Abstract

Background

The atmospheric CO2 concentration is rising continuously, and abnormal precipitation may occur more frequently in the future. Although the effects of elevated CO2 and drought on plants have been well reported individually, little is known about their interaction, particularly over a water status gradient. Here, we aimed to characterize the effects of elevated CO2 and a water status gradient on the growth, photosynthetic capacity, and mesophyll cell ultrastructure of a dominant grass from a degraded grassland.

Results

Elevated CO2 stimulated plant biomass to a greater extent under moderate changes in water status than under either extreme drought or over-watering conditions. Photosynthetic capacity and stomatal conductance were also enhanced by elevated CO2 under moderate drought, but inhibited with over-watering. Severe drought distorted mesophyll cell organelles, but CO2 enrichment partly alleviated this effect. Intrinsic water use efficiency (WUEi) and total biomass water use efficiency (WUEt) were increased by elevated CO2, regardless of water status. Plant structural traits were also found to be tightly associated with photosynthetic potentials.

Conclusion

The results indicated that CO2 enrichment alleviated severe and moderate drought stress, and highlighted that CO2 fertilization’s dependency on water status should be considered when projecting key species’ responses to climate change in dry ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

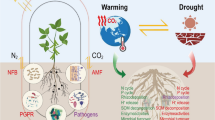

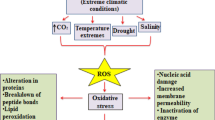

The IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) showed that atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration had increased by 40 % since the pre-industrial era, reaching ~390 μmol mol−1 in 2011. It is predicted to rise to 500 μmol mol−1, perhaps even above 900 μmol mol−1, by the end of this century. Continued emissions of greenhouse gases will cause further warming and precipitation changes [1]. The effects of elevated CO2 concentration (elevated CO2) and climatic change on plants—from the molecular basis to physiological processes, individual growth, and vegetation productivity aspects—have attracted considerable attention for several decades (e.g., [2–6]).

Many studies have reported the biological responses of plants to CO2 enrichment and its interactions with other environmental factors (e.g., [3, 4, 6]). The effects of elevated CO2 include enhanced net photosynthesis rate (A net), down-regulated stomatal conductance (g s) [3, 7–9], dilution of chemical elements [10], imbalance of sink–source relationships [11, 12], increased plant growth and vegetation productivity [2, 13], changes in species competition interactions and community structure [13–15], and lengthened growing seasons [16]. However, these elevated CO2-induced changes might be mediated by other environmental factors, particularly changes of water availabilities. Severe drought adversely affects plant growth, gas exchange, and photosynthetic activity [17], but elevated CO2 might partly alleviate the harmful impact of water deficit stress on these biological processes, and even survival [18–21]. Elevated CO2 can enhance plant resistance to water deficit stress by mitigating oxidative damage, maintaining A net and decreasing g s, and improving the plant water status, thereby raising the water use efficiency (WUE) [4, 21–24]. Under moderate water stress, a marked stimulation occurs due to elevated CO2 [22–26]. However, over-watering can reduce, or even reverse this stimulation [27–30]. Nevertheless, few studies on the combined effects of elevated CO2 and a water status gradient have been conducted, particularly on multiple scales.

Agropyron cristatum (L.) Gaertn, or crested wheatgrass, a C3 species, is a dominant species in the steppe regions of Central Asia, and is also widespread in western North America [31, 32]. It is a perennial herb native to North China with good palatability and high forage value. Moreover, its prosperity is recognized as an indicator of degradation of the steppe ecosystem in the context of overgrazing and adverse climate change. For instance, degradation might initially occur if crested wheatgrass thrives relative to other dominant species such as Leymus chinensis and Stipa grandis [33]. Thus, this species is crucial for assessing the vulnerability and restorative capacity of the semiarid region, as well as forage resource management. These temperate grasslands, which are dominated by several major grasses including A. cristatum, have been severely degraded during recent decades because of adverse climatic change and improper land use [34–37]. Although this arid region is projected to become drier and hotter, excessive precipitation events may occur more frequently [38, 39]. This would further threaten the ecosystem function including dominant species growth and survival [36, 37, 40]. The leaf-level instantaneous responses of A net, g s, and WUE to elevated CO2 have been quite well investigated [4, 6, 8]. To our knowledge, however, few prior efforts have been made to examine the effects of elevated CO2 under a wide-ranging water status gradient (seven watering treatments from extremely severe deficit to relative over-watering) (but see Manea and Leishman, [15]), particularly integrating multiple variables from organelle structure to physiological processes, individual morphology and structure, biomass allocation, and plant growth aspects. In this experiment, structural and physiological traits were examined to find sensitive indicators, and to summarize the adaptive strategy of A. cristatum to climatic changes. The objective of the current study was to test the hypotheses: (1) elevated CO2 modifies the effects of soil water status on the dominant species, with stimulation in a moderate range of water status changes, no positive response with over-watering, but an alleviation of damage from severe water deficit; and (2) associated responses co-occur at the mesophyll cell ultrastructure, photosynthetic physiological activity, plant growth and structure levels under elevated CO2 and different water conditions.

Methods

Plant culture

Each PVC plastic pot (9.7 cm in diameter, 9.5 cm in height, 0.70 L) was filled with 0.68 ± 0.01 (±SE, n = 60) kg of dry soil, and planted with four plants per pot. The soil was retrieved from the local soil surface (0–30 cm), and A. cristatum seeds were collected the year before the experiment from the local steppe—a typical grassland ecosystem in Xilinhot (43°38′N, 116°42′E, 1100 m a.s.l.), Inner Mongolia, China. The soil was a castanozem type, with a medium texture containing 29.0 %, 31.2 %, and 39.8 % clay (<5 μm particle diameter), silt (5–50 μm), and sand (>50 μm), respectively. The soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, and available nitrogen concentrations were 12.31 ± 0.19 g kg−1, 1.45 ± 0.02 g kg−1, and 81.61 ± 0.71 mg kg−1, respectively. The soil water field capacity (FC) and permanent wilting point were 25.8 and 6.0 % (w/w), respectively, and the gravimetric bulk density was 1.21 g cm−3. With a mean annual temperature of 2.95 °C and mean annual precipitation (MAP) of 266 mm over the past 30 years, this region is characterized by a continental temperate climate with a dry, frigid winter (−18.6 °C lowest mean month temperature in Jan), and a wet, hot summer (21.4 °C maximal mean month temperature in Jul). Most precipitation (88 %) occurs in the growth season from May to Sep. To obtain uniform seedlings [26, 41], all pots were initially placed in a naturally illuminated glasshouse (day/night temperatures of 26–28/18–20 °C) until the third leaf emerged (27 days after sowing), and then transferred into two open-top chambers (OTCs) to subject the plants to two-month watering and increased CO2 concentration treatments. Water was provided by a sprayer at around 17:00 every 3 days according to previous similar experiments [26, 35].

The OTCs were established in a regular hexahedron shape (each side 85 cm wide, 150 cm high) with a top-opening rain shelter on the top and a space below for free exchange of gases between the OTC and ambient atmosphere. Pure CO2 gas (99.999 %) was supplied from a cylinder (Chao Hong Ping Gas Co. Ltd, Beijing, China), and a CO2 gas sensor (eSENSE-D, SenseAir, Delsbo, Sweden) was used to continuously monitor and control the CO2 concentration over 24 h with a data logger (DAM-3058RTU, Altai Sci Tech Dev Co. Ltd., Shang Hai, China). The CO2 concentrations had a ±30 μmol mol−1 change relative to the set points. The air temperature and relative humidity (RH) were monitored using thermocouples (HOBO S-TMB-M006, Onset Computer Co., Bourne, MA, USA) and humidity transducers (HOBO S-SMA-M005) installed at 75 cm height in and out of the chambers, respectively. Climatic data were automatically recorded and collected by a logger (HOBO H21-002) every 30 min during the experiments; day/night temperatures were 28.3 ± 5.7/22.7 ± 4.2 °C and RH was 62.4 ± 4.0 % in the OTCs, which were 1.3/0.5 °C greater and 3.5 ± 2.3 % lower than outside the OTCs. The OTC system has been proven to have acceptable effectiveness, relative availability, and data comparability for assessing the effects of elevated CO2 with climatic change at low cost [42, 43], although data interpretation needs to be cautious in various environmental contexts [44, 45].

Experimental design

The experiment was designed with two factors, two CO2 concentrations (ambient CO2, ~390; elevated CO2, 550 μmol mol−1) and a seven-level precipitation gradient: W−60 (−60 % relative to mean precipitation in the local site over 30 years, as an extreme drought treatment), W−30 (−30 % relative to local mean precipitation), W−15 (−15 % relative to local mean precipitation), W0 (local mean precipitation, the control watering treatment), W15 (+15 % relative to local mean precipitation), W30 (+30 % relative to local mean precipitation, an over-watering treatment relative to the normal local precipitation), and W60 (+60 % relative to local mean precipitation), roughly equaling 147.0, 257.3, 312.5, 367.6, 422.7, 477.9, and 588.1 mm of precipitation during the growth season, respectively. Two OTCs were used, with separate irrigation treatments within each one as a split plot and 3–5 replicates (pots/treatment). A total of 80 plots were included initially; some pots were kept in reserve in case of experimental or plant growth problems. Plants were randomly placed within each OTC initially, replaced every 3 days, and transferred between the two chambers weekly (CO2 target points were switched simultaneously) to minimize any differences between growth chambers except for the desired treatments—CO2 concentration and water status [26, 46, 47].

Soil water status and water use

The soil water content (SWC, g water g−1 dry soil) during the experiment was determined by weighing pots. The soil dry weight (SDW) at sowing was calculated as (TW − PW) × (1- SWC0) at sowing (the SWC0 was determined before sowing by oven-drying soil samples; there was no water drainage because the pots used had no holes, and plant weight was neglected). The SWC during the experiment was expressed as (TW − SDW − PW)/SDW, and the soil relative water content (SRWC) was expressed as SWC/FC × 100. Water use, i.e., actual evapotranspiration during the entire experiment, was derived from a water balance equation; water use = TW at harvest − TW at initial time + applied water amount. Thus, total biomass water use efficiency (WUEt) could be estimated as total plant biomass/water use [48]. TW is the total weight of the pot plus soil at each measurement time; PW is the net pot weight determined before filling with soil; FC is the SWC measured 24 h after fully wetting the soil.

Plant biomass and leaf area

Each plant was separated into four parts, the stem, root, green leaves, and dead leaves, at both the start and end of the experiment, dried at 75 °C to a constant weight, and then weighed to get the biomass. Before drying, plant height, tiller and green leaf numbers were recorded; and green leaf area per plant, and the leaf parts used to determine gas exchange parameters were measured with a WinFOLIA system for root/leaf analysis (WinRhizo, Régent Instruments, Quebec, Canada).

Plant growth analysis

Plant growth analysis was performed following Poorter [49]. The relative growth rate of each individual (RGR, mg g−1 day−1) was expressed as (ln w 2 − ln w 1)/(t 2 − t 1), where w 2 and w 1 are the biomass at final and initial harvest dates, respectively, and t 2 and t 1 indicate the two harvest times. The leaf mass ratio of total plant mass (LMR), stem mass ratio (SMR), and root mass ratio (RMR), as biomass allocation indicators, were expressed as percentages of leaf, stem, and root mass in the total plant mass, respectively. The plant/leaf morphological and structural indicators leaf area ratio (LAR, m2 kg−1; an indicator of the canopy size), leaf area and root mass ratio (LARMR, m2 kg−1; a proxy of the biomass balance between light-intercepting organs and resource element uptake organs), specific stem length (SSL, cm mg−1; a marker of the investment of stem carbon into plant height), and specific leaf area (SLA, m2 kg−1; an indicator of leaf thickness and compactness) were expressed as ratios of leaf area to whole plant mass, leaf area to root mass, stem length to mass, and leaf area to mass, respectively [49].

Photosynthesis and chlorophyll a fluorescence

Leaf gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence were measured simultaneously using an open gas exchange system (LI-6400 F, LI-COR, Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) combined with a leaf chamber fluorometer (LI-6400-40, LI-COR). Illumination was supplied to the leaves from a red-blue LED light source and the data were initially analyzed with data acquisition software (OPEN 6.1.4, LI-COR). Before measurement, the leaves were acclimated in the chamber for at least 10 min at 26–28 °C with a CO2 concentration of 390 μmol mol−1 and a photosynthetic photon flux density of 1500 μmol m−2 s−1, under which photosynthesis is nearly saturated, to obtain gas exchange parameters such as net light-saturated maximum photosynthetic rate (A sat), g s, transpiration rate (E), and intrinsic water use efficiency (WUEi, A sat/E). We measured at least three each of the youngest and fully expanded leaves from different individuals (one plant per pot) for all replicates, from 9:00 to 16:30 h daily. The vapor pressure deficit (VPD) in the cuvette was maintained at 1.7–2.7 kPa (2.39 ± 0.04, n = 492), possibly reflecting the actual conditions within the OTCs [26, 50]. The steady-state value of fluorescence (F s) was determined, and a second saturating pulse at 8000 μmol m−2 s−1 was imposed to determine the maximal light-adapted fluorescence (F' m). The actinic light was removed and the minimal fluorescence in the light-adapted state (F' 0) was determined after 3 s of far-red illumination. The maximum photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (F v/F m) was determined midnight–predawn in completely dark-adapted leaves with a leaf fluorometer (LI-6400-40) linked to a LI-6400 F gas exchange system. The minimal fluorescence yield (F 0) was determined under low modulated light of 1.0 μmol m−2 s−1, and the maximal fluorescence yield (F m) was obtained with a 0.8 s saturating pulse at ~8000 μmol m−2 s−1. The fluorescence parameters were calculated from the following formulae [51, 52]; the maximal efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) photochemistry is F v/F m = (F m − F 0)/F m, and the efficiency of excitation energy captured by open PSII reaction centers is F' v/F' m = (F' m − F' 0)/F' m.

Estimation of A/C i response curves

To analyze the A/C i response curve to obtain key photosynthetic capacity parameters, a stepwise CO2 concentration gradient was implemented (390, 300, 200, 100, 50, 390, 390, 550, 800, and 1000 μmol m−2 s−1). Note, the third 390 value is not an error, but a trick to easily recover the ambient CO2 level from the lowest point of 50 μmol m−2 s−1. At each CO2 level, the leaves needed 2–3 min to equilibrate, and a match was also run to balance the CO2 and water vapor concentrations between the reference and leaf chambers. Furthermore, to estimate maximum rate of carboxylation (V c,max), maximum rate of electron transport (J max), and rate of thiose phosphate utilization (TPU), a curve-fitting software tool by Sharkey et al. [53] based on the method of Farquhar et al. [54] was run to analyze the A/C i response data.

Electron microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy, 2-mm2 pieces from the middle sections of the youngest and fully expanded leaves were dissected and immediately fixed in 2.5 % (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) overnight at 4 °C. The samples were then washed three times with the same buffer and post-fixed in 1 % osmium tetroxide overnight at 4 °C. After being washed in the same buffer, the leaf tissues were passed through an ethanol dehydration series, and then infiltrated and embedded in Spurr’s resin (Agar Scientific, Essex, UK). Sections were cut using an Ultracut R ultramicrotome (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The thin sections were stained with 2 % uranyl acetate and lead citrate [55], and then observed and photographed under a transmission electron microscope (JEM-1230, JEOL Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). For each treatment, three leaf samples were examined, and approximately 130 mesophyll cells were randomly chosen for the observations.

Statistical analyses

A principal component analysis (PCA) was first conducted to test the relationships among the traits including the plant growth, structural, morphological, biomass allocation, and photosynthetic parameters, and the multivariate patterns of the effects of CO2 concentration and watering treatments alone and in combination [26, 56, 57]. Thereafter, we conducted an analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the plant growth, structural, morphological, biomass allocation, and photosynthetic traits, and the anatomical changes in mesophyll cells and their organelles with GLM Full Factorial Mode to test the main effects of watering, elevated CO2, and their interactions. Where watering treatments had a significant effect based on ANOVA, a multiple comparison was done with Duncan’s multiple range test. A one-way ANOVA was also conducted to test the differences between the two CO2 levels within the same watering treatment. The multiple factorial ANOVA model can be used for unequal variances and data near a normal distribution. All statistical analyses were made using the SPSS 20.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Unless otherwise noted, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Soil water status

The watering treatments produced a wide-ranging soil water gradient combined with either ambient or elevated CO2 during the entire experimental period; when measured before watering at 17:00 every 3 days (the irrigation day) during a consecutive 10-day period, the SRWCs were 26.7 %, 39.4 %, 42.7 %, 45.6 %, 50.8 %, 53.3 %, and 61.7 % in the W−60, W−30, W−15, W0, W+15, W+30, W+60 watering treatments at ambient CO2, and 25.4 %, 36.1 %, 38.4 %, 44.0 %, 45.5 %, 50.9 %, and 51.5 % at elevated CO2, respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S1), indicating that elevated CO2 reduced the SRWC under every watering treatment (on average from 45.7 to 41.7 %, decreasing by 8.9 %). Watering and elevated CO2 exerted significant effects almost every day over the continuous 10-day period except for elevated CO2 concentration on the 57th and 62nd days after sowing according to a GLM ANOVA (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Multiple plant traits and environmental effects

PCA on multiple traits showed that the first and second principal components (PCs) explained 43.9 % and 15.2 % of the total variance, respectively (Fig. 1a). Most of the traits related to plant growth and photosynthetic activities were closely and positively correlated with PC1, and their loadings were mostly located in quadrant I. Those related to canopy size had similar correlations with PC1, and were mostly located in quadrant IV. Root and shoot biomass allocation traits were closely correlated with PC2, but separated conversely in quadrants II and IV, respectively. Projections for the multivariate traits and the effects of the two factors showed a complex pattern (Fig. 1b). However, the projections with extreme water deficit, including W−60 with ambient CO2 (NW−60) and W−60 with elevated CO2 (EW−60), and severe water deficit (NW−30, and EW−30) showed a distinct pattern, mostly appearing in the left part relative to the vertical line of origin, being opposed to those under relatively ample water conditions.

Principal component analysis on plant functional traits of Agropyron cristatum under elevated CO2 with water status gradient. The first two principal components (PCs) were shown (a), and projections of the two PCs were sorted by the combined treatments (b). A sat, light-saturated maximum photosynthetic rate; C i, intercellular CO2 concentration; E, transpiration rate; g s, stomatal conductance; V c,max, maximum rate of carboxylation; J max, maximum rate of electron transport; TPU, rate of thiose phosphate utilization; F v '/F m ', photochemical efficiency of open reaction centers of photosystem (PS) II; F v/F m, maximal photochemistry efficiency; LAR, leaf area ratio; LARMR, leaf area and root mass ratio; LMR, leaf mass ratio; RGR, relative growth rate; RMR, root mass ratio; SLA, specific leaf area; SMR, stem mass ratio; SSL, specific stem length; TDW, total plant biomass weight; WUEi, intrinsic water use efficiency; WUEt, total biomass water use efficiency. NW−60, NW−30, NW−15, NW0, NW15, NW30, NW60 denote −60 %, −30 %, −15 %, 0 %, 15 %, 30 %, and 60 % of watering relative to mean precipitation in the local site over 30 years with normal/ambient CO2 concentration; while EW−60, EW−30, EW-15, EW0, EW15, EW30, EW60 are those with elevated CO2

Plant growth analysis

Plant growth was increased significantly by applying water under both ambient and elevated CO2 (Fig. 2a). Elevated CO2 increased plant biomass by 21.6 %, 30.6 %, 32.3 %, 49.7 %, 52.1 %, 18.3 %, and 13.2 % in the W−60, W−30, W−15, W0, W15, W30, W60 watering treatments, respectively, indicating that the relationship between stimulation by CO2 enrichment and water status was a well-fitted quadratic function with higher points under moderate water change but declining under both water deficit and well-watered conditions. According to GLM ANOVA, CO2 concentration and watering treatment alone each significantly affected plant growth (P < 0.01, Additional file 3: Table S2). Plant individual leaf area significantly decreased with water deficit, whereas CO2 had no significant or systematic effect in GLM ANOVA (Fig. 2b; Additional file 3: Table S2).

Effects of elevated CO2 on plant growth and its structure with water status gradient. a plant biomass; b leaf area; c LAR, leaf area and plant mass ratio; d LARMR, leaf area and root mass ratio. W−60, W−30, W−15, W0, W15, W30, and W60 represent −60 %, −30 %, −15 %, 0 %, 15 %, 30 %, and 60 % of watering relative to mean precipitation in the local site over 30 years. A GLM ANOVA between temperature and watering, and their interaction was show in Additional file 3: Table S2. Different lower case letters indicate differences between watering treatments across the two CO2 levels at P < 0.05 according to Duncan multiple range test. Vertical bars denote SE of the mean (n = 3–4)

From W−60 to W0, an increase in LAR with improving water status was observed under the ambient CO2 level; however, this increase trend seemed to be partly offset by elevated CO2 (Fig. 2c,). LARMR had a similar response to the water status gradient, and CO2 enrichment-induced attenuation of the response to water status change was also observed (Fig. 2d). Both watering and CO2 concentration had significant effects on these two parameters (P < 0.05, Additional file 3: Table S2).

Watering had a significant effect on SLA, with a maximum under moderate water status and a reduction under water deficit or increased watering (Fig. 3a). SSL was also significantly affected by watering treatment, decreasing linearly with increased water (Fig. 3b). However, ANOVA on SLA and SSL suggested elevated CO2 and the interaction of watering and CO2 had no significant effect (Additional file 3: Table S2). LMR increased, while RMR decreased, with increasing water; in contrast, elevated CO2 seemed to reduce LMR and increase RMR in most cases except under W30 treatment (Fig. 3c, d). LMR and RMR were both significantly affected by watering, and LMR was also significantly affected by elevated CO2 (Additional file 3: Table S2).

Effects of elevated CO2 on plant organ structure traits (a, SLA, specific leaf area; b, SSL, specific stem length) and biomass allocation (c, LMR, leaf mass ratio; d, RMR, root mass ratio) with water status gradient. For watering treatment and bar details, see Fig. 2

Photosynthetic capacity, stomatal conductance, and intrinsic WUE

Watering had significant effects on the photosynthetic capacity parameters (V c,max, J max, TPU, A sat) with a maximum under W30 treatment, above or below which the values declined (Fig. 4). With elevated CO2, the photosynthetic capacity showed an increasing trend under relative water deficit, but a decrease under water surplus conditions (W30 and W60) (Fig. 4a–c, e). Stomatal conductance (g s) increased with increasing water, but showed a decreasing trend under W60, and was stimulated by elevated CO2, except under extreme drought and excess water conditions (W30 and W60) (Fig. 4f). WUEi was increased only under extreme drought with ambient CO2, but was generally elevated under the high CO2 concentration except in the W60 treatment (Fig. 4g). Watering had significant effects on V c,max, J max, TPU, A sat, and g s, but no significant effect on WUEi (Additional file 3: Table S2).

Effects of elevated CO2 on photosynthetic capacity (a, V c,max; b, J max; c, TPU; e, A sat), stomatal conductance (f, g s), intrinsic water use efficiency (g, WUEi), maximal photochemistry efficiency (d, F v/F m) and photochemical efficiency of open reaction centers of PSII (h, F' v/F' m) with water status gradient. V c,max, maximum rate of carboxylation; J max, maximum rate of electron transport, TPU, rate of thiose phosphate utilization; A sat, light-saturated maximum photosynthetic rate. For watering treatment and bar details, see Fig. 2

The two chlorophyll a fluorescence parameters—F v/F m and F' v/F' m—were only significantly decreased by severe water deficit. Elevated CO2 did not have a significant effect on either parameter, except a slight stimulation under relative water deficit. F v/F m was unchanged but F' v/F' m was decreased by elevated CO2 under relatively sufficient water conditions (Fig. 4d, h). Watering alone had significant effects on F v/F m and F' v/F' m, while CO2 concentration and the interaction of CO2 and water had no effect (Additional file 3: Table S2).

Mesophyll cell ultrastructure

No significant changes in mesophyll cell length were observed under changes in the two treatment factors (Additional file 4: Table S3). Cell width increased with elevated CO2, but decreased with reducing water except in the W30 and W60 treatments. There was a linear increase in cell area with increasing water under ambient CO2; under elevated CO2, cell area was often increased with improving water status, but decreased with excess water. Cell wall thickness (CWT) was decreased only under extreme drought (W−60), but was drastically increased by CO2 enrichment by 22.2 % across all watering treatments. The chloroplast number per cell was decreased by extreme drought, but markedly increased by CO2 enrichment in all watering treatments. Although the three chloroplast size parameters (length, width, and profile area) showed no systematic responses to the water status gradient, they were decreased under elevated CO2 in plants subjected to extreme and severe drought (W−60 and W−30) and increased in the excess water treatments (W30 and W60). The number of grana thylakoid membranes (TMN) was unaffected by watering treatment, but was decreased by elevated CO2 by an average of 22.9 % across all watering treatments. Water deficit and relative water surplus caused declines in the starch grain number per chloroplast profile (SGN), and no intact starch grains were found at W−60 with ambient CO2. Elevated CO2 led to decreases in SGN in the W−15 and W−30 treatments, but increases in the other water treatments, indicating that the effect of elevated CO2 strongly depended on water status. The plastoglobuli number per chloroplast (PGN) tended to decrease under ample watering at ambient CO2; elevated CO2 seemed to decrease PGN under severe drought (W−30 and W−60), but increase it under excess water treatments. Based on ANOVA, CO2 concentration, watering, and their interaction all significantly affected CWT and PGN. Elevated CO2 and watering both had significant effects on the chloroplast number, but their interaction did not. Cell width, cell area, and SGN was significantly affected only by watering, and TMN only by elevated CO2. Finally, watering, and its interaction with CO2 concentration significantly affected the chloroplast length (Additional file 4: Table S3).

Furthermore, as directly seen from the transmission electron micrographs of mesophyll cells at different magnification scales (Fig. 5), the cells tended to become more circular under normal watering conditions and produced more chloroplasts under elevated CO2 (Fig. 5a, d). The starch grains in chloroplasts were more numerous and larger under elevated CO2 than under ambient CO2, and less grana thylakoid membranes were observed at the high CO2 level (Fig. 5b, c, e, f). An abnormally swollen grana thylakoid possibly extruded by the greater starch grains was also observed (Fig. 5f). A cell wall with distinct layers appeared (Fig. 5c, f). In plants exposed to extremely severe water deficit (Fig. 5g–l), very few chloroplasts were observed (Fig. 5g), the chloroplast envelope seemed to be broken, most of the chloroplast grana were swollen, grana thylakoids were unclear and appeared to have disintegrated, the cell wall was abnormal with uneven layers, and a number of large plastoglobuli were observed (Fig. 5h, i). However, under severe drought accompanied by elevated CO2, partial recovery seemed to have occurred, i.e., the damage was partly alleviated (Fig. 5j–l).

Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of mesophyll cell in Agropyron cristatum leaves under control watering (W0, a-f) and severe water deficit (W−60, g-l) with ambient (a-c, g-i) and elevated CO2 (d-f, j-l) for whole mesophyll cell (a, d, g, j), whole chloroplast (b, e, h, k), and granum thylakoids (c, f, i, l). cl, chloroplast; cw, cell wall; gt, granum thylakoids; m, mitochondria; pl, plastoglobuli; s, starch grains. Bars, 5 μm (a, d, g, j), 0.5 μm (b, e, h, k), and 0.2 μm (c, f, i, l)

Total water use and biomass water use efficiency

Total water use, i.e., the actual evapotranspiration amount, significantly and linearly increased with increasing irrigation, from 304.6 to 654.5 g pot−1, a total increase of 114.9 % (Fig. 6a). However, elevated CO2 did not affect the total water use during the experimental period. WUEt tended to increase with increasing water, particularly at the high CO2 concentration (Fig. 6b). WUEt showed significant and strong relationships with total water use (Fig. 6c) and total biomass (Fig. 6d), particularly at the higher CO2 level, indicating that WUEt is often higher in plants with a faster growth rate, even greater water consumption and under an increased CO2 concentration.

Effects of elevated CO2 on total water use (a), total biomass water use efficiency (b, WUEt) with water status gradient; and WUEt relationships with total water use (c), and total biomass (d). In (a) and (b) panels, for watering treatment and bar details, see Fig. 2

Discussion

Our experiment on the effects of elevated CO2 on plants under various watering regimes showed that plant growth and photosynthetic capacity were stimulated by elevated CO2 under moderate water changes relative to normal precipitation; however, over-watering or extreme water deficit diminished or even eliminated this stimulation. The damage from severe drought, i.e., chloroplast and grana thylakoid damage, was partially ameliorated under the high CO2 level. This mostly confirmed our first hypothesis. This response to water status gradient at a high CO2 concentration was reflected by combined changes in plant architecture, biomass allocation, stomatal behavior, CO2 assimilation, PSII photochemical process, cell organelle structure, and water use efficiency (WUE), demonstrating highly synergistic changes at multiple scales. This coordinated response pattern may partly support our second hypothesis. Our results provide a deeper insight into the effects of varying water status on the response to CO2 enrichment, from cell ultrastructure to in vivo photosynthetic physiology and whole plant growth, highlighting that various aspects of the comprehensive responses of the dominant species need to be considered when assessing and projecting terrestrial ecosystem responses to climatic change, particularly in arid regions.

Stomatal conductance

A reduction in g s under enhanced CO2 can improve plant water status, thereby ameliorating the adverse effects of soil water deficiency on plant growth and physiological activity [8, 58]. As reported by Easlon et al. [59], a low g s coupled with high photosynthetic capacity in A. thaliana plants growing under elevated CO2 might result from more conservative N investment in the photosynthetic apparatus. In the present experiment, the marked g s decline due to water deficit seemed to be alleviated by elevated CO2, implying that increased CO2 has a protective role in drought-stressed leaves (Fig. 4f). In Liquidambar styraciflua plants, however, severe drought can lead to excessive stomatal closure and accelerated leaf senescence that may offset the benefits of CO2 enrichment for saving water [60]. The lack of benefit from increased CO2 to drought-stricken plants may be attributable to a lack of stomatal regulation [61]. Thus, the effect of elevated CO2 on the stomatal response to water change may depend on the species and extent of water deficit [58], but this needs to be explored further.

A marked decline in g s under severe water deficit in close parallel with photosynthetic capacity may reflect the coexistence of stomatal and mesophyll limitations on photosynthesis (Fig. 4), in agreement with Flexas and Medrano [62]. Their results indicated that non-stomatal limitations including decreased photochemistry and Rubisco activity corresponded with decreases in g s, particularly below 100 mmol m−2 s−1. Photosynthetic mesophyll limitations, such as decreases in both photosynthetic activity and cell size, may play a major role in photosynthetic depression [63], which is almost in agreement with the present results. A recent report showed that Ramonda nathaliae plants with smaller stomata had higher resistance to drought than R. serbica [64], in line with the reductions in mesophyll cell size and g s under severe drought in the present experiment (Additional file 4: Table S3). Thus, an associated change in cell size and stomatal behavior might confer a highly adaptive response to climate change.

In vivo physiological capacity

Photosynthetic capacity parameters such as A sat, V cmax J max, and TPU are inhibited under extreme and severe drought, but elevated CO2 can partly alleviate this inhibition [4, 24, 26, 65, 66]. However, in the present results, although elevated CO2 increased the photosynthetic capacity under severe and moderate drought and control treatments, it had no significant effect, or caused a decrease, under surplus watering conditions (Fig. 4). As reported previously, the photosynthetic capacity was decreased under elevated CO2 in Eucalyptus seedlings grown under well-watered but not water-stressed conditions [46]. Thus, the positive effects of elevated CO2 on photosynthesis may favor plants exposed to a moderate range of water statuses—from severe to moderate water deficit stress.

The effect of elevated CO2 on in vivo chlorophyll a fluorescence is also uncertain. For example, the maximal photochemical efficiency of PSII (F v/F m) was increased by elevated CO2 in poplar seedlings [67]. However, chlorophyll fluorescence showed no changes under elevated CO2 in Scots pine needles [68] and some grasses [26]. Roden and Ball [46] showed that elevated CO2 led to a reduction of F v/F m in amply watered Eucalyptus seedlings, but no effect was found under drought. No significant differences in F v/F m were found in control and water-deprived Phaseolus vulgaris plants, although plant fresh weight decreased approximately 30 % in water-stressed conditions [69], suggesting that other metabolic processes related to growth, rather than PSII photochemical activity, might play a critical role in the response to water deficit stress. Our findings indicated that CO2 enrichment had no effect on F v/F m, and even inhibited the photochemical efficiency of open reaction centers of PSII (F′v/F′m) in relatively well-watered plants, but had a stimulatory effect under relative water deficit (Fig. 4h). Moreover, we found that accelerated accumulation in starch grains might damage the chloroplast structure under well-watered conditions, which might partly explain the depression of PSII activity.

In Rakić et al. [64], a reduction in F v/F m occurred only in severely drought-stressed resurrection plants, consistent with our results in which a dramatic decline in F v/F m and F′v/F′m appeared only under extreme water deficit. Therefore, a drastic decline occurs only in plants subjected to extreme environmental stress, suggesting that these two parameters might not be good indicators of moderate water status changes. Elevated CO2 might not affect or might decrease these parameters, possibly because of decreased leaf thickness (greater SLA) or down-regulation of photosynthetic potential [26].

Organelle structure changes

The chloroplast, a compulsory light-harvesting organelle, can be easily and seriously affected by elevated CO2 [70, 71]. Many previous studies have shown that elevated CO2 could increase the number of chloroplasts in mesophyll cells [47, 70, 72, 73], which was also confirmed by the current study (Additional file 4: Table S3, Fig. 5). However, the mechanism by which elevated CO2 positively regulates chloroplast numbers still remains unclear [47, 72]. Some reports have suggested it results from stimulation of chloroplast biogenesis processes [47, 74]. Additionally, there is other evidence for this abnormal change induced by increased CO2: a drastic increase in the amount of chloroplast stroma thylakoid membranes has been found relative to those in lower CO2 levels [70]. Damage to chloroplast ultrastructure can also occur under elevated CO2, partly as a result of increased starch grain size and numbers through accelerated starch accumulation in chloroplasts [47]. Enhanced accumulation of starch grains within chloroplasts by elevated CO2 can induce distortion of grana thylakoids, with plants exposed to a high CO2 level often having a low A net [71]. In our current results, the increase in photosynthetic capacity was in agreement with the more numerous and larger starch grains in the chloroplasts of well-watered plants under the high CO2 level. It could be reasoned that starch accumulation might not be enough to limit the increase in photosynthesis induced by CO2 enrichment. However, this phenomenon would disappear under water deficit stress. Moreover, extremely severe water deficit can damage mesophyll cells, resulting in abnormal and disorganized cell organelles including chloroplasts and their grana [75], which was confirmed by the current experiment. However, this damage was partly ameliorated by elevated CO2, implying that plants have a strong dependence on the combination of CO2 concentration and water status.

Plant structural traits and associations with physiological activities

Interestingly, LARMR increased with increasing water supply but decreased at the high CO2 level (Fig. 2d), reflecting different effects on the biomass investment balance between the light trapping organs and resource element-deriving organs from the two climatic factors [49, 76]. This indicates that elevated CO2 might negate the enhanced investment in light-intercepting organs under an over-watering regime in this species, in line with our earlier study [26]. PCA can not only unveil the extent and directions of correlations among plant structural and functional traits, but also distinguish the effects of treatment factors or their combinations from the projections, highlighting the importance of this useful analysis tool [23, 26, 57]. Here, for example, RMR and SMR had opposite distributions in the PC loadings (Fig. 1a), possibly reflecting the carbon allocation trade-off between root and stem organs [27]. Moreover, we found positive close relationships between plant structural traits and functional traits such as photosynthetic activities and g s; they were all positively related with PC1, which might highlight their coordinated changes under different climatic change factors (Fig. 1a). Close associations between morphological/structural and functional traits have been widely reported, depending on the species and environment [26, 77–79]. Our results again highlight that multiple variables at different scales might together play a critical role in the adaptive response to global change by balancing or offsetting each other.

Water use efficiency

Elevated CO2 can improve plant water status by reducing g s and thereby increasing WUE to ameliorate the adverse effects on plant growth and physiological processes from stress factors alone and in combination [4, 8, 58]. Water status also mediated the effectiveness of rising CO2 by coupling the processes of gas exchange and leaf enlargement. Nevertheless, the pros and cons of acclimation to changes in water conditions might coexist in plant responses to elevated CO2; leaf area enlargement induced by CO2 might exaggerate water use, while decreased g s would promote WUEi [15, 58]. However, WUEi might decline under severe drought in some relict plant species exposed to elevated CO2 [61]. In the present experiment, both WUEi and WUEt were increased by elevated CO2, implying that the promotion of A net and plant biomass by elevated CO2 might play a dominant role.

In the same steppe, conflicting results can occur because of different data types. For example, field rain use efficiency (RUE) increased with increasing MAP across different vegetation types, but decreased across different years in a given site, particularly in drier areas [40, 80]. Decreased RUE with increasing precipitation can be due to low productivity or other resource limitations such as N deficit [80]. WUEt and RMR increased significantly with decreasing precipitation, but decreased with elevated CO2 [27]. In the present experiment, however, we found that the increase of WUEt with increases in both water use and plant biomass (Fig. 6), particularly at a high CO2 level, might explain the resource limitation to WUE; both a water use increase and CO2 enrichment, as increases in available resources, might promote WUE by stimulating photosynthetic capacity and plant growth. Furthermore, our results indicated that although WUEt and WUEi showed a similar response to elevated CO2, the former was more sensitive, implying that WUEt might be a better indicator than WUEi for assessing responses to climate change [81].

Elevated CO2 mitigation of severe drought

Elevated CO2 can ameliorate the negative effects of environmental stresses including severe water deficit in many different plant functional types or species such as the desert shrubs Caragana intermedia and Caragana microphylla [26, 82], the C3 perennial grasses L. chinensis and Stipa grandis [26, 27], and the C4 grass species Cleistogenes squarrosa [26]. The current experiment confirmed this amelioration due to CO2 enrichment in a C3 perennial grass from the same steppe as earlier experiments [26, 27, 82]. However, this amelioration was not observed in other reports on species such as some relict species [61], Populus deltoides [83], L. styraciflua [60], and Eucalyptus radiata [81]. Moreover, CO2 enrichment had a negligible effect on the response of E. radiata seedlings to drought, and did not alleviate the deleterious effects of drought due to rising temperature [81]. Thus, high CO2 may protect against or exacerbate stress effects, depending on different plant functional types and species.

A previous report showed that the growth of a dominant perennial shrub in a Mojave Desert ecosystem was doubled by a 50 % increase in CO2 only in a drier year [13]. In the present study, although elevated CO2 stimulated plant growth and photosynthetic activity in water deficit-treated plants, it had an inhibitory effect on the amply watered plants. This again indicates that CO2 enrichment may be more beneficial in drought conditions, implying that elevated CO2 may eliminate drought-induced negative plant responses. Thus, the allocation response to rising CO2 may also depend on water status. However, in a recent report, elevated CO2 productivity did no significantly modify the effects from soil water status in mesic grassland, semi-arid grassland, and xeric shrubland [84]. Taken together, these results suggest the integrated effects of elevated CO2 and water status on plants may be highly species- and habitat-specific.

Conclusions

Elevated CO2 can improve plant water status and therefore stimulate various physiological and ecological processes from the organelle to cell, organ and plant individual level. However, this stimulation is strongly dependent on water status. Elevated CO2 generally increased the growth and photosynthetic physiological parameters of A. cristatum such as V cmax, A sat, J max, gs, TPU, and F v/F m at severe to moderate water status, but had no effect on or even decreased these parameters in over-watering conditions. This indicates that CO2 enrichment can often ameliorate deleterious drought effects under moderate water deficit, but not extreme drought or over-watering conditions, and that plant morphological and structural alterations, and carbon allocation may be involved in this adaptive regulation. Our results for a dominant species from a degraded steppe suggest that water status changes such as severe drought or over-watering events might fundamentally contribute to the effects of CO2 enrichment on key physiological activities, cell structure, plant growth and even survival in a future climatic context, even completely reversing the direction of the effect. Our results highlight that CO2 fertilization’s dependency on water status should be considered when projecting plant responses to climate change. These findings contribute to our understanding of plant responses to global climate change, and may be useful in vulnerable ecosystem management.

Abbreviations

A sat, light-saturated maximum photosynthetic rate; F′ v/F′ m, photochemical efficiency of open reaction centers of PSII; F v/F m, maximal PSII photochemical efficiency; g s, stomatal conductance; J max, maximum rate of electron transport; LAR, leaf area and plant total mass ratio; LARMR, leaf area and root mass ratio; LMR, leaf mass ratio; PCA, principal component analysis; RGR, relative growth rate; RMR, root mass ratio; SLA, specific leaf area; SMR, stem mass ratio; SSL, specific stem length; TPU, rate of thiose phosphate utilization; V c,max, maximum rate of carboxylation; WUEi, intrinsic water use efficiency; WUEt, total biomass water use efficiency.

References

IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In: Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner G-K, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM, editors. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of working Group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge, United Kingdom, and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

Curtis PS, Wang X. A meta-analysis of elevated CO2 effects on woody plant mass, form, and physiology. Oecologia. 1998;113:299–313.

Long SP, Ainsworth EA, Rogers A, Ort DR. Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide: plants FACE the future. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:591–628.

Xu ZZ, Shimizu H, Yagasaki Y, Ito S, Zheng YR, Zhou GS. Interactive effects of elevated CO2, drought, and warming on plants. J Plant Growth Regul. 2013;32:692–707.

Peñuelas J, Sardans J, Estiarte M, Ogaya R, Carnicer J, Coll M, et al. Evidence of current impact of climate change on life: a walk from genes to the biosphere. Global Change Biol. 2013;19:2303–38.

Way DA, Oren R, Kroner Y. The space-time continuum: the effects of elevated CO2 and temperature on trees and the importance of scaling. Plant Cell Environ. 2015;38(6):991–1007.

Saxe H, Ellsworth DS, Heath J. Trees and forest functioning in an enriched CO2 atmosphere. New Phytol. 1998;139:395–436.

Ainsworth EA, Rogers A. The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising [CO2]: mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant Cell Environ. 2007;30:258–70.

DaMatta FM, Godoy AG, Menezes-Silva PE, Martins SC, Sanglard LM, Morais LE, et al. Sustained enhancement of photosynthesis in coffee trees grown under free-air CO2 enrichment conditions: disentangling the contributions of stomatal, mesophyll, and biochemical limitations. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:341–52.

Luo Y, Su B, Currie WS, Dukes JS, Finzi A, Hartwig A, Hungate B, McMurtrie RE, Oren R, Parton WJ, Pataki DE, Shaw MR, Zak DR, Field CB. Progressive nitrogen limitation of ecosystem responses to rising atmospheric carbon dioxide. Bioscience. 2004;54:731–9.

Ainsworth EA, Rogers A, Nelson R, Long SP. Testing the ‘source-sink’ hypothesis of down-regulation of photosynthesis in elevated [CO2] in the field with single gene substitutions in Glycine max. Agr Forest Meteorol. 2004;122:85–94.

Benlloch-Gonzalez M, Berger J, Bramley H, Rebetzke G, Palta JA. The plasticity of the growth and proliferation of wheat root system under elevated CO2. Plant Soil. 2014;374:963–76.

Smith SD, Huxman TE, Zitzer SF, Charlet TN, Housman DC, Coleman JS, et al. Elevated CO2 increases productivity and invasive species success in an arid ecosystem. Nature. 2000;408:79–82.

Morgan JA, Milchunas DG, LeCain DR, West M, Mosier AR. Carbon dioxide enrichment alters plant community structure and accelerates shrub growth in the shortgrass steppe. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14724–9.

Manea A, Leishman MR. Competitive interactions between established grasses and woody plant seedlings under elevated CO2 levels are mediated by soil water availability. Oecologia. 2015;177:499–506.

Reyes-Fox M, Steltzer H, Trlica MJ, McMaster GS, Andales AA, LeCain DR, Morgan JA. Elevated CO2 further lengthens growing season under warming conditions. Nature. 2014;510:259–62.

Xu ZZ, Zhou GS. Responses of photosynthetic capacity to soil moisture gradient in perennial rhizome grass and perennial bunchgrass. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:21.

Conroy JP, Smillie RM, Küppers M, Bevege DI, Barlow EW. Chlorophyll a fluorescence and photosynthetic and growth responses of Pinus radiata to phosphorus deficiency, drought stress, and high CO2. Plant Physiol. 1986;81:423–9.

Ge Z-M, Zhou X, Kellomäki S, Wang K-Y, Peltola H, Martikainen PJ. Responses of leaf photosynthesis, pigments and chlorophyll fluorescence within canopy position in a boreal grass (Phalaris arundinacea L.) to elevated temperature and CO2 under varying water regimes. Photosynthetica. 2011;49:172–84.

Salazar-Parra C, Aguirreolea J, Sánchez-Díaz M, JoséIrigoyen J, Morales F. Climate change (elevated CO2, elevated temperature and moderate drought) triggers the antioxidant enzymes response of grapevine cv. Tempranillo, avoiding oxidative damage. Physiol Plant. 2012;144:99–110.

Lee SH, Woo SY, Je SM. Effects of elevated CO2 and water stress on physiological responses of Perilla frutescens var. japonica HARA. Plant Growth Regul. 2015;75:427–34.

Wullschleger SD, Tschaplinski TJ, Norby RJ. Plant water relations at elevated CO2-implications for water-limited environments. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25:319–31.

AbdElgawad H, Farfan-ignolo ER, de Vos D, Asard H. Elevated CO2 mitigates drought and temperature-induced oxidative stress differently in grasses and legumes. Plant Sci. 2015;231:1–10.

AbdElgawad H, Zinta G, Beemster GTS, Janssens IA, Asard H. Future climate CO2 levels mitigate stress impact on plants: increased defense or decreased challenge? Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:556. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.00556.

Morgan JA, Pataki DE, Körner CH, Clark H, Del Grosso SJ, Grünzweig JM, et al. Water relations in grassland and desert ecosystems exposed to elevated atmospheric CO2. Oecologia. 2004;140:11–25.

Xu ZZ, Shimizu H, Ito S, Yagasaki Y, Zou CJ, Zhou GS, Zheng YR. Effects of elevated CO2, warming and precipitation change on plant growth, photosynthesis and peroxidation in dominant species from North China grassland. Planta. 2014;239:421–35.

Li Z, Zhang Y, Yu D, Zhang N, Lin J, Zhang J, et al. The influence of precipitation regimes and elevated CO2 on photosynthesis and biomass accumulation and partitioning in seedlings of the rhizomatous perennial grass Leymus chinensis. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103633.

Leakey AD, Uribelarrea M, Ainsworth EA, Naidu SL, Rogers A, Ort DR, Long SP. Photosynthesis, productivity, and yield of maize are not affected by open-air elevation of CO2 concentration in the absence of drought. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:779–90.

Hasegawa T, Sakai H, Tokida T, Nakamura H, Zhu C, Usui Y, et al. Rice cultivar responses to elevated CO2 at two free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE) sites in Japan. Funct Plant Biol. 2013;40:148–59.

Bishop KA, Leakey AD, Ainsworth EA. How seasonal temperature or water inputs affect the relative response of C3 crops to elevated [CO2]: a global analysis of open top chamber and free air CO2 enrichment studies. Food Energy Security. 2014;3:33–45.

Dormaar JF, Naeth MA, Willms WD, Chanasyk DS. Effect of native prairie, crested wheatgrass (Agropyron Cristatum (L.) Gaertn.) and Russian wildrye (Elymus Junceus Fisch.) on soil chemical properties. J Range Manag. 1995;48:258–63.

Krzic M, Broersma K, Thompson DJ, Bomke AA. Soil Properties and species diversity of grazed crested wheatgrass and native rangelands. J Range Manag. 2000;53:353–8.

Wang W, Liu ZL, Hao DY, Liang CZ. Research on the restoring succession of the degenerated grassland in Inner Mongolia II. Analysis of the restoring processes. Acta Phytoecol Sin. 1996;20:460–71.

Bai Y, Han X, Wu J, Chen Z, Li L. Ecosystem stability and compensatory effects in the Inner Mongolia grassland. Nature. 2004;431:181–4.

Xu ZZ, Zhou GS. Combined effects of water stress and high temperature on photosynthesis, nitrogen metabolism and lipid peroxidation of a perennial grass Leymus chinensis. Planta. 2006;224:1080–90.

Kang L, Han X, Zhang Z, Sun OJ. Grassland ecosystems in China: review of current knowledge and research advancement. Philos T R Soc B. 2007;362:997–1008.

Li Z, Ma W, Liang C, Liu Z, Wang W, Wang L. Long-term vegetation dynamics driven by climatic variations in the Inner Mongolia grassland: findings from 30-year monitoring. Landscape Ecol. 2015;30:1701–11.

Liu B, Xu M, Henderson M, Qi Y. Observed trends of precipitation amount, frequency, and intensity in China, 1960–2000. J Geophys Res. 2005;110, D08103. doi:10.1029/2004JD004864.

Yan L, Chen S, Xia J, Luo Y. Precipitation regime shift enhanced the rain pulse effect on soil respiration in a semi-arid steppe. PLoS One. 2014;9(8), e104217. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104217.

Bai Y, Wu J, Xing Q, Pan Q, Huang J, Yang D, Han X. Primary production and rain use efficiency across a precipitation gradient on the Mongolia plateau. Ecology. 2008;89:2140–53.

Peuke AD, Gessler A, Rennenberg H. The effect of drought on C and N stable isotopes in different fractions of leaves, stems and roots of sensitive and tolerant beech ecotypes. Plant Cell Environ. 2006;29:823–35.

Tubiello FN, Amthor JS, Boote KJ, Donatelli M, Easterling W, Fischer G, Gifford RM, Howden M, Reilly J, Rosenzweig C. Crop response to elevated CO2 and world food supply. A comment on “Food for Thought…” by Long et al., Science 312:1918–1921, 2006. Euro J Agron. 2007;26:215–23.

Messerli J, Bertrand A, Bourassa J, Bélanger G, Castonguay Y, Tremblay G, et al. Performance of low-cost open-top chambers to study long-term effects of carbon dioxide and climate under field conditions. Agron J. 2015;107:916–20.

Long SP, Ainsworth EA, Leakey ADB, Nösberger J, Ort DR. Food for thought: Lower-than-expected crop yield stimulation with rising CO2 concentrations. Science. 2006;312:1918–21.

Ainsworth EA, Leakey ADB, Ort DR, Long SP. FACE-ing the facts: inconsistencies and interdependence among field, chamber and modeling studies of elevated [CO2] impacts on crop yield and food supply. New Phytol. 2008;179:5–9.

Roden JS, Ball MC. The effect of elevated [CO2] on growth and photosynthesis of two Eucalyptus species exposed to high temperatures and water deficits. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:909–19.

Teng N, Wang J, Chen T, Wu X, Wang Y, Lin J. Elevated CO2 induces physiological, biochemical and structural changes in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2006;172:92–103.

Zhao B, Kondo M, Maeda M, Ozaki Y, Zhang J. Water-use efficiency and carbon isotope discrimination in two cultivars of upland rice during different developmental stages under three water regimes. Plant Soil. 2004;261:61–75.

Poorter L. Growth responses of 15 rain-forest tree species to a light gradient: the relative importance of morphological and physiological traits. Funct Ecol. 1999;13:396–410.

Aranjuelo I, Ebbets AL, Evans RD, et al. Maintenance of C sinks sustains enhanced C assimilation during long-term exposure to elevated [CO2] in Mojave Desert shrubs. Oecologia. 2011;167:339–54.

van Kooten O, Snel JFH. The use chlorophyll fluorescence nomenclature in plant stress physiology. Photosynth Res. 1990;25:147–50.

Maxwell K, Johnson GN. Chlorophyll fluorescence—a practical guide. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:659–68.

Sharkey TD, Bernacchi CJ, Farquher FD, Singsaas EL. Fitting photosynthetic carbon dioxide response curves for C3 leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 2007;30:1035–40.

Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta. 1980;149:78–90.

Reynolds ES. The use of lead citrate at high pH as an electron-opaque stain in electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1963;17:208–12.

Jolliffe IT. Principal component analysis. New York: Springer; 2002.

Vile D, Pervent M, Belluau M, Vasseur F, Bresson J, Muller B, Granier C, Simonneau T. Arabidopsis growth under prolonged high temperature and water deficit: independent or interactive effects? Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35:702–18.

Xu ZZ, Jiang YL, Jia BR, Zhou GS. Elevated-CO2 response of stomata and its dependence on environmental factors. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:657. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.00657.

Easlon HM, Carlisle E, McKay J, Bloom A. Does low stomatal conductance or photosynthetic capacity enhance growth at elevated CO2 in Arabidopsis thaliana? Plant Physiol. 2015;167:793–9.

Warren JM, Norby RJ, Wullschleger SD. Elevated CO2 enhances leaf senescence during extreme drought in a temperate forest. Tree Physiol. 2011;31:117–30.

Linares JC, Delgado-Huertas A, Camarero JJ, Merino J, Carreira JA. Competition and drought limit the response of water-use efficiency to rising atmospheric carbon dioxide in the Mediterranean fir Abies pinsapo. Oecologia. 2009;161:611–24.

Flexas J, Medrano H. Drought-inhibition of photosynthesis in C3 plants: stomatal and non-stomatal limitation revisited. Ann Bot. 2002;89:183–9.

Jacob J, Lawlor DW. Stomatal and mesophyll limitations of photosynthesis in phosphate deficient sunflower, maize and wheat plants. J Exp Bot. 1991;42:1003–11.

Rakić T, Gajic G, Lazarevic M, Stevanovic B. Effects of different light intensities, CO2 concentrations, temperatures and drought stress on photosynthetic activity in two paleoendemic resurrection plant species Ramonda serbica and R-nathaliae. Environ Exp Bot. 2015;109:63–72.

Markelz RJ, Strellner RS, Leakey AD. Impairment of C-4 photosynthesis by drought is exacerbated by limiting nitrogen and ameliorated by elevated [CO2] in maize. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:3235–46.

Xu ZZ, Jiang YL, Zhou GS. Response and adaptation of photosynthesis, respiration, and antioxidant systems to elevated CO2 with environmental stress in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:701. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00701.

Ceulemans R, Jiang XN, Shao BY. Growth and physiology of one-year-old poplar (Populus) under elevated atmospheric CO2 levels. Ann Bot. 1995;75:609–17.

Luomala EM, Laitinen K, Kellomäki S, Vapaavuori E. Variable photosynthetic acclimation in consecutive cohorts of Scots pine needles during 3 years of growth at elevated CO2 and elevated temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 2003;26:645–60.

Verdoy D, Lucas MM, Manrique E, Covarrubias AA, De Felipe MR, Pueyo JJ. Differential organ-specific response to salt stress and water deficit in nodulated bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Plant Cell Environ. 2004;27:757–67.

Griffin KL, Anderson OR, Gastrich MD, Lewis JD, Lin G, Schuster W, et al. Plant growth in elevated CO2 alters mitochondrial number and chloroplast fine structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2473–8.

Sharma N, Sinha PG, Bhatnagar AK. Effect of elevated [CO2] on cell structure and function in seed plants. Clim Change Environ Sustain. 2014;2:69–104.

Bockers M, Capková V, Tichá I, Schäfer C. Growth at high CO2 affects the chloroplast number but not the photosynthetic efficiency of photoautotrophic Marchantia polymorpha culture cells. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1997;48:103–10.

Lin JX, Jach ME, Ceulemans R. Stomatal density and needle anatomy of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) are affected by elevated CO2. New Phytol. 2001;150:665–74.

Wang XZ, Anderson OR, Griffin KL. Chloroplast numbers, mitochondrion numbers and carbon assimilation physiology of Nicotiana sylvertris as affected by CO2 concentration. Environ Exp Bot. 2004;51:21–31.

Xu ZZ, Zhou GS, Shimizu H. Effects of soil drought with nocturnal warming on leaf stomatal traits and mesophyll cell ultrastructure of a perennial grass. Crop Sci. 2009;49:1843–51.

Poorter H, Jagodziński A, Ruíz-Peinado R, Kuyah S, Luo Y, Oleksyn J, Usoltsev V, Buckley T, Reich PB, Sack L. How does biomass allocation change with size and differ among species? An analysis for 1200 plant species from five continents. New Phytol. 2015;208:736–49.

Niinemets Ü, Sack L. Structural determinants of leaf light harvesting capacity and photosynthetic potentials. Prog Bot. 2006;67:385–419.

Sack L, Frole K. Leaf structural diversity is related to hydraulic capacity in tropical rainforest trees. Ecology. 2006;87:483–91.

Díaz S, Kattge J, Cornelissen JHC, Wright IJ, Lavorel S, Dray S, et al. The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature. 2016;529:167–71.

Huxman TE, Smith MD, Fay PA, Knapp AK, Shaw MR, Loik ME, et al. Convergence across biomes to a common rain-use efficiency. Nature. 2004;429:651–4.

Duan HL, Duursma RA, Huang GM, Smith RA, Choat B, O’Grady AP, Tissue DT. Elevated [CO2] does not ameliorate the negative effects of elevated temperature on drought-induced mortality in Eucalyptus radiata seedlings. Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37:1598–613.

Xu ZZ, Zhou GS, Wang YH. Combined effects of elevated CO2 and soil drought on carbon and nitrogen allocation of the desert shrub Caragana intermedia. Plant Soil. 2007;301:87–97.

Bobich EG, Barron-Gafford GA, Rascher KG, Murthy R. Effects of drought and changes in vapour pressure deficit on water relations of Populus deltoides growing in ambient and elevated CO2. Tree Physiol. 2010;30:866–75.

Fay PA, Newingham BA, Polley HW, Morgan JA, LeCain DR, Nowak RS, Smith SD. Dominant plant taxa predict plant productivity responses to CO2 enrichment across precipitation and soil gradients. AoB Plants. 2015;7:plv027. doi:10.1093/aobpla/plv027.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Hui Wang, Yaohui Shi, Xiaomin lv, Zhixiang Yang, and Jian Song for their assistant works during the current experiment. We also greatly appreciate the anonymous reviewers and Dr. Giles Johnson for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Funding

This research was jointly funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31170456), and China Special Fund for Meteorological Research in the Public Interest (Major projects) (GYHY201506001-3).

Availability of data and materials

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Authors’ contributions

JY, XZ and ZG conceived and designed the study; JY, XZ and LT conducted the experiment and performed the data analysis; JY and XZ drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The soil and seed collections from the field in our experiments are conducted in and permitted by Inner Mongolia Grassland Ecosystem Research Station, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing. No species are involved at risk of extinction in the present experiment. Others are not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Changes in soil relative water contents (SRWC) at ambient and elevated CO2 concentrations with a water status gradient during a given period. Measured at 17:00 every three days, the watering day, but before watering during a consecutive 10-day period. W−60, W−30, W−15, W0, W15, W30, and W60 represent −60 %, −30 %, −15 %, 0, 15 %, 30 %, and 60 % of watering relative to mean precipitation in the local site over 30 years. Vertical bars denote SE of the mean (n = 3–4). GLM ANOVA refers to Additional file 2: Table S1. (DOCX 51 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Tests of between-subjects effects of CO2 concentration and watering on soil relative water content (SRWC) from GLM ANOVA. Bold font for P values indicates significance at P < 0.05. (DOCX 17 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S2.

Tests of between-subjects effects of CO2 concentration and watering on plant functional traits, physiological activity parameters from GLM ANOVA. Bold font for P values indicates significance at P < 0.05. (DOCX 24 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S3.

Mesophyll cell ultrastructure in Agropyron cristatum grown under ambient and elevated CO2 concentrations with water status gradient. (DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Y., Xu, Z., Zhou, G. et al. Elevated CO2 can modify the response to a water status gradient in a steppe grass: from cell organelles to photosynthetic capacity to plant growth. BMC Plant Biol 16, 157 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-016-0846-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-016-0846-9