Abstract

Introduction

Both patient- and context-specific factors may explain the conflicting evidence regarding glucose control in critically ill patients. Blood glucose variability appears to correlate with mortality, but this variability may be an indicator of disease severity, rather than an independent predictor of mortality. We assessed blood glucose coefficient of variation as an independent predictor of mortality in the critically ill.

Methods

We used eProtocol-Insulin, an electronic protocol for managing intravenous insulin with explicit rules, high clinician compliance, and reproducibility. We studied critically ill patients from eight hospitals, excluding patients with diabetic ketoacidosis and patients supported with eProtocol-insulin for < 24 hours or with < 10 glucose measurements. Our primary clinical outcome was 30-day all-cause mortality. We performed multivariable logistic regression, with covariates of age, gender, glucose coefficient of variation (standard deviation/mean), Charlson comorbidity score, acute physiology score, presence of diabetes, and occurrence of hypoglycemia < 60 mg/dL.

Results

We studied 6101 critically ill adults. Coefficient of variation was independently associated with 30-day mortality (odds ratio 1.23 for every 10% increase, P < 0.001), even after adjustment for hypoglycemia, age, disease severity, and comorbidities. The association was higher in non-diabetics (OR = 1.37, P < 0.001) than in diabetics (OR 1.15, P = 0.001).

Conclusions

Blood glucose variability is associated with mortality and is independent of hypoglycemia, disease severity, and comorbidities. Future studies should evaluate blood glucose variability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The optimal management of blood glucose in the ICU remains unclear. A study of surgical ICU patients in Leuven, Belgium, demonstrated that insulin therapy aimed at achieving blood glucose between 80 and 110 mg/dL (tight glucose control) decreased subject mortality compared to conventional treatment (maintenance of blood glucose between 180 and 200 mg/dL) [1]. Subsequent studies evaluating the role of insulin therapy in the ICU either failed to confirm these results, or were terminated early due to high hypoglycemia rates [2–6]. The largest prospective multicenter trial to date (Normoglycaemia in Intensive Care Evaluation and Survival Using Glucose Algorithm Regulation, NICE-SUGAR) reported an increase in 90-day mortality for the group with an 80 to 110 mg/dL blood glucose target when compared to a target of <180 mg/dL [7]. Despite continued uncertainty in glucose management, professional societies currently recommend moderate glucose control for all critically ill adult patients [8, 9].

One explanation for the incongruencies between studies is that mean blood glucose (reported most often in relation to blood glucose target) may not be the most important aspect of glucose control in critically ill patients. Some authors postulate that other glucose metrics, including within-patient glycemic variability, may be as important, or more important than a mean blood glucose target [10, 11]. Multiple studies have demonstrated an association between glycemic variability and mortality [12–19]. Several measures of glycemic variability have been studied: SD, coefficient of variation, glycemic lability index, and mean amplitude of glycemic excursion [20]. Coefficient of variation (SD/mean × 100%) normalizes glycemic variability at different mean blood glucose values. Coefficient of variation correlates with mortality in the ICU [13, 15, 17–19].

The association of glycemic variability with mortality could be independent of critical illness, a covariate, or both. Glycemic variability may be a unique patient attribute, it may be the result of unnecessary inter-physician variation while attempting to control blood sugar with insulin, or it may be a consequence of hypoglycemia, believed to confer harm. We studied the association between coefficient of variation of glucose and mortality. While this association is well-documented in previous studies [12–19], in this study, we eliminated inter-physician variation by standardizing physician decisions with eProtocol-Insulin, an explicit, replicable, electronic protocol for managing blood glucose in ICU patients [21, 22]. Clinician compliance with eProtocol-insulin recommendations is 95%, and the implementation of eProtocol-insulin has resulted in clinical reproducibility of blood glucose metrics across multiple environments [21–23]. We also assessed whether the association between glycemic variability and mortality was independent of hypoglycemia and other patient attributes.

Methods

Data collection

Using Intermountain Healthcare’s electronic medical record, we performed a retrospective cohort analysis of all patients supported with eProtocol-insulin from November 2006 to August 2012 (Intermountain Healthcare Institutional Review Board, number 1008548, approved this study, and allowed waiver of informed consent due to its retrospective nature). Patients were drawn from 14 different ICUs from 8 different hospitals. These open ICUs included medical (2), surgical (2), and mixed (9) patient populations, teaching (2) and non-teaching (12) ICU’s. Diagnostic categories of reason for admission were not assessed, although we excluded patients with diabetic ketoacidosis, as we believe they comprised a different patient experience than the typical ICU patient on intravenous insulin for blood glucose management. Similarly, we also excluded patients supported with eProtocol-insulin for <24 hours or with <10 blood glucose measurements. We included only a patient’s first ICU admission during the study period. We stratified the data by presence or absence of diabetes mellitus (Figure 1), determined by the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 9th revision: (ICD-9) 249.x-250.x code. We calculated the acute physiology component of the acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE)-II score (excluding age and chronic comorbidities) to avoid co-linearity in our regression model. We calculated the Charlson comorbidity index using ICD-9 codes [24, 25].

Glucose management

The eProtocol-Insulin algorithm is as follows:

Blood glucose management in Intermountain Healthcare ICUs includes standardized institutional processes. All ICUs used the OneTouch SureStep (LifeScan, Milpitas, CA, USA) bedside glucose meter until 2010, when all facilities switched to the HemoCue (Quest Diagnostics, Cypress CA, USA) glucose meter. All glucose meters were calibrated nightly. All ICUs administered intravenous (IV) regular insulin using a smart pump in plastic tubing with a concentration of 1 unit/mL. The time interval of blood glucose measurements was explicitly determined by eProtocol-insulin, based on glucose stability. All study ICUs have a 2:1 patient/nurse ratio. eProtocol-insulin does not contain detailed nutrition rules but adjusts recommendations based on glucose-calories above or below half the estimated basal caloric requirement [26]. Both the decision to initiate eProtocol-insulin and the blood glucose target were determined by the individual practitioner at a target of either 95 mg/dL (corresponding to an expected range of 80 to 110 mg/dL), or at 115 mg/dL (corresponding to an expected range of 90 to 140 md/dL). Shortly after the publication of NICE-SUGAR, most physicians switched from the 95 mg/dL to the 115 mg/dL target [27]. eProtocol-insulin discontinues IV insulin and recommends concentrated IV dextrose when blood glucose is <60 mg/dL. eProtocol-insulin support is discontinued if patients are receiving bolus feeds.

Statistical analysis

Given the non-parametric distribution of the data, we compared central tendencies between groups using the Mann–Whitney U-test, and compared proportions using the Chi-squared test. We performed multivariable logistic regression to assess the impact of blood glucose coefficient of variation on 30-day mortality in the diabetic and non-diabetic populations. In the regression models, we adjusted for age, acute physiology score, Charlson comorbidity score, presence of diabetes, glucose coefficient of variation and occurrence of hypoglycemia (at least one blood glucose <60 mg/dL). We stratified the models for presence or absence of diabetes. Because we anticipated the coefficient of variation would vary co-linearly with hypoglycemia, we decided a priori to use a likelihood ratio test to determine the independent contribution of coefficient of variation on mortality in a model that included hypoglycemia. In all multivariable regression models, we assessed the role of multi-co-linearity with variance inflation factor, the existence of specification error with a link test, and the calibration of the model with Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. All displayed P-values are two-sided. We analyzed the data with Stata-12 statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

We identified 6,101 patients, of whom 46.7% had diabetes. Diabetic patients were older, had higher mean blood glucoses, higher SD of glucose, and higher coefficients of variation than non-diabetic patients (Table 1). Diabetic patients had greater comorbidity scores (6 versus 2) and lower acute physiology scores (19 versus 21) than non-diabetic patients. Diabetic patients were also more likely than non-diabetic patients to have hypoglycemia. The overall rate of hypoglycemia in all patients (glucose <60 mg/dL) and severe hypoglycemia (<40 mg/dL) were 24% and 3%. There was no difference in 30-day mortality between diabetic and non-diabetic patients (P = 0.15).

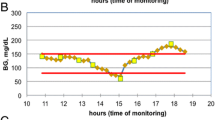

Univariable analysis of the unadjusted coefficient of variation was strongly associated with mortality for the entire cohort (odds ratio (OR) 1.25 for every 10% increase, 95% CI = 1.19, 1.32, P <0.001). Unadjusted coefficient of variation was more strongly associated with mortality in non-diabetics (OR 1.48, 95% CI = 1.37, 1.62, P <0.001) than in diabetics (OR 1.14, 95% CI = 1.06, 1.23, P <0.001, Figure 2).

After multivariable regression model adjustment for age, gender, disease severity, comorbidities, diabetic status, blood glucose target, and hypoglycemia, the coefficient of variation was still associated with mortality (OR 1.23 for every 10% increase, 95% CI = 1.16, 1.31, P <0.001, Table 2). This association was significantly greater in non-diabetic patients (OR 1.37, 95% CI = 1.25, 1.50, P <0.001) than diabetic patients (OR 1.15, 95% CI = 1.06, 1.24, P = 0.001). The effect of coefficient of variation on mortality was independent of hypoglycemia in the entire cohort (χ2 = 45.62, P <0.001), in diabetic patients (χ2 = 11.20, P = 0.001), and in non-diabetic patients (χ2 = 44.40, P <0.001). Other covariates associated with increased mortality were age, acute physiology score, Charlson comorbidity index, and occurrence of blood glucose <60 mg/dL. The presence of diabetes was associated with decreased mortality in the multivariate model (OR 0.64, P <0.001). The association between coefficient of variation and mortality was maintained in the subset of patients who never had a hypoglycemic event (OR 1.20, 95% CI = 1.12, 1.29, P <0.001).

Discussion

We demonstrate that coefficient of blood glucose variation is independently associated with 30-day mortality in the critically ill population. This association is independent of age, disease severity, comorbidities, diabetic status, and hypoglycemia. While previous work in this area has demonstrated an association of coefficient of variation and mortality, this study adds value to the literature in three ways: (1) we employed an explicit electronic protocol to significantly reduce inter-clinician variability in the method of insulin titration; (2) we demonstrated that coefficient of variation is associated with mortality even in diabetic patients, and (3) we accounted for hypoglycemia when analyzing coefficient of variation. Notably, our rates of severe hypoglycemia (<40 mg/dL) were significantly lower than reported in the lower glucose target of the NICE-SUGAR study (3.4% versus 6.8%, P <0.0001) [28].

Previous studies investigating the effects of glucose variability either lacked any specific protocol for insulin management [12, 15], or allowed variation with clinician judgment in adjustment of insulin and in frequency of blood glucose measurements [1, 4, 7]. Several previous studies have either omitted diabetic status from analysis, or did not stratify the analysis based on diabetic status [12, 14–16, 29]. Both Krinsley and Sechterberger stratified analysis on diabetic status, and demonstrated that coefficient of variation was associated with mortality in non-diabetic, but not in diabetic patients [17–19]. We believe it necessary to stratify analysis upon diabetic status. Diabetic patients behave differently than non-diabetic patients regarding intravenous insulin therapy [16–19, 30–33]. Although prior studies also demonstrated that hypoglycemia and glycemic variability contribute to mortality, many do not demonstrate that the association of glycemic variability to mortality is independent of hypoglycemia [12, 14, 16, 29, 34]. From these studies we know neither how much collinearity exists between hypoglycemia and the chosen metric of glycemic variability, nor how much of the association between glycemic variability and mortality is driven by hypoglycemia. Krinsley demonstrated that the association still holds even after excluding severe hypoglycemia, suggesting that the relationship is not driven by hypoglycemia [13]. Our data are congruent with Krinsley’s finding that the association of coefficient of variation on mortality is maintained in patients without hypoglycemia. Furthermore, our data demonstrate that the association of coefficient of variation and mortality is independent of hypoglycemia even when hypoglycemic patients are included in the model. To our knowledge, we are the first to demonstrate that the association between blood glucose coefficient of variation and mortality occurs in diabetic patients, and the association occurs when using data from a replicable clinician decision method (eProtocol-insulin).

Blood glucose variability seems to be an important characteristic of a patient’s glucose homeostasis, but also may be a characteristic of the clinician’s treatment. Less glycemic variability may reflect more precise glucose management with IV insulin, and may result from more fastidious medical care, leading to improved outcomes [10]. Confounding from clinician variation in medical care is likely in studies that lack an explicit and reproducible method for insulin titration and blood glucose management. Such confounding is unlikely in this study as a unique feature of this study is its reliance on eProtocol-insulin, an electronic protocol that uses explicit and detailed rules for intravenous insulin and blood glucose measurement to achieve 95% clinician compliance and clinical reproducibility [21–23]. Hence, there is little inter-clinician variability in glucose management in the current study population.

Glycemic variability may cause harmful effects. Among patients with type II diabetes, increased glycemic variability is associated with increased protein kinase C-β, a marker of oxidative stress [35]. Increased glycemic variability also increases oxidative stress at the cellular level [36, 37]. Nevertheless, no study, including this one, has demonstrated a causal relationship between glycemic variability and death in the ICU.

Glycemic variability may simply be an epiphenomenon of a critically ill patient’s inability to maintain homeostasis. While this study cannot determine the validity of this possibility, some of its results offer insight into the relationship between glycemic variability and mortality. Because the eProtocol-insulin was identical for diabetic and non-diabetic patients, the differences in glycemic variability between these two groups are likely caused by patient-specific factors. A non-diabetic patient who requires IV insulin has, by definition, already lost the ability to maintain glucose homeostasis. At least some component of this glucose dysregulation is reasonably inferred to be the result of critical illness, not its cause. We found the association between blood glucose coefficient of variation and mortality was significantly greater in non-diabetic than in diabetic patients. Although we adjusted for disease severity, the acute physiology score we used is far from a comprehensive assessment of disease severity. We are unable to account for every possible indicator of disease severity, and it is possible that unmeasured indicators of disease severity confound the association between glycemic variability and mortality. If the increased mortality was caused solely by increased glycemic variability, we would expect similar associations in diabetic and non-diabetic patients, and expect that diabetic patients (with greater glycemic variability), would have greater mortality. Our results support neither of these expectations. While we think it is likely that some component of glycemic variability is caused by disease severity, we recognize that increased glycemic variability itself may have an adverse effect on patient outcome. Our data do not allow for inferences of mortality benefit from reduction of glycemic variability.

Our study used a threshold of 60 mg/dL for hypoglycemia. This threshold is lower than the 70 mg/dL threshold commonly reported in the literature. Our rationale for this threshold is that the protocol becomes discontinuous at <60 mg/dL (insulin is suspended and glucose is administered), which may have significant effects on glycemic variation.

While there was no statistically significant difference in mortality rate among diabetic and non-diabetic patients, diabetes was associated with reduced mortality in the multivariable analysis. The association of diabetes with comparable or decreased mortality in the critically ill is well-documented in the literature [18, 19, 31, 38–42]. One explanation is that acute dysglycemia may confer less harm in the diabetic patient who has developed a tolerance to the complications of hyperglycemia. The GLUT4 transporter, a signaling molecule that affects myocardial function, is downregulated with chronic hyperglycemia, and is upregulated with administration of insulin [43, 44]. Another possible explanation is selection bias. The high proportion of study patients with diabetes suggests that physicians were more likely to use eProtocol-insulin in diabetic than non-diabetic patients. Non-diabetic patients had greater severity of illness than diabetic patients (by acute physiology score). We suspect the severely ill non-diabetic patients were more likely to be selected for blood glucose management with eProtocol-insulin, and therefore diabetes (in less severely ill patients) was associated with reduced mortality.

This study’s results are limited, although we studied many patients from a heterogenous population (community and referral hospitals, medical and surgical ICUs, private and academic hospitals). Generalizability of the results is limited by our use of eProtocol-insulin and by the retrospective analysis. Physicians were not required to use eProtocol-insulin, and we do not know how many patients were managed without eProtocol-insulin. We suspect selection bias because patients supported with eProtocol-insulin may be substantially different than those who were not. For example, the proportion of diabetic patients (47%) was much higher in this study than expected for a typical ICU. The ICD-9 determination of diabetes did not require hemoglobin A1c values. Undiagnosed diabetes might then be erroneously categorized as non-diabetic. We do not have the data to pursue further the selection bias issue. We excluded a large number of patients, including those with diabetic ketoacidosis or who were supported with eProtocol-insulin for <1 day. While patients on this study did not receive bolus feeding, we did not quantify enteral or parenteral glucose amount, duration, or frequency. We expect such factors are associated with glucose variability, and should be controlled in future prospective studies. Blood glucose measurements from capillary glucose meters have known analytic inaccuracies [45, 46], although the meters were calibrated daily according to industry standards.

The clinically relevant question is whether reduction of glycemic variability will improve outcomes. The answer to that question will require a prospective study aimed at reducing glycemic variability. The large prospective studies looking at glucose management in the critically ill have compared different mean blood glucose targets, with little or less attention paid to other glucose metrics, such as glycemic variability [1, 4, 6, 7]. Furthermore the relationship between glycemic variability, blood glucose target range, and the method of blood glucose control is largely ignored in previously published prospective studies. Multiple studies have reported incongruent results. We believe these disparate results follow from testing different protocols in different populations, with varying, and usually unreported, clinician compliance. Consequently, we understand little more about best practice for blood glucose management than we did before the publication by van den Berghe et al. [1]. Future studies should employ replicable protocols, and should include assessment and treatment of glycemic variability, among other glucose metrics. Constructing such a study may be difficult in human subjects without deliberately inducing undesirable variations in blood glucose.

Conclusion

In critically ill patients treated with an explicit, electronic insulin protocol (eProtocol-insulin), blood glucose coefficient of variation was associated with 30-day mortality. This association was present in diabetic as well as in non-diabetic patients. The association was independent of hypoglycemia, blood glucose target, age, disease severity, and comorbidities. Future studies should include assessment of blood glucose variability.

Key messages

-

Blood glucose coefficient of variation is associated with 30-day mortality in ICU patients receiving intravenous insulin.

-

This association also persists in diabetic patients, and is independent of hypoglycemia.

-

This association is unlikely to be the result of inter-physician variation, as we standardized physician decisions with an explicit, replicable insulin protocol.

Abbreviations

- ICD-9:

-

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 9th revision

- IV:

-

intravenous

- NICE-SUGAR:

-

Normoglycaemia in intensive care evaluation and survival using glucose algorithm regulation

- OR:

-

odds ratio.

References

van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx F, Schetz M, Vlasselaers D, Ferdinande P, Lauwers P, Bouillon R: Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2001, 345: 1359-1367. 10.1056/NEJMoa011300

Griesdale DE, de Souza RJ, van Dam RM, Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Malhotra A, Dhaliwal R, Henderson WR, Chittock DR, Finfer S, Talmor D: Intensive insulin therapy and mortality among critically ill patients: a meta-analysis including NICE-SUGAR study data. CMAJ 2009, 180: 821-827. 10.1503/cmaj.090206

Ingels C, Debaveye Y, Milants I, Buelens E, Peeraer A, Devriendt Y, Vanhoutte T, Van Damme A, Schetz M, Wouters PJ, van den Berghe G: Strict blood glucose control with insulin during intensive care after cardiac surgery: impact on 4-years survival, dependency on medical care, and quality-of-life. Eur Heart J 2006, 27: 2716-2724. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi855

Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Hermans G, Meersseman W, Wouters PJ, Milants I, Van Wijngaerden E, Bobbaers H, Bouillon R: Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl J Med 2006, 354: 449-461. 10.1056/NEJMoa052521

Preiser JC, Devos P, Ruiz-Santana S, Melot C, Annane D, Groeneveld J, Iapichino G, Leverve X, Nitenberg G, Singer P, Wernerman J, Joannidis M, Stecher A, Chioléro R: A prospective randomised multi-centre controlled trial on tight glucose control by intensive insulin therapy in adult intensive care units: the Glucontrol study. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 1738-1748. 10.1007/s00134-009-1585-2

Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, Meier-Hellmann A, Ragaller M, Weiler N, Moerer O, Gruendling M, Oppert M, Grond S, Olthoff D, Jaschinski U, John S, Rossaint R, Welte T, Schaefer M, Kern P, Kuhnt E, Kiehntopf M, Hartog C, Natanson C, Loeffler M, Reinhart K: Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 2008, 358: 125-139. 10.1056/NEJMoa070716

Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, Blair D, Foster D, Dhingra V, Bellomo R, Cook D, Dodek P, Henderson WR, Hébert PC, Heritier S, Heyland DK, McArthur C, McDonald E, Mitchell I, Myburgh JA, Norton R, Potter J, Robinson BG, Ronco JJ: Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2009, 360: 1283-1297.

Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Chou R, Snow V, Shekelle P: Use of intensive insulin therapy for the management of glycemic control in hospitalized patients: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2011, 154: 260-267. 10.7326/0003-4819-154-4-201102150-00007

Moghissi ES, Korytkowski MT, DiNardo M, Einhorn D, Hellman R, Hirsch IB, Inzucchi SE, Ismail-Beigi F, Kirkman MS, Umpierrez GE: American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Endocr Pract 2009, 15: 353-369. 10.4158/EP09102.RA

Egi M, Bellomo R, Reade MC: Is reducing variability of blood glucose the real but hidden target of intensive insulin therapy? Crit Care 2009, 13: 302. 10.1186/cc7755

Krinsley JS: Glycemic variability in critical illness and the end of Chapter 1. Crit Care Med 2010, 38: 1206-1208. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d3aba5

Ali NA, O'Brien JM Jr, Dungan K, Phillips G, Marsh CB, Lemeshow S, Connors AF Jr, Preiser JC: Glucose variability and mortality in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 2316-2321. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181810378

Krinsley JS: Glycemic variability: a strong independent predictor of mortality in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 3008-3013. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818b38d2

Hermanides J, Vriesendorp TM, Bosman RJ, Zandstra DF, Hoekstra JB, Devries JH: Glucose variability is associated with intensive care unit mortality. Crit Care Med 2010, 38: 838-842. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cc4be9

Egi M, Bellomo R, Stachowski E, French CJ, Hart G: Variability of blood glucose concentration and short-term mortality in critically ill patients. Anesthesiology 2006, 105: 244-252. 10.1097/00000542-200608000-00006

Meyfroidt G, Keenan DM, Wang X, Wouters PJ, Veldhuis JD, Van den Berghe G: Dynamic characteristics of blood glucose time series during the course of critical illness: effects of intensive insulin therapy and relative association with mortality. Crit Care Med 2010, 38: 1021-1029. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cf710e

Krinsley JS: Glycemic variability and mortality in critically ill patients: the impact of diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2009, 3: 1292-1301. 10.1177/193229680900300609

Krinsley JS, Egi M, Kiss A, Devendra AN, Schuetz P, Maurer PM, Schultz MJ, van Hooijdonk RT, Kiyoshi M, Mackenzie IM, Annane D, Stow P, Nasraway SA, Holewinski S, Holzinger U, Preiser JC, Vincent JL, Bellomo R: Diabetic status and the relation of the three domains of glycemic control to mortality in critically ill patients: an international multicenter cohort study. Crit Care 2013, 17: R37. 10.1186/cc12547

Sechterberger MK, Bosman RJ, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Siegelaar SE, Hermanides J, Hoekstra JB, De Vries JH: The effect of diabetes mellitus on the association between measures of glycaemic control and ICU mortality: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care 2013, 17: R52. 10.1186/cc12572

Rodbard D: Clinical interpretation of indices of quality of glycemic control and glycemic variability. Postgrad Med 2011, 123: 107-118. 10.3810/pgm.2011.07.2310

Morris AH, Orme J Jr, Truwit JD, Steingrub J, Grissom C, Lee KH, Li GL, Thompson BT, Brower R, Tidswell M, Bernard GR, Sorenson D, Sward K, Zheng H, Schoenfeld D, Warner H: A replicable method for blood glucose control in critically Ill patients. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 1787-1795. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181743a5a

Thompson BT, Orme JF, Zheng H, Luckett PM, Truwit JD, Willson DF, Duncan Hite R, Brower RG, Bernard GR, Curley MA, Steingrub JS, Sorenson DK, Sward K, Hirshberg E, Morris A: Multicenter validation of a computer-based clinical decision support tool for glucose control in adult and pediatric intensive care units. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2008, 2: 357-368. 10.1177/193229680800200304

Morris AH, Orme J, Rocha BH, Holmen J, Clemmer T, Nelson N, Allen J, Jephson A, Sorenson D, Sward K, Warner H: An electronic protocol for translation of research results to clinical practice: a preliminary report. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2008, 2: 802-808. 10.1177/193229680800200508

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA: Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992, 45: 613-619. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8

Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J: Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994, 47: 1245-1251. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5

Harris JA, Benedict FG: A Biometric Study of Human Basal Metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1918, 4: 370-373. 10.1073/pnas.4.12.370

Lanspa MJ, Hirshberg EL, Phillips GD, Holmen J, Stoddard G, Orme J: Moderate glucose control is associated with increased mortality compared with tight glucose control in critically ill patients without diabetes. Chest 2013, 143: 1226-1234. 10.1378/chest.12-2072

Finfer S, Liu B, Chittock DR, Norton R, Myburgh JA, McArthur C, Mitchell I, Foster D, Dhingra V, Henderson WR, Ronco JJ, Bellomo R, Cook D, McDonald E, Dodek P, Hébert PC, Heyland DK, Robinson BG, NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators: Hypoglycemia and risk of death in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2012, 367: 1108-1118.

Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, Jacka MJ, Egi M, Hart GK, George C: The impact of early hypoglycemia and blood glucose variability on outcome in critical illness. Crit Care 2009, 13: R91. 10.1186/cc7921

Krinsley JS: Glycemic control, diabetic status, and mortality in a heterogeneous population of critically ill patients before and during the era of intensive glycemic management: six and one-half years experience at a university-affiliated community hospital. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006, 18: 317-325. 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2006.12.003

Egi M, Bellomo R, Stachowski E, French CJ, Hart GK, Hegarty C, Bailey M: Blood glucose concentration and outcome of critical illness: the impact of diabetes. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 2249-2255. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318181039a

Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Milants I, Wouters PJ, Bouckaert B, Bruyninckx F, Bouillon R, Schetz M: Intensive insulin therapy in mixed medical/surgical intensive care units: benefit versus harm. Diabetes 2006, 55: 3151-3159. 10.2337/db06-0855

Rady MY, Johnson DJ, Patel BM, Larson JS, Helmers RA: Influence of individual characteristics on outcome of glycemic control in intensive care unit patients with or without diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc 2005, 80: 1558-1567. 10.4065/80.12.1558

Hirshberg E, Larsen G, Van Duker H: Alterations in glucose homeostasis in the pediatric intensive care unit: Hyperglycemia and glucose variability are associated with increased mortality and morbidity. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2008, 9: 361-366. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318172d401

Monnier L, Mas E, Ginet C, Michel F, Villon L, Cristol JP, Colette C: Activation of oxidative stress by acute glucose fluctuations compared with sustained chronic hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2006, 295: 1681-1687. 10.1001/jama.295.14.1681

Quagliaro L, Piconi L, Assaloni R, Martinelli L, Motz E, Ceriello A: Intermittent high glucose enhances apoptosis related to oxidative stress in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: the role of protein kinase C and NAD(P)H-oxidase activation. Diabetes 2003, 52: 2795-2804. 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2795

Risso A, Mercuri F, Quagliaro L, Damante G, Ceriello A: Intermittent high glucose enhances apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells in culture. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2001, 281: E924-E930.

Siegelaar SE, Hickmann M, Hoekstra JB, Holleman F, DeVries JH: The effect of diabetes on mortality in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2011, 15: R205. 10.1186/cc10440

Vincent JL, Preiser JC, Sprung CL, Moreno R, Sakr Y: Insulin-treated diabetes is not associated with increased mortality in critically ill patients. Crit Care 2010, 14: R12. 10.1186/cc8866

Graham BB, Keniston A, Gajic O, Trillo Alvarez CA, Medvedev S, Douglas IS: Diabetes mellitus does not adversely affect outcomes from a critical illness. Crit Care Med 2010, 38: 16-24. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b9eaa5

Krinsley JS, Meyfroidt G, van den Berghe G, Egi M, Bellomo R: The impact of premorbid diabetic status on the relationship between the three domains of glycemic control and mortality in critically ill patients. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2012, 15: 151-160. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32834f0009

Krinsley JS, Fisher M: The diabetes paradox: diabetes is not independently associated with mortality in critically ill patients. Hosp Pract (1995) 2012, 40: 31-35. 10.3810/hp.2012.04.967

Klip A, Tsakiridis T, Marette A, Ortiz PA: Regulation of expression of glucose transporters by glucose: a review of studies in vivo and in cell cultures. FASEB J 1994, 8: 43-53.

Huang JP, Huang SS, Deng JY, Hung LM: Impairment of insulin-stimulated Akt/GLUT4 signaling is associated with cardiac contractile dysfunction and aggravates I/R injury in STZ-diabetic rats. J Biomed Sci 2009, 16: 77. 10.1186/1423-0127-16-77

Hoedemaekers CW, Klein Gunnewiek JM, Prinsen MA, Willems JL, Van der Hoeven JG: Accuracy of bedside glucose measurement from three glucometers in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 3062-3066. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186ffe6

Inoue S, Egi M, Kotani J, Morita K: Accuracy of blood-glucose measurements using glucose meters and arterial blood gas analyzers in critically ill adult patients: systematic review. Crit Care 2013, 17: R48. 10.1186/cc12567

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported with a grant from the Intermountain Research and Medical Foundation. This investigation was partly supported with funding from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant 8UL1TR000105 (formerly UL1RR025764), and by AHCPR grant #HS06594. The sponsors had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ML contributed to study conception and design, data analysis, statistical analysis, and drafting the manuscript. EH contributed to study conception and design, and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. JD contributed to study design, statistical analysis, and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. JH contributed to data analysis, revision of manuscript for important intellectual content. JO and AM contributed to study conception and design, and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. ML takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to the published article.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Lanspa, M.J., Dickerson, J., Morris, A.H. et al. Coefficient of glucose variation is independently associated with mortality in critically ill patients receiving intravenous insulin. Crit Care 18, R86 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13851

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13851