Abstract

Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) was initially identified and confirmed primarily by pathology, but is soon to be incorporated into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual criteria as a clinical disease entity. Despite these advances over more than 20 years, current data suggest that the sensitivity of accurate clinical diagnosis of DLB is still very low, although there is mounting evidence that supportive features may increase diagnostic accuracy. Although DLB remains easy to identify pathologically with different cellular pathologies differentiating it from other dementia syndromes, pathological identification using only Lewy body pathology has been shown to be inaccurate due to overlap with patients without dementia symptoms. A number of studies now suggest that a combination of cellular pathologies, which include α-synuclein and β-amyloid deposition as well as dopamine denervation, assist with differentiating this dementia syndrome from others. The clinical and pathological overlap with the tauopathy of Alzheimer’s disease still remains to be clarified. To determine more robust and independent clinicopathological correlates from Alzheimer’s disease, longitudinal prospective studies, using specific clinical batteries on dementia patients reaching the proposed criteria for DLB, with post-mortem assessment of the multiple pathologies associated with dementia, are required. Identifying genetic causes for DLB is another approach to investigate the pathogenesis of DLB. However this approach has been hindered to date by difficulties with identifying DLB clinically. The use of novel techniques is likely to advance knowledge on the pathogenesis of DLB and assist with redefining clinical and pathologic diagnostic criteria. To achieve the goal of more accurate clinical diagnosis of DLB, breakthroughs are necessary on the pathogenesis of DLB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

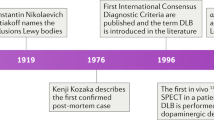

The Lewy body was named after Frederick Lewy who first described the abnormal intracytoplasm inclusions in 1912 in a patient with what is now called Parkinson’s disease (PD). In 1961, Okazaki first described a relationship between the presence of cortical Lewy bodies and dementia[1]. In 1984, Kosaka, Yoshimura, Ikeda and Budka reviewed the existing literature and proposed that these cases should be regarded as a new disease entity, which they termed ‘diffuse Lewy body disease’[2]. Soon after the disease was confirmed by others[3, 4]. The terminology of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) was proposed by scientists attending the 1996 proceedings of the First International Workshop of the Consortium on DLB[5]. Before 1996 when the term DLB was designated, there were several terms to describe the appearance of Lewy bodies in dementia, such as diffuse Lewy body disease, Lewy-body dementia, senile dementia of the Lewy body type, and dementia associated with cortical Lewy bodies[6]. As DLB cases have been included in other dementia subtypes (particularly Alzheimer’s disease or AD) in the past, its importance can only be assessed if the diagnostic criteria allow clear separation of the disorder from these other types of dementia. DLB is now considered part of a spectrum of Lewy body diseases, ie. PD, PD with dementia (PDD) and DLB[7, 8], and is known to often coexist with AD (could be considered as a mixed dementia). To emphasize its clinical features, Japanese scientists proposed that DLB be called “Kosaka’s disease”[9], but this term is yet to be internationally accepted. In fact, DLB is not currently recognized as a diagnosis for dementia in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) for Mental Disorders published by the American Psychiatric Association, although there are plans for its incorporation into the 5th version to be published in 2013.

The clinical criteria for possible and probable DLB diagnosis were last revised in 2005 following the 3rd DLB International Workshop (Table1)[8]. While the central feature of progressive cognitive decline that interferes with daily functioning is essential for diagnosis, the temporal sequence for diagnosis allows this feature to occur with progression in the context of a parkinsonian syndrome where it may only become prominent or persistent after the first few years. An arbitrary ‘one-year rule’ introduced at the same time as the disease entity in 1996 has been continued to be recommended to be applied to distinguish DLB from PDD: If dementia occurs within 12 months of the motor features, the patient should be classified as having a primary diagnosis of DLB[8], although the ‘one-year rule’ is not without challenge[7]. Additional core features required for diagnosis include fluctuating cognition with pronounced variations in attention and alertness, recurrent visual hallucinations that are well formed and detailed, and/or spontaneous features of parkinsonism. Possible DLB is identified if one of these features is present, while probable DLB is identified if two of these features are present. Three suggestive features were included in 2005 to assist with a diagnosis of DLB; rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder, severe narcoleptic sensitivity and low dopamine transporter uptake in basal ganglia demonstrated by SPECT or PET. If one or more suggestive feature is present in addition to one core feature, then probable DLB can be diagnosed. If one or more suggestive feature is present in the absence of any core feature, then possible DLB can be diagnosed. The diagnosis of DLB is less likely 1) in the presence of cerebrovascular disease evident as focal neurologic signs or on brain imaging, 2) in the presence of any physical illness or brain disorder sufficient to account in part or in total for the clinical picture, and 3) if parkinsonism only appears for the first time at a severe stage of dementia. This last criterion appears to be the cause of much over-diagnosis of DLB in current clinical practice (see below).

The accuracy of the diagnostic criteria for DLB is variable depending on the populations assessed, with relatively low clinical sensitivity (lowest 12%, although 88% in recent work) but higher specificity (79-100%)[10–16]. There appears to be an increase in sensitivity with the inclusion of new supportive features discussed above[13, 16]. In the six studies assessing the accuracy of clinical diagnoses since the 2005 criteria, one report selected cases where all clinical symptoms were assessed but determined the accuracy of diagnosis only in those 53 cases with a clinical diagnosis of DLB[12]. A second study of DLB patients assessed whether neuroimaging was of assistance in 20 cases who came to autopsy, finding that dopamine ligand imaging improved diagnosis significantly (88% sensitivity, 100% specificity in this small sample)[13]. A third study also assessed patients with Lewy bodies only and determined which pathology correlated most with the clinical phenotype, asserting that the severity of neurofibrillary tangles relate more to the diagnostic DLB criteria than Lewy bodies[10], consistent with previous suggestions[11]. This was confirmed in a fourth study assessing 304 people 85 years old and above[14]. A much larger series did not use the new supportive clinical features, but assessed clinical versus pathological diagnoses in 2,861 cases in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center registry[15]. The accuracy of diagnosing clinical AD was higher (85% sensitivity, 51% specificity) than that for clinical DLB (32% sensitivity for pure and 12% for mixed, 95% specificity). However, the most recent study assessing 234 consecutive patients with dementia coming to autopsy has shown that including REM sleep behavior disorder significantly improves the diagnostic accuracy of clinical DLB[16]. The still significant clinical under-detection of probable DLB is discussed in this review. In addition, we review the neuropathology of DLB and its overlapping pathology with other disorders, as well as the genetics and pathogenesis of DLB. We expect that as cellular and molecular knowledge on DLB advances, the diagnostic criteria for DLB will undergo further modifications.

Clinical presentation and differentiation of DLB

As stated above, significant cognitive decline is mandatory for the diagnosis of DLB. Patients with DLB usually have deficits on tests of attention, executive function (e.g. planning, prioritizing, and sequencing) and visuospatial ability. In a cross-sectional clinical study[17], memory impairment (57%) was the most common presenting symptom in DLB, followed by visual hallucinations (44%), depression (34%), problem solving difficulties (33%), gait problems (28%), and tremor/stiffness (25%). In contrast, 99% of AD carers reported impaired memory as a presenting symptom, whereas visual hallucinations were a presenting symptom in 3% of the AD cases[17]. These observations support previous suggestions that DLB should be suspected in mild memory impairment cases with visual hallucinations[18], although this feature is not highly prevalent in patients with autopsy confirmed DLB[17]. In community studies[6, 19], DLB accounts for approximately 0.7% of the general population older than 65 years of age, and 5% (3.3% probable, 1.7% possible) of people over 85 years of age. Hospital-based autopsy series report 10-15% of patients with DLB and population-based autopsy series show Lewy body pathology evenly distributed between demented and non-demented individuals, suggesting a substantial pool of preclinical cases[6]. This has been confirmed in more recent, expansive autopsy series[20]. The early identification of DLB, as well as the differentiation of DLB from other conditions, has become very important to determine treatment options, help with behavioral management of patients, and provide informative resources for caregivers.

Fluctuating cognition

Fluctuations may reflect periods of unresponsiveness while awake (e.g., blanking out, zoning out), episodes of excessive somnolence despite adequate night-time sleep, or periods of daytime behavioural confusion with limited awareness of surroundings alternating with normal or near normal function. Cognitive fluctuations have also been described as variability in the patients’ cognitive or functional abilities and periods when the patient regains their ability to perform tasks that they were previously unable to perform. However, studies show that fluctuations in cognition are problematic to define and it is hard to obtain consistent assessments for their presence[11, 21], which has been proposed as the main factor for low sensitivity of the current clinical diagnosis criteria[22]. To overcome this difficulty, there are several clinical tests available for the evaluation of fluctuations: Clinician Assessment of Fluctuation scale, semi-structured One Day Fluctuation Assessment scale, and The Mayo Fluctuations Composite Scale[11, 23]. However, these tools have yet to be evaluated for their reliability and validity[24]. As the prevalence of this feature is high in autopsy confirmed cases of DLB, clear and reliable assessment of fluctuating cognition is warranted.

Recurrent visual hallucination

In DLB, visual hallucinations are typically recurrent and well formed, consisting of three dimensional subjects, people, children or animals. Visual misperceptions (illusions) are also common[6, 19, 25]. Examples of object misperceptions in DLB include mistaking a hinge for a caterpillar, or patterns on a rug for snakes, etc. Auditory hallucinations and delusional ideation can occur in a subgroup of those with visual hallucinations[26]. The most frequent delusional ideas include strangers or intruders in the home or the belief that deceased friends or family members are visiting, and examples of elementary auditory hallucinations include banging, knocking, sizzling, a doorbell or footsteps. These are associated with Lewy body counts in the anterior and inferior temporal lobe, claustrum and the amygdala, regions previously associated with complex visual image generation[27–30]. The presence of visual hallucinations and global cognitive impairment are also associated with deficits in choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) in DLB. ChAT is an indicator of neocortical cholinergic activity, which is more depleted in DLB than in AD[31]. It is unknown whether lower levels of ChAT correlate with greater Lewy body loads in DLB. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) can be used in the clinic to screen visual hallucinations and assess their severity and frequency[32].

Spontaneous parkinsonism

The extrapyramidal signs should be spontaneous or occur subsequent to dementia in DLB[7], although dementia is allowed to occur within one year of earlier parkinsonism according to the current temporal designation of DLB[8], as discussed above. Postural instability, gait difficulty, and facial immobility are axial features common in DLB, while rest tremor of the limbs is less common. Levodopa responsiveness in DLB is also less common[33, 34]. The severity of motor features in DLB can be assessed using the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)[8].

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder

REM sleep behavior disorder can develop in otherwise neurologically-normal adults as well as in those with a neurodegenerative disease[35]. REM sleep behavior disorder has been included as a supportive clinical feature for DLB and has been shown to enhance the diagnosis of DLB[16], possibly because it is a significant risk factor for both cognitive deficits and PD[36]. DLB patients with probable REM sleep behavior disorder have an earlier onset of other symptoms (parkinsonism and visual hallucinations), a more rapid disease course and less AD but similar Lewy-related pathologies compared with DLB patients who do not have REM sleep behaviour disorder[37]. These observations suggest that REM sleep behavior disorder in patients with DLB may indicate a particular subtype of DLB.

Severe neuroleptic sensitivity

About 30 to 50% of DLB patients who take antipsychotic drugs (olanzapine – 58%, clozapine – 11%, thioridazine – 6%) will develop severe neuroleptic sensitivity, manifested as a sudden onset of drowsiness, increased confusion, immobility, and muscle rigidity[38, 39]. Severe neuroleptic sensitivity is not seen in patients with AD, but occurs in 27% of patients with PD, 39% with PDD, and is most frequent in patients with DLB (53%)[38]. It has been proposed that this change in sensitivity is due to dysfunction of dopamine D2 receptors[38]. As severe neuroleptic sensitivity reactions can be fatal, more research and education on this issue needs to be conducted[39].

Low dopamine transporter uptake in basal ganglia demonstrated by SPECT or PET

Low dopamine transporter uptake in the basal ganglia, measured with (123)I-FP-CIT (DaTSCAN) SPECT imaging or (18) fluorodopa PET, is clinically useful in distinguishing DLB from AD[40, 41]. A retrospective study showed that DaTSCAN findings were concordant with the outcome clinical DLB diagnosis in 95% cases[42]. A systematic meta-analysis of published studies on DLB diagnostic accuracy of presynaptic dopaminergic imaging with DaTSCAN revealed 86.5% sensitivity and 93.6% specificity differentiating DLB from non-DLB[43].

Other imaging characteristics

Other supportive features include abnormal cardiac sympathetic imaging using Iodine-123 Metaiodobenzilguanidine (I-123 MIBG), occipital and posterior parietotemporal lobe hypometabolism[44], and relative preservation of medial temporal lobe structures[45], etc. (Table1).

Differentiation

AD and PDD are the two major disorders required to be clinically differentiated from DLB. The most difficult syndrome to differentiate from DLB is AD, as prominent or persistent memory impairment occurs in the early stages of both disorders. In addition, DLB patients with concomitant AD are less likely to have hallucinations compared to patients with pure DLB, possibly because the clinical DLB features are masked by the clinical features of AD[11]. A further difficulty has been that the characteristic features of DLB can often manifest in AD patients when the dementia has progressed to a severe stage, and thus the majority of patients diagnosed with DLB have had severe AD rather than DLB or mixed DLB and AD pathologically[15]. These data show that the core clinical features of DLB are only effective for clinical differentiation from AD at the onset of disease[46]. This problem with the overlap with pathologically proven AD may be assisted with the inclusion of some of the supportive features for DLB[16], but this needs to be evaluated further. A recent study suggests that the assessment of non-motor symptoms associated with PD (olfactory dysfunction, constipation, increased saliva and signs of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder) at the onset of dementia can assist with differentiating DLB from AD[47]. Such non-motor symptoms are being actively studied in large clinical cohorts as prodromes for PD[48] with research on potential prodromal features for DLB also currently underway[49]. Such research may provide important yet-to-be-defined differentiating features.

Differentiating PDD from DLB is currently an arbitrary construct, but at least has proven less problematic. PDD in the context of well-established PD when subsequent dementia becomes evident is easily differentiable from the dominant dementia syndrome observed in most cases of DLB. The clinical diagnostic criteria for PDD have been published and operationalised and use the three core features of DLB[50, 51]. While the clinical diagnostic criteria for "probable" and "possible" PDD has been proposed with a simple, pragmatic set of tests involved[50], the sensitivity (47%) of these tests for diagnosing dementia in the context of PD is low[52]. While the differential diagnosis between DLB and PDD is not problematic due to the artificial construct, the identification of all dementia cases in patients with PD needs to be improved.

Pathological manifestations and differentiation of DLB

The diagnosis of DLB is based on assessing the probability that the pattern and degree of Lewy-related pathology (LRP) versus AD pathology is related to a cognitive disorder[19, 53]. Currently, pure DLB is diagnosed pathologically according to the severity and distribution of LRP in certain brain regions, and Braak neurofibrillary stages less than stage IV[54, 55]. Fibrillar forms of α-synuclein are the major component of LRP (Figure1)[56]. At end stage, α-synuclein LRP is diffusely distributed in cortical and subcortical regions in both DLB and PDD[6, 57]. α-Synuclein-immunoreactive astrocytes are also noted in PDD as well as in DLB (Figure1)[58]. However, novel techniques including paraffin-embedded tissue blotting and protein aggregate filtration assays reveal substantial accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates in presynapses in DLB[59], suggesting that presynaptic α-synuclein aggregates, rather LRP, cause neurodegeneration. Whether such techniques would assist with differential diagnosis needs further examination.

Lewy-related pathologies (LRP) and Aβ deposition in DLB. (A-C) Histofluorecence identification of α-synuclein-positive (A, green) Lewy bodies using thioflavin S (B, blue) for filament localization (C, merge) showing difficulty with immunostaining the mature core filaments of midbrain Lewy bodies. (D) Eosinophilic Lewy body in a pigmented midbrain dopaminergic neuron, (E) mature α-synuclein-positive Lewy body in the neocortex identified using peroxidase immunohistochemistry, (F) immature α-synuclein-positive Lewy body and related star-shaped α-synuclein-positive astrocytes in the neocortex identified using peroxidase immunohistochemistry. (G) α-synuclein-positive Lewy neurites in the hippocampal CA2 region identified using peroxidase immunohistochemistry, and (H) Aβ-positive cortical plaques identified using peroxidase immunohistochemistry. The scale in F and G is equal to that in E.

At present there is a lot of controversy over the clinical significance of LRP and so further refinement of techniques in this area may be warranted. Patients with pathologically-confirmed DLB are not all demented; 40-80% of those have visual hallucinations, 50-80% develop parkinsonism, and overall about 30-50% of subjects demonstrate both visual hallucination and parkinsonism in retrospective studies[11, 50]. In one pathological sample, patients satisfying the McKeith criteria for diffuse neocortical DLB with only mild concomitant AD pathology were demented only 48% of the time with only 54% displaying extrapyramidal symptoms[20]. However, these clinical findings were gathered retrospectively questioning whether the clinical assessment of these patients was sufficiently detailed to discount the presence of other DLB features prior to autopsy. On the other hand, widespread LRP occurs in many sporadic AD cases without parkinsonian symptoms[60], sometimes reaching pathological criteria for both DLB and AD[61]. In particular, familial DLB cases often show concomitant DLB and AD[61]. Retrospective studies show that DLB + AD patients have longer disease durations compared to patients with pure DLB pathology[11]. Further population-based, longitudinal prospective clinical and pathological correlation studies are warranted to determine the clinical significance of LRP in both the normal and dementia populations.

In comparison to LRP, β-amyloid plaques are often seen in DLB compared to PDD[62–65]. Unlike AD, β-amyloid plaques in pure DLB are diffuse and without tau neuritic involvement[17]. Whether or not β-amyloid deposition contributes to any DLB clinical feature particularly, or more to the timing and/or severity of cognitive decline, remains to be determined. The common occurrence of β-amyloid deposition in the setting of clinical DLB may prove more difficult in terms of differentiation from AD, although as discussed above, the assessment of imaging for dopamine transporters seems to assist with the differential diagnosis from AD[66]. This highlights another important pathological aspect to assist with case differentiation, the pattern of cell loss or atrophy. On this aspect, not only can imaging dopamine cell loss assist, but there is also more limited cortical and hippocampal atrophy in DLB versus AD[44]. There is even more limited cell death in PDD, with hippocampal sparing in comparison to DLB[28, 67]. The overlap between these disorders can best be seen as a pathological continuum with dopamine cell loss and widespread LRP observed in both PDD and DLB, with additional β-amyloid deposition and mild cortical and hippocampal atrophy observed in pure DLB, and with greater hippocampal and cortical degeneration associated with additional tau deposition observed in mixed DLB with AD, while AD has the β-amyloid and tau deposition without the widespread LRP. This also highlights the necessity to assess more than one pathological feature in diagnosing these complex syndromes.

Genetics of DLB

By analysing the incidence of familial and sporadic DLB cases in autopsy-confirmed series, a family history of dementia is more common in DLB compared with controls[68] and can run in families in an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern[69]. These studies indicate a genetic contribution to this disorder. Variants in all 3 members of the synuclein gene family, α-, β-, and γ-synuclein affect the risk of developing DLB[70].

γ-Synuclein, aberrantly expressed in many different malignant tumours, is primarily found in the peripheral nervous system and also detected in brain. β-Synuclein, the non-amyloidogenic homolog of α-synuclein, is associated with DLB and not PD. V70M and P123H mutations in the β-synuclein gene have been shown to predispose to DLB[71]. In contrast, genetic mutations in the α-synuclein gene are most commonly associated with PD, with or without dementia. However, an E46K mutation in the α-synuclein gene has been found in one Spanish family with DLB[72] and triplication of the α-synuclein gene occurs in a Swedish American family with early-onset parkinsonism and dementia[73], consistent with current DLB diagnostic criteria. However, mutations in the α-synuclein gene are very rare in familial patients with either PD or DLB[74, 75]. Common genetic factors for the susceptibility of these LRP disorders have been identified in the glucocerebrosidase (GBA) gene[76]. A significantly higher heterozygote frequency for two common GBA gene mutations (N370S and L444P) occurs in patients with PD (2.9%; P <.001) or DLB (3.5%; P = .045) compared with control subjects (0.4%)[77].

A novel locus for DLB has been identified in Belgian families[78]. A genome-wide scan and subsequent fine mapping of candidate loci revealed the locus linkage to 2q35-q36 adjacent to the previously reported PARK11 locus. Screening five candidate genes has not identified the disease-causing mutation[78]. Further analysis of AD and PD causative genes in patients with DLB has been performed showing copy number variants in APP, SNCA and PARK2 genes[76]. However, as the clinical diagnosis of DLB remains difficult, whether current genes associated with either AD or PD pathology influence all aspects of DLB or more particularly some overlapping pathology, remains to be determined. Due to poor sensitivity of the clinical diagnosis of DLB, identification of genes causing DLB requires autopsy-confirmation, rendering such studies difficult. Genetic analysis on further families with multiple autopsies is currently the only way for breakthroughs in the genetics of DLB.

Conclusions

There is a need for better clinical differentiation of people who have a distinct pathological process from PD or AD – that is LRP with β-amyloid deposition but not overt AD tau pathology. There is also a need to determine the clinical consequences of LRP deposition alone without overt parkinsonism or dementia, and the risk factors for this prodrome. Better definitions and more sensitive diagnostic procedures are vital for accurate estimation of prevalence and incidence of DLB across different populations. Finally, identifying causative genes in a better defined population of DLB cases is likely to provide a promising way forward to shed light on any potential different pathogenic mechanism/s for DLB, and assist with increasing the accuracy of clinical diagnosis for this overlapping dementia syndrome.

Authors’ information

YH trained as a neurologist in China with nine years of clinical practice experience and ten years of medical research in Australia. YH currently works as a senior research officer at Neuroscience Research Australia & is a conjoint senior lecturer at the University of New South Wales, Australia.

GMH is an expert in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. She received her degrees from the University of New South Wales and postdoctoral training at the Centre for Neuroscience, Flinders University of South Australia prior to returning to Sydney as an Australian Research Council Queen Elizabeth II Fellow. She has been a research fellow of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia since then and one of the senior scientists at Neuroscience Research Australia (joined in 1993). She has published over 300 research articles and two books, the most recent on Parkinson’s disease, and was president of the Australian Neuroscience Society from 2006–2007. Her pathological work on dementia with Lewy bodies has been incorporated into highly cited research criteria for the diagnosis of this disorder, highlighting the association between Lewy body deposition and visual hallucinations rather than a loss of function.

Abbreviations

- (123)I-FP-CIT:

-

(123)I-2beta-carbometoxy-3beta-(4-iodophenyl)-N-(3-fluoropropyl) nortropane

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- DLB:

-

Dementia with Lewy Bodies

- DSM:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

- I-123 MIBG:

-

Iodine-123 Metaiodobenzilguanidine

- LRP:

-

Lewy-related pathology

- PD:

-

Parkinson’s disease

- PDD:

-

Parkinson’s disease with dementia.

References

Okazaki H, Lipkin LE, Aronson SM: Diffuse intracytoplasmic ganglionic inclusions (Lewy type) associated with progressive dementia and quadriparesis in flexion. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1961, 20: 237-244. 10.1097/00005072-196104000-00007

Kosaka K, Yoshimura M, Ikeda K, Budka H: Diffuse type of Lewy body disease: progressive dementia with abundant cortical Lewy bodies and senile changes of varying degree–a new disease? Clin Neuropathol 1984, 3: 185-192.

Dickson DW, Davies P, Mayeux R, Crystal H, Horoupian DS, Thompson A, Goldman JE: Diffuse Lewy body disease. Neuropathological and biochemical studies of six patients. Acta Neuropathol 1987, 75: 8-15. 10.1007/BF00686786

Hansen L, Salmon D, Galasko D, Masliah E, Katzman R, DeTeresa R, Thal L, Pay MM, Hofstetter R, Klauber M, et al.: The Lewy body variant of Alzheimer's disease: a clinical and pathologic entity. Neurology 1990, 40: 1-8.

McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, Perry EK, Dickson DW, Hansen LA, Salmon DP, Lowe J, Mirra SS, Byrne EJ, et al.: Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology 1996, 47: 1113-1124. 10.1212/WNL.47.5.1113

McKeith I, Mintzer J, Aarsland D, Burn D, Chiu H, Cohen-Mansfield J, Dickson D, Dubois B, Duda JE, Feldman H, et al.: Dementia with Lewy bodies. Lancet Neurol 2004, 3: 19-28. 10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00619-7

McKeith I: Dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease with dementia: where two worlds collide. Pract Neurol 2007, 7: 374-382. 10.1136/jnnp.2007.134163

McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H, Cummings J, Duda JE, Lippa C, Perry EK, et al.: Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2005, 65: 1863-1872. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1

Kosaka K: Kosaka's disease. Shinkei kenkyu no shinpo 2008, 60: 13-16.

Weisman D, Cho M, Taylor C, Adame A, Thal LJ, Hansen LA: In dementia with Lewy bodies, Braak stage determines phenotype, not Lewy body distribution. Neurology 2007, 69: 356-359. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266626.64913.0f

Merdes AR, Hansen LA, Jeste DV, Galasko D, Hofstetter CR, Ho GJ, Thal LJ, Corey-Bloom J: Influence of Alzheimer pathology on clinical diagnostic accuracy in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 2003, 60: 1586-1590. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000065889.42856.F2

Fujishiro H, Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, Smith GE, Graff-Radford NR, Uitti RJ, Wszolek ZK, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW: Validation of the neuropathologic criteria of the third consortium for dementia with Lewy bodies for prospectively diagnosed cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2008, 67: 649-656. 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31817d7a1d

Walker Z, Jaros E, Walker RW, Lee L, Costa DC, Livingston G, Ince PG, Perry R, McKeith I, Katona CL: Dementia with Lewy bodies: a comparison of clinical diagnosis, FP-CIT single photon emission computed tomography imaging and autopsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007, 78: 1176-1181. 10.1136/jnnp.2006.110122

Oinas M, Polvikoski T, Sulkava R, Myllykangas L, Juva K, Notkola IL, Rastas S, Niinisto L, Kalimo H, Paetau A: Neuropathologic findings of dementia with lewy bodies (DLB) in a population-based Vantaa 85+ study. J Alzheim Dis 2009, 18: 677-689.

Nelson PT, Jicha GA, Kryscio RJ, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Cooper G, Xu LO, Smith CD, Markesbery WR: Low sensitivity in clinical diagnoses of dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol 2010, 257: 359-366. 10.1007/s00415-009-5324-y

Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, Smith GE, Lin SC, Silber MH, Pedraza O, Wszolek Z, Graff-Radford NR, Uitti R, Van Gerpen J, et al.: Inclusion of RBD improves the diagnostic classification of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 2011, 77: 875-882. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822c9148

Auning E, Rongve A, Fladby T, Booij J, Hortobagyi T, Siepel FJ, Ballard C, Aarsland D: Early and presenting symptoms of dementia with lewy bodies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2011, 32: 202-208. 10.1159/000333072

Tiraboschi P, Salmon DP, Hansen LA, Hofstetter RC, Thal LJ, Corey-Bloom J: What best differentiates Lewy body from Alzheimer's disease in early-stage dementia? Brain 2006, 129: 729-735. 10.1093/brain/awh725

McKeith IG: Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the Consortium on DLB International Workshop. J Alzheim Dis 2006, 9: 417-423.

Parkkinen L, Pirttila T, Alafuzoff I: Applicability of current staging/categorization of alpha-synuclein pathology and their clinical relevance. Acta Neuropathol 2008, 115: 399-407. 10.1007/s00401-008-0346-6

Verghese J, Crystal HA, Dickson DW, Lipton RB: Validity of clinical criteria for the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 1999, 53: 1974-1982. 10.1212/WNL.53.9.1974

McKeith IG: Dementia with Lewy bodies. Br J Psychiatr 2002, 180: 144-147. 10.1192/bjp.180.2.144

Ferman TJ, Smith GE, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Petersen RC, Knopman D, Graff-Radford N, Parisi J, Dickson DW: DLB fluctuations: specific features that reliably differentiate DLB from AD and normal aging. Neurology 2004, 62: 181-187. 10.1212/WNL.62.2.181

Lee DR, Taylor JP, Thomas AJ: Assessment of cognitive fluctuation in dementia: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012, 27: 989-998. 10.1002/gps.2823

Uchiyama M, Nishio Y, Yokoi K, Hirayama K, Imamura T, Shimomura T, Mori E: Pareidolias: complex visual illusions in dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain 2012, 135: 2458-2469. 10.1093/brain/aws126

Bonanni L, Thomas A, Tiraboschi P, Perfetti B, Varanese S, Onofrj M: EEG comparisons in early Alzheimer's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease with dementia patients with a 2-year follow-up. Brain 2008, 131: 690-705. 10.1093/brain/awm322

Harding AJ, Broe GA, Halliday GM: Visual hallucinations in Lewy body disease relate to Lewy bodies in the temporal lobe. Brain 2002, 125: 391-403. 10.1093/brain/awf033

Harding AJ, Lakay B, Halliday GM: Selective hippocampal neuron loss in dementia with Lewy bodies. Ann Neurol 2002, 51: 125-128. 10.1002/ana.10071

Yamamoto R, Iseki E, Murayama N, Minegishi M, Marui W, Togo T, Katsuse O, Kosaka K, Kato M, Iwatsubo T, Arai H: Correlation in Lewy pathology between the claustrum and visual areas in brains of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurosci Lett 2007, 415: 219-224. 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.01.029

Yamamoto R, Iseki E, Murayama N, Minegishi M, Marui W, Togo T, Katsuse O, Kato M, Iwatsubo T, Kosaka K, Arai H: Investigation of Lewy pathology in the visual pathway of brains of dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Sci 2006, 246: 95-101. 10.1016/j.jns.2006.02.016

Tiraboschi P, Hansen LA, Alford M, Sabbagh MN, Schoos B, Masliah E, Thal LJ, Corey-Bloom J: Cholinergic dysfunction in diseases with Lewy bodies. Neurology 2000, 54: 407-411. 10.1212/WNL.54.2.407

Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994, 44: 2308-2314. 10.1212/WNL.44.12.2308

Molloy S, McKeith IG, O'Brien JT, Burn DJ: The role of levodopa in the management of dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005, 76: 1200-1203. 10.1136/jnnp.2004.052332

Lucetti C, Logi C, Del Dotto P, Berti C, Ceravolo R, Baldacci F, Dolciotti C, Gambaccini G, Rossi G, Bonuccelli U: Levodopa response in dementia with lewy bodies: a 1-year follow-up study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2010, 16: 522-526. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.06.004

Boeve BF, Ferman TJ: Neuropsychological characterization of evolving cognitive decline in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder is important, but not easy. Sleep 2011, 34: 561-562.

Boot BP, Boeve BF, Roberts RO, Ferman TJ, Geda YE, Pankratz VS, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, McDade E, Christianson TJ, et al.: Probable rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder increases risk for mild cognitive impairment and Parkinson disease: a population-based study. Ann Neurol 2012, 71: 49-56. 10.1002/ana.22655

Dugger BN, Boeve BF, Murray ME, Parisi JE, Fujishiro H, Dickson DW, Ferman TJ: Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and subtypes in autopsy-confirmed dementia with Lewy bodies. Mov Disord 2012, 27: 72-78. 10.1002/mds.24003

Aarsland D, Perry R, Larsen JP, McKeith IG, O'Brien JT, Perry EK, Burn D, Ballard CG: Neuroleptic sensitivity in Parkinson's disease and parkinsonian dementias. J Clin Psychiatry 2005, 66: 633-637.

Hassan I: Consultation-liaison psychiatry and prevention of severe neuroleptic sensitivity reactions in dementia with Lewy bodies. Australas Psychiatr 2011, 19: 536-537.

McKeith I, O'Brien J, Walker Z, Tatsch K, Booij J, Darcourt J, Padovani A, Giubbini R, Bonuccelli U, Volterrani D, et al.: Sensitivity and specificity of dopamine transporter imaging with 123I-FP-CIT SPECT in dementia with Lewy bodies: a phase III, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol 2007, 6: 305-313. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70057-1

Klein JC, Eggers C, Kalbe E, Weisenbach S, Hohmann C, Vollmar S, Baudrexel S, Diederich NJ, Heiss WD, Hilker R: Neurotransmitter changes in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson disease dementia in vivo. Neurology 2010, 74: 885-892. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d55f61

Kemp PM, Clyde K, Holmes C: Impact of 123I-FP-CIT (DaTSCAN) SPECT on the diagnosis and management of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies: a retrospective study. Nucl Med Commun 2011, 32: 298-302. 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328343d4ec

Papathanasiou ND, Boutsiadis A, Dickson J, Bomanji JB: Diagnostic accuracy of (1)(2)(3)I-FP-CIT (DaTSCAN) in dementia with Lewy bodies: a meta-analysis of published studies. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012, 18: 225-229. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.09.015

Kantarci K, Lowe VJ, Boeve BF, Weigand SD, Senjem ML, Przybelski SA, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Knopman DS, Smith GE, et al.: Multimodality imaging characteristics of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Aging 2012, 33: 2091-2105. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.024

Vemuri P, Simon G, Kantarci K, Whitwell JL, Senjem ML, Przybelski SA, Gunter JL, Josephs KA, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, et al.: Antemortem differential diagnosis of dementia pathology using structural MRI: Differential-STAND. Neuroimage 2011, 55: 522-531. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.073

Boeve BF, Molano JR, Ferman TJ, Smith GE, Lin SC, Bieniek K, Haidar W, Tippmann-Peikert M, Knopman DS, Graff-Radford NR, et al.: Validation of the Mayo Sleep Questionnaire to screen for REM sleep behavior disorder in an aging and dementia cohort. Sleep Med 2011, 12: 445-453. 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.12.009

Chiba Y, Fujishiro H, Iseki E, Ota K, Kasanuki K, Hirayasu Y, Satoa K: Retrospective survey of prodromal symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies: comparison with Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2012, 33: 273-281. 10.1159/000339363

Olanow CW, Obeso JA: The significance of defining preclinical or prodromal Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2012, 27: 666-669. 10.1002/mds.25019

Jicha GA, Schmitt FA, Abner E, Nelson PT, Cooper GE, Smith CD, Markesbery WR: Prodromal clinical manifestations of neuropathologically confirmed Lewy body disease. Neurobiol Aging 2010, 31: 1805-1813. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.017

Dubois B, Burn D, Goetz C, Aarsland D, Brown RG, Broe GA, Dickson D, Duyckaerts C, Cummings J, Gauthier S, et al.: Diagnostic procedures for Parkinson's disease dementia: recommendations from the movement disorder society task force. Mov Disord 2007, 22: 2314-2324. 10.1002/mds.21844

Emre M, Aarsland D, Brown R, Burn DJ, Duyckaerts C, Mizuno Y, Broe GA, Cummings J, Dickson DW, Gauthier S, et al.: Clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2007, 22: 1689-1707. quiz 1837 10.1002/mds.21507

Barton B, Grabli D, Bernard B, Czernecki V, Goldman JG, Stebbins G, Dubois B, Goetz CG: Clinical validation of Movement Disorder Society-recommended diagnostic criteria for Parkinson's disease with dementia. Mov Disord 2012, 27: 248-253. 10.1002/mds.24059

Dickson DW, Braak H, Duda JE, Duyckaerts C, Gasser T, Halliday GM, Hardy J, Leverenz JB, Del Tredici K, Wszolek ZK, Litvan I: Neuropathological assessment of Parkinson's disease: refining the diagnostic criteria. Lancet Neurol 2009, 8: 1150-1157. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70238-8

McKeith IG, Rowan E, Askew K, Naidu A, Allan L, Barnett N, Lett D, Mosimann UP, Burn D, O'Brien JT: More severe functional impairment in dementia with lewy bodies than Alzheimer disease is related to extrapyramidal motor dysfunction. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr 2006, 14: 582-588. 10.1097/01.JGP.0000216177.08010.f4

Dickson DW: Neuropathology of non-Alzheimer degenerative disorders. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2009, 3: 1-23.

Wakabayashi K, Matsumoto K, Takayama K, Yoshimoto M, Takahashi H: NACP, a presynaptic protein, immunoreactivity in Lewy bodies in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett 1997, 239: 45-48. 10.1016/S0304-3940(97)00891-4

Braak H, Ghebremedhin E, Rub U, Bratzke H, Del Tredici K: Stages in the development of Parkinson's disease-related pathology. Cell Tissue Res 2004, 318: 121-134. 10.1007/s00441-004-0956-9

Braak H, Sastre M, Del Tredici K: Development of alpha-synuclein immunoreactive astrocytes in the forebrain parallels stages of intraneuronal pathology in sporadic Parkinson's disease. Acta Neuropathol 2007, 114: 231-241. 10.1007/s00401-007-0244-3

Kramer ML, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ: Presynaptic alpha-synuclein aggregates, not Lewy bodies, cause neurodegeneration in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurosci 2007, 27: 1405-1410. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4564-06.2007

Jellinger KA: Alpha-synuclein pathology in Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease brain: incidence and topographic distribution–a pilot study. Acta Neuropathol 2003, 106: 191-201. 10.1007/s00401-003-0725-y

Walker Z, McKeith I, Rodda J, Qassem T, Tatsch K, Booij J, Darcourt J, O'Brien J: Comparison of cognitive decline between dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2012, 2: e000380. 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000380

Halliday GM, Song YJ, Harding AJ: Striatal beta-amyloid in dementia with Lewy bodies but not Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm 2011, 118: 713-719. 10.1007/s00702-011-0641-6

Gomperts SN, Rentz DM, Moran E, Becker JA, Locascio JJ, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Elmaleh DR, Shoup T, Fischman AJ, et al.: Imaging amyloid deposition in Lewy body diseases. Neurology 2008, 71: 903-910. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326146.60732.d6

Kalaitzakis ME, Walls AJ, Pearce RK, Gentleman SM: Striatal Abeta peptide deposition mirrors dementia and differentiates DLB and PDD from other parkinsonian syndromes. Neurobiol Dis 2011, 41: 377-384. 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.005

Gomperts SN, Locascio JJ, Marquie M, Santarlasci AL, Rentz DM, Maye J, Johnson KA, Growdon JH: Brain amyloid and cognition in Lewy body diseases. Mov Disord 2012, 27: 965-973. 10.1002/mds.25048

Villemagne VL, Okamura N, Pejoska S, Drago J, Mulligan RS, Chetelat G, O'Keefe G, Jones G, Kung HF, Pontecorvo M, et al.: Differential diagnosis in Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies via VMAT2 and amyloid imaging. Neurodegener Dis 2012, 10: 161-165. 10.1159/000334535

Aarsland D, Ballard CG, Halliday G: Are Parkinson's disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies the same entity? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2004, 17: 137-145. 10.1177/0891988704267470

Woodruff BK, Graff-Radford NR, Ferman TJ, Dickson DW, DeLucia MW, Crook JE, Arvanitakis Z, Brassler S, Waters C, Barker W, Duara R: Family history of dementia is a risk factor for Lewy body disease. Neurology 2006, 66: 1949-1950. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219812.20616.b3

Harding AJ, Das A, Kril JJ, Brooks WS, Duffy D, Halliday GM: Identification of families with cortical Lewy body disease. Am J Med Genet B 2004, 128B: 118-122. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30014

Nishioka K, Wider C, Vilarino-Guell C, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Lincoln SJ, Kachergus JM, Jasinska-Myga B, Ross OA, Rajput A, Robinson CA, et al.: Association of alpha-, beta-, and gamma-Synuclein with diffuse lewy body disease. Arch Neurol 2010, 67: 970-975. 10.1001/archneurol.2010.177

Ohtake H, Limprasert P, Fan Y, Onodera O, Kakita A, Takahashi H, Bonner LT, Tsuang DW, Murray IV, Lee VM, et al.: Beta-synuclein gene alterations in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 2004, 63: 805-811. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000139870.14385.3C

Zarranz JJ, Alegre J, Gomez-Esteban JC, Lezcano E, Ros R, Ampuero I, Vidal L, Hoenicka J, Rodriguez O, Atares B, et al.: The new mutation, E46K, of alpha-synuclein causes Parkinson and Lewy body dementia. Ann Neurol 2004, 55: 164-173. 10.1002/ana.10795

Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Peuralinna T, Dutra A, Nussbaum R, et al.: alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson's disease. Science 2003, 302: 841. 10.1126/science.1090278

Higuchi S, Arai H, Matsushita S, Matsui T, Kimpara T, Takeda A, Shirakura K: Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene and sporadic Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and dementia with lewy bodies. Exp Neurol 1998, 153: 164-166. 10.1006/exnr.1998.6868

El-Agnaf OM, Curran MD, Wallace A, Middleton D, Murgatroyd C, Curtis A, Perry R, Jaros E: Mutation screening in exons 3 and 4 of alpha-synuclein in sporadic Parkinson's and sporadic and familial dementia with Lewy bodies cases. Neuroreport 1998, 9: 3925-3927. 10.1097/00001756-199812010-00029

Meeus B, Verstraeten A, Crosiers D, Engelborghs S, Van den Broeck M, Mattheijssens M, Peeters K, Corsmit E, Elinck E, Pickut B, et al.: DLB and PDD: a role for mutations in dementia and Parkinson disease genes? Neurobiol Aging 2012, 33: 629 e5-629 e18.

Mata IF, Samii A, Schneer SH, Roberts JW, Griffith A, Leis BC, Schellenberg GD, Sidransky E, Bird TD, Leverenz JB, et al.: Glucocerebrosidase gene mutations: a risk factor for Lewy body disorders. Arch Neurol 2008, 65: 379-382. 10.1001/archneurol.2007.68

Bogaerts V, Engelborghs S, Kumar-Singh S, Goossens D, Pickut B, van der Zee J, Sleegers K, Peeters K, Martin JJ, Del-Favero J, et al.: A novel locus for dementia with Lewy bodies: a clinically and genetically heterogeneous disorder. Brain 2007, 130: 2277-2291. 10.1093/brain/awm167

Acknowledgements

YH is supported by a Goldstar Award of University of New South Wales. GMH has a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (630434). We’d like to thank Heidi Cartwright for assistance with the figure work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

There are no financial competing interests to declare in relation to this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

YH drafted the manuscript. GMH conceived the structure of the manuscript & revised the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Y., Halliday, G. Can we clinically diagnose dementia with Lewy bodies yet?. Transl Neurodegener 2, 4 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-9158-2-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-9158-2-4