of BMI of Pulmonary embolism based on overweight to be 1.91 [1.39–2.64] and for obesity 3.51 [2.61–4.73].

Gallbladder disease

We identified four studies meeting the inclusion criteria relating overweight and obesity gallbladder disease (Figure 18) [59, 112–114]. The pooled IRRs [95% CI] across categories of WC for men were 1.63 [1.42–1.88] for overweight and 2.51 [2.16–2.91] for obesity. The corresponding pooled RR-Ps were 1.61 [1.40–1.85] and 2.38 [2.06–2.75]. Thus, the pooled RR-Ps were more conservative RR estimates and presented in Table 2. Across categories of BMI, the pooled IRR and RR-P estimates were presented as the RR estimates in Table 2 and they were 1.09 [0.87–1.37] for overweight and 1.43 [1.04–1.96] for obesity. For women only estimates for BMI were identified giving pooled IRR and RR-P estimates of 1.44 [1.05–1.98] for overweight and 2.32 [1.17–4.57] for obesity.

Potential publication bias was assessed for post-menopausal breast cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer for females and prostate cancer. We found some evidence of funnel-plot asymmetry for obesity in prostate cancer where bigger studies tended to show stronger positive association than smaller studies. No evidence of publication bias was found in the other meta-analyses.

Our sensitivity analyses showed that our results were in general robust with the following exceptions. For ovarian cancer, associations for both overweight and obesity were slightly weaker in US studies compared to European studies. Similar country differences were found in pancreatic cancers; in addition, weaker associations were observed in older population. Studies with shorter follow-up time and of older population showed slightly weaker association of obesity with prostate cancer. In coronary artery disease for females, studies with shorter follow-up showed weaker associations of both overweight and obese. In coronary artery disease for males, weaker associations were observed in US and Canadian studies. Studies of post-menopausal and senior women on congestive heart failure showed weaker associations for both overweight and obesity.

Discussion

We have comprehensively reviewed 20 co-morbidities for high quality cohort studies which determine risk factors associated with overweight or obesity. 18 co-morbidities were identified and meta-analysis was performed where at least 1 study was found. A summary of the results can be found in Table 2.

There are a number of alternative meta-analyses with which we can compare our results. For example, recent meta-analyses have been reported in diabetes [115, 116], cardiovascular diseases [117], coronary heart disease [118], hypertension [116], cancer [119], colorectal cancer [120–122], gallbladder cancer [123], pancreatic cancer [124], ovarian cancer [125] and asthma [126]. However, each study uses different definitions of overweight and obesity, includes varying quality of study designs, uses different methods for meta-analysis and ultimately only focuses on individual co-morbidities. Hence, the objective of our study is not only to provide up to date estimates of the risk of all possible co-morbidities attributable to overweight and obesity, but also to do it using consistent definitions and methodology.

In assessing whether obesity is related to a given co-morbidity, the occurrence timing of co-morbidities with respect to exposure of obesity is important in determining the causal pathway. Therefore, we included only the prospective cohort studies and excluded the cross-sectional studies and case control studies to minimize the associated potential biases. In addition, WC measurements were considered to be the better risk predictor for type II diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke and gallbladder disease [16–24]. In our studies, the risk for type II diabetes, female hypertension, coronary artery disease, and male gallbladder disease were estimated based on WC measurements.

Some limitations are worthy of further consideration. Firstly, other variables not included in our analysis might potentially confound our results. Most important is the exclusion of the level of physical inactivity which is a known risk factor for some co-morbidities and related to overweight and obesity [127]. Physical inactivity is often poorly reported and requiring its inclusion would have reduced the number of included studies. Secondly, for certain co-morbidities, we only identified 1 or 2 prospective cohort studies that adopted the WC measurements as the risk predictor. Further studies are required to determine the association between WC and some co-morbidities before an estimate of the risk can be calculated through a meta-analysis. Thirdly, given the sizable literature and that we were searching for non RCT studies for which search filters are more complex, we determined to use Medline and Embase as the electronic databases, and complement the search with checking reference lists and thorough searching the internet. We did not search other databases such as CINHAL, HealthSTAR, AMED, and BIOSIS. Therefore, bias might have occurred due to our search strategy. However, given the nature of the studies we are looking for, i.e., prospective cohort studies with high quality, we consider our search within Medline and Embase sufficient. Lastly, due to the small number of studies for most co-morbidities, assessment of potential publication bias was infeasible. However, we did not find evidence of publication bias in those meta-analyses where the number of studies was relatively large except for prostate cancer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive estimate of the incidence of 18 co-morbidities attributable to overweight and obesity using standardized and consistent definitions and methodologies. Our findings confirm that overweight and obesity carry a profound health burden and will have a significant impact on health expenditures.

Abbreviations

- WC:

-

Waist Circumference

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- RR:

-

Relative Risk

- IRR:

-

Incidence Rate Ratio

- RR-P:

-

Relative Risk calculated from the ratio of Proportions

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization.

References

Haslam DW, James WP: Obesity. Lancet. 2005, 366: 1197-1209. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1.

McTigue KM, Hess R, Ziouras J: Obesity in older adults: a systematic review of the evidence for diagnosis and treatment. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006, 14 (9): 1485-1497. 10.1038/oby.2006.171.

Pi-Sunyer FX: Comorbidities of overweight and obesity: current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999, 31 (11 Suppl): S602-8.

Birmingham CL, Muller JL, Palepu A, Spinelli JJ, Anis AH: The cost of obesity in Canada. CMAJ. 1999, 160 (4): 483-488.

Katzmarzyk PT, Janssen I: The economic costs associated with physical inactivity and obesity in Canada: an update. Can J Appl Physiol. 2004, 29 (1): 90-115.

McCormick B, Stone I, Corporate Analytical T: Economic costs of obesity and the case for government intervention. Obes Rev. 2007, 8 (Suppl 1): 161-164. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00337.x.

Hartemink N, Boshuizen HC, Nagelkerke NJ, Jacobs MA, van Houwelingen HC: Combining risk estimates from observational studies with different exposure cutpoints: a meta-analysis on body mass index and diabetes type 2. Am J Epidemiol. 2006, 163 (11): 1042-1052. 10.1093/aje/kwj141.

Asia Pacific Cohort Studies, Collaboration: Central obesity and risk of cardiovascular disease in the Asia Pacific Region. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006, 15 (3): 287-292.

Ni Mhurchu C, Rodgers A, Pan WH, Gu DF, Woodward M, Asia Pacific Cohort Studies, Collaboration: Body mass index and cardiovascular disease in the Asia-Pacific Region: an overview of 33 cohorts involving 310 000 participants. Int J Epidemiol. 2004, 33 (4): 751-758. 10.1093/ije/dyh163.

Bergstrom A, Pisani P, Tenet V, Wolk A, Adami HO: Overweight as an avoidable cause of cancer in Europe. Int J Cancer. 2001, 91 (3): 421-430. 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::AID-IJC1053>3.0.CO;2-T.

Key TJ, Appleby PN, Reeves GK, Roddam A, Dorgan JF, Longcope C, Stanczyk FZ, Stephenson HE, Falk RT, Miller R, Schatzkin A, Allen DS, Fentiman IS, Key TJ, Wang DY, Dowsett M, Thomas HV, Hankinson SE, Toniolo P, Akhmedkhanov A, Koenig K, Shore RE, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Berrino F, Muti P, Micheli A, Krogh V, Sieri S, Pala V, Venturelli E, Secreto G, Barrett-Connor E, Laughlin GA, Kabuto M, Akiba S, Stevens RG, Neriishi K, Land CE, Cauley JA, Kuller LH, Cummings SR, Helzlsouer KJ, Alberg AJ, Bush TL, Comstock GW, Gordon GB, Miller SR, Longcope C, Endogenous Hormones Breast Cancer Collaborative, Group: Body mass index, serum sex hormones, and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003, 95 (16): 1218-1226.

Harvie M, Hooper L, Howell AH: Central obesity and breast cancer risk: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2003, 4 (3): 157-173. 10.1046/j.1467-789X.2003.00108.x.

Kubo A, Corley DA: Body mass index and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus or gastric cardia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006, 15 (5): 872-878. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0860.

Berrington de Gonzalez A, Sweetland S, Spencer E: A meta-analysis of obesity and the risk of pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003, 89 (3): 519-523. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601140.

MacInnis RJ, English DR: Body size and composition and prostate cancer risk: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2006, 17 (8): 989-1003. 10.1007/s10552-006-0049-z.

Ardern CI, Katzmarzyk PT, Janssen I, Ross R: Discrimination of health risk by combined body mass index and waist circumference. Obes Res. 2003, 11 (1): 135-142. 10.1038/oby.2003.22.

Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R: Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004, 79 (3): 379-384.

Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R: Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk: evidence in support of current National Institutes of Health guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2002, 162 (18): 2074-2079. 10.1001/archinte.162.18.2074.

Folsom AR, Kushi LH, Anderson KE, Mink PJ, Olson JE, Hong CP, Sellers TA, Lazovich D, Prineas RJ: Associations of general and abdominal obesity with multiple health outcomes in older women: the Iowa Women's Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000, 160 (14): 2117-2128. 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2117.

Rexrode KM, Carey VJ, Hennekens CH, Walters EE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Manson JE: Abdominal adiposity and coronary heart disease in women. JAMA. 1998, 280 (21): 1843-1848. 10.1001/jama.280.21.1843.

Rexrode KM, Buring JE, Manson JE: Abdominal and total adiposity and risk of coronary heart disease in men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001, 25 (7): 1047-1056. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801615.

Iwao S, Iwao N, Muller DC, Elahi D, Shimokata H, Andres R: Does waist circumference add to the predictive power of the body mass index for coronary risk?. Obes Res. 2001, 9 (11): 685-695. 10.1038/oby.2001.93.

Zhu S, Wang Z, Heshka S, Heo M, Faith MS, Heymsfield SB: Waist circumference and obesity-associated risk factors among whites in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: clinical action thresholds. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002, 76 (4): 743-749.

Chan JM, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC: Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care. 1994, 17 (9): 961-969. 10.2337/diacare.17.9.961.

World Health Organization: Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. 2000, World Health Organization Technical Report Series No. 894; Geneva

Health Canada: Canadian Guidelines for Body Weight Classification in Adults. Ottawa. 2003, [http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/nutrition/weights-poids/guide-ld-adult/weight_book_tc-livres_des_poids_tm-eng.php]

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL: Global burden of disease and risk factors. 2006, New York: The World Bank and Oxford University Press

DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986, 7 (3): 177-188. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2.

Sterne JA, Egger M: Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001, 54 (10): 1046-1055. 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00377-8.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997, 315 (7109): 629-634.

Wise LA, Palmer JR, Spiegelman D, Harlow BL, Stewart EA, Adams-Campbell LL, Rosenberg L: Influence of body size and body fat distribution on risk of uterine leiomyomata in U.S. black women. Epidemiology. 2005, 16 (3): 346-354. 10.1097/01.ede.0000158742.11877.99.

Sellers TA, Davis J, Cerhan JR, Vierkant RA, Olson JE, Pankratz VS, Potter JD, Folsom AR: Interaction of waist/hip ratio and family history on the risk of hormone receptor-defined breast cancer in a prospective study of postmenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 2002, 155 (3): 225-233. 10.1093/aje/155.3.225.

Sweeney C, Blair CK, Anderson KE, Lazovich D, Folsom AR: Risk factors for breast cancer in elderly women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 160 (9): 868-875. 10.1093/aje/kwh276.

Dirx MJ, Voorrips LE, Goldbohm RA, Brandt van den PA: Baseline recreational physical activity, history of sports participation, and postmenopausal breast carcinoma risk in the Netherlands Cohort Study. Cancer. 2001, 92 (6): 1638-1649. 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6<1638::AID-CNCR1490>3.0.CO;2-Q.

Tornberg SA, Carstensen JM: Relationship between Quetelet's index and cancer of breast and female genital tract in 47,000 women followed for 25 years. Br J Cancer. 1994, 69 (2): 358-361.

Jonsson F, Wolk A, Pedersen NL, Lichtenstein P, Terry P, Ahlbom A, Feychting M: Obesity and hormone-dependent tumors: cohort and co-twin control studies based on the Swedish Twin Registry. Int J Cancer. 2003, 106 (4): 594-599. 10.1002/ijc.11266.

Silvera SA, Jain M, Howe GR, Miller AB, Rohan TE: Energy balance and breast cancer risk: a prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006, 97 (1): 97-106. 10.1007/s10549-005-9098-3.

Chang SC, Ziegler RG, Dunn B, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Lacey JV, Huang WY, Schatzkin A, Reding D, Hoover RN, Hartge P, Leitzmann MF: Association of energy intake and energy balance with postmenopausal breast cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006, 15 (2): 334-341. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0479.

Suzuki R, Rylander-Rudqvist T, Ye W, Saji S, Wolk A: Body weight and postmenopausal breast cancer risk defined by estrogen and progesterone receptor status among Swedish women: A prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2006, 119 (7): 1683-1689. 10.1002/ijc.22034.

Tehard B, Lahmann PH, Riboli E, Clavel-Chapelon F: Anthropometry, breast cancer and menopausal status: use of repeated measurements over 10 years of follow-up-results of the French E3N women's cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2004, 111 (2): 264-269. 10.1002/ijc.20213.

McTiernan A, Kooperberg C, White E, Wilcox S, Coates R, Adams-Campbell LL, Woods N, Ockene J, Women's Health Initiative Cohort Study: Recreational physical activity and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative Cohort Study. JAMA. 2003, 290 (10): 1331-1336. 10.1001/jama.290.10.1331.

Lukanova A, Bjor O, Kaaks R, Lenner P, Lindahl B, Hallmans G, Stattin P: Body mass index and cancer: results from the Northern Sweden Health and Disease Cohort. Int J Cancer. 2006, 118 (2): 458-466. 10.1002/ijc.21354.

Barlow WE, White E, Ballard-Barbash R, Vacek PM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Carney PA, Tice JA, Buist DS, Geller BM, Rosenberg R, Yankaskas BC, Kerlikowske K: Prospective breast cancer risk prediction model for women undergoing screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006, 98 (17): 1204-1214.

Huang Z, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Hankinson SE: Waist circumference, waist:hip ratio, and risk of breast cancer in the Nurses' Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999, 150 (12): 1316-1324.

Rapp K, Schroeder J, Klenk J, Stoehr S, Ulmer H, Concin H, Diem G, Oberaigner W, Weiland SK: Obesity and incidence of cancer: a large cohort study of over 145,000 adults in Austria. Br J Cancer. 2005, 93 (9): 1062-1067. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602819.

Schouten LJ, Goldbohm RA, Brandt van den PA: Anthropometry, physical activity, and endometrial cancer risk: results from the Netherlands Cohort Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004, 96 (21): 1635-1638.

Bjorge T, Engeland A, Tretli S, Weiderpass E: Body size in relation to cancer of the uterine corpus in 1 million Norwegian women. Int J Cancer. 2007, 120 (2): 378-383. 10.1002/ijc.22260.

Silvera SA, Rohan TE, Jain M, Terry PD, Howe GR, Miller AB: Glycaemic index, glycaemic load and risk of endometrial cancer: a prospective cohort study. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8 (7): 912-919. 10.1079/PHN2005741.

Folsom AR, Demissie Z, Harnack L, Iowa Women's Health Study: Glycemic index, glycemic load, and incidence of endometrial cancer: the Iowa women's health study. Nutr Cancer. 2003, 46 (2): 119-124. 10.1207/S15327914NC4602_03.

Engeland A, Tretli S, Bjorge T: Height, body mass index, and ovarian cancer: a follow-up of 1.1 million Norwegian women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003, 95 (16): 1244-1248.

Anderson JP, Ross JA, Folsom AR: Anthropometric variables, physical activity, and incidence of ovarian cancer: The Iowa Women's Health Study. Cancer. 2004, 100 (7): 1515-1521. 10.1002/cncr.20146.

Schouten LJ, Goldbohm RA, Brandt van den PA: Height, weight, weight change, and ovarian cancer risk in the Netherlands cohort study on diet and cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2003, 157 (5): 424-433. 10.1093/aje/kwf224.

Fairfield KM, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Manson JE, Speizer FE, Hankinson SE: Obesity, weight gain, and ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2002, 100 (2): 288-296. 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02053-7.

MacInnis RJ, English DR, Hopper JL, Haydon AM, Gertig DM, Giles GG: Body size and composition and colon cancer risk in men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004, 13 (4): 553-559.

Giovannucci E, Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC: Physical activity, obesity, and risk for colon cancer and adenoma in men. Ann Intern Med. 1995, 122 (5): 327-334.

Moore LL, Bradlee ML, Singer MR, Splansky GL, Proctor MH, Ellison RC, Kreger BE: BMI and waist circumference as predictors of lifetime colon cancer risk in Framingham Study adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004, 28 (4): 559-567. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802606.

Pischon T, Lahmann PH, Boeing H, Friedenreich C, Norat T, Tjonneland A, Halkjaer J, Overvad K, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault MC, Guernec G, Bergmann MM, Linseisen J, Becker N, Trichopoulou A, Trichopoulos D, Sieri S, Palli D, Tumino R, Vineis P, Panico S, Peeters PH, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Boshuizen HC, Van Guelpen B, Palmqvist R, Berglund G, Gonzalez CA, Dorronsoro M, Barricarte A, Navarro C, Martinez C, Quiros JR, Roddam A, Allen N, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Ferrari P, Kaaks R, Slimani N, Riboli E: Body size and risk of colon and rectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006, 98 (13): 920-931.

Ford ES: Body mass index and colon cancer in a national sample of adult US men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 1999, 150 (4): 390-398.

Engeland A, Tretli S, Austad G, Bjorge T: Height and body mass index in relation to colorectal and gallbladder cancer in two million Norwegian men and women. Cancer Causes Control. 2005, 16 (8): 987-996. 10.1007/s10552-005-3638-3.

Martinez ME, Giovannucci E, Spiegelman D, Hunter DJ, Willett WC, Colditz GA: Leisure-time physical activity, body size, and colon cancer in women. Nurses' Health Study Research Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997, 89 (13): 948-955. 10.1093/jnci/89.13.948.

Lin J, Zhang SM, Cook NR, Rexrode KM, Lee IM, Buring JE: Body mass index and risk of colorectal cancer in women (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2004, 15 (6): 581-589. 10.1023/B:CACO.0000036168.23351.f1.

McCarl M, Harnack L, Limburg PJ, Anderson KE, Folsom AR: Incidence of colorectal cancer in relation to glycemic index and load in a cohort of women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006, 15 (5): 892-896. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0700.

Engeland A, Tretli S, Bjorge T: Height and body mass index in relation to esophageal cancer; 23-year follow-up of two million Norwegian men and women. Cancer Causes Control. 2004, 15 (8): 837-843. 10.1023/B:CACO.0000043434.21558.ea.

Flaherty KT, Fuchs CS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE, Willett WC, Curhan GC: A prospective study of body mass index, hypertension, and smoking and the risk of renal cell carcinoma (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2005, 16 (9): 1099-1106. 10.1007/s10552-005-0349-8.

Bjorge T, Tretli S, Engeland A: Relation of height and body mass index to renal cell carcinoma in two million Norwegian men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 160 (12): 1168-1176. 10.1093/aje/.

Michaud DS, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Fuchs CS: Physical activity, obesity, height, and the risk of pancreatic cancer. JAMA. 2001, 286 (8): 921-929. 10.1001/jama.286.8.921.

Larsson SC, Permert J, Hakansson N, Naslund I, Bergkvist L, Wolk A: Overall obesity, abdominal adiposity, diabetes and cigarette smoking in relation to the risk of pancreatic cancer in two Swedish population-based cohorts. Br J Cancer. 2005, 93 (11): 1310-1315. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602868.

Patel AV, Rodriguez C, Bernstein L, Chao A, Thun MJ, Calle EE: Obesity, recreational physical activity, and risk of pancreatic cancer in a large U.S. Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14 (2): 459-466. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0583.

Sinner PJ, Schmitz KH, Anderson KE, Folsom AR: Lack of association of physical activity and obesity with incident pancreatic cancer in elderly women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14 (6): 1571-1573. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0036.

Engeland A, Tretli S, Bjorge T: Height, body mass index, and prostate cancer: a follow-up of 950000 Norwegian men. Br J Cancer. 2003, 89 (7): 1237-1242. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601206.

Nilsen TI, Vatten LJ: Anthropometry and prostate cancer risk: a prospective study of 22,248 Norwegian men. Cancer Causes Control. 1999, 10 (4): 269-275. 10.1023/A:1008967330619.

Zeegers MP, Dirx MJ, Brandt van den PA: Physical activity and the risk of prostate cancer in the Netherlands cohort study, results after 9.3 years of follow-up. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14 (6): 1490-1495. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0771.

Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC: Height, body weight, and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997, 6 (8): 557-563.

Habel LA, Eeden Van Den SK, Friedman GD: Body size, age at shaving initiation, and prostate cancer in a large, multiracial cohort. Prostate. 2000, 43 (2): 136-143. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(20000501)43:2<136::AID-PROS8>3.0.CO;2-L.

Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz G, Liu S, Solomon CG, Willett WC: Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med. 2001, 345 (11): 790-797. 10.1056/NEJMoa010492.

Weinstein AR, Sesso HD, Lee IM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, Gaziano JM: Relationship of physical activity vs body mass index with type 2 diabetes in women. JAMA. 2004, 292 (10): 1188-1194. 10.1001/jama.292.10.1188.

Meisinger C, Doring A, Thorand B, Heier M, Lowel H: Body fat distribution and risk of type 2 diabetes in the general population: are there differences between men and women? The MONICA/KORA Augsburg cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006, 84 (3): 483-489.

Carey VJ, Walters EE, Colditz GA, Solomon CG, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Speizer FE, Manson JE: Body fat distribution and risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. The Nurses' Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997, 145 (7): 614-619.

Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Walker M: Overweight and obesity and weight change in middle aged men: impact on cardiovascular disease and diabetes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005, 59 (2): 134-139. 10.1136/jech.2003.015651.

Koh-Banerjee P, Wang Y, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, Willett WC, Rimm EB: Changes in body weight and body fat distribution as risk factors for clinical diabetes in US men. Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 159 (12): 1150-1159. 10.1093/aje/kwh167.

Oguma Y, Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS, Lee IM: Weight change and risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Obes Res. 2005, 13 (5): 945-951. 10.1038/oby.2005.109.

Wang Y, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB: Comparison of abdominal adiposity and overall obesity in predicting risk of type 2 diabetes among men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005, 81 (3): 555-563.

Hu G, Barengo NC, Tuomilehto J, Lakka TA, Nissinen A, Jousilahti P: Relationship of physical activity and body mass index to the risk of hypertension: a prospective study in Finland. Hypertension. 2004, 43 (1): 25-30. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107400.72456.19.

Radi S, Lang T, Lauwers-Cances V, Chatellier G, Fauvel JP, Larabi L, De Gaudemaris R, IHPAF Group: One-year hypertension incidence and its predictors in a working population: the IHPAF study. J Hum Hypertens. 2004, 18 (7): 487-494. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001682.

Huang Z, Willett WC, Manson JE, Rosner B, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE, Colditz GA: Body weight, weight change, and risk for hypertension in women. Ann Intern Med. 1998, 128 (2): 81-88.

Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Berger K, Kase CS, Rexrode KM, Cook NR, Buring JE, Manson JE: Body mass index and the risk of stroke in men. Arch Intern Med. 2002, 162 (22): 2557-2562. 10.1001/archinte.162.22.2557.

Jood K, Jern C, Wilhelmsen L, Rosengren A: Body mass index in mid-life is associated with a first stroke in men: a prospective population study over 28 years. Stroke. 2004, 35 (12): 2764-2769. 10.1161/01.STR.0000147715.58886.ad.

Shaper AG, Wannamethee SG, Walker M: Body weight: implications for the prevention of coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus in a cohort study of middle aged men. BMJ. 1997, 314 (7090): 1311-1317.

Murphy NF, MacIntyre K, Stewart S, Hart CL, Hole D, McMurray JJ: Long-term cardiovascular consequences of obesity: 20-year follow-up of more than 15 000 middle-aged men and women (the Renfrew-Paisley study). Eur Heart J. 2006, 27 (1): 96-106. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi506.

Rexrode KM, Hennekens CH, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Rich-Edwards JW, Speizer FE, Manson JE: A prospective study of body mass index, weight change, and risk of stroke in women. JAMA. 1997, 277 (19): 1539-1545. 10.1001/jama.277.19.1539.

Wessel TR, Arant CB, Olson MB, Johnson BD, Reis SE, Sharaf BL, Shaw LJ, Handberg E, Sopko G, Kelsey SF, Pepine CJ, Merz NB: Relationship of physical fitness vs body mass index with coronary artery disease and cardiovascular events in women. JAMA. 2004, 292 (10): 1179-1187. 10.1001/jama.292.10.1179.

Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Rexrode KM, Kase CS, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE: Prospective study of body mass index and risk of stroke in apparently healthy women. Circulation. 2005, 111 (15): 1992-1998. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161822.83163.B6.

Jonsson S, Hedblad B, Engstrom G, Nilsson P, Berglund G, Janzon L: Influence of obesity on cardiovascular risk. Twenty-three-year follow-up of 22,025 men from an urban Swedish population. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002, 26 (8): 1046-1053. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802060.

Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Sullivan L, Parise H, Kannel WB: Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Arch Intern Med. 2002, 162 (16): 1867-1872. 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1867.

St-Pierre AC, Cantin B, Mauriege P, Bergeron J, Dagenais GR, Despres JP, Lamarche B: Insulin resistance syndrome, body mass index and the risk of ischemic heart disease. CMAJ. 2005, 172 (10): 1301-1305.

Seeman T, Mendes de Leon C, Berkman L, Ostfeld A: Risk factors for coronary heart disease among older men and women: a prospective study of community-dwelling elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1993, 138 (12): 1037-1049.

Kannel WB, Wilson PW, Nam BH, D'Agostino RB: Risk stratification of obesity as a coronary risk factor. Am J Cardiol. 2002, 90 (7): 697-701. 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)02592-4.

Tuomilehto J, Salonen JT, Marti B, Jalkanen L, Puska P, Nissinen A, Wolf E: Body weight and risk of myocardial infarction and death in the adult population of eastern Finland. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987, 295 (6599): 623-627.

Li TY, Rana JS, Manson JE, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rexrode KM, Hu FB: Obesity as compared with physical activity in predicting risk of coronary heart disease in women. Circulation. 2006, 113 (4): 499-506. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.574087.

Rea TD, Psaty BM, Heckbert SR, Cushman M, Meilahn E, Olson JL, Lemaitre RN, Smith NL, Sotoodehnia N, Chaves PH: Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of incident congestive heart failure: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2003, 12 (4): 341-350.

Kenchaiah S, Evans JC, Levy D, Wilson PW, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Vasan RS: Obesity and the risk of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347 (5): 305-313. 10.1056/NEJMoa020245.

Bibbins-Domingo K, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Barrett-Connor E, Hulley SB, Grady D, Shlipak MG: Predictors of heart failure among women with coronary disease. Circulation. 2004, 110 (11): 1424-1430. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000141726.01302.83.

Chen Y, Dales R, Tang M, Krewski D: Obesity may increase the incidence of asthma in women but not in men: longitudinal observations from the Canadian National Population Health Surveys. Am J Epidemiol. 2002, 155 (3): 191-197. 10.1093/aje/155.3.191.

Nystad W, Meyer HE, Nafstad P, Tverdal A, Engeland A: Body mass index in relation to adult asthma among 135,000 Norwegian men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 160 (10): 969-976. 10.1093/aje/kwh303.

Ford ES, Mannino DM, Redd SC, Mokdad AH, Mott JA: Body mass index and asthma incidence among USA adults. Eur Respir J. 2004, 24 (5): 740-744. 10.1183/09031936.04.00088003.

Camargo CA, Weiss ST, Zhang S, Willett WC, Speizer FE: Prospective study of body mass index, weight change, and risk of adult-onset asthma in women. Arch Intern Med. 1999, 159 (21): 2582-2588. 10.1001/archinte.159.21.2582.

Hagen KB, Tambs K, Bjerkedal T: A prospective cohort study of risk factors for disability retirement because of back pain in the general working population. Spine. 2002, 27 (16): 1790-1796. 10.1097/00007632-200208150-00019.

Jarvholm B, Lewold S, Malchau H, Vingard E: Age, bodyweight, smoking habits and the risk of severe osteoarthritis in the hip and knee in men. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005, 20 (6): 537-542. 10.1007/s10654-005-4263-x.

Flugsrud GB, Nordsletten L, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Engeland A, Meyer HE: The impact of body mass index on later total hip arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis: a cohort study in 1.2 million persons. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54 (3): 802-807. 10.1002/art.21659.

Karlson EW, Mandl LA, Aweh GN, Sangha O, Liang MH, Grodstein F: Total hip replacement due to osteoarthritis: the importance of age, obesity, and other modifiable risk factors. Am J Med. 2003, 114 (2): 93-98. 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01447-X.

Goldhaber SZ, Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Willett WC, Hennekens CH: A prospective study of risk factors for pulmonary embolism in women. JAMA. 1997, 277 (8): 642-645. 10.1001/jama.277.8.642.

Tsai CJ, Leitzmann MF, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL: Prospective study of abdominal adiposity and gallstone disease in US men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004, 80 (1): 38-44.

Boland LL, Folsom AR, Rosamond WD, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators: Hyperinsulinemia, dyslipidemia, and obesity as risk factors for hospitalized gallbladder disease. A prospective study. Ann Epidemiol. 2002, 12 (2): 131-140. 10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00260-5.

Layde PM, Vessey MP, Yeates D: Risk factors for gall-bladder disease: a cohort study of young women attending family planning clinics. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1982, 36 (4): 274-278. 10.1136/jech.36.4.274.

Vazquez G, Duval S, Jacobs DR, Silventoinen K: Comparison of body mass index, waist circumference, and waist/hip ratio in predicting incident diabetes: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007, 29: 115-128. 10.1093/epirev/mxm008.

Decoda Study G, Nyamdorj R, Qiao Q, Lam TH, Tuomilehto J, Ho SY, Pitkaniemi J, Nakagami T, Mohan V, Janus ED, Ferreira SR: BMI compared with central obesity indicators in relation to diabetes and hypertension in Asians. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008, 16 (7): 1622-1635. 10.1038/oby.2008.73.

de Koning L, Merchant AT, Pogue J, Anand SS: Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular events: meta-regression analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J. 2007, 28 (7): 850-856. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm026.

Bogers RP, Bemelmans WJ, Hoogenveen RT, Boshuizen HC, Woodward M, Knekt P, van Dam RM, Hu FB, Visscher TL, Menotti A, Thorpe RJ, Jamrozik K, Calling S, Strand BH, Shipley MJ, for the BMI-CHD Collaboration, Investigators: Association of overweight with increased risk of coronary heart disease partly independent of blood pressure and cholesterol levels: a meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies including more than 300 000 persons. Arch Intern Med. 2007, 167 (16): 1720-1728. 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1720.

Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M: Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies.[see comment]. Lancet. 2008, 371 (9612): 569-578. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X.

Moghaddam AA, Woodward M, Huxley R: Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of 31 studies with 70,000 events. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007, 16 (12): 2533-2547. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0708.

Larsson SC, Wolk A: Obesity and colon and rectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007, 86 (3): 556-565.

Dai Z, Xu YC, Niu L: Obesity and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. World J Gastroenterol. 2007, 13 (31): 4199-4206.

Larsson SC, Wolk A: Obesity and the risk of gallbladder cancer: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2007, 96 (9): 1457-1461.

Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A: Body mass index and pancreatic cancer risk: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cancer. 2007, 120 (9): 1993-1998. 10.1002/ijc.22535.

Olsen CM, Green AC, Whiteman DC, Sadeghi S, Kolahdooz F, Webb PM: Obesity and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2007, 43 (4): 690-709. 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.11.010.

Beuther DA, Sutherland ER: Overweight, obesity, and incident asthma: a meta-analysis of prospective epidemiologic studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007, 175 (7): 661-666. 10.1164/rccm.200611-1717OC.

Katzmarzyk PT, Janssen I, Ardern CI: Physical inactivity, excess adiposity and premature mortality. Obes Rev. 2003, 4 (4): 257-290. 10.1046/j.1467-789X.2003.00120.x.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/9/88/prepub

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is part of larger project funded by Sanofi-aventis Canada Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

This manuscript is part of larger project funded by sanofi-aventis Canada Inc.

Authors' contributions

ZA conducted literature search. ZA, NB, DPG, CLB evaluated the study articles and made decisions on inclusion and exclusion of the articles. DPG, WZ, AHA performed statistical analyses. All authors (DPG, WZ, NB, ZA, CLB, AHA) were involved in the manuscript development and its revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Guh, D.P., Zhang, W., Bansback, N. et al. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 9, 88 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-88

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-88