Abstract

Background

The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS), which assesses level of sedation and agitation, is a simple observational instrument which was developed and validated for the intensive care setting. Although used and recommended in palliative care settings, further validation is required in this patient population. The aim of this study was to explore the validity and feasibility of a version of the RASS modified for palliative care populations (RASS-PAL).

Methods

A prospective study, using a mixed methods approach, was conducted. Thirteen health care professionals (physicians and nurses) working in an acute palliative care unit assessed ten consecutive patients with an agitated delirium or receiving palliative sedation. Patients were assessed at five designated time points using the RASS-PAL. Health care professionals completed a short survey and data from semi-structured interviews was analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results

The inter-rater intraclass correlation coefficient range of the RASS-PAL was 0.84 to 0.98 for the five time points. Professionals agreed that the tool was useful for assessing sedation and was easy to use. Its role in monitoring delirium however was deemed problematic. Professionals felt that it may assist interprofessional communication. The need for formal education on why and how to use the instrument was highlighted.

Conclusion

This study provides preliminary validity evidence for the use of the RASS-PAL by physicians and nurses working in a palliative care unit, specifically for assessing sedation and agitation levels in the management of palliative sedation. Further validity evidence should be sought, particularly in the context of assessing delirium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Best practices in palliative sedation (PS) include the use of standardized instruments to assess the level of sedation and enhance monitoring and documentation [1–4]. The European Association for Palliative Care’s (EAPC) Expert Working Group on Palliative Sedation recommends the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) or similar tools to assess sedation and distress levels in palliative care patients with lowered consciousness [1].

The original RASS, developed for adult intensive care unit (ICU) patients, demonstrates strong inter-rater reliability in that setting [5–7]. It is a simple observational instrument assessing levels of sedation and agitation that requires no patient input [8] with scores ranging from +4 (representing an overtly combative patient) to -5, representing a patient who cannot be aroused by either voice or physical stimulation. A recent study found the RASS to be considerably less time consuming and easier to use than two other similar instruments [8]. A modified version of the RASS administered daily reported good sensitivity and specificity for incident delirium in veterans [9]. Although the RASS is currently used in many palliative care settings [8, 10–12], there has only been one recently published report exploring its reliability in Spanish patients with advanced cancer [13]. Refractory agitated delirium at the end of life is the most frequent indication for palliative sedation [2, 10, 14]. The goal of this study was to investigate the validity and feasibility of the RASS-PAL, a version of the RASS slightly modified for palliative care populations, in patients experiencing agitated delirium or receiving PS.

Methods

A prospective exploratory study, using a mixed methods approach, was undertaken. The study was approved by the institutions’ Research Ethics Boards (Bruyère Continuing Care Research Ethics Board and Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board). Informed consent from patients was waivered. Participating health care professionals (HCPs) provided informed written consent and received a short education session outlining the RASS-PAL administration procedure and scoring schedule. (The RASS had not been previously used on the PCU). Basic HCP demographic and patient information was collected.

The study was conducted on the 36-bed inpatient Palliative Care Unit (PCU) during working hours, Monday to Friday. Consecutive patients with an agitated delirium or receiving continuous PS were identified by attending physicians. On the PCU, if a patient screens positive on the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (Nu-DESC) [15], the attending confirms the diagnosis using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) [16] and conducts a clinical evaluation. An a priori decision was made to conduct the study in ten patients and to analyze the data. This number of patients was felt to be adequate in terms of collecting sufficient data points for inter-rater exploration in this pilot study.

Patients were evaluated every hour for the first 4 hours (T1, T2, T3 and T4) on Day 1 and then 24 hours after T4 (T5). At each time point, one physician and one bedside nurse (BSN) and/or Practice Support Nurse (PSN) observed the patient simultaneously but independently, to remain blinded to the others’ results. The intent was for the same physician/nurse team to perform all five of the assessments for an individual patient. After completing their score raters could discuss their respective scores, but not alter it, and adjust patient management if needed. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated to measure the degree of agreement among raters for T1-T5. SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for the statistical analysis.

Initially minor modifications to the RASS were made; the scale remained unchanged but the descriptors related to ‘pulling tubes’ and ‘fighting the ventilator’ were modified as these are usually not applicable in the palliative care context. Although the initial plan was to conduct a single study, a second study was conducted when the results showed that further minor modifications were required prior to validating the RASS-PAL in the palliative care context [17]. This modification to the research plan was approved by the Research Ethics Boards. This component of the study is referred to as the “Follow-up” study. In the “Initial” study, four palliative care physicians, eight BSN and one PSN participated. The intraclass correlation coefficient ranged from 0.76 to 0.95. However themes from interview data revealed the need to exclude ‘physical stimulation’ as HCPs felt this to be inappropriate. The need to standardize the scoring of patients with episodes of mixed delirium (with both agitated and hypoactive features) was also identified, as was the need for more education on the role of the tool.

In the “Follow-up” study, the instrument was modified so as to clarify that ‘any movement’ refers to eye or body, and ‘physical stimulation’ was changed to ‘gentle’ physical stimulation. For the ‘Procedure for Assessment’, the observation period was changed from 30 seconds to 20 seconds (as utilized by Ely) [6]. Clarification was also added on how to score a patient with a mixed type delirium. (See Additional file 1: Figure S1 and Additional file 2: Table S2 for the RASS-PAL tool). Otherwise, the research methods in the “Follow-Up” study were the same as in the “Initial” study.

Towards the final stages of the study, participating HCPs completed a brief written survey consisting of seven questions with a 5-point Likert Scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Questions comprised the ease of using the RASS-PAL instrument, how well the scale measured sedation and agitation, whether the scale assisted in the monitoring of patients for sedation purposes and patients with an agitated delirium, and whether the scale improved patient care and aided health care professional communication. Trained research assistants (MY, SZ) conducted the HCP semi-structured interviews (10-15 minute duration). These were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and then cleared of any identifying information. Each interview was guided by four questions: the clinical advantages and limitations of the RASS-PAL in a palliative care inpatient population, its role in patient care and suggestions to improve it.

Transcribed interviews were coded manually and then imported into NVivo version 9 (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia) for data analysis. As the interviews followed a very brief interview guide designed predominantly to gather evidence for face and construct validity for the RASS-PAL, we drew on a thematic analysis strategy to access accounts of how HCPs responded to the tool overall [18–20]. Two members of the research team (SB and MY) thematically coded an initial subset of three interview transcripts independently before reviewing their line by line coding together and building working definitions of each of their themes. Drawing on early themes grounded in the data, the team went back into the data to independently code the remaining data. All transcripts were reviewed to ensure coding consensus. Any differences in coding were reviewed and discussed until the team reached consensus. An external qualitative researcher (PG) then reviewed and applied the fully conceptualized coding tree to the data to ensure that codes had been consistently applied across the whole data set. An audit trail was utilized across the study, and detailed and comprehensive descriptions were used to describe and document the themes as they arose in the analysis [21]. A study journal was also kept, documenting any relevant findings or insights as the study progressed.

Results

Results of the “Follow-up” study are reported here. Five palliative care physicians, eight nurses (seven BSNs and one PSN) participated. Three physicians had 15 years or more experience working in palliative care, one had 6-9 years, and one had 2-5 years. Three nurses had 15 years or more experience, two had 6-9 years, and three had 2-5 years. Of the patients identified for the study, one was excluded due to deafness and impaired vision as they were not able to respond to verbal commands or visual cues [5, 6]. The included patients (eight male and two female) had a mean age of 73.6 years (range 56-88 years). Nine patients had metastatic cancer, and one patient had end-stage Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS).

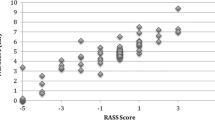

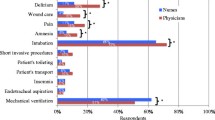

Table 1 shows the RASS-PAL scores for the ten patients. The RASS-PAL scores of patient ID10 were excluded from the final analysis due to significant time lags between raters’ assessments, as inter-rater reliability has been shown to be reduced if the time between paired assessments is more than 15 minutes [8]. There were 35 RASS-PAL observation time points with two to three raters present for the nine included patients; with a total of 89 assessment events. The inter-rater intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for T1-T5 for these nine patients were 0.98, 0.84, 0.94, 0.97 and 0.98 respectively (Table 2). The results of the 13 completed surveys are shown in Figure 1 with data from the single PSN reported as aggregate data with the BSN data to ensure anonymity.

Thirteen interviews were conducted. Three primary themes (Figure 2) emerged from this data: (1) Strengths and (2) Limitations of the tool in the PCU; and (3) Potential to improve patient care. With respect to (1), ease or utility of the instrument was identified as was its ability to facilitate the use of a common language, definitions and understanding. Tables 3 and 4 provide qualitative quotes to support this analysis, as well as quotes for the other emerging themes. Professionals across all three disciplines expressed that the RASS-PAL was easy to use, simple and brief. Clearly articulated within many of these comments was the importance of ‘ease’ and simplicity in rolling out tools for HCPs to use on the PCU. While many clinical practice tools do not always define the concepts they are using, the RASS-PAL is considered a particularly strong tool, as each level of sedation or agitation is defined. Clinical advantages ascribed to the RASS-PAL generally related to how HCPs felt the tool could inform practice. Many identified the challenges of measuring and communicating clinical findings related to sedation and agitation levels in a standardized way in daily practice. Professionals felt that using the RASS-PAL tool created a common language for team members, which would also help standardize a working definition for sedation and agitation. This standardization was deemed very important because of the subjectivity in this area and the variability amongst team members of understandings and definitions of sedation and agitation on the PCU.

With respect to (2), limitations in using it to monitor agitated or mixed-type delirium were identified. One physician cautioned that the motor ‘agitation’ as assessed by the RASS-PAL at a single point in time was not a direct measure for ‘agitated delirium’. A longer period of observation was needed to enable identification of other delirium diagnostic features. Professionals reported that it was much more challenging to use the RASS-PAL in patients with mixed delirium. Study field notes showed that nurses struggled to rate a patient with mixed delirium who was observed to be drowsy. As another limitation, some nursing professionals expressed concern that utilizing such an instrument would add to their burden of daily completion and concomitant paperwork required for other instruments on the PCU as part of a recent local quality initiative i.e. ESAS [23] and Nu-DESC [15].

The majority of HCPs felt that the tool had the potential to improve patient care. However, some stipulated that patient care would only improve if the tool was used to inform clinical therapies and practices within the team.

“Yeah I mean…in so much as it can create a common language….a tool in of itself cannot change patient care. People using the tool will if they use common language together so that they’re on the same page about the sedation targets and results and…use that language as a means of titrating their therapy”. (Palliative Care Physician – ID 1010)

All disciplines identified the need for a broader education initiative to better orientate them to the instrument.

Discussion

This study provides preliminary validity evidence for the use of the RASS-PAL in assessing the level of sedation and agitation in palliative care inpatient populations, more specifically in the context of PS. Consistent with studies of the original RASS [5, 6], we demonstrate that the RASS-PAL has good psychometric properties with high inter-rater reliability [24] when used by HCPs on a PCU. Similarly a modified RASS (with different modifications as compared with the RASS-PAL) used in Spanish patients with advanced cancer also demonstrated very good inter-rater reliability, especially when used by experienced professionals [13].

There were general improvements in reliability utilizing the RASS-PAL as compared with our initial modified version of the RASS. Evidence for face validity was noted, although we recognize that emerging understandings of the concept of validity place less emphasis on this property. The RASS instrument modifications at the beginning of the study and following the “initial” study, and qualitative and quantitative data showing general agreement amongst HCPs on the role of the RASS-PAL, provide evidence for construct validity.

Professionals said that they were often uncomfortable with the subjectivity and ambiguity that characterize discussions between team members about sedation and agitation. It is clear that they are interested in finding working definitions of levels of sedation and agitation, which can be used across interprofessional teams, to improve communication and patient care [25–27]. The RASS-PAL tool offers a framework that can be used across interprofessional teams to effectively communicate and collaborate together as they develop a plan of care. Ensuring strong and clear communication about sedation, agitation and delirium across the interprofessional team at all times, particularly at high-risk times in terms of shift changes and handovers in care, is absolutely critical in ensuring that patients receive the best possible care [28].

Our findings differ in some key respects from previous studies [9, 13]. Chester et al. reported a modified RASS which could be utilized for daily delirium screening, but their tool incorporated an assessment of attention as part of the instrument modification [9]. Lack of attention is increasingly recognized as a key feature of delirium [29]. Our modifications did not include this feature, which may explain some of the difference in results between our study and theirs.

Agitation is not a delirium specific sign and underlying causes for agitation in the ICU setting may be different than in a PCU setting, such as ‘fighting the ventilator’ [27, 30–33]. In addition, the assessment of patients with mixed delirium remains challenging as a single assessment and corresponding score is not adequate [6]. Sessler described this as a limitation to the original RASS where patients appeared to be sleeping or sedated but responded to auditory or physical stimulation violently [5].

In our study, concerns were expressed on using the RASS-PAL for monitoring patients with delirium because of the fluctuating nature of delirium as the instrument provides in essence a ‘snap-shot’ assessment. As refractory agitated delirium is common at the end of life [14], the RASS-PAL could however play a role in providing justification for using a rescue antipsychotic dose in agitated delirium and assessing its short-term impact. The RASS and RASS-PAL are very different to delirium tools such as the Nu-DESC [15], DRS-R-98 [34], and MDAS [35] which measure delirium over an extended time-frame. The Agitation Distress Scale, designed to measure agitation distress in delirious patients at the end of life, is also rated over a 12-hour time period [33]. Delirium evaluation in the ICU setting routinely comprises the CAM-ICU in addition to the RASS [36]. Therefore, the use of the RASS-PAL to monitor or screen for delirium in the palliative care setting warrants further research before it is more broadly recommended.

Professionals noted that the RASS-PAL had the potential to improve patient care. They highlighted the possibility for it to standardize practice, enhance communication and monitoring, and encourage follow through into decision-making. Future studies should examine the full application and implementation of how the RASS-PAL is used to inform clinical decision-making as this would offer a stronger understanding about how the RASS-PAL tool actually improves patient care. The issue of the instrument adding burden to nursing care warrants discussion. It appears the source of burden is not the RASS-PAL itself, but rather the overall use of instruments on the PCU. If tools such as the RASS-PAL are completed but not used by the clinical team to inform practices, professionals will regard these tools as one more piece of paper, required, but not useful. This echoes other studies which have shown that nurses may feel that scales are time consuming and have unclear relevance for their practice and patient care [37].

Contrary to initial studies where the original RASS was administered with minimal training [5, 6] our study participants generally felt that significant formal education was required on how to integrate the RASS-PAL into clinical practice [4]. It is unlikely that the minor modifications of the RASS-PAL from the original RASS contributed to this. One possible explanation could relate to ICU nurses being more accustomed to such assessments where it is common practice to stimulate patients in order to assess sedation level in routine daily practice [26], but it is noteworthy that an educational strategy was later utilized for the large-scale implementation of the RASS [38]. Education for RASS-PAL implementation needs to emphasize both logistical and procedural elements of using the tool, as well as broader understandings of how varying HCPs perceive the tool informing their practice as well as other team members. Education strategies should be integrated education programs rather than one-time event [28, 39]. This would promote a broader understanding of how the RASS-PAL would inform practice on multiple levels.

This study highlights the merits of mixed methods research approaches. As Farquhar et al. recently noted it is an approach that is “particularly valuable in palliative care research, where the majority of interventions are complex” [40]. Drawing on a mixed method design offered an opportunity to examine the process of evaluating and identifying sedation and agitation, and the experience of HCPs in applying the tool in practice.

There are several limitations to this study. This was a small pilot study which may limit the generalizability of the results. Notwithstanding this, it does raise some important issues and contributes to building validity evidence for the RASS-PAL. Not all aspects of validity evidence required to fully examine construct validity were explored [7, 41]. On multiple occasions it was not possible for all three raters to be present for each time point, reflecting the real-life challenges of research on a PCU. As with other sedation instruments [5, 42], this study did not test the responsiveness of the RASS-PAL instrument in detecting important changes in sedation over time, nor did it specifically evaluate how utilizing the RASS-PAL will change PS practice.

Conclusions

We found that the RASS-PAL has high inter-rater reliability and appears useful in monitoring sedation level in patients receiving PS. It appears to have potential to standardize PS practice and improve interprofessional patient care. Future studies should validate the RASS-PAL against other sedation monitoring instruments and assess for other sources of validity evidence in this patient population and context of care. Although it does not specifically screen for delirium, the RASS-PAL provides a snapshot assessment in time for agitation. Further research on the feasibility of using the RASS-PAL to monitor established delirium in palliative care patients is required. Further research is also needed on its large-scale implementation in palliative care settings with multifaceted educational strategies and evaluation of ongoing reliability.

References

Cherny NI, Radbruch L: European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework for the use of sedation in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2009, 23: 581-593. 10.1177/0269216309107024.

de Graeff A, Dean M: Palliative sedation therapy in the last weeks of life: a literature review and recommendations for standards. J Palliat Med. 2007, 10: 67-85. 10.1089/jpm.2006.0139.

Dean MM, Cellarius V, Henry B, Oneschuk D, Librach SL, Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians Taskforce: Framework for continuous palliative sedation therapy in Canada. J Palliat Med. 2012, 15: 870-879. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0498.

Brinkkemper T, van Norel AM, Szadek KM, Loer SA, Zuurmond WW, Perez RS: The use of observational scales to monitor symptom control and depth of sedation in patients requiring palliative sedation: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2013, 27: 54-67. 10.1177/0269216311425421.

Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O'Neal PV, Keane KA, Tesoro EP, Elswick RK: The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 166: 1338-1344. 10.1164/rccm.2107138.

Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, Thomason JW, Wheeler AP, Gordon S, Francis J, Speroff T, Gautam S, Margolin R, Sessler CN, Dittus RS, Bernard GR: Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA. 2003, 289: 2983-2991. 10.1001/jama.289.22.2983.

Cook DA, Beckman TJ: Current concepts in validity and reliability for psychometric instruments: theory and application. Am J Med. 2006, 119 (166): e7-e16.

Arevalo JJ, Brinkkemper T, van der Heide A, Rietjens JA, Ribbe M, Deliens L, Loer SA, Zuurmond WW, Perez RS, AMROSE Site Study Group: Palliative sedation: reliability and validity of sedation scales. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012, 44: 704-714. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.11.010.

Chester JG, Beth Harrington M, Rudolph JL, VA Delirium Working Group: Serial administration of a modified Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale for delirium screening. J Hosp Med. 2012, 7: 450-453. 10.1002/jhm.1003.

Elsayem A, Curry E, Boohene J, Munsell MF, Calderon B, Hung F, Bruera E: Use of palliative sedation for intractable symptoms in the palliative care unit of a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2009, 17: 53-59. 10.1007/s00520-008-0459-4.

Maltoni M, Miccinesi G, Morino P, Scarpi E, Bulli F, Martini F, Canzani F, Dall'Agata M, Paci E, Amadori D: Prospective observational Italian study on palliative sedation in two hospice settings: differences in casemixes and clinical care. Support Care Cancer. 2012, 20: 2829-2836. 10.1007/s00520-012-1407-x.

Benitez-Rosario MA, Castillo-Padrós M, Garrido-Bernet B, Ascanio-León B: Quality of care in palliative sedation: audit and compliance monitoring of a clinical protocol. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012, 44: 532-541. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.10.029.

Benitez-Rosario MA, Castillo-Padrós M, Garrido-Bernet B, González-Guillermo T, Martínez-Castillo LP, González A, Members of the Asocación Canaria de Cuidados Paliativos (CANPAL) Research Network: Appropriateness and reliability testing of the modified Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale in Spanish patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013, 45: 1112-1119. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.05.015.

Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Rosati M, Derni S, Fabbri L, Martini F, Amadori D, Nanni O: Palliative sedation in end-of-life care and survival: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 30: 1378-1383. 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.3795.

Gaudreau JD, Gagnon P, Harel F, Tremblay A, Roy MA: Fast, systematic, and continuous delirium assessment in hospitalized patients: the nursing delirium screening scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005, 29: 368-375. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.07.009.

Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI: Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method: a new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990, 113: 941-948. 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941.

Bush SH, Palacios M, Yarmo MN, Sinden D, Pereira J: Pilot testing of a Modified Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) instrument on a palliative care inpatient unit. Support Care Cancer. 2010, 18 (Suppl 3): S156-S157.

Boyatzis R: Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. 1998, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications

Fossey E, Harvey C, McDermott F, Davidson L: Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002, 36: 717-732. 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01100.x.

Guba E, Lincoln Y: Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Edited by: Denzin N, Lincoln Y. 2005, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 191-215. 3

Lincoln Y, Guba E: Naturalistic Inquiry. 1985, Newbury Park: Sage

Downing GM, Wainright W: Medical Care of the Dying. Victoria Hospice: Palliative Performance Scale (PPSv2) version 2. 2006, Vancouver: Victoria Hospice Society: Learning Centre for Palliative Care, 120-121. 4

Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K: The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991, 7: 6-9.

Landis JR, Koch GG: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977, 33: 159-174. 10.2307/2529310.

Sessler CN: Use of sedation assessment scales in the ICU: Paying attention to what we are doing. Proceedings from The Sixth Conference, Center for Safety and Clinical Excellence, 2005. 2005, San Diego: Sedation therapy: Improving safety and quality of care, 6-9.

Mirski MA, LeDroux SN, Lewin JJ, Thompson CB, Mirski KT, Griswold M: Validity and reliability of an intuitive conscious sedation scoring tool: the nursing instrument for the communication of sedation. Crit Care Med. 2010, 38: 1674-1684. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e7c73e.

Egerod I: Uncertain terms of sedation in ICU: how nurses and physicians manage and describe sedation for mechanically ventilated patients. J Clin Nurs. 2002, 11: 831-840. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00725.x.

Agar M, Draper B, Phillips PA, Phillips J, Collier A, Harlum J, Currow D: Making decisions about delirium: a qualitative comparison of decision making between nurses working in palliative care, aged care, aged care psychiatry, and oncology. Palliat Med. 2012, 26: 887-896. 10.1177/0269216311419884.

Meagher D, Adamis D, Trzepacz P, Leonard M: Features of subsyndromal and persistent delirium. Br J Psychiatry. 2012, 200: 37-44. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095273.

Jacobi J, Fraser GL, Coursin DB, Riker RR, Fontaine D, Wittbrodt ET, Chalfin DB, Masica MF, Bjerke HS, Coplin WM, Crippen DW, Fuchs BD, Kelleher RM, Marik PE, Nasraway SA, Murray MJ, Peruzzi WT, Lumb PD, Task Force of the American College of Critical Care Medicine (ACCM) of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), American College of Chest Physicians: Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med. 2002, 30: 119-141. 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00020.

Sessler CN, Grap MJ, Ramsay MA: Evaluating and monitoring analgesia and sedation in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2008, 12 (Suppl 3): S2-10.1186/cc6148.

Morita T, Tei Y, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S: Underlying pathologies and their associations with clinical features in terminal delirium of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001, 22: 997-1006. 10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00360-8.

Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S, Oka K: Communication Capacity Scale and Agitation Distress Scale to measure the severity of delirium in terminally ill cancer patients: a validation study. Palliat Med. 2001, 15: 197-206. 10.1191/026921601678576185.

Trzepacz PT, Mittal D, Torres R, Kanary K, Norton J, Jimerson N: Validation of the Delirium Rating Scale-revised-98: comparison with the delirium rating scale and the cognitive test for delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001, 13: 229-242. 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13.2.229.

Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Roth A, Smith MJ, Cohen K, Passik S: The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997, 13: 128-137. 10.1016/S0885-3924(96)00316-8.

Mistraletti G, Pelosi P, Mantovani ES, Berardino M, Gregoretti C: Delirium: clinical approach and prevention. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2012, 26: 311-326. 10.1016/j.bpa.2012.07.001.

Soden K, Ali S, Alloway L, Barclay D, Perkins P, Barker S: How do nurses assess and manage breakthrough pain in specialist palliative care inpatient units? A multicentre study. Palliat Med. 2010, 24: 294-298. 10.1177/0269216309355918.

Pun BT, Gordon SM, Peterson JF, Shintani AK, Jackson JC, Foss J, Harding SD, Bernard GR, Dittus RS, Ely EW: Large-scale implementation of sedation and delirium monitoring in the intensive care unit: a report from two medical centers. Crit Care Med. 2005, 33: 1199-1205. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000166867.78320.AC.

Ramaswamy R, Dix EF, Drew JE, Diamond JJ, Inouye SK, Roehl BJ: Beyond grand rounds: a comprehensive and sequential intervention to improve identification of delirium. Gerontologist. 2011, 51: 122-131. 10.1093/geront/gnq075.

Farquhar MC, Ewing G, Booth S: Using mixed methods to develop and evaluate complex interventions in palliative care research. Palliat Med. 2011, 25: 748-757. 10.1177/0269216311417919.

Downing SM: Validity: on meaningful interpretation of assessment data. Med Educ. 2003, 37: 830-837. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01594.x.

De Jonghe B, Cook D, Appere-De-Vecchi C, Guyatt G, Meade M, Outlin H: Using and understanding sedation scoring systems: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2000, 26: 275-285. 10.1007/s001340051150.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-684X/13/17/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our physician and nursing colleagues who participated in this study. We also thank Dr. Neil MacDonald who reviewed an earlier draft of this manuscript.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Presented in part as a poster at the 7th World Research Congress of the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC), Trondheim, Norway: June 7-9, 2012

Poster abstract published as:

Bush SH, Yarmo MN, Grassau PA, Zhang T, Zinkie SJ, Pereira J. The validation and feasibility of using a palliative care modified Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS-PAL) instrument in a palliative care inpatient unit: A pilot study. 7th World Research Congress of the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC), June 7-9, 2012: Trondheim, Norway. Palliat Med 2012; 26(4):467 (P36).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SB participated in the design of the study, performed the qualitative statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. PG participated in the qualitative statistical analysis, the interpretation of this data and helped to draft the manuscript. MY conducted participant interviews, participated in the study coordination and performed the qualitative statistical analysis. TZ performed the quantitative statistical analysis. SZ conducted participant interviews and participated in the study coordination. JP conceived of the study, and participated in its design and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Bush, S.H., Grassau, P.A., Yarmo, M.N. et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale modified for palliative care inpatients (RASS-PAL): a pilot study exploring validity and feasibility in clinical practice. BMC Palliat Care 13, 17 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-13-17

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-13-17