Abstract

Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI) may arise both after sepsis and non-septic inflammatory conditions and is often associated with the release of fatty acids, including oleic acid (OA). Infusion of OA has been used extensively to mimic ALI. Recent research has revealed that intravenously administered recombinant human activated protein C (rhAPC) is able to counteract ALI. Our aim was to find out whether rhAPC dampens OA-induced ALI in sheep.

Methods

Twenty-two yearling sheep underwent instrumentation. After 2 days of recovery, animals were randomly assigned to one of three groups: (a) an OA+rhAPC group (n = 8) receiving OA 0.06 mL/kg infused over the course of 30 minutes in parallel with an intravenous infusion of rhAPC 24 mg/kg per hour over the course of 2 hours, (b) an OA group (n = 8) receiving OA as above, or (c) a sham-operated group (n = 6). After 2 hours, sheep were sacrificed. Hemodynamics was assessed by catheters in the pulmonary artery and the aorta, and extravascular lung water index (EVLWI) was determined with the single transpulmonary thermodilution technique. Gas exchange was evaluated at baseline and at cessation of the experiment. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance; a P value of less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

OA induced profound hypoxemia, increased right atrial and pulmonary artery pressures and EVLWI markedly, and decreased cardiac index. rhAPC counteracted the OA-induced changes in EVLWI and arterial oxygenation and reduced the OA-induced increments in right atrial and pulmonary artery pressures.

Conclusions

In ovine OA-induced lung injury, rhAPC dampens the increase in pulmonary artery pressure and counteracts the development of lung edema and the derangement of arterial oxygenation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mortality from acute lung injury (ALI) still remains between 30% and 40% [1]. Patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), the most severe form of ALI, present with elevated plasma concentrations of oleic acid (OA), which is one of the most abundantly occurring fatty acids in human plasma [2]. The proportion of OA increases in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with pneumonia and ARDS [3]. In combination with sepsis, an enhanced plasma level of OA adds to the risk of contracting ARDS [4]. However, independent of whether a high plasma concentration of OA contributes to ARDS or not, infusion of OA has been widely used to mimic non-septic lung injury in experimental settings. Administered to animals, OA increases pulmonary vascular pressure and permeability, resulting in the development of lung edema and arterial hypoxemia that are typical for this condition [5].

Activated protein C (APC) antagonizes thrombin generation by inactivating coagulation factors Va and VIIIa with protein S as a co-factor [6, 7]. It has been suggested that, by binding to endothelial APC receptor (EPCR) and to protease activated receptor-1 (PAR-1), APC initiates cytoprotective reactions, gene expression profile alterations, and anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects [8–11].

Recombinant human APC (rhAPC) increases survival from severe sepsis [12]. Reportedly, patients receiving rhAPC demonstrate a shorter duration of respiratory failure [13]. Protein C decreases markedly in patients with ALI, whether of septic or non-septic origin, and a low plasma level of protein C is associated with a poor clinical outcome [14, 15]. We speculated that rhAPC could be of potential benefit in the treatment of ALI. Recent studies of ovine sepsis or endotoxin-induced ALI support this assumption [16–18], whereas others have failed to demonstrate favorable effects either in animal [19–21] or human [22] studies. Up to now, no one study has documented beneficial effects of APC on models of non-septic ALI. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether intravenously administered rhAPC alleviates ovine OA-induced lung injury, assessing changes in pulmonary hemodynamics, extravascular lung water, and arterial oxygenation.

Materials and methods

The Norwegian Experimental Animal Board approved the study according to the rules and regulations of the Helsinki Convention for Use and Care of Animals.

Animal instrumentation

Twenty-two yearling sheep weighing 34.3 ± 7.5 kg (mean ± standard deviation) were instrumented under general anesthesia and treated postoperatively as described previously by our group [23]. In brief, an 8.5-Fr introducer (CC-350B; Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA) was inserted percutaneously in the left external jugular vein and a 5-Fr introducer (CP-07511-P; Arrow International, Inc., Reading, PA, USA) was inserted into the ipsilateral common carotid artery. After 1 to 3 days of recovery, the sheep were placed in an experimental pen. A flow-directed thermal dilution catheter (131HF7; Baxter) was introduced into the pulmonary artery, and a 4-Fr thermistor catheter (PV2014L16; Pulsion Medical Systems, München, Germany) was introduced into the thoracic aorta. The catheters were connected to pressure transducers (Transpac®III; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, North Chicago, IL, USA) and PV8115 (Pulsion Medical Systems).

Measurements and samples

Measurements were performed at 1-hour intervals. Mean pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP), pulmonary arterial occlusion pressure (PAOP), and mean right atrial pressure (RAP) were recorded on a Gould Polygraph 6600 (Gould Instruments, Cleveland, OH, USA). The pulmonary capillary micro-occlusion pressure (Pmo) was determined as described previously [24].

Heart rate (HR), mean systemic arterial pressure (MAP), cardiac index (CI), systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI), extravascular lung water index (EVLWI), and blood temperature were determined using a PiCCO plus monitor (Pulsion Medical Systems), where EVLWI is calculated using the transpulmonary thermodilution technique. Every value was calculated as a mean of three measurements, each consisting of a 10-mL bolus of ice-cold saline injected into the right atrium randomly during the respiratory cycle.

Left ventricular stroke work index (LVSWI) was calculated as LVSWI = 0.0136 × (MAP - PAOP) × CI/HR, and right ventricular stroke work index (RVSWI) was calculated as RVSWI = 0.0136 × (PAP - RAP) × CI/HR. Stroke volume index and pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI) were calculated using standard formulas.

Blood samples were drawn from the systemic (a) and the pulmonary artery (v) lines and analyzed for blood gases and hemoglobin (Rapid 860; Chiron Diagnostics Corporation, East Walpole, MA, USA) at the beginning and the end of the 2-hour experiment. Assuming the hemoglobin oxygen binding capacity to be 1.34 mL/g, oxygen delivery index (DO2I), oxygen consumption index (VO2I), venous admixture (Qs/Qt), and the alveolar-arterial oxygen tension difference (AaPO2) were calculated as described previously [23].

Experimental protocol

After 2 days of recovery, animals were randomly assigned to one of three groups: an OA+rhAPC group (n = 8) receiving OA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) 0.06 mL/kg infused over the course of 30 minutes in parallel with an intravenous infusion of rhAPC (Xigris®; Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA) 24 μg/kg per hour during the whole 2-hour experiment, an OA group (n = 8) receiving OA as above, or a group of sham-operated animals (n = 6). All sheep received a continuous infusion of isotonic saline at 5 mL/kg per hour. After completion of the experiment, the sheep were killed with an intravenous injection of thiopental sodium (Abbott) 100 mg/kg followed by 50 mmol KCl (B. Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean and analyzed by two-factor analysis of variance for repeated measurements. If F was statistically significant, Scheffe's test was applied for post hoc analysis of the changes in time. Comparison between OA and OA+rhAPC groups was evaluated at baseline (0 hours) and after 2 hours, applying the t test or the Mann-Whitney test when appropriate (SPSS 15.0 for Windows; LEAD Technologies, Charlotte, NC, USA). We regarded P values of less than 0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

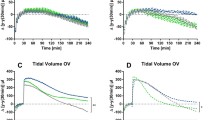

All of the sheep survived the instrumentation and the experiment without complications. Infusion of OA induced increments in EVLWI, PAP, and RAP that all declined significantly during infusion of rhAPC (Figure 1). Moreover, MAP and SVRI increased significantly (by 8% and 38%, respectively) with a concomitant 25% decrease in CI, but none of these variables was significantly influenced by rhAPC (Table 1). As the only variable, PVRI differed between the groups at baseline (P < 0.05). Administration of rhAPC tended to reduce the OA-induced increase in PVRI (Table 1), albeit without reaching statistical difference (P = 0.07). As shown in Table 1, the OA-induced changes in PAOP, Pmo, and RVSWI remained unaffected by rhAPC. We noticed no significant changes in LVSWI upon infusion of OA.

Changes in pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), right atrial pressure (RAP), and extravascular lung water index (EVLWI) in awake instrumented sheep subjected to intravenous bolus injection of oleic acid (OA) and co-administration of recombinant human activated protein C (rhAPC). In the figure, OA refers to the oleic acid-alone group (n = 8), OA+rhAPC refers to the rhAPC-treated OA group (n = 8), and sham refers to sham-operated animals (n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05 between OA and OA+rhAPC groups; †P < 0.05 from t = 0 hours in the OA group; ‡P < 0.05 from t = 0 hours in the OA+rhAPC group.

Oxygenation variables, including partial tension of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) and mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2), declined and AaPO2 increased after infusion of OA but improved significantly in animals exposed to rhAPC (Figure 2 and Table 2). The OA-induced increase in Qs/Qt (P < 0.05) (Table 2) tended to be reduced under exposure to rhAPC (P = 0.08) in parallel with increases in arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) and pH (P = 0.08 and 0.06, respectively), albeit without reaching significant intergroup differences. We noticed no effect of OA on partial tension of carbon dioxide in arterial blood (PaCO2), blood temperature, and hemoglobin concentration, and rhAPC did not influence any of these variables (Table 2). In both groups exposed to OA, we noticed a decline in DO2 in comparison with baseline whereas an intragroup decrease in VO2 was observed only in the rhAPC-treated animals, but with no significant intergroup difference (Table 2).

Changes in arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) and mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) in awake instrumented sheep subjected to intravenous bolus injection of oleic acid (OA) and co-administration of recombinant human activated protein C (rhAPC). In the figure, OA refers to the oleic acid-alone group (n = 8), OA+rhAPC refers to the rhAPC-treated OA group (n = 8), and sham refers to sham-operated animals (n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05 between OA and OA+rhAPC groups; †P < 0.05 from t = 0 hours in the OA group.

Discussion

The present investigation has shown that simultaneous administration of rhAPC ameliorates OA-induced lung injury. The rise in pulmonary artery pressure, the evolvement of lung edema, and the derangement of arterial oxygenation subsequent to intravenous bolus infusion of OA all improved significantly during co-administration of rhAPC in our ovine model of ALI.

The lung injury that we observed after infusion of OA had the same characteristics as noticed in several previous studies of this agent on larger animals, including sheep [5]. The cardiovascular instability (including the decrease in CI and the increments in pulmonary vascular pressure and RAP), the evolvement of pulmonary edema, and the reduction of arterial and mixed venous oxygenation subsequent to administration of OA are consistent with previous reports of this type of lung injury [25]. In animals exposed to rhAPC as co-treatment, the OA-induced increments in PAP and RAP decreased and PaO2 increased significantly. Similar observations have been made under exposure to rhAPC in other models of lung injury in sheep [16–18]. The nearly 30% decrease in oxygen delivery was caused mainly by a combined decline in SaO2 and CI with OA alone and almost solely by a decrease in CI in the OA+rhAPC group (Tables 1 and 2).

Our findings agree with recently reported effects of rhAPC in other ovine models of ALI [16–18]. In these studies, the animals had been exposed to combined smoke inhalation and airway instillation of live bacteria [16], feces into the peritoneum [17], or intravenously infused endotoxin [18]. All three of the investigations demonstrated improved arterial oxygenation and dampened pulmonary hypertension in animals treated with rhAPC. However, only sheep subjected to peritoneal sepsis or endotoxin infusion presented with reduced extravascular lung water [17, 18]. In contrast, Richard and colleagues [20], studying OA-induced lung injury in anesthetized mechanically ventilated pigs, found no beneficial effects of rhAPC given as pretreatment. In that study, pulmonary hemodynamics and arterial oxygenation deteriorated and plasma concentrations of IL-6 and IL-8 increased in animals subjected to infusion of rhAPC. However, our sheep had more pronounced hypoxemia as compared with their pig model. In addition, we suspect that the timing of APC pretreatment might have played a role in the outcome of the study. Possibly, the anticoagulant effects of APC could be a disadvantage before the onset of ALI. This suggestion is supported by investigators who found increased lung edema formation in rats subjected to intratracheal instillation of live Pseudomonas aeruginosa and co-administration of rhAPC [21]. These authors speculate that initial fibrin deposition might have sealed off the lung vasculature of non-treated animals, thereby reducing endothelial leakage.

Determination of EVLWI by means of the transpulmonary thermodilution technique is still debated. Our group and others have compared transpulmonary thermodilution with both the thermo-dye dilution technique and postmortem gravimetry and demonstrated close correlations [26–28].

The mechanism by which APC improves OA-induced lung injury is puzzling. Experimental studies have demonstrated that neutrophils rapidly enter the pulmonary parenchyma after initiation of ALI via different mechanisms, such as hypovolemic shock [29], intestinal ischemia/reperfusion [30], or administration of endotoxin [29, 31]. Thus, pulmonary neutrophil infiltration seems to be an important contributor to lung inflammation of various etiologies [32]. Inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis and monocyte production of pro-inflammatory cytokines have been proposed to contribute to the beneficial effects of APC in sepsis and ALI [18, 33–36]. However, in OA-induced ALI, neutrophil depletion does not seem to significantly affect the course of injury [37]. Early investigators noticed that OA triggers permeability edema in isolated dog lungs to which the perfusate had been depleted of blood components [38]. Therefore, most likely, the protective effects of APC on OA-induced lung injury result from intervention on other inflammatory pathways. It has been demonstrated that OA activates both the endothelin [39] and the eicosanoid pathways, including increased secretory phospholipase A2 [40] and thromboxane A2 [41–44]. Moreover, in vitro studies have revealed that APC causes a dose-dependent inhibition of interferon-induced expression of phospholipase A2 [45] and upregulation of cyclooxygenase II expression in endothelial cells [46]. OA may also promote ALI by increasing the ratio between angiotensin-converting enzymes I and II [47], upregulating inducible nitric-oxide synthase (iNOS), and inhibiting alveolar epithelial Na,K-ATPase activity [48]. In rats subjected to cecal ligation and puncture, the investigators found that depletion of protein C was associated with lung injury, upregulation of iNOS, and angiotensin-converting enzyme I/II ratio, all changes that were antagonized by administration of APC [49].

When the results of this study are evaluated, some limitations must be taken into account. First, hemodynamic and volumetric monitoring in animals subjected to respiratory distress is particularly challenging awake and may have contributed to the relatively large variations we noticed in some of the parameters. Second, in other ovine studies of sepsis or endotoxemia [16–18], effects appeared 4 to 6 hours after starting the infusion of rhAPC, so we cannot exclude the possibility that the observation time was too short for some variables to display significant intergroup differences. The reason for not prolonging the experiments beyond 2 hours was that most variables changed maximally within 1 hour and then declined to reach baseline after 3 to 4 hours. Third, there is a possibility that the study was too underpowered to show differences in all variables as early as at 2 hours. Thus, Qs/Qt, SaO2, oxygen extraction ratio (O2ER), pH, HR, Pmo, and PVRI all tended to improve in sheep receiving rhAPC (P = 0.06 to 0.08) alone, although without reaching statistical significance. As far as PVRI is concerned, lack of effect of rhAPC eventually could be caused by a significantly higher value at baseline compared with OA alone (Table 1). When we designed the study, we had no information about effects of rhAPC on this particular lung injury model which could be used in a power analysis of sample sizes. However, by using the present data, a retrospective analysis revealed that all of the latter variables could be expected to change significantly at a power of 80% with 10 animals in each group, but animal welfare and ethical reasons motivated us to keep the experimental groups as small as possible.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that rhAPC administered as co-treatment ameliorates ovine OA-induced lung injury by reducing pulmonary edema and improving oxygenation and pulmonary hemodynamics. However, further studies are warranted to elucidate the mechanisms by which APC counteracts the OA-induced lung injury.

Key messages

-

In ovine oleic acid-induced lung injury, recombinant human activated protein C (rhAPC) ameliorates the increments in pulmonary artery pressure and right atrial pressure.

-

rhAPC antagonizes the enhanced extravascular lung water and the derangement in arterial oxygenation.

Abbreviations

- AaPO2:

-

alveolar-arterial oxygen tension difference

- ALI:

-

acute lung injury

- APC:

-

activated protein C

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CI:

-

cardiac index

- EVLWI:

-

extravascular lung water index

- HR:

-

heart rate

- IL:

-

interleukin

- iNOS:

-

inducible nitric-oxide synthase

- LVSWI:

-

left ventricular stroke work index

- MAP:

-

mean systemic arterial pressure

- OA:

-

oleic acid

- PaO2:

-

partial tension of oxygen in arterial blood

- PAOP:

-

pulmonary arterial occlusion pressure

- PAP:

-

pulmonary arterial pressure

- Pmo:

-

pulmonary capillary micro-occlusion pressure

- PVRI:

-

pulmonary vascular resistance index

- Qs/Qt:

-

venous admixture

- RAP:

-

right atrial pressure

- rhAPC:

-

recombinant human activated protein C

- RVSWI:

-

right ventricular stroke work index

- SaO2:

-

arterial oxygen saturation

- SVRI:

-

systemic vascular resistance index.

References

Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000, 342: 1301-1308. 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801.

Quinlan GJ, Lamb NJ, Evans TW, Gutteridge JM: Plasma fatty acid changes and increased lipid peroxidation in patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1996, 24: 241-246. 10.1097/00003246-199602000-00010.

Baughman RP, Stein E, MacGee J, Rashkin M, Sahebjami H: Changes in fatty acids in phospholipids of the bronchoalveolar fluid in bacterial pneumonia and in adult respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Chem. 1984, 30: 521-523.

Bursten SL, Federighi DA, Parsons P, Harris WE, Abraham E, Moore EE, Moore FA, Bianco JA, Singer JW, Repine JE: An increase in serum C18 unsaturated free fatty acids as a predictor of the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1996, 24: 1129-1136. 10.1097/00003246-199607000-00011.

Schuster DP: ARDS: clinical lessons from the oleic acid model of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994, 149: 245-260.

Fulcher CA, Gardiner JE, Griffin JH, Zimmerman TS: Proteolytic inactivation of human factor VIII procoagulant protein by activated human protein C and its analogy with factor V. Blood. 1984, 63: 486-489.

Walker FJ, Sexton PW, Esmon CT: The inhibition of blood coagulation by activated Protein C through the selective inactivation of activated Factor V. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979, 571: 333-342.

Bilbault P, Lavaux T, Launoy A, Gaub MP, Meyer N, Oudet P, Pottecher T, Jaeger A, Schneider F: Influence of drotrecogin alpha (activated) infusion on the variation of Bax/Bcl-2 and Bax/Bcl-xl ratios in circulating mononuclear cells: a cohort study in septic shock patients. Crit Care Med. 2007, 35: 69-75. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000251133.26979.F4.

Feistritzer C, Riewald M: Endothelial barrier protection by activated protein C through PAR1-dependent sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 crossactivation. Blood. 2005, 105: 3178-3184. 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3985.

Shires GT, Fisher O, Murphy P, Williams S, Barber A, Johnson G, Davis B, Pahulu S: Recombinant activated protein C induces dose-dependent changes in inflammatory mediators, tissue damage, and apoptosis in in vivo rat model of sepsis. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2007, 8: 377-386. 10.1089/sur.2006.082.

White B, Schmidt M, Murphy C, Livingstone W, O'Toole D, Lawler M, O'Neill L, Kelleher D, Schwarz HP, Smith OP: Activated protein C inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced nuclear translocation of nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) production in the THP-1 monocytic cell line. Br J Haematol. 2000, 110: 130-134. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02128.x.

Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, LaRosa SP, Dhainaut JF, Lopez-Rodriguez A, Steingrub JS, Garber GE, Helterbrand JD, Ely EW, Fisher CJ: Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001, 344: 699-709. 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001.

Dhainaut JF, Laterre PF, Janes JM, Bernard GR, Artigas A, Bakker J, Riess H, Basson BR, Charpentier J, Utterback BG, Vincent JL: Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in the treatment of severe sepsis patients with multiple-organ dysfunction: data from the PROWESS trial. Intensive Care Med. 2003, 29: 894-903.

Shorr AF, Bernard GR, Dhainaut JF, Russell JR, Macias WL, Nelson DR, Sundin DP: Protein C concentrations in severe sepsis: an early directional change in plasma levels predicts outcome. Crit Care. 2006, 10: R92-10.1186/cc4946.

Matthay MA, Ware LB: Plasma protein C levels in patients with acute lung injury: prognostic significance. Crit Care Med. 2004, 32: S229-S232. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000126121.56990.D3.

Maybauer MO, Maybauer DM, Fraser JF, Traber LD, Westphal M, Enkhbaatar P, Cox RA, Huda R, Hawkins HK, Morita N, Murakami K, Mizutani A, Herndon DN, Traber DL: Recombinant human activated protein C improves pulmonary function in ovine acute lung injury resulting from smoke inhalation and sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2006, 34: 2432-2438. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000230384.61350.FA.

Wang Z, Su F, Rogiers P, Vincent JL: Beneficial effects of recombinant human activated protein C in a ewe model of septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2007, 35: 2594-2600.

Waerhaug K, Kuklin VN, Kirov MY, Sovershaev MA, Langbakk B, Ingebretsen OC, Ytrehus K, Bjertnaes LJ: Recombinant human activated protein C attenuates endotoxin-induced lung injury in awake sheep. Crit Care. 2008, 12: R104-10.1186/cc6985.

Nielsen JS, Larsson A, Rix T, Nyboe R, Gjedsted J, Krog J, Ledet T, Tonnesen E: The effect of activated protein C on plasma cytokine levels in a porcine model of acute endotoxemia. Intensive Care Med. 2007, 33: 1085-1093. 10.1007/s00134-007-0631-1.

Richard JC, Bregeon F, Leray V, Le Bars D, Costes N, Tourvieille C, Lavenne F, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Gimenez G, Guerin C: Effect of activated protein C on pulmonary blood flow and cytokine production in experimental acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med. 2007, 33: 2199-2206. 10.1007/s00134-007-0782-0.

Robriquet L, Collet F, Tournoys A, Prangère T, Nevière R, Fourrier F, Guery BP: Intravenous administration of activated protein C in Pseudomonas-induced lung injury: impact on lung fluid balance and the inflammatory response. Respir Res. 2006, 7: 41-10.1186/1465-9921-7-41.

Liu KD, Levitt J, Zhuo H, Kallet RH, Brady S, Steingrub J, Tidswell M, Siegel MD, Soto G, Peterson MW, Chesnutt MS, Phillips C, Weinacker A, Thompson BT, Eisner MD, Matthay MA: Randomized clinical trial of activated protein C for the treatment of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008, 178: 618-623. 10.1164/rccm.200803-419OC.

Kuklin VN, Kirov MY, Evgenov OV, Sovershaev MA, Sjoberg J, Kirova SS, Bjertnaes LJ: Novel endothelin receptor antagonist attenuates endotoxin-induced lung injury in sheep. Crit Care Med. 2004, 32: 766-773. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000114575.08269.F6.

Bjertnaes LJ, Koizumi T, Newman JH: Inhaled nitric oxide reduces lung fluid filtration after endotoxin in awake sheep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998, 158: 1416-1423.

Neumann P, Hedenstierna G: Ventilation-perfusion distributions in different porcine lung injury models. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001, 45: 78-86. 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.450113.x.

Sakka SG, Ruhl CC, Pfeiffer UJ, Beale R, McLuckie A, Reinhart K, Meier-Hellmann A: Assessment of cardiac preload and extravascular lung water by single transpulmonary thermodilution. Intensive Care Med. 2000, 26: 180-187. 10.1007/s001340050043.

Kirov MY, Kuzkov VV, Kuklin VN, Waerhaug K, Bjertnaes LJ: Extravascular lung water assessed by transpulmonary single thermodilution and postmortem gravimetry in sheep. Crit Care. 2004, 8: R451-10.1186/cc2974.

Katzenelson R, Perel A, Berkenstadt H, Preisman S, Kogan S, Sternik L, Segal E: Accuracy of transpulmonary thermodilution versus gravimetric measurement of extravascular lung water. Crit Care Med. 2004, 32: 1550-1554. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000130995.18334.8B.

Abraham E, Carmody A, Shenkar R, Arcaroli J: Neutrophils as early immunologic effectors in hemorrhage- or endotoxemia-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000, 279: L1137-L1145.

Terada LS, Dormish JJ, Shanley PF, Leff JA, Anderson BO, Repine JE: Circulating xanthine oxidase mediates lung neutrophil sequestration after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol. 1992, 263: L394-L401.

Nill MR, Oberyszyn TM, Ross MS, Oberyszyn AS, Robertson FM: Temporal sequence of pulmonary cytokine gene expression in response to endotoxin in C3H/HeN endotoxin-sensitive and C3H/HeJ endotoxin-resistant mice. J Leukoc Biol. 1995, 58: 563-574.

Abraham E: Neutrophils and acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2003, 31: S195-S199. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057843.47705.E8.

Brueckmann M, Hoffmann U, De Rossi L, Weiler HM, Liebe V, Lang S, Kaden JJ, Borggrefe M, Haase KK, Huhle G: Activated protein C inhibits the release of macrophage inflammatory protein-1-alpha from THP-1 cells and from human monocytes. Cytokine. 2004, 26: 106-113. 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.01.004.

Nick JA, Coldren CD, Geraci MW, Poch KR, Fouty BW, O'Brien J, Gruber M, Zarini S, Murphy RC, Kuhn K, Richter D, Kast KR, Abraham E: Recombinant human activated protein C reduces human endotoxin-induced pulmonary inflammation via inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis. Blood. 2004, 104: 3878-3885. 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2140.

Stephenson DA, Toltl LJ, Beaudin S, Liaw PC: Modulation of monocyte function by activated protein C, a natural anticoagulant. J Immunol. 2006, 177: 2115-2122.

Sturn DH, Kaneider NC, Feistritzer C, Djanani A, Fukudome K, Wiedermann CJ: Expression and function of the endothelial protein C receptor in human neutrophils. Blood. 2003, 102: 1499-1505. 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3880.

Hill LL, Chen DL, Kozlowski J, Schuster DP: Neutrophils and neutrophil products do not mediate pulmonary hemodynamic effects of endotoxin on oleic acid-induced lung injury. Anesth Analg. 2004, 98: 452-457. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000097167.39112.A3. table

Hofman WF, Ehrhart IC: Permeability edema in dog lung depleted of blood components. J Appl Physiol. 1984, 57: 147-153.

Wang L, Zhu DM, Su X, Bai CX, Ware LB, Matthay MA: Acute cardiopulmonary effects of a dual-endothelin receptor antagonist on oleic acid-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in dogs. Exp Lung Res. 2004, 30: 31-42.

Furue S, Kuwabara K, Mikawa K, Nishina K, Shiga M, Maekawa N, Ueno M, Chikazawa Y, Ono T, Hori Y, Matsukawa A, Yoshinaga M, Obara H: Crucial role of group IIA phospholipase A(2) in oleic acid-induced acute lung injury in rabbits. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999, 160: 1292-1302.

Goff CD, Corbin RS, Theiss SD, Frierson HF, Cephas GA, Tribble CG, Kron IL, Young JS: Postinjury thromboxane receptor blockade ameliorates acute lung injury. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997, 64: 826-829. 10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00490-6.

Ishitsuka Y, Moriuchi H, Hatamoto K, Yang C, Takase J, Golbidi S, Irikura M, Irie T: Involvement of thromboxane A2 (TXA2) in the early stages of oleic acid-induced lung injury and the preventive effect of ozagrel, a TXA2 synthase inhibitor, in guinea-pigs. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2004, 56: 513-520. 10.1211/0022357023150.

Rostagno C, Gensini GF, Boncinelli S, Marsili M, Castellani S, Lorenzi P, Merciai V, Linden M, Chelucci GL, Cresci F: The prominent role of thromboxane A2 formation on early pulmonary hypertension induced by oleic acid administration in sheep. Thromb Res. 1990, 58: 35-45. 10.1016/0049-3848(90)90241-4.

Thies SD, Corbin RS, Goff CD, Binns OA, Buchanan SA, Shockey KS, Frierson HF, Young JS, Tribble CG, Kron IL: Thromboxane receptor blockade improves oxygenation in an experimental model of acute lung injury. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996, 61: 1453-1457. 10.1016/0003-4975(96)00077-X.

Menschikowski M, Hagelgans A, Hempel U, Lattke P, Ismailov I, Siegert G: On interaction of activated protein C with human aortic smooth muscle cells attenuating the secretory group IIA phospholipase A(2) expression. Thromb Res. 2008, 122: 69-76. 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.08.015.

Brueckmann M, Horn S, Lang S, Fukudome K, Schulze NA, Hoffmann U, Kaden JJ, Borggrefe M, Haase KK, Huhle G: Recombinant human activated protein C upregulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression in endothelial cells via binding to endothelial cell protein C receptor and activation of protease-activated receptor-1. Thromb Haemost. 2005, 93: 743-750.

He X, Han B, Mura M, Xia S, Wang S, Ma T, Liu M, Liu Z: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor captopril prevents oleic acid-induced severe acute lung injury in rats. Shock. 2007, 28: 106-111. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3180310f3a.

Vadasz I, Morty RE, Kohstall MG, Olschewski A, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Ghofrani HA: Oleic acid inhibits alveolar fluid reabsorption: a role in acute respiratory distress syndrome?. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005, 171: 469-479. 10.1164/rccm.200407-954OC.

Richardson MA, Gupta A, O'Brien LA, Berg DT, Gerlitz B, Syed S, Sharma GR, Cramer MS, Heuer JG, Galbreath EJ, Grinnell BW: Treatment of sepsis-induced acquired protein C deficiency reverses Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 inhibition and decreases pulmonary inflammatory response. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008, 325: 17-26. 10.1124/jpet.107.130609.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

This study was supported by Helse Nord (project number 4001.721.477), the departments of anesthesiology of University Hospital of North Norway and the Institute of Clinical Medicine of the University of Tromsø (Tromsø, Norway), and in part by Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA). The support from Eli Lilly and Company was limited to free use of rhAPC (Xigris®) in the study. MYK is a member of the Advisory Board of Pulsion Medical Systems (München, Germany). The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KW participated in the experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. MYK, VVK, and VNK participated in the design of the study and in the experiments. LJB participated in the administration and design of the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Waerhaug, K., Kirov, M.Y., Kuzkov, V.V. et al. Recombinant human activated protein C ameliorates oleic acid-induced lung injury in awake sheep. Crit Care 12, R146 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc7128

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc7128