Abstract

Acute lung injury (ALI) remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients. Despite improved understanding of the pathogenesis of ALI, supportive care with a lung protective strategy of mechanical ventilation remains the only treatment with a proven survival advantage. Most clinical trials in ALI have targeted mechanically ventilated patients. Past trials of pharmacologic agents may have failed to demonstrate efficacy in part due to the resultant delay in initiation of therapy until several days after the onset of lung injury. Improved early identification of at-risk patients provides new opportunities for risk factor modification to prevent the development of ALI and novel patient groups to target for early treatment of ALI before progression to the need for mechanical ventilation. This review will discuss current strategies that target prevention of ALI and some of the most promising pharmacologic agents for early treatment of ALI prior to the onset of respiratory failure that requires mechanical ventilation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1994, the American and European Consensus Conference (AECC) established specific clinical criteria for acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), providing standardization for clinical research and multicenter clinical trials [1]. However, despite improved understanding of the etiologies and pathophysiology of ALI in the nearly 20 years since formation of the AECC criteria [2], ALI remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Rubenfeld and colleagues [3] recently estimated the incidence of ALI at nearly 200,000 cases per year in the United States with an in-hospital mortality rate of nearly 40%. Lung protective strategies of mechanical ventilation remain the only therapies with an established survival advantage [4–7]. However, despite advances in the supportive care of patients with ALI, no disease specific treatments targeting the pathogenesis of the underlying lung injury can currently be recommended.

Numerous pharmacologic therapies have failed to demonstrate benefit in multicenter clinical trials [8, 9]. However, clinical trials have largely targeted enrolling patients within 48 hours of meeting AECC criteria while receiving mechanical ventilation, potentially delaying initiation of treatment until several days after onset of lung injury. Based on the successful paradigm of early goal-directed therapy for sepsis [10], greater clinical benefit may derive from intervening earlier in the course of ALI, prior to meeting current AECC criteria or prior to the onset of respiratory failure and need for mechanical ventilation.

Definitions: prevention versus early treatment

The AECC criteria for ALI and ARDS include acute respiratory failure and require calculation of the partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2)/fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio [1]. How one interprets the term 'respiratory failure' and the mode of oxygen delivery used to estimate the FiO2 may blur the distinction between prevention and early treatment of ALI. Traditionally, the diagnosis has been limited to patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Rubenfeld and colleagues [3], in the most rigorous epidemiologic study to date, interpreted respiratory failure to include mechanical ventilation via a noninvasive facemask or endotracheal tube. However, other authors have expanded interpretation of the consensus criteria to include non-mechanically ventilated patients and patients outside of the ICU [11–14]. Ferguson and colleagues [11] prospectively followed 815 patients admitted to a hospital ward or an ICU with at least one pre-defined risk factor for ALI. Fifty-three patients (7%) developed ALI. Of these, 17 were diagnosed with ALI outside of the ICU (15 of which were never admitted to an ICU) and 24 were not receiving mechanical ventilation at the time of the diagnosis.

While expanding the definition of ALI to non-mechanically ventilated patients may contribute to earlier recognition, it risks jeopardizing standardization of study populations. Quantifying lung injury by a PaO2/FiO2 ratio in spontaneously breathing patients ignores the beneficial effects of positive pressure ventilation on lung recruitment and oxygenation and is likely not directly comparable to mechanically ventilated patients to whom this criterion has traditionally been applied. Also, expanding the criteria to patients who do not require positive pressure ventilation focuses the definition of respiratory failure on the need for supplemental oxygen (a PaO2 <63 mmHg on room air qualifies as a PaO2/FiO2 ratio <300) without regard for respiratory distress or impending respiratory arrest.

Therefore, our research group empirically derived clinical criteria for early ALI in a prospective series of 100 patients identified at the time of admission [15]. Defined by bilateral opacities on the chest radiograph and an oxygen requirement >2 L/minute to maintain peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) >90% in the absence of isolated left atrial hypertension, early ALI identified patients who subsequently progressed to ALI requiring mechanical ventilation with 73% sensitivity and 79% specificity. Subsequently, Gajic and colleagues [16] prospectively derived the Lung Injury Prediction Score (LIPS; Table 1) in a multicenter cohort of 5,000-plus patients admitted with at least one known risk factor for ALI. A LIPS >4 provided the best discrimination with an associated sensitivity of 69%, specificity of 78% and a positive predictive value of 18%.

For some pulmonary-specific risk factors included in the LIPS (that is, pneumonia, aspiration, SpO2 <95% or FiO2 >35%), the distinction between prevention and early identification may be semantic while for others (non-pulmonary sepsis, high risk elective surgery, comorbidities) the distinction is real - affecting not only the prevalence but also the time of progression to ALI. In our cohort, the prevalence of ALI was 33% and median time to progression was less than 24 hours [15]. Similarly, rapid rates of progression were reported by Ferguson and colleagues (median 1 day, interquartile range 0 to 4) [11] and Pepe and colleagues (76% within 24 hours) [17]. In the LIPS cohort, which included admissions for high risk surgeries, prevalence of ALI was 7% and progression to ALI occurred over a median of 2 days (interquartile range 1 to 4 days) [16]. These differences may have important implications when selecting strategies to identify patients within an adequate window to initiate appropriate therapeutic or preventative therapies. The LIPS criteria provide a longer time window for patient identification but preventative strategies will need to include more patients, many of whom will not develop ALI regardless of intervention. The criteria in our study identified a group of patients with a higher likelihood of developing ALI, although the time interval for intervention was shorter. Also, identifying early but existing lung injury on chest radiograph is inherently subjective and requiring recognition of radiographic abnormalities may preclude early identification of some patients, particularly high risk surgical patients.

Improved recognition of high risk patients

More sensitive and earlier recognition of patients with or at high risk for developing ALI will be integral to any strategy targeting early intervention. Herasevich and colleagues [18] at the Mayo clinic in Rochester performed an automated continuous surveillance of 3,795 ICU patients using their 'ALI sniffer' (PaO2/FiO2 <300; boolean query of radiographic reports for 'bilateral' and 'infiltrate' or 'edema') and identified 325 patients with ALI with a sensitivity and a specificity of 95% and 89%, respectively. Physician recognition of ALI was present at the time of 'sniffer' identification in only 27% of patients and there was an associated use of larger tidal volumes (9.2 versus 8.0 ml/kg predicted body weight) in unrecognized cases of ALI [18]. The same authors subsequently demonstrated that automated surveillance and text page notification of physicians and respiratory therapists reduced time of exposure (41 ± 76 versus 27 ± 77 hours, P = 0.004) to potentially injurious mechanical ventilation (defined as a tidal volume >8 cc/kg) in patients with ALI [19].

Prevention strategies

There is growing recognition that at least a subset of ALI occurs as a 'two-hit' phenomenon. A predisposing condition, such as an inflammatory endothelial (that is, sepsis) or epithelial (that is, aspiration) injury, is followed by a second insult (that is, mechanical ventilation or transfusion of blood products), resulting in activation of primed neutrophils and progression to ALI. Similar to commonly employed practices for stress ulcer and deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis, strategies targeting risk factor modification (that is, avoiding a 'second-hit') in at-risk patients have the potential to substantially reduce rates of ALI.

Early appropriate management of sepsis

In a multivariate analysis of risk factors for ALI, Iscimen and colleagues [20] found that delayed early goal-directed resuscitation and delayed administration of appropriate antibiotics were both independent predictors of progression to ALI. In an ancillary study of the LIPS cohort, a net fluid balance of greater than 2 liters was an independent predictor of developing ALI [21]. While an observational design does not allow ideal accounting for confounding by indication in patients with a positive fluid balance, these studies suggest that early but judicious fluid resuscitation for patients with severe sepsis, followed by a conservative fluid strategy after resolution of shock, might reduce the number of patients who progress to ALI.

Restrictive transfusion protocols

There is growing evidence that transfusion of blood products plays an important role in the pathogenesis of ALI in at-risk patients. Transfusion related ALI (TRALI) is the best characterized of the 'two hit' models for ALI [22]. First, the pulmonary vascular endothelium is activated by one or more endogenous stimuli (that is, sepsis, surgery), resulting in vascular adherence of activated neutrophils [23, 24]. A second event, the transfusion of antibodies to leukocyte antigens or the infusion of bioactive lipids, results in neutrophil-mediated injury to the vascular endothelium with increased permeability edema and ALI [22, 25]. Quantification of the risk of transfusion is challenged by the current criteria for TRALI, which exclude patients with known risk factors for ALI [26, 27]. Reported rates of TRALI, based on recognition of overt cases in patients without known risk factors for ALI (that is, 'first-hits'), are low [28, 29]. However, Gajic and colleagues [30] observed an incidence of TRALI of 8% in 901 consecutively transfused medical ICU patients and 12% of patients had worsening of their oxygenation following transfusion. Expanding the definition to include delayed TRALI (development of ALI 6 to 72 hours after transfusion regardless of existing risk factors) increases the incidence to 25% with an associated mortality of 40% [31]. Also, plasma-rich products (that is, fresh frozen plasma and platelets), particularly from multiparous female donors, carry a greater risk of TRALI than packed red cells [30, 32]. Removal of female donors from the plasma donor pool beginning in 2006 has been associated with reduced rates of TRALI [33]. Widespread adoption of restrictive transfusion protocols in high risk patients may provide further reductions in rates of ALI.

Lung protective ventilation

Lung protective ventilation remains the only specific therapy for ALI with a proven survival advantage [4]. However, additional benefit may be derived from implementing lung protective ventilation strategies in patients without ALI. Gajic and colleagues [34] found a nearly 30% increased risk of ALI for every 1 cc/kg increase in the day 1 tidal volume above 6 cc/kg in mechanically ventilated patients without ALI (odds ratio 1.29, 95% confidence interval 1.12 to 1.51; Figure 1). A subsequent clinical trial of 6 versus 10 ml/kg tidal volumes in mechanically ventilated patients without ALI was stopped early due to higher rates of ALI in the higher tidal volume group [35] (Figure 2).

Proportion of patients who developed acute lung injury (ALI) according to tidal volume in patients mechanically ventilated for >48 hours without ALI at time of intubation. Tidal volume (Vt) ≤ 9 ml/kg predicted body weight (PBW; n = 66); Vt 9 to 12 ml/kg PBW (n = 160); Vt ≥ 12 ml/kg PBW (n = 100). *Adjusted P-value from a multiple logistic regression model including tidal volume, transfusion, postoperative, height, female gender, restrictive lung disease, and acidosis (pH <7.35); tidal volume was treated as a continuous variable. Reprinted from [34] with permission from Critical Care Medicine.

Kaplan-Meier curve of incidence of acute lung injury (left), percentage of patients weaned from ventilator (middle), and mortality (right) in patients mechanically ventilated with conventional tidal volume (solid circles) or lower tidal volumes (open circles). ALI, acute lung injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome. Reprinted from [35] with permission from Critical Care.

Non-invasive ventilation

The role of non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) in ALI remains uncertain. There are no large multicenter clinical trials of NIV specifically for ALI. A small trial of immunocompromised patients with pulmonary infiltrates and acute respiratory failure found NIV reduced rates of intubation and mortality [36]. In a trial of 102 patients with severe hypoxemic respiratory failure (34 with pneumonia and 15 meeting criteria for ARDS), Ferrer and colleagues [37] found NIV reduced rates of intubation and 90-day mortality. However, in a trial of 123 patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (102 of whom had ALI), NIV did not reduce rates of intubation or mortality despite early physiologic improvements [38]. Also, more adverse events occurred in the NIV group. In a multicenter review, 79 of 147 patients with ARDS avoided intubation with NIV. However, these 147 patients were a subset of a total of 479 patients with ARDS. Most were intubated without receiving NIV so these 147 patients likely represent a highly selected population. In this cohort, a Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II >34 and inability to improve the PaO2/FiO2 ratio after 1 hour predicted failure of NIV [39]. In another study, 38 (70%) of 54 patients with ALI (including all 19 patients with shock) initially managed with NIV eventually required intubation [40]. Patients who failed NIV also had higher than predicted mortality (68% versus 39%, P < 0.01).

NIV has not been adequately evaluated in prospective clinical trials to recommend its routine use in patients with ALI. If used, however, a general guideline is that it should be reserved for patients without shock and with less severe lung injury. Patients should be reassessed within one hour and patients without significant physiologic improvement should probably be intubated to avoid potential negative consequences of delayed intubation.

Improved supportive care

Given the growing understanding of the importance of secondary risk factors in the pathogenesis of ALI, improved standardization of the supportive care of high risk patients has the potential to substantially reduce the incidence of ALI. In Olmstead County, Minnesota (home to the Mayo Clinic, which has been a major force in the field of lung injury prevention), Li and colleagues [41] found an 8 year decline in the incidence of ARDS among ICU patients from 82 to 39 per 100,000 person years despite a higher initial severity of illness (Figure 3). The reduction in ARDS was due entirely to a reduction in hospital acquired-ARDS with no difference in the prevalence of ARDS on admission to the ICU. Similarly, in a trauma-specific cohort, Ciesla and colleagues [42] found a reduction in rates of ALI (from 43% to 25%) and multiple organ failure (33% to 12%) despite similar injury severity in 897 patients enrolled over a 6.5 year study period.

Trends in age- and sex-specific incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome from 2001 to 2008 in Olmsted County, Minnesota (incidence obtained by validated screening of ICU admission within Mayo Clinic). Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals. ALI, acute lung injury. Reprinted from [41] with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2012 American Thoracic Society. Official Journal of the American Thoracic Society.

The United States Critical Illness and Injury Trials group and the Lung Injury Prevention Study (USCIITG-LIPS) investigators have developed the Checklist for Lung Injury Prevention (CLIP) in an attempt to standardize the care of at-risk patients and are currently validating its utility. The checklist targets increased compliance with evidence-based practice in at risk patients (that is, aspiration precautions, early appropriate antibiotics and goal-directed therapy for sepsis, restrictive transfusion protocols, lung protective ventilation for intubated patients and restrictive fluid management after reversal of shock). The utility of this web-based clinical decision tool, for either impacting management or improving patient outcomes, needs validation. However, widespread adoption of standard supportive care practices has the potential to further reduce the incidence of ALI.

Pharmacologic strategies for prevention or early treatment

Currently, no pharmacologic therapy can be recommended as standard management of ALI [8, 9]. However, intervention with pharmacologic agents may be more successful if initiated prior to the onset of lung injury or at least prior to progression to respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. Multiple novel therapies have emerged as promising candidates for trials of prevention or early treatment of ALI.

Aspirin

Aspirin is inexpensive, safe and a readily available therapy with potential to prevent ALI. Looney and colleagues [43] described the importance of platelet and neutrophil interaction as an essential component of the 'two-hit' model of TRALI. In a mouse model of TRALI, pre-treatment with aspirin prevented lung injury [23]. In a multivariate analysis of the single center LIPS derivation cohort, patients receiving anti-platelet therapy at the time of admission had significantly lower rates of developing ALI [44] (Table 2). In the subsequent multicenter LIPS cohort, prehospital anti-platelet therapy remained associated with lower rates of ALI but did not quite reach statistical significance (P = 0.07) [45]. Based on these findings, the USCIITG-LIPS study group recently initiated a multicenter phase II/III trial of aspirin versus placebo in at-risk patients with a LIPS >4, targeting a reduction in rate of progression to ALI.

Statins

Statins are another reasonably safe and readily available therapy with potential for prevention or treatment of early lung injury. In murine models of sepsis, statins reduce leukocyte adherence [46, 47], attenuate release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [48–50], and improve survival [46, 48, 51]. Additionally, statins attenuate lung injury [48, 49] and pulmonary vascular permeability [48] in murine models of ALI. In humans, data from the cardiology literature show consistent reduction in plasma levels of C-reactive protein with statin therapy [52–55]. Multiple observational studies have shown improved outcomes in patients on statins at time of hospitalization for sepsis [56–60] or pneumonia [61, 62]. A recent study of 575 critically ill patients found that prehospital statin use was associated with lower rates of ALI and this effect seemed to be potentiated by prehospital aspirin use [63].

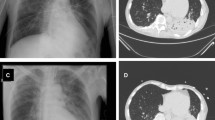

A recent phase II clinical trial in 60 mechanically ventilated patients with ALI found improvement in non-pulmonary organ dysfunction and a trend toward improved oxygenation and pulmonary mechanics in patients treated with simvastatin compared to placebo [64] (Figure 4). Two large clinical trials of statins are currently underway. The first, Simvastatin Effect on the Incidence of Acute Lung Injury/Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome (NCT01195428), targets prevention of ALI in a randomized trial of simvastatin versus placebo in 360 critically ill patients with sepsis. The second, the ARDS Network Statins for Acutely Injured Lungs from Sepsis (SAILS; NCT00979121), targets improved mortality in 1,000 mechanically ventilated ALI patients with evidence of infection randomized to rosuvastatin versus placebo within 48 hours of meeting ALI criteria.

Effects of simvastatin on pulmonary and nonpulmonary organ function. Patients with acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome were treated with 80 mg simvastatin (gray bars) or placebo (white bars). (a) Simvastatin reduces oxygenation index (OI) at day 14 but does not reach statistical significance. Data are mean and standard deviation. (b) Simvastatin reduces plateau pressure at day 14 but does not reach statistical significance. Data are mean and standard deviation. (c) Simvastatin reduces lung injury score (LIS) at day 14 but does not reach statistical significance. Data are mean and standard deviation. (d) Simvastatin reduces Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score at day 14. Data are median (interquartile range). *P < 0.05 versus placebo. Reprinted from [64] with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2012 American Thoracic Society. Official Journal of the American Thoracic Society.

Beta-2 adrenergic agonists

Animal data have shown that alveolar fluid clearance depends on active sodium and fluid transport across the alveolar epithelium [65] and that beta agonists upregulate the rate of alveolar fluid clearance in normal epithelium and models of ALI [66, 67]. Beta agonists also have anti-inflammatory properties [68] and reduce vascular permeability in models of ALI [66]. In addition, aerosolized albuterol attained therapeutic levels in pulmonary edema fluid in mechanically ventilated patients with acute respiratory failure [69].

Human observational studies have found that aerosolized beta agonists are independently associated with shorter duration of mechanical ventilation and improved survival in adult and pediatric patients with ALI [12, 70]. A European phase II trial of 40 mechanically ventilated patients with ALI randomized to intravenous salbutamol versus placebo found reduced extravascular lung water and improved lung compliance in the treatment group [71]. However, a recent multicenter trial by the ARDS Network of aerosolized albuterol in mechanically ventilated patients was stopped early for futility with a trend toward worse clinical outcomes [72]. Serum analysis of treated patients confirmed delivery of therapeutic levels of albuterol, suggesting the route of delivery does not explain the negative findings. Similarly, a follow up European multicenter randomized phase III trial of intravenous salbutamol showed no reduction in 60 day or ICU mortality in the patients treated with intravenous salbutamol [73].

However, beta agonists, particularly aerosolized beta agonists, may be more effective when initiated prior to the onset of respiratory failure. An intact functional epithelium is necessary for upregulation of alveolar fluid clearance and this may be less prevalent in more advanced stages of ALI [74]. Also, modest changes in extravascular lung water may be less relevant in mechanically ventilated patients, particularly in the context of data from the ARDS network trial that reported that fluid management practices can reduce net fluid balance by 7 liters over the course of ALI [75]. Ultimately, empiric use of aerosolized beta agonists for dyspneic patients with possible early lung injury remains common in clinical practice. Data from two large clinical trials of mechanically ventilated patients suggest this practice is not effective. A well designed clinical trial targeting prevention or treatment of early lung injury prior to the need for mechanical ventilation is needed to determine if continuation of this routine practice is warranted.

Inhaled corticosteroids

The role of corticosteroids in ALI remains controversial. In a trial of 24 patients with nonresolving ARDS, Meduri and colleagues [76] reported improved survival in patients treated with methylprednisolone, although this trial had a 2:1 randomization with several cross-overs in the placebo group. The ARDS Network subsequently attempted to confirm these findings in a large multicenter clinical trial [77]. The results demonstrated a small improvement in oxygenation, and more ventilator-free days at 60, but not at 180, days and no decrease in 60 or 180 day mortality. Also, myopathy was more common in the treatment group and there was a trend toward worse outcomes when corticosteroids were initiated after 14 days.

Inhaled corticosteroids may provide better delivery of drug to the lung while potentially avoiding negative systemic effects of corticosteroids. Pretreatment with inhaled beclomethasone reduced neutrophils and improved lung function in septic models of lung injury in pigs [78–80]. Pigs treated with inhaled terbutaline and budesonide 30 and 60 minutes post-lung injury with chlorine gas had improved oxygenation and lung compliance and combined therapy was more effective than either therapy alone [81]. Pretreatment with inhaled budesonide also reduced bronchoalveolar lavage fluid levels of neutrophils and of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6 and interleukin-1β compared to placebo and n-acetylcysteine in a lipopolysaccharide model of lung injury in rats [82].

In the LIPS cohort, patients being treated with inhaled corticosteroids at hospital admission had a reduced incidence of ALI [83]. This association was independent of multivariate adjustment using propensity score analysis (adjusted odds ratio 0.39, 95% confidence interval 0.14 to 0.93). However, 70% of patients on inhaled corticosteroids were also using inhaled beta agonists, precluding insight into the independent versus the combined effects of these two therapies in prevention of ALI. A multicenter pilot trial of inhaled corticosteroids and beta agonists in a 2 × 2 factorial design is currently being considered by the USCIITG-LIPS study group.

Potential future therapies

Preliminary animal and human data have identified other pharmacologic agents with potential benefit as early treatments of ALI. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have anti-inflammatory properties and have been shown to improve lung function in murine models of lung injury [84, 85]; however, use of these at time of hospital admission was not associated with a reduced incidence of ALI in the LIPS cohort [86].

Vitamin D is thought to play an important role in innate host immunity and lung homeostasis [87]. Vitamin D deficiency is common in critically ill patients, particularly in elderly patients and patients with sepsis [88, 89]. Vitamin D supplementation is safe and inexpensive and treatment of vitamin D deficiency may be a promising new treatment for patients with ALI and critically ill patients in general. However, in preliminary data from a case-control study of ICU patients, vitamin D deficiency was not an independent risk factor for developing ALI [90].

Altered coagulation and microvascular thrombi appear to play an important role in the pathogenesis of sepsis and ALI. In the multicenter cohort of the ARDS Network trial of lower tidal volumes, lower protein C levels and higher plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) levels were independent predictors of mortality [91]. However, a subsequent phase II clinical trial of activated protein C in patients with ALI without sepsis failed to show improvement in the duration of mechanical ventilation or mortality despite a reduction in pulmonary dead space [92]. In addition, the recently released report that activated protein C did not reduce mortality in the large randomized PROWESS II septic shock trial will markedly reduce enthusiasm for anticoagulant therapies in ALI. Although the details of this trial are not yet available, if the results show that activated protein C did not reduce the incidence of ALI in septic patients, then the potential value of anticoagulant therapies as a preventative treatment will also be diminished.

Conclusions

Prior clinical trials of several pharmacologic agents in ALI may have failed to improve outcomes in part because the trials enrolled patients who already required mechanical ventilation, thus delaying initiation of therapy until several days after the onset of lung injury. An emerging understanding of the 'two-hit' model in the pathogenesis of ALI and the importance of risk factor modification in high risk patients may provide a significant opportunity to reduce the incidence of ALI or the progression from early ALI to ventilator-dependent ALI. Sufficient evidence currently exists to recommend improved adherence to early goal-directed therapy in severe sepsis with conservative fluid management strategies after the resolution of shock; lower tidal volumes in mechanically ventilated patients; conservative protocols for transfusion of blood products (particularly plasma-rich products such as platelets and fresh frozen plasma), and aspiration precautions. The Checklist for Lung Injury Protection [93] is an online tool available to clinicians to help improve standardization of supportive care in patients at risk for developing ALI.

Any proposed therapies targeting prevention or early treatment of lung injury prior to respiratory failure should consider the additional costs and risks incurred by treating larger populations of at-risk patients, of whom only a fraction will actually develop ALI. Ideal candidates for novel pharmacologic treatments of early ALI should be inexpensive, safe and readily available. While routine use of the LIPS will help identify patients at increased risk for developing ALI, these target patients are still a relatively low risk patient population compared to standard ALI cohorts and use of expensive or high risk treatments might not be justified. Of the current candidate treatments, statins and aspirin are the best characterized and are currently being evaluated in large multicenter clinical trials. Aerosolized delivery of other treatments, including corticosteroids, beta agonists and newer therapeutics yet to be developed, may provide better delivery of drug directly to the lung while avoiding possible unwanted systemic effects.

Progress in specific treatments for ALI beyond lung protective strategies of mechanical ventilation and conservative fluid management has not yet been realized. The recent focus on prevention of ALI and early treatment of ALI patients prior to the onset of respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation has identified new populations of at-risk patients and provided new opportunities for clinical research testing therapeutic interventions in these patients.

Abbreviations

- AECC:

-

American-European Consensus Conference

- ALI:

-

acute lung injury

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- FiO2:

-

fraction of inspired oxygen

- LIPS:

-

lung injury prediction score

- NIV:

-

non-invasive mechanical ventilation

- PaO2:

-

partial pressure of oxygen

- SpO2:

-

peripheral oxygen saturation

- TRALI:

-

transfusion related acute lung injury

- USCIITG-LIPS:

-

The United States Critical Illness and Injury Trials group and the Lung Injury Prevention Study.

References

Bernard G R, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, LeGall JR, Morris A, Spragg R: Report of the American-European Consensus conference on acute respiratory distress syndrome: definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Consensus Committee. J Crit Care 1994, 9: 72-81. 10.1016/0883-9441(94)90033-7

Matthay MA, Zimmerman GA: Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: four decades of inquiry into pathogenesis and rational management. Am J Resp Cell Mol Biol 2005, 33: 319-327. 10.1165/rcmb.F305

Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, Stern EJ, Hudson LD: Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2005, 353: 1685-1693. 10.1056/NEJMoa050333

Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network N Engl J Med 2000, 342: 1301-1308.

Brower RG , Lanken PN, MacIntyre N, Matthay MA, Morris A, Ancukiewicz M, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT: Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2004, 351: 327-336.

Meade MO, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Slutsky AS, Arabi YM, Cooper DJ, Davies AR, Hand LE, Zhou Q, Thabane L, Austin P, Lapinsky S, Baxter A, Russell J, Skrobik Y, Ronco JJ, Stewart TE, Lung Open Ventilation Study Investigators: Ventilation strategy using low tidal volumes, recruitment maneuvers, and high positive end-expiratory pressure for acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008, 299: 637-645. 10.1001/jama.299.6.637

Taccone P, Pesenti A, Latini R, Polli F, Vagginelli F, Mietto C, Caspani L, Raimondi F, Bordone G, Iapichino G, Mancebo J, Guérin C, Ayzac L, Blanch L, Fumagalli R, Tognoni G, Gattinoni L, Prone-Supine II Study Group: Prone positioning in patients with moderate and severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009, 302: 1977-1984. 10.1001/jama.2009.1614

Calfee CS, Matthay MA: Nonventilatory treatments for acute lung injury and ARDS. Chest 2007, 131: 913-920. 10.1378/chest.06-1743

Levitt JE, Matthay MA: Treatment of acute lung injury: historical perspective and potential future therapies. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2006, 27: 426-437. 10.1055/s-2006-948296

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M: Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2001, 345: 1368-1377. 10.1056/NEJMoa010307

Ferguson ND, Frutos-Vivar F, Esteban A, Gordo F, Honrubia T, Penuelas O, Algora A, Garcia G, Bustos A, Rodriguez I: Clinical risk conditions for acute lung injury in the intensive care unit and hospital ward: a prospective observational study. Crit Care 2007, 11: R96. 10.1186/cc6113

Flori HR, Glidden DV, Rutherford GW, Matthay MA: Pediatric acute lung injury: prospective evaluation of risk factors associated with mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005, 171: 995-1001. 10.1164/rccm.200404-544OC

Freishtat RJ, Mojgani B, Mathison DJ, Chamberlain JM: Toward early identification of acute lung injury in the emergency department. J Investig Med 2007, 55: 423-429. 10.2310/6650.2007.00026

Quartin AA, Campos MA, Maldonado DA, Ashkin D, Cely CM, Schein RM: Acute lung injury outside of the ICU: incidence in respiratory isolation on a general ward. Chest 2009, 135: 261-268. 10.1378/chest.08-0280

Levitt JE, Bedi H, Calfee CS, Gould MK, Matthay MA: Identification of early acute lung injury at initial evaluation in an acute care setting prior to the onset of respiratory failure. Chest 2009, 135: 936-943. 10.1378/chest.08-2346

Gajic O, Dabbagh O, Park PK, Adesanya A, Chang SY, Hou P, Anderson H, Hoth JJ, Mikkelsen ME, Gentile NT, Gong MN, Talmor D, Bajwa E, Watkins TR, Festic E, Yilmaz M, Iscimen R, Kaufman DA, Esper AM, Sadikot R, Douglas I, Sevransky J, Malinchoc M, US Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group, Lung Injury Prevention Study Investigators (USCIITG-LIPS): Early identification of patients at risk of acute lung injury: evaluation of lung injury prediction score in a multicenter cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: 462-470. 10.1164/rccm.201004-0549OC

Pepe PE, Potkin RT, Reus DH, Hudson LD, Carrico CJ: Clinical predictors of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Surg 1982, 144: 124-130. 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90612-2

Herasevic h V, Yilmaz M, Khan H, Hubmayr RD, Gajic O: Validation of an electronic surveillance system for acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 1018-1023. 10.1007/s00134-009-1460-1

Herasevic h V, Tsapenko M, Kojicic M, Ahmed A, Kashyap R, Venkata C, Shahjehan K, Thakur SJ, Pickering BW, Zhang J, Hubmayr RD, Gajic O: Limiting ventilator-induced lung injury through individual electronic medical record surveillance. Crit Care Med 2011, 39: 34-39. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fa4184

Iscimen R, Cartin-Ceba R, Yilmaz M, Khan H, Hubmayr RD, Afessa B, Gajic O: Risk factors for the development of acute lung injury in patients with septic shock: an observational cohort study. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 1518-1522. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31816fc2c0

Park PK, Birkmeyer NO, Gentile N, Chang SY, Dabbagh O, Gajic O: Early cumulative fluid balance and development of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: A5592.

Silliman CC: The two-event model of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2006,34(5 Suppl):S124-131.

Looney MR , Nguyen JX, Hu Y, Van Ziffle JA, Lowell CA, Matthay MA: Platelet depletion and aspirin treatment protect mice in a two-event model of transfusion-related acute lung injury. J Clin Invest 2009, 119: 3450-3461.

Looney MR , Su X, Van Ziffle JA, Lowell CA, Matthay MA: Neutrophils and their Fc gamma receptors are essential in a mouse model of transfusion-related acute lung injury. J Clin Invest 2006, 116: 1615-1623. 10.1172/JCI27238

Bux J, Sachs UJ: The pathogenesis of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI). Br J Haematol 2007, 136: 788-799. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06492.x

Kleinman S, Caulfield T, Chan P, Davenport R, McFarland J, McPhedran S, Meade M, Morrison D, Pinsent T, Robillard P, Slinger P: Toward an understanding of transfusion-related acute lung injury: statement of a consensus panel. Transfusion 2004, 44: 1774-1789. 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.04347.x

Toy P, Popovsky MA, Abraham E, Ambruso DR, Holness LG, Kopko PM, McFarland JG, Nathens AB, Silliman CC, Stroncek D: Transfusion-related acute lung injury: definition and review. Crit Care Med 2005, 33: 721-726. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000159849.94750.51

Popovsky MA, Abel MD, Moore SB: Transfusion-related acute lung injury associated with passive transfer of antileukocyte antibodies. Am Rev Respir Dis 1983, 128: 185-189.

Popovsky MA, Moore SB: Diagnostic and pathogenetic considerations in transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfusion 1985, 25: 573-577. 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1985.25686071434.x

Gajic O, Rana R, Winters JL, Yilmaz M, Mendez JL, Rickman OB, O'Byrne MM, Evenson LK, Malinchoc M, DeGoey SR, Afessa B, Hubmayr RD, Moore SB: Transfusion-related acute lung injury in the critically ill: prospective nested case-control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007, 176: 886-891. 10.1164/rccm.200702-271OC

Marik PE, Corwin HL: Acute lung injury following blood transfusion: expanding the definition. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 3080-3084. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818c3801

Chapman C E, Stainsby D, Jones H, Love E, Massey E, Win N, Navarrete C, Lucas G, Soni N, Morgan C, Choo L, Cohen H, Williamson LM, Serious Hazards of Transfusion Steering Group: Ten years of hemovigilance reports of transfusion-related acute lung injury in the United Kingdom and the impact of preferential use of male donor plasma. Transfusion 2009, 49: 440-452. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01948.x

Eder AF, Herron RM Jr, Strupp A, Dy B, White J, Notari EP, Dodd RY, Benjamin RJ: Effective reduction of transfusion-related acute lung injury risk with male-predominant plasma strategy in the American Red Cross (2006-2008). Transfusion 2010, 50: 1732-1742. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02652.x

Gajic O, Dara SI, Mendez JL, Adesanya AO, Festic E, Caples SM, Rana R, St Sauver JL, Lymp JF, Afessa B, Hubmayr RD: Ventilator-associated lung injury in patients without acute lung injury at the onset of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 1817-1824. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000133019.52531.30

Determann RM, Royakkers A, Wolthuis EK, Vlaar AP, Choi G, Paulus F, Hofstra JJ, de Graaff MJ, Korevaar JC, Schultz MJ: Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with conventional tidal volumes for patients without acute lung injury: a preventive randomized controlled trial. Crit Care 2010, 14: R1. 10.1186/cc8230

Hilbert G , Gruson D, Vargas F, Valentino R, Gbikpi-Benissan G, Dupon M, Reiffers J, Cardinaud JP: Noninvasive ventilation in immunosuppressed patients with pulmonary infiltrates, fever, and acute respiratory failure. N Engl J Med 2001, 344: 481-487. 10.1056/NEJM200102153440703

Ferrer M, Esquinas A, Leon M, Gonzalez G, Alarcon A, Torres A: Noninvasive ventilation in severe hypoxemic respiratory failure: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003, 168: 1438-1444. 10.1164/rccm.200301-072OC

Delclaux C, L'Her E, Alberti C, Mancebo J, Abroug F, Conti G, Guérin C, Schortgen F, Lefort Y, Antonelli M, Lepage E, Lemaire F, Brochard L: Treatment of acute hypoxemic nonhypercapnic respiratory insufficiency with continuous positive airway pressure delivered by a face mask: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000, 284: 2352-2360. 10.1001/jama.284.18.2352

Antonelli M, Conti G, Esquinas A, Montini L, Maggiore SM, Bello G, Rocco M, Maviglia R, Pennisi MA, Gonzalez-Diaz G, Meduri GU: A multiple-center survey on the use in clinical practice of noninvasive ventilation as a firstline intervention for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 18-25. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000251821.44259.F3

Rana S, Je nad H, Gay PC, Buck CF, Hubmayr RD, Gajic O: Failure of noninvasive ventilation in patients with acute lung injury: observational cohort study. Crit Care 2006, 10: R79. 10.1186/cc4923

Li G, Mali nchoc M, Cartin-Ceba R, Venkata CV, Kor DJ, Peters SG, Hubmayr RD, Gajic O: Eight-year trend of acute respiratory distress syndrome: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: 59-66. 10.1164/rccm.201003-0436OC

Ciesla DJ, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Cothren CC, Banerjee A, Burch JM, Sauaia A: Decreased progression of postinjury lung dysfunction to the acute respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ failure. Surgery 2006, 140: 640-647. discussion 647-648 10.1016/j.surg.2006.06.015

Looney MR, Gropper MA, Matthay MA: Transfusion-related acute lung injury: a review. Chest 2004, 126: 249-258. 10.1378/chest.126.1.249

Erlich JM, Talmor DS, Cartin-Ceba R, Gajic O, Kor DJ: Prehospitalization antiplatelet therapy is associated with a reduced incidence of acute lung injury: a population-based cohort study. Chest 2011, 139: 289-295. 10.1378/chest.10-0891

Kor DJ, Erlich J, Gong MN, Malinchoc M, Carter RE, Gajic O, Talmor D: Pre-hospital aspirin therapy and development of acute lung injury: a secondary analysis of the US Critical Illness And Injury Trials Group Lung Injury Prevention Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: A6344.

Merx MW, Liehn EA, Janssens U, Lutticken R, Schrader J, Hanrath P, Weber C: HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin profoundly improves survival in a murine model of sepsis. Circulation 2004, 109: 2560-2565. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129774.09737.5B

Pruefer D, Makowski J, Schnell M, Buerke U, Dahm M, Oelert H, Sibelius U, Grandel U, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Meyer J, Darius H, Buerke M: Simvastatin inhibits inflammatory properties of Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin. Circulation 2002, 106: 2104-2110. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000034048.38910.91

Ando H, Takamura T, Ota T, Nagai Y, Kobayashi K: Cerivastatin improves survival of mice with lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000, 294: 1043-1046.

Jacobson JR, Barnard JW, Grigoryev DN, Ma SF, Tuder RM, Garcia JG: Simvastatin attenuates vascular leak and inflammation in murine inflammatory lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005, 288: L1026-1032.

Pirat A, Zeyneloglu P, Aldemir D, Yucel M, Ozen O, Candan S, Arslan G: Pretreatment with simvastatin reduces lung injury related to intestinal ischemia-reperfusion in rats. Anesth Analg 2006, 102: 225-232. 10.1213/01.ane.0000189554.41095.98

Merx MW, Liehn EA, Graf J, van de Sandt A, Schaltenbrand M, Schrader J, Hanrath P, Weber C: Statin treatment after onset of sepsis in a murine model improves survival. Circulation 2005, 112: 117-124. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.502195

Karaca I, Ilkay E, Akbulut M, Yavuzkir M, Pekdemir M, Akbulut H, Arslan N: Atorvastatin affects C-reactive protein levels in patients with coronary artery disease. Curr Med Res Opin 2003, 19: 187-191. 10.1185/030079903125001686

Kinlay S, Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Rifai N, Leslie SJ, Sasiela WJ, Szarek M, Libby P, Ganz P: High-dose atorvastatin enhances the decline in inflamatory markers in patients with acute coronary syndromes in the MIRACL study. Circulation 2003, 108: 1560-1566. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091404.09558.AF

Laufs U, Wassmann S, Hilgers S, Ribaudo N, Bohm M, Nickenig G: Rapid effects on vascular function after initiation and withdrawal of atorvastatin in healthy, normocholesterolemic men. Am J Cardiol 2001, 88: 1306-1307. 10.1016/S0002-9149(01)02095-1

van de Ree MA, Huisman MV, Princen HM, Mein ders AE, Kluft C: Strong decrease of high sensitivity C-reactive protein with high-dose atorvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis 2003, 166: 129-135. 10.1016/S0021-9150(02)00316-7

Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome in Ireland: a prospective audit of epidemiology and management Crit Care 2008, 12: R30. 10.1186/cc6808

Almog Y, Shefer A, Novack V, Maimon N, Bars ki L, Eizinger M, Friger M, Zeller L, Danon A: Prior statin therapy is associated with a decreased rate of severe sepsis. Circulation 2004, 110: 880-885. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138932.17956.F1

Donnino MW, Cocchi MN, Howell M, Clardy P, Talmor D, Cataldo L, Chase M, Al-Marshad A, Ngo L, Shapiro NI: Statin therapy is associated with decreased mortality in patients with infection. Acad Emerg Med 2009, 16: 230-234. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00350.x

Kruger P, Fitzsimmons K, Cook D, Jones M, Nimmo G: Statin therapy is associated with fewer deaths in patients with bacteraemia. Intensive Care Med 2006, 32: 75-79. 10.1007/s00134-005-2859-y

Liappis AP, Kan VL, Rochester CG, Simon GL: The effect of statins on mortality in patients with bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2001, 33: 1352-1357. 10.1086/323334

Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Murray MP, Hil l AT: Prior statin use is associated with improved outcomes in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med 2008, 121: 1002-1007 e1001. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.06.030

Thomsen RW, Riis A, Kornum JB, Christensen S, Johnsen SP, Sorensen HT: Preadmission use of statins and outcomes after hospitalization with pneumonia: population-based cohort study of 29,900 patients. Arch Intern Med 2008, 168: 2081-2087. 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2081

O'Neal HR Jr, Koyama T, Koehler EA, Siew E, Curtis BR, Fremont RD, May AK, Bernard GR, Ware LB: Prehospital statin and aspirin use and the prevalence of severe sepsis and acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2011, 39: 1343-1350. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182120992

Craig TR, Duffy MJ, Shyamsundar M, McDowell C, O'Kane CM, Elborn JS, McAuley DF: A randomized clinical trial of hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase inhibition for acute lung injury (The HARP Study). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: 620-626. 10.1164/rccm.201003-0423OC

Matthay MA, Folkesson HG, Clerici C: Lung e pithelial fluid transport and the resolution of pulmonary edema. Physiol Rev 2002, 82: 569-600.

Khimenko PL, Barnard JW, Moore TM, Wilson P S, Ballard ST, Taylor AE: Vascular permeability and epithelial transport effects on lung edema formation in ischemia and reperfusion. J Appl Physiol 1994, 77: 1116-1121.

McAuley DF, Frank JA, Fang X, Matthay MA: Clinically relevant concentrations of beta2-adrenergic agonists stimulate maximal cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent airspace fluid clearance and decrease pulmonary edema in experimental acid-induced lung injury. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 1470-1476. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000129489.34416.0E

Maris NA, de Vos AF, Dessing MC, Spek CA, Lutter R, Jansen HM, van der Zee JS, Bresser P, van der Poll T: Antiinflammatory effects of salmeterol after inhalation of lipopolysaccharide by healthy volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005, 172: 878-884. 10.1164/rccm.200503-451OC

Atabai K, Ware LB, Snider ME, Koch P, Danie l B, Nuckton TJ, Matthay MA: Aerosolized beta(2)-adrenergic agonists achieve therapeutic levels in the pulmonary edema fluid of ventilated patients with acute respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med 2002, 28: 705-711. 10.1007/s00134-002-1282-x

Manocha S, Gordon AC, Salehifar E, Groshaus H, Walley KR, Russell JA: Inhaled beta-2 agonist salbutamol and acute lung injury: an association with improvement in acute lung injury. Crit Care 2006, 10: R12. 10.1186/cc3971

Perkins GD, McAuley DF, Thickett DR, Gao F: The beta-agonist lung injury trial (BALTI): a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006, 173: 281-287. 10.1164/rccm.200508-1302OC

National Heart and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Matthay MA, Brower RG, Carson S, Douglas IS, Eisner M, Hite D, Holets S, Kallet RH, Liu KD, MacIntyre N, Moss M, Schoenfeld D, Steingrub J, Thompson BT: Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of an aerosolized beta-2 agonist for treatment of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 184: 561-568.

Smith FG, Perkins GD, Gates S, Young D, McAuley DF, Tunnicliffe W, Khan Z, Lamb SE: Effect of intravenous beta-2 agonist treatment on clinical outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome (BALTI-2): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011, 379: 229-235.

Ware LB, Matthay MA: Alveolar fluid clearance is impaired in the majority of patients with acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 163: 1376-1383.

Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thomp son BT, Hayden D, deBoisblanc B, Connors AF Jr, Hite RD, Harabin AL: Comparison of two fluidmanagement strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2006, 354: 2564-2575.

Meduri GU, Headley AS, Golden E, Carson SJ, Umberger RA, Kelso T, Tolley EA: Effect of prolonged methylprednisolone therapy in unresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998, 280: 159-165. 10.1001/jama.280.2.159

Steinberg KP, Hudson LD, Goodman RB, Hough CL, Lanken PN, Hyzy R, Thompson BT, Ancukiewicz M, National Heart and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network: Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids for persistent acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2006, 354: 1671-1684.

Walther S, Jansson I, Berg S, Lennquist S: Pulmonary granulocyte accumulation is reduced by nebulized corticosteroid in septic pigs. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1992, 36: 651-655. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1992.tb03537.x

Walther S, Jansson I, Berg S, Olsson Rex L, Lennquist S: Corticosteroid by aerosol in septic pigs - effects on pulmonary function and oxygen transport. Intensive Care Med 1993, 19: 155-160. 10.1007/BF01720531

Forsgren PE, Modig JA, Dahlback CM, Axelsson BI: Prophylactic treatment with an aerosolized corticosteroid liposome in a porcine model of early ARDS induced by endotoxaemia. Acta Chir Scand 1990, 156: 423-431.

Wang J, Zhang L, Walther SM: Administration of aerosolized terbutaline and budesonide reduces chlorine gas-induced acute lung injury. J Trauma 2004, 56: 850-862. 10.1097/01.TA.0000078689.45384.8B

Jansson AH, Eriksson C, Wang X: Effects of budesonide and N-acetylcysteine on acute lung hyperinflation, inflammation and injury in rats. Vascul Pharmacol 2005, 43: 101-111. 10.1016/j.vph.2005.03.006

Enrique Ortiz-Diaz, Guangxi Li, Daryl Kor, Ognjen Gajic, Ozan Akca, Adebola Adesanya, Jason Hoth, Festic aE: Preadmission use of inhaled corticosteroids is associated with a reduced risk of direct acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Chest 2011, 140: 912A. 10.1378/chest.1110134

Hagiwara S, Iwasaka H, Hidaka S, Hasegawa A , Koga H, Noguchi T: Antagonist of the type-1 ANG II receptor prevents against LPS-induced septic shock in rats. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 1471-1478. 10.1007/s00134-009-1545-x

Hagiwara S, Iwasaka H, Matumoto S, Hidaka S , Noguchi T: Effects of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor on the inflammatory response in in vivo and in vitro models. Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 626-633. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181958d91

Watkins TR, Lemos-Filho LB, Dabbagh O, Chan g SY, Park PK, Gong MN: Use Of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers and clinical outcomes among patients at-risk for acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: A5598.

Hughes DA, Norton R: Vitamin D and respiratory health. Clin Exp Immunol 2009, 158: 20-25. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04001.x

Jeng L, Yamshchikov AV, Judd SE, Blumberg H M, Martin GS, Ziegler TR, Tangpricha V: Alterations in vitamin D status and anti-microbial peptide levels in patients in the intensive care unit with sepsis. J Transl Med 2009, 7: 28. 10.1186/1479-5876-7-28

Lucidarme O, Messai E, Mazzoni T, Arcade M, du Cheyron D: Incidence and risk factors of vitamin D deficiency in critically ill patients: results from a prospective observational study. Intensive Care Med 2010, 36: 1609-1611. 10.1007/s00134-010-1875-8

Barnett N, Koyama T, Janz DR, May AK, Berna rd GR, Ware LB: Vitamin D deficiency does not modulate the risk of acute lung injury: a case control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: A5596.

Ware LB, Matthay MA, Parsons PE, Thompson B T, Januzzi JL, Eisner MD: Pathogenetic and prognostic significance of altered coagulation and fibrinolysis in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 1821-1828. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000221922.08878.49

Liu KD, Levitt J, Zhuo H, Kallet RH, Brady S, Steingrub J, Tidswell M, Siegel MD, Soto G, Peterson MW, Chesnutt MS, Phillips C, Weinacker A, Thompson BT, Eisner MD, Matthay MA: Randomized clinical trial of activated protein C for the treatment of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008, 178: 618-623. 10.1164/rccm.200803-419OC

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

JEL is a current member of the USCIITG-LIPS investigators and is funded by an NIH/NHLBI career development award (5K23HL091334) to study the early identification and treatment of ALI. MAM is the sponsor for Dr Levitt's NIH/NHLBI career development award (5K23HL091334).

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Levitt, J.E., Matthay, M.A. Clinical review: Early treatment of acute lung injury - paradigm shift toward prevention and treatment prior to respiratory failure. Crit Care 16, 223 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11144

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11144