Abstract

Background

The TGACG-binding (TGA) family has 10 members that play vital roles in Arabidopsis thaliana defense responses and development. However, their involvement in controlling flowering time remains largely unknown and requires further investigation.

Results

To study the role of TGA7 during floral transition, we first investigated the tga7 mutant, which displayed a delayed-flowering phenotype under both long-day and short-day conditions. We then performed a flowering genetic pathway analysis and found that both autonomous and thermosensory pathways may affect TGA7 expression. Furthermore, to reveal the differential gene expression profiles between wild-type (WT) and tga7, cDNA libraries were generated for WT and tga7 mutant seedlings at 9 days after germination. For each library, deep-sequencing produced approximately 6.67 Gb of high-quality sequences, with the majority (84.55 %) of mRNAs being between 500 and 3,000 nt. In total, 325 differentially expressed genes were identified between WT and tga7 mutant seedlings. Among them, four genes were associated with flowering time control. The differential expression of these four flowering-related genes was further validated by qRT-PCR.

Conclusions

Among these four differentially expressed genes associated with flowering time control, FLC and MAF5 may be mainly responsible for the delayed-flowering phenotype in tga7, as TGA7 expression was regulated by autonomous pathway genes. These results provide a framework for further studying the role of TGA7 in promoting flowering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

TGACG-binding (TGA) transcription factors (TFs) belong to the bZIP TF family. There are 10 members in the TGA family, and they play essential roles in Arabidopsis thaliana defense responses and development [1,2,3]. These TGAs can interact with non-repressor of pathogenesis-related gene 1 (NPR1), which is involved in salicylic acid (SA)-mediated gene expression (similar to PR-1) and disease resistance [4, 5]. These TGAs bind to cis-regulatory TGACG elements [6], and this element is present in PR1 promoters, which are required for PR1 gene expression in response to SA and interact with NPR1 [4, 7,8,9]. However, NPR1 cannot bind directly to the PR-1 promoter, but is recruited to the promoter by its physical interaction with TGAs to regulate the expression of PR-1 [4, 6,7,8,9].

The NPR1 protein interacts with 7 of the 10 Arabidopsis TGAs [7, 8, 10]. These seven TGAs are further classified into three subclades, with clade I containing TGA1 and TGA4; clade 2 containing TGA2, TGA5, and TGA6; and clade III containing TGA3 and TGA7 [11]. In Arabidopsis, only TGA1 and TGA4 interact with NPR1 in SA-induced leaves, whereas the other TGAs constitutively interact with NPR1 [12]. Thus, all seven TGAs are the important components of the plant defense system.

In addition to their involvement in plant defenses, TGAs also act in plant development. For instance, when grown under low-nitrate conditions, tga1/tga4 shows an altered root architecture [13, 14]. TGA1 and TGA4 are also expressed around flower organ boundaries and are required for inflorescence architecture, meristem maintenance, and flowering [3].

In this study, we showed that TGA7 plays an important role in flowering time control. The loss of TGA7 function delayed flowering in Arabidopsis. To reveal the molecular mechanisms of TGA7 in flowering time control, the transcriptomic changes between WT and tga7 mutant seedlings at 9 days after germination (DAG) were analyzed by RNA-sEq. A total of 325 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified, and 4 DEGs were associated with flowering time pathways. These results provide insights into the genes potentially related to flowering time control in the tga7 mutant and will be useful for further studies on the molecular mechanisms of TGA7 in floral transition.

Methods

Plant materials

Arabidopsis plants were grown in soil under long-day (LD; 16-h/8-h, light/dark) or short-day (SD; 8-h/16-h, light/dark) conditions at 23 °C. Mutants gi-1, co-9, ft-10, svp-41, Col:FRISF2 (FRI-Col), fld-3, and fve-4 were all in the Columbia background [15, 16]. fpa-7 (SALK_138449), fca-2 (SALK_057540), flk-1 (SALK_007750), and tga7 (CS89835) seeds were bought from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (http://www.arabidopsis.org/).

Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequences (CAPS) analysis

A 689-bp DNA fragment of the tga7 mutant or wild-type (WT) was amplified using the following primers: Forward, 5′-TAAAGTTATCGCAGTTAGAGC-3′ and Reverse, 5′-CCGCATCAATCACAATG-3′. PCR was carried out for 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min. Then, the PCR products were digested by EcoRV and separated on 1 % agarose-TAE gels.

Plasmid construction and transgenic plant generation

To construct 35 S:TGA7, the TGA7 coding sequence was amplified and then cloned into the binary vector pCAMBIA1300-35 S. The primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Additional file 1. Transgenic plants were generated through Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation using the floral-dipping method. Transformants containing 35 S:TGA7 were selected on MS medium supplemented with hygromycin (30 mg L− 1).

Total RNA isolation

The isolation of total RNA was performed using an RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. DNase I was added to the mixture to eliminate genomic and plastid DNA.

mRNA library construction

Total RNA was analyzed using a NanoDrop and Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). To purify mRNA, oligo(dT) magnetic beads were used. Then, the mRNA was sheared into small fragments in the fragmentation buffer. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription using random hexamer primers, and the second-strand cDNA was synthesized by DNA polymerase. Afterwards, adapters were added to the double-stranded cDNA. To amplify the cDNA fragments, PCR was performed, and the resulting PCR products were purified and dissolved in elution buffer. Then, the PCR products were heat-denatured to produce the final library. The sequencing was performed on a BGIseq500 platform (BGI-Shenzhen, China). The transcriptome data sets have been submitted to the NCBI (accession number PRJNA649868).

De novo assembly and functional annotation of sequencing

The transcriptome data were filtered and analyzed in accordance with a previously published protocol with minor modifications [17]. A differential expression analysis was performed, and the significance levels of gene ontology (GO) terms were all determined, using Q value ≤ 0.05.

qRT-PCR

For the expression analysis, 1 µg RNA was used for reverse transcription. The cDNA was synthesized using a FastKing gDNA Dispelling RT SuperMix kit (TIANGEN) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was performed using the UltraSYBR Mixture (with ROX; CWBio, Beijing, China) and the CFX96 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). The expression levels of detected genes were normalized to TUB2 expression. Error bars denote standard deviations of three biological replicates [18]. The primers used for the expression analysis are listed in Additional file 1.

Results

Regulation of Arabidopsis flowering time by TGA7

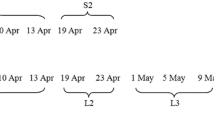

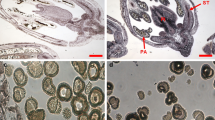

To reveal the function of TGA7 in controlling flowering time, we analyzed the TGA7 phenotype using a tga7 mutant that contained a point mutation in the seventh exon (Fig. 1a). The C to T mutation led to the loss of an EcoRV site in the TGA7 gene and resulted in an amino acid change from Ser to Leu in the TGA7 protein (Fig. 1a, b, Additional file 2). All the tga7 mutant plants had delayed flowering compared with wild-type (WT) seedlings under both LD and SD conditions (Fig. 1c–e), suggesting that TGA7 promotes flowering independently of the day length conditions. To determine whether the point mutation in the TGA7 gene is truly responsible for the observed phenotype, the mutants were backcrossed with the WT (Col-0). The F1 seedlings showed a WT phenotype (Additional file 3a, b), and F2 seedlings showed a segregation ratio of 3:1 (31:12, WT:tga7 phenotypes, χ2 = 0.19 < χ20.05 = 3.84; P > 0.05). We then analyzed all the 12 F2 seedlings having the tga7 mutant phenotype. These 12 F2 seedlings all displayed a homozygous point mutation in the TGA7 gene (Additional file 3c, d). We then transformed the tga7 mutant with a construct containing the coding sequence of TGA7 driven by the 35 S promoter. Two independent tga7 35 S:TGA7 transgenic lines exhibited flowering times comparable to those of WT plants (Fig. 1 g–i), indicating that TGA7 was responsible for the flowering phenotype of the tga7 mutant and that excess amounts of TGA7 do not further accelerate flowering.

TGA7 regulates flowering time in Arabidopsis. a The structure of the TGA7 coding region. Black boxes, gray boxes, and black lines represent exons, untranslated regions, and introns, respectively. The point mutation is shown underneath. Red arrowheads indicate the positions of primers used in b. b The cropped gels of the CAPS analysis of the wild-type and tga7 mutant. Genomic DNAs of the wild-type and tga7 mutant were amplified using the CAPS markers list in Additional file 1, and then, the PCR products were digested with EcoRV. ctga7 showed a delayed-flowering phenotype under LD conditions. Scale bar = 2 cm. d and e Flowering times of tga7 grown under LD (d) and SD (e) conditions. Values are from at least 10 plants showing specific genotypes. Asterisks indicate significant differences in flowering time between the WT and tga7 mutant (Student’s t test, p ≤ 0.05). f The expression level of TGA7 in various tissues of WT plants was analyzed by qRT-PCR (n = 3, ±standard deviations). JRL, juvenile rosette leaves; Rt, roots; ARL, adult rosette leaves; CL, cauline leaves; FL, flowers; St, inflorescence stems; Sil, siliques. gtga7 35 S:TGA7 exhibited a flowering time comparable to that of WT plants under LD conditions. Scale bar = 2 cm. h Flowering time of tga7 35 S:TGA7 grown under LD conditions. Values are representative of at least 15 plants showing specific genotypes. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the WT and tga7 mutant in flowering time (Student’s t test, p ≤ 0.05). i The TGA7 expression levels in independent TGA7-overexpression lines at 9 DAG. Error bars denote standard deviations

We then examined TGA7 expression in different tissues of WT plants by qRT-PCR and found that the highest TGA7 expression occurred in adult rosette leaves, whereas there was almost no expression of TGA7 in siliques (Fig. 1f).

Autonomous and thermosensory pathways regulate TGA7 expression

Because TGA7 is involved in floral transition, we examined which flowering genetic pathways may be involved in flowering time control. The expression of TGA7 remained steady in the photoperiod pathway mutants (Fig. 2a), and the phenotype of the tga7 mutant was delayed flowering under LD and SD conditions (Fig. 1c–e), suggesting that TGA7 may not be involved in the photoperiod pathway. In addition, there were almost no effects on TGA7 expression after a gibberellin treatment (Fig. 2b). In both WT and FRI-Col plants, a vernalization treatment did not alter TGA7 expression (Fig. 2c). These observations suggest that the gibberellin and vernalization pathways did not influence TGA7. By contrast, in the autonomous pathway mutants fca-2 and fve-4, the TGA7 expression level increased, whereas it decreased in fld-3and flk-1 (Fig. 2d), suggesting that the autonomous pathway may affect TGA7 expression.

TGA7 expression is regulated by several pathways. a TGA7 expression in photoperiod-pathway mutants at 9 DAG. b TGA7 expression after a gibberellin (GA) treatment. WT seedlings were grown under SD conditions for 2 weeks and then treated with 100 µM GA3 or 0.1 % ethanol weekly. Seedlings treated for 3 (W3) and 5 weeks (W5) were collected for further analyses. c TGA7 expression after a vernalization treatment. The seedlings were vernalized at 4 °C for 8 weeks. The 9-day-old seedlings were collected for further analyses. d TGA7 expression in autonomous-pathway mutants at 9 DAG. e The TGA7 expression level in WT seedlings grown at 16℃, 23℃, and 27℃ under LD conditions until 9 DAG. f TGA7 expression in WT, svp-41, and 35 S:SVP plants grown at 16 and 23 °C under LD conditions until 9 DAG. Asterisks indicate significant differences (Student’s t test, p ≤ 0.05). g Flowering times of wild-type, svp-41, and tga7 plants grown at 16 °C, 23 °C, and 27 °C under LD conditions. The ratios of flowering time between 16 and 23 °C (16 °C/23°C) and between 23 and 27 °C (23 °C/27°C) for all the genotypes are indicated in the attached table. Values were scored from at least 15 plants of each genotype. Error bars indicate standard deviations

The SVP gene plays crucial roles in the thermosensory pathway, and the svp-41 mutant displays a steady flowering phenotype under different temperature conditions [19]. We also analyzed TGA7 expression at different temperatures. The TGA7 expression increased along with the temperature (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, TGA7 expression was steady in WT, svp-41, and 35 S:SVP plants at 16℃, whereas TGA7 expression was higher in 35 S:SVP but lower in svp-41 at 23℃ (Fig. 2f). These findings demonstrate that the thermosensory pathway may also regulate TGA7 expression at ambient temperatures. In addition, tga7 flowered in a temperature-sensitive manner from 16 to 23 °C, but also flowered in a partial temperature-insensitive pattern from 23℃ to 27℃ (Fig. 2g). Thus, TGA7 may partially mediate the effect of the thermosensory pathway on flowering time.

Transcriptomes of WT and tga7 mutant seedlings

To understand how TGA7 affects flowering time, we identified genes downstream of TGA7 that might be involved in its role in promoting flowering. The RNA-seq analyses of WT and tga7 mutant seedlings were performed, and mRNAs were extracted, with three biological replicates, from WT and tga7 mutant seedlings at 9 DAG. In total, six RNA-seq libraries were constructed for transcriptome sequencing.

The raw data were qualified and filtered, yielding approximately 6.67 Gb of sequence data per library (Additional file 4). A Pair-wise Pearson’s correlation coefficients analysis of three replicates of each sample indicated that the sequencing data were highly repeatable (Fig. 3a). To gain an overview of the variations among the sequencing data, a principal components analysis (PCA) was performed, and the values of PC1 and PC2 were 97.58 and 2.21 %, respectively (Fig. 3b). The PCA clearly separated the six RNA-seq libraries into two groups, WT and tga7 mutant. The size distributions of the mRNAs are shown in Fig. 3c. The majority of mRNAs (84.55 %) were between 500 bp and 3,000 bp, and only 1.60 % of the mRNAs were > 5,000 bp.

Transcriptomes of WT and tga7 mutant seedlings. a Pair-wise Pearson’s correlation coefficients analysis showing that the sequencing data from three replicates of two samples are highly repeatable. b Principal components analysis of the transcriptomes. c The size distributions of mRNAs of the transcriptomes

Identification of DEGs between WT and tga7 mutant seedlings

The reads per kb per million reads values were calculated to determine the DEGs between WT and tga7 mutant seedlings at 9 DAG. In total, 325 DEGs were identified, of which 133 genes were induced and 192 genes were repressed (Fig. 4a). Among the 325 DEGs, AT3G55970, AT5G45570, AT5G44590, AT5G44440, and AT4G12480 were the most up-regulated genes, whereas AT3G01345, AT4G36700, AT3G56980, AT5G28520, and AT4G36700 were the most down-regulated genes. The heatmap in Fig. 4b shows the expression profiles of the DEGs between WT and tga7 mutant seedlings. A GO term enrichment analysis of these DEGs was performed and the top five most represented GO terms in biological process were “photosynthesis, light harvesting in photosystem I”, “photosynthesis, light harvesting”, “protein-chromophore linkage”, “photosynthesis”, and “photosynthesis, light harvesting in photosystem II”. In molecular function, they were “chlorophyll binding”, “protein domain specific binding”, “RNA polymerase II regulatory region sequence-specific DNA binding”, “hydrolase activity, acting on glycosyl bonds”, and “carbohydrate kinase activity”. In cellular component, the top five most represented GO terms were “photosystem I”, “photosystem II”, “plastoglobule”, “chloroplast thylakoid membrane”, and “chloroplast” (Fig. 4c).

Transcriptional profiles of WT and tga7 mutant seedlings at 9 DAG. a The numbers of genes that were up-regulated or down-regulated between WT and tga7 mutant seedlings at 9 DAG. b Expression profiles of the DEGs between WT and tga7 mutant seedlings at 9 DAG shown using a heatmap. c GO term enrichment analysis of the DEGs between WT and tga7 mutant seedlings

Identification of key flowering time-related DEGs

A large number of genes are flowering time-related and play vital roles in the floral transition, an important turning point from vegetative to reproductive growth [20,21,22]. Among the 325 DEGs identified between WT and tga7 mutant seedlings (Figs. 4), 4 DEGs were involved in flowering time pathways. The expression levels of FLC, MAF5, and SMZ were up-regulated, whereas that of NF-YC2 was down-regulated in tga7 mutant seedlings, compared with WT seedlings (Additional file 5).

Validation of the expression levels of flowering time-related DEGs

To validate the expression of the four flowering time-related DEGs (FLC, MAF5, SMZ, and NF-YC2) identified by RNA-seq (Additional file 5), three independent biological duplicates of WT and tga7 mutant seedlings collected at 9 DAG were analyzed by qRT-PCR. The expression levels and trends of the four flowering-related DEGs were consistent with the RNA-seq results (Fig. 5), which indicated that the RNA-seq data are reliable.

Quantitative real-time PCR validation of flowering time-related DEGs. Expression levels in all the panels were determined by qRT-PCR and then normalized to TUB2 expression. The data are from three independent replicates. Error bars denote significant differences. Asterisks indicate significant differences among samples (Student’s t test, p ≤ 0.05)

Discussion

In the present study, Arabidopsis that had lost TGA7 function showed a delayed-flowering phenotype (Fig. 1). To uncover the role of TGA7 in flowering time control, transcriptomic analyses between WT and tga7 mutant seedlings at the same developmental stage (9 DAG) revealed 325 DEGs, among which NF-YC2, SMZ, MAF5, and FLC were involved in flowering time pathways (Fig. 5; Additional file 5).

NF-Y, a heterotrimeric TF family, consists of three subfamilies, NF-YA, NF-YB, and NF-YC. NF-YB and NF-YC form dimers with a histone-folding domain, whereas NF-YA confers sequence specificity [23, 24]. The heterotrimeric NF-Y complex binds to promoters having CCAAT elements and then regulates the expression of target genes [23, 24]. Although each member of the NF-Y family in yeast and mammals is encoded by a single gene, they can be spliced into multiple isoforms post-translationally modified [25, 26]. In mammals, the NF-Y complex plays important roles in many processes, including endoplasmic reticulum stress, DNA damage, and cell cycle regulation [27,28,29]. However, in plants, every NF-Y is encoded by multiple genes and then forms sub-families [30]. There are 10 NF-YA, 13 NF-YB, and 13 NF-YC genes in the Arabidopsis genome [31]. As with other plant TFs, duplicate members in the NF-Y family also have similar functions in Arabidopsis [30, 32]. The NF-Y complex plays crucial roles in plant stress responses, as well as growth and development [26, 30, 33].

NF-Y genes, including NF-YB2, NF-YB3, NF-YC3, NF-YC4, and NF-YC9, are involved in the photoperiod pathway of Arabidopsis, [34,35,36,37]. The single nf-y mutant did not show any obvious flowering phenotype, whereas double or triple mutants, such as nf-yb2-1 nf-yb3-1 or nf-yc3-2 nf-yc4-1 nf-yc9-1, respectively, delayed flowering [37]. Because NF-YC2 is in the same subfamily as NF-YC3, NF-YC4, and NF-YC9, they may possess similar functions in the photoperiod-dependent control of flowering-time. However, tga7 exhibited a delayed-flowering phenotype under both LD and SD conditions (Fig. 1c–e), suggesting that the later flowering in tga7 was independent of the photoperiod pathway. Thus, the decreased expression of NF-YC2 may not result in the delayed-flowering seen in tga7 mutant plants.

SCHLAFMÜTZE (SMZ), together with its paralog SCHNARCHZAPFEN (SNZ), belongs to the AP2-type TF family that represses flowering. Both SMZ and SNZ are targets of miR172, an important regulator in the ageing pathway [38]. SMZ delays flowering under LD conditions. When expressed in leaves, SMZ represses flowering by directly binding to the FT genomic locus, down-regulating FT expression [38, 39]. Thus, the elevated SMZ expression level may at least partially account for the delayed flowering of the tga7 mutant.

Furthermore, the FLC and MAF5 expression levels were increased in the tga7 mutant compared with the WT. FLC, encoding an MADS-box protein, is a critical repressor in the flowering regulatory network [40,41,42]. MAF1–5 are five FLC homologs in Arabidopsis, and FLC and MAF1–5 are MADS-box TFs that repress floral transition [43]. Many flowering regulatory genes in the autonomous pathway promote flowering by directly repressing FLC expression, and the mutants of these genes, including FLD and FLK in the autonomous pathway, result in the delayed-flowering phenotype under both LD and SD conditions [44,45,46].

FLD encodes a histone demethylase in Arabidopsis and is a homolog of the human LSD1 (histone H3K4 demethylase) [47, 48]. It represses FLC expression through histone modifications [47,48,49,50]. FLD physically interacts with FPA and FCA, two autonomous pathway genes [50]. The roles of FCA and FPA on regulating FLC expression and floral transition may depend on FLD [50, 51]. Moreover, FLD also interacts with HDA5 and HDA6, two histone deacetylases, to regulate FLC expression. FLK contains RNA-binding domains and only exists in plants [52, 53]. FLK may repress the FLC expression level by binding FLC RNAs [54, 55]. However, how FLD and FLK regulate FLC expression needs further investigation. Here, we found that TGA7 expression decreased in fld-3 and flk-1 mutant lines (Fig. 2d). Because the expression levels of FLC and MAF5, the closest homolog of FLC, increased dramatically in tga7 compared with WT seedlings (Additional file 5, Fig. 5), and because the tga7 mutant displayed a delayed-flowering phenotype under both LD and SD conditions (Fig. 1c, d, e), we propose that FLD and FLK regulate FLC expression through TGA7.

Conclusions

In summary, six cDNA libraries from WT and tga7 mutant Arabidopsis seedlings at 9 DAG were constructed independently for sequencing. Through bioinformatics mining, 325 DEGs were identified, and 4 genes, NF-YC2, SMZ, MAF5, and FLC, were associated with flowering time control. The differential expression levels of these flowering time-related genes were analyzed and validated by qRT-PCR. Among them, FLC and MAF5 may be mainly responsible for the delayed-flowering phenotype in tga7, because TGA7 expression was regulated by autonomous pathway genes. Further studies should elucidate how TGA7 effects FLD and FLK in regulating FLC expression and deepen our knowledge of the autonomous pathway’s role in controlling flowering.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the NCBI Short Read Archive with accession number PRJNA649868.

Abbreviations

- CAPS:

-

Cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences

- DAG:

-

Days after germination

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- GA:

-

Gibberellin

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- LD:

-

Long-day

- NPR1:

-

Non-repressor of pathogenesis-related gene 1

- PCA:

-

Principal components analysis

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time PCR

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA sequencing

- SD:

-

Short-day

- SMZ:

-

SCHLAFMÜTZE

- SNZ:

-

SCHNARCHZAPFEN

- TF:

-

Transcription factor

- TGA:

-

TGACG-binding transcription factor

- WT:

-

Wild-type

References

Gatz C. From pioneers to team players: TGA transcription factors provide a molecular link between different stress pathways. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2013;26(2):151–9.

Noshi M, Mori D, Tanabe N, Maruta T, Shigeoka S. Arabidopsis clade IV TGA transcription factors, TGA10 and TGA9, are involved in ROS-mediated responses to bacterial PAMP flg22. Plant Sci. 2016;252:12–21.

Wang Y, Salasini BC, Khan M, Devi B, Bush M, Subramaniam R, Hepworth SR. Clade I TGACG-Motif Binding Basic Leucine Zipper Transcription Factors Mediate BLADE-ON-PETIOLE-Dependent Regulation of Development. Plant Physiol. 2019;180(2):937–51.

Zhang Y, Fan W, Kinkema M, Li X, Dong X. Interaction of NPR1 with basic leucine zipper protein transcription factors that bind sequences required for salicylic acid induction of the PR-1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(11):6523–8.

Johnson C, Boden E, Arias J. Salicylic acid and NPR1 induce the recruitment of trans-activating TGA factors to a defense gene promoter in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2003;15(8):1846–58.

Gutsche N, Zachgo S. The N-Terminus of the Floral Arabidopsis TGA Transcription Factor PERIANTHIA Mediates Redox-Sensitive DNA-Binding. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153810.

Despres C, DeLong C, Glaze S, Liu E, Fobert PR. The Arabidopsis NPR1/NIM1 protein enhances the DNA binding activity of a subgroup of the TGA family of bZIP transcription factors. Plant Cell. 2000;12(2):279–90.

Zhou JM, Trifa Y, Silva H, Pontier D, Lam E, Shah J, Klessig DF. NPR1 differentially interacts with members of the TGA/OBF family of transcription factors that bind an element of the PR-1 gene required for induction by salicylic acid. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000;13(2):191–202.

Shearer HL, Cheng YT, Wang L, Liu J, Boyle P, Despres C, Zhang Y, Li X, Fobert PR. Arabidopsis clade I TGA transcription factors regulate plant defenses in an NPR1-independent fashion. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2012;25(11):1459–68.

Jakoby M, Weisshaar B, Droge-Laser W, Vicente-Carbajosa J, Tiedemann J, Kroj T, Parcy F. bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7(3):106–11.

Xiang C, Miao Z, Lam E. DNA-binding properties, genomic organization and expression pattern of TGA6, a new member of the TGA family of bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;34(3):403–15.

Kesarwani M, Yoo J, Dong X. Genetic interactions of TGA transcription factors in the regulation of pathogenesis-related genes and disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;144(1):336–46.

Alvarez JM, Riveras E, Vidal EA, Gras DE, Contreras-Lopez O, Tamayo KP, Aceituno F, Gomez I, Ruffel S, Lejay L, et al. Systems approach identifies TGA1 and TGA4 transcription factors as important regulatory components of the nitrate response of Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Plant J. 2014;80(1):1–13.

Canales J, Contreras-Lopez O, Alvarez JM, Gutierrez RA. Nitrate induction of root hair density is mediated by TGA1/TGA4 and CPC transcription factors in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2017;92(2):305–16.

Gong X, Shen L, Peng YZ, Gan Y, Yu H. DNA Topoisomerase Ialpha Affects the Floral Transition. Plant Physiol. 2017;173(1):642–54.

Liu L, Li C, Teo ZWN, Zhang B, Yu H. The MCTP-SNARE Complex Regulates Florigen Transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2019;31(10):2475–90.

Wang J, Xue Z, Lin J, Wang Y, Ying H, Lv Q, Hua C, Wang M, Chen S, Zhou B. Proline improves cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction and attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis via redox regulation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;178:114065.

Qin C, Cheng L, Zhang H, He M, Shen J, Zhang Y, Wu P. OsGatB, the Subunit of tRNA-Dependent Amidotransferase, Is Required for Primary Root Development in Rice. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:599.

Wigge PA. Ambient temperature signalling in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2013;16(5):661–6.

Song YH, Ito S, Imaizumi T. Flowering time regulation: photoperiod- and temperature-sensing in leaves. Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18(10):575–83.

Shim JS, Kubota A, Imaizumi T. Circadian Clock and Photoperiodic Flowering in Arabidopsis: CONSTANS Is a Hub for Signal Integration. Plant Physiol. 2017;173(1):5–15.

Kinoshita A, Richter R. Genetic and molecular basis of floral induction in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(9):2490–504.

Huber EM, Scharf DH, Hortschansky P, Groll M, Brakhage AA. DNA minor groove sensing and widening by the CCAAT-binding complex. Structure. 2012;20(10):1757–68.

Nardini M, Gnesutta N, Donati G, Gatta R, Forni C, Fossati A, Vonrhein C, Moras D, Romier C, Bolognesi M, et al. Sequence-specific transcription factor NF-Y displays histone-like DNA binding and H2B-like ubiquitination. Cell. 2013;152(1–2):132–43.

Li XY, Hooft van Huijsduijnen R, Mantovani R, Benoist C, Mathis D. Intron-exon organization of the NF-Y genes. Tissue-specific splicing modifies an activation domain. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(13):8984–90.

Mantovani R. The molecular biology of the CCAAT-binding factor NF-Y. Gene. 1999;239(1):15–27.

Oldfield AJ, Yang P, Conway AE, Cinghu S, Freudenberg JM, Yellaboina S, Jothi R. Histone-fold domain protein NF-Y promotes chromatin accessibility for cell type-specific master transcription factors. Mol Cell. 2014;55(5):708–22.

Benatti P, Chiaramonte ML, Lorenzo M, Hartley JA, Hochhauser D, Gnesutta N, Mantovani R, Imbriano C, Dolfini D. NF-Y activates genes of metabolic pathways altered in cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7(2):1633–50.

Dolfini D, Zambelli F, Pedrazzoli M, Mantovani R, Pavesi G. A high definition look at the NF-Y regulome reveals genome-wide associations with selected transcription factors. Nucl Acids Res. 2016;44(10):4684–702.

Petroni K, Kumimoto RW, Gnesutta N, Calvenzani V, Fornari M, Tonelli C, Holt BF 3rd, Mantovani R. The promiscuous life of plant NUCLEAR FACTOR Y transcription factors. Plant Cell. 2012;24(12):4777–92.

Siefers N, Dang KK, Kumimoto RW, Bynum WEt, Tayrose G, Holt BF 3rd. Tissue-specific expression patterns of Arabidopsis NF-Y transcription factors suggest potential for extensive combinatorial complexity. Plant Physiol. 2009;149(2):625–41.

Laloum T, De Mita S, Gamas P, Baudin M, Niebel A. CCAAT-box binding transcription factors in plants: Y so many? Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18(3):157–66.

Gusmaroli G, Tonelli C, Mantovani R. Regulation of novel members of the Arabidopsis thaliana CCAAT-binding nuclear factor Y subunits. Gene. 2002;283(1–2):41–8.

Wenkel S, Turck F, Singer K, Gissot L, Le Gourrierec J, Samach A, Coupland G. CONSTANS and the CCAAT box binding complex share a functionally important domain and interact to regulate flowering of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18(11):2971–84.

Kumimoto RW, Zhang Y, Siefers N, Holt BF 3. NF-YC3, NF-YC4 and NF-YC9 are required for CONSTANS-mediated, photoperiod-dependent flowering in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2010;63(3):379–91. rd. .

Cao S, Kumimoto RW, Gnesutta N, Calogero AM, Mantovani R, Holt BF 3. A Distal CCAAT/NUCLEAR FACTOR Y Complex Promotes Chromatin Looping at the FLOWERING LOCUS T Promoter and Regulates the Timing of Flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2014;26(3):1009–17. rd. .

Hou X, Zhou J, Liu C, Liu L, Shen L, Yu H. Nuclear factor Y-mediated H3K27me3 demethylation of the SOC1 locus orchestrates flowering responses of Arabidopsis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4601.

Mathieu J, Yant LJ, Murdter F, Kuttner F, Schmid M. Repression of flowering by the miR172 target SMZ. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(7):e1000148.

Gras DE, Vidal EA, Undurraga SF, Riveras E, Moreno S, Dominguez-Figueroa J, Alabadi D, Blazquez MA, Medina J, Gutierrez RA. SMZ/SNZ and gibberellin signaling are required for nitrate-elicited delay of flowering time in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(3):619–31.

He Y. Control of the transition to flowering by chromatin modifications. Mol Plant. 2009;2(4):554–64.

Rataj K, Simpson GG. Message ends: RNA 3’ processing and flowering time control. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(2):353–63.

Mahrez W, Shin J, Munoz-Viana R, Figueiredo DD, Trejo-Arellano MS, Exner V, Siretskiy A, Gruissem W, Kohler C, Hennig L. BRR2a Affects Flowering Time via FLC Splicing. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(4):e1005924.

Parenicova L, de Folter S, Kieffer M, Horner DS, Favalli C, Busscher J, Cook HE, Ingram RM, Kater MM, Davies B, et al. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the complete MADS-box transcription factor family in Arabidopsis: new openings to the MADS world. Plant Cell. 2003;15(7):1538–51.

Michaels SD. Flowering time regulation produces much fruit. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12(1):75–80.

Yu X, Michaels SD. The Arabidopsis Paf1c complex component CDC73 participates in the modification of FLOWERING LOCUS C chromatin. Plant Physiol. 2010;153(3):1074–84.

He Y. Chromatin regulation of flowering. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17(9):556–62.

Yu CW, Liu X, Luo M, Chen C, Lin X, Tian G, Lu Q, Cui Y, Wu K. HISTONE DEACETYLASE6 interacts with FLOWERING LOCUS D and regulates flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011;156(1):173–84.

Jiang D, Yang W, He Y, Amasino RM. Arabidopsis relatives of the human lysine-specific Demethylase1 repress the expression of FWA and FLOWERING LOCUS C and thus promote the floral transition. Plant Cell. 2007;19(10):2975–87.

He Y, Michaels SD, Amasino RM. Regulation of flowering time by histone acetylation in Arabidopsis. Science. 2003;302(5651):1751–4.

Liu F, Quesada V, Crevillen P, Baurle I, Swiezewski S, Dean C. The Arabidopsis RNA-binding protein FCA requires a lysine-specific demethylase 1 homolog to downregulate FLC. Mol Cell. 2007;28(3):398–407.

Baurle I, Dean C. Differential interactions of the autonomous pathway RRM proteins and chromatin regulators in the silencing of Arabidopsis targets. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2733.

Mockler TC, Yu X, Shalitin D, Parikh D, Michael TP, Liou J, Huang J, Smith Z, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, et al. Regulation of flowering time in Arabidopsis by K homology domain proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(34):12759–64.

Lim MH, Kim J, Kim YS, Chung KS, Seo YH, Lee I, Hong CB, Kim HJ, Park CM. A new Arabidopsis gene, FLK, encodes an RNA binding protein with K homology motifs and regulates flowering time via FLOWERING LOCUS C. Plant Cell. 2004;16(3):731–40.

Veley KM, Michaels SD. Functional redundancy and new roles for genes of the autonomous floral-promotion pathway. Plant Physiol. 2008;147(2):682–95.

Cheng JZ, Zhou YP, Lv TX, Xie CP, Tian CE. Research progress on the autonomous flowering time pathway in Arabidopsis. Physiol Mol Biol Pla. 2017;23(3):477–85.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to BGI (Shenzhen, China) for technical support and Prof. Yiguo Hong for reading this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31770344 and 31970328). The funding body played no role in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CQ and NNS designed the experiments. XRX, JYX, CY, QQC and PCZ performed the experiments, XRX and CY carried out the qRT-PCR analysis. CQ, YKH and QGL analyzed the data. CQ drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

The primers used in this study.

Additional file 2.

Alignment of WT and mutant TGA7 protein sequences.

Additional file 3.

a The phenotypes of F1 seedlings grown under long-day conditions. Scale bar = 2 cm. b The cropped gels of the CAPS analysis of wild-type, tga7 mutant, and F1seedlings. Genomic DNAs of wild-type, tga7 mutant, and F1seedlings were amplified using the CAPS markers listed in Additional file 1, and then, the PCR products were digested with EcoRV. c The tga7 phenotype of F2 seedlings under long-day conditions. Scale bar = 2 cm. d The cropped gels of the CAPS analysis of wild-type, tga7 mutant, and 12 F2seedlings showing the tga7 phenotype. Genomic DNAs of wild-type, tga7 mutant, and F2seedlings were amplified using the CAPS markers listed in Additional file 1, and then, the PCR products were digested with EcoRV.

Additional file 4.

The detailed information of raw reads from different samples.

Additional file 5.

Identification of key flowering time-related DEGs.

Additional file 6.

The original, full-length gel that is displayed in Fig. 1b.

Additional file 7.

The original, full-length gel that is displayed in Additional file 3b.

Additional file 8.

The original, full-length gel that is displayed in Additional file 3d.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, X., Xu, J., Yuan, C. et al. Characterization of genes associated with TGA7 during the floral transition. BMC Plant Biol 21, 367 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-03144-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-03144-w