Abstract

Background

Neoehrlichia mikurensis s an emerging and vector-borne zoonosis: The first human disease cases were reported in 2010. Limited information is available about the prevalence and distribution of Neoehrlichia mikurensis in Europe, its natural life cycle and reservoir hosts. An Ehrlichia-like schotti variant has been described in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks, which could be identical to Neoehrlichia mikurensis.

Methods

Three genetic markers, 16S rDNA, gltA and GroEL, of Ehrlichia schotti-positive tick lysates were amplified, sequenced and compared to sequences from Neoehrlichia mikurensis. Based on these DNA sequences, a multiplex real-time PCR was developed to specifically detect Neoehrlichia mikurensis in combination with Anaplasma phagocytophilum in tick lysates. Various tick species from different life-stages, particularly Ixodes ricinus nymphs, were collected from the vegetation or wildlife. Tick lysates and DNA derived from organs of wild rodents were tested by PCR-based methods for the presence of Neoehrlichia mikurensis. Prevalence of Neoehrlichia mikurensis was calculated together with confidence intervals using Fisher's exact test.

Results

The three genetic markers of Ehrlichia schotti-positive field isolates were similar or identical to Neoehrlichia mikurensis. Neoehrlichia mikurensis was found to be ubiquitously spread in the Netherlands and Belgium, but was not detected in the 401 tick samples from the UK. Neoehrlichia mikurensis was found in nymphs and adult Ixodes ricinus ticks, but neither in their larvae, nor in any other tick species tested. Neoehrlichia mikurensis was detected in diverse organs of some rodent species. Engorging ticks from red deer, European mouflon, wild boar and sheep were found positive for Neoehrlichia mikurensis.

Conclusions

Ehrlichia schotti is similar, if not identical, to Neoehrlichia mikurensis. Neoehrlichia mikurensis is present in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks throughout the Netherlands and Belgium. We propose that Ixodes ricinus can transstadially, but not transovarially, transmit this microorganism, and that different rodent species may act as reservoir hosts. These data further imply that wildlife and humans are frequently exposed to Neoehrlichia mikurensis- infected ticks through tick bites. Future studies should aim to investigate to what extent Neoehrlichia mikurensis poses a risk to public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The most prevalent tick-borne infection of humans in the Northern hemisphere is Lyme [1] The same tick species transmitting the etiologic agents of Lyme disease also serve as the vector of pathogens causing tick-borne encephalitis and several forms of rickettsioses, anaplasmoses and ehrlichioses [2]. Members of the family Anaplasmataceae are obligatory intracellular bacteria that reside within membrane-enclosed vacuoles. Human ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are two closely related diseases caused by various members of the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. A major difference between these two members is their cellular tropism. Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the etiologic agent of human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (HME), is an emerging zoonosis that causes clinical manifestations ranging from a mild febrile illness to a fulminant disease characterized by multi-organ system failure [3]. Anaplasma phagocytophilum causes human granulocytotropic anaplasmosis (HGA), previously known as human granulocytotropic ehrlichiosis [3]. Despite the presence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks in the Netherlands [4], only one human case has been reported [5]. Seropositivity against anaplasmosis was observed in risk groups, such as foresters and suspected Lyme disease patients, but not in control groups [6]. Still, the incidence of these tick-borne diseases and the associated public health risks remain largely unknown.

A novel candidate species in the family of Anaplasmataceae, called Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis (N. mikurensis), was first isolated from wild rats and was also found in I. ovatus in Japan [7]. Neoehrlichia mikurensis can be distinguished from other genera based on sequence analysis of 16S rDNA, citrate synthase (gltA) and heat shock protein GroEL genes [7]. This recently identified bacterium is detected in several tick species and rodents in different parts of the world under different names [7–11]. The N. mikurensis found in I. ricinus ticks in Italy has been referred to as Candidatus Ehrlichia walkerii[9] and the Ehrlichia species isolated from a rat in China was called “Rattus strain” [12]. Furthermore, a N. mikurensis has been described in I. persulcatus in Russia [13] and I. ovatus from China and Japan [12]. In the US, an Ehrlichia-like organism, closely related to N. mikurensis, was previously detected in raccoons. This variant is called Candidatus Neoehrlichia lotoris[14]. The Asian N. mikurensis isolates showed a 99% similarity based on the 16S rDNA to the Ehrlichia schotti. Ehrlichia schotti was first described in 1999 in I. ricinus in the Netherlands by Leo Schouls and was named after his technician [8]. Later this species was reported in I. ricinus in Russia [15] and subsequently in Germany and Slovakia [16]. These findings raised the question whether Ehrlichia schotti is the same as N. mikurensis.

It is unclear whether N. mikurensis poses a risk to public health. Until recently, there were no human infections reported. In 2010, the first case of human N. mikurensis infection was reported in a patient from Sweden [17]. In the same year, five other human infections were described in Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic [18]. More recently, a canine infection was reported in Germany [19]. The symptoms described in all of these cases were generally non-specific and usually seen in any other ordinary inflammation reaction (Table 1). These reported cases of human infections imply that re-evaluation is needed regarding the pathogenesis of this species. All but one case that have been described so far have occurred in patients who were immuno-compromised. The non-specificity of the reported symptoms, poor diagnostic tools and the lack of awareness of public health professionals could explain the absence of (reported) patients.

In this study we aim to investigate (i) whether Ehrlichia schotti is similar to the described N. mikurensis family, (ii) the distribution and prevalence of N. mikurensis in the Netherlands, Belgium and the UK, (iii) possible transmission routes of N. mikurensis in non-experimental settings and (vi) its putative mammalian hosts.

Methods

Collection, identification and DNA extraction of ticks

Questing I. ricinus from all stages and Dermacentor reticulatus adults were collected in 2009 and 2010 by flagging the vegetation at geographically different locations in the Netherlands and Belgium. Ticks collected in the UK and Vrouwenpolder (NL) have been described before [22]. For global geographic location, see Additional file 1: Figure S1. Questing I. arboricola were collected from bird nests in two different areas in Belgium. Ixodes hexagonus feeding on hedgehogs were collected in a hedgehog-shelter in 2010. Ixodes ricinus feeding on red deer (Cervus elaphus), European mouflon (Ovis orientalis musimon), wild boar (Sus scrofa) and sheep (Ovis aries) were collected. All the collected ticks were immersed in 70% alcohol and stored at −20°C until the DNA extraction. Based on morphological criteria, tick species and stages were identified to species level, with stage and sex recorded [23]. In doubtful cases, sequencing of tick mitochondrial 16S rDNA confirmed the tick-species [24]. DNA from questing ticks was extracted by alkaline lysis [4]. DNA from engorged ticks was extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit according to the manufacturer’s manual (Qiagen, 2006, Hilden; Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol for the purification of total DNA from ticks.

Preparation of DNA lysates from wild rodents

Longworth traps (Bolton Inc., UK), baited with hay, apple, carrot, oatmeal and mealworm were used to capture different species of rodents and insectivores at 7 different locations in the Netherlands between 2007 and 2010. Animals were anaesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by cardiac puncture. Serum was collected and stored at – 20°C. Spleen, liver, kidney, brain and other organs were collected and frozen at −80°C. DNA was extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit according to the manufacturer’s manual (Qiagen, 2006, Hilden; Germany). All animals were handled in compliance with Dutch laws on animal handling and welfare (RIVM/DEC permits).

Polymerase chain reactions

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifications were performed in a P x2 Thermal Cycler (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). The presence of Ehrlichia schotti in questing I. ricinus was studied by Reverse Line Blotting as described [25]. Fragments of the 16S rDNA, citrate synthase gene gltA, and the chaperonin GroEL of ehrlicial species were amplified from tick lysates and rodent tissue samples using novel primers and primers that were previously described (Table 2). Amplification of gltA and GroEL were both done in 50 μl reaction volumes containing 5 μl template DNA. GltA DNA was amplified using a final concentration of 800 nM of each primer, NMik fo-gltA and NMik re-gltA with the following PCR program, 15 min at 95°C, 40 cycles each consisting of 30 sec at 94°C, 25 sec at 53°C, and 10 min at 72°C. GroEL DNA was amplified using, 500 nM of each primer NMik fo-groEL and NMik re-groEL. The PCR program used is as followed: 15 min at 95°C, 40 cycles each consisting of 30 sec at 94°C, 75 sec at 49°C, and 10 min at 72°C. The nested reaction was carried out at the same temperature as the first reactions; only 25 cycles were carried out with 1 μL of the first amplification product. The HotStarTaq Polymerase Kit (Qiagen) was used for all PCR experiments. PCR products were detected by electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel stained with SYBR gold (invitrogen).

Multiplex real-time PCR

Oligonucleotide primer and probe sequences were designed to be specific for the N. mikurensis GroEL gene using Visual OMP DNA (Software, Inc., Ann Arbor, USA). Primer sequences for the N. mikurensis GroEL gene were NMikGroEL-F2a and NMikGroEL-R2b and generated a 99-bp fragment which was detected with the NMikGroEL-P2a TaqMan probe (Table 2). Sequences were evaluated on the basis of the following criteria: predicted cross-reactivity with closely related organisms, internal primer binding properties for hairpin and primer-dimer potential, length of the desired amplicon, G-C content, and melting temperatures (T m s) of probes and primers. The specificity of the N. mikurensis GroEL primers for N. mikurensis in the multiplex real-time PCR assay was tested with DNA extracted from the following microorganisms: Rickettsia rickettsii Anaplasma phagocytophilum R. helvetica Bartonella henselae Ehrlichia canis B. afzelii B. garinii, B. sensu stricto, Babesia microti, Candidatus Midichloria mitochondrii and tick lysates containing Wolbachia species[22, 25] None were amplified. Random samples of tick lysates which were N. mikurensis-positive in the Q-PCR were routinely confirmed by conventional PCR using NMik fo-gltA and NMik re-gltA primers, followed by DNA sequencing.

Optimized conditions for multiplex PCR

PCR was performed in a multiplex format with a reaction volume of 20 μl, using the iQ Multiplex Powermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, USA), in the LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System (F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Final PCR reaction concentrations were 1x iQ Powermix, primers ApMSP2F and ApMSP2R at 250 nM each, probe ApMSP2P-FAM at 125 nM, primers NMikGroEL-F2a and NMikGroEL-R2b at 250 nM each, probe NMikGroEL-P2a-RED at 250 nM, and 3 μl of template DNA. Cycling conditions were: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 60 cycles of a 5 sec denaturation at 95°C followed by a 35 sec annealing-extension step at 60°C. Ticks lysates were considered positive if the Ct-value of a proper sigmoid curve was maximally three cycles more than the highest dilution of the positive control sample.

For each PCR and real-time multiplex PCR, positive, negative controls and blank samples were included. A 10-3 to 10-5 dilution of a mixture of sequencing-confirmed N. mikurensis-positive tick lysates were used as positive controls. In order to minimize contamination, the reagent setup, the extraction and sample addition, and the real-time PCR as well as sample analysis were performed in three separate rooms, of which the first two rooms were kept at positive pressure and had airlocks.

DNA sequencing and genetic analysis

PCR amplicons were sequenced using the described primers (Table 2) and the BigDye Terminator Cycle sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Perkin Elmer, Applied Biosystems). All sequences were confirmed by sequencing both strands. Sequences were compared with sequences in Genbank using BLAST after subtraction of the primer sequences (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). The collected sequences were assembled, edited, and analysed with BioNumerics version 6.5 (Applied Maths NV, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). Resulting sequences were aligned with those from related organisms in Genbank. Phylogenetic analyses of the sequences and related organisms were conducted using the BioNumerics program using the neighbour-joining algorithm with Kimura's two-parameter model. Bootstrap proportions were calculated by the analysis of 1000 replicates for neighbour-joining trees. DNA sequences are available upon request.

Results

Comparison of Ehrlichia schotti with N. mikurensis

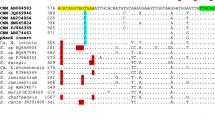

Twenty-three tick lysates that were previously tested positive for the presence of Ehrlichia schotti by PCR and Reverse Line Blotting [5, 9, 27] were amplified by PCR on the three loci 16S rDNA, gltA and GroEL using primers specific for N. mikurensis (Table 2). Amplicons of all three partial genes were obtained in 21 cases. None of these three loci were successfully amplified in 15 Ehrlichia schotti-negative ticks. The PCR products of all three loci were sequenced and compared with each other and with N. mikurensis sequences available in Genbank. All the Ehrlichia schotti sequences were identical to each other on the three loci, 16S rDNA, gltA as well as the GroEL. The 1740 base pairs of the 16S rDNA sequences from the Ehrlichia schotti were 99.6% to 100% similar to the N. mikurensis sequences and the Candidatus Ehrlichia walkerii sequence in Genbank (Table 3). The 233 base-pair fragment of the gltA sequences from the Ehrlichia schotti were identical to the Candidatus Ehrlichia walkerii gltA sequence (Table 3). The 1238 base-pairs of the GroEL isolates amplified from the tick lysates showed a 94.3% and 95.5%, 98.7% and 100% (AB084583 and AB074461, EF633745 and FJ966365) match with the N. mikurensis GroEL sequences in Genbank, respectively. Phylogenetic analyses of the gltA and GroEL sequences showed that the Ehrlichia schotti clustered with N. mikurensis isolates, but not with A. phagocytophilum or any of the Ehrlichia species present in Genbank (Figure 1).

Phylogenetic tree of the GroEL (top) and gltA (bottom) of different Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species and their relation with N. mikurensis and related species. Ehrlichia schotti/N. mikurensis sequences from I. ricinus (n = 26) and rodents (n = 11), which were generated in this study are depicted in bold. Other GroEL and gltA sequences were taken from Genbank. Their accession numbers are shown between brackets. The evolutionary distance values were determined by the method of Kimura, and the tree was constructed according to the neighbour-joining method. Bootstrap values higher than 90%, are indicated at the nodes.

Prevalence and distribution of N. mikurensis

In order to estimate the prevalence and distribution of N. mikurensis in North-West Europe, questing I. ricinus nymphs (~88%) and adults (~12%) were tested using a Q-PCR for the simultaneous detection of N. mikurensis and A. phagocytophilum. In all 12 study-areas in the Netherlands, N. mikurensis was detected with a prevalence varying from 1% to 16% (Table 4). Ticks from one study area (Duin en Kruidberg) were tested in two consecutive years. In 2009, 16% of the questing nymphs and adults I. ricinus were infected with N. mikurensis. The prevalence of N. mikurensis in questing ticks decreased to 8% in 2010. Neoehrlichia mikurensis-positive I. ricinus ticks were found in two out of three regions in Belgium. A fraction of the ticks from the N. mikurensis-negative area (Brussels) were positive for A. phagocytophilum, which was comparable to other regions (data not shown), indicating that the processing and testing of ticks from this area was not affecting the outcome of the results. The results for the A. phagocytophilum will be published elsewhere. To determine whether N. mikurensis is present in the UK, 338 I. ricinus and 63 D. reticularis ticks from a previous study were tested [27]. These ticks were collected at 7 dispersed study areas in the UK and were partially caught by blanket dragging and removed from wildlife, pets and humans. Anaplasma phagocytophilum, but not N. mikurensis, was detected in these tick lysates.

Role of ticks in the transmission of N. mikurensis

Transovarial (vertical) transmission has been implicated for Rickettsia [33] and Anaplasma [34], but not for Ehrlichia species [35]. Whether N. mikurensis is transmitted transovarially in I. ricinus has not been investigated so far. The prevalence of N. mikurensis was determined in 55 pools of 5 questing I. ricinus larvae from Vrouwenpolder, where nymphal and adult ticks were found to be positive for N. mikurensis (Table 4). None of the 55 pools were N. mikurensis- positive (Table 5). Some of the pools were positive for A. phagocytophilum, approving the used methodology. The prevalence of N. mikurensis in questing I. ricinus nymphs was ~7%, whereas the prevalence in adult ticks was ~ 11% (Table 5). No significant differences were observed in the prevalence between questing male and female I. ricinus ticks. To investigate the role of other tick species in the transmission of N. mikurensis: Dermacentor reticulatus I. hexagonus and I. arboricola were analysed for the presence of N. mikurensis (in the multiplex real-time PCR). None were found positive (Table 6). Again, some were found positive for the A. phagocytophilum msp2 gene (data not shown), indicating that there is no significant inhibition within these samples.

Potential reservoir hosts of N. mikurensis

To investigate the possible mammalian hosts for N. mikurensis, 79 spleen samples of different wild small mammals were tested by (nested)-PCR for the presence of gltA and GroEL (Table 7). PCR-positive samples were sequenced to confirm the presence of N. mikurensis. Both the GroEL and gltA sequences isolated from spleen were identical to the N. mikurensis sequences found in the questing ticks in the Netherlands (Figure 1). Spleen samples from Apodemus sylvaticus, Microtus arvalis and Myodes glareolus were N. mikurensis-positive. After the spleen was found positive, other organs (kidney, liver and brain) were also tested for N. mikurensis. All the tested organs were positive.

Whether other mammals in the Netherlands are reservoir hosts is difficult to address, due to the protective status of these animals. An animal can be considered a potential reservoir host when the prevalence of N. mikurensis in ticks feeding on this animal is significantly higher than the prevalence in questing ticks. This is for example the case for Anaplasma phagocytophilum[36–40]. I. ricinus feeding on red deer (Cervus elaphus), European mouflon (Ovis orientalis musimon), wild boar (Sus scrofa) and sheep (Ovis aries) were tested by multiplex real-time PCR. The prevalence of N. mikurensis in feeding ticks was comparable to the prevalence in questing ticks (Table 8).

Discussion

Recently, six human and one canine case of N. mikurensis infection were reported in different locations in Europe. These reports advocate a re-assessment of the occurrence of this microorganism in questing ticks. Schouls and colleagues described an Ehrlichia-like organism (Ehrlichia schotti) in Dutch ticks [8]. In our study, the three genetic markers 16S rDNA, gltA and GroEL of Ehrlichia schotti-positive field isolates turned out to be similar and identical to DNA sequences available from N. mikurensis. Thus, Ehrlichia schotti and N. mikurensis are most likely one and the same species. Previous findings on E. schotti can be interpreted as findings on N. mikurensis. Thus, N. mikurensis has already been present in the Netherlands in 1999 [25, 41]. Furthermore, 11% of 289 engorged I. ricinus removed from humans were N. mikurensis- positive, indicating that the Dutch population is being exposed to ticks infected with N. mikurensis[42]. Remarkably, human and animal cases of N. mikurensis infection in the Netherlands have not yet been described.

The development of a Q-PCR specific for N. mikurensis allowed us to test significant numbers of ticks without having to perform the labour-intensive Reverse-Line blotting. These analyses showed that the N. mikurensis is present in vegetation ticks throughout the Netherlands and Belgium. No N. mikurensis-positive ticks were found in one location in Belgium. One possible explanation is that this location in the Brussels-area is exceptional due to its reduced fauna and flora caused by human interference. This forest in the Brussels-area is also highly fragmented because of a railroad and several major motorways that run through the forest. Several parts of it can be ecologically considered ‘islands’, which could -through isolation of mammal and tick populations- explain the absence of the pathogen in this forest. More ticks of this unique area need to be tested in order to address this hypothesis. Neoehrlichia mikurensis was also not detected in ticks from the UK. This could indicate that these species have not (yet) been established on this island.

The overall prevalence of N. mikurensis in questing nymphs and adults is approximately 7%. From the public health point of view, it indicates that a significant proportion of people contracting a tick bite are exposed to N. mikurensis. Transmission of the N. mikurensis in ticks appears to occur horizontally rather than vertically. None of the tested larvae were found positive, even though the prevalence of nymphs is approximately 7% and 11% for adults. Other tick species, with more restricted host preference than I. ricinus, were also tested for the presence of N. mikurensis. Dermacentor reticulatus, I. hexagonus and questing I. arboricola were found negative. The data indicate that these tick species probably play insignificant roles in the transmission of N. mikurensis. In contrast, I. ricinus can be considered as its main vector in the Netherlands and Belgium.

A potential group of reservoir hosts for N. mikurensis are wild rodents. Indeed, spleen samples and other organs (kidney, liver and brain) of some rodent species turned out to be N. mikurensis-positive, which indicates a systemic infection of these rodents with N. mikurensis. The N. mikurensis isolates from ticks and wild rodents (Table 7) were genetically identical, indicating that rodents are potential reservoir hosts [43]. However, the reservoir potential of rodents can only be by xenodiagnosis or experimental infection. The prevalence of N. mikurensis in I. ricinus ticks feeding on red deer, European mouflon, wild boar and sheep were comparable to the prevalence in questing ticks. From these prevalence data, it was not possible to infer the role of these animals in the transmission of N. mikurensis. However, it is clear that these animals are being exposed to the N. mikurensis through tick bites. Further experiments are necessary to determine whether there are other mammalian reservoirs than wild rodents.

Conclusions

Although human infection of the N. mikurensis has not been reported in the Netherlands, it is unclear to what extent N. mikurensis poses risks to public health. The symptoms described in all of the N. mikurensis infection cases were generally non-specific and usually seen in any other ordinary inflammatory reaction. What’s more, most of the Ehrlichia infections are known to be either asymptomatic or mild, self-limiting diseases [3]. In other words, infection can occur without causing disease. So far, diagnosis has relied only on PCR amplification of the N. mikurensis. The lack of serological tests makes diagnosis particularly difficult. Against these backdrops, the actual incidence of human infection with Ehrlichia is likely to be much higher than currently reported in Europe. Thorough surveillance and improvement of diagnostic tools will probably increase the number of identified human cases, and consequently provide more insight in the public health relevance of N. mikurensis.

References

Hubalek Z: Epidemiology of lyme borreliosis. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2009, 37: 31-50.

Heyman P, Cochez C, Hofhuis A, van der Giessen J, Sprong H, Porter SR, Losson B, Saegerman C, Donoso-Mantke O, Niedrig M: A clear and present danger: tick-borne diseases in Europe. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010, 8 (1): 33-50. 10.1586/eri.09.118.

Ismail N, Bloch KC, McBride JW: Human ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis. Clin Lab Med. 2010, 30 (1): 261-292. 10.1016/j.cll.2009.10.004.

Hofhuis A, van der Giessen JW, Borgsteede FH, Wielinga PR, Notermans DW, van Pelt W: Lyme borreliosis in the Netherlands: strong increase in GP consultations and hospital admissions in past 10 years. Euro Surveill. 2006, 11 (6): E060622 060622-

van Dobbenburgh A, van Dam AP, Fikrig E: Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in western Europe. N Engl J Med. 1999, 340 (15): 1214-1216.

Groen J, Koraka P, Nur YA, Avsic-Zupanc T, Goessens WH, Ott A, Osterhaus AD: Serologic evidence of ehrlichiosis among humans and wild animals in The Netherlands. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002, 21 (1): 46-49. 10.1007/s10096-001-0659-z.

Kawahara M, Rikihisa Y, Isogai E, Takahashi M, Misumi H, Suto C, Shibata S, Zhang C, Tsuji M: Ultrastructure and phylogenetic analysis of 'Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis' in the family Anaplasmataceae, isolated from wild rats and found in Ixodes ovatus ticks. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004, 54 (Pt 5): 1837-1843.

Schouls LM, Van De Pol I, Rijpkema SG, Schot CS: Detection and identification of Ehrlichia, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, and Bartonella species in Dutch Ixodes ricinus ticks. J Clin Microbiol. 1999, 37 (7): 2215-2222.

Brouqui P, Sanogo YO, Caruso G, Merola F, Raoult D: Candidatus Ehrlichia walkerii: a new Ehrlichia detected in Ixodes ricinus tick collected from asymptomatic humans in Northern Italy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003, 990: 134-140. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07352.x.

de Greeff SC, de Melker HE, Schouls LM, Spanjaard L, van Deuren M: Pre-admission clinical course of meningococcal disease and opportunities for the earlier start of appropriate intervention: a prospective epidemiological study on 752 patients in the Netherlands, 2003–2005. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008, 27 (10): 985-992. 10.1007/s10096-008-0535-1.

Beninati T, Piccolo G, Rizzoli A, Genchi C, Bandi C: Anaplasmataceae in wild rodents and roe deer from Trento Province (northern Italy). Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006, 25 (10): 677-678. 10.1007/s10096-006-0196-x.

Pan H, Liu S, Ma Y, Tong S, Sun Y: Ehrlichia-like organism gene found in small mammals in the suburban district of Guangzhou of China. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003, 990: 107-111. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07346.x.

Shpynov S, Fournier PE, Rudakov N, Tarasevich I, Raoult D: Detection of members of the genera Rickettsia, Anaplasma, and Ehrlichia in ticks collected in the Asiatic part of Russia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006, 1078: 378-383. 10.1196/annals.1374.075.

Dugan VG, Gaydos JK, Stallknecht DE, Little SE, Beall AD, Mead DG, Hurd CC, Davidson WR: Detection of Ehrlichia spp. in raccoons (Procyon lotor) from Georgia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2005, 5 (2)): 162-171.

Alekseev AN, Dubinina HV, Van De Pol I, Schouls LM: Identification of Ehrlichia spp. and Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes ticks in the Baltic regions of Russia. J Clin Microbiol. 2001, 39 (6)): 2237-2242.

von Loewenich FD, Baumgarten BU, Schroppel K, Geissdorfer W, Rollinghoff M, Bogdan C: High diversity of ankA sequences of Anaplasma phagocytophilum among Ixodes ricinus ticks in Germany. J Clin Microbiol. 2003, 41 (11): 5033-5040. 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5033-5040.2003.

Welinder-Olsson C, Kjellin E, Vaht K, Jacobsson S, Wenneras C: First case of human "Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis" infection in a febrile patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Microbiol. 2010, 48 (5): 1956-1959. 10.1128/JCM.02423-09.

von Loewenich FD, Geissdorfer W, Disque C, Matten J, Schett G, Sakka SG, Bogdan C: Detection of "Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis" in two patients with severe febrile illnesses: evidence for a European sequence variant. J Clin Microbiol. 2010, 48 (7): 2630-2635. 10.1128/JCM.00588-10.

Diniz PP, Schulz BS, Hartmann K, Breitschwerdt EB: "Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis" infection in a dog from Germany. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49 (5): 2059-2062. 10.1128/JCM.02327-10.

Fehr JS, Bloemberg GV, Ritter C, Hombach M, Luscher TF, Weber R, Keller PM: Septicemia caused by tick-borne bacterial pathogen Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010, 16 (7): 1127-1129.

Pekova S, Vydra J, Kabickova H, Frankova S, Haugvicova R, Mazal O, Cmejla R, Hardekopf DW, Jancuskova T, Kozak T: Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis infection identified in 2 hematooncologic patients: benefit of molecular techniques for rare pathogen detection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011, 69 (3): 266-270. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.10.004.

Tijsse-Klasen E, Fonville M, Gassner F, Nijhof AM, Hovius EK, Jongejan F, Takken W, Reimerink JR, Overgaauw PA, Sprong H: Absence of zoonotic Bartonella species in questing ticks: First detection of Bartonella clarridgeiae and Rickettsia felis in cat fleas in the Netherlands. Parasit Vectors. 2011, 4 (1): 61-10.1186/1756-3305-4-61.

Hillyard P: Ticks of North West Europe. Synopses of the British Fauna. 1996, 52:

Black WCt, Piesman J: Phylogeny of hard- and soft-tick taxa (Acari: Ixodida) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994, 91 (21)): 10034-10038.

Wielinga PR, Gaasenbeek C, Fonville M, de Boer A, de Vries A, Dimmers W, Akkerhuis Op Jagers G, Schouls LM, Borgsteede F, van der Giessen JW: Longitudinal analysis of tick densities and Borrelia, Anaplasma, and Ehrlichia infections of Ixodes ricinus ticks in different habitat areas in The Netherlands. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006, 72 (12)): 7594-7601.

Courtney JW, Kostelnik LM, Zeidner NS, Massung RF: Multiplex real-time PCR for detection of anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42 (7): 3164-3168. 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3164-3168.2004.

Tijsse-Klasen E, Jameson LJ, Fonville M, Leach S, Sprong H, Medlock JM: First detection of spotted fever group rickettsiae in Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus ticks in the UK. Epidemiol Infect. 2011, 139 (4): 524-529. 10.1017/S0950268810002608.

Sanogo YO, Parola P, Shpynov S, Camicas JL, Brouqui P, Caruso G, Raoult D: Genetic diversity of bacterial agents detected in ticks removed from asymptomatic patients in northeastern Italy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003, 990: 182-190. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07360.x.

Naitou H, Kawaguchi D, Nishimura Y, Inayoshi M, Kawamori F, Masuzawa T, Hiroi M, Kurashige H, Kawabata H, Fujita H: Molecular identification of Ehrlichia species and 'Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis' from ticks and wild rodents in Shizuoka and Nagano Prefectures, Japan. Microbiol Immunol. 2006, 50 (1): 45-51.

Rar VA, Livanova NN, Panov VV, Doroschenko EK, Pukhovskaya NM, Vysochina NP, Ivanov LI: Genetic diversity of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia in the Asian part of Russia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2010, 1 (1): 57-65. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2010.01.002.

Yabsley MJ, Murphy SM, Luttrell MP, Wilcox BR, Howerth EW, Munderloh UG: Characterization of 'Candidatus Neoehrlichia lotoris' (family Anaplasmataceae) from raccoons (Procyon lotor). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008, 58 (Pt 12): 2794-2798.

Spitalska E, Boldis V, Kostanova Z, Kocianova E, Stefanidesova K: Incidence of various tick-borne microorganisms in rodents and ticks of central Slovakia. Acta Virol. 2008, 52 (3): 175-179.

Sprong H, Wielinga PR, Fonville M, Reusken C, Brandenburg AH, Borgsteede F, Gaasenbeek C, van der Giessen JW: Ixodes ricinus ticks are reservoir hosts for Rickettsia helvetica and potentially carry flea-borne Rickettsia species. Parasit Vectors. 2009, 2 (1): 41-10.1186/1756-3305-2-41.

Baldridge GD, Scoles GA, Burkhardt NY, Schloeder B, Kurtti TJ, Munderloh UG: Transovarial transmission of Francisella-like endosymbionts and Anaplasma phagocytophilum variants in Dermacentor albipictus (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2009, 46 (3): 625-632. 10.1603/033.046.0330.

Long SW, Zhang X, Zhang J, Ruble RP, Teel P, Yu XJ: Evaluation of transovarial transmission and transmissibility of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2003, 40 (6): 1000-1004. 10.1603/0022-2585-40.6.1000.

Bown KJ, Lambin X, Ogden NH, Begon M, Telford G, Woldehiwet Z, Birtles RJ: Delineating Anaplasma phagocytophilum ecotypes in coexisting, discrete enzootic cycles. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009, 15 (12): 1948-1954.

Liz JS, Anderes L, Sumner JW, Massung RF, Gern L, Rutti B, Brossard M: PCR detection of granulocytic ehrlichiae in Ixodes ricinus ticks and wild small mammals in western Switzerland. J Clin Microbiol. 2000, 38 (3): 1002-1007.

Polin H, Hufnagl P, Haunschmid R, Gruber F, Ladurner G: Molecular evidence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in Ixodes ricinus ticks and wild animals in Austria. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42 (5): 2285-2286. 10.1128/JCM.42.5.2285-2286.2004.

Bown KJ, Begon M, Bennett M, Birtles RJ, Burthe S, Lambin X, Telfer S, Woldehiwet Z, Ogden NH: Sympatric Ixodes trianguliceps and Ixodes ricinus ticks feeding on field voles (Microtus agrestis): potential for increased risk of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in the United Kingdom?. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2006, 6 (4): 404-410. 10.1089/vbz.2006.6.404.

Skotarczak B, Rymaszewska A, Wodecka B, Sawczuk M, Adamska M, Maciejewska A: PCR detection of granulocytic Anaplasma and Babesia in Ixodes ricinus ticks and birds in west-central Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2006, 13 (1): 21-23.

Tijsse-Klasen E, Fonville M, Reimerink JH, Spitzen-van Der Sluijs A, Sprong H: Role of sand lizards in the ecology of Lyme and other tick-borne diseases in the Netherlands. Parasit Vectors. 2010, 3: 42-10.1186/1756-3305-3-42.

Tijsse-Klasen E, Jacobs JJ, Swart A, Fonville M, Reimerink JH, Brandenburg AH, van der Giessen JW, Hofhuis A, Sprong H: Small risk of developing symptomatic tick-borne diseases following a tick bite in The Netherlands. Parasit Vectors. 2011, 4: 17-10.1186/1756-3305-4-17.

Andersson M, Raberg L: Wild Rodents and Novel Human Pathogen Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis, Southern Sweden. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011, 17 (9): 1716-1718. 10.3201/eid1709.101058.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the volunteers and co-workers of the Central Veterinary Institute of Wageningen University and Research Centre, particularly Cor Gaasenbeek Fred Borgsteede and Kitty Maassen who have dedicated much time and effort to monthly collections of ticks. We thank Francine Pacillij, Annette Benning and Frans Jacobs for having collected ticks on large herbivores. We are grateful to Ellen Tijsse-Klasen, Joke van der Giessen, Marieke Opsteegh and Ankje de Vries for collecting rodent samples, support and technical assistance. This study was financially supported by the Dutch Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (VWA), Wageningen University and Research Centre and by the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (VWS). Dieter Heylen was supported by a FWO postdoctoral fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CR, EJS, WT, PH, DH, JK and JM organized and participated in the fieldwork for the collection and determination of wildlife samples and ectoparasites. SJ and MF developed the laboratory tests for the simultaneous detection of N. mikurensis and A. phagocytophilum. SJ, MF and MF carried out the laboratory preparation and testing of all the samples. SJ performed the sequencing and sequence analyses. SJ and HS drafted the manuscript and wrote the final version. HS organized and planned the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13071_2011_570_MOESM1_ESM.docx

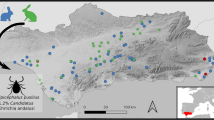

Additional file 1: Figure S1: Geographical distribution of locations (rounds) or global areas (stars) of questing I. ricinus tested positive (red) or negative (green) for N. mikurensis in The Netherlands and Belgium. Exact coordinates of geographical locations are available upon request. (DOCX 8 MB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jahfari, S., Fonville, M., Hengeveld, P. et al. Prevalence of Neoehrlichia mikurensis in ticks and rodents from North-west Europe. Parasites Vectors 5, 74 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-5-74

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-5-74