Abstract

Background

In patients with malaria mixed species infections are common and under reported. In PCR studies conducted in Asia mixed infection rates often exceed 20%. In South-East Asia, approximately one third of patients treated for falciparum malaria experience a subsequent Plasmodium vivax infection with a time interval suggesting relapse. It is uncertain whether the two infections are acquired simultaneously or separately. To determine whether mixed species infections in humans are derived from mainly from simultaneous or separate mosquito inoculations the literature on malaria species infection in wild captured anopheline mosquitoes was reviewed.

Methods

The biomedical literature was searched for studies of malaria infection and species identification in trapped wild mosquitoes and artificially infected mosquitoes. The study location and year, collection methods, mosquito species, number of specimens, parasite stage examined (oocysts or sporozoites), and the methods of parasite detection and speciation were tabulated. The entomological results in South East Asia were compared with mixed infection rates documented in patients in clinical studies.

Results

In total 63 studies were identified. Individual anopheline mosquitoes were examined for different malaria species in 28 of these. There were 14 studies from Africa; four with species evaluations in individual captured mosquitoes (SEICM). One study, from Ghana, identified a single mixed infection. No mixed infections were identified in Central and South America (seven studies, two SEICM). 42 studies were conducted in Asia and Oceania (11 from Thailand; 27 SEICM). The proportion of anophelines infected with Plasmodium falciparum parasites only was 0.51% (95% CI: 0.44 to 0.57%), for P. vivax only was 0.26% (95% CI: 0.21 to 0.30%), and for mixed P. falciparum and P. vivax infections was 0.036% (95% CI: 0.016 to 0.056%). The proportion of mixed infections in mosquitoes was significantly higher than expected by chance (P < 0.001), but was one fifth of that sufficient to explain the high rates of clinical mixed infections by simultaneous inoculation.

Conclusions

There are relatively few data on mixed infection rates in mosquitoes from Africa. Mixed species malaria infections may be acquired by simultaneous inoculation of sporozoites from multiply infected anopheline mosquitoes but this is relatively unusual. In South East Asia, where P. vivax infection follows P. falciparum malaria in one third of cases, the available entomological information suggests that the majority of these mixed species malaria infections are acquired from separate inoculations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Where transmission of both vivax and falciparum malaria is high in parts of Oceania, mixed species infections in humans are common. With frequent infection from repeated inoculation it is not surprising that infections accumulate and so comprise a multiplicity of genotypes and species. In South-East Asia where transmission of malaria is low, seasonal, and unstable people typically receive one infected mosquito bite each year or less, yet a remarkably high proportion (30 to 50%) of acute Plasmodium falciparum malaria infections are followed soon afterwards by an infection with Plasmodium vivax. Indeed in endemic areas in this region, the main clinical complication of falciparum malaria is subsequent vivax malaria, far outweighing the incidence of recrudescent falciparum malaria [1–5]. The intervals between presentation with falciparum malaria and the subsequent vivax episode are very similar to the intervals between acute vivax malaria and the first relapse [2, 5]. This suggests that the vivax malaria episode, which follows falciparum malaria, also results from a relapse. The very high rate of co-infection in South-East Asia has suggested that the two infections are acquired together despite the low transmission frequency.

Mixed species infections in patients are often under reported, with a tendency to over report the more dangerous P. falciparum. In endemic areas, where the prevalence of malaria revealed by sensitive PCR methods is much higher than evident from microscopy, high rates of mixed blood stage infection (~20%) have been reported, presumably because both infections are carried chronically [6, 7]. Lower rates of mixed species infection occur in symptomatic non-immunes presenting with acute falciparum malaria in low transmission settings. Even with sensitive PCR detection of low parasitaemia, the proportion of mixed infections detected does not approach the 30 to 50% required to explain the proportion of vivax malaria episodes, which follow P. falciparum malaria in these same patients. Simultaneous infection studies in the malaria therapy of neurosyphilis and in volunteers clearly showed that mixed infection could occur from simultaneous inoculation, that pre-erythrocytic development of P. falciparum was more rapid, and that in the blood stage infection P. falciparum tended to suppress P. vivax, so low level P. vivax parasitaemia might still be missed by current diagnostic methods [8–10]. Plasmodium vivax may also suppress P. falciparum; up to 10% of acute vivax malaria episodes in Thailand are followed shortly after by P. falciparum infections without reinfection [3, 11]. Blood stage infections in which both parasites are detectable could either derive from simultaneous inoculation of the sporozoites of the two species from a doubly infected anopheline mosquito, or a recently acquired infection of one species might supervene a chronic infection with the other. As transmission intensities in most of South East Asia are very low (EIRs typically < 1/year) the probabilities of separate inoculations within a narrow time window are extremely low [12]. To resolve these questions and understand better the epidemiology of mixed species infection in different transmission settings we examined the published literature on immunological and molecular parasite species identification in anopheline vectors in malaria endemic areas.

Methods

The NLM PubMed was searched since 1987 for publications in English describing studies on anopheline vectors in malaria endemic areas in which malaria parasite identification had been performed using immunological or molecular methods. The search terms were; anopheles AND sporozoite OR oocyst; Subheadings: Asia OR Africa OR America. Studies of both trapped wild mosquitoes and artificially infected mosquitoes were included. After compilation the lists were checked manually. The location of study and year, the collection method, mosquito species, number of specimens, parasite stage examined (oocysts or sporozoites), parasite detection method, and the results of the species identification were tabulated. Investigators in the South East Asian region were contacted for further information. ELISA and more recently PCR methods were used generally for species identification. The sensitivity of these different methods were also reviewed.

Results

In total, 42 studies were identified which were conducted in Asia and Oceania (11 were from Thailand) and 21 studies were conducted in other areas (14 were from Africa and 7 from Central or South America) between 1987 and 2011. Three of the American and three of the Asian studies involved blood feeding of anophelines and later dissection. In the remainder of the studies trapped wild anophelines were examined.

Sensitivity of different methods used for parasite identification

Table 1 shows the different methods used to identify mixed infections and, where quoted, their respective sensitivities and limits of detection.

Entomological studies from Asia and Oceania (Table 2, and 3)

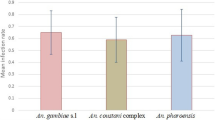

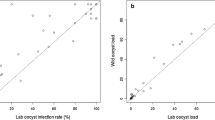

In four studies, sporozoites were examined but not speciated; 525 of 85,359 mosquitoes were positive. In ten studies some or all of the anophelines caught were pooled in groups before analysis. In these ten studies 155,497 anophelines were examined for P. falciparum and 184,744 were examined for P. vivax. Only one study reported mixed infections but, because of pooling, it cannot be ascertained whether this was in single mosquitoes. In 27 studies of trapped wild mosquitoes 167,465 individual anophelines were examined for P. falciparum sporozoites and in a further 2,049 the whole body was assessed. P. falciparum parasites only were identified in 1087 (0.51%; 95% CI: 0.44 to 0.57%). For P. vivax 334,698 anophelines were assessed and 544 were positive (0.25%%; 95% CI: 0.21 to 0.30%) for P. vivax alone. Mixed P. falciparum and P. vivax infections were assessed in 41,325 mosquitoes. If there was no association between the parasites then none of these would have been expected to have mixed species infection, whereas 17 (0.036%: 95% CI: 0.016 to 0.056%) had evidence of infection with both parasites (p < 0.001) (Figure 1). In studies conducted in Thailand, where most of the clinical trial information on mixed species infections has come from, 11,289 anophelines were examined in published studies and 23 P. falciparum (0.20%) and 24 P. vivax (0.21%) infections, but no mixed P. falciparum and P. vivax infections were found (Figure 1). Plasmodium malariae was found in 97 of 143,261 anophelines examined (0.051%), one of which was also infected with P. falciparum. Only one of the P. malariae was from mainland SE Asia. One mixed P. falciparum, P. vivax and Plasmodium knowlesi infection was identified in Vietnam. No Plasmodium ovale was identified. The VK210 and 247 P. vivax genotypes were distinguished in most studies; there were 207 VK210 and 279 VK247, and six were mixed genotype infections. None of the four artificial feeding studies in which different vectors were fed on parasitaemic blood yielded any mixed infections despite high rates of positivity for the individual parasite species.

Left side: Pie charts showing the proportion of individual anopheline vector mosquitoes examined which were positive for P. falciparum, P. vivax or both malaria parasite species in entomological studies conducted in Asia and Oceania (top) and in the subgroup of studies conducted in Thailand (bottom). On the right side are pie charts showing the proportion of malaria patients in Thailand with P. falciparum, P. vivax or both malaria parasite species concurrently assessed by PCR typing of blood samples (top). The proportion of patients in Thailand who have P. vivax infections following P. falciparum (without the possibility of reinfection) within a nine week period are shown below.

Comparison of mixed species infection rates in patients and in the mosquito vectors in Asia and Oceania

Studies conducted on the treatment of falciparum malaria during and immediately after the first world war indicated that vivax malaria commonly followed falciparum malaria acquired in Europe or Asia. In India rates ranged from seven to 40% [13]. Between March 1924 and July 1925 Sinton compared two different quinine regimens in the treatment of falciparum malaria in British soldiers [13]. They were followed for eight weeks at Kasauli (above the level of malaria transmission at an altitude of 6,000 feet in Himachal Pradesh). Of 76 soldiers completing follow-up 30 (39%) had subsequent vivax malaria. More recent information has come mainly from South-East Asia. In 1987, Looareesuwan et al[1] reported that of 320 adult patients treated in the Bangkok Hospital for Tropical Diseases and followed in hospital so that reinfection could be excluded definitely, 104 (32%) had a subsequent recurrence of vivax within two months. The relapse rate for vivax malaria in the same institution was 50% (200/400) [14].

Douglas et al[4] recently reviewed treatment responses in 10,549 patients (4,960 children aged < 15 years and 5,589 adults) treated for falciparum malaria in a malaria endemic area on the NorthWest border of Thailand. Reinfection could not be excluded. Of these patients, 9,385 (89.0%) had P. falciparum monoinfection and 1,164 (11.0%) had mixed P. falciparum/P. vivax infections according to microscopy at presentation. The cumulative proportion with P. vivax recurrence by day 63 was very similar to that documented in Bangkok; 31.5% (95% CI, 30.1% to 33.0%). However the overall rate of P. vivax infection following P. falciparum monoinfection may have been underestimated as the cumulative risk of vivax malaria was 51.1% (95% CI, 46.1% to 56.2%) after treatment with rapidly eliminated drugs (t1/2,1 day), 35.3% (95% CI, 31.8% to 39.0%) after treatment with intermediate half-life drugs (t1/2 1 to 7 days), and 19.6% (95% CI, 18.1% to 21.3%) after treatment with slowly eliminated drugs (t1/2 > 7 days). Some late relapses suppressed by the slowly eliminated drugs may therefore have emerged after day 63. The cumulative 63 day relapse/recurrence rate for vivax malaria at the same location was 63% (143/227)[15]. Two entomological evaluations were performed in this location. Of 596 anopheline vectors (Anopheles dirus, Anopheles minimus, Anopheles maculatus) examined individually five carried P. vivax and two carried P. falciparum. There were no mixed infections (McGready R: personal communication).

Smithuis et al[5] recently studied therapeutic responses to different ACT regimens in Myanmar in 808 adults and children with acute falciparum malaria or mixed species infections (16%). 330 (41%) patients had one or more episodes of P. vivax infection during follow-up. Of the 679 patients with P. falciparum infections only, 235 (35%) had subsequent P. vivax malaria. Children were nearly three times more likely to develop intercurrent vivax malaria than adults.

Taking the more conservative data from Bangkok in Thailand where reinfection could be excluded, then if all vivax infections are acquired from simultaneous inoculation it would be expected that the mixed falciparum and vivax infection proportion in mosquitoes would be 32% of all the P. falciparum infected mosquitoes

In fact no mixed species infections were recorded in Thailand among 23 P. falciparum positive mosquitoes (Figure 1), whereas seven or eight would have been expected if all mixed species infections had been acquired by simultaneous inoculation (p = 0.01). Overall in Asia and Oceania only 6.6% of the P. falciparum infected mosquitoes also carried P. vivax, a proportion that is considerably lower than expected from the clinical data.

Entomological studies from Central and South America (Table 4)

In five of the seven studies identified some or all the mosquitoes were pooled before analysis and in three studies anopheline mosquitoes were infected artificially. One of these studies examined only for P. vivax. None of these studies detected mixed infections despite estimated infection rates in the pooled mosquitoes ranging from 0.1 to 3.2% for P. vivax and 0 to 0.87% for P. falciparum. In the two studies in which individual anophelines were examined (one from Columbia, the other from Brazil) 7,125 individual anophelines were examined. P. falciparum sporozoites only were identified in 3 (0.042%), P. malariae in 1 (0.014%), and 50 were positive (0.70%) for P. vivax alone (47 Pv VK 210 and 3 Pv VK 247). No mixed P. falciparum and P. vivax infections were identified.

Entomological studies from Africa (Table 4)

In one of the 14 studies identified mosquitoes were artificially infected and in two studies mosquitoes were pooled before analysis. Eight studies examined the mosquitoes only for P. falciparum. In the artificial feeding study conducted in Guinea-Bissau where all species were investigated 510 anophelines were examined and infection rates with single species ranged from 5 to 15% for P. falciparum, 1 to 2% for P. malariae and 0.54 to 5% for P. ovale. Mixed infection rates ranged from 0.4 to 15%. In the 11 studies in which individual anophelines were examined 1654 of 27738 (6%) had P. falciparum sporozoites although rates for individual vectors in different studies varied between 0.7% and 78%. In the four studies where mixed infections were studied specifically, two studies examined only for P. vivax. In the remaining two studies one from Cameroon did not identify mixed infections. In the other study from Ghana overall infectivity rate was 7.7% for Anopheles gambiae (s.s) and 4.9% for Anopheles funestus. Of the sporozoite positive mosquitoes 5.7% contained P. malariae only and 5.7% contained P. ovale only and a single A. gambiae (s.s) was identified carrying mixed P. falciparum and P. malariae. The remainder were positive for P. falciparum only. No mixed P. falciparum and P. vivax infections were identified. P. vivax was reported only from Ethiopia where 14 (1.8%) of 796 mosquitoes were positive for P. vivax and 4 (0.5%) were positive for P. falciparum. No mixed infections were identified in this study.

Discussion

In areas where malaria transmission is stable and intense the majority of the human population is constantly infected, although older children and adults often have parasite densities below the level of microscopy detection. Many parts of Africa have this pattern of malaria transmission. Mixed genotype P. falciparum infections are common, but there are relatively few studies which have examined the prevalence of other infections. In Asia and Oceania, these areas of intense transmission tend to be very small focal forest or forest fringe areas, and much of the coastal part of the Island of New Guinea. In those areas where both P. falciparum and P. vivax are prevalent mixed species infections with both species are common but maybe also be below the level of microscopy detection [8]. Both infections coexist chronically [16]. Sensitive PCR methods reveal high rates of mixed species infection (~20%) [6] although it seems likely that the majority of mixed infections in humans are acquired from separate mosquito inoculations. Asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic individuals who are parasitaemic have declared themselves able to control the infections and so are much more likely to have a multiplicity of different genotypes present (albeit at low densities) and also mixed species infections.

In contrast in much of the remainder of Asia transmission is generally low and seasonal and, although P. vivax infections may still be asymptomatic, P. falciparum malaria is usually accompanied by illness and treatment seeking. Symptomatic infections are seen at all ages, although the burden of symptomatic vivax malaria is in young children. In this epidemiological context mixed species infections are found in 10% or less of acute infections, yet approximately one third of patients still experience vivax malaria following falciparum malaria. The high efficacy of initial falciparum malaria treatment against P. vivax and the time interval between initial presentation and the subsequent vivax malaria episode suggests that it is a relapse. This presumed relapse was thought to result from simultaneously acquired mixed species infection, but the evidence reviewed here does not support this hypothesis. The proportion of P. falciparum infected mosquitoes overall which also carried P. vivax in Asia and Oceania was only 6.6% overall. As expected most mixed infections in mosquitoes were found in studies on the island of New Guinea where transmission of both species is intense. None were found in Thailand where one third of P. falciparum malaria is followed by P. vivax. Thus, the proportion of mixed infections in anopheline mosquito vectors in Asia and Oceania is approximately one fifth of that expected. These findings suggest that simultaneous inoculation of the two malaria species does occur, and indeed is more frequent than would be expected by chance alone, but that the majority of mixed species infections do not derive from a single mosquito bite.

Several explanations are possible. The entomology sampling frameworks in these studies may not have been representative. The vectors might not have been adequately representative of those transmitting malaria. The laboratory methods may have been insensitive (Table 1) or not designed specifically to identify mixed species infections. These concerns were addressed to some extent in those studies in which some mixed infections were identified. Lack of sensitivity seems an unlikely explanation for the observations. As only a small fraction of the salivary gland sporozoites are inoculated by a biting anopheline mosquito- it seems unlikely that these would derive from very small subpopulations of different species sporozoites which were below the level of antigen or PCR detection.

If the mixed species infections are all acquired from simultaneous inoculation it would also requires very high rates of concomitant P. falciparum and P. vivax gametocyte carriage at infectious densities in the blood of the parasitaemic population. This may well occur in high transmission settings but is rare in low unstable transmission settings and is not supported by the mosquito feeding studies reported here. As P. vivax develops more rapidly than P. falciparum in the anopheline vector, it also demands mosquito longevity. If the two infections were acquired separately then the close and reproducible temporal association between the infections needs explanation. Although the distribution of infected mosquito biting undoubtedly clusters it would require a remarkable degree of association for one third of all P. falciparum inoculations to be accompanied within a day or two by a P. vivax inoculation -when average inoculation rates are less than one infected bite per person per year! Nevertheless mixed species infections in anopheline mosquitoes do occur in Asia significantly more frequently than expected by chance so it is clear that simultaneous transmission does occur and does contribute to mixed infections. It is likely to account for the significant proportion of acute symptomatic malaria in low transmission settings where both species are identified in the blood at presentation.

The data from Central and South America where transmission is generally low and unstable also showed low rates of mosquito infection. No mixed infections were found but as P. falciparum and P. malariae infection rates were also very low this negative finding has limited significance. There are surprisingly few data from Africa on species other than P. falciparum. Plasmodium vivax was identified in Ethiopia as expected. In Ghana where transmission is intense mixed infection was identified. Artificial infection studies in Guinea-Bissau suggested that mixed infection of mosquitoes would be frequent, but these data are too few to draw firm conclusions on the entomology of mixed malaria infection in Africa.

This review is almost certainly an underestimate of the available information. For example, much of the Central and South American literature is in Spanish or Portuguese and some of the African literature is in French. The search strategy employed may well have missed studies in English, which lacked the key words. Nevertheless because of the large apparent discrepancies between mixed species infection rates in the anopheline mosquito vectors and humans this comprehensive sample of the literature provides a convincing message. Mixed infections of anopheline vectors do occur and account for some of the mixed infections in humans. However in South East Asia where P. vivax infections follows P. falciparum malaria in one third of cases, the published data suggests that the majority of these mixed infections are not acquired by simultaneous inoculation. A more plausible explanation is that P. vivax relapse is stimulated by symptomatic falciparum malaria infection.

References

Looareesuwan S, White NJ, Chittamas S, Bunnag D, Harinasuta T: High rate of Plasmodium vivax relapse following treatment of falciparum malaria in Thailand. Lancet. 1987, 2: 1052-1055.

Imwong M, Snounou G, Pukrittayakamee S, Tanomsing N, Kim JR, Nandy A, Guthmann JP, Nosten F, Carlton J, Looareesuwan S, Nair S, Sudimack D, Day NP, Anderson TJ, White NJ: Relapses of Plasmodium vivax infection usually result from activation of heterologous hypnozoites. J Infect Dis. 2007, 195: 927-933. 10.1086/512241.

Mayxay M, Pukritrayakamee S, Chotivanich K, Imwong M, Looareesuwan S, White NJ: Identification of cryptic coinfection with Plasmodium falciparum in patients presenting with vivax malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001, 65: 588-592.

Douglas NM, Nosten F, Ashley EA, Phaiphun L, van Vugt M, Singhasivanon P, White NJ, Price RN: Plasmodium vivax recurrence following falciparum and mixed species malaria: risk factors and effect of antimalarial kinetics. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 52: 612-620. 10.1093/cid/ciq249.

Smithuis F, Kyaw MK, Phe O, Win T, Aung PP, Oo AP, Naing AL, Nyo MY, Myint NZ, Imwong M, Ashley E, Lee SJ, White NJ: Effectiveness of five artemisinin combination regimens with or without primaquine in uncomplicated falciparum malaria: an open-label randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010, 10: 673-681. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70187-0.

Gupta B, Gupta P, Sharma A, Singh V, Dash AP, Das A: High proportion of mixed-species Plasmodium infections in India revealed by PCR diagnostic assay. Trop Med Int Health. 2010, 15: 819-824. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02549.x.

Zakeri S, Kakar Q, Ghasemi F, Raeisi A, Butt W, Safi N, Afsharpad M, Memon MS, Gholizadeh S, Salehi M, Atta H, Zamani G, Djadid ND: Detection of mixed Plasmodium falciparum &P. vivax infections by nested-PCR in Pakistan, Iran & Afghanistan. Indian J Med Res. 2010, 132: 31-35.

Mayxay M, Pukrittayakamee S, Newton PN, White NJ: Mixed-species malaria infections in humans. Trends Parasitol. 2004, 20: 233-240. 10.1016/j.pt.2004.03.006.

Putaporntip C, Hongsrimuang T, Seethamchai S, Kobasa T, Limkittikul K, Cui L, Jongwutiwes S: Differential prevalence of Plasmodium infections and cryptic Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in humans in Thailand. J Infect Dis. 2009, 199: 1143-1150. 10.1086/597414.

Steenkeste N, Rogers WO, Okell L, Jeanne I, Incardona S, Duval L, Chy S, Hewitt S, Chou M, Socheat D, Babin FX, Ariey F, Rogier C: Sub-microscopic malaria cases and mixed malaria infection in a remote area of high malaria endemicity in Rattanakiri province, Cambodia: implication for malaria elimination. Malar J. 2010, 9: 108-10.1186/1475-2875-9-108.

Mason DP, Krudsood S, Wilairatana P, Viriyavejakul P, Silachamroon U, Chokejindachai W, Singhasivanon P, Supavej S, McKenzie FE, Looareesuwan S: Can treatment of P. vivax lead to a unexpected appearance of falciparum malaria?. SE Asian J Trop Med Publ Hlth. 2001, 32: 57-63.

Gingrich JB, Weatherhead A, Sattabongkot J, Pilakasiri C, Wirtz RA: Hyperendemic malaria in a Thai village: dependence of year-round transmission on focal and seasonally circumscribed mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) habitats. J Med Entomol . 1990, 27: 1016-1026.

Sinton J: Studies in malaria, with special reference to treatment. Part II. The effects of treatment on the prevention of relapse in infections with Plasmodium falciparum. Indian J Med Res. 1962, 13: 579-601.

Silachamroon U, Krudsood S, Treeprasertsuk S, Wilairatana P, Chalearmrult K, Mint HY, Maneekan P, White NJ, Gourdeuk VR, Brittenham GM, Looareesuwan S: Clinical trial of oral artesunate with or without high-dose primaquine for the treatment of vivax malaria in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003, 69: 14-18.

Luxemburger C, van Vugt M, Jonathan S, McGready R, Looareesuwan S, White NJ, Nosten F: Treatment of vivax malaria on the western border of Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999, 93: 433-438. 10.1016/S0035-9203(99)90149-9.

Bruce MC, Galinski MR, Barnwell JW, Donnelly CA, Walmsley M, Alpers MP, Walliker D, Day KP: Genetic diversity and dynamics of Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax populations in multiply infected children with asymptomatic malaria infections in Papua New Guinea. Parasitology. 2000, 121 (Pt 3): 257-272.

Wirtz RA, Burkot TR, Andre RG, Rosenberg R, Collins WE, Roberts DR: Identification of Plasmodium vivax sporozoites in mosquitoes using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985, 34: 1048-1054.

Wirtz RA, Ballou WR, Schneider I, Chedid L, Gross MJ, Young JF, Hollingdale M, Diggs CL, Hockmeyer WT: Plasmodium falciparum: immunogenicity of circumsporozoite protein constructs produced in Escherichia coli. Exp Parasitol. 1987, 63: 166-172. 10.1016/0014-4894(87)90158-5.

Collins FH, Procell PM, Campbell GH, Collins WE: Monoclonal antibody-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for detection of Plasmodium malariae sporozoites in mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988, 38: 283-288.

Harada M, Ishikawa H, Matsuoka H, Ishii A, Suguri S: Estimation of the sporozoite rate of malaria vectors using the polymerase chain reaction and a mathematical model. Acta Med Okayama. 2000, 54: 165-171.

Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, Thaithong S, Brown KN: High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993, 61: 315-320. 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90077-B.

Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Jarra W, Thaithong S, Brown KN: Identification of the four human malaria parasite species in field samples by the polymerase chain reaction and detection of a high prevalence of mixed infections. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993, 58: 283-292. 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90050-8.

Lardeux F, Tejerina R, Aliaga C, Ursic-Bedoya R, Lowenberger C, Chavez T: Optimization of a semi-nested multiplex PCR to identify Plasmodium parasites in wild-caught Anopheles in Bolivia, and its application to field epidemiological studies. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008, 102: 485-492. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.02.006.

Rubio JM, Benito A, Roche J, Berzosa PJ, Garcia ML, Mico M, Edu M, Alvar J: Semi-nested, multiplex polymerase chain reaction for detection of human malaria parasites and evidence of Plasmodium vivax infection in Equatorial Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999, 60: 183-187.

Rubio JM, Post RJ, van Leeuwen WM, Henry MC, Lindergard G, Hommel M: Alternative polymerase chain reaction method to identify Plasmodium species in human blood samples: the semi-nested multiplex malaria PCR (SnM-PCR). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002, 96 (Suppl 1): S199-204.

Hasan AU, Suguri S, Sattabongkot J, Fujimoto C, Amakawa M, Harada M, Ohmae H: Implementation of a novel PCR based method for detecting malaria parasites from naturally infected mosquitoes in Papua New Guinea. Malar J. 2009, 8: 182-10.1186/1475-2875-8-182.

Mangold KA, Manson RU, Koay ES, Stephens L, Regner M, Thomson RB, Peterson LR, Kaul KL: Real-time PCR for detection and identification of Plasmodium spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43: 2435-2440. 10.1128/JCM.43.5.2435-2440.2005.

Nakazawa S, Marchand RP, Quang NT, Culleton R, Manh ND, Maeno Y: Anopheles dirus co-infection with human and monkey malaria parasites in Vietnam. Int J Parasitol. 2009, 39: 1533-1537. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.08.005.

Perandin F, Manca N, Calderaro A, Piccolo G, Galati L, Ricci L, Medici MC, Arcangeletti MC, Snounou G, Dettori G, Chezzi C: Development of a real-time PCR assay for detection of Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, and Plasmodium ovale for routine clinical diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42: 1214-1219. 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1214-1219.2004.

Bangs MJ, Rusmiarto S, Gionar YR, Chan AS, Dave K, Ryan JR: Evaluation of a dipstick malaria sporozoite panel assay for detection of naturally infected mosquitoes. J Med Entomol. 2002, 39: 324-330. 10.1603/0022-2585-39.2.324.

Ryan JR, Dave K, Collins KM, Hochberg L, Sattabongkot J, Coleman RE, Dunton RF, Bangs MJ, Mbogo CM, Cooper RD, Schoeler GB, Rubio-Palis Y, Magris M, Romer LI, Padilla N, Quakyi IA, Bigoga J, Leke RG, Akinpelu O, Evans B, Walsey M, Patterson P, Wirtz RA, Chan AS: Extensive multiple test centre evaluation of the VecTest malaria antigen panel assay. Med Vet Entomol. 2002, 16: 321-327. 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2002.00368.x.

Lulu M, Hermans PW, Gemetchu T, Petros B, Miorner H: Detection of Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites in naturally infected anopheline species using a fluorescein-labelled DNA probe. Acta Trop. 1997, 63: 33-42. 10.1016/S0001-706X(96)00615-8.

Kimura M, Kaneko O, Liu Q, Zhou M, Kawamoto F, Wataya Y, Otani S, Yamaguchi Y, Tanabe K: Identification of the four species of human malaria parasites by nested PCR that targets variant sequences in the small subunit rRNA gene. Parasitol Int. 1997, 46: 91-95. 10.1016/S1383-5769(97)00013-5.

Tangin A, Komichi Y, Wagatsuma Y, Rashidul H, Wataya Y, Kim HS: Detection of malaria parasites in mosquitoes from the malaria-endemic area of Chakaria, Bangladesh. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008, 31: 703-708. 10.1248/bpb.31.703.

Upatham ES, Prasittisuk C, Ratanatham S, Green CA, Rojanasunan W, Setakana P, Theerasilp N, Tremongkol A, Viyanant V, Pantuwatana S: Bionomics of Anopheles maculatus complex and their role in malaria transmission in Thailand. SE Asian J Trop Med Publ Hlth. 1988, 19: 259-269.

Coleman RE, Kiattibut C, Sattabongkot J, Ryan J, Burkett DA, Kim HC, Lee WJ, Klein TA: Evaluation of anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from the republic of Korea for Plasmodium vivax circumsporozoite protein. J Med Entomol. 2002, 39: 244-247. 10.1603/0022-2585-39.1.244.

Bangs MJ, Rusmiarto S, Anthony RL, Wirtz RA, Subianto DB: Malaria transmission by Anopheles punctulatus in the highlands of Irian Jaya, Indonesia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1996, 90: 29-38.

Frances SP, Klein TA, Wirtz RA, Eamsila C, Pilakasiri C, Linthicum KJ: Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax circumsporozoite proteins in anophelines (Diptera: Culicidae) collected in eastern Thailand. J Med Entomol . 1996, 33: 990-991.

Mya MM, Saxena RK, Soe P: Study of malaria in a village of lower Myanmar. Ind J Malariol. 2002, 39: 96-102.

Harbach RE, Gingrich JB, Pang LW: Some entomological observations on malaria transmission in a remote village in northwestern Thailand. J Am Mosquito Control Ass. 1987, 3: 296-301.

Toma T, Miyagi I, Okazawa T, Kobayashi J, Saita S, Tuzuki A, Keomanila H, Nambanya S, Phompida S, Uza M, Takakura M: Entomological surveys of malaria in Khammouane Province, Lao PDR, in 1999 and 2000. SE Asian J Trop Med Publ Hlth. 2002, 33: 532-546.

Oh SS, Hur MJ, Joo GS, Kim ST, Go JM, Kim YH, Lee WG, Shin EH: Malaria vector surveillance in Ganghwa-do, a malaria-endemic area in the Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2010, 48: 35-41. 10.3347/kjp.2010.48.1.35.

Dev V, Sangma BM, Dash AP: Persistent transmission of malaria in Garo hills of Meghalaya bordering Bangladesh, north-east India. Malar J. 2010, 9: 263-10.1186/1475-2875-9-263.

Sahu SS, Vijayakumar T, Kalyanasundaram M, Subramanian S, Jambulingam P: Impact of lambdacyhalothrin capsule suspension treated bed nets on malaria in tribal villages of Malkangiri district, Orissa, India. Indian J Med Res. 2008, 128: 262-270.

Lee HW, Shin EH, Cho SH, Lee HI, Kim CL, Lee WG, Moon SU, Lee JS, Lee WJ, Kim TS: Detection of vivax malaria sporozoites naturally infected in Anopheline mosquitoes from endemic areas of northern parts of Gyeonggi-do (Province) in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2002, 40: 75-81. 10.3347/kjp.2002.40.2.75.

Mahapatra N, Marai NS, Ranjit MR, Parida SK, Hansdah DP, Hazra RK, Kar SK: Detection of Plasmodium falciparum infection in anopheles mosquitoes from Keonjhar district, Orissa, India. J Vector Borne Dis. 2006, 43: 191-194.

Cooper RD, Waterson DG, Frances SP, Beebe NW, Pluess B, Sweeney AW: Malaria vectors of Papua New Guinea. Int J Parasitol. 2009, 39: 1495-1501. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.05.009.

Van Bortel W, Trung HD, Hoi le X, Van Ham N, Van Chut N, Luu ND, Roelants P, Denis L, Speybroeck N, D'Alessandro U, Coosemans M: Malaria transmission and vector behaviour in a forested malaria focus in central Vietnam and the implications for vector control. Malar J. 2010, 9: 373-10.1186/1475-2875-9-373.

Mohanty A, Swain S, Singh DV, Mahapatra N, Kar SK, Hazra RK: A unique methodology for detecting the spread of chloroquine-resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum, in previously unreported areas, by analyzing anophelines of malaria endemic zones of Orissa, India. Infection, genetics and evolution: journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 2009, 9: 462-467.

Burkot TR, Dye C, Graves PM: An analysis of some factors determining the sporozoite rates, human blood indexes, and biting rates of members of the Anopheles punctulatus complex in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989, 40: 229-234.

Burkot TR, Wirtz RA, Paru R, Garner P, Alpers MP: The population dynamics in mosquitoes and humans of two Plasmodium vivax polymorphs distinguished by different circumsporozoite protein repeat regions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992, 47: 778-786.

Bockarie MJ, Alexander N, Bockarie F, Ibam E, Barnish G, Alpers M: The late biting habit of parous Anopheles mosquitoes and pre-bedtime exposure of humans to infective female mosquitoes. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996, 90: 23-25. 10.1016/S0035-9203(96)90465-4.

Hii JL, Smith T, Mai A, Ibam E, Alpers MP: Comparison between anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) caught using different methods in a malaria endemic area of Papua New Guinea. Bull Entomol Res. 2000, 90: 211-219.

Wirtz RA, Burkot TR, Graves PM, Andre RG: Field evaluation of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax sporozoites in mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from Papua New Guinea. J Med Entomol. 1987, 24: 433-437.

Alam MS, Khan MG, Chaudhury N, Deloer S, Nazib F, Bangali AM, Haque R: Prevalence of anopheline species and their Plasmodium infection status in epidemic-prone border areas of Bangladesh. Malar J. 2010, 9: 15-10.1186/1475-2875-9-15.

Trung HD, Van Bortel W, Sochantha T, Keokenchanh K, Quang NT, Cong LD, Coosemans M: Malaria transmission and major malaria vectors in different geographical areas of Southeast Asia. Trop Med Int Health. 2004, 9: 230-237. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01179.x.

Swain S, Mohanty A, Mahapatra N, Parida SK, Marai NS, Tripathy HK, Kar SK, Hazra RK: The development and evaluation of a single step multiplex PCR for simultaneous detection of Anopheles annularis group mosquitoes, human host preference and Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite presence. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 103: 1146-1152. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.03.022.

Appawu MA, Bosompem KM, Dadzie S, McKakpo US, Anim-Baidoo I, Dykstra E, Szumlas DE, Rogers WO, Koram K, Fryauff DJ: Detection of malaria sporozoites by standard ELISA and VecTestTM dipstick assay in field-collected anopheline mosquitoes from a malaria endemic site in Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. 2003, 8: 1012-1017. 10.1046/j.1360-2276.2003.00127.x.

Moreno M, Cano J, Nzambo S, Bobuakasi L, Buatiche JN, Ondo M, Micha F, Benito A: Malaria Panel Assay versus PCR: detection of naturally infected Anopheles melas in a coastal village of Equatorial Guinea. Malar J. 2004, 3: 20-10.1186/1475-2875-3-20.

Bigoga JD, Manga L, Titanji VP, Coetzee M, Leke RG: Malaria vectors and transmission dynamics in coastal south-western Cameroon. Malar J. 2007, 6: 5-10.1186/1475-2875-6-5.

Oyewole IO, Awolola TS: Impact of urbanisation on bionomics and distribution of malaria vectors in Lagos, southwestern Nigeria. J Vector Borne Dis. 2006, 43: 173-178.

Cuamba N, Choi KS, Townson H: Malaria vectors in Angola: distribution of species and molecular forms of the Anopheles gambiae complex, their pyrethroid insecticide knockdown resistance (kdr) status and Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite rates. Malar J. 2006, 5: 2-10.1186/1475-2875-5-2.

Quiñones ML RF, Calle DA, Harbach RE, Erazo HF, Linton YM: Incrimination of Anopheles (Nyssorhynchus) rangeli and An. (Nys.) oswaldoi as natural vectors of Plasmodium vivax in Southern Colombia. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2006, 101: 617-623. 10.1590/S0074-02762006000600007.

Santos RL, Padilha A, Costa MD, Costa EM, Dantas-Filho Hde C, Povoa MM: Malaria vectors in two indigenous reserves of the Brazilian Amazon. Rev Saude Publica. 2009, 43: 859-868. 10.1590/S0034-89102009000500016.

Kasili S, Odemba N, Ngere FG, Kamanza JB, Muema AM, Kutima HL: Entomological assessment of the potential for malaria transmission in Kibera slum of Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of vector borne diseases. 2009, 46: 273-279.

Taye A, Hadis M, Adugna N, Tilahun D, Wirtz RA: Biting behavior and Plasmodium infection rates of Anopheles arabiensis from Sille, Ethiopia. Acta Trop. 2006, 97: 50-54. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.08.002.

Annan Z, Durand P, Ayala FJ, Arnathau C, Awono-Ambene P, Simard F, Razakandrainibe FG, Koella JC, Fontenille D, Renaud F: Population genetic structure of Plasmodium falciparum in the two main African vectors, Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007, 104: 7987-7992. 10.1073/pnas.0702715104.

Abonuusum A, Owusu-Daako K, Tannich E, May J, Garms R, Kruppa T: Malaria transmission in two rural communities in the forest zone of Ghana. Parasitol Res. 2011, 108: 1465-1471. 10.1007/s00436-010-2195-1.

Tanga MC, Ngundu WI, Tchouassi PD: Daily survival and human blood index of major malaria vectors associated with oil palm cultivation in Cameroon and their role in malaria transmission. Trop Med Int Health. 2011, 16: 447-457. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02726.x.

Shililu JI, Maier WA, Seitz HM, Orago AS: Seasonal density, sporozoite rates and entomological inoculation rates of Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus in a high-altitude sugarcane growing zone in Western Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 1998, 3: 706-710. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00282.x.

Acknowledgements and Funding

This study was part of the Wellcome Trust Mahidol University-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Programme funded by the Wellcome Trust of Great Britain. MI is supported by the Office of the Higher Education Commission and Mahidol University under the National Research Universities Initiative and a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Fellow (grant 080867/Z/06/Z).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

NJW, MI and NJPD conceived of this review. MI and SN carried out the review. NJW and NJPD conducted the analysis. MI, SN, NJPD and NJW participated in the interpretation and presentation. MI and NJW drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Imwong, M., Nakeesathit, S., Day, N.P. et al. A review of mixed malaria species infections in anopheline mosquitoes. Malar J 10, 253 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-10-253

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-10-253