Abstract

Purpose

Palliative sedation (PS) has been defined as the use of sedative medications to relieve intolerable suffering from refractory symptoms by a reduction in patient consciousness. It is sometimes necessary in end-of-life care when patients present refractory symptoms. We investigated PS for refractory symptoms in different hospice casemixes in order to (1) assess clinical decision-making, (2) monitor the practice of PS, and (3) examine the impact of PS on survival.

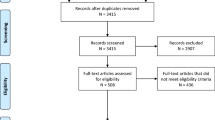

Methods

This observational longitudinal cohort study was conducted over a period of 9 months on 327 patients consecutively admitted to two 11-bed Italian hospices (A and B) with different casemixes in terms of median patient age (hospice A, 66 years vs. hospice B, 73 years; P = 0.005), mean duration of hospice stay (hospice A, 13.5 days vs. hospice B, 18.3 days; P = 0.005), and death rate (hospice A, 57.2% vs. hospice B, 89.9%; P < 0.0001). PS was monitored using the Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale (RASS). Sedated patients constituted 22% of the total admissions and 31.9% of deceased patients, which did not prove to be significantly different in the two hospices after adjustment for casemix.

Results

Patient involvement in clinical decision-making about sedation was significantly higher in hospice B (59.3% vs. 24.4%; P = 0.007). Family involvement was 100% in both hospices. The maximum level of sedation (RASS, −5) was necessary in only 58.3% of sedated patients. Average duration of sedation was similar in the two hospices (32.2 h [range, 2.5–253.0]). Overall survival in sedated and nonsedated patients was superimposable, with a trend in favor of sedated patients.

Conclusions

PS represents a highly reproducible clinical intervention with its own indications, assessment methodologies, procedures, and results. It does not have a detrimental effect on survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Costantini M, Beccaro M, Merlo F, Study Group ISDOC (2005) The last three months of life of Italian cancer patients. Methods, sample characteristics and response rate of the Italian Survey of the Dying of Cancer (ISDOC). Palliat Med 19:628–638

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A et al (2005) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733–742

Cherny N, Catane R, Schrijvers D, Kloke M, Strasser F (2010) European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) program for the integration of Oncology and Palliative Care: a 5-year review of the Designated Centers’ incentive program. Ann Oncol 21:362–369

Van der Heide A, Deliens L, Faisst K et al (2003) End-of-life decision-making in six European countries: descriptive studies. Lancet 362:345–350

De Graeff A, Dean M (2007) Palliative sedation therapy in the last weeks of life: a literature review and recommendations for standards. J Palliat Med 10:67–85

Carr MF, Mohr GJ (2008) Palliative sedation as part of a continuum of palliative care. J Palliat Med 11:76–81

Maltoni M, Pittureri C, Scarpi E et al (2009) Palliative sedation therapy does not hasten death: results from a prospective multicenter study. Ann Oncol 20:1163–1169

Sykes N, Thorns A (2003) The use of opioids and sedation at the end of life. Lancet Oncol 4:312–318

Materstvedt LJ, Clark D, Ellershaw J et al (2003) Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a view from an EAPC Ethics Task Force. Palliat Med 17:97–101

Miccinesi G, Rietjens J, Deliens L et al (2006) Continuous deep sedation: physicians’ experiences in six European countries. J Pain Symptom Manag 31:122–129

Cherny NI, Portenoy RK (1994) Sedation in the management of refractory symptoms: guidelines for evaluation and treatment. J Palliat Care 10:31–38

Cherny NI, Radbruch L, Board of the European Association for Palliative Care (2009) European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework for the use of sedation in palliative care. Palliat Med 23:581–593

Kirk TW, Mahon MM, Palliative Sedation Task Force of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Ethics Committee (2010) National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) position statement and commentary on the use of palliative sedation in imminently dying terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 39:914–923

van Dooren S, van Veluw HT, van Zuylen L et al (2009) Exploration of concerns of relatives during continuous palliative sedation of their family members with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag 38:452–459

Morita T, Akechi T, Sugawara Y et al (2002) Practices and attitudes of Japanese oncologists and palliative care physicians concerning terminal sedation: a nationwide survey. J Clin Oncol 20:758–764

Schuman-Oliver Z, Brendel DH, Forstein M, Price BH (2008) The use of palliative sedation for existential distress: a psychiatric perspective. Harv Rev Psychiatr 16:339–351

Kaplan EL, Meier P (1958) Non parametric estimation for incomplete observation. J Am Stat Assoc 53:457–481

Lawless JS (1982) Statistical models and methods for life-time data. Wiley, New York

Ventafridda V, Ripamonti C, De Conno F, Tamburini M, Cassileth BR (1990) Symptom prevalence and control during cancer patients’ last days of life. J Palliat Care 6:7–11

Porta Sales J (2001) Sedation and terminal care. Eur J Palliat Care 8:97–100

Peruselli C, Di Giulio P, Toscani F et al (1999) Home palliative care for terminal cancer patients: a survey on the final week of life. Palliat Med 13:233–241

Fainsinger RL, Waller A, Bercovici M et al (2000) A multicentre international study of sedation for uncontrolled symptoms in terminally ill patients. Palliat Med 14:257–265

Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap J et al (2002) The Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale. Validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166:1338–1344

Bruera E, Sala R, Rico MA et al (2005) Effects of parenteral hydration in terminally ill cancer patients: a preliminary study. J Clin Oncol 23:2366–2371

Good P, Cavenagh J, Mather M, Ravenscroft P (2008) Medically assisted hydration for palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD006273

Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S (2001) Effects of high dose opioids and sedatives on survival in terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 21:282–289

Morita T, Chinone Y, Ikenaga M et al (2005) Efficacy and safety of palliative sedation therapy: a multicenter, prospective, observational study conducted on specialized palliative care units in Japan. J Pain Symptom Manag 30:320–328

Acknowledgements

Funding was received from the Italian Ministry of Health as part of the Oncology Research Project “Ricerca Sanitaria Finalizzata ex art. 12 D.Lgs. 502/92, 2006. Programma Integrato Oncologia (area tematica 6)”. The funding source was not involved in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. The authors thank Gráinne Tierney for editing the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale (RASS)

RASS description

+4 Combative, violent, danger to staff

+3 Pulls or removes tube(s) or catheters; aggressive

+2 Frequent nonpurposeful movement, fights ventilator

+1 Anxious, apprehensive, but not aggressive

0 Alert and calm

−1 Awakens to voice (eye opening/contact) >10 s

−2 Light sedation, briefly awakens to voice (eye opening/contact) <10 s

−3 Moderate sedation, movement or eye opening; no eye contact

−4 Deep sedation, no response to voice, but movement or eye opening to physical stimulation

−5 Unarousable, no response to voice or physical stimulation

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maltoni, M., Miccinesi, G., Morino, P. et al. Prospective observational Italian study on palliative sedation in two hospice settings: differences in casemixes and clinical care. Support Care Cancer 20, 2829–2836 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1407-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1407-x