Abstract

Background

Activating KRAS and BRAF mutations predict unresponsiveness to EGFR-targeting therapies in colorectal cancer (CRC), but their prognostic value needs further validation. In this study, we investigated the impact of KRAS codons 12 and 13, and BRAF mutations on survival from CRC, overall and stratified by sex, in a large prospective cohort study.

Methods

KRAS codons 12 and 13, and BRAF mutations were analysed by pyrosequencing of tumours from 525 and 524 incident CRC cases in The Malmö Diet and Cancer Study. Associations with cancer-specific survival (CSS) were explored by Cox proportional hazards regression, unadjusted and adjusted for age, TNM stage, differentiation grade, vascular invasion and microsatellite instability (MSI) status.

Results

KRAS and BRAF mutations were mutually exclusive. KRAS mutations were found in 191/ 525 (36.4%) cases, 82.2% of these mutations were in codon 12, 17.3% were in codon 13, and 0.5% cases had mutations in both codons. BRAF mutations were found in 78/524 (14.9%) cases. Overall, mutation in KRAS codon 13, but not codon 12, was associated with a significantly reduced CSS in unadjusted, but not in adjusted analysis, and BRAF mutation did not significantly affect survival. However, in microsatellite stable (MSS), but not in MSI tumours, an adverse prognostic impact of BRAF mutation was observed in unadjusted, but not in adjusted analysis. While KRAS mutation status was not significantly associated with sex, BRAF mutations were more common in women. BRAF mutation was not prognostic in women; but in men, BRAF mutation was associated with a significantly reduced CSS in overall adjusted analysis (HR = 3.50; 95% CI = 1.41–8.70), but not in unadjusted analysis. In men with MSS tumours, BRAF mutation was an independent factor of poor prognosis (HR = 4.91; 95% CI = 1.99–12.12). KRAS codon 13 mutation was associated with a significantly reduced CSS in women, but not in men in unadjusted, but not in adjusted analysis.

Conclusions

Results from this cohort study demonstrate sex-related differences in the prognostic value of BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer, being particularly evident in men. These findings are novel and merit further validation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The successful treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC) relies on an early diagnosis, radical surgery and adequate adjuvant treatment. Presently, tumour stage at diagnosis is the most important prognostic factor. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that CRC is a highly heterogeneous disease with different genetic and molecular characteristics affecting intrinsic tumour aggressiveness, response to systemic treatment, and, hence, clinical outcome. Although many efforts have been made to find biomarkers to more accurately predict high-risk disease and to select patients for adjuvant treatment, none have proven good enough for use in clinical routine.

Activating mutations of proto-oncogenes KRAS and BRAF are common in CRC, causing unregulated downstream signalling in the Ras/Raf/MEK/MAP signal transduction pathway, in turn, affecting a variety of cellular responses such as proliferation, differentiation, migration, survival and apoptosis [1]. Approximately 40% of all colorectal tumours harbour a KRAS mutation, predominantly occurring in codon 12 or 13 [2]. While KRAS mutation has proven to be predictive of the resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-inhibiting therapies [3, 4], the prognostic value of KRAS mutation in CRC remains unclear. Numerous studies have investigated the relationship between KRAS mutation status and survival from CRC with divergent results; however, the majority of them are associating KRAS mutation with a poor prognosis [5–11]. Notably, while most studies did not consider specific mutations, accumulating evidence indicates that specific codon 12 and 13 mutations have a stronger impact on the functionality of the KRAS protein, and, hence, its impact on clinical outcome in CRC patients [5, 12, 13].

BRAF mutations have been reported in CRC at a frequency of 5%–18% with the vast majority being a V600E substitution [14]. BRAF mutation has also been linked to an impaired prognosis in CRC [9, 15, 16] and unresponsiveness to anti-EGFR drugs [17–19]. BRAF and KRAS mutations are, with rare exceptions, mutually exclusive [20].

The prognostic value of clinicopathological factors [21, 22] and investigative biomarkers [23] may well differ in men and women, but to our best knowledge, no previous studies have investigated sex-related differences in the prognostic impact of KRAS and BRAF mutation in CRC. In the present study, we examined the associations of specific KRAS and BRAF mutations with clinicopathological and tumour biological characteristics, and survival, in 525 incident cases of colorectal cancer from a prospective population-based cohort study.

Methods

Study population

Until the end of follow-up in 31 December 2008, 626 incident cases of CRC had been registered in the prospective population-based cohort from the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study (MDCS) [22, 24]. Patient and tumour characteristics of the cohort have been described in detail previously [23, 25–27]. Ethical permission was obtained from the Ethics Committee at Lund University. Tissue microarrays have been constructed from 557 cases as previously described [23, 25]. Immunohistochemical analysis of mismatch repair proteins MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 and MSH6 for the assessment of microsatellite instability (MSI) status has been described in [26], analysis of beta-catenin overexpression in [27], of cyclin D1 in [23], and p21, p27 and p53 in [28].

Analysis of KRAS and BRAF mutation status

The PyroMark Q24 system (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) was used for pyrosequencing analysis of KRAS and BRAF mutations in DNA from 1 mm formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumour tissue cores taken from areas with >90% tumour cells. In brief, genomic DNA was extracted from tumour tissue using QIAamp MinElute spin columns (Qiagen) and DNA regions of interest were PCR-amplified (Veriti 96-Well Fast Thermal Cycler, Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA). KRAS codons 12 and 13 were analysed using Therascreen KRAS Pyro Kit (Qiagen). Analysis of BRAF mutation hotspots in codons 600 and 601 was performed using previously published PCR primers [29] and a novel BRAF sequencing primer (5′-TGATTTTGGTCTAGCTACA-3′) which was designed using the PyroMark Assay Design 2.0 software (Qiagen). All samples with a potential low-level mutation were reanalysed.

Statistical analysis

Associations between KRAS and BRAF mutation status and clinicopathological factors were explored by Pearson's Chi-square test. Kaplan-Meier analysis and log rank test were performed to illustrate the differences in cancer-specific survival (CSS). Cox proportional hazards regression was used for estimation of hazard ratio (HR) for death from CRC. A backward conditional method was used for variable selection in the multivariable model including age, gender, T stage, N stage, M stage, differentiation grade, vascular invasion, MSI status, and KRAS and BRAF mutation status. The interaction between investigative factors and sex was explored by a Cox model including the interaction variable. All survival analyses were repeated with overall mortality as endpoint and all tests were two-sided. A p value of 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0.

Results

Distribution of KRAS and BRAF mutations

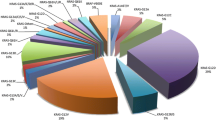

KRAS and BRAF mutations were successfully evaluated in 525 and 524 cases, respectively. The distribution of specific KRAS mutations is shown in Table 1. A total number of 334 (63.7%) tumours were KRAS wild-type and 191 (36.4%) were KRAS-mutated. Specifically, 156 (29.8%) cases harboured a KRAS codon 12 mutation, 34 (6.5%) a KRAS codon 13 mutation and 1 case (0.2%) had dual codons 12 and 13 mutations. The distribution of specific KRAS mutations did not differ between sexes (data not shown). KRAS and BRAF mutations were mutually exclusive. Further, 446 (85.1%) of the tumours were BRAF wild-type, 76 (14.5%) were BRAF V600E-mutated and 2 (0.4%) were BRAF K601E-mutated with a total of 78 (14.9%) cases harbouring a BRAF mutation.

Correlations of KRAS and BRAF mutations with clinicopathological and tumour biological parameters

As shown in Table 2, there was a significant association between KRAS wild-type tumours and MSI. Further, KRAS codon 13 mutation correlated with metastatic disease (M1) and p27 negativity. Notably, when KRAS codon 12-mutated tumours were compared with tumours being either KRAS wild-type or codon 13-mutated, there was a significantly higher proportion of mucinous tumours in the former category (p = 0.032 and p = 0.024).

BRAF mutation was significantly associated with older age, female sex, proximal tumour location, low differentiation grade, mucinous tumour type, MSI and expression of cyclin D1, and inversely associated with beta-catenin overexpression, p53 positivity and p27 expression.

Prognostic significance of KRAS and BRAF mutations

Hazard ratios for CSS according to KRAS and BRAF mutation status in the entire cohort, and strata according to sex, are shown in Table 3. In the entire cohort, a similar survival was seen for patients with KRAS wild-type and codon 12-mutated tumours, while patients with tumours harbouring a KRAS codon 13 mutation had a significantly reduced CSS (HR = 1.94; 95% CI = 1.18–3.19) in unadjusted, but not in adjusted analysis. KRAS codon 13, but not codon 12, mutation was also significantly associated with poor prognosis in women (HR = 2.58; 95% CI = 1.31–5.09) in unadjusted, but not in adjusted analysis. The KRAS mutation status was not prognostic in men.

There were no significant associations of BRAF mutation with CSS in the entire cohort or in women, neither in unadjusted nor in adjusted analysis. In men, BRAF mutation was not prognostic in unadjusted, but in adjusted analysis (HR = 3.50; 95% CI = 1.41–8.70). This finding led us to investigate whether the prognostic value of BRAF differs in different disease stages in men and women and found that BRAF status was particularly prognostic in lymph node-positive disease in men, but not in women (data not shown).

Specific point mutations in KRAS codon 12 or 13 had no significant impact on survival, neither in the entire cohort nor in strata according to gender (data not shown). Similar results were observed for the overall survival (data not shown). KRAS and BRAF mutation status did not predict response to standard adjuvant chemotherapy in curatively treated patients with stages III and IV disease (data not shown).

Prognostic value of BRAF mutation according to MSI status

As BRAF mutation has been previously reported to be associated with a particularly poor survival in cases with microsatellite stable (MSS) tumours [8, 15, 30, 31], we also examined whether the prognostic value of BRAF mutation differs by MSI status, overall and stratified for sex. As shown in Table 4, BRAF mutation was overall associated with a significantly shorter CSS in patients with MSS tumours in unadjusted analysis (HR = 2.36; 95% CI = 1.44–3.86) and borderline significant in adjusted analysis (HR = 1.80; 95% CI = 0.98–3.28). BRAF mutation was not prognostic in MSI tumours. Again, no prognostic significance was found for BRAF mutation in women, either in MSS or in MSI tumours. In men, BRAF mutation was an independent factor of poor prognosis in MSS tumours (unadjusted HR = 3.46, 95% CI = 1.78–6.74; adjusted HR = 4.91, 95% CI = 1.99–12.12). Adjusted analysis was not performed in MSI tumours due to the small subgroups.

Discussion

In this study, we have investigated the prognostic significance of KRAS codons 12 and 13, and BRAF mutations in incident colorectal cancer from a large prospective cohort study, with particular reference to sex-related differences. As regards to the KRAS mutation status, the results demonstrated a significant association of KRAS codon 13 mutation, but not codon 12, with poor prognosis, but this significance was not retained in adjusted analysis. These results support precious findings by Bazan et al. who reported KRAS codon 13 mutation to be an independent predictor of a poor prognosis [5]. Samowitz et al. have also described similar associations, but only borderline significant [13]. Other studies have further reported any KRAS mutation to be associated with poor outcome [6–8, 32]. In the present study, subgroup analysis revealed that KRAS codon 13 mutation was only prognostic in women and not in men, but only in unadjusted analysis. While no significant associations were found between KRAS mutations and sex, the significant association of KRAS mutation with MSS tumours found here is in concordance with the results from previous studies [6, 7, 9]. Further, the associations of KRAS codon 13 mutation with metastatic disease and codon 12 mutation with mucinous tumour type have also been demonstrated previously [5]. Taken together, these findings further indicate that specific KRAS codon mutations have different impact on protein functionality and should be taken into consideration when evaluating KRAS mutation status in the clinical setting. Furthermore, in light of the accentuated prognostic impact of KRAS codon 13 mutation in women, it will also be of interest to perform further studies on the associations of hormonal factors with KRAS mutation status in CRC.

In analysis of the entire cohort, BRAF mutation was not prognostic in women, but in men; BRAF mutation was significantly associated with an impaired survival in adjusted, but not in unadjusted analysis. This may be explained by the fact that the prognostic impact of BRAF mutation status was stronger in, e.g. lymph node-positive disease in men, but not in women. It is well established that BRAF mutation, in contrast to KRAS mutation, is associated with MSI [9, 10, 16, 33] and female sex [10, 33, 34], and our findings further validate this. In MSS tumours, BRAF mutation was significantly associated with a reduced CSS in unadjusted analysis, and was borderline significant in adjusted analysis. These findings are in concordance with several previous studies [9, 15, 17, 35], indicating that BRAF-mutated/MSS tumours represent a more aggressive tumour phenotype. However, the results from this study further demonstrate that BRAF-mutated/MSS tumours were not significantly associated with poor prognosis in women, but an independent predictor of a reduced CSS in men.

To date, no biomarkers have yet been incorporated into clinical protocols for prognostication and treatment stratification of CRC patients in the adjuvant setting, which still relies entirely on the assessment of conventional clinicopathological factors and patient performance. Approximately 20% of patients with stage II disease will develop recurrent disease and although several risk factors, e.g. <12 examined lymph nodes, T4 disease, vascular or neural invasion, low differentiation, acute operation and tumour perforation, have been suggested, the benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in this patient category is rather modest [36, 37]. Our results further indicate that this algorithm is not only in need of additional molecular biomarkers, but that sex should also be included as a variable.

The main purpose of this study was to analyse and compare the prognostic significance of KRAS and BRAF mutations in women and men, irrespective of adjuvant treatment. However, potential differences in response to standard adjuvant chemotherapy in curatively treated patients with stages III and IV disease according to KRAS and BRAF mutational status, MSI status and sex were also examined, whereby no significant differences were found. Therefore, the finding of BRAF mutation being a particularly negative prognostic factor in men warrants validation in additional independent patient cohorts, which may well be done in the retrospective setting, before further prospective study.

Although the proportion of patients in this study that may have received EGFR inhibitors upon recurrent disease is likely to be negligible, it is also important to consider potential sex differences when evaluating the results from trials related to response to EGFR inhibitors. For instance, results from several trials have demonstrated a significantly better response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in women with advanced non-small cell lung cancer compared to men [38, 39].

The higher prevalence of BRAF-mutated tumours in women, together with the lack of prognostic impact of BRAF mutations in female CRC, indicates the possibility of a link between hormonal factors and BRAF mutation status in CRC. Therefore, an influence of anthropometric and lifestyle factors is also plausible [22] and should be pursued in future studies.

As a cautionary remark, several of the here presented results, in particular related to gender, are derived from analyses of rather small subgroups and need validation in additional patient cohorts. The validity of the findings are however strengthened by the expected associations of KRAS and BRAF mutations with clinicopathological factors, e.g. KRAS and BRAF mutations being mutually exclusive [20], the significant associations between BRAF mutation, MSI [15, 20, 40] and mucinous phenotype [41, 42].

Apart from established clinicopathological parameters, we have also examined associations of KRAS and BRAF mutation status with several other investigative factors, i.e. beta-catenin overexpression and expression of p53, p21, p27 and cyclin D1. The observed inverse association between BRAF mutation and beta-catenin overexpression has been described earlier [43, 44] and is also in line with the previous findings of beta-catenin overexpression being associated with good prognosis in this cohort [28]. The observed associations between BRAF mutation and expression of p21 and cyclin D1, and loss of p27 and p53 expression have also been previously reported [45–48].

The Malmö Diet and Cancer Study is a population-based cohort study, wherein a potential selection bias compared with the general population must be taken into consideration. As previously denoted [23], the frequency of emergency surgery was only 8.3% which is lower than the commonly reported frequency of approximately 25% [49, 50], which may reflect a higher awareness of CRC among study participants. On the other hand, the distribution of clinical stages at diagnosis is in line with the expected [23, 25].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results from this large prospective cohort study provide further support to the accumulating evidence of BRAF-mutated microsatellite stable colorectal cancer having a particularly impaired prognosis. The finding of BRAF mutation being an independent factor of poor prognosis in male, but not in female colorectal cancer, both overall and in MSS tumours, is however novel and merits further study. Moreover, the findings in this study further emphasize the importance of taking sex into consideration in all cancer biomarker studies, since this may enable the development of more accurate prognostic nomograms for identification of patients with high-risk disease.

References

McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Abrams SL, Lee JT, Chang F, Bertrand FE, Navolanic PM, Terrian DM, Franklin RA, D'Assoro AB, Salisbury JL, Mazzarino MC, Stivala F, Libra M: Roles of the RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/AKT pathways in malignant transformation and drug resistance. Adv Enzyme Regul 2006, 46: 249–279. 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2006.01.004

Arrington AK, Heinrich EL, Lee W, Duldulao M, Patel S, Sanchez J, Garcia-Aguilar J, Kim J: Prognostic and predictive roles of KRAS mutation in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2012,13(10):12153–12168.

De Roock W, Piessevaux H, De Schutter J, Janssens M, De Hertogh G, Personeni N, Biesmans B, Van Laethem JL, Peeters M, Humblet Y, Van Cutsem E, Tejpar S: KRAS wild-type state predicts survival and is associated to early radiological response in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. Ann Oncol 2008,19(3):508–515.

Allegra CJ, Jessup JM, Somerfield MR, Hamilton SR, Hammond EH, Hayes DF, McAllister PK, Morton RF, Schilsky RL: American society of clinical oncology provisional clinical opinion: testing for KRAS gene mutations in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma to predict response to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody therapy. J Clin Oncol 2009,27(12):2091–2096. 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9170

Bazan V: Specific codon 13 K-ras mutations are predictive of clinical outcome in colorectal cancer patients, whereas codon 12 K-ras mutations are associated with mucinous histotype. Ann Oncol 2002,13(9):1438–1446. 10.1093/annonc/mdf226

Nash GM, Gimbel M, Cohen AM, Zeng ZS, Ndubuisi MI, Nathanson DR, Ott J, Barany F, Paty PB: KRAS mutation and microsatellite instability: two genetic markers of early tumor development that influence the prognosis of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2010,17(2):416–424. 10.1245/s10434-009-0713-0

Hutchins G, Southward K, Handley K, Magill L, Beaumont C, Stahlschmidt J, Richman S, Chambers P, Seymour M, Kerr D, Gray R, Quirke P: Value of mismatch repair, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in predicting recurrence and benefits from chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011,29(10):1261–1270. 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1366

Phipps AI, Buchanan DD, Makar KW, Win AK, Baron JA, Lindor NM, Potter JD, Newcomb PA: KRAS-mutation status in relation to colorectal cancer survival: the joint impact of correlated tumour markers. Br J Cancer 2013,108(8):1757–1764. 10.1038/bjc.2013.118

Ogino S, Nosho K, Kirkner GJ, Kawasaki T, Meyerhardt JA, Loda M, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS: CpG island methylator phenotype, microsatellite instability, BRAF mutation and clinical outcome in colon cancer. Gut 2009,58(1):90–96. 10.1136/gut.2008.155473

Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, Yan P, Fiocca R, Klingbiel D, Dietrich D, Biesmans B, Bodoky G, Barone C, Aranda E, Nordlinger B, Cisar L, Labianca R, Cunningham D, Van Cutsem E, Bosman F: Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60–00 trial. J Clin Oncol 2010,28(3):466–474. 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3452

Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, O'Callaghan CJ, Tu D, Tebbutt NC, Simes RJ, Chalchal H, Shapiro JD, Robitaille S, Price TJ, Shepherd L, Au HJ, Langer C, Moore MJ, Zalcberg JR: K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2008,359(17):1757–1765. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385

Zlobec I, Kovac M, Erzberger P, Molinari F, Bihl MP, Rufle A, Foerster A, Frattini M, Terracciano L, Heinimann K, Lugli A: Combined analysis of specific KRAS mutation, BRAF and microsatellite instability identifies prognostic subgroups of sporadic and hereditary colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 2010,127(11):2569–2575. 10.1002/ijc.25265

Samowitz WS, Curtin K, Schaffer D, Robertson M, Leppert M, Slattery ML: Relationship of Ki-ras mutations in colon cancers to tumor location, stage, and survival: a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2000,9(11):1193–1197.

Safaee Ardekani G, Jafarnejad SM, Tan L, Saeedi A, Li G: The prognostic value of BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer and melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012,7(10):e47054. 10.1371/journal.pone.0047054

Samowitz WS, Sweeney C, Herrick J, Albertsen H, Levin TR, Murtaugh MA, Wolff RK, Slattery ML: Poor survival associated with the BRAF V600E mutation in microsatellite-stable colon cancers. Cancer Res 2005,65(14):6063–6069. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0404

Farina-Sarasqueta A, van Lijnschoten G, Moerland E, Creemers GJ, Lemmens VE, Rutten HJ, van den Brule AJ: The BRAF V600E mutation is an independent prognostic factor for survival in stage II and stage III colon cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2010,21(12):2396–2402. 10.1093/annonc/mdq258

Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, Sartore-Bianchi A, Arena S, Saletti P, De Dosso S, Mazzucchelli L, Frattini M, Siena S, Bardelli A: Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008,26(35):5705–5712. 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0786

Souglakos J, Philips J, Wang R, Marwah S, Silver M, Tzardi M, Silver J, Ogino S, Hooshmand S, Kwak E, Freed E, Meyerhardt JA, Saridaki Z, Georgoulias V, Finkelstein D, Fuchs CS, Kulke MH, Shivdasani RA: Prognostic and predictive value of common mutations for treatment response and survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2009,101(3):465–472. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605164

De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D, De Schutter J, Biesmans B, Fountzilas G, Kalogeras KT, Kotoula V, Papamichael D, Laurent-Puig P, Penault-Llorca F, Rougier P, Vincenzi B, Santini D, Tonini G, Cappuzzo F, Frattini M, Molinari F, Saletti P, De Dosso S, Martini M, Bardelli A, Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Tabernero J, Macarulla T, Di Fiore F, Gangloff AO, Ciardiello F, Pfeiffer P, et al.: Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol 2010,11(8):753–762. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70130-3

Rajagopalan H, Bardelli A, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE: Tumorigenesis: RAF/RAS oncogenes and mismatch-repair status. Nature 2002,418(6901):934. 10.1038/418934a

Fridberg M, Jonsson L, Bergman J, Nodin B, Jirstrom K: Modifying effect of gender on the prognostic value of clinicopathological factors and Ki67 expression in melanoma: a population-based cohort study. Biol Sex Differ 2012,3(1):16. 10.1186/2042-6410-3-16

Brandstedt J, Wangefjord S, Nodin B, Gaber A, Manjer J, Jirstrom K: Gender, anthropometric factors and risk of colorectal cancer with particular reference to tumour location and TNM stage: a cohort study. Biol Sex Differ 2012,3(1):23. 10.1186/2042-6410-3-23

Wangefjord S, Manjer J, Gaber A, Nodin B, Eberhard J, Jirstrom K: Cyclin D1 expression in colorectal cancer is a favorable prognostic factor in men but not in women in a prospective, population-based cohort study. Biol Sex Differ 2011, 2: 10. 10.1186/2042-6410-2-10

Berglund G, Elmstahl S, Janzon L, Larsson SA: The malmo diet and cancer study. design and feasibility. J Intern Med 1993,233(1):45. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1993.tb00647.x

Larsson A, Johansson ME, Wangefjord S, Gaber A, Nodin B, Kucharzewska P, Welinder C, Belting M, Eberhard J, Johnsson A, Uhlén M, Jirström K: Overexpression of podocalyxin-like protein is an independent factor of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2011,105(5):666–672. 10.1038/bjc.2011.295

Eberhard J, Gaber A, Wangefjord S, Nodin B, Uhlen M, Ericson Lindquist K, Jirstrom K: A cohort study of the prognostic and treatment predictive value of SATB2 expression in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2012,106(5):931–938. 10.1038/bjc.2012.34

Nodin B, Johannesson H, Wangefjord S, O’Connor DP, Ericson-Lindquist K, Uhlen M, Jirstrom K, Eberhard J: Molecular correlates and prognostic significance of SATB1 expression in colorectal cancer. Diagn Pathol 2012,7(1):115. 10.1186/1746-1596-7-115

Wangefjord S, Brandstedt J, Ericson Lindquist K, Nodin B, Jirstrom K, Eberhard J: Associations of beta-catenin alterations and MSI screening status with expression of key cell cycle regulating proteins and survival from colorectal cancer. Diagn Pathol 2013,8(1):10. 10.1186/1746-1596-8-10

Richman SD, Seymour MT, Chambers P, Elliott F, Daly CL, Meade AM, Taylor G, Barrett JH, Quirke P: KRAS and BRAF mutations in advanced colorectal cancer are associated with poor prognosis but do not preclude benefit from oxaliplatin or irinotecan: results from the MRC FOCUS trial. J Clin Oncol 2009,27(35):5931–5937. 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4295

Kakar S, Deng G, Sahai V, Matsuzaki K, Tanaka H, Miura S, Kim YS: Clinicopathologic characteristics, CpG island methylator phenotype, and BRAF mutations in microsatellite-stable colorectal cancers without chromosomal instability. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008,132(6):958–964.

Ogino S, Shima K, Meyerhardt JA, McCleary NJ, Ng K, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Schaefer P, Whittom R, Hantel A, Benson AB 3rd, Spiegelman D, Goldberg RM, Bertagnolli MM, Fuchs CS: Predictive and prognostic roles of BRAF mutation in stage III colon cancer: results from intergroup trial CALGB 89803. Clin Cancer Res 2012,18(3):890–900. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2246

Nakanishi R, Harada J, Tuul M, Zhao Y, Ando K, Saeki H, Oki E, Ohga T, Kitao H, Kakeji Y, Maehara Y: Prognostic relevance of KRAS and BRAF mutations in Japanese patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2012. doi:10.1007/s10147–012–0501-x

Kalady MF, Dejulius KL, Sanchez JA, Jarrar A, Liu X, Manilich E, Skacel M, Church JM: BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer are associated with distinct clinical characteristics and worse prognosis. Dis Colon Rectum 2012,55(2):128–133. 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823c08b3

Capper D, Voigt A, Bozukova G, Ahadova A, Kickingereder P, von Deimling A, von Knebel DM, Kloor M: BRAF V600E-specific immunohistochemistry for the exclusion of Lynch syndrome in MSI-H colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 2013,133(7):1624–1630. 10.1002/ijc.28183

Bond CE, Umapathy A, Buttenshaw RL, Wockner L, Leggett BA, Whitehall VL: Chromosomal instability in BRAF mutant, microsatellite stable colorectal cancers. PLoS One 2012,7(10):e47483. 10.1371/journal.pone.0047483

Group QC: Adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with colorectal cancer: a randomised study. Lancet 2007,370(9604):2020–2029. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61866-2

Figueredo A, Coombes ME, Mukherjee S: Adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage II colon cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008., 3: CD005390

Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, Tamura T, Nakagawa K, Douillard JY, Nishiwaki Y, Vansteenkiste J, Kudoh S, Rischin D, Eek R, Horai T, Noda K, Takata I, Smit E, Averbuch S, Macleod A, Feyereislova A, Dong RP, Baselga J: Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) [corrected]. J Clin Oncol 2003,21(12):2237–2246. 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038

Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, Lynch TJ Jr, Prager D, Belani CP, Schiller JH, Kelly K, Spiridonidis H, Sandler A, Albain KS, Cella D, Wolf MK, Averbuch SD, Ochs JJ, Kay AC: Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 2003,290(16):2149–2158. 10.1001/jama.290.16.2149

Wang L, Cunningham JM, Winters JL, Guenther JC, French AJ, Boardman LA, Burgart LJ, McDonnell SK, Schaid DJ, Thibodeau SN: BRAF mutations in colon cancer are not likely attributable to defective DNA mismatch repair. Cancer Res 2003,63(17):5209–5212.

Ogino S, Brahmandam M, Cantor M, Namgyal C, Kawasaki T, Kirkner G, Meyerhardt JA, Loda M, Fuchs CS: Distinct molecular features of colorectal carcinoma with signet ring cell component and colorectal carcinoma with mucinous component. Mod Pathol 2006,19(1):59–68. 10.1038/modpathol.3800482

Li WQ, Kawakami K, Ruszkiewicz A, Bennett G, Moore J, Iacopetta B: BRAF mutations are associated with distinctive clinical, pathological and molecular features of colorectal cancer independently of microsatellite instability status. Mol Cancer 2006, 5: 2. 10.1186/1476-4598-5-2

Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, Meyerhardt JA, Shima K, Nosho K, Chan AT, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS, Ogino S: Association of CTNNB1 (beta-catenin) alterations, body mass index, and physical activity with survival in patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA 2011,305(16):1685–1694. 10.1001/jama.2011.513

Kawasaki T, Nosho K, Ohnishi M, Suemoto Y, Kirkner GJ, Dehari R, Meyerhardt JA, Fuchs CS, Ogino S: Correlation β-catenin localization with cyclooxygenase-2 expression and CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Neoplasia 2007,9(7):569–577. 10.1593/neo.07334

Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, Ogawa A, Dorfman I, Loda M, Fuchs CS: Down-regulation of p21 (CDKN1A/CIP1) is inversely associated with microsatellite instability and CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in colorectal cancer. J Pathol 2006,210(2):147–154. 10.1002/path.2030

Ogino S, Nosho K, Irahara N, Kure S, Shima K, Baba Y, Toyoda S, Chen L, Giovannucci EL, Meyerhardt JA, Fuchs CS: A cohort study of cyclin D1 expression and prognosis in 602 colon cancer cases. Clin Cancer Res 2009,15(13):4431–4438. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3330

Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, Yamaji T, Loda M, Fuchs CS: Loss of nuclear p27 (CDKN1B/KIP1) in colorectal cancer is correlated with microsatellite instability and CIMP. Mod Pathol 2007,20(1):15–22. 10.1038/modpathol.3800709

Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Liao X, Imamura Y, Yamauchi M, Qian ZR, Nishihara R, Sato K, Meyerhardt JA, Fuchs CS, Ogino S: Tumor TP53 expression status, body mass index and prognosis in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 2012,131(5):1169–1178. 10.1002/ijc.26495

Sjo OH, Larsen S, Lunde OC, Nesbakken A: Short term outcome after emergency and elective surgery for colon cancer. Colorectal Dis 2009,11(7):733–739. 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01613.x

Pavlidis TE, Marakis G, Ballas K, Rafailidis S, Psarras K, Pissas D, Sakantamis AK: Does emergency surgery affect resectability of colorectal cancer? Acta Chir Belg 2008,108(2):219–225.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society, The Gunnar Nilsson Cancer Foundation, Region Skåne and the Research Funds of Skåne University Hospital to KJ, and The Olle Engkvist Foundation, Anna Lisa and Sven-Eric Lundgren Foundation and Crafoord Foundation to JE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SW carried out the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. BN, NZ and MS carried out the pyrosequencing analyses and helped draft the manuscript. KEL carried out some of the immunohistochemical analyses. SW and JE collected the clinical data. JE and KJ conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wangefjord, S., Sundström, M., Zendehrokh, N. et al. Sex differences in the prognostic significance of KRAS codons 12 and 13, and BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer: a cohort study. Biol Sex Differ 4, 17 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2042-6410-4-17

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2042-6410-4-17