Abstract

Background

The genus Brassica mainly comprises three diploid and three recently derived allotetraploid species, most of which are highly important vegetable, oil or ornamental crops cultivated worldwide. Despite being extensively studied, the origination of B. napus and certain detailed interspecific relationships within Brassica genus remains undetermined and somewhere confused. In the current high-throughput sequencing era, a systemic comparative genomic study based on a large population is necessary and would be crucial to resolve these questions.

Results

The chloroplast DNA and mitochondrial DNA were synchronously resequenced in a selected set of Brassica materials, which contain 72 accessions and maximally integrated the known Brassica species. The Brassica genomewide cpDNA and mtDNA variations have been identified. Detailed phylogenetic relationships inside and around Brassica genus have been delineated by the cpDNA- and mtDNA- variation derived phylogenies. Different from B. juncea and B. carinata, the natural B. napus contains three major cytoplasmic haplotypes: the cam-type which directly inherited from B. rapa, polima-type which is close to cam-type as a sister, and the mysterious but predominant nap-type. Certain sparse C-genome wild species might have primarily contributed the nap-type cytoplasm and the corresponding C subgenome to B. napus, implied by their con-clustering in both phylogenies. The strictly concurrent inheritance of mtDNA and cpDNA were dramatically disturbed in the B. napus cytoplasmic male sterile lines (e.g., mori and nsa). The genera Raphanus, Sinapis, Eruca, Moricandia show a strong parallel evolutional relationships with Brassica.

Conclusions

The overall variation data and elaborated phylogenetic relationships provide further insights into genetic understanding of Brassica, which can substantially facilitate the development of novel Brassica germplasms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The genus Brassica in Brassicaceae family is one of the most agriculturally important plant genera worldwide, which mainly comprises three diploid and three allotetraploid species, as described in the genetic model of U’s Triangle [1]. Brassica napus (AACC, 2n = 38), B. juncea (AABB, 2n = 36) and B. carinata (BBCC, 2n = 34) are thought to be generated by interspecific hybridizations between each two of the three basic diploid progenitors: B. rapa (AA, 2n = 20), B. oleracea (CC, 2n = 18) and B. nigra (BB, 2n = 16). The current abundant genomic and phenotypic diversifications have given rise to highly diverse crops of vegetable, oil, ornamental, fodder and fertilizer use types. To date, B. napus (rapeseed) has become to be the second largest vegetable oil crop worldwide [2]. Recently, the release of certain reference genome sequences has drived Brassica as an ideal model for studying polyploidy [3,4,5,6,7].

B. napus is supposed to originate from certain kind of hybridization between B. rapa and B. oleracea, which co-existed in European Mediterranean coastwise regions, at approximately 10,000 years ago [4]. Then it has diffused worldwide (mainly to Asia, America and Australia), and eventually formed several ecological and morphological types, which mainly include winter, spring and semi-winter ecotypes or oil-use, root-tuberous and leafy morphotypes. Recently, extensive resequencing and analyses on nuclear DNA concerning the mechanisms for the progenitors, evolution and improvement of this versatile crop have been performed. Phylogenomic analyses combining diverse B. napus and its potential progenitors revealed that winter type rapeseed might be the original form of B. napus, European turnip ancestor might donate the A subgemone, the origin of C subgenome is mysterious and it was currently supposed to evolve from a common ancestor of cultivated C-genome species (kohlrabi, cauliflower, broccoli, and Chinese kale) [8]. The A and C subgenomes evolved asymmetrically and higher genetic diversity was identified in A subgenome [9].

To date, the genuine originating mechanisms of B. napus remain largely unresolved. The frequent post-formation introgression events occurred during human breeding consequentially confused the recovery of the originating trajectory of B. napus at nuclear genome level. Cytoplasmic DNA in plant cell, especial for chloroplast DNA (cpDNA), are structurally simple with a small genome size (100–300 kb) and stably inherited mostly in a uniparental pattern with nearly none recombination [10]. Thus, it has been extensively employed in the phylogenetic studies [11,12,13,14]. Genotyping by using six chloroplast SSR primer pairs or TILLING analysis, one most prevalent cpDNA haplotype was identified in B. napus [15, 16]. While, the B. napus of this same cpDNA haplotype generally formed an ambiguous clade, which did not group with the investigated B. rapa or B. oleracea accessions [17], implying its mysterious origin. A few B. napus accessions were grouped with the majority of B. rapa accessions suggested another independent cytoplasmic origin from B. rapa [9, 18], indicating that has multiplex maternal origins. The mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of B. napus has drawn much more attention for the extensive application of its cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) lines in the heterosis-driving hybrid breeding, mainly containing polima (pol), cam and nap mitotypes in the natural resources [17]. Nap mitotype is predominant in natural B. napus, However, it remains unsolved and were supposed to be from an unidentified or lost mitotype of B. rapa [19]. The nap mitotype was further judged to be derived from B. oleracea, since it was phylogenetically grouped with botrytis-type and capitata-type B. oleracea [20].

Apparently, the current above conclusions regarding the origin of nap-type B. napus are controversial and ambiguous. Previous cpDNA and mtDNA-based studies were separated and never been corresponded and integrated to accurately explore the multiply origin of B. napus. Cytoplasmic DNA and its corresponding cytonuclear interactions, are highly valuable for crop breeding not only due to its cause of cytoplasmic male sterility [21], but also in the association with certain agricultural traits, e.g., high seed-oil content in nap-type rapeseed [22] and plant resistance to adverse living environment. Here in this study, a well-chosen set of plant materials centering on B. napus have been synchronously resequenced at the cpDNA and mtDNA level, a systematic genetic investigation and an elaborate phylogenetic pedigree at intraspecific level have been constructed, with the purpose of improving our understanding of the whole Brassica genus.

Results

Sequencing of the diverse cytoplasmic Brassica DNA haplotypes

To distinguish the cytoplasmic DNA (cpDNA and mtDNA) haplotypes within Brassica genus, genotyping analysis through High Resolution Melting (HRM) method were performed in our germplasm collections (Figure S1). Primers were designed being targeted on a set of intra/inter-specific cpDNA polymorphic sites that were identified previously [16] (Table S1). Three major haplotypes were identified in approximately 480 worldwide B. napus accessions. Two major cpDNA haplotypes were identified in 180 B. rapa accessions, while 180 B. juncea accessions contain one major cpDNA haplotype. B. oleracea, B. carinata, B. nigra, B. maurorum (MM, 2n = 16), certain wild C-genome relatives and three B. napus cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) lines were treated as each with a distinct haplotype for the subsequent genome sequencing. B. cretica, B. incana, B. insularis and B. villosa represent the wild C-genome relatives. Polima [23, 24], nsa [25] and mori [26, 27] are the CMS lines. Certain relative materials, i.e. Eruca sativa (2n = 22), Raphanus sativus (2n = 18), Sinapis arvensis (2n = 24) and Moricandia arvensis (2n = 28), were also included to enrich this study (Table S2).

Cytoplasmic DNA was synchronously isolated from 72 accessions that represent for all major cytoplasmic haplotypes and morphological varieties (Table S2), using an optimized organelle isolation procedure (Materials and Methods). This method can substantially help to remove nuclei and balance the proportions of cpDNA and mtDNA content. Reads mapping analysis demonstrated that the isolated total DNA contains an average ratio of 37.2% chloroplast DNA and 3.4% mitochondrial DNA, respectively, which is approximately 5–10 times higher than the ratio of cytoplasmic DNA in the total leaf DNA [28]. The cytoplasmic DNA mixture was then subjected to the high-throughput sequencing (with average sequencing depths above 500 x, Table 1). The obtained paired-end reads (150 bp) were directly mapped to a tandem sequence gather, which consists of 10 published chloroplast genome sequences across Brassicaceae family. The mapped reads were extracted and de novo assembled by SOAPdenovo software package [29]. Generally, two or three large contigs were eventually generated for the chloroplast genomes. Gaps were directly filled through manual jointing of the overlapping ends of each two contiguous contigs, and then verified by Sanger sequencing of the gap-spanning PCR fragments. All the obtained chloroplast genome sequences are provided in Additional file 3 (Appendix A).

Genome-wide cytoplasmic (cpDNA and mtDNA) variations in Brassica

The chloroplast and mitochondrial genome sequences of a B. napus strain 51,218 [22], which is an intermediate breeding material of nap mitotype, were respectively used as reference sequences to call the overall cpDNA and mtDNA basic variants. The calling was conducted by standard BWA/Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) pipeline with manual inspection [30], and then randomly verified by Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP) analysis. A total of approximately 4700 reliable basic polymorphic sites, including 3880 SNP and 820 InDels, respectively, were identified for all the sequenced chloroplast haplotypes in Brassica genus. While, approximately 3400 polymorphic sites (2700 SNP and 700 InDels) were identified for the mitochondrial haplotypes (Table S3). The average SNP density in the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes was 25 and 12 SNPs per kilo base (kb), respectively. The chloroplast variants were uniformly distributed along the reference genome, except the two 26-kb large inverted repeat regions, IRa and IRb (Fig. 1), since these genomic regions were skipped due to the repetitive mapping of the same reads. The mitochondrial variants showed a comparatively even distribution pattern along the reference genome; however, their variation frequencies are obviously much higher at the regions containing the open reading frame (ORF) genes (Fig. 2).

Genomic distribution of the basic cpDNA variants in the sequenced materials. The map was drawn using Circos (http://circos.ca/). The innermost circle represents for the chloroplast genome map of B. napus strain 51,218. The inner bottle-green bars and outer laurel-green bars correspond to the distribution of SNPs and InDels within nonoverlapping 500-bp bins across the entire genome, respectively. The length of each bar denotes the total number of basic variants in a 500-bp region, take the value as 30 if it exceeds 30. None variants appeared in two inverted repeat regions, IRa (83–109 kb) and IRb (126–153 kb)

Genomic distribution of the basic mtDNA variants in the sequenced materials. The map was drawn using the same procedure as for Fig. 1. The innermost circle represents for the mitichondrial genome map of B. napus strain 51,218. The inner bottle-green bars and outer laurel-green bars correspond to the distribution of SNPs and InDels, respectively

Among the overall variants, 13.9 and 18.1% were identified as nonsynonymous for 47 cpDNA coding genes and 61 mtDNA coding genes, respectively. The materials of two B. napus mitochondrial haplotypes, below known as cam- and polima-types, possess approximately 300 basic variants when referring to B. napus strain 51,218 mitochondrial genome of nap-type. Polima-type is close to cam-type with a difference of only about 50 conserved cpDNA variants (Table S3). Consistent difference patterns were also found for cpDNA variants as for the three cytoplasmic types. KASP analysis using the primers targeted to the B. napus mitotype-corresponding mtDNA and cpDNA polymorphic sites detected that nap, cam and polima cytoplasms accounted for 87.1, 7.2 and 5.7% in the investigated B. napus population (Figure S2). Undoubtedly, nap-type is the predominant cytoplasmic DNA haplotype, as identified in previous studies [15, 16]. Most of the B. rapa materials are of the same cam-type in B. napus, another major haplotype accounting for a frequency of approximately 5.8% in the investigated B. rapa population has been identified and named as sarson-type hereinafter, since it mainly exists in B. rapa var. sarson accessions.

The phylogeny of Brassica genus conducted based on the whole chloroplast genomes

Analyses based on the whole chloroplast genomes or genome-wide variations instead of partial cpDNA fragments can infer a phylogeny with much higher resolution and reliability, even at lower taxonomic levels [14]. To forecast the evolutionary trajectories of Brassica crops, all the above-obtained whole chloroplast genomes were subjected to phylogenetic analysis. The phylogenetic trees tentatively conducted using the Maximum Likelihood method, neighbor-joining method and Bayesian method were almost identical. To reduce the calculating amount and avoid a corpulent tree, the trees comprising materials throughout each intra-species, Brassica genus and Brassicaceae family, respectively, were conducted stepwise by Maximum Likelihood method [31].

Chloroplast genome sequences of Raphanus sativus, Isatis tinctoria, Matthiola incana and Arabidopsis thaliana in Brassicaceae family (Data from NCBI, Additional file 3) served as outgroup to root the intra-specific trees. The results indicated that 13 B. rapa accessions, 14 B. juncea accessions, 24 B. napus accessions and 13 C-genome species each clustered well and were separately integrated into a species-specific group. The B. rapa separated a little branch containing only two accessions, which were classified as sarson-type cytoplasm mentioned above (Figure S3). The B. juncea accessions did not diverge any secondary branches, indicating a lack of cytoplasmic genetic diversity (Figure S4). The B. napus cluster were split into two large branches, one branch containing the nap-type lines (e.g., the nuclear-genome sequenced cultivars Darmor/AC489 and ZS11/AC457), another branch further split into two little branches, containing cam-type (e.g., Shengli Rape/AC32) and polima-type (e.g., Jianyang Rape/AC399) lines, respectively (Figure S5). All the investigated cultivated B. oleracea (e.g., Cauliflower, Broccoli, Cabbage, Kohlrabi) and part of the wild B. oleracea were shown with one nearly identical chloroplast genome sequence. However, the C-genome wild relatives (B. villosa, B. insularis, B. cretica and B. incana) each contains a distinct haplotype. All the C-genome species demonstrated a hierarchically clear pedigree, from B. villosa stepwise to the cultivated B. oleracea (Figure S6).

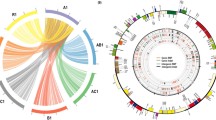

A part of the above intra-specific materials were selected capable of maximumly representing each their intraspecific genetic diversities, and then together with Brassica nigra, B. carinata and B. maurorum, were combined to construct a larger tree comprising of materials all over Brassica genus. The cpDNA sequence data for materials Root mustard-1 (B. juncea), Sarsons-1 (B. rapa), Broccoletto-3 (B. rapa), Black mustard (B. juncea) and Ethiopian mustard (B. carinata) were added from Li et al., [18] to enrich the whole phylogenetic tree. The results indicated that Brassica genus was mainly divided into three clades, from which the maternal origin of the three natural allotetraploid species can be clearly inferred (Fig. 3). All the B. rapa, B. juncea and quite a few B. napus accessions of both cam- and polima-type constitute Clade I, which further diverged two little branches containing B. rapa ssp. trilocularis (Sarsons) and polima-type B. napus, respectively. Three B. juncea accessions clustered only in Clade I without any further divergences from their co-clustered B. rapa accessions, thus indicating that the investigated B. juncea has a monophyletic maternal origin from cam-type B. rapa. Clade II comprises all the B. oleracea lines and other wild C-genome species, parallelly branched with Clade I. The branch, which comprises only the B. napus accessions with a same nap cytoplasmic type, is inserted in the middle of Clade II and separated certain C-genome wild relatives (B. insularis and B. villosa) from the remaining part, which contains all B. cretica, B. incana and the cultivated B. oleracea. Clade III comprises mainly B. nigra, B. carinata and B. maurorum accessions, indicating that the investigated B. carinata has a monophyletic maternal origin from B. nigra. The major cytoplasmic haplotype of B. nigra was designated as nigra-type cytoplasm. The wild species B. maurorum had been reported to be close to the B-genome species [32] and seems evolved earlier than all the remaining part in Clade III. The topological branches in this tree displayed a clear hierarchical pedigree, from Clade III to Clade I (Fig. 3). Taken together, different from B. juncea and B. caritana, B. napus was dispersedly distributed in the B. rapa and B. oleracea clusters, suggesting its multiple maternal origins from A-genome B. rapa or certain C-genome Brassica species (2n = 18).

Molecular phylogeny of Brassica genus. This tree was inferred using Maximum Likelihood method based on 42 entire chloroplast genomes from representative materials centering on Brassica genus. The front letters A, AC, AB, C, BC and B of the entry name stand for the AA-, AACC-, AABB-, CC-, BBCC- and BB- genome species B. rapa, B. napus, B. juncea, B. oleracea (and other C-genome species), B. carinata and B. nigra, respectively. The numbers displayed in the corresponding branching nodes are the bootstrap values (%) calculated from 500 trials, supporting the reliability of the obtained tree structure. The length of branches indicates the evolutionary divergence according to the scale bar (relative units) at the bottom. The input materials with diverse cytoplasmic haplotypes were labeled with cycles of corresponding colors, the separated clades constitute the whole evolutionary pedigree are marked on the right

The evolution of Brassica tightly associates with a set of its close genera

Intriguingly, Raphanus sativus was inserted between Clade II and Clade III and bidirectionally close to B. villosa and B. maurorum in the Brassica phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3), suggesting certain association between Raphanus genus and Brassica phylogeny. To explore whether any more other genus also mingle with Brassica genus, a phylogenetic tree containing 54 (Thirteen in and 41 beyond Brassica genus) chloroplast genome sequences in Brassicaceae family was constructed (Fig. 4). The tree displays an evolutionary pedigree with a clear hierarchical architecture. The Brassicaceae family was basically divided into two large lineages, containing Arabidopsis/Matthiola and Draba/Brassica genera, respectively, which is congruent with the previous studies [33, 34]. Another three materials, Eruca sativa, Moricandia arvensis and Sinapis arvensis, were also identified to be tightly integrated with the evolution of Brassica genus. Eruca sativa and Moricandia arvensis were located at the same positions as Raphanus sativus, while three herein sequenced and one public Sinapis arvensis (Sinapis-4) accessions displayed scattered distribution that is fully merged together with the B-genome containing species in Clade III. These findings imply a tight evolutionary association among Brassica and these relatives. Cakile arabica, Orychophragmus diffusus, Alliaria grandifolia, Isatis tinctona and Scherenkiella parvula in Clade IV were shown to be close to Brassica cluster at cytoplasmic DNA level. Successful germplasm development through inter-specific sexual or somatic hybridization between Brassica species with Orychophragmus violaceus or Isatis tinctona [35, 36] could partially support that the species in Clade IV are fairly close to Brassica.

Molecular phylogeny of Brassicaceae family. This tree was inferred using Maximum Likelihood method based on the entire chloroplast genomes from representative materials based on 54 chloroplast genomes. This tree was conducted and handled the same as it in Fig. 3. Sequence information for the chloroplast genomes of other cruciferous species are provided in Materials and Methods. Accessions representing the genera integrated into the phylogeny of Brassica genus are labeled with blue cycles, Accessions representing the genera close to Brassica genus are labeled with green cycles

Uncoupled inheritance of chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes in B. napus CMS lines

Mitochondrial genome represents another half set of cytoplasmic DNA. To ascertain how about the Brassica phylogeny if being inferred based on mitochondrial genomes, the segmented sequences containing the mitochondrial allelic variants from each corresponding material inside and around Brassica genus were extracted and concatenated as each separate intact sequence. All the assembled sequences were subjected to phylogenetic analysis according to the above same procedure used for chloroplast genomes. The obtained mitochondrial tree (Fig. 5) displayed a pedigree largely resembling the tree that was derived based on cpDNA (Fig. 3). Likewise, it also diverged into three clades, each of the natural Brassica materials possesses nearly identical evolutionary positions in both the cpDNA and mtDNA deriving trees, the same maternal origin relationships of the three Brassica allotetraploid crops were inferred. The location of four genera (Raphanus sativus, Eruca stivus, Moricandia arvensis and Sinapis arvensis) in the mtDNA derived tree were also integrated into Brassica genus, demonstrating that mtDNA evolved parallelly linked with cpDNA in Brassica genus. Nevertheless, differences happened for the B. napus cytoplasmic male sterile lines, i.e., mori [26, 27] and nsa [25] CMS lines, which have been successfully utilized in heterosis-driving hybrid breeding. Mori and nsa lines located in the cam-type and nap-type B. napus clusters, respectively, in the cpDNA deriving tree (Figure S5), and possess the identical natural cam-type and nap-type chloroplast sequences, respectively. However, they are clustered close to their mtDNA donor species in the mtDNA deriving tree (Fig. 5), i.e., the B. napus mori and nsa sterile line each clustered together with Moricandia arvensis and Sinapis arvensis, respectively. The coupled inheritance of mitochondrial genomes and chloroplast genomes in the B. napus CMS lines has been disturbed.

Estimation of divergence times of Brassica crops

The phylogenetic tree containing 54 chloroplast genome sequences in Brassicaceae family (Fig. 4) was subjected to estimate the divergence time for these investigated Brassica species, the timetree was conducted by Reltime [37]. It was calibrated referring to two previously estimated divergence times: 30–35 million years ago (Mya) which dated the speciation of genus Aethionema and 25–30 Mya which dated the separation of two large Brassicaceae clades including Arabidopsis and B. napus, respectively [33, 38]. Eucalyptus verrucata was set as the outgroup. The obtained timetree (Figure S7) indicated that Aethionema might be an ancient cruciferous genus and there were two major periods for species radiation in Brassicaceae family. During 25–18 Mya, certain genus emerged and separated from each other; and then during the second radiation period (15–6 Mya), most of the genus speciated and formed several large clades. Brassica genus emerged approximately at 4.85 Mya, and began maybe as a kind of B. nigra or B. rapa. Moricandia arvensis, Eruca stivus, Brassica maurorum, Raphanus sativus and Sinapis arvensis speciated at 3.15 Mya, 2.85 Mya, 2.17 Mya, 2.05 Mya and 1.42 Mya, respectively. The Brassica C-genome species (e.g., B. villosa and B. oleracea) separated from A-genome species (B. rapa) since 1.12 Mya. Three allotetraploid species (B. juncea, B. carinata and B. napus) speciated during the period 0.17–0.01 Mya or much later, which are consistent with the estimated originating time of ~ 7500 years ago for B. napus [4] and the cultivation beginning time of ~ 7000 years ago for B. juncea [7]. The Brassica tetraploid species are much younger than certain other polyploidy crops, e.g., the emerge of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) at 1–2 Mya [39, 40] and the emerge of soybean (Glycine max) at 0.8 Mya [41].

Discussion

The comparative genomics of cytoplasmic genomes provides insights into the Brassica phylogeny and the origin of nap- type B. napus

As mentioned above, B. rapa mainly contains a predominant haplotype (cam-type) and a newly identified sarson-type cytoplasm, which presents merely approximately 50 cpDNA and 20 mtDNA basic variations (Table S3). Fourteen B. juncea aceesions including different vegetable and oil varieties possess only one chloroplast and nearly one mitochondrial DNA haplotype almost identical to the corresponding B. rapa cam-type haplotype. B. carinata (BC2) clustered next to B. nigra. None cytoplasmic DNA types of BB-genome and CC-genome diploid species have ever been detected in the germplasm collections of the natural B. juncea or B. carinata, respectively. These results ascertain that B. juncea and B. carinata each has a monophyletic maternal origin from B. rapa and B. nigra, respectively.

Three major haplotypes were identified in our natural B. napus collection. Of the 24 sequenced B. napus accessions, 7 lines tightly clustered with the majority of B. rapa in Clade I (Fig. 3) and thus are recognized as cam-type. They contain nearly none cpDNA SNP differences from their co-clustering B. rapa and B. juncea materials (Table S3), indicating a direct maternal origin of these B. napus accessions from the cam-type B. rapa. Two previously known polima-type lines (Xiang5A and 20A) also clustered in Clade I but adjacent to sarson-type B. rapa (Sarson-1) with minor divergence, suggesting that the polima haplotype may inherit from certain sarson-type like B. rapa, which is different from the previous assumption that polima haplotype likely diverge from Cam haplotype. Nap-type cytoplasm, which is predominant with a population frequency of 87.1% in our B. napus collection, resides in numerous elite rapeseed cultivars worldwide (e.g., Darmor and ZS11). The cluster of nap-type B. napus is inserted in the middle of C-genome Clade II, appears like a separate haplotype that is parallel to B. cretica, B. incana, B. insularis, B. villosa and B. oleracea. This was also supported by our mtDNA-based phylogeny (Fig. 5), and also by the recent cpDNA-based phylogenetic studies that included other three more C-genome species: B. rupestris, B. montana and B. macrocarpa [9].

Since nap-type cytoplasm is highly divergent from the known cultivated C- genome materials, there is a great possibility that one certain C-genome wild species rather than B. oleracea may have donated the nap-type cytoplasm to B. napus, and also the corresponding nuclear C subgenome. Judging from the cytoplasmic inheritance, the current natural B. napus may have three maternal parents, two of A genome B. rapa and one of C genome species, possessing higher cytonuclear diversity than B. juncea and B. carinata. A refined model of U’s Triangle delineating the diffusion of cytoplasmic haplotypes in Brassica genus has been proposed in Fig. 6. Unexpectedly, the B. rapa variety broccoletto had been previously identified possessing identical nap- cpDNA haplotype [15, 18]. Whether broccoletto is the original female parent of nap-type B. napus yet need further evaluation. The investigated broccoletto accession collected from Italy were generally cultivated alongside multifarious wild Brassica species [18]. Whereupon, the presence of nap-type haplotype in these B. rapa accessions may result from as yet unidentified introgression events, i.e., the stepwise transfer of nap-type cytoplasm from B. napus into B. rapa through natural hybridization and consecutive backcrosses.

A refined model of U’s Triangle. Ellipses of single and double lines represent three basic diploid and three tetraploid species in Brassica genus. Diffusion of the corresponding cytoplasmic haplotypes were indicated by the arrows. Ellipse of dashed lines represents the close (diploid) species in other genera which can be used to create extensive germplasms with novel allotetraploid genomes and various cytonuclear combinations

Strong parallel evolution among Brassica and several relative genera

As clearly demonstrated in both the cpDNA and mtDNA based phylogenetic trees (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5), Raphanus sativus, Eruca sativa and Moricandia arvensis located between B. villosa and B. maurorum, namely between the B. oleracea wild relatives and B-genome species. Sinapis arvensis converged with the B-genome containing species in Clade IV (Fig. 3). These results suggest a potential co-originating (and co-evolving) relationships among Brassica and these relative genera. Comparative analysis of genomic framework using 22 genomic blocks (GB) demonstrated that most GB associations in Brassica species could be detected in Raphanus sativus [42], suggesting that Raphanus and Brassica species potentially shared a common hexaploid ancestor after whole genome triplication (WGT). Common translocation Proto-Calepineae Karyotype (tPCK)-like ancestors were deduced to be the likely common ancestor of all current Brassiceae species that had undergone WGT and repetitive chromosomal rearrangements. Phylogenetic analysis based on 32 mitochondrial protein-coding genes suggested that Eruca sativa is closer to the Brassica species and Raphanus sativus than to Arabidopsis thaliana [43]. The U’s Triangle theory were accordingly revisited and extended into a multi-vertex model [42], which should include not only Raphanus, but also Eruca, Moricandia and Sinapis species as basic diploid species as suggested herein by our studies (Fig. 6). Future determination of nuclear genomes of the representative Eruca, Moricandia and Sinapis species would provide detailed insights into the genomic and evolutionary association among these genera.

Heavy interspecific recombinations of mitochondrial genomes caused the coupled inheritance of both cytoplasmic genomes

Generally, mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes demonstrate consistent evolutionary relationships in higher plants, because of their coupled inheritance in a uniparental manner. The inconsistent locations of B. napus mori and nsa sterile lines, in the mtDNA and cpDNA based phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5 and S5) revealed their uncoupled inheritance of mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes. Mori sterile line (AC490) was primarily obtained by protoplast fusion between Moricandia arvensis (MM, 2n = 28) and B. juncea [26, 44], and then the CMS phenotype was transferred into B. napus through several rounds of sexual hybridization. Nsa sterile line (AC500) was developed primarily also from protoplast fusion between B. napus and Sinapis arvensis [25]. Sequencing analysis of Ogura sterile line, which was also developed through somatic hybridization of Raphanus sativus and B. napus [45, 46], revealed that rearrangement happened extensively in its mitochondrial genome [47]. Nine regions were identified to be unique to the all the published Brassica mitochondrial genome sequences belonging to U’s Triangle. Therefore, both the mori and nsa lines ought to contain plenty of mitochondrial genome regions from their incipient donor parents, thus clustered close to Moricandia arvensis and Sinapis arvensis, respectively, in the mtDNA based phylogenetic tree. It seems that somatic hybridization through protoplast fusion is an effective means to induce the recombination of mitochondrial genomes. Intergenomic recombinations and DNA rearrangements had been frequently identified within mitochondrial genomes [48, 49], suggesting that there must be a stronger variating dynamics in mitochondrial genomes than in chloroplast genomes.

While, it is notable that none recombination happened with the chloroplast genomes, since both the nsa and mori lines possess the identical nap- and cam-type chloroplast genomes from each of their recipient B. napus and B. juncea lines (Figure S5), respectively. This may result from lower interspecific recombination frequencies for cpDNA or strong artificial selection during the breeding process. Similarly, recombination of parental mitochondrial genomes rather than chloroplast DNA has been identified in a cybrid (cytoplasmic hybrids) obtained by protoplast fusion of Nicotiana tabacum and Hyoscyamus niger [50]. Thus, this phenomenon also would be potentially existent in other B. napus cybrid materials, e.g., the recent inap [51] CMS lines containing mtDNA components from Isatis indigotica. Collectively, these results indicated that recent human breeding activities have drastically disturbed the evolutionary accordance between cpDNA and mtDNA in a mass of cybrid lines.

Potential application of the Brassica cytoplasmic genetic resources

The diversified Brassica relatives stated above have been identified possessing desirable elite traits. Eruca sativa (2n = 22) is a diploid edible plant and its medicinal properties have various promoting effects to health [52]. Moricandia arvensis (2n = 28) is reported to be a C3-C4 intermediate species, transferring this feather of strong photosynthetic efficiency into Brassica crops have been tried by means of hybridization [53]. Sinapis arvensisis is a wild weedy plant of the genus Sinapis, both Sinapis arvensisis and Sinapis alba (2n = 24) possess high resistances to drought, leanness, multiple diseases, herbicides and pod shattering [54]. Certain Raphanus species were identified to be immune to clubroot [55]. The inter-specific evolutionary relationships (Fig. 6) of Brassica present a potential guidance for improving the current Brassica crops and even the development of certain novel allotetraploid gerplasms by intercrossing the corresponding diploid species.

Natural cytoplasmic variations could interact with nuclear genomes to shape a large proportion of phenotypic traits that contributed to adaptation [56]. The cytoplasmic genetic diversity in most of the current Brassica populations (e.g., B. juncea, B. carinata and cultivated B. oleracea) remain rather low, which may be a key limiting factor for crop improvment. To create extensive germplasms with various novel cytonuclear combinations may be of great significance for both the fundamental studies and the crop breeding in the future.

Conclusions

Compared with the huge nuclear genomes, cytoplasmic DNA is a primary and easy means to evaluate the evolutionary relationships. Meanwhile, it is also highly effective to dissect the maternal origins and to infer the primary originating events. Herein, the overall genetic diversity of Brassica cytoplasmic genomes has been systematically identified by the synchronous resequencing of the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes. The whole Brassica phylogeny has been refined and enriched, providing further insights into the understanding of the origin of the important B. napus nap-type cytoplasm. Human interference has remodeled the cytoplasmic inheritance in B. napus. The obtained genetic resources can substantially support the further research on the Brassica evolution, the development of novel germplasms.

Methods

Plant materials

A set of 480 worldwide B. napus accessions were collected from the National Mid-term Genebank for Oil Crops of China, it has been repeatedly used as a core rapeseed collection in our previous studies [57]. The B. rapa and B. juncea populations contain primarily landraces, which were collected across China. The cultivated B. oleracea inbred lines were obtained commercially from market, the wild B. oleracea and other C-genome wild species which are native to coastal southern and western Europe were collected from rocky Atlantic coasts of Spain (Bay of Biscay) and the Centre for Genetic Resources, The Netherlands (CGN). Detailed information in regard to all the above materials and other materials in Brassica genus and its relative genera are provided in Table S2. Plant materials were planted in the experimental fields or greenhouses of Oil Crops Research Institute of CAAS in Wuhan (114.31°E, 30.52°N), from October 2015 to May 2017. The collection, identification, reproduction and conservation were conducted by the Rapeseed Germplasm Team in our institute, under the long-term support of Chinese national projects regarding species conservation and germplasm development. All the plant materials investigated here were deposited as seeds in the National Mid-term Genebank for Oil Crops of China.

Genotyping analysis

Leaf total DNA of the corresponding accessions were directly extracted using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method described by Lutz et al., [58] and then subjected to genotyping analysis. High Resolution Melting (HRM) experiments were performed in 98/384-well plates using the Roche LightCycler 480® High Resolution Melting PCR Master Mix and analyzed by the LightCycler 480® Gene Scanning Software. Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP) analysis used for variant validation and haplotype dissection were performed using KASP Master mix according to the company’s protocols (LGC Genomics, Teddington, Middlesex, UK) on the Roche LightCycler 480® System.

Isolation of the cytoplasmic DNA

Isolation of the cytoplasmic DNA was performed according to Hao et al., [59] with minor modifications. The newly developed young leaves were picked from 5 to 10 representative plants of each accession, and then homogenized thoroughly by Dounce homogenizer in isolation buffer [25 mM MOPS-KOH, 0.4 M mannitol, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM tricine, 8 mM cysteine, 0.1% BSA (w/v) and 0.1% PVP-40 (w/v), pH 7.8]. One centrifugation step (300 g, 5 min) was performed to remove the unwanted whole plant cells and cell debris that mainly contain nuclear DNA contaminants. Another following centrifugation step (1500 g, 10 min) was added to remove a large proportion of chloroplasts to keep a proportionable ratio between cpDNA and mtDNA content. Then, the mixture of chloroplasts and mitochondria were collected by a further centrifugation step (20,000 g, 20 min) and then subjected to DNA isolation, using the CTAB method.

Sequencing, genome assembly, variant calling and validation

High-throughput sequencing of the cytoplasmic DNA was performed according to our previous study [16]. The DNA was randomly ultrasonically sheared and prepared into paired-end (PE) libraries with insert sizes ranging from 300 to 400 bp, and then subjected to an Illumina Hiseq2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) sequencing platform for sequencing at both single ends. Clean reads were directly mapped to a tandem sequence gather consisting of representative public cruciferous chloroplast genomes using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) MEM program [60] under default parameters. The mapped paired-end reads were extracted and de novo assembled using the SOAPdenovo software package [29]. The obtained contigs were located on the yet published Brassica chloroplast genomes through BLAST alignments, and then sutured by manually jointing the overlapping ends between each two contiguous contigs. Basic variants (SNP and short InDels) were called using standard BWA/Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) pipeline [30], the chloroplast and mitochondrion genomes of B. napus line 51,218 (GenBank: KP161617.1 and KP161618.1) were used as the cpDNA and mtDNA reference genomes, respectively.

Phylogenetic and molecular clock analysis

Chloroplast genome sequences were trimmed with aligned beginning sequences, and then subjected to alignment, which was conducted by ClustalW [61]. Maximum Likelihood trees were conducted by MEGA7 [62] based on Tamura-Nei substitution model. Timetree analysis was conducted using the RelTime method [37] based on original Newick formatted phylogenetic tree files, according to the guided procedure inplanted in MEGA7.

Availability of data and materials

The chloroplast and mitochondrial genome sequences of Brassica napus strain 51218 can be found in GenBank under KP161617.1 and KP161618.1, respectively. Information for the cruciferous cpDNA sequence gather and chloroplast genome sequences used in phylogenetic analysis can be found in Additional file 3. The obtained chloroplast genomes were provided in Additional file 3 and deposited at Mendeley Data (DOI: https://doi.org/10.17632/skfwfrwgjs.1).

Abbreviations

- cpDNA:

-

Chloroplast DNA

- mtDNA:

-

Mitochondrial DNA

- pol :

-

Polima

- CMS:

-

Cytoplasmic male sterility

- KASP:

-

Kompetitive allele specific PCR

References

Nagaharu U. Genome-analysis in Brassica with special reference to the experimental formation of B. napus and peculiar mode of fertilization. Japan J Bot. 1935;7:389–452.

Liu J, Hua W, Hu Z, Yang H, Zhang L, Li R, et al. Natural variation in ARF18 gene simultaneously affects seed weight and silique length in polyploid rapeseed. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E5123–32.

Wang X, Wang H, Wang J, Sun R, Wu J, Liu S, et al. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1035–9.

Chalhoub B, Denoeud F, Liu S, Parkin IA, Tang H, Wang X, et al. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science. 2014;345:950–3.

Liu S, Liu Y, Yang X, Tong C, Edwards D, Parkin IA, et al. The Brassica oleracea genome reveals the asymmetrical evolution of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3930.

Parkin IA, Koh C, Tang H, Robinson SJ, Kagale S, Clarke WE, et al. Transcriptome and methylome profiling reveals relics of genome dominance in the mesopolyploid Brassica oleracea. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R77.

Yang J, Liu D, Wang X, Ji C, Cheng F, Liu B, et al. The genome sequence of allopolyploid Brassica juncea and analysis of differential homoeolog gene expression influencing selection. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1225–32.

Lu K, Wei L, Li X, Wang Y, Wu J, Liu M, et al. Whole-genome resequencing reveals Brassica napus origin and genetic loci involved in its improvement. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1154.

An H, Qi X, Gaynor ML, Hao Y, Gebken SC, Mabry ME, et al. Transcriptome and organellar sequencing highlights the complex origin and diversification of allotetraploid Brassica napus. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2878.

Birky CW. The inheritance of genes in mitochondria and chloroplasts: Laws, mechanisms, and models. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:125–48.

Nikiforova SV, Cavalieri D, Velasco R, Goremykin V. Phylogenetic analysis of 47 chloroplast genomes clarifies the contribution of wild species to the domesticated apple maternal line. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:1751–60.

Gornicki P, Zhu H, Wang J, Challa GS, Zhang Z, Gill BS, et al. The chloroplast view of the evolution of polyploid wheat. New Phytol. 2014;204:704–14.

Carbonell-Caballero J, Alonso R, Ibañez V, Terol J, Talon M, Dopazo J. A phylogenetic analysis of 34 chloroplast genomes elucidates the relationships between wild and domestic species within the genus citrus. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:2015–35.

Daniell H, Lin CS, Yu M, Chang WJ. Chloroplast genomes: diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 2016;17:134.

Allender CJ, King GJ. Origins of the amphiploid species Brassica napus L investigated by chloroplast and nuclear molecular markers. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:54.

Qiao J, Cai M, Yan G, Wang N, Li F, Chen B, et al. High-throughput multiplex cpDNA resequencing clarifies the genetic diversity and genetic relationships among Brassica napus, Brassica rapa and Brassica oleracea. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14:409–18.

Kim CK, Seol YJ, Perumal S, Lee J, Waminal NE, Jayakodi M, et al. Re-exploration of U's triangle Brassica species based on chloroplast genomes and 45S nrDNA sequences. Sci Rep. 2018;8:7353.

Li P, Zhang S, Li F, Zhang S, Zhang H, Wang X, et al. A phylogenetic analysis of chloroplast genomes elucidates the relationships of the six economically important Brassica species comprising the triangle of U. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:111.

Chang S, Yang T, Du T, Huang Y, Chen J, Yan J, et al. Mitochondrial genome sequencing helps show the evolutionary mechanism of mitochondrial genome formation in Brassica. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:497.

Yang J, Liu G, Zhao N, Chen S, Liu D, Ma W, et al. Comparative mitochondrial genome analysis reveals the evolutionary rearrangement mechanism in Brassica. Plant Biol. 2016;18:527–36.

Yamagishi H, Bhat SR. Cytoplasmic male sterility in Brassicaceae crops. Breed Sci. 2014;64:38–47.

Liu J, Hao W, Liu J, Fan S, Zhao W, Deng L, et al. A novel chimeric mitochondrial gene confers cytoplasmic effects on seed oil content in polyploid rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Mol Plant. 2019;12:582–96.

Fu TD. Production and research of rapeseed in the people’ republic of China. Eucarpia Cruciferae News. 1981;6:6–7.

Handa H, Gualberto JM, Grienenberger JM. Characterization of the mitochondrial orfB gene and its derivative, orf224, a chimeric open reading frame specific to one mitochondrial genome of the "Polima" male-sterile cytoplasm in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Curr Genet. 1995;28:546–52.

Wei W, Li Y, Wang L, Liu S, Yan X, Mei D, et al. Development of a novel Sinapis arvensis disomic addition line in Brassica napus containing the restorer gene for Nsa CMS and improved resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and pod shattering. Theor Appl Genet. 2010;120:1089–97.

Prakash S, Kirti PB, Bhat SR, Gaikwad K, Kumar VD, Chopra VL. A Moricandia arvensis - based cytoplasmic male sterility and fertility restoration system in Brassica juncea. Theor Appl Genet. 1998;97:488–92.

Ashutosh KP, Dinesh Kumar V, Sharma PC, Prakash S, Bhat SR. A novel orf108 co-transcribed with the atpA gene is associated with cytoplasmic male sterility in Brassica juncea carrying Moricandia arvensis cytoplasm. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:284–9.

Shi C, Hu N, Huang H, Gao J, Zhao YJ, Gao LZ. An improved chloroplast DNA extraction procedure for whole plastid genome sequencing. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31468.

Luo R, Liu B, Xie Y, Li Z, Huang W, Yuan J, et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. Gigascience. 2012;1:18.

Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, Poplin R, Del Angel G, Levy-Moonshine A, et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the genome analysis toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2013;43:11.10.1–33.

Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:512–26.

Yao XC, Du XZ, Ge XH, Chen JP, Li ZY. Intra- and intergenomic chromosome pairings revealed by dual-color GISH in trigenomic hybrids of Brassica juncea and B carinata with B maurorum. Genome. 2010;53:14–22.

Hohmann N, Wolf EM, Lysak MA, Koch MA. A time-calibrated road map of Brassicaceae species radiation and evolutionary history. Plant Cell. 2015;27:2770–84.

Kagale S, Robinson SJ, Nixon J, Xiao R, Huebert T, Condie J, et al. Polyploid evolution of the Brassicaceae during the Cenozoic era. Plant Cell. 2014;26:2777–91.

Zhao ZG, Hu TT, Ge XH, Du XZ, Ding L, Li ZY. Production and characterization of intergeneric somatic hybrids between Brassica napus and Orychophragmus violaceus and their backcrossing progenies. Plant Cell Rep. 2018;27:1611–21.

Du XZ, Ge XH, Yao XC, Zhao ZG, Li ZY. Production and cytogenetic characterization of intertribal somatic hybrids between Brassica napus and Isatis indigotica and backcross progenies. Plant Cell Rep. 2009;28:1105–13.

Tamura K, Battistuzzi FU, Billing-Ross P, Murillo O, Filipski A, Kumar S. Estimating divergence times in large molecular phylogenies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:19333–8.

Huang CH, Sun R, Hu Y, Zeng L, Zhang N, Cai L, et al. Resolution of Brassicaceae phylogeny using nuclear genes uncovers nested radiations and supports convergent morphological evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:394–412.

Li F, Fan G, Lu C, Xiao G, Zou C, Kohel RJ, et al. Genome sequence of cultivated upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum TM-1) provides insights into genome evolution. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:524–30.

Zhang T, Hu Y, Jiang W, Fang L, Guan X, Chen J, et al. Sequencing of allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. acc. TM-1) provides a resource for fiber improvement. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:531–7.

Li YH, Zhou G, Ma J, Jiang W, Jin LG, Zhang Z, et al. De novo assembly of soybean wild relatives for pan-genome analysis of diversity and agronomic traits. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:1045–52.

Cheng F, Liang J, Cai C, Cai X, Wu J, Wang X. Genome sequencing supports a multi-vertex model for Brassiceae species. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017;36:79–87.

Wang Y, Chu P, Yang Q, Chang S, Chen J, Hu M, et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of Eruca sativa mill. (garden rocket). PLoS One. 2014;9:e105748.

Kirti PB, Narasimhulu SB, Prakash S, Chopra VL. Somatic hybridization between Brassica juncea and Moricandia arvensis by protoplast fusion. Plant Cell Rep. 1992;11:318–21.

Jourdan PS, Earle ED, Mutschler MA. Synthesis of male sterile, triazine-resistant Brassica napus by somatic hybridization between cytoplasmic male sterile B. oleracea and atrazine-resistant B. campestris. Theor Appl Genet. 1989;78:445–55.

Sakai T, Imamura J. Intergeneric transfer of cytoplasmic male sterility between Raphanus sativus (CMS line) and Brassica napus through cytoplast-protoplast fusion. Theor Appl Genet. 1990;80:421–7.

Wang J, Jiang J, Li X, Li A, Zhang Y, Guan R, et al. Complete sequence of heterogenous-composition mitochondrial genome (Brassica napus) and its exogenous source. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:675.

Goremykin VV, Salamini F, Velasco R, Viola R. Mitochondrial DNA of Vitis vinifera and the issue of rampant horizontal gene transfer. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:99–110.

Alverson AJ, Rice DW, Dickinson S, Barry K, Palmer JD. Origins and recombination of the bacterial-sized multichromosomal mitochondrial genome of cucumber. Plant Cell. 2011;23:2499–513.

Sanchez-Puerta MV, Zubko MK, Palmer JD. Homologous recombination and retention of a single form of most genes shape the highly chimeric mitochondrial genome of a cybrid plant. New Phytol. 2015;206:381–96.

Kang L, Li P, Wang A, Ge X, Li Z. A novel cytoplasmic male sterility in Brassica napus (inap CMS) with Carpelloid stamens via protoplast fusion with Chinese Woad. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:529.

Katsarou D, Omirou M, Liadaki K, Tsikou D, Delis C, Garagounis C, et al. Glucosinolate biosynthesis in Eruca sativa. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;109:452–66.

Tsutsui K, Jeong BH, Ito Y, Bang SW, Kaneko Y. Production and characterization of an alloplasmic and monosomic addition line of Brassica rapa carrying the cytoplasm and one chromosome of Moricandia arvensis. Breed Sci. 2011;61:373–9.

Jugulam M, Ziauddin A, So KK, Chen S, Hall JC. Transfer of Dicamba tolerance from Sinapis arvensis to Brassica napus via embryo rescue and recurrent backcross breeding. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141418.

Kamei A, Tsuro M, Kubo N, Hayashi T, Wang N, Fujimura T, et al. QTL mapping of clubroot resistance in radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2010;120:1021–7.

Roux F, Mary-Huard T, Barillot E, Wenes E, Botran L, Durand S, et al. Cytonuclear interactions affect adaptive traits of the annual plant Arabidopsis thaliana in the field. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:3687–92.

Li F, Chen B, Xu K, Wu J, Song W, Bancroft I, et al. Genome-wide association study dissects the genetic architecture of seed weight and seed quality in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). DNA Res. 2014;21:355–67.

Lutz KA, Wang W, Zdepski A, Michael TP. Isolation and analysis of high quality nuclear DNA with reduced organellar DNA for plant genome sequencing and resequencing. BMC Biotechnol. 2011;11:54.

Hao W, Fan S, Hua W, Wang H. Effective extraction and assembly methods for simultaneously obtaining plastid and mitochondrial genomes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108291.

Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60.

Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X Version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–48.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4.

Acknowledgements

We thank Donglian Wang and Hao Li for their skilled assistance with the field work.

Funding

This work was mainly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number: 31600179), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China (Grant Number: 2017CFB230) and Chinese Fundamental Research Funds for Central Non-profit Scientific Institution. It was also partially funded by the National Key Program for Research and Development of China (Grant Number: 2016YFD0100202) and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS). The funding agencies did not contribute to the conception of this study, collection of materials or generation, analysis, interpretation of the data or writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JQ conceived and designed the experiments. XZ and BC planted the materials, XZ, QH1 and JQ performed the genotyping analyses and extracted the cytoplasmic DNA. BC, KX and XW contributed to the phenotyping identification. QH2 provided the B. napus Nsa sterile materials. JQ and FH conducted the bioinformatic analyses. JQ analyzed the data, JQ and XZ wrote the manuscript, YH contributed to data interpretation and revised the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and contributed to this manuscript. The author (s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Figure S1.

Representative genotyping results by HRM analysis. (A) The normalized and temperature-shifted difference plot indicated that three site-specific haplotypes were identified in a plate of 96 plant DNA samples using HRM407 primers. (B) The normalized and temperature-shifted difference plot showed that two site-specific haplotypes were identified in a plate of 96 plant DNA samples using HRM727 primers. Figure S2. Representative genotyping results in a plate of 384 plant DNA samples by KASP analysis for primers mP1858 (A) and cP1225 (B). Figure S3. Phylogenetic tree of Brassica rapa. This tree structure was inferred using Maximum Likelihood method based on the entire chloroplast genomes from representative B. rapa materials. The sequence data for materials Zicaitai-1, Turnip-3 and Sarsons-1 from Li et al. (2017) were added. Figure S4. Phylogenetic tree of Brassica juncea. This tree structure was inferred using Maximum Likelihood method based on the entire chloroplast genomes from representative B. juncea materials. Figure S5. Phylogenetic tree of Brassica napus. This tree structure was inferred using Maximum Likelihood method based on the entire chloroplast genomes from representative B. napus materials. Figure S6. Phylogenetic tree of Brassica C-genome species. This tree structure was inferred using Maximum Likelihood method based on the entire chloroplast genomes from representative B. oleracea materials. Figure S7. Timetree analysis using the RelTime method. The timetree was computed based on the phylogenetic tree of Brassicaceae family in Fig. 4 using two calibration constraints labeled with blue stars and displayed only with topology. Eucalyptus verrucata labeled with lightgray was set as outgroup.

Additional file 2 Table S1

Primers used for HRM and KASP genotyping analysis. Table S2 List of plant materials investigated in this study. Table S3 Total cpDNA and mtDNA variant data.

Additional file 3 Appendix A

The dataset for chloroplast genome sequences of 72 Brassica accessions. Appendix B Accessions of the public sequence data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiao, J., Zhang, X., Chen, B. et al. Comparison of the cytoplastic genomes by resequencing: insights into the genetic diversity and the phylogeny of the agriculturally important genus Brassica. BMC Genomics 21, 480 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-06889-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-06889-0