Abstract

Background

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains expressing D-xylose isomerase (XI) produce some of the highest reported ethanol yields from D-xylose. Unfortunately, most bacterial XIs that have been expressed in S. cerevisiae are either not functional, require additional strain modification, or have low affinity for D-xylose. This study analyzed several XIs from rumen and intestinal microorganisms to identify enzymes with improved properties for engineering S. cerevisiae for D-xylose fermentation.

Results

Four XIs originating from rumen and intestinal bacteria were isolated and expressed in a S. cerevisiae CEN.PK2-1C parental strain primed for D-xylose metabolism by over expression of its native D-xylulokinase. Three of the XIs were functional in S. cerevisiae, based on the strain’s ability to grow in D-xylose medium. The most promising strain, expressing the XI mined from Prevotella ruminicola TC2-24, was further adapted for aerobic and fermentative growth by serial transfers of D-xylose cultures under aerobic, and followed by microaerobic conditions. The evolved strain had a specific growth rate of 0.23 h-1 on D-xylose medium, which is comparable to the best reported results for analogous S. cerevisiae strains including those expressing the Piromyces sp. E2 XI. When used to ferment D-xylose, the adapted strain produced 13.6 g/L ethanol in 91 h with a metabolic yield of 83% of theoretical. From analysis of the P. ruminicola XI, it was determined the enzyme possessed a V max of 0.81 μmole/min/mg protein and a K m of 34 mM.

Conclusion

This study identifies a new xylose isomerase from the rumen bacterium Prevotella ruminicola TC2-24 that has one of the highest affinities and specific activities compared to other bacterial and fungal D-xylose isomerases expressed in yeast. When expressed in S. cerevisiae and used to ferment D-xylose, very high ethanol yield was obtained. This new XI should be a promising resource for constructing other D-xylose fermenting strains, including industrial yeast genetic backgrounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Concern regarding the risks in climate change associated with greenhouse gas emissions is driving policies promoting lower CO2 emissions. In the United States, one third of CO2 emissions are from transportation despite the blending of 14 billion gallons of ethanol originating from grains (e.g. corn) (http://www.ethanolrfa.org accessed Feb. 2013). It is expected that further growth in biofuel production will need to rely on lignocellulosic feedstocks. Lignocellulose includes agricultural and forest wastes as well as dedicated energy crops, such as perennial grasses or tree plantations. Besides being available in larger quantities than grains, these feedstocks do not impinge on the food and feed market, are more CO2 neutral, and will not interfere with current ethanol production.

Several technologies are being developed that use lignocellulose for producing biofuels. The biochemical route is one of the most advanced in terms of development. In this route, carbohydrates are extracted, usually in the form of monosaccharides, and fermented to ethanol. While several efforts are underway at the production scale, there is a continued need for further strain development.

Industrial ethanol is produced using Saccharomyces yeast. Saccharomyces yeasts are favored because of their excellent yield, tolerance of low pH that discourages the growth of spoilage microbes, ability to grow aerobically for efficient cell generation, and robustness. However, plant cell walls contain a mixture of sugars, including D-xylose, which Saccharomyces spp. cannot consume. Over two decades of effort have been expended on developing S. cerevisiae stains that ferment D-xylose and (more recently) L-arabinose and research continues in enhancing the productivity of D-xylose fermentation [1, 2].

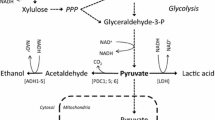

Current research efforts are focused on improving D-xylose transport into the cell, conversion of D-xylose to D-xylulose, and optimization of the non-oxidative pentose phosphate pathway that feeds into glycolysis [3, 4]. Rational strategies have been supplemented by evolutionary adaptation using continuous and serial batch cultures [5–7]. This study focuses on the second area.

Two strategies have been pursued for converting D-xylose to D-xylulose. The earliest effort consisted of expressing two genes from the native D-xylose-fermenting yeast Scheffersomyces stipitis[8, 9]. S. stipitis converts D-xylose to xylitol and xylitol to D-xylulose by the actions of D-xylose reductase and xylitol dehydrogenase. Simple expression of the genes in S. cerevisiae favors production of xylitol over ethanol because the preference of the reductase for NADPH and of the dehydrogenase for NAD+. Additionally, conversion of D-xylulose to D-xylulose-5-phosphate is rate limiting [10]. Redox engineering and fine-tuning D-xylulokinase activity have been successful in reducing xylitol production.

Most bacteria transform D-xylose to D-xylulose in a single step that relies on the enzyme D-xylose isomerase (XI). Efforts to express bacterial D-xylose isomerases in yeast have been largely unsuccessful. A breakthrough occurred when a D-xylose isomerase was discovered in an anaerobic fungus and this D-xylose isomerase was successfully expressed in S. cerevisiae[11, 12]. While initial growth rates were slow, over expressing genes related to D-xylose fermentation and evolutionary adaptation considerably improved its performance. Still this approach is not without its disadvantages stemming from problems related to expression of D-xylose isomerase and the enzyme’s poor kinetic properties. Until recently, the D-xylose isomerase from the anaerobic fungus Piromyces sp. E2 was the only XI gene that functioned in S. cerevisiae. However, due to its low affinity for D-xylose (K m from 20 to 90 mM) [12–14], the search for new D-xylose isomerases that function in S. cerevisiae has continued.

Many of these new XIs do not confer the ability to grow on D-xylose without first modifying the D-xylose isomerase or adapting the host strain. For example, expression of the Clostridium phytofermentans XI in S. cerevisiae was shown in two separate studies to require codon-optimization and strain adaptation [14, 15]. The Ruminococcus flavefaciens XI was recently expressed in S. cerevisiae. Yeast strains expressing several versions of this XI failed to grow aerobically in D-xylose medium, despite one of the expressed XI enzymes having a high specific activity [16]. The XI gene from an anaerobic rumen fungus, Orpinomyces, was also expressed in S. cerevisiae and produced a high specific activity (1.73 U/mg lysate). D-xylose consumption was limited to 10 g/L in 140 hours [17]. However, further strain modification by addition of the sugar transporter SUT1 resulted in 15 g/L D-xylose consumed over the same time period.

The goal of this study was to identify novel D-xylose isomerases that function when expressed in S. cerevisiae. Rumen and intestinal bacteria were used as the source of these additional XIs. The rumen and intestinal microbial ecosystems are promising niches to mine for new XIs due to the prevalence of xylan degrading microorganisms in these environments. A D-xylose isomerase from the rumen bacterium Prevotella ruminicola TC2-24 was discovered that conferred the ability to grow on D-xylose medium when expressed in S. cerevisiae without strain adaption. The strain was further improved by adaptation under aerobic and fermentative conditions. The evolved strain was compared to an adapted S. cerevisiae strain expressing the D-xylose reductase (XR) and xylitol dehydrogenase (XD) genes from Scheffersomyces stipitis.

Results and discussion

Cloning and expression of bacterial D-xylose isomerases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Prevotella spp. and Bacteroides spp. are among the most common xylan-degrading microorganisms isolated from the bovine rumen and human colon, representing a dominant phylum (i.e. Bacteroidetes) in these ecosystems. Bacterial D-xylose isomerases have been reported with much higher affinity for D-xylose when compared to the fungal Piromyces sp. E2 or Orpinomyces D-xylose isomerases. With the goal of identifying D-xylose isomerases with increased affinity for D-xylose, D-xylose isomerase genes from Bacteroides and Prevotella spp. were isolated and expressed in S. cerevisiae. D-xylose isomerase genes were isolated from three Bacteroides spp. (B. uniformis, B. distasonis, and B. ovatus) and P. ruminicola strain TC2-24. Attempts to isolate D-xylose isomerase genes from other P. ruminicola strains failed (see methods). Several Prevotella spp., including the sequenced type strain P. ruminicola 23, have been reported to be missing the gene for D-xylose isomerase. When grown on D-xylose, these strains have detectable but low D-xylose isomerase activity and high D-xylulokinase activity [18, 19]. Yet, they lack an obvious D-xylose reductase and xylitol dehydrogenase pathway. It is unclear whether the absence of a D-xylose isomerase gene is due to an incomplete genome sequence or if they possess an alternate mechanism to convert D-xylose to D-xylulose. P. ruminicola strain TC2-24 shows many similarities with P. ruminicola 23 but does exhibit differences when compared to this type strain [20, 21]. Although we have not investigated further, the presence of a D-xylose isomerase in TC2-24 may be another characteristic of this group of “P. ruminicola 23-like” strains. The D-xylose isomerase identified from P. ruminicola TC2-24 was 439 amino acids long and 79% to 85% identical to D-xylose isomerases from other Prevotella spp. The TC2-24 XI was 79% identical to the Piromyces sp. E2 and Orpinomyces XIs and only 53% identical to the C. phytofermentans XI. The Bacterodies spp. XIs analyzed in this study were 81% to 83% identical to the fungal isomerases.

Aerobic growth in D-xylose medium

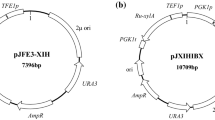

To determine if the D-xylose isomerase genes were functional, each gene was expressed in S. cerevisiae along with the S. cerevisiae D-xylulokinase gene, XKS1, and screened for growth on D-xylose in aerobic liquid culture (Figure 1A). The control strain YRH561, which did not express D-xylose metabolism genes, did not grow. Strain YRH562, expressing the Piromyces sp. E2 XI (and S. cerevisiae XKS1), was included for comparison. YRH562 had a specific growth rate of 0.07 h-1 on D-xylose medium under aerobic growth conditions (Table 1). Several of the bacterial isomerases conveyed the ability for growth on D-xylose at specific growth rates similar to YRH562. As expected, specific activity of a D-xylose isomerase in the S. cerevisiae strain was correlated with the growth of that strain on D-xylose (data not shown). For example, the Bacteroides ovatus XI expressed in strain YRH565 had very low activity and this strain also grew poorly in D-xylose medium (Figure 1A). Equilibrium kinetics of the D-xylose isomerase reaction do not favor production of D-xylulose and co-expression with a D-xylulokinase has been recommend by prior studies to help pull D-xylose into the pathway. As evidence, strains not over expressing D-xylulokinase (YRH628 in Figure 1A) grew slower compared to strains expressing elevated levels of D-xylulokinase. Endogenous XK expression in YRH628 allowed for some growth on D-xylose.

Comparison of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains engineered to express various D-xylose isomerase and D-xylulokinase genes. A) Strains were cultured under aerobic conditions using YP medium with 50 g/L D-xylose. Cultures were incubated at 30°C, shaking at 1000 rpm using a BioLector®. Cell density was measured every 30 minutes. Data shown are mean values from experiments performed in triplicate. B) Strains were cultured under microaerobic conditions using YP medium with 50 g/L D-xylose. Cultures were incubated at 30°C using a Bioscreen C™. Cell density was measured every 30 minutes. Data shown are the average values from three biological replicates. The standard deviation for most values was less than 5%. Panel B uses the same legend as in panel A.

Strain YRH587, expressing the XI from Prevotella ruminicola (TC2-24) and ScXKS1 grew as well as strain YRH562 expressing the Piromyces XI and ScXKS1. Specific growth rates for the two strains were also comparable (Table 1) indicating that the P. ruminicola XI was functional when expressed in S. cerevisiae. Codon optimization of the P. ruminicola XI (YRH629) did not enhance growth relative to YRH587. Additionally, the P. ruminicola D-xylulokinase was substituted for the ScXKS1 gene. YRH631 cells expressing the bacterial XK gene had a similar growth rate as the YRH629 strain expressing the S. cerevisiae XK, indicating that the P. ruminicola XK was also functionally expressed. Strain YRH630, expressing the Piromyces XI gene and the P. ruminicola XK (Figure 1A), grew as well as strain YRH562 expressing the Piromyces XI gene with the S. cerevisiae XK. Cells expressing the B. uniformis XK with the B. uniformis XK reached a higher cell density with the B. uniformis XK compared to the strain expressing the S. cerevisiae XK (YRH592 vs. YRH563). These results demonstrate that the B. uniformis and P. ruminicola XKs are active in S. cerevisiae.

Next, the strains were evaluated for growth under oxygen-limited conditions using the Bioscreen C™, a microtiter based system for measuring microbial growth rates. Aerobic growth studies were performed using a 6-edged flower shaped microtiter plate in the BioLector® under conditions that were optimized for high oxygen transfer rate [22]. Round microtiter plates such as those used in the Bioscreen C™ have been shown to provide lower oxygen transfer rates [22], and decreased oxygen levels are a likely cause of the poor cell growth seen when the Bioscreen C™ is used to culture cells on respiratory carbon sources like ethanol [23]. All of the strains grew poorly when cultured using the Bioscreen C™. The best strains reached a cell density of less than 0.8 OD660 in 96 hours (Figure 1B). Such poor growth under these conditions suggested that adaptation to an oxygen-limited environment would be beneficial.

Adaptation for improved D-xylose fermentation

Adaptation, either by serial batch or continuous cell culture, has been successful for improving growth and fermentation of S. cerevisiae strains expressing different D-xylose isomerase genes [6, 14] as well as for cells expressing the reductase/dehydrogenase genes for D-xylose metabolism [7]. We used serial passage of cells to select for spontaneous changes that resulted in increased growth under fermentative conditions (microaerobic). YRH631 was grown in YPX and transferred weekly for a total of six transfers. Residual D-xylose and the fermentation products ethanol and xylitol were measured for each culture (Figure 2). Steady strain improvement was observed as greater D-xylose utilization and increased production of ethanol (Figure 2). Acetate (not shown) remained constant at 2 g/L.

Adaptation of strain YRH631 to create strain YRH1114. Strain YRH631, expressing the Prevotella ruminicola XI and XK genes was cultured under microaerobic conditions and passaged every seven days. Remaining D-xylose and the fermentation products ethanol and xylitol was measured prior to each passage. Data shown are from one of two replicates.

The adapted strain YRH1114 was isolated from the last serial culture and subsequently evaluated for growth in D-xylose medium under aerobic and microaerobic conditions (Figure 3A, B and Table 1). Strains expressing the Piromyces XI (YRH562) and the unadapted strain expressing the P. ruminicola XI (YRH631) were included for comparison. The adapted strain, YRH1114, showed a significant increase in growth under both culture conditions compare to the unadapted strain. The specific growth rate for YRH1114 was 0.23 h-1, an increase of 3.8-fold compared to the unadapted strain, is among the highest reported growth rates which range from 0.01 h-1 to 0.22 h-1 for a S. cerevisiae strain expressing D-xylose isomerase [6, 13, 14, 16, 17, 24–26].

Growth curves for the adapted Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain engineered to express the P. ruminicola D-xylose isomerase and D-xylulokinase genes. A) Strains were cultured under aerobic conditions in YP medium with 50 g/L D-xylose. Cultures were incubated at 30°C, shaking at 1000 rpm using a BioLector®. Cell density was measured every 30 minutes. Data shown are mean values from experiments performed in triplicate. B) Strains were cultured under microaerobic conditions using YP medium with 50 g/L D-xylose. Cultures were incubated at 30°C using a Bioscreen C™. Cell density was measured every 30 minutes. Data shown are the average values from three biological replicates. The standard deviation for most values was less than 5%. Panel B uses the same legend as in panel A.

D-xylose fermentation

The adapted XI yeast strain (YRH1114) was also evaluated for its ability to ferment D-xylose to ethanol using microaerobic conditions. For comparison, the unadapted yeast strain expressing the P. ruminicola XI and XK was also included in the experiment. Finally, YRH400, a D-xylose fermenting yeast that expresses the alternate D-xylose utilization genes (S. stipitis XR and XD, with elevated ScXKS1) in a commercial yeast background was also included; this strain is currently our best performing strain for D-xylose fermentation [27]. Progress of the fermentations was monitored by measuring production of CO2 (Figure 4): one mole of CO2 is produced for each mole of ethanol. YRH1114 outperformed these strains producing 13.6 g/L ethanol with a metabolic yield of 82.9% of theoretical (Table 2). The unadapated XI yeast strain YRH631 had a much lower ethanol titer (4.1 g/L) even though the metabolic yield was closer to that of the adapted strain YRH1114. The difference in final ethanol concentration between the adapted and unadapted strain arose primarily from differences in D-xylose consumption rate and specific ethanol productivity. The adapted strain had a significantly higher ethanol productivity compared to the unadapted strain also expressing the P. ruminicola XI.

Comparison of D-xylose fermentation using Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains engineered to express the P. ruminicola D-xylose isomerase and D-xylulokinase genes vs. expression of the Scheffersomyces stipitis D-xylose reductase and xylitol dehydrogenase genes. Fermentations were performed using YP medium with 50 g/L D-xylose. Pressure was measured every 15 minutes and converted to mmoles of CO2. Data shown are from a single representative fermentation from experiments performed in triplicate.

The most notable comparison is between the adapted YRH1114 strain and YRH400. Even though YRH400 had likewise been adapted and possessed an industrial yeast background, YRH1114 produced nearly twice as much ethanol (Table 2). This difference is also apparent in lower specific ethanol productivity for YRH400 compared to YRH1114. While YRH400 consumed nearly as much D-xylose, it funneled approximately 50% of the D-xylose to the production of xylitol, which is approximately three times as much as the XI expressing strains. This difference in xylitol production is reflected in the much lower metabolic ethanol yield for YRH400 compared to the other strains. Most strains using the XR/XD pathway suffer from low ethanol yield, although an adapted strain using this pathway was recently reported to have a 79% of theoretical ethanol yield from D-xylose [28].

Selective ethanol production is a hallmark of XI expressing strains because the isomerase step avoids the redox imbalance observed for expression of the genes from S. stipitis. This redox imbalance arises because each enzyme (see introduction) favors an alternative electron carrier. This imbalance has been partially relieved by redox engineering of the XR and XD enzymes [29–32]. Increases in ethanol yield during D-xylose fermentation are seen for some redox engineered strains, but ethanol yields from D-xylose for these strains are still 10% to 19% lower than the yield obtained with the adapted strain described in this study. Thus, the adapted strain expressing the P. ruminicola XI and XK compares favorably to results reported for other strains when cultured on D-xylose. It is also likely the performance of the P. ruminicola XI can be further improved by expressing the gene in a more robust yeast strain such as D5A, which was used for constructing YRH400 [27].

Kinetic parameters

As discussed previously, one concern with XI-based systems is poor affinity of the enzyme for D-xylose. S. cerevisiae does not possess a native D-xylose transporter and intracellular D-xylose concentrations might be rate limiting. Therefore, it was of interest to measure the Michaelis-Menten kinetic constants for the P. ruminicola XI in comparison to other D-xylose isomerases. Enzyme kinetic parameters for the P. ruminicola XI were measured for the pre and post adapted strains.

The K m for the P. ruminicola XI was 40 mM and 34 mM before and after adaptation, respectively. While the K m measurement using lysate from the adapted strain was slightly lower, this difference was not statistically significant. The K m for the P. ruminicola XI appears to be more favorable than the K m for Piromyces sp. E2 XI, which was observed to be 51 mM in this study and varies considerably in the literature (Table 3). Thus, compared to bacterial XIs expressed in yeast, and to most reported K m values for the Piromyces XI, the P. ruminicola XI has a higher affinity for D-xylose.

The measured V max for the unadapted strain was 0.28 μmole/min/mg protein (Table 3) and was not significantly different from Piromyces sp. E2 XI, which was measured at 0.25 μmole/min/mg protein when expressed in our strain. Prior studies have reported V max for the Piromyces XI at 0.05 μmole/min/mg protein (Table 3). Higher enzyme activity than 0.05 μmole/min/mg for the Piromyces sp E2 XI has been observed, but V max was not reported in these studies [12, 25, 26]. Following strain adaptation, V max for the P. ruminicola XI increased 2.9-fold from 0.28 to 0.81 μmole/min/mg protein. This increase probably reflects a higher XI protein concentration in the cell lysate, either from increased expression or stability.

The increase in XI activity for the adapted strain suggested that the copy number of the XI gene may have increased leading to higher protein expression. Gene amplification is a common mechanism for adaption in S. cerevisiae[33, 34] and has been shown to occur under a wide range of circumstances including evolutionary engineering for increased D-xylose metabolism. For instance, one study reported an increase in XI copy number due to integration of up to 32 copies of the Piromyces sp. E2 XI gene [6]. To determine if the P. ruminicola XI gene had integrated into the genome in our adapted strain, we allowed the strain to lose the plasmid containing the XI gene. The strain lacking the XI plasmid was no longer able to grow on D-xylose medium (data not shown), suggesting that integration of the XI gene into the genome did not occur, at least not at levels high enough to support growth on D-xylose in the absence of the XI expression vector. The plasmid containing the XI gene was also rescued from the adapted strain and sequenced. No mutation was found in the XI open reading frame or the promoter or terminator for the gene, indicating that the causative mutation for increased ability to ferment D-xylose resides in the genome. Consistent with this hypothesis, replacing the XI vector in the adapted strain with the original parent XI vector restored the increased growth rate on D-xylose, similar to the original adapted strain (data not shown) while putting the same vector into the unadapted CEN.PK2-1C parent did not. Further analysis of the genome sequence of the adapted strain compared to the parent should reveal the genomic changes responsible for increased D-xylose fermentation.

Conclusions

Three D-xylose isomerases originating from rumen and gastrointestinal tract bacteria were successfully expressed in a S. cerevisiae strain, as judged by growth in aerobic D-xylose cultures. The most promising strain, expressing the XI originating from the rumen bacterium P. ruminicola TC2-24, was adapted in serial batch cultures. The evolved yeast strain (YRH1114) had a specific growth rate of 0.23 h-1 on D-xylose in aerobic culture. In fermentative cultures, it produced 13.6 g/L ethanol in 91 h (0.041 g/gCDW/h) with a metabolic yield of 83%. The P. ruminicola XI had a V max of 0.81 μmole/min/mg protein and a K m of 34 mM for D-xylose.

Methods

Strains, media, and general methods

Escherichia coli strains DH10B, TOP10 (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA, USA), NEB5a, and NEB10b (New England Biolabs (NEB); Ipswich, MA, USA) were used for routine maintenance and preparation of plasmids and were grown in LB medium [35]. Microorganisms and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 4 and Table 5. DNA was transformed into yeast cells using a standard lithium acetate method [36]. Synthetic complete (SC) medium consisted of 6.7 g/L Difco yeast nitrogen base (YNB) (United States Biological; Marblehead, MA, USA), and was supplemented with amino acids as necessary [37]. SC medium was filter sterilized. YP medium (10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L bacto-peptone) was autoclaved without carbohydrate. Sterile D-glucose or D-xylose was added separately.

Cloning of D-xylose isomerase genes for expression in S. cerevisiae

Bacteroides and Prevotella strains were obtained from our in house collection (M. Cotta, USDA-ARS, NCAUR, Peoria, IL, USA) and were cultivated anaerobically as described previously [38]. D-xylose isomerase genes from Bacteroides spp. were PCR amplified from genomic DNA using primers pairs #312/313, #312/314, and #315/316 for strains V923, V975, and V601 respectively (Table 6). DNA fragments corresponding to the expected size for a D-xylose isomerase gene were removed from the agarose gel, purified, and ligated into pCR2.1 TOPO for sequencing. Each of the DNA fragments isolated from the Bacteroides spp. PCR reactions encoded a D-xylose isomerase gene. Each XI gene was cloned into the expression vector pRH167 using Spe I and Sal I restriction endonuclease sites added to the end of the primer used for amplification.

Since a gene for D-xylose isomerase had not been found in P. ruminicola, degenerate primers #243 and #244 were used to amplify an isomerase gene from P. ruminicola strains. Primer #243 was 32-fold degenerate and #244 was 64-fold degenerate. These primers were designed based on Bacteroides spp., and Piromyces sp. E2. Using these primers and a touch-down PCR cycle, we were unable to successfully amplify a D-xylose isomerase gene from any of the P. ruminicola strains tested. A DNA fragment containing a D-xylose isomerase gene was isolated when primers based on the XI from sequence from Prevotella bergensis (accession # ACKS01000045.1) were used (#310 and #311). The only P. ruminicola strain to yield a D-xylose isomerase gene by PCR amplification was strain TC2-24. The P. ruminicola gene from TC2-24 (accession # KC847096) was cloned into pRH167 to create pRH367 for expression of the unoptimized gene in S. cerevisiae.

Codon-optimized genes were obtained from DNA2.0 (Menlo Park, CA,USA) and cloned into vectors for expression in S. cerevisiae. The optimized P. ruminicola (TC2-24) D-xylose isomerase gene was cloned into the high-copy vector pRH167 using the restriction endonucleases Spe I and Sal I, creating pRH384. To create pRH385 the optimized P. ruminicola (T23) D-xylulokinase was cloned into the low-copy vector pRH164 using the same restriction endonucleases. Each vector contained the truncated HXT7 promoter for constitutive expression of the heterologous gene.

Aerobic growth kinetics

Yeast pre-cultures were grown to mid-log phase in synthetic complete medium with 20 g/L D-glucose and washed with sterile water prior to inoculation. YP medium supplemented with 50 g/L D-xylose (YP5X) was used to determine each yeast strain’s ability to assimilate D-xylose aerobically. Cultures were started using 6-edged flower shaped microtiter plates in 800 μl of YP5X at an OD660 of 0.05 and incubated at 30°C, mixing at 1000 rpm using a BioLector® (m2p-labs; Baesweiler, Germany). The BioLector® measures cell density by scattered light, which was measured every 30 minutes. A gain of 20 was used for the experiments to avoid saturation at high optical densities. At this gain, scattered light units were linearly proportional to OD660. Scattered light units were converted to optical density using the conversion factor (OD660 = background subtracted scattered light unit/22.93). Data shown represent the mean values from experiments that were repeated in triplicate. Standard deviation values were less than 10% of the mean. Specific growth rates for each replicate were determined by linear regression of the natural log transformed data (i.e. background subtracted scattered light units) vs. time. The slope of the fitted line during exponential growth was used as the specific growth rate μ (h-1).

Cell culture using the Bioscreen C™ automated microbiology growth curve analysis system (Growth Curves USA; Piscataway, NJ, USA) was performed using 100 well honeycomb plates. Microtiter plates for the Bioscreen C™ have a round geometry unlike the flower-shaped plates used in the BioLector®. Plates were shaken with a high amplitude setting and normal speed setting for 30 seconds with an interval of 60 seconds. OD660 was determined by converting the wideband OD values from the Bioscreen C™ using the equation (OD660 = 1.74OD + 0.535(OD)2 - 0.749(OD)3 + 0.675(OD)4, R2 = 0.999). Data shown represent the mean values from triplicate experiments.

Strain adaptation

Strain adaptation to aerobic conditions was achieved by serial passage of cells in YP medium supplemented with 50 g/L of D-xylose as the only energy source. Serial passage under aerobic conditions was continued for eight weeks. Strain adaptation for D-xylose fermentation was then performed in duplicate by weekly transfer of cells grown under fermentative conditions (microaerobic) for six weeks. During adaptation to fermentative conditions cultures were sampled at each passage and analyzed for optical density, residual D-xylose, and fermentation products (ethanol, glycerol, xylitol, and acetate).

Enzyme assays

Total protein from clarified cell lysates was prepared from mid-log phase cells grown in synthetic complete medium using D-glucose as the carbon source. Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed once with sterile ice-cold water, and centrifuged again. Cell pellets were stored at −80°C for later use. Cells were resuspended in an appropriate amount of Y-PER reagent (Pierce; Rockford, IL, USA) plus protease inhibitors (Complete, mini, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail, Roche; Indianapolis, IN, USA) and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein concentrations were determined with the Quick Start Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, USA) against a bovine serum albumin standard.

D-xylose isomerase activity was assayed essentially as described in [12]. XI assays were performed using buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.15 mM NADH, 2 U sorbitol dehydrogenase (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), and an appropriate amount of cell lysate. Reactions were started by the addition of D-xylose (Sigma; St. Louis, MO, USA) to a final concentration of 500 mM and reactions monitored at 340 nm using a Cary 50 Bio UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Varian; Palo Alto, CA, USA). Specific activity (μmole/min/mg lysate) was determined using the molar absorption coefficient, ϵ340, of 6.22 mM-1 cm-1 for NADH. To ensure that the sorbitol dehydrogenase coupling enzyme was not saturated, the ratio of sorbitol dehydrogenase activity to D-xylose isomerase activity was maintained at > 20 for the assay. Additionally, specific activities reported were proportional to the amount of lysate added in a dilution series. Kinetic parameters were determined by varying the D-xylose concentration from 5 to 500 mM. Each assay was done using lysates prepared from three independent cultures.

Batch fermentation

D-xylose fermentation was investigated by inoculating 100-ml YP cultures with 50 g/L D-xylose at a starting OD660 of 2.0. CO2 production was monitored continuously over the course of the fermentation using a wireless gas production measurement system (Ankom Technologies; Macedon, NY, USA). The wireless system monitors gas production indirectly by measuring cumulative gas pressure; CO2 production is calculated using the ideal gas law. The system was set to vent when the overhead pressure achieved 1 psi and to monitor the accumulated pressure every 15 min. Exponentially growing cells were used for the inoculum. Post fermentation samples were used to determine cell biomass (by OD660), residual sugars, and fermentation products (by high-performance liquid chromatography, HPLC). All fermentation experiments were performed three to four times. Accumulative pressure values were used to calculate the amount of CO2 produced during the fermentation. Carbon recoveries were determined using HPLC data. Carbon recovery calculations were based on total input carbon from D-xylose and measured (HPLC) remaining D-xylose, along with fermentation products. CO2 amounts used for carbon recovery calculations assumed 1 mole of CO2 is produced for every 1 mole of ethanol. Specific ethanol productivity (g ethanol/g cell dry weight/h) was determined using the final OD660 measurement (91 hours) for each batch fermentation. Cell dry weight (CDW) was calculated using an OD-to-CDW conversion factor for the yeast strain CEN.PK2-1C (CDW = 0.58 g/L/OD). The conversion factor was determined by drying cells at differing OD to constant weight at 100°C. Cells were washed three times with distilled water prior to drying to remove trace amounts of medium. OD was measured using a GeneSys 10 vis spectrophotomerer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; Waltham, MA, USA).

Analytical methods

Extracellular metabolites were measured using HPLC as previously described [27]. Samples were analyzed using a SpectraSYSTEM liquid chromatography system (Thermo Electron Corporation, CA, USA) equipped with an automatic sampler, column heater, isocratic pump, refractive index detector, and computer based integrator running Chromquest ver. 2.5 software (Thermo Electron Corporation). Samples were injected (20 μl) onto a sugar column (Aminex HPX-87H Column, 300 x 7.8 mm, Bio Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and eluted with 5 mM sulfuric acid at 0.6 ml/min and 65°C.

Statistical analyses

For experiments with three or greater biological replicates, probability analyses were performed using the Student’s t-test with a two-tailed distribution and compared to the appropriate control strain. Values with p < 0.05 were considered significant for this study. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel.

Abbreviations

- XI:

-

D-xylose isomerase

- XK:

-

D-xylulokinase

- XR:

-

D-xylose reductase

- XD:

-

xylitol dehydrogenase

- OD:

-

optical density

- HPLC:

-

High performance liquid chromatography

References

Bettiga M, Bengtsson O, Hahn-Hägerdal B, Gorwa-Grauslund MF: Arabinose and xylose fermentation by recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing a fungal pentose utilization pathway. Microb Cell Fact 2009, 8: 40. 10.1186/1475-2859-8-40

Bera AK, Sedlak M, Khan A, Ho NWY: Establishment of l-arabinose fermentation in glucose/xylose co-fermenting recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae 424A(LNH-ST) by genetic engineering. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2010, 87: 1803-1811. 10.1007/s00253-010-2609-0

Van-Vleet JH, Jeffries TW: Yeast metabolic engineering for hemicellulosic ethanol production. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2009, 20: 300-306. 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.06.001

Hahn-Hägerdal B, Karhumaa K, Fonseca C, Spencer-Martins I, Gorwa-Grauslund MF: Towards industrial pentose-fermenting yeast strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2007, 74: 937-953. 10.1007/s00253-006-0827-2

Scalcinati G, Otero JM, Van-Vleet JR, Jeffries TW, Olsson L, Nielsen J: Evolutionary engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for efficient aerobic xylose consumption. FEMS Yeast Res 2012, 12: 582-597. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2012.00808.x

Zhou H, Cheng JS, Wang BL, Fink GR, Stephanopoulos G: Xylose isomerase overexpression along with engineering of the pentose phosphate pathway and evolutionary engineering enable rapid xylose utilization and ethanol production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Metab Eng 2012, 14: 611-622. 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.07.011

Sonderegger M, Sauer U: Evolutionary engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for anaerobic growth on xylose. Appl Environ Microb 2003, 69: 1990-1998. 10.1128/AEM.69.4.1990-1998.2003

Jeffries TW, Jin YS: Metabolic engineering for improved fermentation of pentoses by yeasts. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2004, 63: 495-509. 10.1007/s00253-003-1450-0

Ho NWY, Chen Z, Brainard AP: Genetically engineered Saccharomyces yeast capable of effective cofermentation of glucose and xylose. Appl Environ Microb 1998, 64: 1852-1859.

Richard P, Toivari MH, Penttilä M: The role of xylulokinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae xylulose catabolism. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2000, 190: 39-43. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09259.x

Harhangi HR, Akhmanova AS, Emmens R, van der-Drift C, De-Laat WT, Van-Dijken JP, Jetten MS, Pronk JT, Op den Camp HJ: Xylose metabolism in the anaerobic fungus Piromyces sp. strain E2 follows the bacterial pathway. Arch Microbiol 2003, 180: 134-141. 10.1007/s00203-003-0565-0

Kuyper M, Harhangi HR, Stave AK, Winkler AA, Jetten MS, De-Laat WT, Den-Ridder JJ, Op den Camp HJ, van Dijken JP, Pronk JT: High-level functional expression of a fungal xylose isomerase: the key to efficient ethanolic fermentation of xylose by Saccharomyces cerevisiae ? FEMS Yeast Res 2003, 4: 69-78. 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00141-7

Lee SM, Jellison T, Alper HS: Directed evolution of xylose isomerase for improved xylose catabolism and fermentation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Appl Environ Microbiol 2012, 78: 5708-5716. 10.1128/AEM.01419-12

Brat D, Boles E, Wiedemann B: Functional expression of a bacterial xylose isomerase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Appl Environ Microbiol 2009, 75: 2304-2311. 10.1128/AEM.02522-08

Ma M, Liu Z, Moon J: Genetic engineering of inhibitor-tolerant Saccharomyces cerevisiae for improved xylose utilization in ethanol production. BioEnergy Research 2012, 5: 459-469. 10.1007/s12155-011-9176-9

Aeling KA, Salmon KA, Laplaza JM, Li L, Headman JR, Hutagalung AH, Picataggio S: Co-fermentation of xylose and cellobiose by an engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2012, 39: 1597-1604. 10.1007/s10295-012-1169-y

Madhavan A, Tamalampudi S, Ushida K, Kanai D, Katahira S, Srivastava A, Fukuda H, Bisaria VS, Kondo A: Xylose isomerase from polycentric fungus Orpinomyces : gene sequencing, cloning, and expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for bioconversion of xylose to ethanol. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2009, 82: 1067-1078. 10.1007/s00253-008-1794-6

Matte A, Forsberg CW, Gibbins AMV: Enzymes associated with metabolism of xylose and other pentoses by Prevotella ( Bacteroides ) ruminicola strains, Selenomonas ruminantium D, and Fibrobacter succinogenes S85. Can J Microbiol 1992, 38: 370-376. 10.1139/m92-063

Dodd D, Mackie RI, Cann IK: Xylan degradation, a metabolic property shared by rumen and human colonic Bacteroidetes . Mol Microbiol 2011, 79: 292-304. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07473.x

Avgustin G, Wright F, Flint HJ: Genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships among strains of Prevotella ( Bacteroides ) ruminicola from the rumen. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1994, 44: 246-255. 10.1099/00207713-44-2-246

Avgustin G, Wallace RJ, Flint HJ: Phenotypic diversity among ruminal Isolates of Prevotella ruminicola: Proposal of Prevotella brevis sp. nov., Prevotella byantii sp. nov., and Prevotella albensis sp. nov. and redefinition of Prevotella ruminicola. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997, 47: 284-288. 10.1099/00207713-47-2-284

Funke M, Diederichs S, Kensy F, Müller C, Büchs J: The baffled microtiter plate: Increased oxygen transfer and improved online monitoring in small scale fermentations. Biotechnol Bioeng 2009, 103: 1118-1128. 10.1002/bit.22341

Warringer J, Blomberg A: Automated screening in environmental arrays allows analysis of quantitative phenotypic profiles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Yeast 2003, 20: 53-67. 10.1002/yea.931

Kuyper M, Hartog MM, Toirkens MJ, Almering MJ, Winkler AA, Van-Dijken JP, Pronk JT: Metabolic engineering of a xylose-isomerase-expressing Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain for rapid anaerobic xylose fermentation. FEMS Yeast Res 2005, 5: 399-409. 10.1016/j.femsyr.2004.09.010

Karhumaa K, Garcia Sanchez R, Hahn-Hägerdal B, Gorwa-Grauslund MF: Comparison of the xylose reductase-xylitol dehydrogenase and the xylose isomerase pathways for xylose fermentation by recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb Cell Fact 2007, 6: 5. 10.1186/1475-2859-6-5

Parachin NS, Gorwa-Grauslund MF: Isolation of xylose isomerases by sequence- and function-based screening from a soil metagenomic library. Biotechnol Biofuels 2011, 4: 9. 10.1186/1754-6834-4-9

Hector RE, Dien BS, Cotta MA, Qureshi N: Engineering industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains for xylose fermentation and comparison for switchgrass conversion. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 38: 1193-1202. 10.1007/s10295-010-0896-1

Bera AK, Ho NW, Khan A, Sedlak M: A genetic overhaul of Saccharomyces cerevisiae 424A(LNH-ST) to improve xylose fermentation. J Ind Microbiol Biot 2011, 38: 617-626. 10.1007/s10295-010-0806-6

Jeppsson M, Bengtsson O, Franke K, Lee H, Hahn-Hägerdal B, Gorwa-Grauslund MF: The expression of a Pichia stipitis xylose reductase mutant with higher K m for NADPH increases ethanol production from xylose in recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Biotechnol Bioeng 2006, 93: 665-673. 10.1002/bit.20737

Petschacher B, Nidetzky B: Altering the coenzyme preference of xylose reductase to favor utilization of NADH enhances ethanol yield from xylose in a metabolically engineered strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Microb Cell Fact 2008, 7: 9. 10.1186/1475-2859-7-9

Bengtsson O, Hahn-Hägerdal B, Gorwa-Grauslund MF: Xylose reductase from Pichia stipitis with altered coenzyme preference improves ethanolic xylose fermentation by recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Biotechnol Biofuels 2009, 2: 9. 10.1186/1754-6834-2-9

Krahulec S, Klimacek M, Nidetzky B: Analysis and prediction of the physiological effects of altered coenzyme specificity in xylose reductase and xylitol dehydrogenase during xylose fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J Biotechnol 2012, 158: 192-202. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.08.026

Stambuk BU, Dunn B, Alves SL Jr, Duval EH, Sherlock G: Industrial fuel ethanol yeasts contain adaptive copy number changes in genes involved in vitamin B1 and B6 biosynthesis. Genome Res 2009, 19: 2271-2278. 10.1101/gr.094276.109

Dunham MJ, Badrane H, Ferea T, Adams J, Brown PO, Rosenzweig F, Botstein D: Characteristic genome rearrangements in experimental evolution of Saccharomyces cerevisiae . P Natl Acad Sci USA 2002, 99: 16144-16149. 10.1073/pnas.242624799

Sambrook J, Russell DW: Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3rd edition. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001.

Gietz D, Woods RA: Transformation of yeasts by the lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol 2002, 350: 87-96.

Amberg BC, Burke DJ, Strathern JN: Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual. 2005 edition. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2005.

Whitehead TR, Cotta MA, Collins MD, Falsen E, Lawson PA: Bacteroides coprosuis sp. nov., isolated from swine-manure storage pits. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005, 55: 2515-2518. 10.1099/ijs.0.63869-0

Christianson TW, Sikorski RS, Dante M, Shero JH, Hieter P: Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene 1992, 110: 119-122. 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90454-W

Hector RE, Mertens JA, Bowman MJ, Nichols NN, Cotta MA, Hughes SR: Saccharomyces cerevisiae engineered for xylose metabolism requires gluconeogenesis and the oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway for aerobic xylose assimilation. Yeast 2011, 28: 645-660. 10.1002/yea.1893

Disclaimer

†Mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing scientific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the US Department of Agriculture. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

§This article is a US Government work and is in the public domain in the USA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katherine Card and Patricia O’Bryan for their excellent technical assistance throughout this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

REH, BSD, and MAC are listed on a national pending patent (application number US 13/616,629) for the sequence of the Prevotella ruminicola TC2-24 D-xylose isomerase gene and expression of the XI and P. ruminicola XK for the purpose of D-xylose fermentation.

Authors’ contributions

REH and BSD performed the work presented in this study. REH designed the study and drafted the manuscript. BSD and JAM participated in design of the study and helped draft the manuscript. MAC supervised the work, and assisted in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hector, R.E., Dien, B.S., Cotta, M.A. et al. Growth and fermentation of D-xylose by Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing a novel D-xylose isomerase originating from the bacterium Prevotella ruminicola TC2-24. Biotechnol Biofuels 6, 84 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1754-6834-6-84

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1754-6834-6-84