Abstract

Human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)2 over-expression is associated with a shortened disease-free interval and poor survival. Although the addition of trastuzumab to chemotherapy in the first-line setting has improved response rates, progression-free survival, and overall survival, response rates declined when trastuzumab was used beyond the first-line setting because of multiple mechanisms of resistance. Studies have demonstrated the clinical utility of continuing trastuzumab beyond progression, and further trials to explore this concept are ongoing. New tyrosine kinase inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) pathway regulators, HER2 antibody-drug conjugates, and inhibitors of heat shock protein-90 are being evaluated to determine whether they may have a role to play in treating trastuzumab-resistant metastatic breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As knowledge about the treatment of breast cancer has grown, attention has increasingly focused on developing a targeted approach to this diverse disease. In particular, treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)2/neu-positive breast cancer has undergone significant advances since the cloning of the HER2 oncogene in 1984 [1].

The HER2 oncogene encodes one of four transmembrane receptors within the erbB family. Its over-expression, which occurs in approximately 25% of all breast cancer tumors, is associated with a shortened disease-free interval and poor survival [2]. Following ligand binding, the glycoprotein receptor is activated through homodimerization or heterodimerization, leading to a cascade of events that involves activation of the tyrosine kinase domain, Ras/Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). This sequence promotes the rapid cell growth, differentiation, survival, and migration that are associated with HER2-positive breast cancers (Figure 1). Thus, women with HER2-positive breast cancers exhibit significantly decreased disease-free survival and overall survival (OS) [2–5].

The HER2 family and interrelated signaling and events. The binding of ligands, including epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-α, leads to the activation of signaling cascades involving Ras/Raf/MAPK, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, and JAK/STAT. This sequence of events promotes the apoptosis, proliferation, survival, migration, angiogenesis, and metastasis of HER2-over-expressing breast cancers. BTC, betacellulin; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EPG, epigen; EPR, epiregulin; HB-EGF, heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor; HER, human epidermal growth factor receptor; JAK, Janus kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK, mitogen-induced extracellular kinase; MEKK, mitogen-activated protein/ERK kinase kinase; NRG, neuregulin; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TGF, transforming growth factor; TK, tyrosine kinase.

This review discusses progress in the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer since the discovery of the HER2 oncogene, with particular focus upon the mechanisms of resistance to trastuzumab, treatment with trastuzumab beyond progression, use of lapatinib, and new biologic agents that may provide further therapeutic options in patients with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer.

Use of trastuzumab in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer

Trastuzumab is a humanized recombinant monoclonal anti-body, of the IgG1 type, which binds with high affinity to the extracellular domain of the HER2 receptor. The mechanism underlying trastuzumab's efficacy in the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer is multifaceted and incompletely understood. In vivo breast cancer models have demonstrated that trastuzumab induces antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity through activation of Fc receptor expressing cells (for example, macrophages and natural killer cells), leading to lysis of tumor cells [6, 7]. Trastuzumab has also been shown to downregulate p185ErbB2 [8]. In addition, trastuzumab blocks the release of the extracellular domain of HER2 by inhibiting cleavage of the HER2 protein by ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain) metalloproteinases [9]. Significant declines in serum HER2 levels are a predictor of outcome after trastuzumab-based therapy [10–12]. Furthermore, trastuzumab inhibits downstream PI3K-Akt signaling, leading to apoptosis [13]. It has also been shown that trastuzumab downregulates proteins that are involved in p27kip1 sequestration, causing release of p27kip1 and enabling inhibition of cyclin E/Cdk2 complexes and subsequent G1 arrest [14]. Moreover, trastuzumab has been shown to exert antiangiogenic effects through normalization of microvessel density [15].

Although the mechanism that accounts for trastuzumab's antitumor activity remains incompletely understood and requires further elucidation, the results of the inclusion of trastuzumab in the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer are clear. Slamon and colleagues [16] found that addition of trastuzumab to chemotherapy, in the first-line setting, resulted in a significantly improved objective response, time to disease progression, and OS. Combinations of trastuzumab with taxanes, platinum salts, vinorelbine, and capecitabine have yielded benefits in the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer [17–23]. However, other trials demonstrated that response rates declined markedly when trastuzumab was used beyond the first-line setting, indicating the development of resistance to this agent.

Mechanisms of resistance to trastuzumab

PTEN/PI3K/mTOR/Akt pathways

PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) is a tumor suppressor gene that causes dephosphorylation of phosphotidylinositol-3,4,5 triphosphate, which is the site that recruits the pleckstrinhomology domain of Akt to the cell membrane [24, 25]. PTEN inhibits the ability of PI3K to catalyze the production of phosphotidylinositol-3,4,5 triphosphate and thus antagonizes the Akt cascade [26]. Loss of PTEN function occurs in approximately 50% of all breast cancers [27]. Restoration of PTEN expression impedes Akt activation and increases apoptosis [28]. Nagata and coworkers [24] demonstrated that inhibition of PTEN expression by antisense oligonucleotides resulted in trastuzumab resistance in vitro and in vivo. Specifically, tumors in which PTEN expression was abrogated by antisense oligonucleotides exhibited tumor growth patterns that were unaffected by trastuzumab administration. Patients with PTEN-deficient tumors demonstrated significantly lower complete response (CR) and partial response (PR) rates to trastuzumab plus taxane therapy than those who had PTEN-expressing tumors.

Independent of PTEN mutations, constitutive Akt phosphorylation may also occur in HER2-over-expressing tumors [29].

MUC4 overexpression

MUC4 is a membrane-associated, glycosylated mucin that has been shown to be over-expressed in breast cancer cells [30]. In rat models, MUC4 forms a complex with the HER2 protein and potentiates its phosphorylation, leading to cell proliferation [30, 31]. In addition to its ligand activity, MUC4 inhibits binding of trastuzumab to the HER2 receptor. Utilizing JIMT-1, a HER2-over-expressing cell line with primary resistance to trastuzumab, Nagy and colleagues [32] demonstrated that MUC4 expression was higher in this trastuzumab-resistant cell line than in trastuzumab-sensitive cell lines, and that the level of MUC4 expression inversely correlated with the trastuzumab-binding capacity of single tumor cells. Because the researchers found no mutations in the coding sequence of HER2 in the JIMT-1 cell line, they hypothesized that inhibition of trastuzumab binding was mediated by MUC4-induced masking of the trastuzumab-binding epitope [32].

Truncation of the HER2 receptor

Truncation of the HER2 receptor, as a result of proteolytic shedding of the HER2 extracellular domain or via alternative initiation from methionines located near to the transmembrane domain of the full-length molecule, can yield a 95-kDa fragment [33–35]. The p95HER2 fragment maintains constitutive kinase activity and correlates with poor outcome in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer [35]. This truncated form of HER2 does not possess the extracellular trastuzumab-binding epitope, and its expression has been associated with trastuzumab resistance [36].

Activation of the insulin-like growth factor receptor-1 pathway

The insulin-like growth factor receptor-I (IGF-IR) is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor whose activation is associated with mitogenesis and cell survival [37]. Lu and colleagues [38] showed that trastuzumab was rendered ineffective by genetic alteration of the SKBR3 human breast cancer cell lines to enable IGF-IR over-expression. Subsequently, addition of an IGF-binding protein that reduced IGF-IR signaling restored trastuzumab's ability to inhibit cell growth. Utilizing the SKBR3 cell lines, Nahta and coworkers [39] demonstrated that IGF-I stimulation led to increased phosphorylation of HER2 in trastuzumab-resistant cells but not in parental trastuzumab-sensitive cells. In addition, inhibition of IGF-IR tyrosine activity reduced HER2 phosphorylation only in trastuzumab-resistant cells. Thus, there exists substantial cross-talk between IGF-IR and HER2 in trastuzumab-resistant cells.

Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor

Du Manoir and colleagues [40] compared the levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) protein expression in cell lines that had never been exposed to trastuzumab with those cell lines that had acquired resistance to trastuzumab. They found that VEGF protein expression was increased in three out of four of the resistant cell lines; however, no significant difference in VEGF mRNA expression was present, implying that the increase in VEGF protein expression was mediated by post-transcriptional changes. In addition, when bevacizumab was added to a trastuzumab-based regimen for mice bearing tumors of the 231-H2N cell line, a HER2-over-expressing variant of the MDA-MB-231 cell line, tumor growth was delayed significantly. Their cumulative findings indicate that upregulation of VEGF may contribute to the mechanism of trastuzumab resistance, and dual inhibition of these pathways is currently being studied in phase I trials.

Treatment with trastuzumab beyond progression

Disease progression after treatment with a trastuzumab-based regimen in the first-line metastatic setting is met with two options: continuation of trastuzumab alongside another chemotherapeutic agent that is not cross-resistant, or changing to a completely different (non-trastuzumab-based) regimen. Evidence supporting the former approach first appeared in an extension study, in which patients who had progressed during the pivotal trial of trastuzumab plus chemotherapy were offered further trastuzumab-based treatment [41]. Concurrent chemotherapy was chosen at the discretion of the treating physician. Researchers found that the group of patients who had previously received chemotherapy alone during the pivotal trial had a 14% objective response rate and 32% clinical benefit rate (CR plus PR plus stable disease for ≥ 6 months) during the extension trial. Those who had already received a trastuzumab-based regimen during the pivotal trial had a 11% objective response rate and 22% clinical benefit rate. Median duration of response was greater than 6 months in both groups. These findings suggest that trastuzumab continues to demonstrate clinical utility in the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer beyond progression. Four retrospective studies have corroborated these results.

Stemmler and coworkers [42] found that patients who received two or more trastuzumab-based regimens had a significantly longer OS than did those who received only one regimen (62.4 months versus 38.5 months; P = 0.01), indicating that use of trastuzumab beyond progression is a valid option in this group of patients. In addition, the Hermine retrospective cohort study [43] demonstrated that, when compared with patients who discontinued trastuzumab upon progression of disease, those who continued to receive a trastuzumab-based regimen beyond progression exhibited an improvement both in time to progression (TTP) and in median OS. Another study, conducted by Gelmon and colleagues [44], revealed that overall response rate to trastuzumab alone or with a taxane as the first regimen was 39%; a further 30% of patients had stable disease as the best response. These rates declined only slightly (36% and 38% for overall response rate and stable disease, respectively) after a second regimen of trastuzumab (alone or in combination with paclitaxel or vinorelbine) was administered. Patients who received further trastuzumab-based regimens beyond disease progression demonstrated a significant improvement in OS when compared with those who received only one trastuzumab-based regimen (38.5 months versus 62.4 months; P = 0.01).

A fourth study – a retrospective analysis of 101 patients who continued to receive a trastuzumab-containing regimen beyond progression – was reported this year [45]. It demonstrated a trend toward improvement in response rates (35% versus 16%) and median OS rates (70 months versus 56 months) in the patients who continued on trastuzumab, but the findings were not statistically significant.

Although the results of these retrospective studies are encouraging, these analyses suffer from the inherent limitations of retrospective chart review, lack of uniformity in chemotherapy choice, and evaluation of adverse events in only the retrospective setting [46].

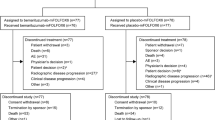

Recently, interim results from three prospective trials were reported that support the use of trastuzumab beyond disease progression on a trastuzumab-based regimen [47]. Bachlot and colleagues [48] presented the results of a phase II trial that evaluated the response rate to second-line treatment with the combination of trastuzumab and vinorelbine, after progression of disease on a first-line regimen of trastuzumab plus taxane. They found that the overall response rate in this second-line setting was 29%, with two patients showing a CR. Furthermore, von Minckwitz and coworkers [49] presented the results of the TBP (Treatment Beyond Progression) trial, in which women who had progressed while on a trastuzumab-based regimen were randomly assigned to treatment with capecitabine monotherapy or capecitabine plus trastuzumab. The women who received both capecitabine and trastuzumab demonstrated an improvement in TTP (33 weeks versus 24 weeks), although this finding was not statistically significant (P = 0.178). O'Shaughnessy and colleagues [50] conducted a randomized phase III trial of lapatinib versus lapatinib plus trastuzumab in heavily pre-treated patients who had progressed after trastuzumab-based therapy. In this study, the TTP was improved in patients treated with trastuzumab plus lapatinib (P = 0.029).

Given the importance of this issue, two other randomized phase III trials are poised to address the use of trastuzumab beyond progression: THOR (Trastuzumab Halted or Retained) and Pandora. The THOR and Pandora trials are phase III trials that will randomly assign patients, who progressed on a first-line regimen of trastuzumab plus chemotherapy, to continue or discontinue trastuzumab while receiving a second-line chemotherapy of the investigator's choice.

New agents in the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer

Since the identification of the HER2 oncogene, development of new agents targeting the HER2 pathway has led to significant improvement in the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (Table 1).

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Lapatinib

Lapatinib is an orally bioavailable, small-molecule dual inhibitor of the tyrosine kinase activity of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and HER2. It reversibly binds to the cytoplasmic ATP-binding site of the intracellular tyrosine kinase, preventing receptor phosphorylation and downstream signaling of several pathways, including Akt and MAPK [51]. Its targeting of the kinase domain of HER2 enables this agent to retain activity in trastuzumab-resistant tumor cells that over-express the truncated HER2 receptor (p95HER2). Treatment of p95HER2-expressing cells with lapatinib has been shown to reduce p95HER2 phosphorylation, impede downstream activation of Akt and MAPK, and inhibit cell proliferation [36]. In addition, an analysis of the tumor samples of 46 patients with metastatic breast cancer who were treated with trastuzumab demonstrated that only one out of nine patients who expressed p95HER2 responded to trastuzumab, whereas 19 of the 37 patients with tumors expressing full-length HER2 achieved either a CR or a PR (P = 0.029) [36]. These findings indicate that there may be a role for lapatinib, or another tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in the treatment of p95HER2-related trastuzumab resistance.

The preclinical studies of lapatinib eventually led to a pivotal phase III trial that involved patients with HER2-positive advanced or metastatic breast cancer who had progressed after treatment with a regimen that included an anthracycline, a taxane, and trastuzumab [52]. The study randomly assigned these patients to receive treatment with capecitabine monotherapy versus lapatinib plus capecitabine, and an interim analysis demonstrated that the combination of lapatinib plus capecitabine yielded a significant improvement in TTP (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.49; one-sided P = 0.00016). However, it should be noted that OS was equivalent in the treatment arms. Researchers noted a trend toward improvement in the occurrence of cerebral nervous system metastases in the combination group. Updated results of this trial confirmed the improved TTP due to the combination of lapatinib plus capecitabine (27 weeks versus 19 weeks), with a HR of 0.57 (P = 0.00013) [53]. Furthermore, the updated findings demonstrated a trend toward an improvement in OS, although this result was not statistically significant (HR = 0.78, P = 0.177). The results of this trial led to the US Food and Drug Administration's approval of lapatinib, in combination with capecitabine, in the treatment of patients with advanced or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer that progressed after trastuzumab, anthracyclines, and taxanes.

A recent phase III trial randomly assigned patients with metastatic breast cancer, which was negative or untested for HER2, to receive first-line treatment with paclitaxel monotherapy versus paclitaxel and lapatinib [54]. Overall, the study found no significant difference in TTP, event-free survival, or OS with the addition of lapatinib to paclitaxel therapy. However, in a planned subgroup analysis, the authors found that – among patients who were HER2 positive – the addition of lapatinib to paclitaxel resulted in significant improvements in TTP (HR = 0.53; P = 0.005) and event-free survival (HR = 0.52; P = 0.004). In these HER2-positive patients, OS was also increased in the paclitaxellapatinib arm, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.365). These findings support further studies exploring the use of lapatinib-based regimens in the first-line treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer.

Based upon preclinical data indicating that the combination of trastuzumab and lapatinib may produce synergistic inhibition of cell proliferation, a phase I study involving this combination was conducted in patients with advanced or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer [55, 56]. The most frequent drug-related grade 3 events were diarrhea (17%), fatigue (11%), and rash (6%). The combination regimen resulted in one CR and seven PRs. All eight responders had received prior trastuzumab therapy in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy. Furthermore, six patients had stable disease for longer than 6 months. Because of these encouraging results, a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study was initiated to determine whether the addition of lapatinib to a combination of trastuzumab and paclitaxel will render an improvement in TTP [57]. This trial will also evaluate the incidence of central nervous system metastases among these groups, given the encouraging findings in the previous pivotal trial, in order to investigate further the hypothesis that the small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors, unlike the monoclonal antibodies, may be able to cross the blood-brain barrier effectively.

HKI-272

HKI-272 is a potent and irreversible inhibitor of the tyrosine kinase domains of EGFR and HER2, resulting in arrest at the G1-S (Gap 1/DNA synthesis) phase [58]. Preliminary results of an open-label, phase II study involving HKI-272 in the treatment of women with advanced or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer [59] revealed six confirmed PRs, as well as additional patients with unconfirmed PRs. Diarrhea was the only grade 3 to 4 treatment-related adverse event that occurred in more than one patient. This trial continues to accrue patients.

Gefitinib and erlotinib

Gefitinib and erlotinib are small-molecule EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Previous preclinical studies have been contradictory. For example, in one study [60] the combination of gefitinib and trastuzumab resulted in a synergistic inhibition of the SK-Br-3 and BT-474 breast carcinoma cell lines, both of which express EGFR and ErbB-2. However, these findings were not confirmed in breast cancer xenograft models, which demonstrated that gefitinib did not further reduce tumor cell viability in trastuzumab-treated tumors [61]. In phase II clinical trials of single-agent gefitinib and single-agent erlotinib, the response rates were less than 5% [62]. A phase I/II trial was conducted in which patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer who had previously received between 0 to 2 chemotherapy regimens were treated with a combination of trastuzumab (2 mg/kg per week) and gefitinib (250 to 500 mg/day). Within the chemotherapy-naïve group, one CR, one PR, and seven instances of stable disease were reported. However, no responses were seen among patients who had previously been treated. Thus, at the time of the interim analysis, the TTP did not meet predetermined statistical end-points required for study continuation, and the study was halted [63]. Moreover, the abbreviated TTP (2.5 to 2.9 months) observed in this trial suggests a possible antagonistic interaction between gefitinib and trastuzumab.

Pazopanib

Pazopanib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of VEGF receptor-1, -2 and -3, platelet-derived growth factor-α and -β, and c-kit. A phase I study evaluating the use of pazopanib in various solid tumors demonstrated that the agent was well tolerated [64]. Preliminary efficacy results revealed a minimal response in four patients; six other patients exhibited stable disease for longer than 6 months. Based upon encouraging preclinical data supporting the combination of lapatinib and pazopanib, a phase I open-label trial involving 33 patients with solid tumors was initiated [65]. It demonstrated that 10 patients experienced stable disease for longer than 16 weeks, and three patients had PRs. Thus, a phase II, open-label randomized trial began in 2006 and is ongoing. This study randomly assigned patients to receive treatment with lapatinib plus pazopanib, versus lapatinib alone, in the first-line treatment of advanced or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer [66, 67]. Preliminary efficacy results revealed that the progressive disease rate was 69% in the combination group versus 27% in the lapatinib monotherapy group.

Monoclonal antibodies

Pertuzumab

Pertuzumab is an IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to HER2 at the dimerization domain, sterically preventing heterodimerization [68, 69]. The pertuzumab-binding site does not overlap with the trastuzumab epitope on HER2 [70, 71]. Preclinical studies demonstrated that trastuzumab and pertuzumab synergistically inhibited the survival of BT474 cells, reduced levels of total and phosphorylated HER2 protein, and blocked receptor signaling through Akt [72]. A phase I dose escalation study of pertuzumab in 21 patients with advanced cancers showed that pertuzumab was well tolerated and led to a partial response in two patients and stable disease in six patients [73]. Thus, a single-arm, two-stage phase II trial, involving patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer who had received up to three lines of prior therapy and had developed disease progression during trastuzumab-based therapy, is in progress. Interim results revealed that, among the 33 evaluable patients, one CR and five PRs had occurred [74, 75]. In addition, seven patients exhibited stable disease for longer than 6 months, and 10 patients had stable disease for less than 6 months. Recruitment into the second stage of this study is ongoing.

Bevacizumab

Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody to VEGF, which was approved this year by the US Food and Drug Administration to be used in combination with paclitaxel for the treatment of metastatic HER2-negative breast cancer. Encouraging pre-clinical studies demonstrated the benefit of adding bevacizumab to trastuzumab, as compared with treatment with trastuzumab alone, in order to inhibit tumor growth further in a breast cancer xenograft model [40]. A phase I, open-label, dose-escalation trial assessed the optimal dose schedule and safety of bevacizumab in combination with trastuzumab [76]. The study showed that co-administration of these agents did not alter the pharmacokinetics of either drug, and no grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurred. Preliminary efficacy results showed one CR, four PRs, and two patients with stable disease among nine evaluable patients.

Based upon these encouraging results, a phase II extension study was initiated to evaluate the efficacy of this combination in the first-line treatment of patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Of the 37 patients who were evaluated in this trial, preliminary findings demonstrated one CR and 19 PRs; the combination of bevacizumab and trastuzumab without chemotherapy produced an overall response rate of 54%. Furthermore, a phase III study has been initiated that will randomly assign patients to receive either bevacizumab and trastuzumab and docetaxel, versus trastuzumab plus docetaxel [77]. The primary end-point of this study will be progression-free survival; secondary outcome measures will include OS, best overall response, duration of response, time to treatment failure, quality of life, and cardiac safety.

Regulators of the PTEN/P13K/mTOR/Akt pathways

Everolimus is a macrolide that selectively inhibits mTOR. Because PTEN deficiency, which occurs in approximately 50% of all breast cancers, leads to constitutive activation of Akt and subsequent activation of mTOR, inhibitors of mTOR add potential additive benefit to biologic or chemotherapy. Preclinical testing demonstrated that, after the breast cancer cell line BT474M1 was rendered PTEN deficient and trastuzumab resistant through transfection with PTEN anti-sense oligonucleotides, the combination of RAD001 and the Akt inhibitor triciribine restored trastuzumab sensitivity and markedly increased growth inhibition by trastuzumab [78]. A phase I/II trial, involving the use of RAD001 in combination with trastuzumab for the treatment of patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer that has progressed on trastuzumab-based therapy, is ongoing at our institution.

HER2 antibody-drug conjugates

Trastuzumab-DM1 is a novel HER2 antibody-drug conjugate in which trastuzumab is chemically linked to a highly potent maytansine-derived antimicrotubule drug (DM1). Xenograft models have established the efficacy of this compound in both trastuzumab-sensitive and trastuzumab-resistant breast tumors [79]. Recently, the results of a phase II trial involving trastuzumab-DM1 in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer that had progressed on HER2-directed therapy (trastuzumab, lapatinib, or both) were presented [80]. Twenty-five percent of patients demonstrated a confirmed objective response, and 35% of patient demonstrated clinical benefit, which consisted of either a confirmed objective response or stable disease lasting for at least 6 months.

Inhibitors of heat shock protein-90

The heat shock protein-90 is a chaperone protein that enables the proper folding of newly synthesized client proteins, such as HER2, into a stable tertiary conformation. Geldanamycin, an ansamycin antibiotic, was first isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus and noted to have inhibitory activity against heat shock protein-90 [81, 82]. However, because of geldamycin's narrow therapeutic widow, 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) was derived from the initial compound [82]. Preclinical studies involving 17-AAG revealed that it reduced cellular proliferation of the trastuzumab-resistant cell line JIMT-1 [83]. The antiproliferative effect of 17-AAG was positively correlated with phosphorylation and downregulation of HER2, and was dominated by apoptosis. Thus, a phase I dose-escalation study was initiated, in which patients with advanced solid tumors who had progressed during standard therapy were treated with weekly trastuzumab followed by intravenous tanespimycin (17-AAG). Among the 25 patients enrolled, one PR, four minor responses, and four patients with stable disease were noted [84]. The authors observed that tumor regressions were seen only in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer.

Economic implications of targeted therapy

Unfortunately, most countries experience economic pressures on health care, resulting in the need to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of utilizing targeted therapy for the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Specifically, trastuzumab is being closely studied in this setting. Norum and colleagues [85] conducted a cost-effectiveness study in which they reviewed cost per life year in clinical trials involving chemotherapy with or without trastuzumab. They found that the cost per life year saved with the use of trastuzumab ranged between €63,137 and €162,417, depending on survival gain and discount rate employed. However, this study has been criticized for its failure to account for the ability of trastuzumab to reduce the incidence, and thus the cost of treatment, of relapses [86]. A French open-control study evaluated the cost-effectiveness ratio of trastuzumab in combination with paclitaxel when compared with conventional chemotherapy [87]. This study found that the additional cost per saved year of life of trastuzumab, expressed as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, was €15,370. Although this figure may be acceptable in a developed country that has adequate resources, the Breast Health Global Initiative Therapy Focus Group has noted that the price of monoclonal antibodies may exceed the resources of low-resource countries [88].

Conclusions

In the years that have intervened since the discovery of the HER2 oncogene, the use of trastuzumab has revolutionized the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer. However, as the success of trastuzumab has grown, its limitations have become apparent in a parallel manner. Although mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance have been described, a complete understanding of these pathways requires elucidation of the interactions within and between their members. Multifaceted novel strategies that target these alternative pathways are necessary to overcome the adaptive mechanisms of this genetically diverse population and thus increase the likelihood of establishing lasting antitumor efficacy.

Abbreviations

- 17-AAG:

-

17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin

- CR:

-

complete response

- EGFR:

-

epidermal growth factor receptor

- HER:

-

human epidermal growth factor receptor

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- IGF-IR:

-

insulin-like growth factor receptor-I

- MAPK:

-

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- mTOR:

-

mammalian target of rapamycin

- OS:

-

overall survival

- PI3K:

-

phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- PR:

-

partial response

- PTEN:

-

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- TTP:

-

time to progression

- VEGF:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor.

References

Schechter AL, Stern DF, Vaidyanathan L, Decker SJ, Drebin JA, Greene MI, Weinberg RA: The neu oncogene: an erb-B-related gene encoding a 185,000-Mr tumour antigen. Nature. 1984, 312: 513-516. 10.1038/312513a0.

Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL: Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987, 235: 177-182. 10.1126/science.3798106.

Slamon DJ, Godolphin W, Jones LA, Holt JA, Wong SG, Keith DE, Levin WJ, Stuart SG, Udove J, Ullrich A, et al: Studies of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in human breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1989, 244: 707-712. 10.1126/science.2470152.

Seshadri R, Firgaira FA, Horsfall DJ, McCaul K, Setlur V, Kitchen P: Clinical significance of HER-2/neu oncogene amplification in primary breast cancer. The South Australian Breast Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1993, 11: 1936-1942.

Ravdin PM, Chamness GC: The c-erbB-2 proto-oncogene as a prognostic and predictive marker in breast cancer: a paradigm for the development of other macromolecular markers – a review. Gene. 1995, 159: 19-27. 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00866-Q.

Gennari R, Menard S, Fagnoni F, Ponchio L, Scelsi M, Tagliabue E, Castiglioni F, Villani L, Magalotti C, Gibelli N, Oliviero B, Ballardini B, Da Prada G, Zambelli A, Costa A: Pilot study of the mechanism of action of preoperative trastuzumab in patients with primary operable breast tumors overexpressing HER2. Clin Cancer Res. 2004, 10: 5650-5655. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0225.

Cooley S, Burns LJ, Repka T, Miller JS: Natural killer cell cytotoxicity of breast cancer targets is enhanced by two distinct mechanisms of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against LFA-3 and HER2/neu. Exp Hematol. 1999, 27: 1533-1541. 10.1016/S0301-472X(99)00089-2.

Hudziak RM, Lewis GD, Winget M, Fendly BM, Shepard HM, Ullrich A: p185HER2 monoclonal antibody has antiproliferative effects in vitro and sensitizes human breast tumor cells to tumor necrosis factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1989, 9: 1165-1172.

Molina MA, Codony-Servat J, Albanell J, Rojo F, Arribas J, Baselga J: Trastuzumab (herceptin), a humanized anti-Her2 receptor monoclonal antibody, inhibits basal and activated Her2 ectodomain cleavage in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001, 61: 4744-4749.

Bethune-Volters A, Labroquere M, Guepratte S, Hacene K, Neumann R, Carney W, Pichon MF: Longitudinal changes in serum HER-2/neu oncoprotein levels in trastuzumab-treated metastatic breast cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 2004, 24: 1083-1089.

Esteva FJ, Cheli CD, Fritsche H, Fornier M, Slamon D, Thiel RP, Luftner D, Ghani F: Clinical utility of serum HER2/neu in monitoring and prediction of progression-free survival in metastatic breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab-based therapies. Breast Cancer Res. 2005, 7: R436-R443. 10.1186/bcr1020.

Fornier MN, Seidman AD, Schwartz MK, Ghani F, Thiel R, Norton L, Hudis C: Serum HER2 extracellular domain in metastatic breast cancer patients treated with weekly trastuzumab and paclitaxel: association with HER2 status by immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization and with response rate. Ann Oncol. 2005, 16: 234-239. 10.1093/annonc/mdi059.

Yakes FM, Chinratanalab W, Ritter CA, King W, Seelig S, Arteaga CL: Herceptin-induced inhibition of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and Akt Is required for antibody-mediated effects on p27, cyclin D1, and antitumor action. Cancer Res. 2002, 62: 4132-4141.

Lane HA, Motoyama AB, Beuvink I, Hynes NE: Modulation of p27/Cdk2 complex formation through 4D5-mediated inhibition of HER2 receptor signaling. Ann Oncol. 2001, 12 (suppl 1): S21-22. 10.1023/A:1011155606333.

Klos KS, Zhou X, Lee S, Zhang L, Yang W, Nagata Y, Yu D: Combined trastuzumab and paclitaxel treatment better inhibits ErbB-2-mediated angiogenesis in breast carcinoma through a more effective inhibition of Akt than either treatment alone. Cancer. 2003, 98: 1377-1385. 10.1002/cncr.11656.

Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, Fleming T, Eiermann W, Wolter J, Pegram M, Baselga J, Norton L: Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001, 344: 783-792. 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101.

Burstein HJ, Harris LN, Marcom PK, Lambert-Falls R, Havlin K, Overmoyer B, Friedlander RJ, Gargiulo J, Strenger R, Vogel CL, Ryan PD, Ellis MJ, Nunes RA, Bunnell CA, Campos SM, Hallor M, Gelman R, Winer EP: Trastuzumab and vinorelbine as first-line therapy for HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer: multicenter phase II trial with clinical outcomes, analysis of serum tumor markers as predictive factors, and cardiac surveillance algorithm. J Clin Oncol. 2003, 21: 2889-2895. 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.018.

Esteva FJ, Valero V, Booser D, Guerra LT, Murray JL, Pusztai L, Cristofanilli M, Arun B, Esmaeli B, Fritsche HA, Sneige N, Smith TL, Hortobagyi GN: Phase II study of weekly docetaxel and trastuzumab for patients with HER-2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002, 20: 1800-1808. 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.058.

Fountzilas G, Tsavdaridis D, Kalogera-Fountzila A, Christodoulou CH, Timotheadou E, Kalofonos CH, Kosmidis P, Adamou A, Papakostas P, Gogas H, Stathopoulos G, Razis E, Bafaloukos D, Skarlos D: Weekly paclitaxel as first-line chemotherapy and trastuzumab in patients with advanced breast cancer. A Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2001, 12: 1545-1551. 10.1023/A:1013184301155.

Pegram MD, Pienkowski T, Northfelt DW, Eiermann W, Patel R, Fumoleau P, Quan E, Crown J, Toppmeyer D, Smylie M, Riva A, Blitz S, Press MF, Reese D, Lindsay MA, Slamon DJ: Results of two open-label, multicenter phase II studies of docetaxel, platinum salts, and trastuzumab in HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004, 96: 759-769.

Perez EA, Suman VJ, Rowland KM, Ingle JN, Salim M, Loprinzi CL, Flynn PJ, Mailliard JA, Kardinal CG, Krook JE, Thrower AR, Visscher DW, Jenkins RB: Two concurrent phase II trials of paclitaxel/carboplatin/trastuzumab (weekly or every-3-week schedule) as first-line therapy in women with HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer: NCCTG study 983252. Clin Breast Cancer. 2005, 6: 425-432. 10.3816/CBC.2005.n.047.

Robert N, Leyland-Jones B, Asmar L, Belt R, Ilegbodu D, Loesch D, Raju R, Valentine E, Sayre R, Cobleigh M, Albain K, McCullough C, Fuchs L, Slamon D: Randomized phase III study of trastuzumab, paclitaxel, and carboplatin compared with trastuzumab and paclitaxel in women with HER-2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006, 24: 2786-2792. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.1764.

Schaller G, Fuchs I, Gonsch T, Weber J, Kleine-Tebbe A, Klare P, Hindenburg HJ, Lakner V, Hinke A, Bangemann N: Phase II study of capecitabine plus trastuzumab in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 overexpressing metastatic breast cancer pretreated with anthracyclines or taxanes. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25: 3246-3250. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6826.

Nagata Y, Lan KH, Zhou X, Tan M, Esteva FJ, Sahin AA, Klos KS, Li P, Monia BP, Nguyen NT, Hortobagyi GN, Hung MC, Yu D: PTEN activation contributes to tumor inhibition by trastuzumab, and loss of PTEN predicts trastuzumab resistance in patients. Cancer Cell. 2004, 6: 117-127. 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.022.

Parsons R, Simpson L: PTEN and cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2003, 222: 147-166.

Cantley LC: The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002, 296: 1655-1657. 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655.

Pandolfi PP: Breast cancer: loss of PTEN predicts resistance to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2004, 351: 2337-2338. 10.1056/NEJMcibr043143.

Lu Y, Lin YZ, LaPushin R, Cuevas B, Fang X, Yu SX, Davies MA, Khan H, Furui T, Mao M, Zinner R, Hung MC, Steck P, Siminovitch K, Mills GB: The PTEN/MMAC1/TEP tumor suppressor gene decreases cell growth and induces apoptosis and anoikis in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 1999, 18: 7034-7045. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203183.

Clark AS, West K, Streicher S, Dennis PA: Constitutive and inducible Akt activity promotes resistance to chemotherapy, trastuzumab, or tamoxifen in breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002, 1: 707-717.

Price-Schiavi SA, Jepson S, Li P, Arango M, Rudland PS, Yee L, Carraway KL: Rat Muc4 (sialomucin complex) reduces binding of anti-ErbB2 antibodies to tumor cell surfaces, a potential mechanism for herceptin resistance. Int J Cancer. 2002, 99: 783-791. 10.1002/ijc.10410.

Komatsu M, Jepson S, Arango ME, Carothers Carraway CA, Carraway KL: Muc4/sialomucin complex, an intramembrane modulator of ErbB2/HER2/Neu, potentiates primary tumor growth and suppresses apoptosis in a xenotransplanted tumor. Oncogene. 2001, 20: 461-470. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204106.

Nagy P, Friedlander E, Tanner M, Kapanen AI, Carraway KL, Isola J, Jovin TM: Decreased accessibility and lack of activation of ErbB2 in JIMT-1, a herceptin-resistant, MUC4-expressing breast cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 2005, 65: 473-482.

Anido J, Scaltriti M, Bech Serra JJ, Santiago Josefat B, Todo FR, Baselga J, Arribas J: Biosynthesis of tumorigenic HER2 C-terminal fragments by alternative initiation of translation. EMBO J. 2006, 25: 3234-3244. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601191.

Molina MA, Sáez R, Ramsey EE, Garcia-Barchino MJ, Rojo F, Evans AJ, Albanell J, Keenan EJ, Lluch A, García-Conde J, Baselga J, Clinton GM: NH2-terminal truncated HER-2 protein but not full-length receptor is associated with nodal metastasis in human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002, 8: 347-353.

Saez R, Molina MA, Ramsey EE, Rojo F, Keenan EJ, Albanell J, Lluch A, Garcia-Conde J, Baselga J, Clinton GM: p95HER-2 predicts worse outcome in patients with HER-2-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006, 12: 424-431. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1807.

Scaltriti M, Rojo F, Ocaña A, Anido J, Guzman M, Cortes J, Di Cosimo S, Matias-Guiu X, Ramon y Cajal S, Arribas J, Baselga J: Expression of p95HER2, a truncated form of the HER2 receptor, and response to anti-HER2 therapies in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007, 99: 628-638. 10.1093/jnci/djk134.

O'Connor R, Fennelly C, Krause D: Regulation of survival signals from the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000, 28: 47-51.

Lu Y, Zi X, Zhao Y, Mascarenhas D, Pollak M: Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling and resistance to trastuzumab (Herceptin). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001, 93: 1852-1857. 10.1093/jnci/93.24.1852.

Nahta R, Yuan LX, Zhang B, Kobayashi R, Esteva FJ: Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterodimerization contributes to trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005, 65: 11118-11128. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3841.

du Manoir JM, Francia G, Man S, Mossoba M, Medin JA, Viloria-Petit A, Hicklin DJ, Emmenegger U, Kerbel RS: Strategies for delaying or treating in vivo acquired resistance to trastuzumab in human breast cancer xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2006, 12: 904-916. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1109.

Tripathy D, Slamon DJ, Cobleigh M, Arnold A, Saleh M, Mortimer JE, Murphy M, Stewart SJ: Safety of treatment of metastatic breast cancer with trastuzumab beyond disease progression. J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22: 1063-1070. 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.557.

Stemmler HJ, Kahlert S, Siekiera W, Untch M, Heinrich B, Heinemann V: Prolonged survival of patients receiving trastuzumab beyond disease progression for HER2 overexpressing metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Onkologie. 2005, 28: 582-586. 10.1159/000088296.

Extra J-M, Antoine E-C, Vincent-Salomon A, Bergougnoux L, Campana F, Namer M: Favourable effect of continued trastuzumab treatment in metastatic breast cancer patients: results from the French Hermine cohort study [abstract 2064]. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006, 100 (suppl 1): S102-

Gelmon KA, Mackey J, Verma S, Gertler SZ, Bangemann N, Klimo P, Schneeweiss A, Bremer K, Soulieres D, Tonkin K, Bell R, Heinrich B, Grenier D, Dias R: Use of trastuzumab beyond disease progression: observations from a retrospective review of case histories. Clin Breast Cancer. 2004, 5: 52-58. 10.3816/CBC.2004.n.010. discussion 59–62.

Cancello G, Montagna E, D'Agostino D, Giuliano M, Giordano A, Di Lorenzo G, Plaitano M, De Placido S, De Laurentiis M: Continuing trastuzumab beyond disease progression: outcomes analysis in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2008, 10: R60-10.1186/bcr2119.

Pusztai L, Esteva FJ: Continued use of trastuzumab (herceptin) after progression on prior trastuzumab therapy in HER-2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Invest. 2006, 24: 187-191. 10.1080/07357900500524629.

Spector N: Treatment of metastatic ErbB2-positive breast cancer: options after progression on trastuzumab. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008, 8 (suppl 3): S94-S99. 10.3816/CBC.2008.s.005.

Bachelot TML, Delcambre C, Maillart P, Veyret C, Mouret-Reynier M, Van Praagh I, Chollet P: Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab plus vinorelbine as second-line treatment for women with HER-2 positive metastatic breast cancer beyond disease progression [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25 (suppl): 1094-

Von Minckwitz G, Vogel P, Schmidt M, Eidtmann H, Cufer T, De Jongh F, Maartense E, Zielinski C, Andersson M, Stein R, Nekljudova V, Loibl S: Trastuzumab treatment beyond progression in patients with HER-2 positive metastatic breast cancer: the TBP study (GBG 26/BIG 3-05). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007, 106: S185-4056.

O'Shaughnessy J, Blackwell KL, Burstein H, Storniolo AM, Sledge G, Baselga J, Koehler M, Laabs S, Florance A, Roychowdhury D: A randomized study of lapatinib alone or in combination with trastuzumab in heavily pretreated HER2+ metastatic breast cancer progressing on trastuzumab therapy [abstract 1015]. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26 (suppl): 154s-

Rusnak DW, Affleck K, Cockerill SG, Stubberfield C, Harris R, Page M, Smith KJ, Guntrip SB, Carter MC, Shaw RJ, Jowett A, Stables J, Topley P, Wood ER, Brignola PS, Kadwell SH, Reep BR, Mullin RJ, Alligood KJ, Keith BR, Crosby RM, Murray DM, Knight WB, Gilmer TM, Lackey K: The characterization of novel, dual ErbB-2/EGFR, tyrosine kinase inhibitors: potential therapy for cancer. Cancer Res. 2001, 61: 7196-7203.

Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, Chan S, Romieu CG, Pienkowski T, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A, Crown J, Chan A, Kaufman B, Skarlos D, Campone M, Davidson N, Berger M, Oliva C, Rubin SD, Stein S, Cameron D: Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355: 2733-2743. 10.1056/NEJMoa064320.

Cameron D, Casey M, Press M, Lindquist D, Pienkowski T, Romieu CG, Chan S, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A, Kaufman B, Crown J, Chan A, Campone M, Viens P, Davidson N, Gorbounova V, Raats JI, Skarlos D, Newstat B, Roychowdhury D, Paoletti P, Oliva C, Rubin S, Stein S, Geyer CE: A phase III randomized comparison of lapatinib plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in women with advanced breast cancer that has progressed on trastuzumab: updated efficacy and biomarker analyses. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008, 112: 533-543. 10.1007/s10549-007-9885-0.

Di Leo A, Gomez HL, Aziz Z, Zvirbule Z, Bines J, Arbushites MC, Guerrera SF, Koehler M, Oliva C, Stein SH, Williams LS, Dering J, Finn RS, Press MF: Phase III, double-blind, randomized study comparing lapatinib plus paclitaxel with placebo plus paclitaxel as first-line treatment for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26: 5544-5552. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2578.

Konecny GE, Pegram MD, Venkatesan N, Finn R, Yang G, Rahmeh M, Untch M, Rusnak DW, Spehar G, Mullin RJ, Keith BR, Gilmer TM, Berger M, Podratz KC, Slamon DJ: Activity of the dual kinase inhibitor lapatinib (GW572016) against HER-2-overexpressing and trastuzumab-treated breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006, 66: 1630-1639. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1182.

Storniolo AM, Pegram MD, Overmoyer B, Silverman P, Peacock NW, Jones SF, Loftiss J, Arya N, Koch KM, Paul E, Pandite L, Fleming RA, Lebowitz PF, Ho PT, Burris HA: Phase I dose escalation and pharmacokinetic study of lapatinib in combination with trastuzumab in patients with advanced ErbB2-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26: 3317-3323. 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5202.

Clinical Trials Database. [http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00667251]

Rabindran SK, Discafani CM, Rosfjord EC, Baxter M, Floyd MB, Golas J, Hallett WA, Johnson BD, Nilakantan R, Overbeek E, Reich MF, Shen R, Shi X, Tsou HR, Wang YF, Wissner A: Antitumor activity of HKI-272, an orally active, irreversible inhibitor of the HER-2 tyrosine kinase. Cancer Res. 2004, 64: 3958-3965. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2868.

Burstein H, Awada A, Badwe R, Dirix L, Tan A, Jacod S, Lustgarten S, Vermette J, Zacharchuk C: HKI-272, an irreversible pan erbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor: preliminary phase 2 results in patients with advanced breast cancer [abstract 6061]. Proceedings of the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; 13 to 16. 2007, [http://www.posters2view.com/sabcs07/viewp.php?nu=6061]December ; San Antonio, TX

Normanno N, Campiglio M, De LA, Somenzi G, Maiello M, Ciardiello F, Gianni L, Salomon DS, Menard S: Cooperative inhibitory effect of ZD1839 (Iressa) in combination with trastuzumab (Herceptin) on human breast cancer cell growth. Ann Oncol. 2002, 13: 65-72. 10.1093/annonc/mdf020.

Warburton C, Dragowska WH, Gelmon K, Chia S, Yan H, Masin D, Denyssevych T, Wallis AE, Bally MB: Treatment of HER-2/neu overexpressing breast cancer xenograft models with trastuzumab (Herceptin) and gefitinib (ZD1839): drug combination effects on tumor growth, HER-2/neu and epidermal growth factor receptor expression, and viable hypoxic cell fraction. Clin Cancer Res. 2004, 10: 2512-2524. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0244.

Dickler MN, Cobleigh MA, Miller KD, Klein PM, Winer EP: Efficacy and safety of erlotinib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009, 115: 115-121. 10.1007/s10549-008-0055-9.

Moulder SLONA, Arteaga C, Pins M, Sparano J, Sledge G, Davidson N: Final Results of ECOG1100: A phase I/II study of combined blockade of the ErbB receptor network in patients with HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer (MBC) [abstract 1003]. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25 (suppl): 40s-

Hurwitz HDA, Savage S, Fernando N, Lasalvia S, Whitehead B, Suttle B, Collins D, Ho P, Pandite L: Safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of oral administration of GW786034 in pts with solid tumors [abstract 3012]. J Clin Oncol. 23 (suppl): 19s-

Dejonge MSS, Verweij J, Collins TS, Eskens F, Whitehead B, Suttle AB, Pandite LB, Ho PT, Hurwitz H: A phase I, open-label study of the safety and pharmacokinetics (PK) of pazopanib (P) and lapatinib (L) administered concurrently [abstract 3088]. J Clin Oncol. 24 (suppl): 1016-

Slamon DGH, Kabbinavar FF, Amit O, Richie M, Pandite L, Goodman V: Randomized study of pazopanib + lapatinib vs. lapatinib alone in patients with HER2-positive advanced or metastatic breast cancer [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 26 (suppl): 1016-

Pazopanib Plus Lapatinib Compared To Lapatinib Alone In Subjects With Advanced Or Metastatic Breast Cancer. [http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00347919?term=lapatinib+and+pazopanib&rank=2]

Franklin MC, Carey KD, Vajdos FF, Leahy DJ, de Vos AM, Sliwkowski MX: Insights into ErbB signaling from the structure of the ErbB2-pertuzumab complex. Cancer Cell. 2004, 5: 317-328. 10.1016/S1535-6108(04)00083-2.

Agus DB, Akita RW, Fox WD, Lewis GD, Higgins B, Pisacane PI, Lofgren JA, Tindell C, Evans DP, Maiese K, Scher HI, Sliwkowski MX: Targeting ligand-activated ErbB2 signaling inhibits breast and prostate tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2002, 2: 127-137. 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00097-1.

Fendly BM, Winget M, Hudziak RM, Lipari MT, Napier MA, Ullrich A: Characterization of murine monoclonal antibodies reactive to either the human epidermal growth factor receptor or HER2/neu gene product. Cancer Res. 1990, 50: 1550-1558.

Cho HS, Mason K, Ramyar KX, Stanley AM, Gabelli SB, Denney DW, Leahy DJ: Structure of the extracellular region of HER2 alone and in complex with the Herceptin Fab. Nature. 2003, 421: 756-760. 10.1038/nature01392.

Nahta R, Hung MC, Esteva FJ: The HER-2-targeting antibodies trastuzumab and pertuzumab synergistically inhibit the survival of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004, 64: 2343-2346. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3856.

Agus DB, Gordon MS, Taylor C, Natale RB, Karlan B, Mendelson DS, Press MF, Allison DE, Sliwkowski MX, Lieberman G, Kelsey SM, Fyfe G: Phase I clinical study of pertuzumab, a novel HER dimerization inhibitor, in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 2534-2543. 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.184.

Gelmon KA, Fumoleau P, Verma S, Wardley AM, Conte PF, Miles D, Gianni L, McNally VA, Ross G, Baselga J: Results of a phase II trial of trastuzumab (H) and pertuzumab (P) in patients (pts) with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (MBC) who had progressed during trastuzumab therapy [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26: 1026-

Fumoleau PWA, Miles D, Verma S, Gelmon K, Cameron D, Gianni L, Conte PF, Ross G, McNally V, Baselga J: Safety of pertuzumab plus trastuzumab in a phase II trial of patients with HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer which had progressed during trastuzumab therapy [abstract 73]. Proceedings of the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; 13 to 16. 2007,[http://www.posters2view.com/sabcs07/view.php?nu=SABCS07L_1151]December ; San Antonio, TX

Pegram M: Can we circumvent resistance to ErbB2-targeted agents by targeting novel pathways?. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008, 8 (suppl 3): S121-S130. 10.3816/CBC.2008.s.008.

A Study of Avastin (Bevacizumab) in Combination With Herceptin (Trastuzumab)/Docetaxel in Patients With HER2 Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. [http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00391092?term=nct00391092&rank=1]

Lu CH, Wyszomierski SL, Tseng LM, Sun MH, Lan KH, Neal CL, Mills GB, Hortobagyi GN, Esteva FJ, Yu D: Preclinical testing of clinically applicable strategies for overcoming trastuzumab resistance caused by PTEN deficiency. Clin Cancer Res. 2007, 13: 5883-5888. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2837.

Holden SN, Beeram M, Krop IE, Burris HA, Birkner M, Girish S, Tibbitts J, Lutzker SG, Modi S: A phase I study of weekly dosing of trastuzumab-DM1 in patients with advanced HER2+ breast cancer [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 26 (suppl): 1029-

Burris HA: A phase II study of trastuzumab-DM1 (T-DM1), a HER2 antibody drug-conjugate (ADC), in patients (pts) with HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (MBC). American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Symposium. 2008, Abstract 155.

Neckers L, Schulte TW, Mimnaugh E: Geldanamycin as a potential anti-cancer agent: its molecular target and biochemical activity. Invest New Drugs. 1999, 17: 361-373. 10.1023/A:1006382320697.

Schulte TW, Neckers LM: The benzoquinone ansamycin 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin binds to HSP90 and shares important biologic activities with geldanamycin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998, 42: 273-279. 10.1007/s002800050817.

Zsebik B, Citri A, Isola J, Yarden Y, Szollosi J, Vereb G: Hsp90 inhibitor 17-AAG reduces ErbB2 levels and inhibits proliferation of the trastuzumab resistant breast tumor cell line JIMT-1. Immunol Lett. 2006, 104: 146-155. 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.11.018.

Modi S, Stopeck AT, Gordon MS, Mendelson D, Solit DB, Bagatell R, Ma W, Wheler J, Rosen N, Norton L, Cropp GF, Johnson RG, Hannah AL, Hudis CA: Combination of trastuzumab and tanespimycin (17-AAG, KOS-953) is safe and active in trastuzumab-refractory HER-2 overexpressing breast cancer: a phase I dose-escalation study. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25: 5410-5417. 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.7960.

Norum J, Risberg T, Olsen JA: A monoclonal antibody against HER-2 (trastuzumab) for metastatic breast cancer: a model-based cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Oncol. 2005, 16: 909-914. 10.1093/annonc/mdi188.

Bonneterre ME, Bonneterre J: Reply to the article 'A monoclonal antibody against HER-2 (trastuzumab) for metastatic breast cancer: a model based cost-effectiveness analysis', by J. Norum et al. (Ann Oncol 2005; 16: 909–914). Ann Oncol. 2006, 17: 875-10.1093/annonc/mdj074. reply 875–876

Poncet B, Bachelot T, Colin C, Ganne C, Jaisson-Hot I, Orfeuvre H, Peaud PY, Jacquin JP, Salles B, Tigaud JD, Mechin-Cretinon I, Marechal F, Fournel C, Trillet-Lenoir V: Use of the monoclonal antibody anti-HER2 trastuzumab in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008, 31: 363-368. 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181637356.

El Saghir NS, Eniu A, Carlson RW, Aziz Z, Vorobiof D, Hortobagyi GN: Locally advanced breast cancer: treatment guideline implementation with particular attention to low- and middle-income countries. Cancer. 2008, 113: 2315-2324.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

FJE has served as a consultant for Genentech, GSK and Novartis. FJE has been the principal investigator on a clinical trial funded by GSK, and another clinical trial funded by Novartis. Research funding for the trials was administered by The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. PKHM and FZ have no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morrow, P.K.H., Zambrana, F. & Esteva, F.J. Recent advances in systemic therapy: Advances in systemic therapy for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 11, 207 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr2324

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr2324