Abstract

Background

Our aim was to obtain a clearer picture of the relevant care experiences and care perceptions of incurably ill Turkish and Moroccan patients, their relatives and professional care providers, as well as of communication and decision-making patterns at the end of life. The ultimate objective is to improve palliative care for Turkish and Moroccan immigrants in the Netherlands, by taking account of socio-cultural factors in the guidelines for palliative care.

Methods

A systematic literature review was undertaken. The data sources were seventeen national and international literature databases, four Dutch journals dedicated to palliative care and 37 websites of relevant national and international organizations. All the references found were checked to see whether they met the structured inclusion criteria. Inclusion was limited to publications dealing with primary empirical research on the relationship between socio-cultural factors and the health or care situation of Turkish or Moroccan patients with an oncological or incurable disease. The selection was made by first reading the titles and abstracts and subsequently the full texts. The process of deciding which studies to include was carried out by two reviewers independently. A generic appraisal instrument was applied to assess the methodological quality.

Results

Fifty-seven studies were found that reported findings for the countries of origin (mainly Turkey) and the immigrant host countries (mainly the Netherlands). The central themes were experiences and perceptions of family care, professional care, end-of-life care and communication. Family care is considered a duty, even when such care becomes a severe burden for the main female family caregiver in particular. Professional hospital care is preferred by many of the patients and relatives because they are looking for a cure and security. End-of-life care is strongly influenced by the continuing hope for recovery. Relatives are often quite influential in end-of-life decisions, such as the decision to withdraw or withhold treatments. The diagnosis, prognosis and end-of-life decisions are seldom discussed with the patient, and communication about pain and mental problems is often limited. Language barriers and the dominance of the family may exacerbate communication problems.

Conclusions

This review confirms the view that family members of patients with a Turkish or Moroccan background have a central role in care, communication and decision making at the end of life. This, in combination with their continuing hope for the patient’s recovery may inhibit open communication between patients, relatives and professionals as partners in palliative care. This implies that organizations and professionals involved in palliative care should take patients’ socio-cultural characteristics into account and incorporate cultural sensitivity into care standards and care practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Palliative care has seen considerable development in Western countries in the past few decades, and the number of hospices and other institutions specializing in palliative care has been growing [1–3]. Initially palliative care was mainly associated with care for terminally ill cancer patients. In recent years however, palliative care has expanded, including patients with non-malignant, progressive and life-limiting conditions such as heart failure and COPD [4]. Furthermore, palliative care providers and researchers increasingly pay attention to patients with specific cultural and socio-demographic characteristics, such as patients with a non-Western background. This is illustrated by the fact that in 2002 the World Health Organization clearly stated that guidelines on palliative care in all countries have to be adapted to cultural contexts [5].

Studies of palliative care conducted in non-Western countries have pointed to patients’ limited choices with regard to obtaining adequate pain relief and medication because of poverty [6–8]. Family care systems, religious practices and traditional care perceptions may influence the use of palliative care. Cultural minorities living in Western countries may face inadequate palliative care because of language differences [9], health literacy difficulties [10] or experiences of discrimination [11, 12]. The supply of palliative care may not always meet the care expectations of immigrants due to their specific cultural or religious background [13–15]. Research among Sikh and Muslim patients with life-limiting illnesses living in Europe revealed that these immigrant patients are often reluctant to seek help from professional caregivers or institutions, rather than care from their own family and close relatives, because of negative experiences with care services (such as unacceptable food and racism) and concern about criticism from their community. Besides, communication with professionals was often hampered since illness and suffering were viewed as God’s will [16].

In our empirical research in the Netherlands over the period 2001 to 2009 we found care professionals often see specific care needs and communication problems when delivering palliative care to immigrant patients [17, 18]. They often find it difficult to assess and meet the needs of these patients and their families, due to the patient’s lack of knowledge about the disease, cultural patterns within family relationships and inadequate formal or informal interpreter facilities. Turkish and Moroccan people form the largest immigrant groups in the Netherlands [19]. The ethnic roots of Turkish and Moroccan immigrants are diverse. However, most of them share important features such as coming from poor agricultural regions, arriving as low-paid ‘guest workers’ between 1965 and 1980, and living in deprived neighbourhoods as a Muslim minority. The first generations of Turkish and Moroccan immigrants are ageing now, and more and more of these people will start to need palliative care. An earlier literature study on the care needs of the Turkish and Moroccan elderly revealed that they often experienced barriers to making use of Dutch professional care, e.g. because of the strong role of family care in their cultures [20]. However, at that time we did not find any publications about Turkish and Moroccan people in the palliative phase. Since the number of patients in these groups needing palliative care will have increased since then, and accordingly the number of relevant studies can be expected to have grown, we decided to reinvestigate the international literature on Turkish and Moroccan incurably ill patients.

The questions addressed in this systematic literature review are:

What is known from previous research about

-

a)

the care experiences and care perceptions of incurably ill Turkish and Moroccan patients, their relatives and care professionals?

-

b)

communication between these patients, relatives and care professionals regarding care and treatment in the palliative phase?

Methods

A systematic review was performed in several steps to find research literature about care perceptions and communication in the care for Turkish or Moroccan incurably ill patients. In this review we used the term ‘incurably ill Turkish or Moroccan patients’ to refer to people with a Turkish or Moroccan background, whether living in Turkey or Morocco or living in the Netherlands or another immigrant host country, who suffer from an incurable life-threatening disease. A person is defined as having a Turkish or Moroccan background if they were ‘born in Turkey or Morocco (with at least one parent born in Turkey or Morocco) or born outside Turkey or Morocco but with at least one parent born in Turkey or Morocco’.

Searches

We searched for both qualitative and quantitative studies. Three main sources were used to find the literature: 17 national and international literature databases, four Dutch journals dedicated to palliative care and 37 websites for relevant national and international organizations. Additional file 1 gives the details of all sources. Additionally, members of the project team were asked for relevant publications and references listed in review articles were checked. The search string below was used for Pubmed. Searches for the other databases were derived from this Pubmed search string and adjusted where necessary (these are available on request).

" (“End-of-life” OR palliative OR hospice OR dying OR death OR "Advance Care Planning"[Mesh] OR "Hospice Care"[Mesh] OR "Palliative Care"[Mesh] OR "Withholding Treatment"[Mesh] OR "Terminal Care"[Mesh] OR "Euthanasia"[Mesh] OR “palliative sedation” OR “truth telling“ OR “truth disclosure” OR “advance directives”) AND (culture specific* OR culturally specific* OR diversity specific* OR culture sensitive* OR culturally sensitive* OR diversity sensitive* OR culturally divers* OR cultural aspect* OR cultural competen* OR “cultural context” OR racial OR etnic minorit* OR etnic specific* OR ethnic minorit* OR ethnic specific* OR “ethnic background” OR “etnic background” OR cross?cultural OR crosscultural OR trans?cultural OR transcultural OR intercultural OR inter?cultural OR multicultural OR multi?cultural OR indigeneous OR indiginous OR immigrant* OR migrant* OR ethnicity OR acculturation OR islam* OR Muslim* OR Hindu* OR Winti OR (Moroc* [tiab] OR Maroc* [tiab] OR Turk* [tiab] OR Surinam* [tiab] OR Antill* [tiab] OR aruba* [tiab] OR caribb* [tiab])) AND ("2000"[PDAT] : "2010"[PDAT]) "

Manual searches were performed in specific journals (see Additional file 1). Relevant websites were searched without a predefined search strategy. Searches were limited to publications dating from 2000 onwards, since we found little relevant literature on the topic in our earlier literature study [20]. No language restrictions were applied. Although the searches were initially somewhat broader and aimed at finding literature on five immigrant groups in the Netherlands (see the search string above), it appeared that very few publications could be traced about the other three immigrant groups, so we restricted the inclusion criteria further to just Turkish and Moroccan people for the purpose of this paper.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All the references obtained in this way were then checked to see whether they met the inclusion criteria. This was done first on the basis of the title/abstract and later on the basis of the full text of the documents. The inclusion process was carried out by two reviewers independently and disagreements were solved by discussion.

The inclusion criteria applied were as follows:

It is a primary empirical research paper.

The publication is about socio-cultural factors concerning Turkish or Moroccans subjects. Socio-cultural factors are factors that might affect the feelings and behaviours of groups with regard to care values and care practices, family and kinships structures as well as their attitude towards professional care. We included publications on Turkish and Moroccan patients in their countries of origin in addition to publications on Turkish and Moroccan immigrants in host countries.

A relationship between a socio-cultural factor and health (or care) outcomes was studied.

The paper concerns patients and/or carers of patients with an oncologic or incurable disease and/or in the palliative phase.

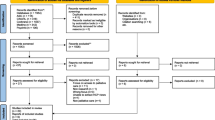

Exclusion criteria were letters/editorials, publications on organ donation, perinatology, near-death experiences, death row or mourning. All searches were done in May 2010. The inclusion flow diagram is depicted in Figure 1.

Appraisal of the methodological quality

The methodological quality of the studies satisfying the inclusion criteria was checked. Since publications using different types of research methods (both qualitative and quantitative) were included, a generic appraisal instrument was applied [21]. This was chosen because it was specifically developed to appraise publications of disparate kinds of data. It consists of nine items (abstract, background, method, sampling, data analysis, ethics, results, transferability and implications); each item is scored on a 4-point scale from very poor to good (total scores may vary from 9 to 36; scores less than or equal to 18 were considered as ‘poor methodological quality’, from 19 to 27 ‘moderate’ and above 27 ‘good quality’). The methodological assessment was done by one researcher [PM] and 50% of the references were also checked independently by a second reviewer [AF, WD] (in this case the mean of the two scores was computed). Reviewers were assigned in such a way that they never had to judge documents of which they were a co-author. The publications in the Turkish language were assessed by a native Turkish psychologist. A low methodological score was not used as an exclusion criterion, but studies with such a low score were checked if they presented results that contradicted the results in other studies.

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis

Data were extracted from each included publication by one reviewer and checked by a second. Data were extracted about the type of research, nature and size of the research population (ethnic group, professionals/patients/relatives, disease), country where the research was done, research questions and results.

Data from the publications that related to the review questions were extracted and classified in themes, which were then discussed in the research team. We analysed and synthesized the data in various ways, looking for contrasts: between Turkish and Moroccan patients, between experiences in countries of origin and experiences in host countries, between different care belief issues, between issues concerning care in practice and communication issues, and between the different phases that patients go through in the course of their illness. We concluded that the relevant data could best be presented in using the themes shown in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4. For each theme, data from different populations (Turkish/Moroccan/mixed group of immigrants) and perspectives (patients/relatives/professionals) were described and summarized. If possible, a distinction was made between the different immigrant groups and between data concerning the countries of origin and data concerning the immigrant host countries.

Results

Characteristics of the studies included

Sixty-four publications [17, 18, 20, 22–83] were included concerning 57 studies. Some studies were presented in more than one publication. In those cases we used the main publication for the description of the characteristics and study findings.

Language and place of study

All studies were published in the period 2000 to 2010. Most of the 57 studies were published in English (39), one was in French [52] one in German [56], two were in Turkish [31, 64], and fourteen in Dutch.

Forty studies addressed the experiences of Turkish subjects. Seven of these forty studies concerned immigrants with a Turkish background either living in Germany (one study), Belgium (one study) or the Netherlands (five studies). Of the 33 studies of Turkish people living in Turkey, five studies were performed in provinces in Eastern Turkey, but most concerned the situation in modern cities in Western or Central Turkey.

Four studies focused on Moroccans in Morocco and addressed the experiences of people living in Rabat and Casablanca, two large cities in Morocco with specialized cancer care.

Additionally, we found thirteen studies of Turkish and Moroccan immigrants in the Netherlands. Four of these thirteen studies focused on Turkish and Moroccan immigrants only, while the other nine presented data about several immigrant groups living in the Netherlands, including Moroccan and Turkish immigrants.

Research questions and subjects

Most research questions addressed the needs or attitudes of care users or care providers, the problems of care professionals or relatives, or factors influencing the access to or the quality of care.

Patient perspectives were described in 22 of the 57 studies, relatives were involved in 15 studies, physicians in 23 studies and nurses in 17 studies. Some studies combined the perspectives of patients and relatives, for example when relatives were asked to describe the views of their ill patients [17, 22, 33]. Some studies combined the perspectives of relatives and professionals [23, 26, 59, 66]. Other studies compared the views of patients and relatives with the views of professionals [18, 45, 48, 69] or compared the views of physicians with the views of nurses [40, 75].

Designs, sample sizes and instruments

Many studies (35 of the 57) had a quantitative design, often using self-developed survey questionnaires. However, three studies [29, 30, 34] used existing instruments, namely the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, the Barriers Questionnaire II (BQ-II) or the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Twenty studies had a qualitative design, generally using semi-structured interviews or focus groups. Two studies used a mixed design. Studies performed in Turkey and Morocco were often quantitative in nature, involving large samples: e.g. 150–1,000 Turkish professionals or 600–1,600 Moroccan patients. Sample sizes in studies performed among Turkish or Moroccan immigrants in Europe were often smaller (less than 20 research subjects), related to the fact that these studies often had a qualitative design (see Table 5). One exception is the study by VPTZ (Vrijwilligers Palliatieve Terminale Zorg Nederland = Volunteers for palliative care in the Netherlands) describing focus groups with a total of 255 Moroccan and Turkish relatives.

Methodological quality

As said, the methodological quality of all the selected publications was assessed by one reviewer and half of the publications by a second reviewer as well. Scores from the first reviewer varied between 12 and 36 with a mean of 25 (see the Methods section for the range). Those from the second reviewer ranged from 16 to 36 with a mean of 27.4. The Pearson correlation between the scores of the two reviewers was 0.75 (p < 0.05). Cohen’s kappa for the between the category scores was also significant (p < 0.05).

The total score for each study is presented in Table 5 (the mean score is presented for studies assessed by both reviewers). Six studies fell in the ‘low methodological quality’ category, 32 in the ‘moderate’ category and 19 in the ‘good quality’ category. The aspects most frequently given a low score were ‘background and clear statement of the research aims’, ‘addressing ethical issues’ and ‘sampling strategy’. The six studies [23, 28, 37, 52, 60, 74] with low scores did not show results that were fundamentally different or contradictory to the other results and are therefore not excluded or treated differently in the synthesis.

We felt that the findings from our study could best be presented by clustering them into four themes, namely the experiences and perceptions regarding family care, those regarding professional care, those regarding end-of life care and decision making, and finally the experiences and perceptions regarding communication in end-of-life care.

Findings related to perspectives regarding family care

Seventeen studies addressed the contribution of family members in the care for incurable Turkish or Moroccan patients. Three topics were mentioned frequently: family care is seen as (1) a social duty, (2) an economic necessity, and (3) a burden.

Family care as a duty

All studies – whether they were performed in the countries of origin or in the host immigrant countries - indicate that family members are key care providers. For example, it was shown by studies conducted in Turkey that family care is a duty [28], and that Turkish patients are mainly cared for by the family [68]. In addition, studies performed in Morocco showed that most patients (92%) were supported by the family [50, 52]. Studies performed in the Netherlands also stress that Turkish and/or Moroccan patients and their relatives consider family care as an obvious duty [17, 55, 80, 81]. Many patients expected their children and their children’s partners to take care of them. In practice daughters or daughters-in-law did most of the work [17, 55, 81, 82]. Family care involved activities like preparing food all through the day for the patient and for the many visitors, doing the paperwork, accompanying the patient to the doctor as an interpreter and providing personal care [55, 65, 81].

Family care as an economic necessity

Some studies – performed in the home countries - noted that the emphasis on family care is also the result of poverty. In Turkey, families’ poverty and hospitals’ lack of resources were seen as problem by physicians [40]. In Morocco, cancer patients said that professional treatment was frequently compromised by poverty and lack of medical insurance [50, 52]. Often families had insufficient monthly income to pay for professional medical treatment.

Family care as a burden

Family care is considered burdensome - especially in the Dutch studies. Studies conducted among Turkish families living in the Netherlands indicated that sometimes sons and daughters of Turkish patients decided to move out in order to flee from the duty they saw as too heavy [80]. One reason for relatives’ exhaustion was the contrasting opinions of patients and relatives regarding the feasibility of family care [17, 81]. Other studies found that relatives felt that the illness imposed a heavy financial burden on the family, as the health-care insurance did not cover all the costs of family care [26, 60, 77].

Findings relating to perspectives regarding professional care

Twenty-five studies addressed the contribution of professionals in the care for incurably ill Turkish and Moroccan patients. Three topics were mentioned frequently: (1) a preference for hospital care, (2) barriers to professional care and (3) the quality of professional care.

A preference for hospital care

In Turkey it was found that 43% of the gynaecological cancer patients (in cases where cure was no longer an option) preferred to stay in the hospital, 41% preferred outpatient care and 16% wished to go home; the main reason for wanting to stay in hospital was the feeling of security [32]. Turkish professionals were more likely to want terminal patients to leave the hospital as they accepted that hospitals cannot cure these patients [28, 64]. Ersoy and Gundogmus found that “most GPs preferred to hospitalize the patient, even by using force if necessary, in order to keep the patient from harm”. Turkish physicians were more inclined to fulfil the wishes of the patients’ family than to respect the patients’ wishes [54]. In a study performed in the Netherlands, most Turkish and Moroccan patients preferred to die at home, but being in the hospital was preferred if they still hoped for a cure or wanted to relieve the family [26]. Buiting et al. found that immigrants were more likely to die in hospital than Dutch patients [35].

Barriers to the use of professional care

According to patients, relatives and professionals, the main reasons for immigrants’ limited use of professional home care, residential care for the elderly or hospice care were unfamiliarity with the available care facilities and language barriers [33, 45, 60, 77]. Also financial problems and traditional views on family duties sometimes formed barriers to using professional care [17, 23, 26, 80]. Relatives’ care preferences and feelings of shame were often a deciding factor in the limited use of professional care [17, 47, 80].

Perspectives on the quality of professional care

The quality of care was discussed mainly from the perspective of professionals. It was found that the use of hospital care in Turkey was hampered by limited communication between patient and relatives, and limited cooperation among professionals [64]. Another study reported that more than half of the nurses working in an oncology centre in Ankara had experienced inadequate pain management [67]. Furthermore, nurses and physicians working in oncology centres in Morocco felt embarrassed by the lack of resources and limited training in the treatment of cancer-related pain [63].

In the Netherlands, relatives of patients with a Turkish or Moroccan background often felt responsible for the care being given, making them very critical of the professionals’ activities [22, 60, 65]. Professionals in the Netherlands felt the insufficient quality of palliative care for immigrant patients was mainly due to communication problems [18, 23, 45, 60].

Findings relating to perspectives regarding end-of-life care and decision making

Thirty-five studies addressed the perspectives regarding end-of-life care or decisions at the end-of-life. Five topics were mentioned frequently: (1) hope and faith, (2) views regarding euthanasia, (3) withdrawing and withholding treatment, (4) artificial nutrition and continuing to offer food, and (5) involvement in decision-making.

Hope for cure and faith in Allah

Many studies revealed that Turkish and Moroccan patients often strive for maximum treatment right up to the end of life. For instance, 63% of the gynaecological cancer patients in the study by Beji et al. (2005) asked for life-sustaining treatments [32]. Patients only refused life-sustaining treatments in cases where the patient was suffering from poor family relationships, pain or depression. Errihani et al. (2008) found that patients with cancer who were not practicing Muslims (49%) often felt guilty, while active believers commonly accepted cancer as a divine test [51].

In the Netherlands, the keenness among Turkish and Moroccan patients to have life-sustaining treatments was confirmed in a study by De Graaff et al. [18]. Dutch physicians noted that immigrants were more likely than Dutch patients to be offered life-prolonging treatments (20% vs 12%), artificial respiration (38% vs 16%) and cardiovascular medication (30% vs 11%) [35]. Some families related their wish for life-prolonging treatments to their Muslim religion [18, 22, 59, 60]. Some relatives also mentioned the wish to let the patient die with a clear mind, enabling a good start in the hereafter [18].

Perspectives on euthanasia

In the Netherlands euthanasia is defined as being the termination of life by a doctor at the request of a patient [3]. This also includes physician-assisted suicide. Euthanasia is not taken to mean abandoning treatment if (further) treatment is pointless. In such cases it is considered part and parcel of normal medical practice that the doctor discontinues treatment and lets nature take its course. The same applies to administering large doses of opiates for pain relief whereby one side effect is that death occurs more quickly.

Several studies in Turkey addressed the concept of ‘euthanasia’, although what respondents meant by this concept varied. One study recorded that Turkish nurses and doctors did not have the same knowledge about the different forms of euthanasia (active euthanasia, passive euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide and involuntary euthanasia) [75]. They were most familiar with passive euthanasia (73.2% of doctors and 62.6% of nurses). In a study by Oz, most nurses and physicians (58%) defined it as “allowing death, leaving patients to die”, others (17%) defined it as “passive euthanasia, not active death determined by others”, or as “painless, peaceful death” (13%) [69].

Some Turkish studies suggest that professionals do sometimes get requests to perform euthanasia or “to make death easy”. The number of professionals that had been asked to do so varied (see Table 3), ranging from 8% of the professionals in the study by Turla et al. [76] to 34% of the oncologists in the study by Mayda et al. [62]. The different percentages may be related to the above-mentioned differences and/or a lack of clarity in definitions of euthanasia or “making death easy”. The responses to a patient’s request for euthanasia or “making death easy” also varied (see Table 3). Most professionals in Turkey were disapproving of any form of legalization of euthanasia. The reasons for objecting to legalization were fear of abuse, ethical principles, religious beliefs and personal values [62, 75, 76].

No Moroccan studies about views on euthanasia were found. But in the Netherlands, a study concluded that patients and families with a Dutch background were more likely to request euthanasia (25% and 18%) than migrants and their relatives (3% and 4%) [35].

Withdrawing or withholding life-prolonging treatments

One study found that older Turkish patients often opted for life-prolonging treatments; even when they longed to die, they accepted life-prolonging proposals from physicians as their relatives wanted them to live as long as possible [31]. Another study noted that 38% of the Turkish physicians had advised patients not to start life-prolonging therapy and 51% had withdrawn treatment [62]. Although withdrawing treatment was often felt to be reprehensible, professionals also admitted it to be part of their job. In one study, for example, 40% of the Turkish intensive-care nurses justified withdrawing treatment when there was no medical benefit [27], and another study [75] found that 40% of the intensive-care physicians had discontinued treatment in patients with an incurable disease on more than one occasion. Withdrawing treatment was more difficult than not initiating the treatment [40], and was often a matter for discussion. 84% of the Turkish physicians in the study of Ersoy and Gundogmus found withholding treatment acceptable if the patient wished for it, but only 13% would respect the patients’ wishes if relatives contested this [54]. Ilkilic described how Turkish parents living in Germany wished to continue mechanical respiration of their incurably ill child, referring to their religious duties, while the German physicians judged the situation to be medically hopeless [56].

Continuing to offer food and artificial nutrition

Several studies reported that Turkish patients often expect to be fed until the very end. In one study 75% of health staff disagreed with the statement that, nutrition should be stopped if a patient wants euthanasia [58], while 68% of the nurses in another study agreed that artificial nutrition should always be continued [27].

No Moroccan studies were found on this topic, but in the Netherlands it was reported that Turkish and Moroccan immigrant families preferred the feeding of their terminally ill relatives to continue [18]. Besides, it was found that terminally ill immigrants in the Netherlands were more likely to be given artificial nutrition and hydration than comparable native Dutch patients [35].

Involvement in end-of-life decisions

In Turkey, many cancer patients wanted to be involved in decisions about treatments (79% of the sample in one study, for example [49]), but use of written advanced directives was low and do-not-resuscitate orders were often only given verbally [57, 79]. In practice, relatives were often the ones making the decision in end-of life care. In one study, 54% of the Turkish oncologists said patients should decide about euthanasia and 42% said families and doctors should decide jointly [62]. The strong involvement of relatives in decision making is also described by Iyilikçi et al. [57]. However, some studies also pointed to preferences for taking decisions jointly: Iyilikçi et al., for example, concluded that most anaesthesiologists in Turkey wanted decision by consensus [57]. Moreover, Turla et al. reported that 63% of the professional care providers wished that “both the physician and the family” could decide [76]. Yet other authors remarked that decisions were often still the domain of physicians [31, 49, 71, 74].

This topic was not addressed in studies performed in Morocco, but Dutch research indicated that Turkish and Moroccan relatives sometimes did not want any medical end-of-life decisions to be taken as the end of life ought to be in the hands of Allah [22]. In other studies relatives declared that they should be the main party in the decision-making and not the patient, as the latter deserved rest and had to remain hopeful until the end [18, 23]. However, this contrasted with the dominant view of Dutch professionals that decision making should always reflect the preferences of the individual patient.

Findings relating to communication

Thirty-seven studies addressed the communication between Turkish and Moroccan patients and relatives and their care providers in end-of-life care. Four topics were mentioned frequently: (1) communication about diagnosis and prognosis, (2) communication about pain, sorrow and mental problems, (3) language barriers and (4) communication patterns within the family.

Communication about diagnosis and prognosis

Most studies on communication about diagnosis and prognosis were performed in Turkey. In this country the percentages of patients unaware of their diagnosis varied (see Table 4), ranging from 16% [48] to 63% [37]. The wish to be informed varied from 66% of the patients with diverse diagnoses [48] to 85% of patients diagnosed with cancer [31, 49]. Relatives may form barriers to informing patients about a bad diagnosis or prognosis. In one study, it was found that many relatives (66%) did not want patients to be informed because they would be upset or would not want to know it [71]. Another study found that 39% of the relatives adhered to this opinion, 48% felt that patients should be informed, and 13% were hesitant [68]. The differences between the findings might be due to the differences in the formulation of the questions.

The likelihood of Turkish physicians informing patients increased with an increase in the patient’s socio-economic status and educational level [37], and also depended on the type of illness and on relatives’ preferences [22, 54]. Although 93% of the physicians in the study by Pelin and Arda [74] thought that patients should be informed, 30% chose to inform relatives. While 67% of the physicians in another study would tell the truth to the patient, 8% preferred to inform relatives and 12% would ask relatives for their consent before talking to the patient [54]. However, 68% of the physicians in a third study said they would tell the patient the diagnosis first before informing their relatives [31]. Professionals’ attitudes were influenced by their skill in bringing bad news and by the stage of the disease. Trained and more experienced physicians were more likely to inform the patient [72, 74]. Furthermore, 76% of nurses would tell the truth to a breast-cancer patient asking for a diagnosis [53], while 96% would not inform a patient in the terminal phase [67].

In Morocco, 33% of cancer patients did not know their diagnosis, while relatives were informed in 89% of cases [52]. In the Netherlands, some Turkish and Moroccan patients were not informed [17, 33, 45, 59]. Elderly patients would not talk about life-threatening illnesses [26], whereas younger patients often preferred to be informed but would not inform all their relatives [59]. The arguments used were that telling the truth would hasten a patients’ death and that information might stir gossiping in the community [56, 59]. In addition, Turkish and Moroccan relatives disliked the direct way Dutch care providers informed patients [18, 23, 26]. The influence of relatives in communication is amplified by their role as interpreters [18, 33, 59].

Communication about pain, sorrow and mental problems

Several studies noted that communication with a patient at the end of life is often problematic. For example, one study found that Turkish patients often did not want to talk about pain as they feared becoming dependent on analgesics and did not want to upset their relatives [30]. Atesci et al. found more psychiatric disorders among patients aware of their diagnosis than among patients who were not informed, but this might be related to inadequate information so the authors concluded that physicians should teach patients to cope with the information [29]. Turkish nurses felt embarrassed because they could not express their feelings of empathy for dying people [64].

McCarthy et al. reported that Moroccan physicians and nurses did not have the means to detect or assess pain as their patients did not indicate pain, either physically or verbally [63]. Studies in the Netherlands report that, according to patients and relatives, immigrant patients would often not talk about psychological problems, depression or dementia [23, 66, 77].

Language barriers

In a Moroccan study it was noted that 25% of the patients spoke only Berber. Their insufficient knowledge of Arabic caused enormous difficulties in communication between patients and professionals [50].

According to patients, relatives and care providers in the Netherlands, language barriers were often tackled with the help of relatives and bilingual interpreters or other intermediary professionals [17, 18, 60]. Many elderly Turkish patients living in the Netherlands said they wanted Turkish-speaking staff [33]. This was sometimes arranged [77]. But involving staff of Turkish or Moroccan origin could also amplify undesirable social control within the community [26, 59]. In another immigrant country, namely Germany, it was noted that language barriers impeded physicians in taking joint decisions with Turkish patients - they could not understand the discussions between patients and interfering relatives [56].

Communication within the family and within the community

Many studies suggested that communication problems in palliative care were sometimes related to the social patterns within the family. For example, one study concluded that according to patients, the dominance of families in patient support often resulted in low disclosure rates in Turkey [34]. In a study performed among Turkish and Moroccan health advisors in the Netherlands, it was found that Turkish and Moroccan immigrant families seldom talk about illness and the sorrow it causes because they wanted to avoid gossiping in the community [59]. According to elderly immigrants, immigrant families were facing a dilemma: the ideal of children taking care of parents prevented them from discussing care needs openly and from looking for other sources of care [23]. The explanations given for limited communication within the family were immigrants’ limited experience with dying, as the previous generation was cared for in their country of origin [18], a lack of knowledge about the facilities in the host country [26] and religious traditions: the obligation to provide care, and pressure from the community, be it Muslims [17, 80] or Christians [55].

Discussion

This systematic literature study describes the care experiences and care perceptions of incurably ill Turkish and Moroccan patients, their relatives and care professionals, and their communication with each other.

The extensive searches resulted in 64 relevant references dealing with 57 studies. Eighteen of the 57 studies concerned family care. These studies showed that relatives considered family care as a duty, although the care burden was often too high for the female relatives in particular. This conclusion was mainly based on studies of Turkish and Moroccan immigrant families living in the Netherlands as family care has never been a central issue in the studies in the countries of origin (Turkey and Morocco).

Twenty-five studies addressed perceptions regarding professional care. A lot of Turkish and Moroccan incurably ill patients and their relatives preferred hospitalization, which was related to their search for security and a cure right up to the end. In addition, the limited use of professional home care and residential elderly care was also due to financial problems, preferences for family care, communication problems and the insufficient quality of care. However, it should be noted that the preferences for certain kinds of care will depend on the availability of alternatives. This could explain why preferences for hospital care were addressed mainly in Turkish studies, while the thresholds to using professional home care, residential care for the elderly and hospice care were mainly studied among immigrants in the Netherlands.

On the basis of 35 studies addressing the perspectives concerning end-of-life care and decision making, we can conclude that patients and family often wanted life-prolonging treatments until the very end. Decisions to withdraw or withhold treatments were often contested by relatives and not openly discussed with the patient. Hope for a cure and the desire for life-prolonging treatments were related to faith in Allah. Patients’ and relatives’ focus on life prolongation might be a reason for the fact that perceptions regarding euthanasia and views on withdrawing or withholding treatments were only investigated in studies among professionals. These studies – mainly performed in Turkey - showed that, in general, withdrawing treatment and euthanasia were disapproved of. But the findings of these studies were not congruent in all regards: some studies emphasized a preference for shared decision-making, while other studies noted that decisions were still often made by physicians or relatives, with the patients’ opinion not being taken into account.

Thirty-seven studies addressed communication. Incurably ill patients with a Turkish or Moroccan background were not always informed about their diagnosis although professionals frequently held the opinion that patients should be informed. Relatives often prevented disclosure as they felt this might upset their patient, even when patients wished to know the truth. Additionally, communication about pain and psychological symptoms was often problematic because patients were reluctant to talk, fearing the use of analgesics and wanting to avoid upsetting their relatives. Language barriers and the dominance of the family reinforced the often complex communication patterns. Communication was often hampered by language barriers (in the Netherlands, but also in Morocco) or the relatives’ dominant role.

A limitation of this review is that we could not synthesize the data of underlying studies in all regards because of the variety of instruments and research questions. Findings were frequently not in agreement, even on topics that have been studied rather intensively (such as informingpatients about the diagnosis and prognosis), due to diverging research questions, designs and instruments.

Account must also be taken of the fact that the representativeness of the results is sometimes open to discussion, as the response rates in the quantitative studies were often unknown or low, and the qualitative studies had small samples.

Another limitation is that the majority of the studies included in the review concerned professionals in Turkey or immigrants’ relatives in the Netherlands. In general the patient perspective was under-represented, and there were only a limited number of studies in Morocco, hampering comparisons between Turkish and Moroccan subjects. In addition, we cannot draw conclusions on the basis of this review as to whether the specific experiences and perceptions of Turkish and Moroccan immigrants are rooted in either their past in the country of origin or in their present situation as immigrants in a foreign country. Time may be an important factor, both for Turkish, Moroccan and Dutch professionals and for Turkish and Moroccan patients and their relatives. As VPTZ [26] indicated, a culturally sensitive approach may lead to an acceptance of the do-not-tell wishes of some elderly first-generation immigrants, but will not suit the information needs of second-generation immigrants.

This review confirms the view that palliative care should take account of the specific cultural characteristics of patients and relatives. In the Introduction section we referred to studies indicating that poverty, family systems, religious customs and traditional care influenced the care perceptions of patients in non-Western low-resource countries. This corresponds with our findings on incurably ill patients with a Turkish and Moroccan background. In addition, we referred to studies showing that palliative care for immigrants in Western countries is often hindered by language barriers and health illiteracy, resulting in an important role for interpreting relatives. Comparable communication features were found in this review dealing specifically with people with a Turkish or Moroccan background.

A question that subsequently arises is whether our findings on Turkish and Moroccan patients and families can also be applied to other immigrant groups in the Netherlands, such as Moluccan, Chinese, Surinamese and Antillean immigrants, and refugees from various countries. No unequivocal conclusions can be drawn on the basis of this review as the immigrant groups mentioned differ from Turkish and Moroccan immigrants in terms of of the countries they come from, when and why they immigrated to the Netherlands, their reception in the Netherlands and Dutch language skills. Future research on care beliefs, needs and communication processes in the palliative care phase for other immigrant groups in the Netherlands could bolster and extend the current insights.

Conclusions

This systematic literature study confirms the findings of our earlier empirical studies, showing that family care for incurably ill patients is considered a duty, even when this care becomes a severe burden for the central female family caregiver in particular. Hospitalization is preferred by a substantial proportion of patients and relatives, since they often strive for cure right up to the end and focus strongly on life-prolonging treatments. Relatives often prevent disclosure as they feel this might upset their patient, even when patients wish to know the truth. Medical end-of life decisions, such as withdrawing and withholding treatment, are seldom discussed with the patient. In addition, communication about pain or mental issues is limited. Language barriers and the dominance of the family may amplify communication problems. Apart from these concrete findings our review revealed that the perspectives on care and communication involving incurably ill Turkish and Moroccan patients not only reflect their cultural background but also their social situation. This dual focus enables palliative care policy makers and practitioners to take account of the social and economic circumstances of each family, the mental and physical barriers preventing them from engaging professional care, the religious and legal considerations influencing their decision making and their communication capacities.

What is already known about the topic?

The international literature has shown that palliative care for non-Western patients can be problematic because of inadequate pain relief and medication, as wells as family systems and religious practices. In addition, palliative care for ethnic minorities in Western countries can be limited by languages barriers, ignorance about specified facilities, discrimination and criticism from their community.

What the paper adds

Our review looking at Turkish and Moroccan patients demonstrates that the ‘family’ factor is crucial. Palliative care for Turkish and Moroccan patients has to take account of the fact that family care is dominant and that the desire for a cure leads to a preference for hospital care, even when cure is no longer an option. Efforts to inform incurably ill patients about their diagnosis and prognosis, and share decisions regarding medical end-of life decisions are often contested by relatives, who want to protect the patients and keep hope alive. Even when patients want to know the truth, they are often protected by their relatives.

References

Centeno C, Clark D, Lynch T, Racafort J, Praill D, De LIma L, et al: Facts and indicators on palliative care development in 52 countries of the WHO European region: results of an EAPC task force. Palliat Med. 2007, 21: 463-471. 10.1177/0269216307081942.

Francke AL, Kerkstra A: Palliative care services in the Netherlands. Patient Educ Couns. 2000, 41: 23-33. 10.1016/S0738-3991(00)00112-9.

Francke AL: Palliative care for terminally ill patients in the Netherlands. Dutch Government Policy. 2003, Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, The Hague

Selman LE, Beattie JM, Murtagh FE, Higginson IJ: Palliative care: Based on neither diagnosis nor prognosis, but patient and family need. Commentary on Chatoo and Atkin. Soc Sci Med. 2009, 69: 154-157. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.024.

WHO: Palliative care. 2011, Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/en/ (accessed: 2011)

Bingley A, Clark D: A comparative review of palliative care development in six countries represented by the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC). J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009, 37: 287-296. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.02.014.

Chaturvedi SK: Ethical dilemmas in palliative care in traditional developing societies, with special reference to the Indian setting. J Med Ethics. 2008, 34: 611-615. 10.1136/jme.2006.018887.

Macpherson CC: Healthcare development requires stakeholder consultation: palliative care in the Caribbean. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2006, 15: 248-255.

McGrath P, Vun M, McLeod L: Needs and experiences of non-English-speaking hospice patients and families in an English-speaking country. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2001, 18: 305-312. 10.1177/104990910101800505.

Kreps GL, Sparks L: Meeting the health literacy needs of immigrant populations. Patient Educ Couns. 2008, 71: 328-332. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.001.

Gunaratnam Y: Intercultural palliative care: do we need cultural competence?. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2007, 13: 470-477.

Smith AK, Sudore RL, Perez-Stable EJ: Palliative care for Latino patients and their families: whenever we prayed, she wept. JAMA. 2009, 301: 1047-1057. 10.1001/jama.2009.308.

Gunaratnam Y: Eating into multiculturalism: hospice staff and service users talk food, 'race', ethnicity, culture and identity. Crit Soc Pol. 2001, 21: 287-310. 10.1177/026101830102100301.

Gunaratnam Y: From competence to vulnerability: care, ethics, and elders from racialized minorities. Mortality. 2008, 13: 24-41. 10.1080/13576270701782969.

Owens A, Randhawa G: 'It's different from my culture; they're very different': Providing community-based, 'culturally competent' palliative care for South Asian people in the UK. Health Soc Care Community. 2004, 12: 414-421. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00511.x.

Worth A, Irshad T, Bhopal R, Brown D, Lawton J, Grant E, et al: Vulnerability and access to care for South Asian Sikh and Muslim patients with life limiting illness in Scotland: prospective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ. 2009, 338: b183-10.1136/bmj.b183.

de Graaff F, Francke AL: Home care for terminally ill Turks and Moroccans and their families in the Netherlands: carers' experiences and factors influencing ease of access and use of services. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003, 40: 797-805. 10.1016/S0020-7489(03)00078-6.

de Graaff F, Francke AL, Van den Muijsenbergh ME, van der Geest S: Communicatie en besluitvorming in de palliatieve zorg voor Turkse en Marokkaanse patiënten met kanker [Communication and decision making in the palliative care for Turkish and Moroccan patients withn cancer]. 2010, UvA, Spinhuis, Amsterdam

CBS: Jaarrapport Integratie 2010 [2010 Annual Report on Integration]. 2010, Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, The Hague/Heerlen

de Graaff F, Francke AL: Zorg voor Turkse en Marokkaanse ouderen in Nederland [Care for elderly Turkish and Moroccan immigrants in the Netherlands]. Verpleegkunde. 2002, 17: 131-139.

Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J: Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res. 2002, 12: 1284-1299. 10.1177/1049732302238251.

ACTIZ: Interculturele palliatieve zorg: Vraaggericht en individueel [Intercultural palliative care: responsive to requirements and individualized]. 2009, Actiz, Utrecht

NOOM: Bagaimana - Hoe gaat het? Een verkenning van kwetsbaarheid bij oudere migranten [Bagaimana- How are you? An exploratory study of the vulnerability of elderly immigrants]. 2009, NOOM, Utrecht

Signaleringscommissie Kanker van KWF Kankerbestrijding: Allochtonen en kanker; Sociaal-culturele en epidemiologische aspecten [immigrants and cancer; socio-cultural and epidemiological aspects. Report by the Dutch Cancer Society's Signalling Committee]. 2006, KWF, Amsterdam

VPTZ: "Gaat u het gesprek aan?" - Goede zorg voor stervenden van allochtone afkomst. Publieksversie eind-rapportage [Does this conversation concern you?" Good quality care for dying immigrants. Version of final report for the general public]. 2008, VPTZ, Bunnik

VPTZ: "Gaat u het gesprek aan?" Eind-rapportage ["Does this conversation concern you?"]. 2008, VPTZ, Bunnik

Akpinar A, Senses MO, Aydin ER: Attitudes to end-of-life decisions in paediatric intensive care. Nurs Ethics. 2009, 16: 83-92. 10.1177/0969733008097994.

Aksoy S: End-of-life decision making in Turkey. End-of-life decision making: a cross-national study. Edited by: Blank R, Merrick J. 2005, MIT Press, Cambridge

Atesci FC, Baltalarli B, Oguzhanoglu NK, Karadag F, Ozdel O, Karagoz N: Psychiatric morbidity among cancer patients and awareness of illness. Support Care Canc. 2004, 12: 161-167. 10.1007/s00520-003-0585-y.

Bagcivan G, Tosun N, Komurcu S, Akbayrak N, Ozet A: Analysis of patient-related barriers in cancer pain management in Turkish patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009, 38: 727-737. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.03.004.

Balseven Odabasi A, Ornek Buken N: Informed consent and ethical decision making in the end of life: Hacettepe example. Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2009, 29: 1041-1054.

Beji NK, Reis N, Bag B: Views of patients with gynecologic cancer about the end of life. Support Care Canc. 2005, 13: 658-662. 10.1007/s00520-004-0747-6.

Betke P: Divers sterven…: een explorerend onderzoek naar palliatieve zorg in een verpleeghuis aan Turkse ouderen [Diveristy in dying…: an exploratory study of palliative care for elderly Turkish immigrants in a nursing home]. 2005, Erasmus Universiteit, Rotterdam

Bozcuk H, Erdogan V, Eken C, Ciplak E, Samur M, Ozdogan M, et al: Does awareness of diagnosis make any difference to quality of life? Determinants of emotional functioning in a group of cancer patients in Turkey. Support Care Canc. 2002, 10: 51-57. 10.1007/s005200100308.

Buiting H, Rietjens JA, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Maas PJ, van Delden JJ, Van Der Heide A: A comparison of physicians' end-of-life decision making for non-western migrants and Dutch natives in the Netherlands. Eur J Publ Health. 2008, 18: 681-687. 10.1093/eurpub/ckn084.

Buiting H, Rietjens J, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, van der Maas P, van Delden J, Van Der Heide A: Medische besluitvorming in de laatste levensfase: Een vergelijking tussen niet-westerse migranten en autochtonen in Nederland [Medical decision making in the final phase of life: a comparison between non-Western immigrants and ethnic Dutch in the Netherlands]. 2009, Tijdschrift voor Palliatieve Zorg, Nederlands, 9.

Buken ND: Truth telling information and communication with cancer patients in Turkey. J Int Soc Hist Islamic Med. 2003, 2: 31-37.

Celik S, Gurkan S, Atilgan Y: A brief report of research: care activities for deceased patients of intensive care nurses at a private hospital in Istanbul, Turkey. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2009, 28: 232-236. 10.1097/DCC.0b013e3181ac4774.

Cetingoz R, Kentli S, Uruk O, Demirtas E, Eyiler F, Kinay M: Turkish people's knowledge of cancer and attitudes toward prevention and treatment. J Canc Educ. 2002, 17: 1755-1758.

Cobanoglu N, Algier L: A qualitative analysis of ethical problems experienced by physicians and nurses in intensive care units in Turkey. Nurs Ethics. 2004, 11: 444-458. 10.1191/0969733004ne723oa.

Cohen J, Marcoux I, Bilsen J, Deboosere P, van der Wal G, Deliens L: European public acceptance of euthanasia: socio-demographic and cultural factors associated with the acceptance of euthanasia in 33 European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 63: 743-756. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.026.

de Graaff F: Tips voor terminale thuiszorg voor Turkse en Marokkaanse ouderen [Tips for terminal home care for elderly Turkish and Moroccan immigrants]. 2002, NIVEL, Utrecht

de Graaff F, Francke AL: Terminale thuiszorg voor Turkse en Marokkaanse ouderen [Terminal home care for elderly Turkish and Moroccan immigrants]. TSG. 2003, 81: 24.

de Graaff F, van Hasselt T, Francke AL: Thuiszorg voor terminale Turkse en Marokkaanse patiënten: ervaringen en opvattingen van naasten en professionals [Home care for terminally ill Turkish and Moroccan patients: the experiences and views of family and professionals]. 2005, NIVEL, Utrecht

de Graaff F, Francke AL: Barriers to home care for terminally ill Turkish and Moroccan migrants, perceived by GPs and nurses: a survey. BMC Palliative Care. 2009, 8: 3-10.1186/1472-684X-8-3.

de Graaff F, Francke AL, Van den Muijsenbergh ME, Van der Geest S: 'Palliative care': a contradiction in terms? A qualitative study among cancer patients with a Turkish or Moroccan background, their relatives and care providers. BMC Palliat Care. 2010, 9: 19-10.1186/1472-684X-9-19.

de Meyere V: Verwerking van borstkanker bij Turkse vrouwen. Op zoek naar een cultureel aangepaste ondersteuning [How Turkish women deal with breast cancer. A search for culturally adapted support]. Cultuur Migratie Gezondheid. 2004, 1: 2-13.

Demirsoy N, Elcioglu O, Yildiz Z: Telling the truth: Turkish patients' and nurses' views. Nurs Sci Q. 2008, 21: 75-79. 10.1177/0894318407311150.

Erer S, Atici E, Erdemir AD: The views of cancer patients on patient rights in the context of information and autonomy. J Med Ethics. 2008, 34: 384-388. 10.1136/jme.2007.020750.

Errihani H, Mrabti H, Boutayeb S, Ichou M, El Mesbahi O, El Ghissasi I, et al: Psychosocial profile of Moroccan breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2006, 17: ix280.

Errihani H, Mrabti H, Boutayeb S, El Ghissasi I, El Mesbahi O, Hammoudi M, et al: Impact of cancer on Moslem patients in Morocco. Psychooncology. 2008, 17: 98-100. 10.1002/pon.1200.

Errihani H, Mrabti H, Sbitti Y, El Ghissasi I, Afqir S, Boutayeb S, et al: Caractéristiques psychosociales des patients cancéreux marocains: étude de 1 000 cas recrutés à l'Institut national d'oncologie de Rabat [Psycho-social and religious impact of cancer diagnosis on Moroccan patients: experience from the national oncology center of Rabat]. Bull Canc (Paris). 2005, 97: 461-468.

Ersoy N, Goz F: The ethical sensitivity of nurses in Turkey. Nurs Ethics. 2001, 8: 299-312.

Ersoy N, Gundogmus UN: A study of the ethical sensitivity of physicians in Turkey. Nurs Ethics. 2003, 10: 472-484. 10.1191/0969733003ne6290a.

Groen van de Ven L, Smits C: Aandacht, acceptatie en begrip. Mantelzorg aan ouderen in de Suryoye gemeenschap [Attention, acceptance and understanding. Care for the elderly by friends and family in the Suryoye community]. Cultuur Migratie en Gezondheid. 2009, 6: 198-208.

Ilkilic I: Kulturelle Aspekte bei ethischen Entscheidungen am Lebensende und interkulturelle Kompetenz [Cultural aspects of ethical decisions at the end of life and cultural competence]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2008, 51: 857-864. 10.1007/s00103-008-0606-6.

Iyilikci L, Erbayraktar S, Gokmen N, Ellidokuz H, Kara HC, Gunerli A: Practices of anaesthesiologists with regard to withholding and withdrawal of life support from the critically ill in Turkey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004, 48: 457-462. 10.1046/j.1399-6576.2003.00306.x.

Karadeniz G, Yanikkerem E, Pirincci E, Erdem R, Esen A, Kitapcioglu G: Turkish health professional's attitude toward euthanasia. Omega J Death Dying. 2008, 57: 93-112. 10.2190/OM.57.1.e.

Koppenol M, Francke AL, Vlems F, Nijhuis H: Allochtonen en kanker. enkele onderzoeksbevindingen rond betekenisverlening, communicatie en zorg [Immigrants and cancer. Some research findings on giving meaning, communication and care]. Cultuur Migratie Gezondheid. 2006, 3: 212-222.

Korstanje M: "Ik had eigenlijk heel veel willen vragen". Mantelzorgers van allochtone patienten in ziekenhuizen ["I really had a lot of questions". Non-professional carers of immigrant patients in hospital]. Cultuur Migratie Gezondheid. 2008, 5: 24-31.

Kumas G, Oztunc G, Nazan AZ: Intensive care unit nurses' opinions about euthanasia. Nurs Ethics. 2007, 14: 637-650. 10.1177/0969733007075889.

Mayda AS, Ozkara E, Corapcioglu F: Attitudes of oncologists toward euthanasia in Turkey. Palliat Support Care. 2005, 3: 221-225.

McCarthy P: Managing children's cancer pain in Morocco. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004, 36: 11-15. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04005.x.

Meric M, Sayligil Elcioglu O: The observations and problems of the nurses providing care for the patients in terminal periods. SENDROM. 2004, 16: 109-115.

Meulenkamp TM, van Beek APA, Gerritsen DL, de Graaff F, Francke AL: Kwaliteit van leven bij migranten in de ouderenzorg. Een onderzoek onder Turkse, Marokkaanse, Surinaamse, Antilliaanse/Arubaanse en Chinese ouderen [Quality of life of immigrants in the care system for the elderly. A study of elderly Turkish, Moroccan, Surinam, Antilles/Aruban and Chinese immigrants]. 2010, NIVEL, Utrecht

Mostafa S: Allochtone vrouwen met borstkanker [ Ethnic minority women with breast cancer]. 2009, Radboud Universiteit, afdeling eerstelijnsgeneeskunde, Nijmegen

Oflaz F, Arslan F, Uzun S, Ustunsoz A, Yilmazkol E, Unlu E: A survey of emotional difficulties of nurses who care for oncology patients. Psychol Rep. 2010, 106: 119-130. 10.2466/pr0.106.1.119-130.

Oksuzoglu B, Abali H, Bakar M, Yildirim N, Zengin N: Disclosure of cancer diagnosis to patients and their relatives in Turkey: views of accompanying persons and influential factors in reaching those views. Tumori. 2006, 92: 62-66.

Oz F: Nurses' and physicians' views about euthanasia. Clin Excell Nurse Pract. 2001, 5: 222-231. 10.1054/xc.2001.25009.

Ozcakir A, Uncu Y, Sadikoglu G, Ercan I, Bilgel N: Students' views about doctor-patient communication, chronic diseases and death. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2008, 21: 149.

Ozdogan M, Samur M, Bozcuk HS, Coban E, Artac M, Savas B, et al: "Do not tell": What factors affect relatives' attitudes to honest disclosure of diagnosis to cancer patients?. Support Care Canc. 2004, 12: 497-502.

Ozdogan M, Samur M, Artac M, Yildiz M, Savas B, Bozcuk HS: Factors related to truth-telling practice of physicians treating patients with cancer in Turkey. J Palliat Med. 2006, 9: 1114-1119. 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1114.

Ozkara E, Hanci H, Civaner M, Yorulmaz C, Karagoz M, Mayda AS, et al: Turkey's physicians' attitudes toward euthanasia: a brief research report. Omega J Death Dying. 2004, 49: 109-115. 10.2190/E88C-UXA5-TL9T-RVLK.

Pelin SS, Arda B: Physicians' attitudes towards medical ethics issues in Turkey. J Int Bioethique. 2000, 11: 57-67.

Tepehan S, Ozkara E, Yavuz MF: Attitudes to euthanasia in ICUs and other hospital departments. Nurs Ethics. 2009, 16: 319-327. 10.1177/0969733009102693.

Turla A, Ozkara E, Ozkanli C, Alkan N: Health professionals' attitude toward euthanasia: a cross-sectional study from Turkey. Omega J Death Dying. 2006, 54: 135-145.

van den Bosch AF: Baklava & zoete praatjes; ouder worden in multicultureel Nederland. Een onderzoeksrapport met een positief verhaal over de gezondheidssituatie, het zorggebruik en het vertrouwen in de arts van oudere Turkse Nederlanders. 2010, Universiteit Twente, Enschede

van Wijmen MP, Rurup ML, Pasman HR, Kaspers PJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD: Advance directives in the Netherlands: an empirical contribution to the exploration of a cross-cultural perspective on advance directives. Bioethics. 2010, 24: 118-126. 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2009.01788.x.

Yaguchi A, Truog RD, Curtis JR, Luce JM, Levy MM, Melot C, et al: International differences in end-of-life attitudes in the intensive care unit: results of a survey. Arch Intern Med. 2005, 165: 1970-1975. 10.1001/archinte.165.17.1970.

Yerden I: Zorgen over zorg. Traditie, verwantschapsrelaties, migratie en verzorging van Turkse ouderen in Nederland [Concerns about care. Tradition, relationships, migration and the care of elderly Turkish migrants in the Netherlands]. 2000, Het Spinhuis, Amsterdam

Yerden I: Blijf je in de buurt? Zorg bij zorgafhankelijke Turkse ouderen [Can you stay? Care for care-dependant elderly Turkish immigrants]. Cultuur Migratie Gezondheid. 2004, 1: 28-37.

Yerden I, van Koutrike H: Voor je familie zorgen? Dat is gewoon zo. Mantelzorg bij allochtonen. Mantelzorg bij Antillianen, Surinamers, Marokkanen en Turken in Nederland [Caring for your family? That's just somethinig you do. Care for ethnic minority patients by family and friends. Care for immigrants in the Netherlands from the Antilles, Surinam, Morocco and Turkey]. 2007, Primo, Purmerend

Yildirim Y, Sertoz OO, Uyar M, Fadiloglu C, Uslu R: Hopelessness in Turkish cancer inpatients: the relation of hopelessness with psychological and disease-related outcomes. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009, 13: 81-86. 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.01.001.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-684X/11/17/prepub

Acknowledgements

The research presented was financially supported by ZonMw, The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FMG and ALF designed the study; FMG and PM performed all phases of the systematic review; WD and ALF were involved in the methodological assessment; FMG wrote initial draft of this paper and PM, WD and ALF gave comments on all following versions and the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

de Graaff, F.M., Mistiaen, P., Devillé, W.L. et al. Perspectives on care and communication involving incurably ill Turkish and Moroccan patients, relatives and professionals: a systematic literature review. BMC Palliat Care 11, 17 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-11-17

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-11-17