Abstract

Background

Many patients with chronic illness are limited in their physical activities. This systematic review evaluates the content and format of patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaires that measure physical activity in elderly and chronically ill populations.

Methods

Questionnaires were identified by a systematic literature search of electronic databases (Medline, Embase, PsychINFO & CINAHL), hand searches (reference sections and PROQOLID database) and expert input. A qualitative analysis was conducted to assess the content and format of the questionnaires and a Venn diagram was produced to illustrate this. Each stage of the review process was conducted by at least two independent reviewers.

Results

104 questionnaires fulfilled our criteria. From these, 182 physical activity domains and 1965 items were extracted. Initial qualitative analysis of the domains found 11 categories. Further synthesis of the domains found 4 broad categories: 'physical activity related to general activities and mobility', 'physical activity related to activities of daily living', 'physical activity related to work, social or leisure time activities', and '(disease-specific) symptoms related to physical activity'. The Venn diagram showed that no questionnaires covered all 4 categories and that the '(disease-specific) symptoms related to physical activity' category was often not combined with the other categories.

Conclusions

A large number of questionnaires with a broad range of physical activity content were identified. Although the content could be broadly organised, there was no consensus on the content and format of physical activity PRO questionnaires in elderly and chronically ill populations. Nevertheless, this systematic review will help investigators to select a physical activity PRO questionnaire that best serves their research question and context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Many patients with chronic diseases experience physical activity limitations or suffer symptoms during physical activities. This is concerning given the wealth of evidence demonstrating the importance of a physically active lifestyle in the prevention and management of many chronic diseases [1, 2]. Physical activity has been defined as 'any bodily movement produced by the contraction of skeletal muscle that increases energy expenditure above a basal level' [3]. It is useful as an outcome measurement as it enables researchers to effectively evaluate public health interventions to increase physical activity levels. It is also currently being explored as an endpoint for evaluating the efficacy of pharmaceutical interventions in clinical trials. This could help inform patients about treatment options that may improve their daily life.

When deciding to assess physical activity as an outcome measure, researchers face the challenge of selecting from a myriad of objective and subjective assessments. For subjective assessments, a large number of patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaires are available to choose from. PRO questionnaires are self-report measures of a patient's health status or behaviour that comes directly from the patient without interpretation from anyone else. Such questionnaires have the potential to capture patient-relevant lifestyle physical activities and related limitations that may not be identified by more objective assessments. For this reason, it is important that the content of physical activity PRO questionnaires is relevant to the patient in order to make appropriate, patient centred treatment choices [4, 5]. In addition, the format of the questionnaire should be such that the questions and answer options can be easily interpreted and completed by the patient.

Although there have been several reviews of physical activity PRO questionnaires in recent years (e.g. [6]), the majority of these have focused on the development and validation processes. To our knowledge, no review to date has specifically focused in depth on content and format such as looking at themes and patterns across questionnaires.

This review is part of the European Union funded PROactive project [7] which aims to develop and validate a PRO tool to investigate dimensions of physical activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. The initial aim of this review was therefore to identify existing physical activity PRO questionnaires which are appropriate for use in a COPD population. Although we were primarily interested in questionnaires developed for COPD patients, we were also interested in learning from questionnaires developed for elderly populations or patients with other chronic diseases that may result in physical activity limitations. The second aim was to systematically evaluate these questionnaires with the aim of establishing if there is a consensus on their optimal content and format (the development and psychometric properties are explored in a separate paper [8]). These results may help researchers to select the most appropriate physical activity PRO questionnaires available to date, and will identify research gaps.

Methods

A study protocol (unregistered) guided the entire review process. We followed standard systematic review methodology as outlined in the handbooks of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination [9] and the Cochrane Collaboration. The reporting follows the PRISMA statement guidelines for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses [10].

Eligibility criteria

Population

As this systematic review is part of the PROactive project [7], we were interested in identifying physical activity PRO questionnaires that are appropriate for use in a COPD population. We therefore supplemented the electronic database search with explicit search terms for COPD patients. However, we were also interested in learning from the content and format of questionnaires developed for other disease populations which may experience similar physical activity limitations to COPD patients. We therefore expanded our search to include PRO questionnaires developed for patients with all chronic illnesses and elderly populations.

Style of questionnaire

We included fully structured questionnaires or scales with standardised questions and answer options which were patient (self) reported. Interviewer administered questionnaires were included only if the information was self-reported. Questionnaires that required a rating by an interviewer were excluded.

Assessment of physical activity

We included questionnaires containing at least one physical activity subscale/domain. We used this benchmark as the number of questionnaires containing only one or two physical activity items was too large to include in this review. The PROactive consortium agreed to use the following definition for physical activity by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [3]: 'any bodily movement produced by the contraction of skeletal muscle that increases energy expenditure above a basal level'. In addition to questionnaires measuring the frequency, intensity and total amount of physical activity, we also considered questionnaires assessing 'related constructs' such as symptoms (physical and mental) or limitations associated with physical activity. We only included questionnaires if the items were available from the publication or developers. We did not have any language or publication date restrictions.

Study design

We included cross-sectional and longitudinal studies that described the development or modifications of the original questionnaire and/or the initial validation of the original questionnaire. We excluded studies that were not designed to initially validate a questionnaire, for example, those that reported linguistic validation or used a questionnaire as an outcome measure in a clinical trial or observational study.

Information sources

Electronic database searches

We searched the electronic databases Medline, Embase, PsycINFO and CINAHL on September 18th 2009.

Hand searches

In addition to the electronic database search, we did the following hand searches: we searched for original development studies of questionnaires from articles which were excluded for the reason 'validation only' or 'used as outcome measures'; we scanned the reference lists of the full texts; we searched for 'physical functioning' questionnaires in the Patient-Reported Outcome and Quality of Life Questionnaires Database (PROQOLID) on March 10 2010; and we contacted experts in the field (the PROactive research consortium and associated expert panel) to check that our list was complete.

Search

We searched the electronic databases using the following search terms: (physical activity OR functioning OR function OR motor activity OR activities of daily living OR walking OR activity OR exercise) AND (questionnaire* OR scale OR tool OR diary OR assessment OR self-report OR measure*) AND (valid*) AND (chronic disease OR elderly OR COPD OR chronic lung disease OR chronic obstructive lung disease) NOT (athletic performance OR sports OR children OR adolescent).

Study selection

The study selection process was piloted by at least two independent reviewers at the start of the review. All titles and abstracts were screened and the decision to include or exclude was recorded (0 = exclude, 1 = order for full text assessment, 2 = only validation study of existing questionnaire, 3 = related study (e.g. reviews), do not order but may be useful reference). All articles that were deemed potentially eligible by at least one reviewer proceeded to full text review. The full texts were then scored against the predefined selection criteria and the decision to include or exclude was again recorded. If there was a discrepancy between two reviewers, a third reviewer was consulted. If the article contained insufficient information then we made three attempts to contact the authors and recorded the outcome. In cases where multiple papers were published (e.g. translations, reporting on different outcomes etc.), we treated the multiple reports as a single study but made reference to all publications.

Data extraction process

We created standardised data extraction forms to record the relevant information from the articles. The data extraction forms were piloted twice by four reviewers. The forms and categories were then adapted and refined where necessary. The first reviewers extracted the data and stored it in a MS Word file. The second reviewers then independently extracted the data and compared their results with that of the first reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by consulting a third independent reviewer.

Data extraction

We extracted data on the questionnaires' content and format. The format categories were: population (elderly or type of chronic disease), answer options (e.g. 5-point Likert scale, categorical scales), anchors (e.g. 0 = not limited at all to 6 = totally limited), scoring (e.g. total score or average), direction of scale (uni- or bi-directional), recall period (e.g. past 24 hours or past week), administration (self or interviewer administered), quantification (whether questionnaires quantified the amount of physical activity [e.g. number of hours spent] or not), and type of questionnaire (quick overview of the method of assessment [e.g. ability, frequency], the content of assessment [e.g. breathlessness] and the population). The content categories were: a general description of the questionnaire (physical activity only or general questionnaire with physical activity subscales), number of items, number of domains, and labelling of domains.

Content analysis

Content analysis of the domain labels was conducted to synthesise the data. The domains were independently grouped into broad categories by two reviewers and their level of agreement was calculated using Cohen's Kappa coefficient. Mismatches were then resolved and a third reviewer was consulted where necessary. Once the categorisation of all the domains had been agreed, the frequency of domains per category was calculated. Following the categorisation of domains into broad categories, a second content analysis was conducted to further synthesise the content of the questionnaires. This was again done by two independent reviewers and a third reviewer was consulted where necessary. A Venn diagram was then produced to give a visual representation of the content of the questionnaires. A brief content analysis was also conducted for the populations for which the questionnaires were developed (focusing on COPD and related respiratory diseases) and the answer options used.

Results

Study selection

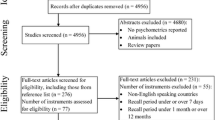

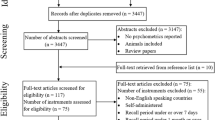

Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the study identification process. The electronic database search produced 2542 references. After title and abstract screening, 2268 of these were excluded resulting in 274 for full text assessment. This included 5 Japanese and 1 Chinese article which were provisionally included due to their English abstract but were not included in the current analysis as we were unable to translate them [11–15]. Hand searches of reference sections and of excluded articles revealed an additional 70 questionnaires/development studies for full text assessment. The search of the PROQOLID database produced a further 58 questionnaires, 19 of which were included for full text assessment after title and abstract screening. One additional questionnaire was retrieved from the consultation with experts. Therefore, a total of 364 papers were included for full text assessment.

Following full text assessment, a further 255 articles were excluded resulting in 104 questionnaires from 103 full texts included in the review [16–119] (one article [65] provided information for the development process of two questionnaires). The most frequent reasons for exclusion were: the questionnaire is not self-reported (n = 71), the questionnaire does not measure physical activity (defined as above [3]) (n = 66), the article was a validation study only (other than the original validation) (n = 35) and the article used the questionnaire as an outcome measure only (did not describe the development or initial validation) (n = 29). The references of all articles excluded after full text assessment are summarised in Additional file 1.

Content of questionnaires

Additional file 2 summarises the extracted data on the content and format of the reviewed questionnaires.

Fifty nine (56.7%) questionnaires focused on physical activity only. Forty three (41.3%) did not focus on physical activity but contained at least one physical activity subscale. Two (1.9%) questionnaires [78, 118] were not described in the publication and the questionnaires were not available from the authors.

A total of 1965 items (a further 5 questionnaires did not report the number of items) relating to physical activity were extracted. The items were not checked for duplicates due to their large number; however, it is unlikely that the items with exactly the same wording would have appeared multiple times. The number of physical activity items per questionnaire ranged from 3 to 123.

After the removal of 56 duplicate domains, a total of 182 physical activity domains (a further 2 articles did not report their domains) were extracted. The number of physical activity domains per questionnaire ranged from 1 to 12. The domains that appeared multiple times are shown in Table 1. All other domains appeared only once.

The initial thematic analysis of the 182 physical activity domains found 11 broad categories, plus an additional 'other' category (defined in Table 2). The inter-rater reliability of the initial independent coding of the 182 domains was high with a Cohen's Kappa of 0.87 (p < 0.001) and 88.5% total accordance. After agreement for mismatches, the number of the domains per content theme were: physical activity related mobility (n = 34), household physical activity (n = 21), generic physical activity (n = 20), social physical activity (n = 18), physical activity relating to self (n = 17), dyspnoea & symptom related physical activity (n = 12), leisure physical activity (n = 9), work physical activity (n = 9), exercise physical activity (n = 10), physical activity limitations (n = 8), activities of daily living (ADL) (n = 7) and other (n = 17). The full list of domains and their 11 categories are shown in Additional file 2.

The second content analysis resulted in 4 categories plus an additional 'other' category (defined in Table 3). The Venn diagram in Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of the questionnaires across these 4 categories. This shows that 59 questionnaires contained the domain 'physical activity related to general activities and mobility', 39 the domain 'physical activity related to activities of daily living', 32 the domain 'physical activity related to work, social or leisure time activities', and 18 the domain '(disease-specific) symptoms related to physical activity'. The Venn diagram also shows that none of the questionnaires contained domains from all 4 of the categories. Further, questionnaires containing '(disease-specific) symptoms related to physical activity' domains did not often contain domains from the other 3 categories as well.

Format of questionnaires

The questionnaires were developed for patients with a range of chronic diseases and elderly populations. These populations were grouped into the 5 categories 'Elderly', 'COPD patients', 'Patients with other chronic respiratory diseases', 'Patients with unspecified chronic disease or disability', and 'Patients with other specified chronic diseases' (Table 4).

Analysis of the 1965 items revealed 12 different types of answer option (Table 5) and 209 different anchors (duplicate anchors removed). The full list can be seen in Additional file 2. Of the 209 different anchors, the most frequent was the categorical yes/no scale which was used for 265 items overall.

Sixty eight (65.4%) questionnaires were scored by calculating the sum of the items to domains scores and total scores, 10 (9.6%) by calculating a mean score of completed items, 5 (4.8%) using Guttman scaling and 6 (5.8%) using another method classified as 'other'. Fifteen (14.4%) questionnaires did not report the method of scoring used.

Seventy three (70.2%) questionnaires were uni-directional, meaning that the items were phrased in the same direction, either positively or negatively. Three questionnaires (2.9%) were bi-directional, 1 (1%) contained uni-directional and bi-directional items and 27 (26%) did not report the scale direction or direction was not applicable (e.g. categorical scales).

Forty two different recall periods were identified and these were grouped thematically into 10 categories plus a 'not reported/unclear' category. Table 6 shows the categories along with the number of questionnaires to which they apply.

Fifty eight (55.8%) questionnaires were self-administered, 25 (24%) were interviewer-administered and 16 (15.4%) were either self- or interviewer-administered. Five (4.8%) questionnaires did not report their administration format.

Nine of the questionnaires quantified the amount of physical activity engaged in (e.g. total time, duration), whereas the other 95 did not. These questionnaires can be seen in row 3 of Table 7.

We identified 8 types of questionnaire based on their method of assessing physical activity (e.g. ability) and the content of this assessment (e.g. limitations). These types, along with the frequency of questionnaire for each type and the reference numbers of the questionnaires for each type are shown in Table 7.

Discussion

This systematic review found many PRO questionnaires for assessing physical activity. Most questionnaires focused on physical activity alone (see definition [3]) but there were also multiple questionnaires containing physical activity domains or subscales. Most questionnaires were developed for patients with chronic diseases, although the single largest group was elderly. The format of the questionnaires including the answer options, anchors and recall periods varied considerably. The most common answer option was the yes/no scale. Most questionnaires had no recall period, were uni-directional, self-administered and scored by calculating the sum of the domain or total scores.

Multiple domains and items were extracted and although the domains were grouped broadly into 11 categories, the content varied considerably. Further synthesis into 4 categories and the Venn diagram revealed that no questionnaires contained domains from all 4 categories. This was surprising as we expected to see increased overlap due to the large number of domains and the small number of categories. However, we acknowledge that the questionnaires were developed for a range of populations and limitations experienced by some groups may not be universal. The Venn diagram also showed that '(disease-specific) symptoms related to physical activity' were included by the fewest questionnaires and infrequently overlapped with the other categories. This shows that symptoms and limitations related to physical activity are not prominent in the currently available PRO questionnaires. This is concerning as qualitative research has shown that patients with certain chronic conditions (e.g. asthma) consider symptoms in association with physical activity to be very relevant [120]. This inconsistency may be due to inadequate patient input in the development of these questionnaires as was found in the first part of this review [8]. However, we acknowledge that symptoms are not a relevant aspect of all chronic conditions (e.g. hypertension).

Overall the results show that there is no consensus on what should be included in the content and format of physical activity PRO questionnaires. This is in line with previous reviews which have found variation in the number of recall periods used [6] and inconsistencies in the development and validation methods questionnaires [6, 8]. The lack of consensus may also arise from the scarcity of conceptual frameworks for physical activity, which was documented recently [121]. This highlights a need for further research into physical activity and its potential use as an outcome measure to evaluate treatment benefit. In addition, the results show that many physical activity questionnaires lack important concepts, particularly those relating to symptoms and limitations with physical activity. This poses a problem to researchers when deciding which physical activity PRO questionnaire to choose for their purpose as no questionnaire measures all aspects of physical activity. Although this highlights a need for patient input in the development of future physical activity questionnaires, it is also important to acknowledge that physical activity is a multidimensional construct. It is therefore challenging to create a single questionnaire which encompasses all aspects.

Nevertheless, both this review and our previous systematic review [8] provide a broad overview of physical activity questionnaires and can be used to guide researchers in their selection a questionnaire. For example, a questionnaire may be needed to assess physical activity as an outcome in a pulmonary rehabilitation intervention study of COPD patients (example 1). As another example, investigators may need a questionnaire to assess the association between physical activity and mortality in a prospective cohort study of elderly people (example 2). In situations like these, Additional file 2 will be a useful tool for researchers as it summarises the content and format of the large variety of available questionnaires.

To evaluate pulmonary rehabilitation (as in example 1), a suitable questionnaire may be one that was specifically developed for COPD patients (see 'Population' in Additional file 2) and that assesses domains that a pulmonary rehabilitation program aims to improve (e.g. the patients' ability to perform activities of daily living, see 'Questionnaire type'). Even more specifically, investigators could choose between different types of activities of daily living or household physical activities (see 'Category' and 'Labelling of domains'). Since a study on pulmonary rehabilitation is typically designed to detect a change over time, a unidirectional Likert type scale would be reasonable, encompassing at least 5 points, with corresponding anchors (see 'Direction of scale', 'Answer options' and 'Anchors') resulting in different domain and total scores (see 'Scoring'). Depending on the number of other assessments they may be using, investigators may also want to consider the time to complete ('Number of items') and the recall period ('Recall period') in order to minimise information bias. Based on these considerations, the London Chest Activity of Daily Living Scale [49] or the Activity of Daily Living Dyspnoea scale [115] would be reasonable choices.

If physical activity is measured as a determinant of mortality (as in example 2), the amount of physical activity ('Quantification', 'Questionnaire type') is likely to be of importance (e.g. [122]) and could be expressed by the frequency and time spent for performing certain activities ('Category', 'Labelling of domains'). A single number representing the amount of physical activity ('Scoring') would be attractive from a statistical and interpretative perspective. Also, as the researcher may be assessing other determinants of mortality, the length of the questionnaire should be considered to avoid patient burden ('Number of items'). An appropriate questionnaire for this example would be the YALE Physical Activity Survey [36].

During the selection process, the measurement properties also need to be considered once potential questionnaires have been identified based on content and format requirements. For an overview of the development and initial validation data of the questionnaires, readers are referred to Additional file 2 in our previous publication [8].

One of the strengths of this review is that we adhered to a rigorous systematic review methodology throughout the process. We used carefully developed inclusion and exclusion criteria and each step was conducted by at least two independent reviewers from at least two independent institutions to ensure that the most appropriate physical activity questionnaires were included. We kept our search strategy deliberately broad to avoid missing any potentially relevant questionnaires, resulting in what is likely to be the most comprehensive systematic review of physical activity questionnaires to date. We did this by using the definition for physical activity as described in the 2008 physical activity guidelines for Americans [3] as a guide. In addition to public database searches we added a thorough hand search of reference sections and the PROQOLID database, resulting in an extensive domain and item pool of physical activity questionnaires.

A challenge of this review was dealing with situations where the decision to include or exclude a questionnaire was unclear. Although we followed carefully defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, some questionnaires assessed specific types of physical activity that were largely unique to the population for which they were developed. In such cases we attempted to make a judgement to include or exclude that was systematically and scientifically defendable. For example, if a questionnaire had been developed for multiple sclerosis patients, we excluded physical activity domains that assessed impaired hand motor activity, but included general domains such as 'walking ability' [55] or 'physical functioning' [95]. Furthermore, although we did not analyse the content of the individual items, they were all entered into an item pool which can be utilised during the later stages of the PROactive project and will be made available to the public upon the conclusion of the project.

Conclusions

This review found a large number of PRO questionnaires are available for assessing physical activity in elderly and chronically ill populations. From these, 182 different physical activity domains were identified. Although the content could be broadly organised, there was little consensus on the content and format of physical activity PRO questionnaires in these populations. Nevertheless, this systematic review will help investigators to select a physical activity PRO questionnaire that best serves their research question and context.

Authors' information

KR is an honorary lecturer of health psychology at the University of Kent, UK. Fabienne Dobbels is a post-doctoral researcher funded by the FWO (Scientific Research Foundation Flanders).

Acknowledgements

The study was conducted within the PROactive project which is funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking (IMI JU) # 115011. The authors would also like to thank Laura Jacobs for her support in the early stages of the project as well as the PROactive group: Caterina Brindicci and Tim Higenbottam (Chiesi Farmaceutici S.A.), Thierry Trooster and Fabienne Dobbels (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven), Margaret X. Tabberer (Glaxo Smith Kline), Roberto Rabinovitch and Bill McNee (University of Edinburgh, Old College South Bridge), Ioannis Vogiatzis (Thorax Research Foundation, Athens), Michael Polkey and Nick Hopkinson (Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust), Judith Garcia-Aymerich (Municipal Institute of Medical Research, Barcelona), Milo Puhan and Anja Frei (Universität of Zürich, Zürich), Thys van der Molen and Corina De Jong (University Medical Center, Groningen), Pim de Boer (Netherlands Asthma Foundation, Leusden), Ian Jarrod (British Lung Foundation, UK), Paul McBride (Choice Healthcare Solution, UK), Nadia Kamel (European Respiratory Society, Lausanne), Katja Rudell and Frederick J. Wilson (Pfizer Ltd), Nathalie Ivanoff (Almirall), Karoly Kulich and Alistair Glendenning (Novartis), Niklas X. Karlsson and Solange Corriol-Rohou (AstraZeneca AB), Enkeleida Nikai (UCB) and Damijen Erzen (Boehringer Ingelheim).

Abbreviations

- PRO:

-

Patient-reported outcome

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- IADL:

-

Instrumental activities of daily living.

References

Lagerros YT, Lagiou P: Assessment of physical activity and energy expenditure in epidemiological research of chronic diseases. Eur J Epidemiol 2007, 22(6):353–362.

Valanou EM, Bamia C, Trichopoulou A: Methodology of physical-activity and energy-expenditure assessment: A review. J Public Health 2006, 14(2):58–65.

2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans[http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/pdf/paguide.pdf]

Bottomley A, Jones D, Claassens L: Patient-reported outcomes: Assessment and current perspectives of the guidelines of the Food and Drug Administration and the reflection paper of the European Medicines Agency. Eur J Cancer 2009, 45(3):347–353.

European Medicines Agency (EMA): CHMP Reflection Paper on the Regulatory Guidance for the Use of Health Related Quality of life Measures in the Evaluation of Medicinal Products.2006. [http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003637.pdf]

Forsen LLN, Vuillemin A, Chinapaw MJM, van Poppel MNM, Mokkink LB, van Mechelen W, Terwee CB: Self-administered physical activity q. Sports Med 2010, 40: 601–623.

PROactive[http://www.proactivecopd.com/]

Frei A, Williams K, Vetsch A, Dobbels F, Jacobs L, Rudell K, Puhan MA: A comprehensive systematic review of the development process of 104 patient-reported outcomes (PROs) for physical activity in chronically ill and elderly people. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011, 9(1):116..

Systematic Reviews. CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York; 2009.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339: 332–336.

ChongHua W, Li G, XiaoMei L: Development of the General Module for the System of Quality of Life Instruments for Patients with Chronic Disease: Items selection and structure of the general module. Chinese Mental Health Journal 2005, 19(11):723–726.

Eto F, Tanaka M, Chishima M, Igarashi M, Mizoguchi T, Wada H, Iijima S: Comprehensive activities of daily living (ADL) index for the elderly. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi - Japanese Journal of Geriatrics 1992, 29(11):841–848.

Hashimoto S, Aoki R, Tamakoshi A, Shibazaki S, Nagai M, Kawakami N, Ikari A, Ojima T, Ohno Y: Development of index of social activities for the elderly. Nippon Koshu Eisei Zasshi - Japanese Journal of Public Health 1997, 44(10):760–768.

Horiuchi T, Kobayashi Y, Hosoi T, Ishibashi H, Yamamoto S, Yatomi N: The assessment of the reliability and the validity of the EOQOL questionnaire of osteoporotics-QOL assessment of elderly osteoporotics by EOQOL. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi - Japanese Journal of Geriatrics 2005, 42(2):229–234.

Inaba Y, Obuchi S, Oka K, Arai T, Nagasawa H, Shiba Y, Kojima M: Development of a rating scale for self-efficacy of physical activity in frail elderly people. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi - Japanese Journal of Geriatrics 2006, 43(6):761–768.

Alvarez-Gutierrez FJ, Miravitlles M, Calle M, Gobartt E, Lopez F, Martin A, Grupo de Estudio EIME: Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on activities of daily living: results of the EIME multicenter study. Arch Bronconeumol 2007, 43(2):64–72.

Anagnostis C, Gatchel RJ, Mayer TG: The pain disability questionnaire: a new psychometrically sound measure for chronic musculoskeletal disorders. Spine 2004, 29(20):2290–2302.

Anderson KO, Dowds BN, Pelletz RE, Edwards WT, Peeters-Asdourian C: Development and initial validation of a scale to measure self-efficacy beliefs in patients with chronic pain. Pain 1995, 63(1):77–84.

Arbuckle TY, Gold DP, Chaikelson JS, Lapidus S: Measurement of activity in the elderly: The Activities Checklist. Can J Aging 1994, 13(4):550–565.

Avlund K, Kreiner S, Schultz-Larsen K: Functional ability scales for the elderly: a validation study. Eur J Public Health 1996, 6(1):35–42.

Avlund K, Schultz-Larsen K, Kreiner S: The measurement of instrumental ADL: content validity and construct validity. Aging Clin Exp Res 1993, 5(5):371–383.

Baiardini I, Braido F, Fassio O, Tarantini F, Pasquali M, Tarchino F, Berlendis A, Canonica GW: A new tool to assess and monitor the burden of chronic cough on quality of life: Chronic Cough Impact Questionnaire. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2005, 60(4):482.

Bergner MPD, Bobbitt RAPD, Carter WBPD, Gilson BSMD: The Sickness Impact Profile: Development and Final Revision of a Health Status Measure. Medical care 1981, 19(8):787–805.

Bula CJ, Martin E, Rochat S, Piot-Ziegler C: Validation of an adapted falls efficacy scale in older rehabilitation patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008, 89(2):291–296.

Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM: The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire: development and validation. J Rheumatol 1991, 18(5):728–733.

Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, Kennedy LG, O'Hea J, Mallorie P, Jenkinson T: A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol 1994, 21(12):2281–2285.

Cardol M, de Haan RJ, de Jong BA, van den Bos GA, de Groot IJ: Psychometric properties of the Impact on Participation and Autonomy Questionnaire. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001, 82(2):210–216.

Cardol M, de Haan RJ, van den Bos GA, de Jong BA, de Groot IJ: The development of a handicap assessment questionnaire: the Impact on Participation and Autonomy (IPA). Clin Rehabil 1999, 13(5):411–419.

Carone M, Bertolotti G, Anchisi F, Zotti AM, Donner CF, Jones PW: Analysis of factors that characterize health impairment in patients with chronic respiratory failure Quality of Life in Chronic Respiratory Failure Group. Eur Respir J 1999, 13(6):1293–1300.

Caspersen CJ, Bloemberg BPM, Saris WHM, Merritt RK, Kromhout D: The Prevalence of Selected Physical Activities and Their Relation with Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factors in Elderly Men: The Zutphen Study, 1985. Am J Epidemiol 1991, 133(11):1078–1092.

Chou K: Hong Kong Chinese Everyday Competence Scale: a validation study. Clin Gerontol 2003, 26(1):43–51.

Clark DO, Callahan CM, Counsell SR: Reliability and validity of a steadiness score. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005, 53(9):1582–1586.

Clark MS, Bond MJ: The Adelaide Activities Profile: a measure of the life-style activities of elderly people. Aging Clin Exp Res 1995, 7(4):174–184.

Dallosso HM, Morgan K, Bassey EJ, Ebrahim SB, Fentem PH, Arie TH: Levels of customary physical activity among the old and the very old living at home. J Epidemiol Community Health 1988, 42(2):121–127.

Davis AH, Figueredo AJ, Fahy BF, Rawiworrakul T: Reliability and validity of the Exercise Self-Regulatory Efficacy Scale for individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung 2007, 36(3):205–216.

Dipietro L, Caspersen CJ, Ostfeld AM, Nadel ER: A survey for assessing physical activity among older adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 1993, 25(5):628–642.

Dorevitch MI, Cossar RM, Bailey FJ, Bisset T, Lewis SJ, Wise LA, MacLennan WJ: The accuracy of self and informant ratings of physical functional capacity in the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 1992, 45(7):791–798.

Dunderdale K, Thompson DR, Beer SF, Furze G, Miles JNV: Development and validation of a patient-centered health-related quality-of-life measure: the Chronic Heart Failure Assessment Tool. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2008, 23(4):364–370.

Eakin EG, Resnikoff PM, Prewitt LM, Ries AL, Kaplan RM: Validation of a new dyspnea measure: the UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire. Chest 1998, 113(3):619–624.

Eakman AM: A reliability and validity study of the Meaningful Activity Participation Assessment. University of Southern California; 2007.

Fillenbaum GG: Screening the elderly. A brief instrumental activities of daily living measure. J Am Geriatr Soc 1985, 33(10):698–706.

Fillenbaum GG, Smyer MA: The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire. J Gerontol 1981, 36(4):428–434.

Finch M, Kane RL, Philp I: Developing a new metric for ADLs. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995, 43(8):877–884.

Follick MJ, Ahern DK, Laser-Wolston N: Evaluation of a daily activity diary for chronic pain patients. Pain 1984, 19(4):373–382.

Frederiks CM, te Wierik MJ, Visser AP, Sturmans F: The functional status and utilization of care of elderly people living at home. J Community Health 1990, 15(5):307–317.

Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Bryant HE: The lifetime total physical activity questionnaire: development and reliability. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 1998, 30(2):266–274.

Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY: The dimensions of health outcomes: the health assessment questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheumatol 1982, 9(5):789–793.

Garrad J, Bennett AE: A validated interview schedule for use in population surveys of chronic disease and disability. Br J Prev Soc Med 1971, 25(2):97–104.

Garrod R, Bestall JC, Paul EA, Wedzicha JA, Jones PW: Development and validation of a standardized measure of activity of daily living in patients with severe COPD: the London Chest Activity of Daily Living scale (LCADL). Respir Med 2000, 94(6):589–596.

Guyatt GH, Berman LB, Townsend M, Pugsley SO, Chambers LW: A measure of quality of life for clinical trials in chronic lung disease. Thorax 1987, 42(10):773–778.

Guyatt GH, Eagle DJ, Sackett B, Willan A, Griffith L, McIlroy W, Patterson CJ, Turpie I: Measuring quality of life in the frail elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 1993, 46(12):1433–1444.

Harwood RH, Rogers A, Dickinson E, Ebrahim S: Measuring handicap: the London Handicap Scale, a new outcome measure for chronic disease. Qual Health Care 1994, 3(1):11–16.

Helmes E, Hodsman A, Lazowski D, Bhardwaj A, Crilly R, Nichol P, Drost D, Vanderburgh L, Pederson L: A Questionnaire To Evaluate Disability in Osteoporotic Patients With Vertebral Compression Fractures. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 1995, 50A(2):M91-M98.

Hlatky MA, Boineau RE, Higginbotham MB, Lee KL, Mark DB, Califf RM, Cobb FR, Pryor DB: A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (the Duke Activity Status Index). Am J Cardiol 1989, 64(10):651–654.

Hobart JC, Riazi A, Lamping DL, Fitzpatrick R, Thompson AJ: Measuring the impact of MS on walking ability: The 12-Item MS Walking Scale (MSWS-12). Neurology 2003, 60(1):31–36.

Holbrook M, Skilbeck CE: An activities index for use with stroke patients. Age Ageing 1983, 12(2):166–170.

Hyland ME: The Living with Asthma Questionnaire. Respir Med 1991, 85(2):13–16.

Jacobs JE, Maille AR, Akkermans RP, van Weel C, Grol RP: Assessing the quality of life of adults with chronic respiratory diseases in routine primary care: construction and first validation of the 10-Item Respiratory Illness Questionnaire-monitoring 10 (RIQ-MON10). Qual Life Res 2004, 13(6):1117–1127.

Jette AM, Deniston OL: Inter-observer reliability of a functional status assessment instrument. J Chronic Dis 1978, 31(9–10):573–580.

Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P: A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992., 145(6):

Kaplan RM, Sieber WJ, Ganiats TG: The quality of well-being scale: comparison of the interviewer-administered version with a self-administered questionnaire. Psychol Health 1997, 12: 783–791.

Keith RA, Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Sherwin FS: The functional independence measure: a new tool for rehabilitation. Adv Clin Rehabil 1987, 1: 6–18.

Kempen GI, Suurmeijer TP: The development of a hierarchical polychotomous ADL-IADL scale for noninstitutionalized elders. Gerontologist 1990, 30(4):497–502.

Kuhl K, Schurmann W, Rief W: COPD disability index (CDI) - a new instrument to assess COPD-related disability. COPD-Disability-Index (CDI) - ein neues Verfahren zur Erfassung der COPD-bedingten Beeintrachtigung 2009, 63(3):136.

Mannerkorpi K, Hernelid C: Leisure Time Physical Activity Instrument and Physical Activity at Home and Work Instrument. Development, face validity, construct validity and test-retest reliability for subjects with fibromyalgia. Disabil Rehabil 2005, 27(12):695–701.

Lareau SC, Carrieri-Kohlman V, Janson-Bjerklie S, Roos PJ: Development and testing of the Pulmonary Functional Status and Dyspnea Questionnaire (PFSDQ). Heart Lung 1994, 23(3):242–250.

Lareau SC, Meek PM, Roos PJ: Development and testing of the modified version of the Pulmonary Functional Status and Dyspnea Questionnaire (PFSDQ-M). Heart Lung 1998, 27(3):159–168.

Lee L, Friesen M, Lambert IR, Loudon RG: Evaluation of Dyspnea During Physical and Speech Activities in Patients With Pulmonary Diseases. Chest 1998, 113(3):625–632.

Leidy NK: Psychometric properties of the functional performance inventory in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nurs Res 1999, 48(1):20–28.

Lerner D, Amick BC III, Rogers WH, Malspeis S, Bungay K, Cynn D: The Work Limitations Questionnaire. Medical care 2001, 39(1):72–85.

Letrait M, Lurie A, Bean K, Mesbah M, Venot A, Strauch G, Grandordy BM, Chwalow J: The Asthma Impact Record (AIR) index: a rating scale to evaluate the quality of life of asthmatic patients in France. Eur Respir J 1996, 9(6):1167–1173.

Lewin RJ, Thompson DR, Martin CR, Stuckey N, Devlen J, Michaelson S, Maguire P: Validation of the Cardiovascular Limitations and Symptoms Profile (CLASP) in chronic stable angina. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2002, 22(3):184–191.

Linton SJ: Activities of daily living scale for patients with chronic pain. Percept Mot Skills 1990, 71(3 Pt 1):722.

Liu B, Woo J, Tang N, Ng K, Ip R, Yu A: Assessment of total energy expenditure in a Chinese population by a physical activity questionnaire: examination of validity. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2001, 52(3):269–282.

Maillé AR, Koning CJM, Zwinderman AH, Willems LNA, Dijkman JH, Kaptein AA: The development of the [']Quality-of-Life for Respiratory Illness Questionnaire (QOL-RIQ)': a disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for patients with mild to moderate chronic non-specific lung disease. Respir Med 1997, 91(5):297–309.

Mathias SD, Bussel JB, George JN, McMillan R, Okano GJ, Nichol JL: A disease-specific measure of health-related quality of life in adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura: psychometric testing in an open-label clinical trial. Clin Ther 2007, 29(5):950–962.

Mathuranath PS, George A, Cherian PJ, Mathew R, Sarma PS: Instrumental activities of daily living scale for dementia screening in elderly people. Int Psychogeriatr 2005, 17(3):461–474.

Mayer J, Mooney V, Matheson L, Leggett S, Verna J, Balourdas G, DeFilippo G: Reliability and validity of a new computer-administered pictorial activity and task sort. J Occup Rehabil 2005, 15(2):203–213.

McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Medical care 1994, 32(1):40–66.

Migliore Norweg A, Whiteson J, Demetis S, Rey M: A new functional status outcome measure of dyspnea and anxiety for adults with lung disease: the dyspnea management questionnaire. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2006, 26(6):395–404.

Moriarty D, Zack M, Kobau R: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Healthy Days Measures - Population tracking of perceived physical and mental health over time. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003, 1(1):37.

Morimoto M, Takai K, Nakajima K, Kagawa K: Development of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease activity rating scale: reliability, validity and factorial structure. Nurs Health Sci 2003, 5(1):23–30.

Morris WW, Buckwalter KC, Cleary TA, Gilmer JS: Issues related to the validation of the Iowa Self-Assessment Inventory. Educ Psychol Meas 1989, 49(4):853–861.

Myers J, Do D, Herbert W, Ribisl P, Froelicher VF: A nomogram to predict exercise capacity from a specific activity questionnaire and clinical data. Am J Cardiol 1994, 73(8):591–596.

Nijs J, Vaes P, McGregor N, Van Hoof E, De Meirleir K: Psychometric properties of the Dutch Chronic Fatigue Syndrome-Activities and Participation Questionnaire (CFS-APQ). Phys Ther 2003, 83(5):444–454.

Nouri FM, Lincoln NB: An extended activities of daily living scale for stroke patients. Clin Rehabil 1987, 1(4):301–305.

Parkerson GRJMDMPH, Gehlbach SHMDMPH, Wagner EHMDMPH, James SAPD, Clapp NERNMPH, Muhlbaier LHMS: The Duke-UNC Health Profile: An Adult Health Status Instrument for Primary Care. Medical care 1981, 19(8):806–828.

Pluijm SM, Bardage C, Nikula S, Blumstein T, Jylha M, Minicuci N, Zunzunegui MV, Pedersen NL, Deeg DJ: A harmonized measure of activities of daily living was a reliable and valid instrument for comparing disability in older people across countries. J Clin Epidemiol 2005, 58(10):1015–1023.

Rankin SL, Briffa TG, Morton AR, Hung J: A specific activity questionnaire to measure the functional capacity of cardiac patients. Am J Cardiol 1996, 77(14):1220–1223.

Regensteiner JG, Steiner JF, Panzer RJ, Hiatt WR: Evaluation of walking impairment by questionnaire in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Med Biol 1990, 2: 142–152.

Rejeski WJ, Ettinger JWH, Schumaker S, James P, Burns R, Elam JT: Assessing performance-related disability in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1995, 3(3):157–167.

Resnick B, Jenkins LS: Testing the reliability and validity of the Self-Efficacy for Exercise Scale. Nurs Res 2000, 49(3):154–159.

Rimmer JH, Riley BB, Rubin SS: A new measure for assessing the physical activity behaviors of persons with disabilities and chronic health conditions: the Physical Activity and Disability Survey. Am J Health Promot 2001, 16(1):34–42.

Roland M, Morris R: A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine 1983, 8(2):141–144.

Rotstein Z, Barak Y, Noy S, Achiron A: Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: development and validation of the 'RAYS' scale and comparison with the SF-36. Int J Qual Health Care 2000, 12(6):511–517.

Schag AC, Heinrich RL, Aadland RL, Ganz PA: Assessing Problems of Cancer Patients: Psychometric Properties of the Cancer Inventory of Problem Situations. Health Psychol 1990, 9(1):83–102.

Schultz-Larsen K, Avlund K, Kreiner S: Functional ability of community dwelling elderly. Criterion-related validity of a new measure of functional ability. J Clin Epidemiol 1992, 45(11):1315–1326.

Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B: Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. J Clin Epidemiol 1989, 42(8):703–709.

Sintonen H: The 15-D Measure of Health Reated Quality of Life: Reliability, Validity and Sensitivity of its Health State Descriptive System. 1994.

Sintonen H: The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med 2001, 33(5):328–336.

So CT, Man DWK: Development and validation of an activities of daily living inventory for the rehabilitation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. OTJR: Occupation, Participation & Health 2008, 28(4):149–159.

Stel VS, Smit JH, Pluijm SM, Visser M, Deeg DJ, Lips P: Comparison of the LASA Physical Activity Questionnaire with a 7-day diary and pedometer. J Clin Epidemiol 2004, 57(3):252–258.

Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, Haskell WL, Gillis D, Ritter PL: CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: outcomes for interventions. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2001, 33(7):1126–1141.

Tinetti ME, Richman D, Powell L: Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J Gerontol 1990, 45(6):P239-P243.

Tu SP, McDonell MB, Spertus JA, Steele BG, Fihn SD: A new self-administered questionnaire to monitor health-related quality of life in patients with COPD. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP) Investigators. Chest 1997, 112(3):614–622.

Tugwell P, Bombardier C, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Grace E, Hanna B: The MACTAR Patient Preference Disability Questionnaire-an individualized functional priority approach for assessing improvement in physical disability in clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1987, 14(3):446–451.

van der Molen T, Willemse BW, Schokker S, ten Hacken NH, Postma DS, Juniper EF: Development, validity and responsiveness of the Clinical COPD Questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003, 1: 13.

Verbunt JA: Reliability and validity of the PAD questionnaire: a measure to assess pain-related decline in physical activity. J Rehabil Med 2008, 40(1):9–14.

Voorrips LE, Ravelli AC, Dongelmans PC, Deurenberg P, Van Staveren WA: A physical activity questionnaire for the elderly. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 1991, 23(8):974–979.

Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA: The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol 1993, 46(2):153–162.

Weaver TE, Narsavage GL, Guilfoyle MJ: The development and psychometric evaluation of the Pulmonary Functional Status Scale: an instrument to assess functional status in pulmonary disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 1998, 18(2):105–111.

Wigal JK, Creer TL, Kotses H: The COPD Self-Efficacy Scale. Chest 1991, 99(5):1193–1196.

Windisch W, Freidel K, Schucher B, Baumann H, Wiebel M, Matthys H, Petermann F: The Severe Respiratory Insufficiency (SRI) Questionnaire A specific measure of health-related quality of life in patients receiving home mechanical ventilation. J Clin Epidemiol 2003, 56(8):752–759.

Yohannes AM, Roomi J, Winn S, Connolly MJ: The Manchester Respiratory Activities of Daily Living questionnaire: development, reliability, validity, and responsiveness to pulmonary rehabilitation. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000, 48(11):1496–1500.

Yoza Y, Ariyoshi K, Honda S, Taniguchi H, Senjyu H: Development of an activity of daily living scale for patients with COPD: the Activity of Daily Living Dyspnoea scale. Respirology 2009, 14(3):429–435.

Topolski TD, LoGerfo J, Patrick DL, Williams B, Walwick J, Patrick MB: The Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (RAPA) among older adults. Prev Chronic Dis 2006, 3(4):A118.

Zaragoza J, Lugli-Rivero Z: Development and Validation of a Quality of Life Questionnaire for Patients with Chronic Respiratory Disease (CV-PERC): Preliminary Results. Construccion y validacion del instrumento Calidad de Vida en Pacientes con Enfermedades Respiratorias Cronicas (CV-PERC) Resultados preliminares 2009, 45(2):81.

Zhou YQ, Chen SY, Jiang LD, Guo CY, Shen ZY, Huang PX, Wang JY: Development and evaluation of the quality of life instrument in chronic liver disease patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009, 24(3):408–415.

Zisberg A: Influence of routine on functional status in elderly: development and validation of an instrument to measure routine. University of Washington; 2005.

Mancuso CA, Sayles W, Robbins L, Phillips EG, Ravenell K, Duffy C, Wenderoth S, Charlson ME: Barriers and facilitators to healthy physical activity in asthma patients. J Asthma 2006, 43(2):137–143.

Gimeno-Santos E, Frei A, Dobbels F, Rudell K, Puhan MA, Garcia-Aymerich J: Validity of instruments to measure physical activity may be questionable due to a lack of conceptual frameworks: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011, 9: 86.

Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, Schnohr P, Anto JM: Regular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort study. Thorax 2006, 61(9):772–778.

Ainsworth BE, Jacobs DR Jr, Leon AS: Validity and reliability of self-reported physical activity status: the Lipid Research Clinics questionnaire. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 1993, 25(1):92–98.

Ainsworth BE, Leon AS, Richardson MT, Jacobs DR, Paffenbarger RS Jr: Accuracy of the College Alumnus Physical Activity Questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol 1993, 46(12):1403–1411.

Almeida MH, de Pinho Spinola AW, Iwamizu PS, Okura RI, Barroso LP, Lima AC: Reliability of the instrument for classifying elderly people's capacity for self-care. Rev Saude Publica 2008, 42(2):317–323.

Anders J, Dapp U, Laub S, von RentelnKruse W: Impact of fall risk and fear of falling on mobility of independently living senior citizens transitioning to frailty: Screening results concerning fall prevention in the community. Z Gerontol Geriatr 2007, 40(4):255–267.

Araki A, Izumo Y, Inoue J, et al.: Development of Elderly Diabetes Impact Scales (EDIS) in elderly patients with diabetes mellitus. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi - Japanese Journal of Geriatrics 1995, 32(12):786–796.

Arbuckle TY, Gold D, Andres D: Cognitive functioning of older people in relation to social and personality variables. Psychol Aging 1986, 1(1):55–62.

Avlund K, Kreiner S, Schultz-Larsen K: Construct validation and the Rasch model: functional ability of healthy elderly people. Scand J Soc Med 1993, 21(4):233–246.

Badia X, Webb SM, Prieto L, Lara N: Acromegaly Quality of Life Questionnaire (AcroQoL). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004, 2: 13.

Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE: A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr 1982, 36(5):936–942.

Bandura A: Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman & Co 1997.

Barber JH, Wallis JB, McKeating E: A postal screening questionnaire in preventive geriatric care. J R Coll Gen Pract 1980, 30(210):49–51.

Barberger-Gateau P, Commenges D, Gagnon M, Letenneur L, Sauvel C, Dartigues J: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living as a screening tool for cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly community dwellers. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992, 40(11):1129–1134.

Barberger-Gateau P, Rainville C, Letenneur L, Dartigues J: A hierarchical model of domains of disablement in the elderly: a longitudinal approach. Disabil Rehabil 2000, 22(7):308–317.

Basler HD, Luckmann J, Wolf U, Quint S: Fear-avoidance beliefs, physical activity, and disability in elderly individuals with chronic low back pain and healthy controls. Clin J Pain 2008, 24(7):604–610.

Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Steiner JF: Subjective assessments of comorbidity correlate with quality of life health outcomes: initial validation of a comorbidity assessment instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005, 3: 51.

Bennell KL, Hinman RS, Crossley KM, et al.: Is the Human Activity Profile a useful measure in people with knee osteoarthritis? J Rehabil Res Dev 2004, 41(4):621–629.

Berg K, W DS, LW J: Measuring balance in the elderly: preliminary development of an instrument. Physiother Can 1989, 41(6):301–311.

Bergland A, Jarnlo G, Laake K: Validity of an index of self-reported walking for balance and falls in elderly women. Advances in Physiotherapy 2002, 4(2):65–73.

Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA: Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999, 54(7):581–586.

Binder EF, Miller JP, Ball LJ: Development of a test of physical performance for the nursing home setting. Gerontologist 2001, 41(5):671–679.

Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Leblanc C, Lortie G, Savard R, Theriault G: A method to assess energy expenditure in children and adults. Am J Clin Nutr 1983, 37(3):461–467.

Boult C, Krinke UB, Urdangarin CF, Skarin V: The validity of nutritional status as a marker for future disability and depressive symptoms among high-risk older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999, 47(8):995–999.

Bowns I, Challis D, Tong MS: Case finding in elderly people: validation of a postal questionnaire. Br J Gen Pract 1991, 41(344):100–104.

Braido F, Baiardini I, Tarantini F, et al.: Chronic cough and QoL in allergic and respiratory diseases measured by a new specific validated tool-CCIQ. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2006, 16(2):110–116.

Budzynski HK, Budzynski T: Perceived Physical Functioning Scale for community dwelling elderly... 34th Annual Communicating Nursing Research Conference/15th Annual WIN Assembly, "Health Care Challenges Beyond 2001: Mapping the Journey for Research and Practice," held April 19–21, 2001 in Seattle, Washington. Commun Nurs Res 2001, 34: 325–325.

Burckhardt CS, Woods SL, Schultz AA, Ziebarth DM: Quality of life of adults with chronic illness: a psychometric study. Res Nurs Health 1989, 12(6):347–354.

Carter R, Holiday DB, Grothues C, Nwasuruba C, Stocks J, Tiep B: Criterion validity of the Duke Activity Status Index for assessing functional capacity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2002, 22(4):298–308.

Cartmel B, Moon TE: Comparison of two physical activity questionnaires, with a diary, for assessing physical activity in an elderly population. J Clin Epidemiol 1992, 45(8):877–833.

Chasan-Taber S, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, et al.: Reproducibility and Validity of a Self-Administered Physical Activity Questionnaire for Male Health Professionals. Epidemiology 1996, 7(1):81–86.

Chen H, Eisner MD, Katz PP, Yelin EH, Blanc PD: Measuring disease-specific quality of life in obstructive airway disease: Validation of a modified version of the airways questionnaire 20. Chest 2006, 129(6):1644.

Chen Q, Kane RL: Effects of using consumer and expert ratings of an activities of daily living scale on predicting functional outcomes of postacute care. J Clin Epidemiol 2001, 54(4):334–342.

Chester GA: Normative data for the brief symptom inventory for mature and independent living adults. 2001.

Chiou C: Development and psychometric assessment of the Physical Symptom Distress Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage 1998, 16(2):87–95.

Choi YH, Kim MS, Byon YS, Won JS: [Health status of elderly persons in Korea]. Kanho Hakhoe Chi [Journal of Nurses Academic Society] 1990, 20(3):307–323.

Clarke JE, Eccleston C: Assessing the quality of walking in adults with chronic pain: the development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of the Bath Assessment of Walking Inventory. European Journal of Pain: Ejp 2009, 13(3):305–311.

Coleman EA, Wagner EH, Grothaus LC, Hecht J, Savarino J, Buchner DM: Predicting hospitalization and functional decline in older health plan enrollees: are administrative data as accurate as self-report?[see comment]. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998, 46(4):419–425.

Colombel JF, Yazdanpanah Y, Laurent F, Houcke P, Delas N, Marquis P: Quality of life in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. Validation of a questionnaire and first French data. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1996, 20(12):1071–1077.

Covinsky KE, Hilton J, Lindquist K, Dudley RA: Development and validation of an index to predict activity of daily living dependence in community-dwelling elders. Medical care 2006, 44(2):149–157.

Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Counsell SR, Pine ZM, Walter LC, Chren M: Functional status before hospitalization in acutely ill older adults: Validity and clinical importance of retrospective reports. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000, 48(2):164–169.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, et al.: International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 2003, 35(8):1381–1395.

Crawford B, Monz B, Hohlfeld J, et al.: Development and validation of a cough and sputum assessment questionnaire. Respir Med 2008, 102(11):1545–1555.

Creel GL, Light KE, Thigpen MT: Concurrent and construct validity of scores on the Timed Movement Battery. Phys Ther 2001, 81(2):789–798.

Crockett DJ, Tuokko H, Koch W, Parks R: The assessment of everyday functioning using the Present Functioning Questionnaire and the Functional Rating Scale in elderly samples. Clin Gerontol 1989, 8(3):3–25.

Crouch MJ: Assessing components of loss-related dysfunction in the elderly. 2003.

Cullum CM, Saine K, Chan LD, Martin-Cook K, Gray KF, Weiner MF: Performance- Based instrument to assess functional capacity in dementia: The Texas Functional Living Scale. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 2001, 14(2):103–108.

Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Sonn U, Svensson E: Development of an ADL instrument targeting elderly persons with age-related macular degeneration. Disabil Rehabil 2001, 23(2):69–79.

Daltroy LH, Phillips CB, Eaton HM, et al.: Objectively measuring physical ability in elderly persons: the Physical Capacity Evaluation. Am J Public Health 1995, 85(4):558–560.

De Leo D, Diekstra RF, Lonnqvist J, et al.: LEIPAD, an internationally applicable instrument to assess quality of life in the elderly. Behav Med 1998, 24(1):17–27.

de Veer AJ, de Bakker DH: Measuring unmet needs to assess the quality of home health care. Int J Qual Health Care 1994, 6(3):267–274.

Deniston OL, Jette A: A functional status assessment instrument: validation in an elderly population. Health Serv Res 1980, 15(1):21–34.

Devins GM: Using the illness intrusiveness ratings scale to understand health-related quality of life in chronic disease. Journal of psychosomatic research 2009. Journal Article

Devins GM, Binik YM, Hutchinson TA, Hollomby DJ, Barre PE, Guttmann RD: The emotional impact of end-stage renal disease: importance of patients' perception of intrusiveness and control. Int J Psychiatry Med 1983, 13(4):327–343.

Devlen JMSMP: Measuring Quality of Life: A Disease-Specific Approach.

Deyo RA, Inui TS, Leininger JD, Overman SS: Measuring functional outcomes in chronic disease: a comparison of traditional scales and a self-administered health status questionnaire in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Medical care 1983, 21(2):180–192.

Dickerson AE, Fisher AG: Culture-relevant functional performance assessment of the Hispanic elderly. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research 1995, 15(1):50–68.

Dinger MK, Oman RF, Taylor EL, Vesely SK, Able J: Stability and convergent validity of the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE). J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2004, 44(2):186–192.

Dixon D, Pollard B, Johnston M: What does the chronic pain grade questionnaire measure? Pain 2007, 130(3):249–253.

Doble SE, Fisher AG: The dimensionality and validity of the Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale. J Outcome Meas 1998, 2(1):4–24.

DuBose KD, Edwards S, Ainsworth BE, Reis JP, Slattery ML: Validation of a historical physical activity questionnaire in middle-aged women. J Phys Act Health 2007, 4(3):343–355.

Duiverman ML, Wempe JB, Bladder G, Kerstjens HA, Wijkstra PJ: Health-related quality of life in COPD patients with chronic respiratory failure. The European respiratory journal: official journal of the European Society for Clinical Respiratory Physiology 2008, 32(2):379.

Eakman AM: A reliability and validity study of the Meaningful Activity Participation Assessment. 2008.

Eaton T, Young P, Fergusson W, Garrett JE, Kolbe J: The Dartmouth COOP Charts: A simple, reliable, valid and responsive quality of life tool for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation 2005, 14(3):577–585.

Edwards R, Telfair J, Cecil H, Lenoci J: Reliability and validity of a self-efficacy instrument specific to sickle cell disease. Behav Res Ther 2000, 38(9):951–963.

Eisner MD, Trupin L, Katz PP, et al.: Development and validation of a survey-based COPD severity score. Chest 2005, 127(6):1890.

Fabris F: MMPMFGVPSC. Dependance medical index (DMI) in elderly persons: a tool for identification of dependence for medical reasons. Bold 1996, 6: 9–12.

Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O'Brien JP: The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy 1980, 66(8):271–273.

Feitel B: A checklist for measuring nonfunctional behavior of regressed chronic psychiatric patients. J Clin Psychol 1981, 37(1):158–160.

Fillenbaum GG, Chandra V, Ganguli M, et al.: Development of an activities of daily living scale to screen for dementia in an illiterate rural older population in India. Age Ageing 1999, 28(2):161–168.

Fillenbaum GG, Pfeiffer E: The Mini-Mult: A cautionary note. J Consult Clin Psychol 1976, 44(5):698–703.

Fine MA, Tangeman PJ: Adaptive Behavior Scale predictive validity with elderly male veterans. Clin Gerontol 1993, 14(2):27–31.

Fisher AG: The assessment of IADL motor skills: an application of many-faceted Rasch analysis. American journal of occupational therapy.: official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association 1993, 47(4):319–329.

Floyd FJ, Haynes SN, Doll ER, et al.: Assessing retirement satisfaction and perceptions of retirement experiences. Psychol Aging 1992, 7(4):609–621.

Frederiks CMA, te Wierik MJM, Visser AP, Sturmans F: A scale for the functional status of the elderly living at home. J Adv Nurs 1991, 16(3):287–292.

Gabel CP, Michener LA, Burkett B, Neller A: The Upper Limb Functional Index: development and determination of reliability, validity, and responsiveness. Journal of hand therapy: official journal of the American Society of Hand Therapists 2006, 19(3):328–348. quiz 349

Gerety MB, Mulrow CD, Tuley MR, et al.: Development and validation of a physical performance instrument for the functionally impaired elderly: the Physical Disability Index (PDI). J Gerontol 1993, 48(2):M33-M38.

Gosman-Hedstrom G, Svensson E: Parallel reliability of the functional independence measure and the Barthel ADL index. Disabil Rehabil 2000, 22(16):702–715.

Granger Carl VMD, Benjamin D, Wright P: Looking ahead to the use of functional assessment in ambulatory physiatric and primary care. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America: New Developments in Functional Assessment 1993, 4(3):595–605.

Granger CV, Ottenbacher KJ, Baker JG, Sehgal A: Reliability of a brief outpatient functional outcome assessment measure. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation/Association of Academic Physiatrists 1995, 74(6):469–475.

Greenland P, Ries AL, Williams MA: Literature update: selected abstracts from recent publications in cardiac and pulmonary disease prevention, rehabilitation, and exercise physiology. [Commentary on] Development and validation of a standardized measure of activity of daily living in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the London Chest Activity of Daily Living Scale. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2001, 21(3):178–179.

Gulick EE: Reliability and validity of the work assessment scale for persons with multiple sclerosis. Nurs Res 1991, 40(2):107–112.

Gulick EE, Yam M, Touw MM: Work performance by persons with multiple sclerosis: conditions that impede or enable the performance of work. Int J Nurs Stud 1989, 26(4):301–311.

Haapaniemi TH, Sotaniemi KA, Sintonen H, Taimela E: The generic 15D instrument is valid and feasible for measuring health related quality of life in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004, 75(7):976–983.

Hagg O, Fritzell P, Romberg K, Nordwall A: The General Function Score: a useful tool for measurement of physical disability. Validity and reliability. European spine journal: official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society 2001, 10(3):203–210.

Han CW, Yajima Y, Lee EJ, et al.: Development and construct validation of the Korean competence scale (KCS). Tohoku J Exp Med 2004, 203(4):331–337.

Harada K, Ota A, Shibata A, Oka K, Nakamura Y, Muraoka I: Development of the exercise-specified subjective health status scale for the frail elderly... 7th World Congress on Aging and Physical Activity. J Aging Phys Act 2008, 16: 185–185.

Harwood RH, Rogers A, Dickinson E, Ebrahim S: Measuring handicap: the London Handicap Scale, a new outcome measure for chronic disease. Qual Health Care 1994, 3(1):11–16.

Hebert R, Carrier R, Bilodeau A: The Functional Autonomy Measurement System (SMAF): description and validation of an instrument for the measurement of handicaps. Age Ageing 1988, 17(5):293–302.

Hidalgo JL, Gras CB, Lapeira JM, et al.: The Hearing-Dependent Daily Activities Scale to evaluate impact of hearing loss in older people. Ann Fam Med 2008, 6(5):441–447.

Hiratsuka T, Kida K: Quality of life measurements using a linear analog scale for elderly patients with chronic lung disease. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 1993, 32(11):832–836.

Hodgev V, Kostianev S, Marinov B: University of Cincinnati Dyspnea Questionnaire for Evaluation of Dyspnoea during physical and speech activities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a validation analysis. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2003, 23(5):269–274.

Holm I, Friis A, Storheim K, Brox JI: Measuring self-reported functional status and pain in patients with chronic low back pain by postal questionnaires: a reliability study. Spine 2003, 28(8):828–833.

Huijbregts MP, Teare GF, McCullough C, et al.: Standardization of the continuing care activity measure: a multicenter study to assess reliability, validity, and ability to measure change. Phys Ther 2009, 89(6):546–555.

Iida N, Kohashi N, Koyama W: The reliability and validity of a new self-completed questionnaire (QUIK). Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi - Japanese Journal of Geriatrics 1995, 32(2):96–100.

Incalzi RA, Corsonello A, Pedone C, et al.: Construct validity of activities of daily living scale: a clue to distinguish the disabling effects of COPD and congestive heart failure. Chest 2005, 127(3):830–838.

Itzkovich M, Catz A, Tamir A, et al.: Spinal pain independence measure-a new scale for assessment of primary ADL dysfunction related to LBP. Disabil Rehabil 2001, 23(5):186–191.

Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Strom SE: The Chronic Pain Coping Inventory: development and preliminary validation. Pain 1995, 60(2):203–216.

Jette AM, Davies AR, Cleary PD, et al.: The Functional Status Questionnaire: reliability and validity when used in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 1986, 1(3):143–149.

Kai I, Ohi G, Kobayashi Y, Ishizaki T, Hisata M, Kiuchi M: Quality of life: a possible health index for the elderly. Asia Pac J Public Health 1991, 5(3):221–227.

Kames LD, Naliboff BD, Heinrich RL, Schag CC: The chronic illness problem inventory: problem-oriented psychosocial assessment of patients with chronic illness. Int J Psychiatry Med 1984, 14(1):65–75.

Katsura H, Yamada K, Kida K: Usefulness of a linear analog scale questionnaire to measure health-related quality of life in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003, 51(8):1131–1135.

Katz JN, Wright EA, Baron JA, Losina E: Development and validation of an index of musculoskeletal functional limitations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009, 10: 62.

Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW: Studies of Illness in the Aged. the Index of Adl: a Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA 1963, 185: 914–919.

Kincannon JC: Prediction of the standard MMPI scale scores from 71 items: the mini-mult. J Consult Clin Psychol 1968, 32(3):319–325.

Lachman ME, Howland J, Tennstedt S, Jette A, Assmann S, Peterson EW: Fear of falling and activity restriction: the survey of activities and fear of falling in the elderly (SAFE). Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences 1998, 53(1):P43-P50.

Larson JL, Kapella MC, Wirtz S, Covey MK, Berry J: Reliability and validity of the Functional Performance Inventory in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Nurs Meas 1998, 6(1):55–73.

Lawton MP, Brody EM: Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969, 9(3):179–186.

Leeuw M, Goossens ME, van Breukelen GJ, Boersma K, Vlaeyen JW: Measuring perceived harmfulness of physical activities in patients with chronic low back pain: the Photograph Series of Daily Activities-short electronic version. J Pain 2007, 8(11):840–849.

Leidy NK: Using functional status to assess treatment outcomes. Chest 1994, 106(6):1645–1646.

Leidy NK: Functional status and the forward progress of merry-go-rounds: toward a coherent analytical framework. Nurs Res 1994, 43(4):196–202.

Leidy NK, Knebel AR: Clinical validation of the functional performance inventory in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Care 1999, 44(8):932.

Leidy NK, Schmier JK, Jones MK, Lloyd J, Rocchiccioli K: Evaluating symptoms in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: validation of the Breathlessness, Cough and Sputum Scale. Respir Med 2003, 97: 59–70.

Lennon S, Johnson L: The modified rivermead mobility index: validity and reliability. Disabil Rehabil 2000, 22(18):833–839.

Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Quear T, et al.: The Pittsburgh Rehabilitation Participation Scale: reliability and validity of a clinician-rated measure of participation in acute rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004, 85(3):380–384.

Letts L, Scott S, Burtney J, Marshall L, McKean M: The reliability and validity of the safety assessment of function and the environment for rehabilitation (SAFER tool). British Journal of Occupational Therapy 1998, 61(3):127–132.

Leung AS, Chan KK, Sykes K, Chan KS: Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of a 2-min walk test to assess exercise capacity of COPD patients. Chest 2006, 130(1):119–125.

Levine S, Gillen M, Weiser P, Feiss G, Goldman M, Henson D: Inspiratory pressure generation: comparison of subjects with COPD and age-matched normals. J Appl Physiol 1988, 65(2):888–899.

Lincoln NB, Gladman JR: The Extended Activities of Daily Living scale: a further validation. Disabil Rehabil 1992, 14(1):41–43.

Linn MW, Linn BS: Self-evaluation of life function (self) scale: a short, comprehensive self-report of health for elderly adults. J Gerontol 1984, 39(5):603–612.

Linzer M, Gold DT, Pontinen M, Divine GW, Felder A, Brooks WB: Recurrent syncope as a chronic disease: preliminary validation of a disease-specific measure of functional impairment. J Gen Intern Med 1994, 9(4):181–186.

Littman AJ, White E, Kristal AR, Patterson RE, Satia-Abouta J, Potter JD: Assessment of a one-page questionnaire on long-term recreational physical activity. Epidemiology 2004, 15(1):105–113.

Livingston G, Watkin V, Manela M, Rosser R, Katona C: Quality of life in older people. Aging Ment Health 1998, 2(1):20–23.

Ljungquist T, Nygren A, Jensen I, Harms-Ringdahl K: Physical performance tests for people with spinal pain-sensitivity to change. Disabil Rehabil 2003, 25(15):856–866.

Lundin-Olsson L, Nyberg L, Gustafson Y: Attention, frailty, and falls: the effect of a manual task on basic mobility. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998, 46(6):758–761.

Macfarlane DJ, Chou KL, Cheng YH, Chi I: Validity and normative data for thirty-second chair stand test in elderly community-dwelling Hong Kong Chinese. Am J Hum Biol 2006, 18(3):418–421.

MacKenzie CR, Charlson ME, DiGioia D, Kelley K: A patient-specific measure of change in maximal function. Arch Intern Med 1986, 146(7):1325–1329.

MacKnight C, Rockwood K: A Hierarchical Assessment of Balance and Mobility. Age Ageing 1995, 24(2):126–130.

Maeda A, Yuasa T, Nakamura K, Higuchi S, Motohashi Y: Physical performance tests after stroke: reliability and validity. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2000, 79(6):519–525.

Magnussen L, Strand LI, Lygren H: Reliability and validity of the back performance scale: observing activity limitation in patients with back pain. Spine 2004, 29(8):903–907.

Mahoney RI, Barthel DW, Shah Surya: Professor Occupational Therapy and Neurology, Visiting Professor Neurorehabilitation, University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center, 930 Madison, Suite 601, Memphis, TN 38163. 1965, 1: 1.

Mahurin RK, DeBettignies BH, Pirozzolo FJ: Structured assessment of independent living skills: preliminary report of a performance measure of functional abilities in dementia. J Gerontol 1991, 46(2):P58-P66.

Majani G, Callegari S, Pierobon A, Giardini A, Vidotto G: Satisfaction profile (SAT-P): A new evaluation instrument in a clinical environment. Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale 1997, 3(1):27–41.