Abstract

Background

An effective method for obtaining resistant transgenic plants is to induce RNA silencing by expressing virus-derived dsRNA in plants and this method has been successfully implemented for the generation of different plant lines resistant to many plant viruses.

Results

Inverted repeats of the partial Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) movement protein (MP) gene and the partial Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) replication protein (Rep) gene were introduced into the plant expression vector and the recombinant plasmids were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation was carried out and three transgenic tobacco lines (MP16-17-3, MP16-17-29 and MP16-17-58) immune to TMV infection and three transgenic tobacco lines (Rep15-1-1, Rep15-1-7 and Rep15-1-32) immune to CMV infection were obtained. Virus inoculation assays showed that the resistance of these transgenic plants could inherit and keep stable in T4 progeny. The low temperature (15℃) did not influence the resistance of transgenic plants. There was no significant correlation between the resistance and the copy number of the transgene. CMV infection could not break the resistance to TMV in the transgenic tobacco plants expressing TMV hairpin MP RNA.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that transgenic tobacco plants expressed partial TMV movement gene and partial CMV replicase gene in the form of an intermolecular intron-hairpin RNA exhibited complete resistance to TMV or CMV infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The plant disease caused by Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) or Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) is found worldwide. The two viruses are known to infect more than 150 species of herbaceous, dicotyledonous plants including many vegetables, flowers, and weeds. TMV and CMV cause serious losses on several crops including tobacco, tomato, cucumber, pepper and many ornamentals. During the last decade, several laboratories have tried to introduce resistance to TMV or CMV by genetic engineering. Virus resistance in plants containing virus-derived transgene, usually by the expression of functional or dysfunctional coat protein, movement protein or polymerase gene, has been widely reported. The TMV coat protein gene was used in the first demonstration of virus-derived, protein-mediated resistance in transgenic plants [1]. Pathogen-derived resistance for CMV often showed only partial resistance or very narrow spectrum of resistance to the virus [2].

RNA silencing or post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS), developed during plant evolution, functions as a defense mechanism against foreign nucleic acid invasions (viruses, transponsons, transgenes) [3]. Since the phenomenon of RNA silencing was first observed by Napoli [4], research has been carried out to elucidate its mechanism. PTGS is a mechanism closely related to RNA interference, which is involved in plant defense against virus infection [5, 6]. It was found that when a inverted repeated sequences of partial cDNA from a plant virus are introduced into host plants for expression of dsRNA and induction of RNA silencing, the transgenic plants can silence virus corresponding gene and are resistant to virus infection [7, 8]. More than 90% of transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana lines were resistant to the virus when engineered with hairpin constructs using Plum pox virus P1 and Hc-Pro genes sequences under the 35S-cauliflower mosaic virus promoter [9]. For the current study, we expressed the partial TMV movement protein (MP) gene and the partial CMV replication protein (Rep) gene in the form of an intermolecular intron-hairpin RNA in transgenic tobacco. We analyzed the resistance of T0 to T4 transgenic plants. We found that the two T4 transgenic lines with single copy were completely resistant to the corresponding virus, and the viral resistance of transgenic plants did not be affected by the low temperature (15℃).

Results

Transformation and analysis of T0 plants

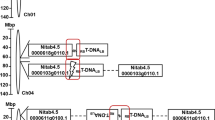

Transgenic tobacco plants expressing hairpin RNA derived from TMV ΔMP or CMV ΔRep gene were generated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (Figure 1). Thirty T0 transgenic plant lines containing TMV MP sequences and twenty T0 transgenic plant lines containing CMV Rep sequences were obtained by kanamycin selection. The specific DNA fragment was amplified in all transgenic lines by PCR using primers TMV MP-F1 and TMV MP-R1 specific for TMV MP or primers ΔRep-F and ΔRep-R specific for CMV Rep gene (data not shown). Southern blot analyses of selected transgenic lines indicated that the MP or Rep gene fragment was integrated into the genomic DNA and the copy number of the foreign gene was estimated to be one to more than five (Table 1).

Resistant response of T0 to T4 transgenic progenies to infection of TMV or CMV

The successive generation seeds were obtained by self-pollination from inoculated plants and the progenies of different lines were gained simultaneously for further analyses. Seedlings per each line were randomly taken from the resultant regenerates for virus inoculation tests. The T1 progenies of T0 parental lines, MP16, MP31, MP39, MP53, Rep15, Rep17, Rep25 and Rep53 contained some plants that were immune and others that were susceptible, whereas the T0 parental line MP36 or Rep727 which was susceptible to the virus yielded only susceptible progenies in successive generations (Table 1). The progeny of T0 lines MP16 and Rep15 was confirmed to a have a segregation ratio of 3:1 (immune: susceptible), suggesting the presence of a single dominant transgene locus in each line, and Southern blot analysis revealed that the loci each appear to have a single transgene (Table 1).

Responses to TMV or CMV infection were further examined for the phenotype of T2, T3 and T4 generation. Resistant T1 lines were randomly selected from each of the six T0 lines (MP16, MP31, MP39, MP53, Rep15 and Rep17) that generated both resistant and susceptible progenies and the two T0 lines (MP36 or Rep727) that only generated susceptible progenies were also selected. In the screening of the T2 generation, plants were randomly selected and inoculated with TMV or CMV. Most of the T2 generation plants derived from resistant T1 lines segregated for both resistant and susceptible phenotype, whereas all T2 progenies from the resistant T1 lines, MP16-17 and Rep15-1, were immune, which showed no any symptoms and no virus replication when measured by TAS-ELISA at 25 days after inoculation (Table 2). The resistant T2 lines MP16-17-3, MP16-17-29, MP16-17-58, Rep15-1-1, Rep15-1-7 and Rep15-1-32 generated only immune phenotypes in the successive T3 and T4 generations, confirming the stable inheritance of resistance (Table 2), although most of the other resistant parental T2 or T3 segregated for a few susceptible plants in T3 or T4 generations. On the contrary, all of the T2 progenies from susceptible T1 lines (MP36-17 or Rep727-1), were susceptible to TMV or CMV and did not segregate for resistance in the successive generations (Table 2). T4 transgenic plants kept immunity phenotypes were shown in Figure 2. The immunity transgenic plants (hp) were completely asymptomatic (Figure 2A and 2B). When samples from inoculated leaves and new emergent leaves of different immune T4 lines were detected with TAS-ELISA at 25 days after CMV or TMV inoculation, the absorbance value from either inoculated or new (systemic) leaves of inoculated plants were as low as negative samples (wt-) (Figure 2C and 2D), which indicated that the virus replication was prevented at local and systemic infection in transgenic immunity plants. Severe mosaic symptoms were found at 30 days after TMV or CMV inoculation on untransformed wild-type plants (wt+) (Figure 2A and 2B). The results suggest that the resistance induced by the hairpin RNA is stably inherited through self-pollination for the fourth generations.

(A, B) Reaction of T 4 transgenic plants (hp) to TMV (A) or CMV (B) infection at three-month after virus inoculation. Wild-type Nicotiana tabacum (cv. Yunyan 87) plants inoculated with buffer (wt-) or with TMV or CMV (wt+) were used as controls. (C, D) Accumulation levels of TMV (C) or CMV (D) in T4 transgenic plants. The 5-6 leaves stage T4 transgenic plants were mechanically inoculated with TMV or CMV and new emergent leaves were collected at 25 days after inoculation for ELISA. The absorbance value represents the mean value obtained from three independent ELISA assays. Plants were considered as virus infected when the corresponding absorbance values measured at 405 nm were more than two times as compared to mean absorbance values from the healthy plants. I, inoculated leaves; N, new growth leaves. wt-, wild type plant inoculated with buffer; wt+, wild type plant inoculated with TMV or CMV.

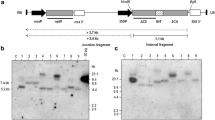

Comparative analysis of the T2 or T4 transgene and the mode of expression in terms of resistance

Correlation between the number of transgene insertions and the type of RNA silencing in tobacco were investigated in this study. Genomic DNA of each line was digested with Dra I, Eco RI or Eco RV (in the genomic DNA outside of the hairpin cDNA). The resistant T1 plants derived from resistant T0 lines (MP16, MP53 or Rep15, Rep17) carried one to two copies of transgenes by Southern blot analyses (data not shown). Then the transgene copy number of the T2 progenies from resistant T1 lines (MP16-17, MP53-52 or Rep 15-1, Rep 17-8) were also detected by Southern blot. The transgene copy number of hybridized DNA restriction fragments varied among the progenies regardless of the infection type. For example, there were immune lines containing one (Figure 3A, MP16-17-29) or two copies of transgene (Figure 3B, Rep17-8-7), but susceptible lines with one (Figure 3A, MP16-17-21) or more than three copies of transgene (Figure 3A, MP53-52-24) were also observed. So no any co-relationships between the transgene copy number and viral resistance level were found. Southern blot analysis results of T4 plants derived from T3 lines (MP16-17-29-9 or Rep15-1-1-15) which contained single copy showed that all T4 plants carried single copy (Figure 3).

Southern blot analyses of T 2 and T 4 transgenic plants expressing hairpin RNA of TMV partial MP (A) or CMV partial Rep (B). Genomic DNA from immune (+), susceptible (-) or wild type tobacco (wt) plants was digested with Dra I, Eco RI or Eco RV, and hybridized with a radioactively labeled TMVΔMP (A) or CMVΔRep (B) probe.

Next, we determined the accumulation of transgene-derived RNA transcripts. Northern hybridization analyses confirmed that only very little transcript of the transgene could be detected at day 25 after the virus inoculation or before virus inoculation, whereas in the wild-type infected plants, the accumulation level of the viral genomic RNA was very high (Figure 4A and 4B).

Northern blot analyses of TMV RNA (A), CMV RNA (B), TMV siRNA (C), or CMV siRNA (D) of T 4 transgenic plants before inoculation (-) or after inoculation with TMV or CMV. Wild type plant (wt) was used as a control. The size of the marker DNA oligomers (24nts) was presented on the left. The lower panel shows the loading level of each RNA sample by ethidium bromide staining.

The virus-specific siRNA was detected by Northern blot analysis of low weight RNAs prepared from the leaves of T4 transgenic and non-transgenic tobacco plants using [α-32P]dCTP-labelled partial MP or Rep gene as a probe and the result showed distinct hybridization signal bands of expected size for siRNA (approximately 21-24 nts, homologous to the MP or Rep transcripts) only existed in immune transgenic plants whether virus was inoculated or not. No siRNA could be detected in healthy wild-type control plants (Figure 4C and 4D).

In our study, all the progenies from MP16-17-29-7, MP16-17-29-7 lines or Rep15-1-1-15, Rep15-1-1-26 lines did not show any symptoms of local or systemic infection during their entire life cycle, and grew normally, developed flowers, and later set fruits with normal seeds. Inoculated non-transgenic control plants showed a significant delay in flowering, stunting and less or no seeds when compared to the un-inoculated control plants. There were no differences in the plant height and seed weight between the inoculated transgenic immune plants and healthy non-transgenic plants (Table 3).

Accumulation and composition of siRNAs at both one and three months after virus inoculation were compared, and results showed that there was little change of siRNAs at both one and three months (Figure 5). 21-24 nts siRNAs were at a high level at one month after virus inoculation, and the level of 21nts siRNA slight decrease but 24 nts siRNA level kept stable at three months after virus inoculation, which was supposed to play a role in systemic silencing and methylation of homologous DNA [10]. Thus, it seemed that the generation of transgene-specific siRNA could keep steady in the whole growth stage of T4 transgenic plants consistent to the resistance of T4 transgenic plants.

Detection of CMV Rep specific siRNA at one or three months after virus inoculation in T 4 transgenic lines Rep 15-1-1-15. 1 and 2 represent two different T4 transgenic plants. wt represents wild plant. I, inoculated leaves; N, new growth leaves. The lower panel shows the loading level of each RNA sample by ethidium bromide staining.

RNA silencing-based virus resistance phenotypes were kept at low temperature

To examine the effect of temperature on the virus resistance, the virus symptoms were observed and the virus RNA and siRNA of T4 progeny plants were detected at 24℃ and 15℃ at 25 days after TMV or CMV inoculation. Virus inoculation test showed that transgenic plants (MP16-17-29-9 or Rep15-1-1-15 lines) were immune to TMV or CMV at both 15℃ and 24℃ (Figure 6A). At 15℃, no any virus symptoms was developed and the virus RNA was low beyond a detected level (Figure 6B), siRNA was accumulated to a level as same as at 24℃ (Figure 6C), demonstrating that the transgene-mediated virus resistance was kept at low temperature.

Symptoms (A), viral RNA (B) and siRNA (C) accumulation levels of the transgenic plants expressing TMV hairpin MP RNA (left) or CMV hairpin Rep RNA (right) at 25 days after virus inoculation at 24℃or 15℃. Transgenic plants (hp) and wild type (wt) plants were infected with TMV or CMV. Ribosomal RNA was applied as loading control.

CMV infection did not break resistance to TMV in transgenic tobacco plants expressing TMV hairpin MP RNA

In order to know whether CMV can suppress the TMV silencing in TMV resistant transgenic plants, we carried out the following experiment. T4 progeny plants expressing TMV hairpin MP RNA were inoculated with TMV or CMV firstly, and then CMV or TMV at 25 days after TMV or CMV inoculation, or doubly inoculated with the two viruses at the same time. The TMV and CMV are subsequently detected by TAS-ELISA and Northern blot. Six weeks after inoculation, mosaic symptoms were observed on the upper leaves of the new emergent leaves of all inoculated transgenic plants, but not on the transgenic plants inoculated with TMV or buffer as controls (data not shown). TAS-ELISA results indicated that all the transgenic plants showing mosaic symptoms were infected by CMV (Table 4). No TMV was detected in inoculated transgenic tobacco plants, but was detected in untransformed tobacco plants. Northern blot analysis confirmed that TMV replicated to high level in all untransformed tobacco control plants, but to undetectable level in transgenic plants when co-inoculation with CMV and TMV (data not shown). The above results indicate that CMV could not break resistance to TMV in transgenic tobacco plants expressing TMV hairpin MP RNA.

Discussion

Numerous examples of pathogen-derived resistance have been reported for a wide range of plant viruses. Transgenic plants expressing viral coat proteins have been successfully conferred the resistance to the corresponding viruses [1, 11, 12]. Expression of sequences corresponding to other viral genes have also become a successful tool for inducing pathogen-derived resistance, such as replicase gene [13–16], protease gene [17, 18] and movement protein gene [19–21]. Transgenic pants expressing dsRNA by introduction of an inverted repeat sequence, spaced by an intron, into plants could reach 90% efficiency of gene silencing [22, 23]. An effective method for obtaining resistant transgenic plants is therefore to induce RNA silencing by expressing virus-derived dsRNA in plants and this method has been successfully implemented for the generation of different plant lines resistant to many viruses [7, 9, 24–30]. We have demonstrated that transgenic tobacco plants expressed partial TMV movement gene or CMV replicase gene in the form of an intermolecular intron-hairpin RNA exhibited complete resistance to TMV or CMV infection. Due to the dsRNA nature, engineered specific RNA molecules were targeted for degradation, so only small steady-state amounts of the actual hairpin transcripts could be expected in the transgenic lines [28, 31, 32]. Our results also showed only very little transcript of the transgene could be detected after or before virus inoculation. Occurrence of siRNA is one of the most important characteristics of RNA silencing and can be a reliable molecular marker that is closely associated with viral resistance in transgenic plants expressing viral genes [31, 33, 34]. We also found siRNAs characteristic to RNA silencing were detected to accumulate in high levels in resistant transgenic plants whether virus was inoculated or not. These results indicated that TMV or CMV resistance observed in the resistant transgenic tobacco plants is attributed to RNA silencing.

Multiple complex patterns of transgene integration have been detected in many species such as tomato [28], cereal [7, 35] and wood perennial tree (Prunus domestica) [36]. No general conclusions can be made as to whether a second copy of the transgene would increase the likelihood of virus resistance [31], so it is suggested no correlation between the copy number of insertions and types of RNA silencing [36, 37]. We also found no correlation between the resistance and the copy number of the transgene.

Kalantidis K et al. [24] reported the concentration of siRNA reached a plateau at 30 days post-germination (one month) and then remained stable in the course of further development (two months). But Missiou et al. [31] reported that the accumulation and composition of transgene-specific siRNA was changed when plants were grown. Our results showed that there was little change of accumulation and composition of siRNAs at both one and three months after virus inoculation.

Plant-virus interactions are strongly modified by environmental factors, especially by temperature. High temperature is frequently associated with attenuated symptoms and with low virus content [38]. But rapid spread of virus disease and development of severe symptoms are frequently associated with low temperature [39]. Studied have shown that low temperature inhibited the accumulation of siRNAs in insect, plant and mammalian cells [10, 40, 41]. At low temperature, RNA silencing induced by virus or transgene was inhibited, which leads to enhancing virus susceptibility, to loss of silencing-mediated transgenic phenotypes and to dramatically reducing the level of siRNA, but the accumulation level of miRNA was not influenced by temperature [10]. So RNA silencing-based transgenic phenotypes were reported to be lost at low temperature (15°C). We found that RNA silencing-based transgenic phenotypes were not lost at low temperature (15°C). The virus siRNAs level was stable at both 24°C and 15°C and no obvious decrease of virus siRNAs accumulation was found at 15°C as compared with that at 24°C. Bonfim et al. [26] reported that the amount of siRNA at 25 °C showed a slight decrease as compared with that at 15 °C compared, but they did not test whether the resistance of transgenic bean plants with an intron-hairpin construction was influent. The differences of low temperature on RNA silencing-based transgenic phenotypes were unknown.

The PTGS pathway can be inhibited by suppressors encode by plant viruses [42, 43]. The 2b protein of CMV suppresses PTGS by directly interfering with the activity of the mobile silencing signal [44, 45]. Guerini and Murphy [46] reported that Capsicum annum cv. Avelar plants resisted systemic infection by the Florida isolate of Pepper mottle potyvirus (PepMoV-FL). However, co-infection of Avelar plants with CMV alleviated this restricted movement, allowing PepMoV-FL to invade young tissues systemically. Our results showed that the TMV-resistant transgenic tobacco plants were clearly not impacted by the suppressor, the 2b protein of CMV.

It's clear that regardless of the mechanistic details, the expression of viral dsRNA seems to be a highly efficient way to engineer virus-resistant plants, and the resistance induced by the hairpin RNA can be stably inherited through self-pollination for the fourth generations. Through this strategy, we can select for the most promising lines that are immune to viruses. Besides the high efficiency for generating transgenic plants resistant to a viral pathogen, the RNA-mediated resistance is good for environmental biosafety over the different protein mediated resistance as potential risks of heterologous encapsidation and recombination of virus are diminished.

Conclusions

We expressed the partial TMV movement protein (MP) gene and the partial CMV replication protein (Rep) gene in the form of an intermolecular intron-hairpin RNA in transgenic tobacco. We analyzed the resistance of T0 to T4 transgenic plants. We found that T4 transgenic lines with single copy were completely resistant to the corresponding virus, and viral resistance of transgenic plants did not be affected by the low temperature (15℃). No significant correlation between the resistance and the copy number of the transgene was found. CMV infection could not break the resistance to TMV in the transgenic tobacco plants expressing TMV hairpin MP RNA.

Methods

Plant material and viruses

Nicotiana tabacum cv. Yunyan 87 was provided by Dr. Liu Yong (Yunnan Institute for Tobacco Science, China). TMV and CMV were isolated by the author's laboratory and maintained on Nicotiana tabacum cv. Xanthi nn in greenhouse.

Construction of plant expression plasmids

Plant expression vector pBIN-TMVΔMP(i/r), which contains inverted repeats of partial TMV MP gene (ΔMP) separated by the soybean intron was constructed previously [47]. For plant expression plasmid containing inverted repeats of CMV partial Rep gene (ΔRep) (Figure 1), specific primersΔRep-F (CGGTCGAC GATAACTAAGTGGTGG, underline was Sal I site) and ΔRep-R (CGATCGAT CCAGACTTCTTGTATTTC, underline was Cla I site) designed according to the published CMV Rep gene (D00355) were used for PCR amplification using the plasmid pFny209 containing CMV Rep gene (kindly provided by professor Jialin Yu, China Agriculture University) and the amplified fragments were inserted into pUCm-T (Shanghai Sango, Shanghai, China) to produce recombinant plasmids pUCm-ΔRep(as) (antisense) and pUCm-ΔRep(s) (sense), respectively. The plasmid pSK-In-ΔRep containing soybean intron and antisense ΔRep fragment was obtained by digesting pUCm-ΔRep(as) with Pst I and Bam HI and inserted into the vector pSK-In (kindly provided by professor Johansen, Danish Plant and Soil Graduate School) between the Pst I and Bam HI site. The plasmid pSK-In-ΔRep was digested by Sal I and Bam HI, and inserted into the Sal I and Bam HI site of the plant expression vector pBIN438 to produce recombinant expression vector pBIN-In-CMVΔRep. The sense ΔRep fragment was obtained by digesting pUCm-ΔRep(s) with Sal I, and then inserted into the Sal I site of pBIN-In-CMVΔRep to produce recombinant plant expression vector pBIN-CMVΔRep(i/r) (Figure 1), containing inverted repeats sequence of CMV ΔRep separated by the soybean intron.

Plant transformation, PCR and Southern blot analysis

The recombinant vector pBIN-TMVΔMP(i/r) or pBIN-CMVΔRep(i/r) was transformed into Agrobacterium tumerfaciens EHA105, respectively, by the tri-parental mating method [48] and transgenic Nicotiana tabacum cv. Yunyan 87 plants were obtained using a leaf disc method as described [47]. Rooted plants were subsequently transferred to soil and grown to maturity in a greenhouse. Following self-fertilization of T0, T1, T2, T3, T4 progenies were tested for antibiotic sensitivity by rooting the seedlings on 50 mg/L of kanamycin. The presence and copy number of integrated intron-hairpin construction in selected tobacco transgenic lines were assessed by PCR and Southern blot. Tobacco genomic DNA was extracted from both the transgenic and non-transgenic leaf tissues (3 g) by the CTAB method [49], and analyzed for the presence of MP or Rep gene by PCR with primers TMV MP-F1 and TMV MP-R1 specific for TMV MP[47] and primers ΔRep-F andΔRep-R specific for CMV Rep. Genomic DNA extracted from the PCR-positive plants (20-30 μg) was completely digested with Dra I or Eco RI or Eco RV, fractionated in 0.8% agarose gels and transferred onto Hybond N+ nylon membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Bucks, UK). DNA was cross-linked to the membrane using an UL-1000 ultraviolet crosslinker (UVP, Upland, CA, USA). Hybridization was conducted as described [50] using the [α-32P]dCTP-labelled TMV MP or CMV Rep gene as probe prepared by random primer procedure according to the Prime-a-Gene Labeling System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

Virus resistance assays

Transgenic plants and wild plants were grown in greenhouse condition for 5 weeks before virus inoculation. Plants were mock-inoculated with phosphate buffer or inoculated with leaves sap extracts [diluted in 0.02 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2)] from plants infected with TMV, CMV or both TMV and CMV (TMV+CMV). The inoculated plants were observed for virus symptoms after virus inoculation.

TAS-ELISA

Leaf tissues (0.1 g) from new emergent leaves of each plant infected with TMV, CMV, TMV+CMV or inoculated with buffer were collected at 15, 25, 45 dpi. The virus concentration in the inoculated plants was detected by triple antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (TAS-ELISA) as described [51]. The absorbance values were measured in a Model 680 Microplate Reader (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA) at 405 nm.

RNA isolation and analysis

Plants tissues were ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen and RNAs were extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Grand Island, N.Y., USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The same RNA extract was separated to high- and low-molecular-mass RNAs using 30% PEG (molecular weight 8000, Sigma, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and 3 M NaCl as described [52]. The high-molecular-mass RNAs (20 μg) from transgenic plant tissues were separated on a 1% formaldehyde agarose gel and transferred to Hybond N+ nylon membranes (Amersham Biosciences) for Northern blot analysis. The low-molecular-mass RNAs (15 μg) were separated on a 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel with 7M urea and transferred to Hybond-N+ nylon membranes (Amersham Biosciences) by electrophoresis transfer at 400 mA for 45 min using a Bio-Rad semidry Trans-Blot apparatus. To verify equal amounts of siRNAs in each lane, gels also were stained with SYBR® Gold nucleic acid gel stain (Invitrogen). Membranes were hybridized as described [50] with [α-32P]dCTP-labelled MP or Rep gene as probe prepared by random primer procedure according to the Prime-a-Gene Labeling System (Promega) overnight at 40℃ in 50% formamide buffer. 10-min three time post-hybridization washes were performed sequentially at 40℃ with 1× sodium chloride-sodium citrate buffer (SSC) supplemented with 0.1% SDS. Hybridization signals were detected by phosphorimaging using a Typhoon 9200 imager (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

References

Abel PP, Nelson RS, De B, Hoffmann N, Rogers SG, Fraley RT, Beachy RN: Delay of disease development in transgenic plants that express the tobacco mosaic virus coat protein gene. Science 1986, 232: 738-743. 10.1126/science.3457472

Beachy RN: Mechanisms and applications of pathogen-derived resistance in transgenic plants. Curr Opin Biotechnol 1997, 8: 215-220. 10.1016/S0958-1669(97)80105-X

Voinnet O: RNA silencing: small RNAs as ubiquitous regulators of gene expression. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2002, 5: 444-451. 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00291-1

Napoli C, Lemieux C, Jorgensen R: Introduction of a chimeric chalcone synthase gene into Petunia results in reversible co-suppression of homologous genes in Trans. Plant Cell 1990, 2: 279-289. 10.1105/tpc.2.4.279

Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC: Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans . Nature 1998, 391: 806-811. 10.1038/35888

Waterhouse PM, Wang MB, Lough T: Gene silencing as an adaptive defence against viruses. Nature 2001, 411: 834-842. 10.1038/35081168

Wang MB, Abbott DC, Waterhouse PM: A single copy of a virus-derived transgene encoding hairpin RNA gives immunity to barley yellow dwarf virus. Mol Plant Pathol 2000, 1: 347-356. 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2000.00038.x

Frizzi A, Huang S: Tapping RNA silencing pathways for plant biotechnology. Plant Biotechnol J 2010, 8: 655-677. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00505.x

Di Nicola-Negri E, Brunetti A, Tavazza M, Ilardi V: Hairpin RNA-mediated silencing of Plum pox virus P1 and HC-Pro genes for efficient and predictable resistance to the virus. Transgenic Res 2005, 14: 989-994. 10.1007/s11248-005-1773-y

Szittya G, Silhavy D, Molnar A, Havelda Z, Lovas A, Lakatos L, Banfalvi Z, Burgyan J: Low temperature inhibits RNA silencing-mediated defence by the control of siRNA generation. EMBO J 2003, 22: 633-640. 10.1093/emboj/cdg74

Palukaitis P, Zaitlin M: Replicase-mediated resistance to plant virus disease. Adv Virus Res 1997, 48: 349-377. full_text

Tepfer M: Risk assessment of virus-resistant transgenic plants. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2002, 40: 467-491. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.120301.093728

Golemboski DB, Lomonossoff GP, Zaitlin M: Plants transformed with a tobacco mosaic virus nonstructural gene sequence are resistant to the virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990, 87: 6311-6315. 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6311

Longstaff M, Brigneti G, Boccard F, Chapman S, Baulcombe D: Extreme resistance to potato virus X infection in plants expressing a modified component of the putative viral replicase. EMBO J 1993, 12: 379-386.

Audy P, Palukaitis P, Slack SA, Zaitlin M: Replicase-mediated resistance to potato virus Y in transgenic tobacco plants. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 1994, 7: 15-22. 10.1094/MPMI-7-0015

Brederode FT, Taschner PE, Posthumus E, Bol JF: Replicase-mediated resistance to alfalfa mosaic virus. Virology 1995, 207: 467-474. 10.1006/viro.1995.1106

Maiti IB, Murphy JF, Shaw JG, Hunt AG: Plants that express a potyvirus proteinase gene are resistant to virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90: 6110-6114. 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6110

Vardi E, Sela I, Edelbaum O, Livneh O, Kuznetsova L, Stram Y: Plants transformed with a cistron of a potato virus Y protease (NIa) are resistant to virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90: 7513-7517. 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7513

Lapidot M, Gafny R, Ding B, Wolf S, Lucas WJ, Beachy RN: A dysfunctional movement protein of tobacco mosaic virus that partially modifies the plasmodesmata and limits virus spread in transgenic plants. Plant J 1993, 4: 959-970. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1993.04060959.x

Malyshenko SI, Kondakova OA, Nazarova Ju V, Kaplan IB, Taliansky ME, Atabekov JG: Reduction of tobacco mosaic virus accumulation in transgenic plants producing non-functional viral transport proteins. J Gen Virol 1993, 74: 1149-1156. 10.1099/0022-1317-74-6-1149

Cooper B, Lapidot M, Heick JA, Dodds JA, Beachy RN: A defective movement protein of TMV in transgenic plants confers resistance to multiple viruses whereas the functional analog increases susceptibility. Virology 1995, 206: 307-313. 10.1016/S0042-6822(95)80046-8

Smith NA, Singh SP, Wang MB, Stoutjesdijk PA, Green AG, Waterhouse PM: Gene expression - total silencing by intron-spliced hairpin RNAs. Nature 2000, 407: 319-320. 10.1038/35036500

Wesley SV, Helliwell CA, Smith NA, Wang MB, Rouse DT, Liu Q, Gooding PS, Singh SP, Abbott D, Stoutjesdijk PA, et al.: Construct design for efficient, effective and high-throughput gene silencing in plants. Plant J 2001, 27: 581-590. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01105.x

Kalantidis K, Psaradakis S, Tabler M, Tsagris M: The occurrence of CMV-specific short RNAs in transgenic tobacco expressing virus-derived double-stranded RNA is indicative of resistance to the virus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 2002, 15: 826-833. 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.8.826

Pandolfini T, Molesini B, Avesani L, Spena A, Polverari A: Expression of self-complementary hairpin RNA under the control of the rolC promoter confers systemic disease resistance to plum pox virus without preventing local infection. BMC Biotechnol 2003, 3: 7. 10.1186/1472-6750-3-7

Bonfim K, Faria JC, Nogueira EO, Mendes EA, Aragao FJ: RNAi-mediated resistance to Bean golden mosaic virus in genetically engineered common bean ( Phaseolus vulgaris ). Mol Plant Microbe Interact 2007, 20: 717-726. 10.1094/MPMI-20-6-0717

Bucher E, Lohuis D, van Poppel PM, Geerts-Dimitriadou C, Goldbach R, Prins M: Multiple virus resistance at a high frequency using a single transgene construct. J Gen Virol 2006, 87: 3697-3701. 10.1099/vir.0.82276-0

Fuentes A, Ramos PL, Fiallo E, Callard D, Sanchez Y, Peral R, Rodriguez R, Pujol M: Intron-hairpin RNA derived from replication associated protein C1 gene confers immunity to tomato yellow leaf curl virus infection in transgenic tomato plants. Transgenic Res 2006, 15: 291-304. 10.1007/s11248-005-5238-0

Krubphachaya P, Juricek M, Kertbundit S: Induction of RNA-mediated resistance to papaya ringspot virus type W. J Biochem Mol Biol 2007, 40: 404-411.

Tyagi H, Rajasubramaniam S, Rajam MV, Dasgupta I: RNA-interference in rice against Rice tungro bacilliform virus results in its decreased accumulation in inoculated rice plants. Transgenic Res 2008, 17: 897-904. 10.1007/s11248-008-9174-7

Missiou A, Kalantidis K, Boutla A, Tzortzakaki S, Tabler M, Tsagris M: Generation of transgenic potato plants highly resistant to potato virus Y (PVY) through RNA silencing. Mol Breeding 2004, 14: 185-197. 10.1023/B:MOLB.0000038006.32812.52

Nomura K, Ohshima K, Anai T, Uekusa H, Kita N: RNA Silencing of the introduced coat protein gene of Turnip mosaic virus confers broad-spectrum resistance in transgenic Arabidopsis . Phytopathol 2004, 94: 730-736. 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.7.730

Hamilton A, Voinnet O, Chappell L, Baulcombe D: Two classes of short interfering RNA in RNA silencing. EMBO J 2002, 21: 4671-4679. 10.1093/emboj/cdf464

Zhang SC, Tian LM, Svircev A, Brown DCW, Sibbald S, Schneider KE, Barszcz ES, Malutan T, Wen R, Sanfacon H: Engineering resistance to Plum pox virus (PPV) through the expression of PPV-specific hairpin RNAs in transgenic plants. Can J Plant Pathol 2006, 28: 263-270. 10.1080/07060660609507295

Yang G, Lee YH, Jiang Y, Kumpatla SP, Hall TC: Organization, not duplication, triggers silencing in a complex transgene locus in rice. Plant Mol Biol 2005, 58: 351-366. 10.1007/s11103-005-5101-y

Hily JM, Ravelonandro M, Damsteegt V, Bassett C, Petri C, Liu Z, Scorza R: Plum pox virus coat protein gene Intron-hairpin-RNA (ihpRNA) constructs provide resistance to plum pox virus in Nicotiana benthamiana and Prunus domestica . J Amer Soc for Hort Sci 2007, 132: 850-858.

Chuang CF, Meyerowitz EM: Specific and heritable genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Arabidopsis thaliana . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000, 97: 4985-4990. 10.1073/pnas.060034297

Hull R: Matthews' Plant Virology. 4th edition. Academic Press: London; 2002.

Harrison BD: Studies on the effect of temperature on virus multiplication in inoculated leaves. Annu Appl Biol 1956, 44: 215-226. 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1956.tb02117.x

Fortier E, Belote JM: Temperature-dependent gene silencing by an expressed inverted repeat in Drosophila . Genesis 2000, 26: 240-244. 10.1002/(SICI)1526-968X(200004)26:4<240::AID-GENE40>3.0.CO;2-P

Kameda T, Ikegami K, Liu Y, Terada K, Sugiyama T: A hypothermic-temperature-sensitive gene silencing by the mammalian RNAi. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004, 315: 599-602. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.097

Carrington JC, Kasschau KD, Johansen LK: Activation and suppression of RNA silencing by plant viruses. Virology 2001, 281: 1-5. 10.1006/viro.2000.0812

Vance V, Vaucheret H: RNA silencing in plants--defense and counterdefense. Science 2001, 292: 2277-2280. 10.1126/science.1061334

Brigneti G, Voinnet O, Li WX, Ji LH, Ding SW, Baulcombe DC: Viral pathogenicity determinants are suppressors of transgene silencing in Nicotiana benthamiana . EMBO J 1998, 17: 6739-6746. 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6739

Guo HS, Ding SW: A viral protein inhibits the long range signaling activity of the gene silencing signal. EMBO J 2002, 21: 398-407. 10.1093/emboj/21.3.398

Guerini MN, Murphy JF: Resistance of Capsicum annuum 'Avelar' to pepper mottle potyvirus and alleviation of this resistance by co-infection with cucumber mosaic cucumovirus are associated with virus movement. J Gen Virol 1999, 80: 2785-2792.

Zhang K, Niu YB, Zhou XP: Transgenic tobacco plants expressed dsRNA can prevent tobacco mosaic virus infection. J Agri Biotechnol 2005, 13: 226-229.

Ditta G, Stanfield S, Corbin D, Helinski DR: Broad host range DNA cloning system for gram-negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1980, 77: 7347-7351. 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7347

Huang C, Xie Y, Zhou X: Efficient virus-induced gene silencing in plants using a modified geminivirus DNA1 component. Plant Biotechnol J 2009, 7: 254-265. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00395.x

Xiong R, Wu J, Zhou Y, Zhou X: Characterization and subcellular localization of an RNA silencing suppressor encoded by Rice stripe tenuivirus . Virology 2009, 387: 29-40. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.01.045

Wu J, Yu L, Li L, Hu J, Zhou J, Zhou X: Oral immunization with transgenic rice seeds expressing VP2 protein of infectious bursal disease virus induces protective immune responses in chickens. Plant Biotechnol J 2007, 5: 570-578. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00270.x

Hamilton AJ, Baulcombe DC: A species of small antisense RNA in posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants. Science 1999, 286: 950-952. 10.1126/science.286.5441.950

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Important National Science & Technology Specific Projects of China (2009ZX08009-026B) and the Grant from Yunnan Tobacco Company (07A03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

QH, YN, KZ, YL performed the experiments. QH, XZ analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. XZ provided overall direction and conducted experimental design, data analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Q., Niu, Y., Zhang, K. et al. Virus-derived transgenes expressing hairpin RNA give immunity to Tobacco mosaic virus and Cucumber mosaic virus. Virol J 8, 41 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-8-41

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-8-41