Abstract

In this paper, we discuss the existence of weak solutions for a nonlinear boundary value problem of fractional q-difference equations in Banach space. Our analysis relies on the Mönch’s fixed-point theorem combined with the technique of measures of weak noncompactness.

MSC:26A33, 34B15.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Fractional differential calculus is a discipline to which many researchers are dedicating their time, perhaps because of its demonstrated applications in various fields of science and engineering [1]. Many researchers studied the existence of solutions to fractional boundary value problems, for example, [2–10].

The q-difference calculus or quantum calculus is an old subject that was initially developed by Jackson [11, 12]; basic definitions and properties of q-difference calculus can be found in [13, 14].

The fractional q-difference calculus had its origin in the works by Al-Salam [15] and Agarwal [16]. More recently, maybe due to the explosion in research within the fractional differential calculus setting, new developments in this theory of fractional q-difference calculus were made, for example, q-analogues of the integral and differential fractional operators properties such as Mittage-Leffler function [17], just to mention some.

El-Shahed and Hassan [18] studied the existence of positive solutions of the q-difference boundary value problem:

Ferreira [19] considered the existence of positive solutions to nonlinear q-difference boundary value problem:

Ferreira [20] studied the existence of positive solutions to nonlinear q-difference boundary value problem:

El-Shahed and Al-Askar [21] studied the existence of positive solutions to nonlinear q-difference equation:

where and is the fractional q-derivative of the Caputo type.

Ahmad, Alsaedi and Ntouyas [22] discussed the existence of solutions for the second-order q-difference equation with nonseparated boundary conditions

where , , , and is a fixed constant, and is a fixed real number.

Ahmad and Nieto [23] discussed a nonlocal nonlinear boundary value problem (BVP) of third-order q-difference equations given by

where , , and is a fixed constant, and is a real number.

This paper is mainly concerned with the existence results for the following fractional q-difference equations:

where and is the fractional q-derivative of the Caputo type. is a given function satisfying some assumptions that will be specified later, and E is a Banach space with norm .

To investigate the existence of solutions of the problem above, we use Mönch’s fixed-point theorem combined with the technique of measures of weak noncompactness, which is an important method for seeking solutions of differential equations. This technique was mainly initiated in the monograph of Banaś and Goebel [24], and subsequently developed and used in many papers; see, for example, Banaś et al. [25], Guo et al. [26], Krzyska and Kubiaczyk [27], Lakshmikantham and Leela [28], Mönch [29], O’Regan [30, 31], Szufla [32, 33] and the references therein. As far as we know, there are very few results devoted to weak solutions of nonlinear fractional differential equations [34–38]. Motivated by the above mentioned papers, the purpose of this paper is to establish the existence results for the boundary value problem (1.1) by virtue of the Mönch’s fixed-point theorem combined with the technique of measures of weak noncompactness.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. In Section 2, we provide some basic definitions, preliminaries facts and various lemmas, which are needed later. In Section 3, we give main results of the problem (1.1). In the end, we also give an example for the illustration of the theories established in this paper.

2 Preliminaries and lemmas

In this section, we present some basic notations, definitions and preliminary results, which will be used throughout this paper.

Let and define [13]

The q-analogue of the power is

If α is not a positive integer, then

Note that if , then . The q-gamma function is defined by

and satisfies .

The q-derivative of a function f is here defined by

and q-derivatives of higher order by

The q-integral of a function f defined in the interval is given by

If and f is defined in the interval , its integral from a to b is defined by

Similarly, as done for derivatives, an operator can be defined, namely,

The fundamental theorem of calculus applies to these operators and , that is,

and if f is continuous at , then

Basic properties of the two operators can be found in the book mentioned in [13]. We now point out three formulas that will be used later ( denotes the derivative with respect to variable i) [19]

Remark 2.1 We note that if and , then [19].

Let and denote the Banach space of real-valued Lebesgue integrable functions on the interval J, denote the Banach space of real-valued essentially bounded and measurable functions defined over J with the norm .

Let E be a real reflexive Banach space with norm and dual , and let denote the space E with its weak topology. Here, is the Banach space of continuous functions with the usual supremum norm .

Moreover, for a given set V of functions , let us denote by , and .

Definition 2.1 A function is said to be weakly sequentially continuous if h takes each weakly convergent sequence in E to a weakly convergent sequence in E (i.e. for any in E with in then in for each ).

Definition 2.2 [39]

The function is said to be Pettis integrable on J if and only if there is an element corresponding to each such that for all , where the integral on the right is supposed to exist in the sense of Lebesgue. By definition, .

Let be the space of all E-valued Pettis integrable functions in the interval J.

Lemma 2.1 [39]

If is Pettis integrable and is a measurable and an essentially bounded real-valued function, then is Pettis integrable.

Definition 2.3 [40]

Let E be a Banach space, the set of all bounded subsets of E, and the unit ball in E. The De Blasi measure of weak noncompactness is the map defined by

Lemma 2.2 [40]

The De Blasi measure of noncompactness satisfies the following properties:

-

(a)

;

-

(b)

is relatively weakly compact;

-

(c)

;

-

(d)

, where denotes the weak closure of S;

-

(e)

;

-

(f)

;

-

(g)

;

-

(h)

.

The following result follows directly from the Hahn-Banach theorem.

Lemma 2.3 Let E be a normed space with . Then there exists with and .

Definition 2.4 [16]

Let and f be a function defined on . The fractional q-integral of the Riemann-Liouville type is and

Definition 2.5 [14]

The fractional q-derivative of the Riemann-Liouville type of order is defined by and

where is the smallest integer greater than or equal to α.

Definition 2.6 [14]

The fractional q-derivative of the Caputo type of order is defined by

where is the smallest integer greater than or equal to α.

Lemma 2.4 [14]

Let and let f be a function defined on . Then the next formulas hold:

-

(1)

,

-

(2)

.

Lemma 2.5 [32]

Let D be a closed convex and equicontinuous subset of a metrizable locally convex vector space such that . Assume that is weakly sequentially continuous. If the implication

holds for every subset V of D, then A has a fixed point.

3 Main results

Let us start by defining what we mean by a solution of the problem (1.1).

Definition 3.1 A function is said to be a solution of the problem (1.1) if u satisfies the equation on J, and satisfy the conditions , .

For the existence results on the problem (1.1), we need the following auxiliary lemmas.

Lemma 3.1 [19]

Let and . Then, the following equality holds:

Lemma 3.2 [14]

Let and . Then the following equality holds:

We derive the corresponding Green’s function for boundary value problem (1.1), which will play major role in our next analysis.

Lemma 3.3 Let be a given function, then the boundary-value problem

has a unique solution

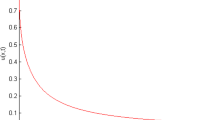

where is defined by the formula

Here, is called the Green’s function of boundary value problem (3.1).

Proof By Lemma 2.4 and Lemma 3.2, we can reduce the equation of problem (3.1) to an equivalent integral equation

Applying the boundary conditions , we have

So, we have

Then, by the condition , we have

Therefore, the unique solution of problem (3.1) is

which completes the proof. □

Remark 3.1 From the expression of , it is obvious that is continuous on . Denote by

To prove the main results, we need the following assumptions:

(H1) For each , the function is weakly sequentially continuous;

(H2) For each , the function is Pettis integrable on J;

(H3) There exists such that

(H3)′ There exists and a continuous nondecreasing function such that

(H4) For each bounded set , and each , the following inequality holds:

(H5) There exists a constant such that

where .

Theorem 3.1 Let E be a reflexive Banach space and assume that (H1)-(H3) are satisfied. If

then the problem (1.1) has at least one solution on J.

Proof Let the operator defined by the formula

where is the Green’s function defined by (3.3). It is well known the fixed points of the operator are solutions of the problem (1.1).

First notice that, for , we have (assumption (H2)). Since, , then is Pettis integrable for all by Lemma 2.1, and so the operator is well defined.

Let , and consider the set

Clearly, the subset D is closed, convex and equicontinuous. We shall show that satisfies the assumptions of Lemma 2.5. The proof will be given in three steps.

Step 1: We will show that the operator maps D into itself.

Take , and assume that . Then there exists such that . Thus,

Let , and , so . Then there exists , such that . Hence,

this means that .

Step 2: We will show that the operator is weakly sequentially continuous.

Let be a sequence in D and let in for each . Fix . Since f satisfies assumptions (H1), we have converge weakly uniformly to . Hence, the Lebesgue dominated convergence theorem for Pettis integrals implies converges weakly uniformly to in . Repeating this for each shows . Then is weakly sequentially continuous.

Step 3: The implication (2.1) holds. Now let V be a subset of D such that . Clearly, for all . Hence, , , is bounded in E. Thus, is weakly relatively compact since a subset of a reflexive Banach space is weakly relatively compact if and only if it is bounded in the norm topology. Therefore,

thus, V is relatively weakly compact in E. In view of Lemma 2.5, we deduce that has a fixed point, which is obviously a solution of the problem (1.1). This completes the proof. □

Remark 3.2 In Theorem 3.1, we presented an existence result for weak solutions of the problem (1.1) in the case where the Banach space E is reflexive. However, in the nonreflexive case, conditions (H1)-(H3) are not sufficient for the application of Lemma 2.5; the difficulty is with condition (2.1).

Theorem 3.2 Let E be a Banach space, and assume assumptions (H1), (H2), (H3), (H4) are satisfied. If (3.9) holds, then the problem (1.1) has at least one solution on J.

Theorem 3.3 Let E be a Banach space, and assume assumptions (H1), (H2), (H3)′, (H4), (H5) are satisfied. If (3.9) holds, then the problem (1.1) has at least one solution on J.

Proof Assume that the operator is defined by the formula (3.10). It is well known the fixed points of the operator are solutions of the problem (1.1).

First notice that, for , we have (assumption (H2)). Since, , then for all is Pettis integrable (Lemma 2.1), and thus, the operator makes sense.

Let , and consider the set

clearly, the subset is closed, convex and equicontinuous. We shall show that satisfies the assumptions of Lemma 2.5. The proof will be given in three steps.

Step 1: We will show that the operator maps into itself.

Take , and assume that . Then there exists such that . Thus,

Let , and , so . Then there exist such that

Thus,

this means that .

Step 2: We will show that the operator is weakly sequentially continuous.

Let be a sequence in and let in for each . Fix . Since f satisfies assumptions (H1), we have , converging weakly uniformly to . Hence, the Lebesgue dominated convergence theorem for Pettis integral implies converging weakly uniformly to in . We do it for each so . Then is weakly sequentially continuous.

Step 3: The implication (2.1) holds. Now let V be a subset of such that . Clearly, for all . Hence, , , is bounded in E. Using this fact, assumption (H4), Lemma 2.2 and the properties of the measure β, we have for each

which gives

This means that

By (3.9), it follows that , that is for each , and then is relatively weakly compact in E. In view of Lemma 2.5, we deduce that has a fixed point which is obviously a solution of the problem (1.1). This completes the proof. □

References

Podlubny I: Fractional Differential Equations. Academic Press, San Diego; 1999.

Kilbas AA, Srivastava HM, Trujillo JJ North-Holland Mathematical Studies 204. In Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations. Elsevier, Amsterdam; 2006.

Srivastava HM: Some generalizations and basic (or q -) extensions of the Bernoulli, Euler and Genocchi polynomials. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 2011, 5(3):390–444.

Srivastava HM, Choi J: Zeta and q-Zeta Functions and Associated Series and Integrals. Elsevier, Amsterdam; 2012.

El-Shahed M: Existence of solution for a boundary value problem of fractional order. Adv. Appl. Math. Anal. 2007, 2(1):1–8.

Zhang S: Existence of solution for a boundary value problem of fractional order. Acta Math. Sci. 2006, 26(2):220–228.

El-Shahed M, Al-Askar FM: On the existence of positive solutions for a boundary value problem of fractional order. Int. J. Math. Anal. 2010, 4(13–16):671–678.

Bai Z, Lü H: Positive solutions for boundary value problem of nonlinear fractional differential equation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2005, 311(2):495–505. 10.1016/j.jmaa.2005.02.052

Zhou W, Chu Y: Existence of solutions for fractional differential equations with multi-point boundary conditions. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2012, 17(3):1142–1148. 10.1016/j.cnsns.2011.07.019

Zhou W, Peng J, Chu Y: Multiple positive solutions for nonlinear semipositone fractional differential equations. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2012., 2012: Article ID 850871. doi:10.1155/2012/850871

Jackson FH: On q -functions and a certain difference operator. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 1908, 46: 253–281.

Jackson R: On q -definite integrals. Q. J. Pure Appl. Math. 1910, 41: 193–203.

Kac V, Cheung P: Quantum Calculus. Springer, New York; 2002.

Stanković, MS, Rajković, PM, Marinković, SD: On q-fractional derivatives of Riemann-Liouville and Caputo type. http://arxiv.org/abs/0909.0387(2009)

Al-Salam WA: Some fractional q -integrals and q -derivatives. Proc. Edinb. Math. Soc. 1967, 15(2):135–140.

Agarwal RP: Certain fractional q -integrals and q -derivatives. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1969, 66: 365–370. 10.1017/S0305004100045060

Rajković PM, Marinković SD, Stanković MS: On q -analogues of Caputo derivative Mittag-Leffler function. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2007, 10(4):359–373.

El-Shahed M, Hassan HA: Positive solutions of q -difference equation. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2010, 138(5):1733–1738.

Ferreira RAC: Nontrivial solutions for fractional q -difference boundary value problems. Electron. J. Qual. Theory Differ. Equ. 2010., 2010: Article ID 70

Ferreira RAC: Positive solutions for a class of boundary value problems with fractional q -differences. Comput. Math. Appl. 2011, 61(2):367–373. 10.1016/j.camwa.2010.11.012

El-Shahed M, Al-Askar FM: Positive solutions for boundary value problem of nonlinear fractional q -difference equation. ISRN Math. Anal. 2011., 2011: Article ID 385459. doi:10.5402/2011/385459

Ahmad B, Alsaedi A, Ntouyas SK: A study of second-order q -difference equations with boundary conditions. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2012., 2012: Article ID 35. doi:10.1186/1687–1847–2012–35

Ahmad B, Nieto JJ: On nonlocal boundary value problems of nonlinear q -difference equations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2012., 2012: Article ID 81. doi:10.1186/1687–1847–2012–81

Banaś J, Goebel K: Measures of Noncompactness in Banach Spaces. Dekker, New York; 1980.

Banaś J, Sadarangani K: On some measures of noncompactness in the space of continuous functions. Nonlinear Anal. 2008, 68(2):377–383. 10.1016/j.na.2006.11.003

Guo D, Lakshmikantham V, Liu X 373. In Nonlinear Integral Equations in Abstract Spaces. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht; 1996.

Krzyska S, Kubiaczyk I: On bounded pseudo and weak solutions of a nonlinear differential equation in Banach spaces. Demonstr. Math. 1999, 32(2):323–330.

Lakshmikantham V, Leela S 2. In Nonlinear Differential Equations in Abstract Spaces. Pergamon, Oxford; 1981.

Mönch H: Boundary value problems for nonlinear ordinary differential equations of second order in Banach spaces. Nonlinear Anal. 1980, 4(5):985–999. 10.1016/0362-546X(80)90010-3

O’Regan D: Fixed point theory for weakly sequentially continuous mapping. Math. Comput. Model. 1998, 27(5):1–14. 10.1016/S0895-7177(98)00014-4

O’Regan D: Weak solutions of ordinary differential equations in Banach spaces. Appl. Math. Lett. 1999, 12(1):101–105. 10.1016/S0893-9659(98)00133-5

Szufla S: On the application of measure of noncompactness to existence theorems. Rend. Semin. Mat. Univ. Padova 1986, 75: 1–14.

Szufla S, Szukala A: Existence theorems for weak solutions of n th order differential equations in Banach spaces. Funct. Approx. Comment. Math. 1998, 26: 313–319. Dedicated to Julian Musielak

Salem HAH: On the fractional order m -point boundary value problem in reflexive Banach spaces and weak topologies. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2009, 224(2):565–572. 10.1016/j.cam.2008.05.033

Salem HAH, El-Sayed AMA, Moustafa OL: A note on the fractional calculus in Banach spaces. Studia Sci. Math. Hung. 2005, 42(2):115–130.

Benchohra M, Graef JR, Mostefai FZ: Weak solutions for nonlinear fractional differential equations on reflexive Banach spaces. Electron. J. Qual. Theory Differ. Equ. 2010., 2010: Article ID 54

Zhou W, Chang Y, Liu H: Weak solutions for nonlinear fractional differential equations in Banach spaces. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2012., 2012: Article ID 527969. doi:10.1155/2012/527969

Zhou W, Liu H: Existence of weak solutions for nonlinear fractional differential inclusion with non-separated boundary conditions. J. Appl. Math. 2012., 2012: Article ID 530624. doi:10.1155/2012/530624

Pettis BJ: On integration in vector spaces. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1938, 44(2):277–304. 10.1090/S0002-9947-1938-1501970-8

De Blasi FS: On the property of the unit sphere in a Banach space. Bull. Math. Soc. Sci. Math. Répub. Social. Roum. 1977, 21(3–4):259–262.

Acknowledgements

Dedicated to Professor Hari M Srivastava.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11161027, 11262009). The authors are thankful to the referees for their careful reading of the manuscript and insightful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, WX., Liu, HZ. Existence solutions for boundary value problem of nonlinear fractional q-difference equations. Adv Differ Equ 2013, 113 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-1847-2013-113

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-1847-2013-113