Abstract

Background

KRAS mutations in codons 12 and 13 are established predictive biomarkers for anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Previous studies suggest that KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations may also predict resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. However, clinicopathological, molecular, and prognostic features of colorectal carcinoma with KRAS codon 61 or 146 mutation remain unclear.

Methods

We utilized a molecular pathological epidemiology database of 1267 colon and rectal cancers in the Nurse’s Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. We examined KRAS mutations in codons 12, 13, 61 and 146 (assessed by pyrosequencing), in relation to clinicopathological features, and tumor molecular markers, including BRAF and PIK3CA mutations, CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), LINE-1 methylation, and microsatellite instability (MSI). Survival analyses were performed in 1067 BRAF-wild-type cancers to avoid confounding by BRAF mutation. Cox proportional hazards models were used to compute mortality hazard ratio, adjusting for potential confounders, including disease stage, PIK3CA mutation, CIMP, LINE-1 hypomethylation, and MSI.

Results

KRAS codon 61 mutations were detected in 19 cases (1.5%), and codon 146 mutations in 40 cases (3.2%). Overall KRAS mutation prevalence in colorectal cancers was 40% (=505/1267). Of interest, compared to KRAS-wild-type, overall, KRAS-mutated cancers more frequently exhibited cecal location (24% vs. 12% in KRAS-wild-type; P < 0.0001), CIMP-low (49% vs. 32% in KRAS-wild-type; P < 0.0001), and PIK3CA mutations (24% vs. 11% in KRAS-wild-type; P < 0.0001). These trends were evident irrespective of mutated codon, though statistical power was limited for codon 61 mutants. Neither KRAS codon 61 nor codon 146 mutation was significantly associated with clinical outcome or prognosis in univariate or multivariate analysis [colorectal cancer-specific mortality hazard ratio (HR) = 0.81, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.29-2.26 for codon 61 mutation; colorectal cancer-specific mortality HR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.42-1.78 for codon 146 mutation].

Conclusions

Tumors with KRAS mutations in codons 61 and 146 account for an appreciable proportion (approximately 5%) of colorectal cancers, and their clinicopathological and molecular features appear generally similar to KRAS codon 12 or 13 mutated cancers. To further assess clinical utility of KRAS codon 61 and 146 testing, large-scale trials are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Use of Standardized Official Symbols: We use HUGO (Human Genome Organisation)-approved official symbols for genes and gene products, including BRAF; EGFR; KRAS; PIK3CA; all of which are described at http://www.genenames.org.

Colorectal cancer represents a heterogeneous group of diseases, and its molecular classification is increasingly important. Colorectal cancers can be classified using mutations in oncogenes such as KRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA[1]. In addition, microsatellite instability (MSI) and epigenomic instability, such as the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) and LINE-1 hypomethylation, have been associated with the oncogene mutations and clinical outcomes[1–4].

Approximately 30-40% of colorectal cancers harbor KRAS mutations, typically in codon 12 or 13[5–9]. Features of colorectal cancers with KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations include associations with cecal location[5, 8], low-level CIMP (CIMP-low)[10–14], and PIK3CA mutation[15–18]. KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations are widely accepted as a predictive biomarker of lack of response to anti-EGFR therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer[19–23], though a few exploratory studies suggest that codon 13 mutants may benefit from EGFR-targeted therapy[24, 25].

KRAS codons 61 and 146 are additional hotspots for mutation in colorectal cancer, and data from a small number of studies suggest that KRAS mutation at these sites may predict resistance to anti-EGFR therapy[26–28]. Recently, Douillard et al., utilizing existing clinical trial data, reported that KRAS mutations in codons 61, 146, and 117, and mutations in NRAS, might identify patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who fail to derive benefit from panitumumab plus FOLFOX4[29]. Despite growing clinical relevance, the clinicopathological and molecular features of colorectal cancers with KRAS codon 61 or 146 mutation remain largely unknown. It is of interest to examine the characteristics of colorectal cancers with KRAS mutations in codons 61 and 146, compared to those in codons 12 and 13, and KRAS-wild-type cases. In the near future, routine clinical testing of these additional KRAS codons may be warranted.

We therefore investigated the clinicopathological, molecular, and prognostic characteristics of tumors harboring KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations, utilizing a molecular pathological epidemiology[30, 31] database of 1267 colorectal cancers from two U.S. nationwide prospective cohort studies. We also performed a comprehensive review on KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations in colorectal cancer, and our curated literature data can be readily useful for public databases such as the COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) database.

Results

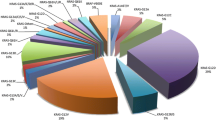

KRAS codon 12, 13, 61 and 146 mutations, in relation to clinicopathological and molecular features

We detected KRAS mutations in 505 (40%) cases in 1267 colorectal cancers (Table 1). Codon 12 mutations were present in 344 cases (27%), codon 13 mutations in 115 cases (9.1%), codon 61 mutations in 19 cases (1.5%), and codon 146 mutations in 40 cases (3.2%). There were 493 cases with KRAS mutations identified in only one of codons 12, 13, 61 and 146, and 12 cases with KRAS mutations identified in two or more of the four codons (Table 1).

The baseline characteristics of study subjects are summarized in Table 2, according to tumor KRAS mutation status. Compared to KRAS-wild-type tumors, overall KRAS-mutated cancers were less likely to exhibit poor differentiation (5.8%, P < 0.0001), MSI-high (6.2%, P < 0.0001), and BRAF mutation (1.4%, P < 0.0001), and more likely to demonstrate cecal location (24%, P < 0.0001), CIMP-low (49%, P < 0.0001), and PIK3CA mutation (24%, P < 0.0001). Of note, these trends were generally evident across case groups with specific mutated codons (Table 2). KRAS mutation status was not significantly associated with sex, age, body mass index (BMI), year of diagnosis, family history of colorectal cancer, disease stage, peritumoral lymphocytic reaction, or tumor LINE-1 methylation level. There was no significant difference in any of the features between the cases with KRAS mutations identified in only one codon (N = 493) and those with KRAS mutations identified in two or more codons (N = 12), though statistical power was limited, given only 12 cases with KRAS mutations identified in multiple codons (Additional file1: Table S1).

KRAS mutation status and patient survival in BRAF-wild-type cases

To examine the prognostic role of KRAS mutation independent of BRAF mutation, within 1067 BRAF-wild-type cases (excluding BRAF mutants), we compared KRAS-mutated cancers to cases with wild-type KRAS in all four codons 12, 13, 61 and 146 (Additional file2: Table S2). We evaluated clinicopathological, molecular and survival data of 51 cases with KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations (Additional file3: Table S3). There were 514 deaths, including 307 colorectal cancer-specific deaths, during a median follow-up of 11.7 years (interquartile range, 8.3-16.1 years) for censored cases.

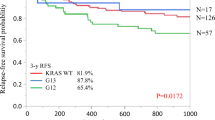

The 5-year colorectal cancer-specific survival probabilities were 80.6% for cases with KRAS-wild-type/BRAF-wild-type tumors, 67.9% for cases with codon 12 mutations, 75.8% for cases with codon 13 mutations, 79.4% for cases with codon 61 mutations, and 76.7% for cases with codon 146 mutations. Specific KRAS mutations were significantly associated with patient survival in Kaplan-Meier analysis (log-rank P = 0.0014, Figure 1). In multivariate analysis, compared to KRAS-wild-type/BRAF-wild-type tumors, we observed a significant prognostic association for KRAS codon 12 mutation [multivariate hazard ratio (HR) = 1.45; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.12-1.87; P = 0.0048; Table 3). However, neither mutation of KRAS codon 61 nor codon 146 was associated with patient outcome (Table 3). For cases with the 10 most common KRAS mutations across all four codons examined, those with the c.34G>T (p.G12C) mutation, and those with the c.35G>T (p.G12V) mutation experienced significantly higher colorectal cancer-specific mortality in Cox regression analysis [multivariate HR = 2.33; 95% CI, 1.36-3.99; P = 0.0021 for c.34G>T (p.G12C); multivariate HR = 2.13; 95% CI, 1.47-3.09; P < 0.0001 for c.35G>T (p.G12V); Table 3], even after adjusting a statistical significance level for multiple testing (P < 0.005). None of the three most common KRAS mutations in codons 61 and 146 [c.183A>C (p.Q61H), c.436G>A (p.A146T) and c.437C>T (p.A146V)] was associated with patient prognosis (Table 3), although statistical power was limited. Subgroup analyses of stage I-II cases (N = 544, Additional file4: Table S4), and stage III-IV cases (N = 414, Additional file5: Table S5) yielded similar results, although statistical power was limited.

Kaplan-Meier curves for colorectal cancer patients with BRAF- wild-type tumors, according to tumor KRAS mutation status. (A) Colorectal cancer-specific survival. (B) Overall survival. Table indicates the number of patients who were alive and at risk of death at each time point after diagnosis of colorectal cancer.

Discussion

Although a number of studies have examined codon 61 or 146 hotspot mutations in colorectal cancer (Additional file6: Table S6)[26–29, 32–74], clinicopathological, molecular, and prognostic characteristics of those mutations have not been well investigated. Our data, from 1267 tumors, suggest that approximately 5% of all colorectal cancers harbor KRAS mutations in codon 61 or 146, and those colorectal cancers generally show similar characteristics to tumors with KRAS mutations in codon 12 or 13 (including associations with cecal location, CIMP-low and PIK3CA mutations).

A variety of methods have been used for KRAS codon 61 and 146 analyses (Additional file6: Table S6)[26–29, 32–74], which might have contributed to a wide variation in the prevalence of those mutations. Generally, nonsequencing methods make it cumbersome to confirm multiple independent mutations, and make it difficult to detect multiple variations at one allele without employing an expanded panel of probes or primers. Of the sequencing-based methodologies, pyrosequencing has been shown to be more sensitive than Sanger sequencing in paraffin-embedded archival tissue, with the capacity to reliably detect mutant alleles at low abundance (5-10% mutant), which is common in solid tumors[75].

The association between cecal cancers and KRAS mutations is intriguing. Emerging data suggest that gut luminal contents and microbiota, which change along bowel subsites, play important roles in colorectal carcinogenesis[8, 76]. Our recent study on colorectal cancers in detailed subsites (from cecum to rectum) has shown that tumor molecular features (including BRAF mutation, MSI and CIMP-high) change along the bowel subsites, and that cecal cancers are associated with KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations[5, 8]. In our current study, cecal cancers appeared to be significantly associated with overall KRAS mutation status, and this trend was evident across all four mutated codons. Further studies are needed to elucidate why KRAS mutations, irrespective of mutated codon, are particularly common in cecal cancers.

Examining associations of tumor molecular features can provide insights into carcinogenesis processes, and is important in cancer research[77–83]. Previous studies have demonstrated that KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations are associated with aberrant DNA methylation patterns, namely CIMP-low[10, 11]. Our current study suggests that KRAS mutation, irrespective of mutated codon (statistical power was limited for codon 61 mutants), is associated with CIMP-low. It remains to be investigated why KRAS mutations are associated with CIMP-low in colorectal cancer. KRAS have been positively associated with PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancer[15–18]. Our data suggest that KRAS mutations, irrespective of mutated codon, are associated with PIK3CA mutations. It has been reported that activated RAS signaling potentiates PI3K (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphonate 3-kinase)/AKT signaling, which is augmented by the presence of PIK3CA mutations[84]. Considering a possible role for PIK3CA mutation as a predictive biomarker of response to adjuvant aspirin therapy in colorectal cancer[16], our finding may be of interest. KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations have been inversely associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer[17, 26, 33, 41]. Our current data suggest that KRAS mutations, irrespective of mutated codon, are inversely associated with MSI-high and BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer. LINE-1 methylation level is a surrogate marker for global DNA methylation, and has been reported to be associated with MSI-high and CIMP-high in colorectal cancer[85]. This study showed that LINE-1 methylation level in average did not significantly differ according to KRAS mutation status.

Experimental studies are consistent with our observations that both KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations can contribute to carcinogenesis in a similar manner to oncogenic mutations in codons 12 and 13. As KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations, codon 61 mutation results in oncogenic RAS with impaired GTPase activity, resulting in constitutive activation[86, 87]. KRAS codon 146 mutation-transfected HEK-293FT cells showed a larger amount of RAS-GTP compared to KRAS-wild-type-transfected cells[28]. These experimental data provide an insights into plausible functional roles of codon 61 and 146 mutations in carcinogenesis.

In our current survival analysis, there was no significant association between KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations, and patient outcome. The prognostic value of KRAS mutation in colorectal cancer remains controversial[7, 88–92]. Of note, in our current study, when we separately examined specific KRAS mutations, codon 12 mutations [especially c.34G>T (p.G12C) and c.35G>T (p.G12V)] were significantly associated with inferior survival, which is consistent with the ‘RASCAL II’ meta-analysis[88]. Accordingly, the prognostic associations of KRAS mutations in colorectal cancer may vary by specific mutation. Considered in conjunction with evidence that KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations possess weaker transforming potential than codon 12 mutations[40], it may be the case that KRAS codon 61 or 146 mutation is not associated with patient prognosis. However, considering the limited case and event numbers for KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations, our survival analyses should be considered exploratory. Additional larger studies, perhaps necessitating pooling of data, are required to definitively assess the prognostic roles codon 61 and 146 mutations in colorectal cancer.

Several studies have examined the predictive value of KRAS mutation in codon 61 and/or 146 in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with anti-EGFR therapy (cetuximab or panitumumab)[26–28, 41, 43]. Pentheroudakis et al. did not observe any association between KRAS codon 61 or 146 mutation (N =11) and survival[41]. De Roock et al. showed that KRAS mutation in codon 61 (N =13), but not that in codon 146 (N =11), was significantly associated with lack of response to cetuximab[27]. Seymour et al. reported that KRAS codon 146 mutations (N =17) were not associated with overall or progression-free survival[43]. In contrast, Loupakis et al. reported that, among BRAF-wild-type cancers, KRAS codon 61 or 146 mutant cases (N = 8) experienced a significantly lower response rate and progression-free survival[26]. Indeed, a few experimental studies also reported that tumors harboring KRAS mutations in codons 61 and 146 were resistant to anti-EGFR therapy[28, 93]. In addition, a recent published study reported by Douillard et al., showed that RAS mutants (N = 108) with any mutation in KRAS codons 61, 117 and 146, or NRAS codons 12, 13, 61, 117 and 146, did not benefit from combined panitumumab plus FOLFOX4 chemotherapy[29]. In our dataset, due to scarcity of data on cancer treatment, we were unable to examine the important question of the predictive value of KRAS mutations in relation to anti-EGFR therapy. Further clinical studies in this area are clearly required.

The question arises as to whether it is worth investigating these relatively rare mutations in the clinical setting. Given that over 250,000 individuals each year die of colorectal cancer in Europe and the U.S., and most of these unfavorable outcomes are due to distant metastases, we estimate that every year approximately 10,000 cases have KRAS mutations in codon 61 or 146, and would be regarded as KRAS-wild-type through current KRAS codon 12 and 13 testing protocols. Considering that KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations may also confer resistance to EGFR inhibitors[26–29, 93], patients who have metastatic colorectal cancer with KRAS mutation in codon 61 or 146 could receive more tailored management through clinical testing of these additional KRAS codons.

A limitation of this study is the absence of data on KRAS codon 117 mutation and NRAS mutations. As a result, we could not refine purer RAS-wild-type (both KRAS- and NRAS-wild-type in codons 12, 13, 61, 117 and 146), or examine clinicopathological, molecular and prognostic features of those whole RAS mutations in this study. Considering that RAS mutations in those codons have been reported to predict lack of response to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer[29], further studies are necessary to answer important questions about features across various RAS mutants. Nonetheless, KRAS codons 61 and 146 are the most frequent mutational hotspots after KRAS codons 12 and 13. In addition, our current analysis (N>1200) represents a large single study to date (Additional file6: Table S6)[26–29, 32–74], examining KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations, in relation to other important molecular features in colorectal cancers, such as status of CIMP, MSI, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations. Sample size is a critical issue when assessing these relatively infrequent mutations. Indeed, smaller studies (N < 300, Additional file6: Table S6) demonstrate considerable variability in the frequencies and distribution of reported KRAS mutations, ranging from 0.4% to 9.3% for KRAS codon 61 mutations, and from 1.3% to 6.6% for KRAS codon 146 mutations (Additional file6: Table S6)[26–29, 32–74]. Given the relatively low frequencies of these mutations, a large sample size is a prerequisite for assessing the prevalence of these mutations and their associations with other tumor molecular characteristics.

There are advantages in utilizing the molecular pathological epidemiology[30, 31] database of the two U.S. nationwide prospective cohort studies to assess prevalence and associations of KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations. Selection bias is an inevitable issue when analyzing cases identified from a few academic hospitals, since patients have selected hospitals based on referral, health insurance applicability, and/or their own preference. In contrast, a large population-based or multicenter study is desirable to decrease the degree of such selection bias. In this study, cohort participants who were diagnosed with colorectal cancer were treated at hospitals throughout the U.S., and thus constitute a more representative sample of colorectal cancers in the U.S. population than patients in a few academic hospitals.

Conclusions

Our data from over 1200 colorectal cancers demonstrate that KRAS codon 61 or 146 hotspot mutations are present in approximately up to 5% of colorectal cancers, and those cancers exhibit similar clinicopathological and molecular features to cancers with KRAS codon 12 or 13 mutation. Our current findings suggest that additional large-scale studies are warranted to assess clinical utility of KRAS codon 61 and 146 testing in colorectal cancer.

Materials and methods

Study population

We utilized two prospective cohort studies, the Nurses’ Health Study (N = 121,701 women followed since 1976) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (N = 51,529 men followed since 1986)[16]. Every two years, cohort participants have been sent follow-up questionnaires to identify newly diagnosed cancers in themselves and their first degree relatives. The National Death Index was used to ascertain deaths of participants as well as unreported lethal cancers. The cause of death was assigned by study physicians. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were collected from hospitals where participants with colorectal cancer had undergone colorectal resection or diagnostic biopsy (for preoperatively-treated rectal cancers). We used 1267 colorectal cancer cases, diagnosed up to 2006, based on the availability of KRAS sequencing data. In order to examine the prognostic role of specific KRAS mutations, independent of BRAF mutation, BRAF-mutated cancers (N = 184), cases with missing BRAF mutation status (N = 5), and tumors with KRAS mutations identified in two or more of codons 12, 13, 61 and 146 (N = 11) were excluded. As a result, a final total of 1067 BRAF-wild-type cases were used for survival analyses (Figure 2, Additional file2: Table S2). Informed consent was obtained from all study subjects. This study was approved by the Human Subjects Committees at Harvard School of Public Health and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. All clinicopathological and molecular analyses were performed blinded to other data, including patient outcome.

Flow chart of the current study. Cases with BRAF mutation (N = 184) and those without available BRAF mutation data (N = 5), were excluded from survival analyses. In addition, cases with KRAS mutations identified in two or more of codons 12, 13, 61 and 146 (N = 11) were excluded, in order to assess a prognostic effect of specific KRAS mutations individually.

Histopathological evaluation

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of all cases were examined by a pathologist (SO) unaware of other data. Tumor differentiation was categorized as well-moderate or poor (>50% vs. ≤50% gland formation). Peritumoral lymphocytic reaction was examined as previously described[94].

Sequencing of KRAS codons 61 and 146

DNA was extracted from paraffin embedded tissue as previously described,[16] and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and pyrosequencing, targeted for KRAS codons 61 and 146, were performed. The PCR primers for amplifying KRAS codon 61 were, 5′-biotin-TGGAGAAACCTGTCTCTTGGATAT-3′ (for forward primer), and 5′-TACTGGTCCCTCATTGCACTGTA-3′ (for reverse primer), and those for KRAS codon 146 were 5′-ATGGAATTCCTTTTATTGAAACATC-3′ (for forward primer), and 5′-biotin-TTGCAGAAAACAGATCTGTATTTAT-3′(for reverse primer). The sequencing primers were 5′-TCATTGCACTGTACTCCTC-3′ (for codon 61), and 5′-AATTCCTTTTATTGAAACATCA-3′ (for codon 146). Dispensation orders were designed such that all possible mutations would be detected (Additional file7: Figure S1). All mutations were confirmed by replicate analysis.

Sequencing of KRAS codons 12 and 13, BRAF, and PIK3CA, and MSI analysis

We performed PCR and pyrosequencing targeted for KRAS (codons 12 and 13)[75], BRAF (codon 600) and PIK3CA (exons 9 and 20) as previously described[16]. MSI analysis was performed using 10 microsatellite markers (D2S123, D5S346, D17S250, BAT25, BAT26, BAT40, D18S55, D18S56, D18S67 and D18S487)[8]. MSI-high was defined as instability in ≥30% of the markers. MSI-low (<30% unstable markers) tumors were grouped with microsatellite stable (MSS) tumors (no unstable markers) because we have previously demonstrated that these two groups show similar features[8].

Methylation analyses for CpG islands and LINE-1

Using validated bisulfite DNA treatment and real-time PCR (MethyLight), we quantified DNA methylation in eight CIMP-specific promoters [CACNA1G, CDKN2A (p16), CRABP1, IGF2, MLH1, NEUROG1, RUNX3 and SOCS1][8]. CIMP-high was defined as the presence of ≥6/8 methylated promoters, CIMP-low as 1-5/8 methylated promoters, and CIMP-negative as the absence of methylated promoters, according to established criteria[8]. In order to accurately quantify LINE-1 methylation levels, we used bisulfite pyrosequencing as previously described[8].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All P-values were two-sided. Univariate analyses were performed to investigate clinicopathological and molecular characteristics according to KRAS mutation status; a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data, while a Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to continuous data (age and LINE-1 methylation). To account for multiple hypothesis testing in associations between KRAS mutation and other 14 covariates, the P-value for significance was adjusted by Bonferroni correction to P = 0.0036 (=0.05/14).

The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used to estimate survival distribution according to KRAS mutation status. Cases were observed until death, or January 1st 2011, whichever came first. For analyses of colorectal cancer-specific mortality, deaths as a result of other causes were censored. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to compute mortality HRs for specific KRAS mutations. A multivariate model initially included the following clinicopathological and molecular variables with less than 10% of patients showing missing information among those we have previously published; sex, age (continuous), BMI (<30 vs. ≥30 kg/m2), year of diagnosis (continuous), family history of colorectal cancer in any first-degree relative (present vs. absent), tumor location (cecum vs. ascending colon to sigmoid colon vs. rectum), tumor differentiation (well-moderate vs. poor), peritumoral lymphocytic reaction (absent-minimal vs. mild-marked), MSI (high vs. low/MSS), CIMP (high vs. low vs. negative), PIK3CA mutation (present vs. absent) and LINE-1 methylation (continuous), with stratification by disease stage (I, II, III, IV or unknown) was performed using the “strata” option in the SAS “proc phreg” command. A backward elimination was performed with a threshold of P = 0.20, to avoid overfitting. Cases with missing information for any of the categorical covariates [BMI (0.2%), tumor location (1.0%), tumor differentiation (0.7%), peritumoral lymphocytic reaction (4.6%), MSI (1.6%), CIMP (6.7%), and PIK3CA (7.6%)], were included in the majority category of the given covariate to avoid overfitting. We confirmed that excluding cases with missing information in any of the covariates did not substantially alter results (data not shown). To account for multiple hypothesis testing in associations between KRAS mutations and patient outcome, the P-value for significance was adjusted by Bonferroni correction to P = 0.025 [=0.05/2, for the two groups of codons (codons 12 and 13, and codons 61 and 146)], P = 0.013 (=0.05/4, for the four codons), or P = 0.005 (=0.05/10, for the 10 most common mutations). The proportionality of hazards assumption was satisfied by evaluating time-dependent variables, which were the cross products of the KRAS indicator variables and survival time (all P- values>0.07).

Literature search

A systematic literature search was performed in Pubmed, up to April 5, 2014, using combinations of the following search terms; KRAS, codon, (61 or 146), (colon, rectal or colorectal), and (cancer, carcinoma or adenocarcinoma). All eligible publications were retrieved, and their references were checked to identify further relevant studies. In addition, we contacted some corresponding authors to obtain detailed data.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CIMP:

-

CpG island methylator phenotype

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- MSI:

-

Microsatellite instability

- MSS:

-

Microsatellite stable

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PI3K:

-

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphonate 3-kinase.

References

Lao VV, Grady WM: Epigenetics and colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011, 8: 686-700. 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.173

Febbo PG, Ladanyi M, Aldape KD, De Marzo AM, Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Iafrate AJ, Kelley RK, Marcucci G, Ogino S, Pao W, Sgroi DC, Birkeland ML: NCCN Task Force report: evaluating the clinical utility of tumor markers in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011, 9 (Suppl 5): S1-S32.

Colussi D, Brandi G, Bazzoli F, Ricciardiello L: Molecular pathways involved in colorectal cancer: implications for disease behavior and prevention. Int J Mol Sci. 2013, 14: 16365-16385. 10.3390/ijms140816365

Bardhan K, Liu K: Epigenetics and colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Cancers. 2013, 5: 676-713. 10.3390/cancers5020676

Rosty C, Young JP, Walsh MD, Clendenning M, Walters RJ, Pearson S, Pavluk E, Nagler B, Pakenas D, Jass JR, Jenkins MA, Win AK, Southey MC, Parry S, Hopper JL, Giles GG, Williamson E, English DR, Buchanan DD: Colorectal carcinomas with KRAS mutation are associated with distinctive morphological and molecular features. Mod Pathol. 2013, 26: 825-834. 10.1038/modpathol.2012.240

Day FL, Jorissen RN, Lipton L, Mouradov D, Sakthianandeswaren A, Christie M, Li S, Tsui C, Tie J, Desai J, Xu ZZ, Molloy P, Whitehall V, Leggett BA, Jones IT, McLaughlin S, Ward RL, Hawkins NJ, Ruszkiewicz AR, Moore J, Busam D, Zhao Q, Strausberg RL, Gibbs P, Sieber OM: PIK3CA and PTEN gene and exon mutation-specific clinicopathologic and molecular associations in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013, 19: 3285-3296. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3614

Eklof V, Wikberg ML, Edin S, Dahlin AM, Jonsson BA, Oberg A, Rutegard J, Palmqvist R: The prognostic role of KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and PTEN in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013, 108: 2153-2163. 10.1038/bjc.2013.212

Yamauchi M, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Imamura Y, Qian ZR, Nishihara R, Liao X, Waldron L, Hoshida Y, Huttenhower C, Chan AT, Giovannucci E, Fuchs C, Ogino S: Assessment of colorectal cancer molecular features along bowel subsites challenges the conception of distinct dichotomy of proximal versus distal colorectum. Gut. 2012, 61: 847-854. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300865

Wangefjord S, Sundstrom M, Zendehrokh N, Lindquist KE, Nodin B, Jirstrom K, Eberhard J: Sex differences in the prognostic significance of KRAS codons 12 and 13, and BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer: a cohort study. Biol Sex Differ. 2013, 4: 17- 10.1186/2042-6410-4-17

Hinoue T, Weisenberger DJ, Lange CP, Shen H, Byun HM, Van Den Berg D, Malik S, Pan F, Noushmehr H, van Dijk CM, Tollenaar RA, Laird PW: Genome-scale analysis of aberrant DNA methylation in colorectal cancer. Genome Res. 2012, 22: 271-282. 10.1101/gr.117523.110

Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, Loda M, Fuchs CS: CpG island methylator phenotype-low (CIMP-low) in colorectal cancer: possible associations with male sex and KRAS mutations. J Mol Diagn. 2006, 8: 582-588. 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.060082

Kim JH, Shin SH, Kwon HJ, Cho NY, Kang GH: Prognostic implications of CpG island hypermethylator phenotype in colorectal cancers. Virchows Arch. 2009, 455: 485-494. 10.1007/s00428-009-0857-0

Barault L, Charon-Barra C, Jooste V, de la Vega MF, Martin L, Roignot P, Rat P, Bouvier AM, Laurent-Puig P, Faivre J, Chapusot C, Piard F: Hypermethylator phenotype in sporadic colon cancer: study on a population-based series of 582 cases. Cancer Res. 2008, 68: 8541-8546. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1171

Dahlin AM, Palmqvist R, Henriksson ML, Jacobsson M, Eklof V, Rutegard J, Oberg A, Van Guelpen BR: The role of the CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer prognosis depends on microsatellite instability screening status. Clin Cancer Res. 2010, 16: 1845-1855. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2594

Whitehall VL, Rickman C, Bond CE, Ramsnes I, Greco SA, Umapathy A, McKeone D, Faleiro RJ, Buttenshaw RL, Worthley DL, Nayler S, Zhao ZZ, Montgomery GW, Mallitt KA, Jass JR, Matsubara N, Notohara K, Ishii T, Leggett BA: Oncogenic PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancers and polyps. Int J Cancer. 2012, 131: 813-820. 10.1002/ijc.26440

Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, Imamura Y, Qian ZR, Baba Y, Shima K, Sun R, Nosho K, Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS, Chan AT, Ogino S: Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. N Engl J Med. 2012, 367: 1596-1606. 10.1056/NEJMoa1207756

De Roock W, De Vriendt V, Normanno N, Ciardiello F, Tejpar S: KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, and PTEN mutations: implications for targeted therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12: 594-603. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70209-6

He Y, Van’t Veer LJ, Mikolajewska-Hanclich I, van Velthuysen ML, Zeestraten EC, Nagtegaal ID, van de Velde CJ, Marijnen CA: PIK3CA mutations predict local recurrences in rectal cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009, 15: 6956-6962. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1165

Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Lang I, Folprecht G, Nowacki MP, Cascinu S, Shchepotin I, Maurel J, Cunningham D, Tejpar S, Schlichting M, Zubel A, Celik I, Rougier P, Ciardiello F: Cetuximab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: updated analysis of overall survival according to tumor KRAS and BRAF mutation status. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29: 2011-2019. 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5091

Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, Hartmann JT, Aparicio J, de Braud F, Donea S, Ludwig H, Schuch G, Stroh C, Loos AH, Zubel A, Koralewski P: Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27: 663-671. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8397

Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, Humblet Y, Bodoky G, Cunningham D, Jassem J, Rivera F, Kocakova I, Ruff P, Blasinska-Morawiec M, Smakal M, Canon JL, Rother M, Oliner KS, Wolf M, Gansert J: Randomized, phase III trial of panitumumab with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) versus FOLFOX4 alone as first-line treatment in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: the PRIME study. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28: 4697-4705. 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4860

Custodio A, Feliu J: Prognostic and predictive biomarkers for epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy in colorectal cancer: beyond KRAS mutations. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013, 85: 45-81. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.05.001

Reimers MS, Zeestraten ECM, Kuppen PJK, Liefers GJ, Velde CJH: Biomarkers in precision therapy in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Rep. 2013, 1: 166-183. 10.1093/gastro/got022.

De Roock W, Jonker DJ, Di Nicolantonio F, Sartore-Bianchi A, Tu D, Siena S, Lamba S, Arena S, Frattini M, Piessevaux H, Van Cutsem E, O’Callaghan CJ, Khambata-Ford S, Zalcberg JR, Simes J, Karapetis CS, Bardelli A, Tejpar S: Association of KRAS p.G13D mutation with outcome in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. JAMA. 2010, 304: 1812-1820. 10.1001/jama.2010.1535

Tejpar S, Celik I, Schlichting M, Sartorius U, Bokemeyer C, Van Cutsem E: Association of KRAS G13D tumor mutations with outcome in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with first-line chemotherapy with or without cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 30: 3570-3577. 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.2592

Loupakis F, Ruzzo A, Cremolini C, Vincenzi B, Salvatore L, Santini D, Masi G, Stasi I, Canestrari E, Rulli E, Floriani I, Bencardino K, Galluccio N, Catalano V, Tonini G, Magnani M, Fontanini G, Basolo F, Falcone A, Graziano F: KRAS codon 61, 146 and BRAF mutations predict resistance to cetuximab plus irinotecan in KRAS codon 12 and 13 wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009, 101: 715-721. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605177

De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D, De Schutter J, Biesmans B, Fountzilas G, Kalogeras KT, Kotoula V, Papamichael D, Laurent-Puig P, Penault-Llorca F, Rougier P, Vincenzi B, Santini D, Tonini G, Cappuzzo F, Frattini M, Molinari F, Saletti P, De Dosso S, Martini M, Bardelli A, Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Tabernero J, Macarulla T, Di Fiore F, Gangloff AO, Ciardiello F, Pfeiffer P: Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11: 753-762. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70130-3

Janakiraman M, Vakiani E, Zeng Z, Pratilas CA, Taylor BS, Chitale D, Halilovic E, Wilson M, Huberman K, Ricarte Filho JC, Persaud Y, Levine DA, Fagin JA, Jhanwar SC, Mariadason JM, Lash A, Ladanyi M, Saltz LB, Heguy A, Paty PB, Solit DB: Genomic and biological characterization of exon 4 KRAS mutations in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2010, 70: 5901-5911. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0192

Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, Humblet Y, Bodoky G, Cunningham D, Jassem J, Rivera F, Kocakova I, Ruff P, Blasinska-Morawiec M, Smakal M, Canon JL, Rother M, Williams R, Rong A, Wiezorek J, Sidhu R, Patterson SD: Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013, 369: 1023-1034. 10.1056/NEJMoa1305275

Ogino S, Chan AT, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci E: Molecular pathological epidemiology of colorectal neoplasia: an emerging transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary field. Gut. 2011, 60: 397-411. 10.1136/gut.2010.217182

Ogino S, Stampfer M: Lifestyle factors and microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer: the evolving field of molecular pathological epidemiology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010, 102: 365-367. 10.1093/jnci/djq031

Tong JH, Lung RW, Sin FM, Law PP, Kang W, Chan AW, Ma BB, Mak TW, Ng SS, To KF: Characterization of rare transforming mutations in sporadic colorectal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. in press,

Vaughn CP, Zobell SD, Furtado LV, Baker CL, Samowitz WS: Frequency of KRAS, BRAF, and NRAS mutations in colorectal cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011, 50: 307-312. 10.1002/gcc.20854

The Cancer Genome Atlas Network: Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012, 487: 330-337. 10.1038/nature11252

Gaedcke J, Grade M, Jung K, Schirmer M, Jo P, Obermeyer C, Wolff HA, Herrmann MK, Beissbarth T, Becker H, Ried T, Ghadimi M: KRAS and BRAF mutations in patients with rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2010, 94: 76-81. 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.10.001

Chang YS, Yeh KT, Chang TJ, Chai C, Lu HC, Hsu NC, Chang JG: Fast simultaneous detection of K-RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009, 9: 179- 10.1186/1471-2407-9-179

Vakiani E, Janakiraman M, Shen R, Sinha R, Zeng Z, Shia J, Cercek A, Kemeny N, D’Angelica M, Viale A, Heguy A, Paty P, Chan TA, Saltz LB, Weiser M, Solit DB: Comparative genomic analysis of primary versus metastatic colorectal carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 30: 2956-2962. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.2994

Bando H, Yoshino T, Shinozaki E, Nishina T, Yamazaki K, Yamaguchi K, Yuki S, Kajiura S, Fujii S, Yamanaka T, Tsuchihara K, Ohtsu A: Simultaneous identification of 36 mutations in KRAS codons 61and 146, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA in a single reaction by multiplex assay kit. BMC Cancer. 2013, 13: 405- 10.1186/1471-2407-13-405

Edkins S, O’Meara S, Parker A, Stevens C, Reis M, Jones S, Greenman C, Davies H, Dalgliesh G, Forbes S, Hunter C, Smith R, Stephens P, Goldstraw P, Nicholson A, Chan TL, Velculescu VE, Yuen ST, Leung SY, Stratton MR, Futreal PA: Recurrent KRAS codon 146 mutations in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006, 5: 928-932. 10.4161/cbt.5.8.3251

Smith G, Bounds R, Wolf H, Steele RJ, Carey FA, Wolf CR: Activating K-Ras mutations outwith ‘hotspot’ codons in sporadic colorectal tumours - implications for personalised cancer medicine. Br J Cancer. 2010, 102: 693-703. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605534

Pentheroudakis G, Kotoula V, De Roock W, Kouvatseas G, Papakostas P, Makatsoris T, Papamichael D, Xanthakis I, Sgouros J, Televantou D, Kafiri G, Tsamandas AC, Razis E, Galani E, Bafaloukos D, Efstratiou I, Bompolaki I, Pectasides D, Pavlidis N, Tejpar S, Fountzilas G: Biomarkers of benefit from cetuximab-based therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: interaction of EGFR ligand expression with RAS/RAF, PIK3CA genotypes. BMC Cancer. 2013, 13: 49- 10.1186/1471-2407-13-49

Fadhil W, Ibrahem S, Seth R, AbuAli G, Ragunath K, Kaye P, Ilyas M: The utility of diagnostic biopsy specimens for predictive molecular testing in colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 2012, 61: 1117-1124. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04321.x

Seymour MT, Brown SR, Middleton G, Maughan T, Richman S, Gwyther S, Lowe C, Seligmann JF, Wadsley J, Maisey N, Chau I, Hill M, Dawson L, Falk S, O’Callaghan A, Benstead K, Chambers P, Oliver A, Marshall H, Napp V, Quirke P: Panitumumab and irinotecan versus irinotecan alone for patients with KRAS wild-type, fluorouracil-resistant advanced colorectal cancer (PICCOLO): a prospectively stratified randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14: 749-759. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70163-3

Kosmidou V, Oikonomou E, Vlassi M, Avlonitis S, Katseli A, Tsipras I, Mourtzoukou D, Kontogeorgos G, Zografos G, Pintzas A: Tumor heterogeneity revealed by KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA pyrosequencing: KRAS and PIK3CA intratumor mutation profile differences and their therapeutic implications. Hum Mutat. 2014, 35: 329-340. 10.1002/humu.22496

Richman SD, Seymour MT, Chambers P, Elliott F, Daly CL, Meade AM, Taylor G, Barrett JH, Quirke P: KRAS and BRAF mutations in advanced colorectal cancer are associated with poor prognosis but do not preclude benefit from oxaliplatin or irinotecan: results from the MRC FOCUS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27: 5931-5937. 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4295

Shen Y, Wang J, Han X, Yang H, Wang S, Lin D, Shi Y: Effectors of epidermal growth factor receptor pathway: the genetic profiling ofKRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, NRAS mutations in colorectal cancer characteristics and personalized medicine. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e81628- 10.1371/journal.pone.0081628

Wang J, Yang H, Shen Y, Wang S, Lin D, Ma L, Han X, Shi Y: Direct sequencing is a reliable assay with good clinical applicability for KRAS mutation testing in colorectal cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2013, 13: 89-97.

Peeters M, Oliner KS, Parker A, Siena S, Van Cutsem E, Huang J, Humblet Y, Van Laethem JL, Andre T, Wiezorek J, Reese D, Patterson SD: Massively parallel tumor multigene sequencing to evaluate response to panitumumab in a randomized phase III study of metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013, 19: 1902-1912. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1913

Fumagalli D, Gavin PG, Taniyama Y, Kim SI, Choi HJ, Paik S, Pogue-Geile KL: A rapid, sensitive, reproducible and cost-effective method for mutation profiling of colon cancer and metastatic lymph nodes. BMC Cancer. 2010, 10: 101- 10.1186/1471-2407-10-101

Chaiyapan W, Duangpakdee P, Boonpipattanapong T, Kanngern S, Sangkhathat S: Somatic mutations of K-Ras and BRAF in Thai colorectal cancer and their prognostic value. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013, 14: 329-332. 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.1.329

Sundstrom M, Edlund K, Lindell M, Glimelius B, Birgisson H, Micke P, Botling J: KRAS analysis in colorectal carcinoma: analytical aspects of Pyrosequencing and allele-specific PCR in clinical practice. BMC Cancer. 2010, 10: 660- 10.1186/1471-2407-10-660

Lurkin I, Stoehr R, Hurst CD, van Tilborg AA, Knowles MA, Hartmann A, Zwarthoff EC: Two multiplex assays that simultaneously identify 22 possible mutation sites in the KRAS, BRAF, NRAS and PIK3CA genes. PLoS One. 2010, 5: e8802- 10.1371/journal.pone.0008802

Kim MJ, Lee HS, Kim JH, Kim YJ, Kwon JH, Lee JO, Bang SM, Park KU, Kim DW, Kang SB, Kim JS, Lee JS, Lee KW: Different metastatic pattern according to the KRAS mutational status and site-specific discordance of KRAS status in patients with colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012, 12: 347- 10.1186/1471-2407-12-347

Netzel BC, Grebe SK: Companion-diagnostic testing limited to KRAS codons 12 and 13 misses 17% of potentially relevant RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2013, 425C: 1-2.

Molinari F, Felicioni L, Buscarino M, De Dosso S, Buttitta F, Malatesta S, Movilia A, Luoni M, Boldorini R, Alabiso O, Girlando S, Soini B, Spitale A, Di Nicolantonio F, Saletti P, Crippa S, Mazzucchelli L, Marchetti A, Bardelli A, Frattini M: Increased detection sensitivity for KRAS mutations enhances the prediction of anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody resistance in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011, 17: 4901-4914. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3137

Kim SY, Shim EK, Yeo HY, Baek JY, Hong YS, Kim DY, Kim TW, Kim JH, Im SA, Jung KH, Chang HJ: KRAS mutation status and clinical outcome of preoperative chemoradiation with cetuximab in locally advanced rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 2 phase II trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013, 85: 201-207. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.048

Andre T, Blons H, Mabro M, Chibaudel B, Bachet JB, Tournigand C, Bennamoun M, Artru P, Nguyen S, Ebenezer C, Aissat N, Cayre A, Penault-Llorca F, Laurent-Puig P, de Gramont A: Gercor. Panitumumab combined with irinotecan for patients with KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard chemotherapy: a GERCOR efficacy, tolerance, and translational molecular study. Ann Oncol. 2013, 24: 412-419. 10.1093/annonc/mds465

Lewandowska MA, Jozwicki W, Zurawski B: KRAS and BRAF mutation analysis in colorectal adenocarcinoma specimens with a low percentage of tumor cells. Mol Diagn Ther. 2013, 17: 193-203. 10.1007/s40291-013-0025-8

Winder T, Mundlein A, Rhomberg S, Dirschmid K, Hartmann BL, Knauer M, Drexel H, Wenzl E, De Vries A, Lang A: Different types of K-Ras mutations are conversely associated with overall survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2009, 21: 1283-1287.

Bishehsari F, Mahdavinia M, Malekzadeh R, Verginelli F, Catalano T, Sotoudeh M, Bazan V, Agnese V, Esposito DL, De Lellis L, Semeraro D, Colucci G, Hormazdi M, Rakhshani N, Cama A, Piantelli M, Iacobelli S, Russo A, Mariani-Costantini R: Patterns of K-ras mutation in colorectal carcinomas from Iran and Italy (a Gruppo Oncologico dell’Italia Meridionale study): influence of microsatellite instability status and country of origin. Ann Oncol. 2006, 17 (Suppl 7): vii91-vii96.

Luna-Perez P, Segura J, Alvarado I, Labastida S, Santiago-Payan H, Quintero A: Specific c-K-ras gene mutations as a tumor-response marker in locally advanced rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000, 7: 727-731. 10.1007/s10434-000-0727-0

Servomaa K, Kiuru A, Kosma VM, Hirvikoski P, Rytomaa T: p53 and K-ras gene mutations in carcinoma of the rectum among Finnish women. Mol Pathol. 2000, 53: 24-30. 10.1136/mp.53.1.24

Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Kern SE, Preisinger AC, Leppert M, Nakamura Y, White R, Smits AM, Bos JL: Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med. 1988, 319: 525-532. 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901

Poehlmann A, Kuester D, Meyer F, Lippert H, Roessner A, Schneider-Stock R: K-ras mutation detection in colorectal cancer using the Pyrosequencing technique. Pathol Res Pract. 2007, 203: 489-497. 10.1016/j.prp.2007.06.001

Bos JL, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Verlaan-de Vries M, van Boom JH, van der Eb AJ, Vogelstein B: Prevalence of ras gene mutations in human colorectal cancers. Nature. 1987, 327: 293-297. 10.1038/327293a0

Shen H, Yuan Y, Hu HG, Zhong X, Ye XX, Li MD, Fang WJ, Zheng S: Clinical significance of K-ras and BRAF mutations in Chinese colorectal cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2011, 17: 809-816. 10.3748/wjg.v17.i6.809

Wistuba II, Behrens C, Albores-Saavedra J, Delgado R, Lopez F, Gazdar AF: Distinct K-ras mutation pattern characterizes signet ring cell colorectal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003, 9: 3615-3619.

Stefanius K, Ylitalo L, Tuomisto A, Kuivila R, Kantola T, Sirnio P, Karttunen TJ, Makinen MJ: Frequent mutations of KRAS in addition to BRAF in colorectal serrated adenocarcinoma. Histopathology. 2011, 58: 679-692. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03821.x

Ozen F, Ozdemir S, Zemheri E, Hacimuto G, Silan F, Ozdemir O: The proto-oncogene KRAS and BRAF profiles and some clinical characteristics in colorectal cancer in the Turkish population. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2013, 17: 135-139. 10.1089/gtmb.2012.0290

Delord JP, Tabernero J, Garcia-Carbonero R, Cervantes A, Gomez-Roca C, Berge Y, Capdevila J, Paz-Ares L, Roda D, Delmar P, Oppenheim D, Brossard SS, Farzaneh F, Manenti L, Passioukov A, Ott MG, Soria JC: Open-label, multicentre expansion cohort to evaluate imgatuzumab in pre-treated patients with KRAS-mutant advanced colorectal carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2014, 50: 496-505. 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.10.015

Tian S, Simon I, Moreno V, Roepman P, Tabernero J, Snel M, Van’t Veer L, Salazar R, Bernards R, Capella G: A combined oncogenic pathway signature of BRAF, KRAS and PI3KCA mutation improves colorectal cancer classification and cetuximab treatment prediction. Gut. 2013, 62: 540-549. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302423

Oliveira C, Westra JL, Arango D, Ollikainen M, Domingo E, Ferreira A, Velho S, Niessen R, Lagerstedt K, Alhopuro P, Laiho P, Veiga I, Teixeira MR, Ligtenberg M, Kleibeuker JH, Sijmons RH, Plukker JT, Imai K, Lage P, Hamelin R, Albuquerque C, Schwartz S, Lindblom A, Peltomaki P, Yamamoto H, Aaltonen LA, Seruca R, Hofstra RM: Distinct patterns of KRAS mutations in colorectal carcinomas according to germline mismatch repair defects and hMLH1 methylation status. Hum Mol Genet. 2004, 13: 2303-2311. 10.1093/hmg/ddh238

Harle A, Busser B, Rouyer M, Harter V, Genin P, Leroux A, Merlin JL: Comparison of COBAS 4800 KRAS, TaqMan PCR and high resolution melting PCR assays for the detection of KRAS somatic mutations in formalin-fixed paraffin embedded colorectal carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2013, 462: 329-335. 10.1007/s00428-013-1380-x

Richman SD, Chambers P, Seymour MT, Daly C, Grant S, Hemmings G, Quirke P: Intra-tumoral heterogeneity of KRAS and BRAF mutation status in patients with advanced colorectal cancer (aCRC) and cost-effectiveness of multiple sample testing. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst). 2011, 34: 61-66.

Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Brahmandam M, Yan L, Cantor M, Namgyal C, Mino-Kenudson M, Lauwers GY, Loda M, Fuchs CS: Sensitive sequencing method for KRAS mutation detection by Pyrosequencing. J Mol Diagn. 2005, 7: 413-421. 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60571-5

Kostic AD, Gevers D, Pedamallu CS, Michaud M, Duke F, Earl AM, Ojesina AI, Jung J, Bass AJ, Tabernero J, Baselga J, Liu C, Shivdasani RA, Ogino S, Birren BW, Huttenhower C, Garrett WS, Meyerson M: Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012, 22: 292-298. 10.1101/gr.126573.111

Gaur S, Chen L, Ann V, Lin WC, Wang Y, Chang VH, Hsu NY, Shia HS, Yen Y: Dovitinib synergizes with oxaliplatin in suppressing cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells regardless of RAS-RAF mutation status. Mol Cancer. 2014, 13: 21- 10.1186/1476-4598-13-21

Duan FT, Qian F, Fang K, Lin KY, Wang WT, Chen YQ: miR-133b, a muscle-specific microRNA, is a novel prognostic marker that participates in the progression of human colorectal cancer via regulation of CXCR4 expression. Mol Cancer. 2013, 12: 164- 10.1186/1476-4598-12-164

Guo H, Chen Y, Hu X, Qian G, Ge S, Zhang J: The regulation of Toll-like receptor 2 by miR-143 suppresses the invasion and migration of a subset of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2013, 12: 77- 10.1186/1476-4598-12-77

Wu W, Yang J, Feng X, Wang H, Ye S, Yang P, Tan W, Wei G, Zhou Y: MicroRNA-32 (miR-32) regulates phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) expression and promotes growth, migration, and invasion in colorectal carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2013, 12: 30- 10.1186/1476-4598-12-30

Zoratto F, Rossi L, Verrico M, Papa A, Basso E, Zullo A, Tomao L, Romiti A, Russo G, Tomao S: Focus on genetic and epigenetic events of colorectal cancer pathogenesis: implications for molecular diagnosis. Tumour Biol. 2014, doi:10.1007/s13277-014-1845-9,

Yoon HH, Tougeron D, Shi Q, Alberts SR, Mahoney MR, Nelson GD, Nair SG, Thibodeau SN, Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Sinicrope FA: KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations in relation to disease-free survival in BRAF-wild type stage III colon cancers from an adjuvant chemotherapy trial (N0147 Alliance). Clin Cancer Res. 2014, in press,

Tougeron D, Sha D, Manthravadi S, Sinicrope FA: Aspirin and colorectal cancer: back to the future. Clin Cancer Res. 2014, 20: 1087-1094. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2563

Kim A, Lee JE, Lee SS, Kim C, Lee SJ, Jang WS, Park S: Coexistent mutations of KRAS and PIK3CA affect the efficacy of NVP-BEZ235, a dual PI3K/MTOR inhibitor, in regulating the PI3K/MTOR pathway in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013, 133: 984-996. 10.1002/ijc.28073

Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Nosho K, Ohnishi M, Suemoto Y, Kirkner GJ, Fuchs CS: LINE-1 hypomethylation is inversely associated with microsatellite instability and CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008, 122: 2767-2773. 10.1002/ijc.23470

Bollag G, McCormick F: Intrinsic and GTPase-activating protein-stimulated Ras GTPase assays. Methods Enzymol. 1995, 255: 161-170.

John J, Frech M, Wittinghofer A: Biochemical properties of Ha-ras encoded p21 mutants and mechanism of the autophosphorylation reaction. J Biol Chem. 1988, 263: 11792-11799.

Andreyev HJ, Norman AR, Cunningham D, Oates J, Dix BR, Iacopetta BJ, Young J, Walsh T, Ward R, Hawkins N, Beranek M, Jandik P, Benamouzig R, Jullian E, Laurent-Puig P, Olschwang S, Muller O, Hoffmann I, Rabes HM, Zietz C, Troungos C, Valavanis C, Yuen ST, Ho JW, Croke CT, O’Donoghue DP, Giaretti W, Rapallo A, Russo A, Bazan V: Kirsten ras mutations in patients with colorectal cancer: the ‘RASCAL II’ study. Br J Cancer. 2001, 85: 692-696. 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1964

Ogino S, Meyerhardt JA, Irahara N, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Schaefer P, Whittom R, Hantel A, Benson AB, Goldberg RM, Bertagnolli MM, Fuchs CS, : KRAS mutation in stage III colon cancer and clinical outcome following intergroup trial CALGB 89803. Clin Cancer Res. 2009, 15: 7322-7329. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1570

Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, Yan P, Fiocca R, Klingbiel D, Dietrich D, Biesmans B, Bodoky G, Barone C, Aranda E, Nordlinger B, Cisar L, Labianca R, Cunningham D, Van Cutsem E, Bosman F: Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60–00 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28: 466-474. 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3452

Hutchins G, Southward K, Handley K, Magill L, Beaumont C, Stahlschmidt J, Richman S, Chambers P, Seymour M, Kerr D, Gray R, Quirke P: Value of mismatch repair, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in predicting recurrence and benefits from chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29: 1261-1270. 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1366

Phipps AI, Buchanan DD, Makar KW, Win AK, Baron JA, Lindor NM, Potter JD, Newcomb PA: KRAS-mutation status in relation to colorectal cancer survival: the joint impact of correlated tumour markers. Br J Cancer. 2013, 108: 1757-1764. 10.1038/bjc.2013.118

Messner I, Cadeddu G, Huckenbeck W, Knowles HJ, Gabbert HE, Baldus SE, Schaefer KL: KRAS p.G13D mutations are associated with sensitivity to anti-EGFR antibody treatment in colorectal cancer cell lines. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013, 139: 201-209. 10.1007/s00432-012-1319-7

Ogino S, Nosho K, Irahara N, Meyerhardt JA, Baba Y, Shima K, Glickman JN, Ferrone CR, Mino-Kenudson M, Tanaka N, Dranoff G, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS: Lymphocytic reaction to colorectal cancer is associated with longer survival, independent of lymph node count, microsatellite instability, and CpG island methylator phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2009, 15: 6412-6420. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1438

Acknowledgments

We deeply thank hospitals and pathology departments throughout the U.S. for generously providing us with tissue specimens. In addition, we would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. This work was supported by U.S. National Institute of Health (NIH) grants [P01 CA87969 to S.E. Hankinson; P01 CA55075 to W.C. Willett; UM1 CA167552 to W.C. Willett; P50 CA127003 to CSF; R01 CA137178 to ATC; and R01 CA151993 to SO]; and by grants from the Bennett Family Fund and the Entertainment Industry Foundation through National Colorectal Cancer Research Alliance. ATC is a Damon Runyon Clinical Investigator. PL is a Scottish Government Clinical Academic Fellow and was supported by a Harvard University Frank Knox Memorial Fellowship. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

ATC previously served as a consultant for Bayer Healthcare, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer Inc. This study was not funded by Bayer Healthcare, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, or Pfizer Inc. No other conflict of interest exists.

Authors’ contributions

YI, SO and KMH conceived of the study. YI, PL, MY, ZRQ, XL and KN carried out molecular analysis. YI and SO interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. AK, RN, SJ, KW, YEW, SP and AJB helped the statistical analysis and participated in interpretation of data. JAM, ATC and CSF helped to draft the manuscript, and participated in interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Yu Imamura, Paul Lochhead, Mai Yamauchi, Aya Kuchiba, Andrew T Chan, Charles S Fuchs and Shuji Ogino contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12943_2014_1334_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Table S1: Clinicopathological, and molecular characteristics of KRAS-wild-type, only-one-KRAS-codon mutated, or two-or-more-KRAS-codons mutated cases. (DOC 134 KB)

12943_2014_1334_MOESM2_ESM.doc

Additional file 2: Table S2: Clinicopathological, and molecular characteristics according to KRAS mutation status in 1067 BRAF-wild-type cases. (DOC 136 KB)

12943_2014_1334_MOESM3_ESM.doc

Additional file 3: Table S3: Clinicopathological features of 51 KRAS codon 61 or 146 mutated cases in 1067 BRAF-wild-type cases. (DOC 174 KB)

12943_2014_1334_MOESM4_ESM.doc

Additional file 4: Table S4: Stage I-II, BRAF-wild-type colorectal cancer patient mortality according to KRAS mutation status. (DOC 135 KB)

12943_2014_1334_MOESM5_ESM.doc

Additional file 5: Table S5: Stage III-IV, BRAF-wild-type colorectal cancer patient mortality according to KRAS mutation status. (DOC 135 KB)

12943_2014_1334_MOESM6_ESM.doc

Additional file 6: Table S6: Previous studies examining KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations in colorectal cancer. (DOC 188 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Imamura, Y., Lochhead, P., Yamauchi, M. et al. Analyses of clinicopathological, molecular, and prognostic associations of KRAS codon 61 and codon 146 mutations in colorectal cancer: cohort study and literature review. Mol Cancer 13, 135 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-13-135

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-13-135