Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between a purported luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin (LHCGR) high function polymorphism (rs4539842/insLQ) and outcome to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH).

Methods

This was a prospective study of 172 patients undergoing COH at the Fertility and IVF Center at GWU. DNA was isolated from blood samples and a region encompassing the insLQ polymorphism was sequenced. We also investigated a polymorphism (rs4073366 G > C) that was 142 bp from insLQ. The association of the insLQ and rs4073366 alleles and outcome to COH (number of mature follicles, estradiol level on day of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) administration, the number of eggs retrieved and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS)) was determined.

Results

Increasing age and higher day 3 (basal) FSH levels were significantly associated with poorer response to COH. We found that both insLQ and rs4073366 were in linkage disequilibrium (LD) and no patients were homozygous for both recessive alleles (insLQ/insLQ; C/C). The insLQ variant was not significantly associated with any of the main outcomes to COH. Carrier status for the rs4073366 C variant was associated (P = 0.033) with an increased risk (OR 2.95, 95% CI = 1.09-7.96) of developing OHSS.

Conclusions

While age and day 3 FSH levels were predictive of outcome, we found no association between insLQ and patient response to COH. Interestingly, rs4073366 C variant carrier status was associated with OHSS risk. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report suggesting that LHCGR genetic variation might function in patient risk for OHSS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Controlled ovulation hyperstimulation (COH) is the cornerstone of assisted reproduction. The use of exogenous gonadotropins subverts the natural process of single follicular dominance and allows for the recruitment and maturation of multiple ova during the ovarian cycle. Although this technique has vastly enhanced the potential for in vitro fertilization (IVF) success, individual patients still have disparate responses. Various phenotypic predictors of ovarian responsiveness (i.e. ovarian reserve testing (ORT)) [1–4] have been used to titrate doses of fertility medications. Despite such predictors, gonadotropin dosing remains somewhat empiric and thus, patients risk under or over responding (ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS)) to these drugs. Pharmacogenetic biomarkers offer promise for aiding in the a priori determination of patient response to COH [5] and minimizing complications. To date, most work has focused on common variant alleles of follicle stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) [6–17], estrogen receptor (ESR) [6–8, 18–20] and aromatase (CYP19A1) [6, 21] genes as well as several other genetic loci [8, 10, 22, 23] which have offered some promising predictive biomarkers for COH outcome.

The luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) protein is a G protein-coupled hormone receptor (GPCR) [24] and is expressed in numerous tissues including the gonads [25, 26], uterus [26–28], fallopian tubes [29], placenta and fetus [30]. Both LH and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) are endogenous ligands for LHR [31] with the latter also employed during COH. Prior to ovulation, FSH and estradiol both increase pituitary production of LH and induce LHR expression in the ovaries where LHR functions in promoting follicular maturation, lutenization and ovulation [32]. During assisted reproduction, it is believed that hCG administration (i.e. hCG trigger) activates LHR-mediated signaling. The pharmacological use of hCG for COH has been implicated in the increased ovarian vascular permeability associated with OHSS, an iatrogenic complication of COH [33–36].

LHR is encoded by the luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor (LHCGR) gene (~69 kb) located on chromosome 2p21 [37–39]. LHCGR harbors at least 300 known polymorphisms [40–42] some of which having a significant impact on sexual development and fertility [43–51]. Recently, a 6 base-pair (CTCCAG) insertion in exon 1 (rs4539842; insLQ) has been reported that results in the addition of two amino acids (Leu-Gln) in the signal peptide region of the receptor [42, 52–54]. The allelic frequency of the insLQ polymorphism is approximately 0.3 in individuals of Caucasian and African descent [54, 55]. Structurally, insLQ impacts LHR by potentially altering protein folding, trafficking and membrane insertion. Functionally, the insLQ variant LHR protein displays higher activity in cell culture potentially due to improved trafficking and increased cell surface expression, but unrelated to alterations in hCG binding [52]. Breast cancer patients carrying the insLQ allele exhibit shorter disease-free survival than non-carriers [52, 53]. In addition, LHCGR resides near a potential susceptibility locus for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which is characterized by anovulation/oligo-ovulation and elevated androgen levels [56]. In a small case/control study (n = 72), insLQ was detected at a higher level (40.5%) in patients who experienced ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) compared to controls (27.5%), but this did not achieve statistical significance potentially due to a small sample size [57].

Patient response to COH is multi-factorial in nature. To date, there is no reliable test or algorithm that combines both genetic and clinical factors for predicting patient response to fertility therapy. As a result, the focus of this ongoing work is to identify genetic factors that are predictive of clinical response to COH. The insLQ allele appears to result in an LHR protein with increased in vitro activity; it is therefore possible that this polymorphism could significantly impact patient response to COH. The objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between the LHCGR insLQ and clinical response to COH. Interestingly, the results suggest that insLQ has little impact on COH outcome. However, carriers of a single nucleotide polymorphism (rs4073366 G > C) nearby insLQ exhibited an increased risk of developing OHSS.

Methods

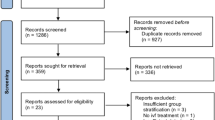

This study was approved by George Washington University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants of this study. The study was open to all adult (>18 years of age), female patients seeking treatment at the GW Fertility and IVF Center at GWU Medical Center. One hundred seventy-two patients were recruited into the study from 2010–2011. All IVF patients being monitored while taking injectable gonadotropins were invited to participate. Prior to beginning treatment, all patients had undergone an evaluation that included ovarian reserve testing, semen analysis (male partner), uterine cavity study and thyroid screening. Controlled ovarian stimulation was accomplished with either luteal down regulation using a GnRH agonist (leuprolide acetate; TAP Pharmaceuticals) followed by recombinant FSH (Follistim; Merck & Co; or Gonal-F, Serono) administration or with recombinant FSH (Follistim; Merck & Co; or Gonal-F, Serono) administration in combination with a GnRH antagonist (Antagon; Merck & Co). The initial FSH dose was dependent upon patient age and basal ovarian reserve testing. After initial follicular monitoring (serum estradiol and transvaginal ultrasound assessments), FSH dosing was titrated based upon the ovarian response. hCG trigger was withheld for levels E2 over 4000 pg/ml thus minimizing risk for OHSS. Both control and OHSS groups had similar risk factors including those identified at time of hCG trigger. Ovarian response to gonadotropin was observed. The primary endpoint of the study was the estradiol level on day of hCG injection. Secondary clinical endpoints included number of ovarian follicles counted on day of hCG number of eggs retrieved and the incidence of OHSS. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome was defined clinically based on the criteria established by Navot [58, 59].

Approximately 5 mL of blood was collected for genetic analysis at the GW IVF Center. Total genomic DNA was extracted from 200 μl EDTA anti-coagulated venous blood using a QiaCube automated instrument with the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The samples were frozen at −80°C until the time of genotyping. A 291 base-pair target region encompassing (rs4539842/insLQ and rs4073366 was amplified using 10 pmol/μl forward (5’-CACTCAGAGGCCGTCCAAG-3’) and reverse (5’-GGAGGGAAGGTGGCATAGAG-3’) primers [42]. PCR was performed in a reaction volume of 50 μl, including 10.0 μl of 5X Reaction Buffer, 0.5 μl GoTaq L nucleotide mix, 6 μl MgCl2 DNA Polymerase (Promega Corp, Madison, WI), 3.75 μl of H2O, and 10.0 μl of genomic DNA. The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 32 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 56°C for 30 seconds and 72°C for 30 seconds and a 7 min final extension at 72°C. PCR products were purified (GeneClean Turbo, MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) and 20–40 ng/μl of samples were sequenced using BigDye Terminator technology (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) by Eurofins MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL). Multiple sequence alignments were carried out using ChromasPro software (Technelysium Pty Ltd).

Patient differences in mean outcomes (estradiol level, number of follicles, number of eggs retrieved) related to genotype were tested using a step-down bootstrap resampling method (the STEPBOOT option in PROC MULTTEST in SAS) [60]. This method adjusts for multiple comparisons while maintaining relatively good statistical power compared to other methods and is applicable to both normal and non-normally distributed data [60]. Outcome differences were first tested separately for each polymorphism, followed by comparing combinations of alleles for the two polymorphisms. The association between the distributions of patients across alleles for the two polymorphisms was tested by Fisher’s Exact Test. Multivariable model predicting each outcome was calculated using linear regression for estradiol level and negative-binomial regression for number of follicles and eggs retrieved. The latter method is an extension of Poisson regression. SAS v.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses. Polymorphisms and were analyzed for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and linkage disequilibrium (LD) using PyPop: Python of Population Genomics software [61], CubeX [62] and SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY). Unadjusted odds ratios for OHSS risk were determined using SAS v.9.2 and SPSS.

Results

A total of 172 patients underwent IVF and were genotyped. The mean age of the patient population was 36.8 years old (Table 1). The majority of the population was Caucasian (57.0%) followed by Asian/Pacific Islander (15.7%), non-Hispanic, African American (11.1%) and Hispanic (2%). Because there were few Hispanic patients, for analysis we grouped these individuals with those for which no self-identified ethnic/ancestral information was available (16.3% of sample). Median levels of ovarian reserve markers TSH, day 3 follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and day 3 estradiol (E2) levels, were 1.8 IU/ml, 7.0 IU/L, and 40.8 pg/ml, respectively. On average, patient gonadotropin stimulation lasted 12 days. Mean E2 levels on the day of hCG administration was 1780 pg/ml and the median number of follicles and eggs retrieved was 10 and 9, respectively. Eighteen patients (10.5%) experienced moderate to severe OHSS (Table 1). The OHSS cases in our sample were similar to the 154 non-OHSS patients on age and most relevant clinical variables, with the exception of being more likely to be Black, less likely to be Asian. OHSS cases also had higher numbers of follicles, a higher mean estradiol level on day of hCG and more eggs retrieved (Table 1). These three clinical differences were expected based on the nature of OHSS.

Recently, a novel, potentially inactivating, mutation was detected that resided within the insLQ insertion (CTGCA > CG) in a patient with poor oocyte recovery following IVF [44]. This mutation would not have been identified using fragment analysis (the commonly employed method for detecting insLQ). As a result, we analyzed insLQ through direct sequencing of a 291 base-pair region of exon/intron 1. As shown in Table 2, relative allelic proportions for no-insLQ/no-insLQ, no-insLQ/insLQ and insLQ/insLQ were ~0.62, 0.34 and 0.035, respectively (n = 172). Another polymorphism, rs4073366 G > C, occurs ~142 bp downstream of insLQ and was detected during sequencing. We attempted alternative methods (TaqMan® probe, alternative primer pairs) to omit rs4073366 from our study of insLQ, but these yielded unreliable results. Consequently, we included this single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in our analysis because of its potential impact on any apparent associations between insLQ and COH outcome. For rs4073366, G/G, G/C and C/C variants occurred at relative proportions of ~0.72, 0.25 and 0.03, respectively in our patient population. Both variants were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and insLQ and rs4073366 were in significant LD (D’ = 1.0, P < 0.0001) as determined by pair-wise LD estimation (Table 2) (49). Homozygosity or heterozygosity for insLQ was associated with not being CG or CC for rs4073366 (Table 3, P = 0.012). In addition, we did not find any individuals who were homozygous for both insLQ and rs4073366, nor did we identify any patients who had the insLQ, rs4073366 “C” haplotype (data not shown).

Of the 172 patients, up to 17 patients were excluded (depending on the clinical endpoint) from multivariable analysis because of missing data values related to being screened at outside centers that did not have complete ovarian reserve testing or they did not undergo follicular monitoring on day of hCG administration. Both age and ORT (day 3 FSH, TSH and E2 levels) have been prognostic clinical indicators of outcome to COH (52). As a result, regression models predicting estradiol level on day of HCG, number of follicles, and number of eggs retrieved included age, day 3 FSH level, day 3 estradiol levels, and the insLQ and rs4073366 polymorphisms as covariates. In the multivariable models (Table 4), patient age was significantly associated with lower E2 levels on day of hCG (P = 0.03), fewer number of follicles (P < 0.0001) and a lower number of eggs retrieved (P = 0.0002). Increasing basal FSH level was associated with fewer follicles (P = 0.009) and eggs retrieved (P = 0.0002), but not E2 levels (P = 0.46) on day of hCG. All three main outcomes were positively correlated with each other (Spearman r, P < 0.0001) (data not shown). Finally, self-identified race/ethnicity was not significantly associated with any of the three main patient outcome measures (data not shown).

None of the pairwise differences comparing estradiol levels, number of follicles, and number of eggs retrieved among the 3 insLQ genotypes reached statistical significance (not shown). Similarly, results for rs4073366 genotype were also not significant for these three outcomes (not shown). We next examined the 6 non-zero combination genotypic groups and, again, found no significant differences for any of the outcomes when each mean was compared to the overall mean (Table 5). However, there was a non-significant trend for those individuals who did not carry insLQ and were heterozygous (GC) for rs4073366 (i.e. no-insLQ/no-insLQ + CG) to have increased mean estradiol level on day of hCG compared to the mean across all other groups (P = 0.10). The insLQ polymorphism (and rs4073366) was not associated with IVF protocol type, age, or basal FSH or E2 levels (data not shown).

The insLQ variant is purportedly a high-function allele and, accordingly, might place patients at a higher risk of OHSS. As a result, we tested whether either insLQ or rs4073366 were associated with an increased risk of OHSS. Because of the small number of OHSS patients, logistic regression analyses were performed without adjustment for covariates. Intriguingly, the insLQ variant was not associated with OHSS by either genotype (P = 0.788) (data not shown) or insLQ carrier status (Table 6). There was a non-significant (P = 0.07) trend towards an association between rs4073366 genotype and OHSS. When rs4073366 carrier status was included in our analysis, carriers of the rs4073366 C allele exhibited a significantly (P = 0.033) higher risk of OHSS (OR = 2.95, 95% CI = 1.09-7.96). Further haplotype analysis revealed that only the no-insLQ/C haplotype was significant (P = 0.023) for OHSS risk (OR = 2.46, 95% CI 1.11-5.46) (data not shown).

Discussion

LHR-mediated signaling plays an important role in patient response to exogenous gonadotropins (i.e. hCG) administered during COH and inter-individual variability in LHR activity could significantly impact outcome. As a result, we investigated whether LHCGR genetic variation influences response to COH. We focused our analysis on the insLQ polymorphism (rs4539842) and the rs4073366 G > C SNP located downstream of insLQ in intron 1. We found that insLQ was not associated with patient response to COH, nor was it a predictor for OHSS. Therefore, it is possible that the improved function conferred to LHR by this polymorphism in vitro[52] is not reflective of the situation in the ovaries. Moreover, insLQ activity was previously investigated in HEK-293 cells which may not accurately replicate the behavior of the insLQ receptor variant ovarian granulosa cells [52]. In contrast, we found that carriers of the rs4073366 “C” allele exhibited a ~3-fold increased risk of developing OHSS.

Very little information exists regarding polymorphisms that are predictive of patients developing OHSS. For example, the FSHR Thr307Ala polymorphism has been linked with iatrogenic OHSS in an Indian population [63], but not in European [9] or Brazilian patients [64]. The well-studied Asn680Ser FSHR polymorphism has not been associated with OHSS, but it is potentially predictive of the severity of symptoms [9]. In addition, BMP15 variation, such as the rs3810682 SNP (OR = 2.7, 95% CI = 1.3-5.7), has also been implicated in OHSS [23, 65]. Finally, VEGFA gene variation was recently identified as a risk allele (OR = 3.4, 95% CI = 1.01-11.7) for OHSS [66]. Given the paucity of genetic risk factors for OHSS, one of the most significant findings of this work was the association of rs4073366 C allele carrier status with increased risk of OHSS (OR = 2.95, 95% CI 1.09-7.96, Table 6) during COH. Furthermore, it seems that the effect of rs4073366 on OHSS risk was largely related to the no-insLQ/C haplotype (OR = 2.46, 95% CI 1.11-5.46) (data not shown). This interesting finding requires further investigation in other COH populations and suggests that the LHCGR genetic variation influences OHSS development. A recent genome-wide association study found that LHCGR was associated with serum steroid hormone binding globulin (SHBGs) levels (62), which could result in elevated serum concentrations of androgens and estrogen. However, the impact of LHCGR polymorphisms (i.e. insLQ, rs4073366) on SHBG levels in not currently known.

While rs4073366 is a potential predictor of OHSS risk, the functional consequences of this polymorphism on LHR function are yet to be elucidated. rs4073366 has a major allele of “C” on the “+” strand (“G” on the “-“strand in this study) and resides in a cryptic 3’ splice acceptor site (data not shown) which could potentially impact LHCGR mRNA processing yielding a splice variant with altered activity [67]. In addition, the intronic region surrounding rs4073366 is complementary to APOE mRNA and has been associated with decreased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in males carrying the APOE ϵ4 allele [67]. Given that apolipoprotein E is important for cholesterol uptake and steroidogenesis, and genetic variation in APOE has been linked to reproductive efficiency [68–70], it is possible that rs4073366 may alter response to fertility drugs via modulation of APOE mRNA stability. Although beyond the scope of this investigation; future work is focused on investigating the molecular consequences of rs4073366 on LHCGR function.

Conclusions

Outcome to COH is multi-factorial, variable and unpredictable. There have been few studies that have investigated LHCGR variability and its influence on COH. Here, we provide the first report of an association between LHCGR genetic variability and OHSS risk. The relevance of the rs4073366 polymorphism OHSS should be evaluated in additional patient populations. In addition, because OHSS is multigenic in nature, future work is warranted to investigate whether rs4073366, and other LHCGR variants, genetically interact with other loci to predict patient response to COH.

Abbreviations

- COH:

-

Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation

- OHSS:

-

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism.

References

Scott RT, Toner JP, Muasher SJ, Oehninger S, Robinson S, Rosenwaks Z: Follicle-stimulating hormone levels on cycle day 3 are predictive of in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 1989, 51: 651-654.

Licciardi FL, Liu HC, Rosenwaks Z: Day 3 estradiol serum concentrations as prognosticators of ovarian stimulation response and pregnancy outcome in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1995, 64: 991-994.

Ficicioglu C, Kutlu T, Baglam E, Bakacak Z: Early follicular antimullerian hormone as an indicator of ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 2006, 85: 592-596. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.019.

Hsu A, Arny M, Knee AB, Bell C, Cook E, Novak AL, Grow DR: Antral follicle count in clinical practice: analyzing clinical relevance. Fertil Steril. 2011, 95: 474-479. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.023.

Alviggi C, Humaidan P, Ezcurra D: Hormonal, functional and genetic biomarkers in controlled ovarian stimulation: tools for matching patients and protocols. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012, 10: 9-10.1186/1477-7827-10-9.

Altmae S, Hovatta O, Stavreus-Evers A, Salumets A: Genetic predictors of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation: where do we stand today?. Hum Reprod Update. 2011, 17: 813-828. 10.1093/humupd/dmr034.

Anagnostou E, Mavrogianni D, Theofanakis C, Drakakis P, Bletsa R, Demirol A, Gurgan T, Antsaklis A, Loutradis D: ESR1, ESR2 and FSH receptor gene polymorphisms in combination: a useful genetic tool for the prediction of poor responders. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012, 13: 426-434. 10.2174/138920112799361891.

Boudjenah R, Molina-Gomes D, Torre A, Bergere M, Bailly M, Boitrelle F, Taieb S, Wainer R, Benahmed M, De Mazancourt P, et al: Genetic polymorphisms influence the ovarian response to rFSH stimulation in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization programs with ICSI. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e38700-10.1371/journal.pone.0038700.

Daelemans C, Smits G, De Maertelaer V, Costagliola S, Englert Y, Vassart G, Delbaere A: Prediction of severity of symptoms in iatrogenic ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome by follicle-stimulating hormone receptor Ser680Asn polymorphism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 89: 6310-6315. 10.1210/jc.2004-1044.

De Castro F, Moron FJ, Montoro L, Galan JJ, Hernandez DP, Padilla ES, Ramirez-Lorca R, Real LM, Ruiz A: Human controlled ovarian hyperstimulation outcome is a polygenic trait. Pharmacogenetics. 2004, 14: 285-293. 10.1097/00008571-200405000-00003.

Desai SS, Achrekar SK, Pathak BR, Desai SK, Mangoli VS, Mangoli RV, Mahale SD: Follicle-stimulating hormone receptor polymorphism (G-29A) is associated with altered level of receptor expression in Granulosa cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011, 96: 2805-2812. 10.1210/jc.2011-1064.

Jun JK, Yoon JS, Ku SY, Choi YM, Hwang KR, Park SY, Lee GH, Lee WD, Kim SH, Kim JG, Moon SY: Follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene polymorphism and ovarian responses to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for IVF-ET. J Hum Genet. 2006, 51: 665-670. 10.1007/s10038-006-0005-5.

Loutradis D, Patsoula E, Minas V, Koussidis GA, Antsaklis A, Michalas S, Makrigiannakis A: FSH receptor gene polymorphisms have a role for different ovarian response to stimulation in patients entering IVF/ICSI-ET programs. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2006, 23: 177-184. 10.1007/s10815-005-9015-z.

Lussiana C, Guani B, Mari C, Restagno G, Massobrio M, Revelli A: Mutations and polymorphisms of the FSH receptor (FSHR) gene: clinical implications in female fecundity and molecular biology of FSHR protein and gene. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008, 63: 785-795. 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31818957eb.

Sheikhha MH, Eftekhar M, Kalantar SM: Investigating the association between polymorphism of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene and ovarian response in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2011, 4: 86-90. 10.4103/0974-1208.86089.

Wunsch A, Ahda Y, Banaz-Yasar F, Sonntag B, Nieschlag E, Simoni M, Gromoll J: Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter region influence the expression of the human follicle-stimulating hormone receptor. Fertil Steril. 2005, 84: 446-453. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.02.031.

Wunsch A, Sonntag B, Simoni M: Polymorphism of the FSH receptor and ovarian response to FSH. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2007, 68: 160-166. 10.1016/j.ando.2007.04.006.

Altmae S, Haller K, Peters M, Hovatta O, Stavreus-Evers A, Karro H, Metspalu A, Salumets A: Allelic estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) gene variants predict the outcome of ovarian stimulation in in vitro fertilization. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007, 13: 521-526. 10.1093/molehr/gam035.

Georgiou I, Konstantelli M, Syrrou M, Messinis IE, Lolis DE: Oestrogen receptor gene polymorphisms and ovarian stimulation for in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1997, 12: 1430-1433. 10.1093/humrep/12.7.1430.

Loutradis D, Theofanakis C, Anagnostou E, Mavrogianni D, Partsinevelos GA: Genetic profile of SNP(s) and ovulation induction. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012, 13: 417-425. 10.2174/138920112799361954.

Altmae S, Haller K, Peters M, Saare M, Hovatta O, Stavreus-Evers A, Velthut A, Karro H, Metspalu A, Salumets A: Aromatase gene (CYP19A1) variants, female infertility and ovarian stimulation outcome: a preliminary report. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009, 18: 651-657. 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60009-0.

Wang TT, Wu YT, Dong MY, Sheng JZ, Leung PC, Huang HF: G546A polymorphism of growth differentiation factor-9 contributes to the poor outcome of ovarian stimulation in women with diminished ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 2010, 94: 2490-2492. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.070.

Hanevik HI, Hilmarsen HT, Skjelbred CF, Tanbo T, Kahn JA: A single nucleotide polymorphism in BMP15 is associated with high response to ovarian stimulation. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011, 23: 97-104. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.02.015.

Hillier SG: Gonadotropic control of ovarian follicular growth and development. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001, 179: 39-46. 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00469-5.

Webb R, Nicholas B, Gong JG, Campbell BK, Gutierrez CG, Garverick HA, Armstrong DG: Mechanisms regulating follicular development and selection of the dominant follicle. Reprod Suppl. 2003, 61: 71-90.

Ziecik AJ, Kaczmarek MM, Blitek A, Kowalczyk AE, Li X, Rahman NA: Novel biological and possible applicable roles of LH/hCG receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007, 269: 51-60. 10.1016/j.mce.2006.08.016.

Ziecik AJ, Derecka-Reszka K, Rzucidlo SJ: Extragonadal gonadotropin receptors, their distribution and function. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992, 43: 33-49.

Ziecik AJ, Derecka K, Gawronska B, Stepien A, Bodek G: Nongonadal LH/hCG receptors in pig: functional importance and parallels to human. Semin Reprod Med. 2001, 19: 19-30. 10.1055/s-2001-13907.

Gawronska B, Paukku T, Huhtaniemi I, Wasowicz G, Ziecik AJ: Oestrogen-dependent expression of LH/hCG receptors in pig Fallopian tube and their role in relaxation of the oviduct. J Reprod Fertil. 1999, 115: 293-301. 10.1530/jrf.0.1150293.

Perrier d’Hauterive S, Berndt S, Tsampalas M, Charlet-Renard C, Dubois M, Bourgain C, Hazout A, Foidart JM, Geenen V: Dialogue between blastocyst hCG and endometrial LH/hCG receptor: which role in implantation?. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007, 64: 156-160. 10.1159/000101740.

Hearn MT, Gomme PT: Molecular architecture and biorecognition processes of the cystine knot protein superfamily: part I. The glycoprotein hormones. J Mol Recognit. 2000, 13: 223-278. 10.1002/1099-1352(200009/10)13:5<223::AID-JMR501>3.0.CO;2-L.

Ascoli M, Fanelli F, Segaloff DL: The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor, a 2002 perspective. Endocr Rev. 2002, 23: 141-174. 10.1210/er.23.2.141.

Kumar P, Sait SF, Sharma A, Kumar M: Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2011, 4: 70-75. 10.4103/0974-1208.86080.

Cerrillo M, Pacheco A, Rodriguez S, Gomez R, Delgado F, Pellicer A, Garcia-Velasco JA: Effect of GnRH agonist and hCG treatment on VEGF, angiopoietin-2, and VE-cadherin: trying to explain the link to ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2011, 95: 2517-2519. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.12.054.

Vardhana PA, Julius MA, Pollak SV, Lustbader EG, Trousdale RK, Lustbader JW: A unique human chorionic gonadotropin antagonist suppresses ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in rats. Endocrinology. 2009, 150: 3807-3814. 10.1210/en.2009-0107.

Van de Lagemaat R, Raafs BC, Van Koppen C, Timmers CM, Mulders SM, Hanssen RG: Prevention of the onset of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) in the rat after ovulation induction with a low molecular weight agonist of the LH receptor compared with hCG and rec-LH. Endocrinology. 2011, 152: 4350-4357. 10.1210/en.2011-1077.

Fanelli F, Puett D: Structural aspects of luteinizing hormone receptor: information from molecular modeling and mutagenesis. Endocrine. 2002, 18: 285-293. 10.1385/ENDO:18:3:285.

Fanelli F, Themmen AP, Puett D: Lutropin receptor function: insights from natural, engineered, and computer-simulated mutations. IUBMB Life. 2001, 51: 149-155. 10.1080/152165401753544214.

Fanelli F, Verhoef-Post M, Timmerman M, Zeilemaker A, Martens JW, Themmen AP: Insight into mutation-induced activation of the luteinizing hormone receptor: molecular simulations predict the functional behavior of engineered mutants at M398. Mol Endocrinol. 2004, 18: 1499-1508. 10.1210/me.2003-0050.

Themmen AP: An update of the pathophysiology of human gonadotrophin subunit and receptor gene mutations and polymorphisms. Reprod Suppl. 2005, 130: 263-274.

Minegishi T, Nakamura K, Takakura Y, Miyamoto K, Hasegawa Y, Ibuki Y, Igarashi M, Minegish T: Cloning and sequencing of human LH/hCG receptor cDNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990, 172: 1049-1054. 10.1016/0006-291X(90)91552-4.

Atger M, Misrahi M, Sar S, Le Flem L, Dessen P, Milgrom E: Structure of the human luteinizing hormone-choriogonadotropin receptor gene: unusual promoter and 5’ non-coding regions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1995, 111: 113-123. 10.1016/0303-7207(95)03557-N.

Mongan NP, Hughes IA, Lim HN: Evidence that luteinising hormone receptor polymorphisms may contribute to male undermasculinisation. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002, 147: 103-107. 10.1530/eje.0.1470103.

Bentov Y, Kenigsberg S, Casper RF: A novel luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor mutation associated with amenorrhea, low oocyte yield, and recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 2012, 97: 1165-1168. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.002.

Simoni M, Tuttelmann F, Michel C, Bockenfeld Y, Nieschlag E, Gromoll J: Polymorphisms of the luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor gene: association with maldescended testes and male infertility. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008, 18: 193-200. 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f4e98c.

Kossack N, Troppmann B, Richter-Unruh A, Kleinau G, Gromoll J: Aberrant transcription of the LHCGR gene caused by a mutation in exon 6A leads to Leydig cell hypoplasia type II. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013, 366: 59-67. 10.1016/j.mce.2012.11.018.

Latronico AC, Arnhold IJ: Inactivating mutations of the human luteinizing hormone receptor in both sexes. Semin Reprod Med. 2012, 30: 382-386. 10.1055/s-0032-1324721.

Yariz KO, Walsh T, Uzak A, Spiliopoulos M, Duman D, Onalan G, King MC, Tekin M: Inherited mutation of the luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHCGR) in empty follicle syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2011, 96: e125-130. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.057.

Qiao J, Han B, Liu BL, Chen X, Ru Y, Cheng KX, Chen FG, Zhao SX, Liang J, Lu YL, et al: A splice site mutation combined with a novel missense mutation of LHCGR cause male pseudohermaphroditism. Hum Mutat. 2009, 30: E855-865. 10.1002/humu.21072.

Arnhold IJ, Lofrano-Porto A, Latronico AC: Inactivating mutations of luteinizing hormone beta-subunit or luteinizing hormone receptor cause oligo-amenorrhea and infertility in women. Horm Res. 2009, 71: 75-82.

Segaloff DL: Diseases associated with mutations of the human lutropin receptor. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2009, 89: 97-114.

Piersma D, Berns EM, Verhoef-Post M, Uitterlinden AG, Braakman I, Pols HA, Themmen AP: A common polymorphism renders the luteinizing hormone receptor protein more active by improving signal peptide function and predicts adverse outcome in breast cancer patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006, 91: 1470-1476. 10.1210/jc.2005-2156.

Piersma D, Themmen AP, Look MP, Klijn JG, Foekens JA, Uitterlinden AG, Pols HA, Berns EM: GnRH and LHR gene variants predict adverse outcome in premenopausal breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2007, 9: R51-10.1186/bcr1756.

Rodien P, Cetani F, Costagliola S, Tonacchera M, Duprez L, Minegishi T, Govaerts C, Vassart G: Evidences for an allelic variant of the human LC/CG receptor rather than a gene duplication: functional comparison of wild-type and variant receptors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998, 83: 4431-4434. 10.1210/jc.83.12.4431.

Tsai-Morris CH, Geng Y, Buczko E, Dehejia A, Dufau ML: Genomic distribution and gonadal mRNA expression of two human luteinizing hormone receptor exon 1 sequences in random populations. Hum Hered. 1999, 49: 48-51. 10.1159/000022840.

Chen ZJ, Zhao H, He L, Shi Y, Qin Y, Shi Y, Li Z, You L, Zhao J, Liu J, et al: Genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for polycystic ovary syndrome on chromosome 2p16.3, 2p21 and 9q33.3. Nat Genet. 2011, 43: 55-59. 10.1038/ng.732.

Kerkela E, Skottman H, Friden B, Bjuresten K, Kere J, Hovatta O: Exclusion of coding-region mutations in luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor genes as the cause of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2007, 87: 603-606. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.06.060.

Bergh PA, Navot D: Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: a review of pathophysiology. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1992, 9: 429-438. 10.1007/BF01204048.

Navot D, Bergh PA, Laufer N: Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in novel reproductive technologies: prevention and treatment. Fertil Steril. 1992, 58: 249-261.

Westfall PH, Wolfinger RD: Closed multiple testing procedures and PROC MULTTEST. 2000, Estados Unidos: Observations SAS Institute Inc.

Lancaster AK, Single RM, Solberg OD, Nelson MP, Thomson G: PyPop update–a software pipeline for large-scale multilocus population genomics. Tissue Antigens. 2007, 69 (Suppl 1): 192-197.

Gaunt TR, Rodriguez S, Day IN: Cubic exact solutions for the estimation of pairwise haplotype frequencies: implications for linkage disequilibrium analyses and a web tool ‘CubeX’. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007, 8: 428-10.1186/1471-2105-8-428.

Achrekar SK, Modi DN, Desai SK, Mangoli VS, Mangoli RV, Mahale SD: Follicle-stimulating hormone receptor polymorphism (Thr307Ala) is associated with variable ovarian response and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in Indian women. Fertil Steril. 2009, 91: 432-439. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.11.093.

d’Alva CB, Serafini P, Motta E, Kohek MB, Latronico AC, Mendonca BB: Absence of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor activating mutations in women with iatrogenic ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2005, 83: 1695-1699. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.12.044.

Moron FJ, De Castro F, Royo JL, Montoro L, Mira E, Saez ME, Real LM, Gonzalez A, Manes S, Ruiz A: Bone morphogenetic protein 15 (BMP15) alleles predict over-response to recombinant follicle stimulation hormone and iatrogenic ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2006, 16: 485-495. 10.1097/01.fpc.0000215073.44589.96.

Hanevik HI, Hilmarsen HT, Skjelbred CF, Tanbo T, Kahn JA: Increased risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome following controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in patients with vascular endothelial growth factor +405 cc genotype. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012, 28: 845-849. 10.3109/09513590.2012.683056.

Haasl RJ, Ahmadi MR, Meethal SV, Gleason CE, Johnson SC, Asthana S, Bowen RL, Atwood CS: A luteinizing hormone receptor intronic variant is significantly associated with decreased risk of Alzheimer’s disease in males carrying an apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele. BMC Med Genet. 2008, 9: 37-

Corbo RM, Ulizzi L, Scacchi R, Martinez-Labarga C, De Stefano GF: Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and fertility: a study in pre-industrial populations. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004, 10: 617-620. 10.1093/molehr/gah082.

Corbo RM, Ulizzi L, Piombo L, Scacchi R: Study on a possible effect of four longevity candidate genes (ACE, PON1, PPAR-gamma, and APOE) on human fertility. Biogerontology. 2008, 9: 317-323. 10.1007/s10522-008-9143-9.

Corbo RM, Scacchi R, Cresta M: Differential reproductive efficiency associated with common apolipoprotein e alleles in postreproductive-aged subjects. Fertil Steril. 2004, 81: 104-107. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.05.029.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jin Young Youn for technical assistance, Dr. Ewen Kirkness for technical assistance and Douglas Peak for help with patient recruitment and sample collection. We would also like to thank the many patients who participated in this study. None of the authors have financial conflicts of interest to report. The project described was supported by Award Number UL1RR031988 from the National Center for Research Resources (T.J.O). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests associated with this work.

Authors’ contributions

TO: Conceived of the study, participated in its design, carried out molecular analyses, assisted in data analysis and drafted the manuscript. MK: Conducted statistical analyses, assisted with drafting the manuscript. AH: Participated in study design, assisted in data analysis and drafted the manuscript. AC: Carried out molecular analysis with TO. IG: Processed samples, carried out molecular analysis with TO. SS: Worked with MK on all statistical analyses. DF: Conceived of the study, participated in its design, recruited participants, assisted with drafting the manuscript. PG: Conceived of the study, participated in its design, recruited participants, assisted with drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Brien, T.J., Kalmin, M.M., Harralson, A.F. et al. Association between the luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor (LHCGR) rs4073366 polymorphism and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 11, 71 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-11-71

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-11-71