Abstract

Plants, as sessile organisms experience various abiotic stresses, which pose serious threat to crop production. Plants adapt to environmental stress by modulating their growth and development along with the various physiological and biochemical changes. This phenotypic plasticity is driven by the activation of specific genes encoding signal transduction, transcriptional regulation, ion transporters and metabolic pathways. Rice is an important staple food crop of nearly half of the world population and is well known to be a salt sensitive crop. The completion and enhanced annotations of rice genome sequence has provided the opportunity to study functional genomics of rice. Functional genomics aids in understanding the molecular and physiological basis to improve the salinity tolerance for sustainable rice production. Salt tolerant transgenic rice plants have been produced by incorporating various genes into rice. In this review we present the findings and investigations in the field of rice functional genomics that includes supporting genes and networks (ABA dependent and independent), osmoprotectants (proline, glycine betaine, trehalose, myo-inositol, and fructans), signaling molecules (Ca2+, abscisic acid, jasmonic acid, brassinosteroids) and transporters, regulating salt stress response in rice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

World agriculture faces a challenging task to produce 70% more food for an additional 2.3 billion people by 2050 (FAO 2009). The lower agriculture crop productivity is mostly attributed to various abiotic stresses, which is a major area of concern to cope with the increasing food requirements (Shanker and Venkateswarlu 2011). The major abiotic stresses includes high salinity, drought, cold, and heat negatively influence the survival, biomass production and yield of staple food crops which is a major threat to food security worldwide (Thakur et al. 2010; Mantri et al. 2012).

Among abiotic stresses, soil salinity is one of the most brutal environmental factors and a complex phenotypic and physiological phenomenon in plants imposing ion imbalance or disequilibrium, hyperionic and hyperosmotic stress, disrupting the overall metabolic activities and thus limiting the productivity of crop plants worldwide (Munns and Tester 2008). Worldwide more than 80 million hectares of irrigated land (representing 40% of total irrigated land) have already been damaged by salt (Xiong and Zhu 2001). Salt stress leads to severe inhibition of plant growth and development, membrane damages, ion imbalances due to Na+ and Cl- accumulation, enhanced lipid peroxidation and increased production of reactive oxygen species like superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals. Area under salt stress is increasing due to many factors including climate change, rise in sea levels, excessive irrigation without proper drainage in inlands and underlying rocks rich in harmful salts etc. It is estimated that if current scenario of salinity stress would persist, there may be loss of 50% of present cultivated land for agriculture by 2050 (Wang et al. 2003).

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is the world’s most important food crop and a primary source of food for more than half of the population. More than 90 per cent of the world’s rice is grown and consumed in Asia, where 60 percent of the earth’s people live. Salinity is the most common abiotic stress encountered by rice plants and classified as a salt sensitive crop in their early seedling stages (Lutts et al. 1995) and limit its productivity (Todaka et al. 2012). To improve the yield under salt stress condition, it is essential to understand the fundamental molecular mechanisms behind stress tolerance in plants. Salinity stress tolerance is a quantitative trait which is controlled by multiple genes (Chinnusamy et al. 2005). During the last two decades, number of genes conferring salt stress tolerance in plants have been isolated and they are involved in signal transduction and transcription regulation (Chinnusamy et al. 2006; Kumari et al. 2009), ion transporters (Verma et al. 2007; Singh et al. 2008; Uddin et al. 2008) and metabolic pathways (Sakamoto et al. 1998; Singla-Pareek et al. 2008). In the current review we try to focus on the salt responsive genes and genome networks, signal transduction, osmoprotectants and ion transporters involved in salinity stress response in rice.

Review

Salt stress tolerance-supportive genes and pathways in rice

Salt stress evokes both osmotic stress and ionic stress which inhibits the plant’s normal cell growth and division. To encounter the adverse environment, plants maintain osmotic and ion homeostasis with rapid osmotic and ionic signaling (Figure 1). Osmotic stress due to high salt rapidly increases abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis, thus regulating ABA-dependent stress response pathway. There are several salt stress inducible genes which are ABA-independent (Figure 2).

Overall signaling pathway in rice during salt stress. Salt stress evokes both osmotic and ionic stress. Osmotic stress signaling is transduced via ABA-dependent or ABA-independent pathway. ABA dependent pathway includes mitogen activated protein kinase (MAP Kinase) cascades, calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPK), receptor-like kinases (RLK), SNF1-related protein kinases (SnRK), transcription factors (OsRAB1, MYC/MYB and OsNAC/SNAC) and micro RNAs. ABA-independent pathway includes transcription factors (OsDREB1 and OsDREB2) and stress related genes (OsPSY1, OsNCEDs). Ionic stress does signaling via Ca2+/PLC pathway and salt overly sensitive (SOS) pathway and Calmodulin (CaM) pathway. Ca2+ is sensed by Ca2+ sensor (OsCBL4) and the sensor activates calcineurin B-like protein kinase (OsCIPK24), which in turns activates Na+/H+ antiporter (OsSOS1), H+/Ca+ antiporter (OsCAX1), vacuolar H+/ATPase, vacuolar Na+/H+ exchangers (OsNHX1) and suppress K+/Na+ symporter (OsHKT1) to maintain ionic homeostasis under salt stress. Ca2+ also activates calmodulin (OsMSR2) which also activates vacuolar Na+/H+ exchanger (OsNHX1). Blue arrow indicates ABA dependent pathway, green arrow shows ABA-independent pathway, violet arrow shows ROS pathway, red arrow shows Ca2+/PLC pathway and orange arrow shows SOS pathway.

Salt stress tolerance via ABA-dependent pathway

High salinity-induced osmotic stress increases the biosynthesis of ABA. ABA biosynthesis via terpenoid pathway starting from isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) has been reviewed in rice (Ye et al. 2012). Among many genes involved in this pathway, a phytoene synthase gene, OsPSY3 and 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenases genes (OsNCED3, OsNCED4 and OsNCED5) are induced one hour after salt stress and their expression is well correlated to the level of ABA in rice roots (Welsch et al. 2008). ABA then acts as a regulator initiating second round of signaling salt stress response in ABA-dependent pathway. Here we reviewed genes for protein kinases (Receptor-like kinases, RLKs; Mitogen activated protein kinases, MAPKs; SNF1-related protein kinases, SnRKs; Ca2+ dependent protein kinases, CDPKs), transcription factors (TFs), micro RNAs and reactive oxygen species (ROS) involved in the salt stress tolerance through ABA-dependent pathway (Figure 2).

In plant, protein kinases play important roles in regulating the stress signal transduction pathways. Receptor-like kinases (RLKs) have important roles in plant growth, development and stress responses. Salt, drought, H2O2 and ABA treatments induced the expression of a putative RLK gene, OsSIK1. Transgenic rice plants overexpressing OsSIK1 (OsSIK1-ox) show higher tolerance to salt and drought stresses than control plants and the knock-out mutants sik1 as well as RNA interference (RNAi) plants (Ouyang et al. 2010). Mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinase cascades play a crucial role in salt stress response in rice as well. Until now, at least two salt inducible MEKKs have been reported in rice. One of them is OsEDR1 which is upregulated by various environmental stresses such as high salt, physical cutting and hydrogen peroxide (Kim et al. 2003). A putative MEKK mutant, dsm1, showed sensitivity to salt stress as well as drought stress than wild type plants (Ning et al. 2010). Although these genes are responsive to salt stress, there is no evidence that the MEKKs are regulating any downstream MKK. Several salt-inducible MAPKs have been reported in rice. Transcriptional regulation of OsMAPK4 by salt, cold and sugar starvation was reported although its ABA-dependency is not clear (Fu et al. 2002). Biotic and abiotic stress inducible OsMAPK5 has been cloned and overexpressed in rice which subsequently exhibited increased tolerance to salt, drought and cold stresses with increased kinase activity (Xiong et al. 2003). Expression of two novel MAPKs, OsMSRMK2 and OsMSRMK3 were induced by various environmental stresses suggesting their possible involvement in defense/stress response pathways (Agrawal et al. 20022003). A putative salt and ABA-inducible MAPK gene was introduced into transgenic rice and the plants exhibited higher Na+/K+ ratio than OsMAPK44 suppressed plants under salt stress indicating that OsMAPK44 may have a role in ion balance during salt stressed condition (Jeong et al. 2006). Overexpression of a drought stress inducible OsMAPK33 in transgenic rice also revealed a result similar to that of OsMAPK44 showing higher Na+/K+ ratio than wild type plants indicating the negative role of OsMAPK33 in salt stress tolerance through unfavorable ion homeostasis (Lee et al. 2011). Although several salt stress-related MAPKs have been reported, the linkage to upstream MKK or to downstream targets are not clear yet (Singh and Jwa, 2013).

An ABA-dependent Ca2+-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs), OsCPK21, have been cloned and the OsCPK21-ox transgenic rice exhibited higher salt stress tolerance than wild-type plant with enhanced expression of the ABA and salt-stress inducible genes such as OsNAC6 and Rab21 (Asano et al. 2011). An SNF1-related protein kinase (SnRK) functions in salt stress tolerance as well. In rice, ten members of SnRK2 family have been shown to be activated by hyperosmotic stress through phosphorylation (Kobayashi et al. 2004). Among them SAPK4 seems to play a role in the salt stress tolerance. SAPK4-ox transgenic rice revealed an improved salt tolerance with a reduced Na+ accumulation in the cytosol. The vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter gene, OsNHX1 is less expressed in the transgenic plants, indicating the reduced Na+ accumulation due to cellular Na+ exclusion rather than vacuolar sequestration of the ion (Diedhiou et al. 2008).

Transcriptional regulatory network of ABA-dependent TFs (Figure 2) is recently reviewed (Todaka et al., 2012). Promoter regions of ABA-inducible genes have conserved cis-acting element, ABRE, where bZIP-type TFs bind (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki 2006; Todaka et al. 2012). A T-DNA insertion mutant of salt stress inducible bZIP TF, OsABF2, increased sensitivity to salt stresses compared to control plant indicating that OsABF2 is a positive regulator of salt stress (Hossain et al. 2010). OsABF2 binds to ABRE and its N-terminal region transactivated a downstream reporter gene in yeast. Overexpression of ABA-dependent stress inducible OsbZIP23 enhanced tolerance to salt and drought stresses (Xiang et al. 2008). On the other hand, overexpression of salt and ABA responsive OsABI5, another bZIP-type TF gene showed high sensitivity to salt stress, whereas transgenic rice plants expressing antisense OsABI5 showed increased salt stress tolerance. The OsABI5 protein is localized in the nucleus and binds to a G-box element (Zou et al. 2008). These opposing functions displayed by bZIP TFs, are still unclear. Microarray analysis combined with expressed sequence tag analysis of rice 89 OsbZIP genes revealed that no single gene was activated by only salt stress although several genes were activated by drought stress together (Nijhawan et al. 2008). This result may indicate that stress inducible OsbZIPs are mostly related to osmotic stress signaling via ABA.

MYB TFs containing a highly conserved DNA-binding MYB domain of 52 amino acids are also involved in the regulation of salt stress response via ABA-dependent pathway. Overexpression of a stress inducible OsMYB3R-2 improved salt stress tolerance along with cold and drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis, with increased expression of DREB2A, COR15a and RCI2A (Dai et al. 2007). Transgenic rice overexpressing OsMYB2 also showed an enhanced salinity stress tolerance along with drought and cold stress tolerance without compromising the growth rate as compared with control (Yang et al. 2012). In the transgenic rice some putative downstream genes such as OsLEA3, OsRab16A and OsDREB2A were up regulated suggesting that OsMYB2 encodes a stress-responsive MYB TF that may act as a master switch in the stress tolerance.

NAC-type TFs also regulate some salt-responsive genes through ABA-dependent manner. They were isolated initially from Arabidopsis by yeast one hybrid screening as TFs that regulate expression of a salt-inducible ERD1 (Tran et al. 2004). High salinity stress induces several NAC genes in rice as well. Overexpression of salt stress inducible SNAC1 (Hu et al. 2006) and OsNAC6 showed improved tolerance to high salinity stress although growth retardation and low yield were exhibited in OsNAC6-ox under the non-stress condition (Nakashima et al. 2007). Recently, it was shown that OsHDAC1 encoding a histone deacetylase epigenetically represses OsNAC6 expression, so the root growth retardation of OsNAC6 overexpressor is similar to the phenotype of OsHDAC1 knock-out (Chung et al. 2009). OsNAC5, another salt inducible NAC TF, binds to the NAC recognition core sequence (CACG) of OsLEA3 promoter and the transgenic overexpressor of OsNAC5 also showed improved salt tolerance (Takasaki et al. 2010). The OsNAC5 overexpression also correlated positively with accumulation of compatible solutes such as proline and soluble sugars (Song et al. 2011).

Zinc finger TFs were first recognized in Xenopus TFIIIA as a repeated zinc-binding motif containing conserved cysteine and histidine ligands (Miller et al. 1985). From rice, salt stress-responsive OSISAP1-ox conferred tolerance to salt, cold and dehydration stress in transgenic tobacco (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2004). TFIIIA-type ZFP252–ox rice also showed enhanced salt and drought tolerance with the elevated level of stress defense genes, as compared with ZFP252 antisense and non-transgenic plants (Xu et al. 2008). Huang et al. (2009) have isolated DST (drought and salt tolerance) gene, which negatively regulates stomatal closure and directs modulation of genes related to H2O2 homeostasis. DST mutant increases stomatal closure and reduces stomatal density, thus resulting in enhanced salt and drought tolerance in rice. Another salt responsive zinc finger protein gene ZFP179-ox leads to increased salt stress tolerance with increased level of free proline and soluble sugars in transgenic rice (Sun et al. 2010). An increased level of expression of a number of stress-related genes, including OsDREB2A, OsP5CS, OsProT, and OsLEA3 was observed in the transgenic rice. Recently, a salt inducible OsTZF1, a CCCH-type zinc finger protein, has been shown to bind to U-rich regions in the 3' untranslated region of mRNAs (Jan et al. 2013) and overexpression of OsTZF1 showed improved tolerance to salt and drought stresses, OsTZF1 was implicated to play a role in RNA metabolism of stress-responsive genes.

WRKY TFs are also involved in stress response. Overexpression of OsWRKY13 reduced salt stress tolerance via antagonistic inhibition of SNAC1 in rice indicating that OsWRKY13 is a negative regulator of salt stress response (Qiu et al. 2008). Similarly, OsWRKY45-2 suppressing lines showed increased salt stress tolerance with reduced ABA sensitivity (Tao et al. 2011). A salt-inducible AP2/ERF type TF gene, OsERF922–ox rice shows decreased tolerance to salt stress with an increased Na+/K+ ratio in the shoots (Liu et al. 2012). Apart from TFs many other downstream genes are involved in salt tolerance in rice. Hoshida et al. (2000) examined the increased photorespiration effect on the salt tolerance by overexpressing chloroplastic glutamine synthetase (GS2) gene from rice. GS2-ox rice showed increased salt stress tolerance retaining more than 90% activity of photosystem II in comparison to complete loss of photosystem II in control plant. Overexpression of a salt stress inducible JAZ protein gene, OsTIFY11a, resulted in increased salt and dehydration stress tolerance in rice, yet the function of the protein is not clear (Ye et al. 2009). OsSKIPa (Ski-interacting protein) expression is induced by various abiotic stresses and phytohormone treatments. Overexpression of OsSKIPa, also exhibited significantly improved growth performance in the salt and drought resistance with increased transcript levels of many stress-related genes, such as SNAC1 and rice homologs of CBF2, PP2C and RD22 (Hou et al. 2009).

Recently, it has been known that microRNAs (miRNAs) play a key role in the regulation of gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. Under salt-stressed condition, expression of two microRNAs, osa-MIR396c and osa-MIR393, decreased in ABA-dependent manner and overexpression of both miRNAs resulted to a reduced salt stress tolerance, which is lower than the wild-type plants (Gao et al. 20102011). This suggests that these miRNAs are have some role in the salt stress tolerance, although the molecular mechanism is not clear yet.

In barley HVA1 encodes a late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) protein, which is thought as a molecular chaperon. Expression of HVA1 gene led to significantly increased salt and drought tolerance in transgenic rice (Xu et al. 1996). A rice LEA gene, OsLEA3-2, was also overexpressed in rice as well as in yeast. When tested to salt stress, these transgenic organisms showed enhanced growth performance supporting the idea that LEA proteins play important role in the protection of plants under stressed conditions (Duan and Cai 2012). OsLEA3-2 was shown to protect lactate dehydrogenase from aggregation on dessication in vitro.

Salt stress tolerance via ABA-independent pathway

There are several salt stress inducible genes which are ABA-independent. These include genes for DREB1 and DREB2 TFs, some kinases, spingolipid biosynthesis enzymes, and ROS-producing/scavenging enzymes. CBF/DREB-type genes first identified from Arabidopsis encode AP2/ERF domains that bind to a cis-acting element, DRE/CRT with a core sequence A/GCCGAC (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki 2005; Todaka et al. 2012). Rice genome contains at least fourteen DREB-type genes, among which OsDREB1A, OsDREB1F and OsDREB2A are induced by salt stress and their overexpression displayed strong abiotic stress tolerance. Transgenic Arabidopsis or rice overexpressing OsDREB1A, OsDREB1F and OsDREB2A showed improved salinity tolerance (Dubouzet et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2008; Mallikarjuna et al. 2011). Microarray analysis revealed the target stress-inducible genes of OsDREB1A and OsDREB2A encoded proteins thought to function in stress tolerance in the plants, which is similar with the target genes of DREB1 and DREB2 proteins in Arabidopsis (Sakuma et al. 2006 Jeon and Kim 2013). DRE-containing promoter region of OsDhn1 is activated by OsDREB1A and OsDREB1D (Lee et al. 2013). These observations showed that the DREB/CBF TFs are conserved in rice and Arabidopsis and DREB-type genes are useful for improvement of salt stress tolerance in transgenic rice.

ABA-independent kinases are also involved in salt stress tolerance. Overexpression of a CDPK, OsCDPK7 enhanced salt stress tolerance in transgenic rice and the extent of tolerance correlated well with the level of OsCDPK7 expression (Saijo et al. 2000). It was found that knockout plants of OsGSK1, a negative regulator gene of brassinosteroid signaling, showed enhanced tolerance to salt as well as other stresses suggesting that BR plays important role for stress tolerance (Koh et al. 2007). OsCPK12, a member of CDPK family, negatively regulates the expression of OsrbohI while it positively regulates ROS detoxification by controlling the expression of OsAPX 2 and OsAPX 8 under high salinity condition. The accumulation of H2O2 in OsCPK12-ox plants during salt stress was less than that in WT plants, whereas in oscpk12 and OsCPK12 RNAi plants the accumulation was more (Asano et al. 2012). This shows that OsCPK12 confers salt stress tolerance by repressing ROS accumulation rather than by affecting ABA mediated salt stress signaling.

ABA-independent ROS scavenging system is also involved in salt stress tolerance. A salt responsive malic enzyme gene in rice, NADP-ME, was ectopically expressed in Arabidopsis which resulted in enhanced salt stress tolerance probably due to the increased reducing power of ROS (Liu et al. 2007). A mitochondrial superoxide dismutase gene Mn-SOD from Saccharomyces cerevisiae was expressed in rice chloroplast. The transgenic rice plants failed to show salt tolerance but decrease of SOD activities was slower than those of wild type at high salinity condition (Tanaka et al. 1999). Recently, katE encoding catalase from E. coli was transformed into rice which subsequently showed higher salt stress tolerance than the wild type with enhanced level (1.5 to 2.5 fold) of the catalase activity. Alternative oxidase (AOX) is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein that functions as terminal oxidase in the alternative (cyanide resistant) pathway, and AOX serves as oxidation stress reliever from environmental stresses, particularly salt and dehydration stress (Purvis 1997; Cournac et al. 2002). An AOX gene in rice OsIM1 was identified as salt responsive gene by using differential display method indicating the role of AOX pathway under salt stress (Kong et al. 2003). This implicates the importance of ROS scavenging system in the plant salt stress tolerance (Motohashi et al. 2010). Salt stress supportive genes described in this section is reported in supplemental information (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Signaling molecules regulating salt stress in rice

Under salinity stress conditions, diverse signaling molecules such as phospholipids, hormones and calcium ions (Ca2+) regulate stress signaling pathways for maintaining an osmotic adjustment or homeostasis and regulating plant growth and development. Plant hormonal regulations and Ca2+ dependent modification of enzymatic activities are coordinately or independently integrated into the stress signaling pathways. In this section, we reviewed the recent advances in molecular mechanisms of how these signaling molecules are concerted to cytosolic and nuclear events for maintaining ionic homeostasis and salt stress tolerance in plants.

Phospholipids and Ca2+ ions

As signaling molecules, phospholipids including IP3 (Inositol triphosphate) DAG (Diacylglycerol) and PA (phosphatidic acid) seem to play an important structural roles during stress responses in inducing cytosolic Ca2+ spiking. Although the precise roles of phospholipid-based signaling in plants are still underexplored, some recent evidences have revealed their possible involvement in salt stress tolerance (Zhu 2002). Under stress conditions, PA and IP3 levels were rapidly increased in rice, Arabidopsis and tobacco (Zhu 2002; Darwish et al. 2009). Furthermore, several studies have shown that IP3 and its biosynthetic related genes rapidly increased in response to hyperosmotic stress and stress hormone ABA treatment (Drobak and Watkins 2000; DeWald et al. 2001). The formation of the phospholipid-based signaling molecules is mainly regulated by phospholipase C and D (PLC/ PLD). IP3 act as strong elicitors in mobilizing cytosolic Ca2+ levels in plants (Zhu 2002). This implies the activation of phospholipid formations for salt stress-induced cytosolic Ca2+ spiking possibly by membrane anchored salt signaling sensor proteins.

It has been well established that high salt stress rapidly leads to cytosolic Ca2+ spiking. This event spontaneously initiates the stress signaling pathways for stress tolerance via stimulating various Ca2+ binding proteins including CBL-CIPKs, CDPKs and calmodulins (Mahajan et al. 2008; Kader and Lindberg 2010). Direct evidences of the essential role of Ca2+ spiking in salt tolerance are provided by identification of Arabidopsis sos3 (Salt Overlay Sensitive3) mutants which are oversensitive to salt stress (Mahajan et al. 2008). The SOS3 encodes an EF-hand type calcineurin B-like protein (CBL) and functioned in sensing the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration by direct binding to Ca2+. Indeed, the loss-of-function sos3-1 mutation reduced its Ca2+ binding capacity, indicating that Ca2+ sensing by SOS3 is an essential mechanism for salt tolerance in plant (Sanchez-Barrena et al. 20042005). The Ca2+ bound CBL proteins directly activate their interacting CIPK (CBL-interacting protein kinase) proteins. As a SOS3 interacting CIPK, SOS2 (Salt Overlay Sensitive2) was identified, and the activation of kinase activity of SOS2 by SOS3 was in a Ca2+ dependent manner (Halfter et al. 2000; Liu et al. 2000). Also, SOS2 interacts and activates vacuolar N+/H+ and H+/Ca2+ antiporters and V-ATPase independently of SOS3 leading to sequestration of excess Na+ ion into vacuoles and maintain cytosolic Ca2+ level (Qiu et al. 2004; Ji et al. 2013). SOS pathway is conserved in rice and a Na+/H+ antiporter, OsSOS1, was shown that OsSOS1 in the plasma membrane of yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) cells reduced total Na+ content in the cell. Other SOS2 and SOS3 homologs in rice were also identified as OsCIPK24 and OsCBL4, respectively (Atienza et al. 2007). Xiang et al. (2007) surveyed 30 putaitive CIPK genes from rice genome and found many of them showed stress responsive expression. Among those, they showed that OsCIPK15-ox transgenic rice have significantly improved tolerance to salt stress. These suggest that Ca2+ spiking by salt stress triggers the SOS3-SOS2 mediated salt stress signaling pathways. Further, these demonstrate that the high degree of functional conservation of Ca2+-mediated sodium ion homeostasis is well evolved in monocot and dicot plants. More detailed studies on the precise roles of rice SOS pathways will be necessary to extend our understanding in the molecular mechanisms of maintaining an osmotic adjustment or homeostasis. These efforts will be very helpful for developing biotechnological tools to increase osmotic and salt tolerances of crop plants.

Abscisic acid (ABA)

Plant stress hormone ABA has long been considered as an essential phytohormone for regulating various plant developmental processes as well as the adaptive responses to broad range of abiotic stresses (Zhu 2002 Hadiarto and Tran 2011). Indeed, the endogenous level of ABA and its biosynthetic genes in plant is rapidly increased by abiotic stresses including drought and salt stress. The elevated ABA hormone aids plant to acclimate under lower water availability by closing guard cells and accumulating numerous proteins for osmotic adjustment. Interestingly, the expression of many ABA biosynthetic genes seems to be regulated by a stress-induced Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation and its signaling pathways in rice (Du et al. 2010; Saeng-ngam et al. 2012). For example, overexpression of drought-responsive OsDSM2 (Drought-hypersensitive mutant2) and OsCam1-1 genes led to accumulation of ABA and tolerance to salt stress in rice. OsDSM2 and OsCam1-1 genes encode an ABA biosynthetic β-carotene hydrolase and a Ca2+-binding calmodulin, respectively (Du et al. 2010; Saeng-ngam et al. 2012). These results suggest that stress-activated Ca2+ spiking could provide the positive feedback loop for ABA biosynthesis, and this event might be critical for stress tolerance in rice.

Jasmonate (JA)

JA including Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) and its free-acid form, JA, is an important signaling molecule for diverse developmental processes and defense responses (Kazan and Manners 2012). Several studies have investigated biological relevancies of JA signaling in salt stress in rice. Interestingly, higher endogenous JA contents were observed in salt-tolerant cultivar rice than in salt-sensitive cultivar (Kang et al. 2005). In addition, MeJA level was increased by high salt stress in rice (Moons et al. 1997), supposing that high accumulation of JA in rice could be an effective protection against salt stress. Consistently, exogenous JA treatment dramatically reduced the Na+ ions in salt-tolerant cultivar rice (Kang et al. 2005).

Recent findings showed some evidences of crosstalk between ABA and Jasmonate (JA) in regulating salt stress (Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki 2007). JA is involved in development and plant defense responses through modulating JAZ (Jasmonate ZIM-domain) transcription factors. Interestingly, MYC2 transcription factors are commonly used for regulating gene expression of JA, ABA and salt stress. JA induces proteolysis of JAZ which functions in direct repressing MYC2, thereby enabling MYC2 transcription factors to activate the downstream target gene expressions (Kazan and Manners 2012). This suggests that JA plays important roles in ABA-dependent regulation of salt stress responsive genes. Several rice JAZ proteins such as OsTIFY1, 6, 9, 10 and 11 have been identified as salt-inducible genes (Ye et al. 2009). However, the antagonistic roles of JA in ABA-mediated regulations of salt-stress related gene expressions have been also reported in rice root. JA treatment effectively reduced the ABA-mediated up-regulation of OsLEAs in rice root. Furthermore, JA-inducible genes were not stimulated in the presence of JA and ABA (Moons et al. 1997). Taken together, this implies the involvement of different regulation mechanisms in JA and ABA-mediated responses to salt stress.

Brassinosteroids (BRs)

Plant steroid hormone BRs play essential roles in diverse plant developmental processes and stress tolerances (Vriet et al. 2012). Recently, many studies have demonstrated the positive roles of BR applications or endogenous BR contents in salt and drought stress in plant (Koh et al. 2007; Manavalan et al. 2012). BRs positively regulate salt stress responses in rice. A T-DNA inserted loss-of-function rice gsk1 mutant, an orthologous gene of a BR negative regulator, BIN2, showed an increased tolerance to salt stress compared to wild type rice (Koh et al. 2007). Furthermore, exogenous BR application could remove the salinity-induced inhibition of seed germination and seedling growth in rice. Consistently, increasing endogenous sterol contents in rice by RNAi-mediated disruption of the rice SQS (Squalene synthase) gene led to decreasing stomata density and increasing drought stress tolerance (Manavalan et al. 2012). These results describe the role of BRs in tolerance to salt and drought stress. Nonetheless, the molecular mechanisms for BR-mediated salt stress tolerance are still unclear. Some possible molecular mechanisms linked BRs with salt stress acclimation were recently demonstrated. BRs might enable plant to resist salt stress condition by reducing stomatal conductance and ER stress signaling (Che et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2012). BR signaling pathways reduced the stomata density by suppressing the BIN2 triggered inactivation of YDA-mediated stomata development signaling cascades (Kim et al. 2012), indicating that higher BR activity could decrease water loss under drought and salt stress conditions. Another possibility of BR-mediated salt stress tolerance was reported (Che et al. 2010). RIP (Regulated intermembrane proteolysis) of miss-folding proteins occurred in ER by diverse stress conditions is well conserved mechanisms in eukaryotes. Two RIP related bZIP transcription factors are tightly linked with BR signaling pathways and this link is required for acclimation to numerous stresses (Che et al. 2010), suggesting the prominent roles of BRs in salt stress tolerances via ER stress signaling pathways.

Genomics of osmoprotectants

Severe osmotic stresses, salinity, drought, and cold, cause detrimental changes in cellular components. Accumulation of certain organic solutes (known as osmoprotectants) is a common metabolic adaptation found in diverse plant species. The osmoprotectants have been definitely proven to be among the most important factors to protect plant cells from dehydration and salinity (Rontein et al. 2002; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki 2002). The organic solutes protect plants from abiotic stress by osmotic adjustment, detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and stabilization of the quaternary structure of proteins (Bohnert and Jensen 1996). Transgenic plants overexpressing the genes participating in the synthesis or accumulation of osmoprotectants that function for osmotic adjustment, such as proline (Kishor et al. 1995), glycinebetaine (Holmström et al. 2000) or other osmolytes show increased salt tolerance. The most important plant osmoprotectants are proline, glycine betaine, trehalose and myo-inositol. An important feature of osmoprotectants is that their beneficial effects are generally not species-specific, so that alien osmoprotectants can be engineered into plants and protect their new host.

Proline

Proline as an amino acid is essential for primary metabolism in plants during salt and drought stresses, showing a molecular chaperone role due to its stabilizing action either as a buffer to maintain the pH of the cytosolic redox status of the cell (Verbruggen and Hermans 2008; Kido et al. 2013) or as antioxidant through its involvement in the scavenging of free highly reactive radicals (Smirnoff and Cumbes 1989) or acting as a singlet oxygen quencher (Bhalu and Mohanty 2002). In higher plants, proline biosynthesis may proceed either via glutamate, by successive reductions catalyzed by pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase (P5CS) and pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase (P5CR) or by ornithine pathway and ornithine d-aminotransferase (OAT), representing generally the first activated osmoprotectant after stress perception (Savouré 1995; Parida et al. 2008).

Proline accumulation in transgenic rice plants with P5CS cDNA was reported and proved stress-induced overproduction of the P5CS enzyme under salinity stress (Zhu et al. 1998; Lee et al. 2012). A cDNA clone encoding P5CS was later isolated from rice and characterized. The expression of P5CS and the accumulation of proline in salt tolerant cultivar are much higher than in salt sensitive lines (Igarashi et al. 1997). When P5CS gene was overexpressed in the transgenic tobacco plants, an increased production of proline coupled with salinity tolerance were noted (Kishor et al. 1995). Thus, P5CS may not be the rate-limiting step in proline accumulation (Delauney and Verma 1993).

Glycine betaine

Betaines are amino acid derivatives in which the nitrogen atom is fully methylated such as that of quaternary ammonium compounds. Among the many quaternary ammonium compounds known in plants, glycine betaine (GB) occurs most abundantly in response to dehydration stress (Yang et al. 2003) where it reduces lipid peroxidation, thereby helps in maintaining the osmotic status of the cell to ameliorate the abiotic stress effect (Chinnusamy et al. 2005). In higher plants, glycine betaine is synthesized in the chloroplast from serine via choline by the action of choline monooxygenase (CMO) and betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase (BADH) enzymes (Ashraf and Foolad 2007).

Genes involved in osmoprotectant biosynthesis are upregulated under salt stress, and the concentrations of accumulated osmoprotectants correlates with osmotic stress tolerance (Chen and Murata 2002; Zhu 2002). Choline dehydrogenase gene (codA) from Arthrobacter globiformis aids in improving the salinity tolerance in rice (Vinocur and Altman 2005).

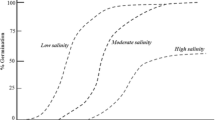

Tolerant genotypes normally accumulate more glycine betaine than sensitive genotypes in response to stress. This relationship, however, is not universal. The osmolyte that plays a major role in osmotic adjustment is species dependent. Some plant species such as rice (Oryza sativa), mustard (Brassica spp.), Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) naturally do not produce glycine betaine under stress or non-stress conditions (Rhodes and Hanson 1993). In these species, transgenic plants with overexpressing glycine betaine synthesizing genes exhibited abundant production of glycine betaine, which leads plants to tolerate stresses, including salinity stress (Rhodes and Hanson 1993). The limitation in production of glycine betaine in high quantities in transgenic plants is reportedly due to either low availability of substrate choline or reduced transport of choline into the chloroplast where glycine betaine is naturally synthesized (Huang et al. 2000). Thus, to engineer plants for overproduction of osmolytes such as glycine betaine , other factors such as substrate availability and metabolic flux must also be considered.

In rice indica plant (cv. IR36), deficiency of glycine betaine has been attributed to the absence of the two enzymes, choline monooxygenase and betaine aldehyde, in the biosynthetic pathway (Rathinasabapathi et al. 1993). However, the enzymatically active BADH is detectable in Japonica variety of rice (cv. Nipponbare) (Nakamura et al. 1997). This apparent discrepancy is yet subject for further investigation. Exogenous foliar application of glycine betaine to Oryza sativa (Harinasut et al. 1996) resulted in improved growth of plants under salinity stress condition. Further, a decrease in Na+ and an increase in K+ concentrations in shoots were observed in GB-treated plants under salinity. This indicates the possible role of glycine betaine in signal transduction and ion homeostasis as well.

Trehalose

Trehalose is a non-reducing disaccharide in which two glucose molecules are joined together by a glycosidic -(1–1) bond. In plants, the synthesis of this sugar occurs normally by the formation of the trehalose-6-phosphate (T6P) from the UDP-glucose and glucose-6-phosphate, a reaction catalyzed by the trehalose 6-phosphate synthase (TPS). Afterwards the T6P is dephosphorylated by the trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase (TPP) resulting in the formation of free trehalose (Wingler 2002). It has been shown that trehalose can protect proteins and cellular membranes from denaturation caused by a variety of stress conditions, including desiccation (Elbein et al. 2003).

Trehalose overproduction has considerable potential for improving abiotic stress tolerance in rice transgenic plants. Increased trehalose accumulation showed higher level of tolerance to salt, drought, and low-temperature stresses, as compared with the nontransformed controls (Garg et al. 2002). Trehalose may ameliorate salinity stress through stabilization of the plasma membranes, since it decreased the rate of ion leakage and the rate of lipid peroxidation of the root cells, and increased the ratio of K+/Na+ ions in the leaves of maize seedlings (Zeid 2009).

Myo-inositol

Inositol is a cyclohexanehexol, a cyclic carbohydrate with six hydroxyl groups, one on each carbon ring. Among the nine types of existing steroisomers, myo-inositol is the most abundant in the nature, being also important for the biosynthesis of a wide variety of compounds including inositol phosphates, glycosylphosphatidylinositols, phosphatidylinositides, inositol esters, and ethers in plants (Murthy 2006). Myoinositol serves as a substrate for the formation of galactinol, the galactosyl-donor that plays a key role in the formation of raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs, raffinose, stachyose, verbascose) from sucrose. RFOs accumulate in plants under different stress conditions (Peters et al. 2007). In the case of the halophyte Mesembryanthemum crystallinum (common ice plant) - that possesses a remarkable tolerance against drought, high salinity, and cold stress inositol is methylated to D-ononitol and subsequently epimerized to D-pinitol. This plant accumulates a large amount of these inositol derivatives during the stress (Vernon et al. 1993). Due to the potential of myo-inositol, some transgenic plants expressing this substance have been generated, mainly using MIPS enzyme or inositol derived enzymes. Isolation of the PINO1 gene (also known as PcINO1, encoding an l-myo-inositol 1-phosphate synthase) from the wild halophytic rice relative Porteresia coarctata and transformation in tobacco has been reported (Majee et al. 2004). This gene conferred tobacco plants tolerance to 200–300 mM NaCl keeping up 40–80% of the photosynthetic competence with concomitant increased inositol production, which is significantly better than the unstressed control. Additionally, PINO1 transgenics showed in vitro salt-tolerance, complementing in planta functional expression of this gene.

Genomic overview of transporters in rice salt response

Various channels, carriers and pumps are working for the ion homeostasis in the cell and salt stress causes ions unbalance (Figure 3). In rice, 1,200 transporter proteins have been annotated from the genome sequence, among which 84% are active transporters (Nagata et al. 2008). Here we briefly reviewed ion transporters involved in the salt tolerance.

Schematic diagram of a plant cell showing regulation of ion homeostasis by various ion transporters. The salinity stress signal is perceived by receptor(s) or salt sensor(s) probably present at the plasma membrane of the cell. The signal is responsible for activating the SOS pathway, the component of which helps in regulating some of these transporters. The transporters are K+ inward-rectifying channel (OsAKT1), K+/Na+ symporter (OsHKT1), nonselective cation channel (NCC), K+ outward-rectifying channel (OsKCO1), Na+/H+ antiporters (OsSOS1), vacuolar Na+/H+ exchangers (OsNHX1-4), endosomal Na+/H+ exchanger (OsNHX5), H+/Ca+ antiporter (OsCAX1) and vacuolar chloride channel (OsCLC1). Na+ extrusion from plant cells is powered by the electrochemical gradient generated by H+-ATPases, which permits the Na+/H+ antiporters to couple the passive movement of H+ inside along the electrochemical gradient and extrusion of Na+ out of cytosol. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; TGN/EE, trans-Golgi network/early endosome; LE/PVC/MVB, late endosome/pre-vacuolar compartment/multivesicular body; RE, recycling endosome. The stress signal sensed by SOS3 activates SOS2, which activates SOS1, details is given in the text.

Na+/H+ antiporters

The importance of Na+ transporters for Na+ tolerance in plant was first known in sugar beets (Blumwald and Poole, 1987). Activity and function of Na+/H+ antiporters, major Na+ transporters in plants, have been studied in various plants including rice and Arabidopsis. In Arabidopsis, the plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter (SOS1) regulates sodium efflux in roots and the long-distance transport of sodium from roots to shoots (Wu et al. 1996). A functional homologue of SOS1 in rice, OsSOS1, had been isolated and a T-DNA insertion mutant of OsSOS1 exhibited a salt sensitivity. It has been reported that SOS1 proteins contain self-inhibitory domains at their carboxy termini and the truncation of this inhibitory domain in OsSOS1 resulted in a much greater Na+ transport activity with enhanced salt tolerance in yeast cells (Atienza et al. 2007). In rice genome 13 antiporters are retrieved through in silico analysis, nine of which are Na+/H+ antiporters and 4 are K+/H+ antiporters, whereas 35 antiporters were retrieved in Arabidopsis with 29 being Na+/H+ antiporters and 6 K+/H+ antiporters.

In rice, 4 vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporters (OsNHX1-4) and one endosomal Na+/H+ antiporter (OsNHX5) have been reported (Bassil et al. 2012). OsNHX3 was showed to be phosphorylated at S471 in the C-terminus, a residue that is conserved in other vacuolar isoforms, suggesting that S471 is important for the activation of the antiporters. Overexpression of OsNHX1 in rice and in maize improved salt tolerance by enhancing the compartmentalization of Na+ into the vacuoles (Chen et al. 2007). Ca2+/H+ antiporter (CAX) is a pump which helps intracellular Ca2+ ion homeostasis (Figure 3). From rice genome sequence four CAX genes (OsCAX1a, OsCAX1b, OsCAX2 and OsCAX3) and OsCAX1c, a pseudogene of CAX1, were retrived. Expression of all rice CAX genes except OsCAX2 showed Ca2+ tolerance in yeast (Kamiya et al. 20042005). It is noticeable that in a salt tolerant rice cultivar Fl, the expression of a CAX-type exchanger was down-regulated compared to that of a salt sensitive cultivar RI, suggesting that the down-regulation of the CAX exchanger may be related to salt tolerance (Senadheera et al. 2009). However it is yet unknown whether or not CAX genes play direct role in the salt stress tolerance in rice.

Na+/K+ symporter

HKT is a Na+/K+ symporter or Na+ uniporter present in the plasma membrane of plant cells. Rice genome has seven HKT transporter genes and two pseudogenes whereas Arabidopsis has 16 HKT transporter genes (Garciadeblas et al. 2003 Platten et al. 2006). Horie et al. (2007) reported that oshkt2;1 mutant showed significant growth defect when a moderate amount of Na+ exists in K+- deficient condition. These results indicated that the OsHKT2;1-dependent Na+ influx in K+- deficient roots is regulated to prevent Na+ toxicity due to mass flow of Na+ through OsHKT2;1 (Figure 2.) A QTL, SKC1, from a salt tolerant variety which maintained K+ homeostasis under salt stress was mapped (Ren et al., 2005). Isolation of SKC1 gene, which encodes HKT-type Na+-transporter suggested the role of SKC1 in K+/Na+ homeostasis under salt stress.

H+-ATPase are primary active transporters. An electrochemical gradient generated by H+-ATPase helps in Na+ extrusion out of the cytosol. In silico analysis of rice genome revealed that 11 H+-ATPases are present in the vacuole, plasma membrane and Trans Golgi Network (TGN). In Arabidopsis, mutant lacking vacuolar V-H+-ATPase subunits showed a reduced tonoplast V-ATPase activity, but did not show sensitivity to high salinity (Krebs et al. 2010). However, a knockout of an endosomal (EE/TGN) V-H+-ATPase mutant showed increased salt sensitivity, indicating the importance of the endosomal system for the salt tolerance. In rice, expression of H+-ATPase gene, OSA3, under salt stress was greatly induced in a salt-tolerant mutant M-20, but not in a salt-sensitive variety 77–170, suggesting an active role of OSA3 in relation with salt stress tolerance. However, there is no direct evidence that any of H+-ATPases in rice are involved in the salt stress tolerance.

Channel protein

Several channel proteins are also involved in salt stress response in rice. Nonselective cation channels (NCCs) are proposed as an entry gate of Na+ into the plant cell. It was hypothesized that NCCs play a significant role in root Na+ uptake because of similarity between Na+ current and Ca2+ inhibition of radioactive Na+ influx (Demidchik et al. 2007). However, the exact conductance and proportion of this pathway may vary. Chloride ions are also important for salt stress response and chloride channel (CLC) although other channels are also involved in chloride transport. In silico analysis revealed that rice genome has 9 chloride channel (CLC) genes. Those channel proteins are present in vacuole, Golgi body and chloroplast. A salt stress inducible OsCLC1 was identified from rice and the OsCLC1 was shown to operate as anion channels in one system, but H+/Cl- antiporter in another (Nakamura et al. 2006). Although there is no direct evidence that OsCLC genes have roles in the salt stress tolerance, a comparison study revealed that there was a genotype-dependent differences in expression of OsCLC1. Under salt stress, salt-sensitive IR29 had repressed expression of OsCLC1, while salt-tolerant Pokkali showed induction particularly in roots, suggesting that the level of OsCLC1 expression is correlated to the salt tolerance (Diedhiou and Golldack 2006). Inward-rectifying K+ channels (KIRC) mediates the influx of K+ on the plasma membrane and it selectively accumulates K+ over Na+ upon the plasma membrane hyperpolarization (Muller-Rober et al. 1995; Golldack et al. 2003). In rice genome, 15 are retrieved in silico compared to 12 in Arabidopsis. A few KIRC-encoding genes (AKT) have been functionally characterized. Salt stress inhibited OsAKT1 gene expression and the inward K+ influx was significantly decreased in root protoplasts by salt stress, suggesting that OsAKT1 is a dominant salt-sensitive K+ uptake channel (Fuchs et al. 2005). Recently, it was shown that overexpression of a bHLH-type transcription factor gene OrbHLH001 in transgenic rice increased the salt tolerance of transgenic rice with increased level of OsAKT1 gene expression (Chen et al. 2013). More detailed studies on the precise roles of rice transporter genes will be helpful in understanding the molecular mechanisms of maintaining an osmotic adjustment or homeostasis and these efforts will be helpful for developing salt tolerant rice plants.

Conclusion

Availability of high quality rice genome sequence fast tracked the progress made in functional genomics of salinity tolerance in rice. This aids in the discovery of several genes that could be deployed for use in breeding for rice salt tolerance. The complex mechanism underlying salt tolerance as well as the complex nature of salt stress itself and the wide range of plant responses make the trait unexplainable. Even so, several evidences showed that members of protein families involved in signal transduction, osmoregulation, ion transportation and protection from oxidative damage are critical in governing high salt tolerance (Figure 2). Various multiple signaling pathways can be activated during exposure to stress, leading to similar responses to different stimuli which suggest the overlap in gene expression between environmental stresses. Rice exhibits cellular ion homeostasis and enormous genetic variability in its sensitivity to salt stress. The indica varieties Pokkali and Nonabokra have higher endogenous ABA level during osmotic shock and are classified as highly salt tolerant ecotypes. To maximize the productivity of rice under saline soils there is an urgent need to look for sources of genetic variation that can be used for developing new cultivars with greater yield potential and stability over seasons and ecogeographic locations. Identification of molecular markers associated with salt stress tolerance genes or QTL conferring tolerance to high salinity has been demonstrated. Significant breakthroughs have been made on the mechanism and control of salinity stress tolerance in rice, but large gaps about our understanding in this field remained to be explored. Thus, further investigations are needed to sufficiently explain the underlying mechanisms of protection of rice under salt stress condition. Identification of the role of different component providing salt stress and the cross talks between these components will be a future challenge to disentangle the complete genome network of rice providing salinity tolerance. An emerging scope to identify novel cis-acting elements and elements acting in tandem may possibly lead to unraveling the complex web pattern for salinity signaling. Apparently, development of plants with improved tolerance to salt remained a big challenge despite the significant progress in genomics of salt tolerance in rice.

References

Agrawal GK, Rakwa R, Iwahashi H: Isolation of novel rice (Oryza sativa L.) multiple stress responsive MAP kinase gene, OsMSRMK2, whose mRNA accumulates rapidly in response to environmental cues. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2002, 294: 1009–1016. 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00571-5

Agrawal GK, Agrawal SK, Shibato J, Iwahashi H, Rakwal R: Novel rice MAP kinases OsMSRMK3 and OsWJUMK1 involved in encountering diverse environmental stresses and developmental regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003, 300: 775–783. 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02868-1

Asano T, Hakata M, Nakamura H, Aoki N, Komatsu S, Ichikawa H, Hirochika H, Ohsugi R: Functional characterisation of OsCPK21, a calcium-dependent protein kinase that confers salt tolerance in rice. Plant Mol Biol 2011, 75: 179–191. 10.1007/s11103-010-9717-1

Asano T, Hayashi N, Kobayashi M, Aoki N, Miyao A, Mitsuhara I, Ichikawa H, Komatsu S, Hirochika H, Kikuchi S, Ohsugi R: A rice calcium-dependent protein kinase OsCPK12 oppositely modulates salt-stress tolerance and blast disease resistance. Plant J 2012, 69: 26–36. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04766.x

Ashraf M, Foolad MR: Roles of glycine betaine and proline in improving plant abiotic stress resistance. Environ Exp Bot 2007, 59: 206–216. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2005.12.006

Atienza JM, Jiang X, Garciadeblas B, Mendoza I, Zhu JK, Pardo JM, Quintero FJ: Conservation of the salt overly sensitive pathway in rice. Plant Physiol 2007, 143: 1001–1012.

Bassil E, Coku A, Blumwald E: Cellular ion homeostasis: emerging roles of intracellular NHX Na+/H+ antiporters in plant growth and development. J Exp Bot 2012, 63: 5727–5740. 10.1093/jxb/ers250

Bhalu B, Mohanty P: Molecular mechanisms of quenching of reactive oxygen species by proline under stress in plants. Curr Sci 2002, 82: 525–532.

Blumwald E, Poole R: Salt-tolerance in suspension cultures of sugar beet. Induction of Na+/H+-antiport activity at the tonoplast by growth in salt. Plant Physiol 1987, 83: 884–887. 10.1104/pp.83.4.884

Bohnert HJ, Jensen RG: Strategies for engineering water-stress tolerance in plants. Trends Biotech 1996, 14: 89–97. 10.1016/0167-7799(96)80929-2

Che P, Bussell JD, Zhou W, Estavillo GM, Pogson BJ, Smith SM: Signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum activates brassinosteroid signaling and promotes acclimation to stress in Arabidopsis. Sci Signal 2010, 3: ra69. 10.1126/scisignal.2001140

Chen TH, Murata N: Enhancement of tolerance of abiotic stress by metabolic engineering of betaines and other compatible solutes. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2002, 5: 250–257. 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00255-8

Chen M, Chen QJ, Niu XJ, Zhang R, Li HQ, Xu CY, et al.: Expression of OsNHX1 gene in maize confers salt tolerance and promotes plant growth in the field. Plant Soil Environ 2007, 53: 490–498.

Chen Y, Lia F, Maa Y, Chong K, Xu Y: Overexpression of OrbHLH001, a putative helix–loop–helix transcription factor, causes increased expression of AKT1 and maintains ionic balance under salt stress in rice. J Plant Physiol 2013, 170: 93–100. 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.08.019

Chinnusamy V, Jagendorf A, Zhu JK: Understanding and improving salt tolerance in plants. Crop Sci 2005, 45: 437–448. 10.2135/cropsci2005.0437

Chinnusamy V, Zhu J, Zhu JK: Gene regulation during cold acclimation in plants. Physiol Plant 2006, 126: 52–61. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2006.00596.x

Chung PJ, Kim YS, Jeong JS, Park SH, Nahm BH, Kim JK: The histone deacetylase OsHDAC1 epigenetically regulates the OsNAC6 gene that controls seedling root growth in rice. Plant J 2009, 59: 764–776. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03908.x

Cournac L, Latouche G, Cerovic Z, Redding K, Ravenel J, Peltier G: In vivo interactions between photosynthesis, mitorespiration, and chlororespiration in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 2002, 129: 1921–1928. 10.1104/pp.001636

Dai X, Xu Y, Ma Q, Xu W, Wang T, Xue Y, Chong K: Overexpression of an R1R2R3 MYB gene, OsMYB3R-2, increases tolerance to freezing, drought, and salt stress in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2007, 143: 1739–1751. 10.1104/pp.106.094532

Darwish E, Testerink C, Khalil M, El-Shihy O, Munnik T: Phospholipid signaling responses in salt-stressed rice leaves. Plant cell physiol 2009, 50: 986–997. 10.1093/pcp/pcp051

Delauney AJ, Verma DPS: Proline biosynthesis and osmoregulation in plants. Plant J 1993, 4: 215–223. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1993.04020215.x

Demidchik V, Maathuis FJ: Physiological roles of nonselective cation channels in plants: from salt stress to signalling and development. New Phytol 2007, 175: 387–404. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02128.x

DeWald DB, Torabinejad J, Jones CA, Shope JC, Cangelosi AR, Thompson JE, Prestwich GD, Hama H: Rapid accumulation of phos-phatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate correlates with calcium mobilization in salt-stressed Arabidopsis. Plant physiol 2001, 126: 759–769. 10.1104/pp.126.2.759

Diedhiou CJ, Golldack D: Salt-dependent regulation of chloride channel transcripts in rice. Plant Sci 2006, 170: 793–800. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.11.014

Diedhiou CJ, Popova OV, Dietz KJ, Golldack D: The SNF1-type serine-threonine protein kinase SAPK4 regulates stress-responsive gene expression in rice. BMC Plant Biol 2008, 8: 49. 10.1186/1471-2229-8-49

Drobak BK, Watkins PA: Inositol (1,4,5) trisphosphate production in plant cells: an early response to salinity and hyperosmotic stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000, 481: 240–244.

Du H, Wang N, Cui F, Li X, Xiao J, Xiong L: Characterization of the beta-carotene hydroxylase gene DSM2 conferring drought and oxidative stress resistance by increasing xanthophylls and abscisic acid synthesis in rice. Plant Physiol 2010, 154: 1304–1318. 10.1104/pp.110.163741

Duan J, Cai W: OsLEA3–2, an abiotic stress induced gene of rice plays a key role in salt and drought tolerance. PLoS One 2012, 79: e45117.

Dubouzet JG, Sakuma Y, Ito Y, Kasuga M, Dubouzet EG, Miura S, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K: OsDREB genes in rice, Oryza sativa L. encode transcription activators that function in drought, high salt and cold-responsive gene expression. Plant J 2003, 33: 751–763. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01661.x

Elbein AD, Pan YT, Pastuszak I, Carroll D: New insights on trehalose: a multifunctional molecule. Glycobiology 2003, 13: 17R-27. 10.1093/glycob/cwg047

FAO: High level expert forum - how to feed the world in 2050. Economic and social development department. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations; 2009.

Fu SF, Chou WC, Huang DD, Huang HJ: Transcriptional regulation of a rice mitogen-activated protein kinase gene, OsMAPK4, in response to environmental stresses. Plant Cell Physiol 2002, 43: 958–963. 10.1093/pcp/pcf111

Fuchs I, Stolzle S, Ivashikina N, Hedrich R: Rice K+ uptake channel OsAKT1 is sensitive to salt stress. Planta 2005, 221: 212–221. 10.1007/s00425-004-1437-9

Gao P, Bai X, Yang L, Lv D, Li Y, Cai H, Ji W, Guo D, Zhu Y: Over-expression of osa-MIR396c decreases salt and alkali stress tolerance. Planta 2010, 231: 991–1001. 10.1007/s00425-010-1104-2

Gao P, Bai X, Yang L, Lv D, Pan X, Li Y, Cai H, Ji W, Chen Q, Zhu Y: osa-MIR393 : a salinity and alkaline stress-related microRNA gene. Mol Biol Rep 2011, 38: 237–242. 10.1007/s11033-010-0100-8

Garciadeblas B, Senn ME, Banuelos MA, Rodriguez-Navarro A: Sodium transport and HKT transporters: the rice model. Plant J 2003, 34: 788–801. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01764.x

Garg AK, Kim JK, Owens TG, Ranwala AP, Choi YD, Kochian LV, Wu RJ: Trehalose accumulation in rice plants confers high tolerance levels to different abiotic stresses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002, 99: 15898–15903. 10.1073/pnas.252637799

Golldack D, Quigley F, Michalowski CB, Kamasani UR, Bohnert HJ: Salinity stress tolerant and sensitive rice (Oryza sativa L.) regulate AKT1-type potassium channel transcripts differently. Plant Mol Biol 2003, 51: 71–81. 10.1023/A:1020763218045

Hadiarto T, Tran LS: Progress studies of drought-responsive genes in rice. Plant Cell Rep 2011, 30: 297–310. 10.1007/s00299-010-0956-z

Halfter U, Ishitani M, Zhu JK: The Arabidopsis SOS2 protein kinase physically interacts with and is activated by the calcium-binding protein SOS3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000, 97: 3735–3740. 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3735

Harinasut P, Tsutsui K, Takabe T, Nomura M, Kishitani S: Exogenous glycine betaine accumulation and increased salt tolerance in rice seedlings. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 1996, 60: 366–368. 10.1271/bbb.60.366

Holmström KO, Somersalo S, Mandal A, Palva TE, Welin B: Improved tolerance to salinity and low temperature in transgenic tobacco producing glycine betaine. J Exp Bot 2000, 51: 177–185. 10.1093/jexbot/51.343.177

Horie T, Costa A, Kim TH, Han MJ, Horie R, Leung HY, Miyao A, Hirochika H, An G, Schroeder JI: Rice OsHKT2;1 transporter mediates large Na+ influx component into K+-starved roots for growth. EMBO J 2007, 26: 3003–3014. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601732

Hoshida H, Tanaka Y, Hibino T, Hayashi Y, Tanaka A, Takabe T, Takabe T: Enhanced tolerance to salt stress in transgenic rice that overexpresses chloroplast glutamine synthetase. Plant Mol Biol 2000, 43: 103–111. 10.1023/A:1006408712416

Hossain MA, Cho JI, Han M, Ahn CH, Jeon JS, An G, Park PB: The ABRE binding bZIP transcription factor OsABF2 is a positive regulator of abiotic stress and ABA signaling in rice. J Plant Physiol 2010, 167: 1512–1520. 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.05.008

Hou X, Xie K, Yao J, Qi Z, Xiong L: A homolog of human ski-interacting protein in rice positively regulates cell viability and stress tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106: 6410–6415. 10.1073/pnas.0901940106

Hu H, Dai M, Yao J, Xiao B, Li X, Zhang Q, et al.: Overexpressing a NAM, ATAF, and CUC (NAC) transcription factor enhances drought resistance and salt tolerance in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006, 103: 12987–12992. 10.1073/pnas.0604882103

Huang J, Hirji R, Adam L, Rozwadowski KL, Hammerlindl JK, Keller WA, Selvaraj G: Genetic engineering of glycinebetaine production toward enhancing stress tolerance in plants: metabolic limitations. Plant Physiol 2000, 122: 747–756. 10.1104/pp.122.3.747

Huang XY, Chao DY, Gao JP, Zhu MZ, Shi M, Lin HX: A previously unknown zinc finger protein, DST, regulates drought and salt tolerance in rice via stomatal aperture control. Genes Dev 2009, 23: 1805–1817. 10.1101/gad.1812409

Igarashi Y, Yoshiba Y, Sanada Y, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Wada K, Shinozaki K: Characterization of the gene for Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthatase and correlation between the expression of the gene and salt tolerance in Oryza sativa. Plant Mol Biol 1997, 33: 857–865. 10.1023/A:1005702408601

Jan A, Maruyama K, Todaka DS, Abo M, Yoshimura E, Shinozaki K, Nakashima K, Shinozaki KY: OsTZF1, a CCCH-tandem zinc finger protein, confers delayed senescence and stress tolerance in rice by regulating stress-related genes. Plant Physiol 2013, 161: 1202–1216. 10.1104/pp.112.205385

Jeon J, Kim J: Cold stress signaling networks in Arabidopsis. J Plant Biol 2013, 56: 69–76. 10.1007/s12374-013-0903-y

Jeong MJ, Lee SK, Kim BG, Kwon TR, Cho WS, Park YT, Lee JO, Kwon HB, Byun MO, Park SC: A rice (Oryza sativa L.) MAP kinase gene, OsMAPK44, is involved in response to abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult 2006, 85: 151–160. 10.1007/s11240-005-9064-0

Ji H, Pardo JM, Batelli G, Oosten MJV, Bressan RA, Li X: The salt overly sensitive (SOS) pathway: established and emerging roles. Mol Plant 2013, 6: 275–286. 10.1093/mp/sst017

Kader MA, Lindberg S: Cytosolic calcium and pH signaling in plants under salinity stress. Plant Signal Behav 2010, 5: 233–238. 10.4161/psb.5.3.10740

Kamiya T, Maeshima M: Residues in internal repeats of the rice cation/H+ exchanger are involved in the transport and selection of cations. J Biol Chem 2004, 279: 812–819.

Kamiya T, Akahori T, Ashikari M, Maesshima M: Expression of the vacuolar Ca2+/H+ exchanger, OsCAX1a, in rice: cell and age specificity of expression and enhancement by Ca2+. Plant Cell Physiol 2005, 47: 96–106. 10.1093/pcp/pci227

Kang D, Seo Y, Lee JD, Ishii R, Kim KU, Shin DH, Park SK, Lee I: Jasmonic acid differentially affects growth, ion uptake and abscisic acid concentration in salt tolerant and salt sensitive rice cultivars. J Agro Crop Sci 2005, 191: 273–282. 10.1111/j.1439-037X.2005.00153.x

Kazan K, Manners JM: JAZ repressors and the orchestration of phytohormone crosstalk. Trends Plant Sci 2012, 17: 22–31. 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.10.006

Kido EA, Neto JRF, Silva RL, Belarmino LC, Neto JPB, Soares-Cavalcanti NM, Pandolfi V, Silva MD, Nepomuceno AL, Benko-Iseppon M: Expression dynamics and genome distribution of osmoprotectants in soybean: identifying important components to face abiotic stress. BMC Bioinformatics 2013, 14: S7.

Kim JA, Agrawal GK, Rakwal R, Han KS, Kim KN, Yun CH, Heu S, Park SY, Lee YH, Jwa NS: Molecular cloning and mRNA expression analysis of a novel rice (Oryza sativa L.) MAPK kinase kinase, OsEDR1, an ortholog of Arabidopsis AtEDR1, reveal its role in defense/stress signalling pathways and development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003, 300: 868–876. 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02944-3

Kim TW, Michniewicz M, Bergmann DC, Wang ZY: Brassinosteroid regulates stomatal development by GSK3-mediated inhibition of a MAPK pathway. Nature 2012, 482: 419–422. 10.1038/nature10794

Kishor PBK, Hong Z, Miao G, Hu C, Verma DPS: Overexpression of Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase increases proline production and confers osmotolerance in transgenic plants. Plant Physiol 1995, 108: 1387–1394.

Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto S, Minami H, Kagaya Y, Hattori T: Differential activation of the rice sucrose nonfermenting1-related protein kinase2 family by hyperosmotic stress and abscisic acid. Plant Cell 2004, 16: 1163–1177. 10.1105/tpc.019943

Koh S, Lee SC, Kim MK, Koh JH, Lee S, An G, Choe S, Kim SR: T-DNA tagged knockout mutation of rice OsGSK1, an orthologue of Arabidopsis BIN2, with enhanced tolerance to various abiotic stresses. Plant Mol Biol 2007, 65: 453–466. 10.1007/s11103-007-9213-4

Kong J, Gong JM, Zhang JG, Zhang JS, Chen SY: A new AOX homologous gene OsIM1 from rice (Oryza sativa L.) with an alternative splicing mechanism under salt stress. Theor Appl Genet 2003, 107: 326–331. 10.1007/s00122-003-1250-z

Krebs M, Beyhl D, Gorlich E, Al-Rasheid KAS, Marten I, Stierhof YD, Hedrich R, Schumacher K: Arabidopsis V-ATPase activity at the tonoplast is required for efficient nutrient storage but not for sodium accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010, 107: 3251–3256. 10.1073/pnas.0913035107

Kumari S, Sabharwal VP, Khushwaha HR, Sopory SK, Singla-Pareek SL, Pareek A: Transcriptome map of seedling stage specific salinity response indicate a specific set of genes as candidate for saline tolerance in Oryza sativa L. Funct Integr Genomics 2009, 9: 109–123. 10.1007/s10142-008-0088-5

Lee SK, Kim BG, Kwon TR, Jeong MJ, Park SR, Lee JW, Byun MO, Kwon HB, Matthews BF, Hong CB, Park SC: Overexpression of the mitogen-activated protein kinase gene OsMAPK33 enhances sensitivity to salt stress in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J Biosci 2011, 36: 139–151. 10.1007/s12038-011-9002-8

Lee HJ, Abdula SE, Ryu HJ, Jee MG, Jang DW, Kang KK, Cho YG: BrCIPK1 encoding CBL-interacting protein kinase 1 from Brassica rapa regulates abiotic stress responses by increasing proline biosynthesis. Chiang Mai, Thailand: 10th International Symposium on Rice Functional Genomics; 2012. OG-11 OG-11

Lee SC, Kim SH, Kim SR: Drought inducible OsDhn1 promoter is activated by OsDREB1A and OsDREB1D. J Plant Biol 2013, 56: 115–121. 10.1007/s12374-012-0377-3

Liu J, Ishitani M, Halfter U, Kim CS, Zhu JK: The Arabidopsis thaliana SOS2 gene encodes a protein kinase that is required for salt tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000, 97: 3730–3734. 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3730

Liu S, Cheng Y, Zhang X, Guan Q, Nishiuchi S, Hase K, Takano T: Expression of an NADP-malic enzyme gene in rice (Oryza sativa. L.) is induced by environmental stresses; over-expression of the gene in Arabidopsis confers salt and osmotic stress tolerance. Plant Mol Biol 2007, 64: 49–58. 10.1007/s11103-007-9133-3

Liu D, Chen X, Liu J, Ye J, Guo Z: The rice ERF transcription factor OsERF922 negatively regulates resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae and salt tolerance. J Exp Bot 2012, 63: 3899–3912. 10.1093/jxb/ers079

Lutts S, Kinet JM, Bouharmont J: Changes in plant response to NaCl during development of rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties differing in salinity resistance. J Exp Bot 1995, 46: 1843–1852. 10.1093/jxb/46.12.1843

Mahajan S, Pandey GK, Tuteja N: Calcium and salt-stress signaling in plants: shedding light on SOS pathway. Archives Biochem Biophys 2008, 471: 146–158. 10.1016/j.abb.2008.01.010

Majee M, Maitra S, Dastidar KG, Pattnaik S, Chatterjee A, Hait NC, Das KP, Majumder AL: A novel salt-tolerant L-myo-Inositol-1-phosphate synthase from Porteresia coarctata (Roxb.) Tateoka, a halophytic wild rice. J Biol Chem 2004, 279: 28539–28552. 10.1074/jbc.M310138200

Mallikarjuna G, Mallikarjuna K, Reddy MK, Kaul T: Expression of OsDREB2A transcription factor confers enhanced dehydration and salt stress tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Biotechnol Lett 2011, 33: 1689–1697. 10.1007/s10529-011-0620-x

Manavalan LP, Chen X, Clarke J, Salmeron J, Nguyen HT: RNAi-mediated disruption of squalene synthase improves drought tolerance and yield in rice. J Exp Bot 2012, 63: 163–175. 10.1093/jxb/err258

Mantri N, Patade V, Penna S, Ford R, Pang E: Abiotic stress responses in plants: present and future. In Abiotic stress responses in plants: metabolism, productivity and sustainability. Edited by: Ahmad P, Prasad MNV. New York: Springer; 2012:1–19.

Miller J, McLachlan AD, Klug A: Repetitive zinc-binding domains in the protein transcription factor IIIA from Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J 1985, 4: 1609–1614.

Moons A, Prinsen E, Bauw G, Van Montagu M: Antagonistic effects of abscisic acid and jasmonates on salt stress-inducible transcripts in rice roots. Plant Cell 1997, 9: 2243–2259.

Motohashi T, Nagamiya K, Prodhan SH, Nakao K, Shishido T, Yamamoto Y, Moriwaki T, Hattori E, Asada M, Morishima H, Hirose S, Ozawa K, Takabe T, Takabe T, Komamine A: Production of salt stress tolerant rice by overexpression of the catalase gene, katE, derived from Escherichia coli. Asia Pac J Mol Biol Biotechnol 2010, 18: 37–41.

Mukhopadhyay A, Vij S, Tyagi AK: Overexpression of a zinc-finger protein gene from rice confers tolerance to cold, dehydration, and salt stress in transgenic tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004, 101: 6309–6314. 10.1073/pnas.0401572101

Muller-Rober B, Ellenberg J, Provart N, Willmitzer L, Busch H, Becker D, Dietrich P, Hoth S, Hedrich R: Cloning and electrophysiological analysis of KST1, an inward rectrifying K+ channel expressed in potato guard cells. EMBO J 1995, 14: 2409–2416.

Munns R, Tester M: Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2008, 59: 651–681. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092911

Murthy PP: Structure and Nomenclature of Inositol Phosphates, Phosphoinositides, and Glycosylphosphatidylinositols. In Biology of Inositols and Phosphoinositides: Subcellular Biochemistry. Edited by: Biswas BB. Majumder, L. & Biswas; 2006:1–19.

Nagata T, Iizumi S, Satoh K, Kikuchi S: Comparative molecular biological analysis of membrane transport genes in organisms Plant Mol Biol. 2008, 66: 565–585.

Nakamura T, Yokota S, Muramoto Y, Tsutsui K, Oguri Y, Fukui K, Takabe T: Expression of a betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase gene in rice, a glycinebetaine nonaccumulator, and possible localization of its protein in peroxisomes. Plant J 1997, 11: 1115–1120. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11051115.x

Nakamura A, Fukuda A, Sakai S, Tanaka Y: Molecular cloning, functional expression and subcellular localization of two putative vacuolar voltage-gated chloride channels in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Physiol 2006, 47: 32–42.

Nakashima K, Tran LS, Van Nguyen D, Fujita M, Maruyama K, Todaka D, Ito Y, Hayashi N, Shinozaki K, Shinozaki KY: Functional analysis of a NAC-type transcription factor OsNAC6 involved in abiotic and biotic stress-responsive gene expression in rice. Plant J 2007, 51: 617–630. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03168.x

Nijhawan A, Jain M, Tyagi AK, Khurana JP: Genomic survey and gene expression analysis of the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family in rice. Plant Physiol 2008, 146: 333–350.

Ning J, Li X, Hicks LM, Xiong L: A raf-like MAPKKK gene DSM1 mediates drought resistance through reactive oxygen species scavenging in rice. Plant Physiol 2010, 152: 876–890. 10.1104/pp.109.149856

Ouyang SQ, Liu YF, Liu P, Lei G, He SJ, Ma B, Zhang WK, Zhang JS, Chen SY: Receptor-like kinase OsSIK1 improves drought and salt stress tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa) plants. Plant J 2010, 62: 316–329. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04146.x

Parida AK, Dagaonkar VS, Phalak MS, Aurangabadkar LP: Differential responses of the enzymes involved in proline biosynthesis and degradation in drought tolerant and sensitive cotton genotypes during drought stress and recovery. Acta Physiol Plant 2008, 30: 619–627. 10.1007/s11738-008-0157-3

Peters S, Mundree SG, Thomson JA, Farrant JM, Keller F: Protection mechanisms in the resurrection plant Xerophyta viscosa (Baker): both sucrose and raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs) accumulate in leaves in response to water deficit. J Exp Bot 2007, 58: 1947–1956. 10.1093/jxb/erm056

Platten JD, Cotsaftis O, et al.: Nomenclature for HKT transporters, key determinants of plant salinity tolerance. Trends Plant Sci 2006, 11: 372–374. 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.06.001

Purvis AC: Role of the alterantive oxidase in limiting superoxide production by plant mitochondria. Physiol Plant 1997, 100: 164–170.

Qiu QS, Guo Y, Quintero FJ, Pardo JM, Schumaker KS, Zhu JK: Regulation of Vacuolar Na+/H+ Exchange in Arabidopsis thaliana by the Salt-Overly-Sensitive (SOS) Pathway. J Biol Chem 2004, 279: 207–215.

Qiu D, Xiao J, Xie W, Liu H, Li X, Xiong L, Wang S: Rice gene network inferred from expression profiling of plants overexpressing OsWRKY13, a positive regulator of disease resistance. Mol Plant 2008, 1: 538–551. 10.1093/mp/ssn012

Rathinasabapathi B, Gage DA, Mackill DJ, Hanson AD: Cultivated and wild rice do not accumulate glycinebetaine due to deficiencies in two biosynthetic steps. Crop Sci 1993, 33: 534–538. 10.2135/cropsci1993.0011183X003300030023x

Ren ZH, Gao JP, Li LG, Cai XL, Huang W, Chao DY, et al.: A rice quantitative trait locus for salt tolerance encodes a sodium transporter. Nature Genet 2005, 37: 1141–1146. 10.1038/ng1643

Rhodes D, Hanson AD: Quaternary ammonium and tertiary sulfonium compounds in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 1993, 44: 357–384. 10.1146/annurev.pp.44.060193.002041

Rontein D, Basset G, Hanson AD: Metabolic engineering of osmoprotectant accumulation in plants. Metab Eng 2002, 4: 49–56. 10.1006/mben.2001.0208

Saeng-ngam S, Takpirom W, Buaboocha T, Chadchawan S: The role of the OsCam1–1 salt stress sensor in ABA accumulation and salt tolerance in rice. J Plant Biol 2012, 55: 198–208. 10.1007/s12374-011-0154-8

Saijo Y, Hata S, Kyozuka J, Shimamoto K, Izui K: Overexpression of a single Ca2+ dependent protein kinase confers both cold and salt/drought tolerance on rice plants. Plant J 2000, 23: 319–327. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00787.x

Sakamoto A, Alia MN: Metabolic engineering of rice leading to biosynthesis of glycinebetaine and tolerance to salt and cold. Plant Mol Biol 1998, 38: 1011–1019. 10.1023/A:1006095015717

Sakuma Y, Maruyama K, Osakabe Y, Qin F, Seki M, Shinozaki K, et al.: Functional analysis of an Arabidopsis transcription factor, DREB2A, involved in drought-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell 2006, 18: 1292–1309. 10.1105/tpc.105.035881

Sanchez-Barrena MJ, Martinez-Ripoll M, Zhu JK, Albert A: SOS3 (salt overly sensitive 3) from Arabidopsis thaliana : expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis. Acta crystallogr D Biol crystallogr 2004, 60: 1272–1274. 10.1107/S0907444904008728

Sanchez-Barrena MJ, Martinez-Ripoll M, Zhu JK, Albert A: The structure of the Arabidopsis thaliana SOS3: molecular mechanism of sensing calcium for salt stress response. J Mol Biol 2005, 345: 1253–1264. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.025

Savouré A, Jaoua S, Hua XJ, Ardiles W, Van Montagu M, Verbruggen N: Isolation, characterization, and chromosomal location of a gene encoding the delta 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett 1995, 372: 13–19. 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00935-3

Senadheera P, Singh R, Maathuis F: Differentially expressed membrane transporters in rice roots may contribute to cultivar dependent salt tolerance. J Exp Bot 2009, 60: 2553–2563. 10.1093/jxb/erp099

Shanker AK, Venkateswarlu B: Abiotic stress in plants – mechanisms and adaptations. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech Publisher; 2011:428.

Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K: Gene networks involved in drought stress response and tolerance. J Exp Bot 2007, 58: 221–227.

Singh R, Jwa NS: The rice MAPKK-MAPK interactome: the biological significance of MAPK components in hormone signal transduction. Plant Cell Rep 2013, 32: 923–931. 10.1007/s00299-013-1437-y

Singh AK, Ansari MW, Pareek A, Singla-Pareek SL: Raising salinity tolerant rice: recent progress and future perspectives. Physiol Mol Biol Plants 2008, 14: 137–154. 10.1007/s12298-008-0013-3

Singla-Pareek SL, Yadav SK, Pareek A, Reddy MK, Sopory SK: Enhancing salt tolerance in a crop plant by overexpression of glyoxalase II. Trans Res 2008, 17: 171–180. 10.1007/s11248-007-9082-2

Smirnoff N, Cumbes QJ: Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of compatible solutes. Phytochem 1989, 28: 1057–1060. 10.1016/0031-9422(89)80182-7

Song SY, Chen Y, Chen J, Dai XY, Zhang WH: Physiological mechanisms underlying OsNAC5 -dependent tolerance of rice plants to abiotic stress. Planta 2011, 234: 331–345. 10.1007/s00425-011-1403-2

Sun SJ, Guo SQ, Yang X, Bao YM, Tang HJ, Sun H, Huang J, Zhang HS: Functional analysis of a novel Cys2/His2-type zinc finger protein involved in salt tolerance in rice. J Exp Bot 2010, 61: 2807–2818. 10.1093/jxb/erq120

Takasaki H, Maruyama K, Kidokoro S, Ito Y, Fujita Y, Shinozaki K, Shinozaki KY, Nakashima K: The abiotic stress-responsive NAC-type transcription factor OsNAC5 regulates stress-inducible genes and stress tolerance in rice. Mol Genet Genomics 2010, 284: 173–183. 10.1007/s00438-010-0557-0

Tanaka Y, Hibin T, Hayashi Y, Tanaka A, Kishitani S, Takabe T, Yokota S, Takabe T: Salt tolerance of transgenic rice overexpressing yeast mitochondrial Mn-SOD in chloroplasts. Plant Sci 1999, 148: 131–138. 10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00133-8

Tao Z, Kou Y, Liu H, Li X, Xiao J, Wang S: OsWRKY45 alleles play different roles in abscisic acid signalling and salt stress tolerance but similar roles in drought and cold tolerance in rice. J Exp Bot 2011, 62: 4863–4874. 10.1093/jxb/err144

Thakur P, Kumar S, Malik JA, Berger JD, Nayyar H: Cold stress effects on reproductive development in grain crops: an overview. Environ Exp Bot 2010, 67: 429–443. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2009.09.004

Todaka D, Nakashima K, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K: Towards understanding transcriptional regulatory networks in abiotic stress responses and tolerance in rice. Rice 2012, 5: 6. 10.1186/1939-8433-5-6