Abstract

Background

Worldwide, many patients with cancer, are infrequently referred to palliative care or are referred late. Oncologists and haematologists may act as gatekeepers, and their views may facilitate or hinder referrals to palliative care. This review aimed to identify, explore and synthesise their views on referrals systematically.

Methods

Databases of MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science and Cochrane were searched for articles from 01/01/1990 to 31/12/2019. All studies were scored for their methodological rigour using Hawker’s tool. Findings were synthesised using Popay’s narrative synthesis method and interpreted using a critical realist lens and social exchange theory.

Results

Out of 9336 initial database citations, 23 studies were included for synthesis. Five themes were developed during synthesis.

1. Presuppositions of oncologists and haematologists about palliative care referral: Role conflict, abandonment, rupture of therapeutic alliance and loss of hope were some of the presuppositions that hindered palliative care referral. Negative emotions and perception of self-efficacy to manage palliative care need also hindered referral.

2. Power relationships and trust issues: Oncologists and haematologists preferred to gatekeep the referral process and wished to control and coordinate the care process. They had diminished trust in the competency of palliative care providers.

3. Making a palliative care referral: A daunting task: The stigma associated with palliative care, navigating illness and treatment associated factors, addressing patient and family attitudes, and overcoming organisational challenges made referral a daunting task. Lack of referral criteria and limited palliative care resources made the referral process challenging.

4. Cost-benefit of palliative care referral: Pain and symptom management and psychosocial support were the perceived benefits, whereas inconsistencies in communication and curtailment of care were some of the costs associated with palliative care referral.

5. Strategies to facilitate palliative care referral: Developing an integrated model of care, renaming and augmenting palliative care resources were some of the strategies that could facilitate a referral.

Conclusion

Presuppositions, power relationships, trust issues and the challenges associated with the task of referrals hindered palliative care referral. Oncologists and haematologists appraised the cost-benefit of making a palliative care referral. They felt that an integrated model of care, changing the name of palliative care and augmenting palliative care resources might facilitate a referral.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide, the majority of patients with cancer present in late stages of illness and need palliative care [1]. However, they are infrequently referred to palliative care or are referred late [2,3,4,5]. Early palliative care referral is associated with improved quality of life, symptom control, treatment decision making, advance care planning, end of life care and reduced costs [6,7,8]. In a cancer care setting, oncologists and haematologists may act as gatekeepers, and their views about palliative care referral may facilitate or hinder referral to palliative care [9, 10]. This research aimed to explore the views of oncologists and haematologists on specialist palliative care referral.

A scoping review of the multidisciplinary database Scopus [11], identified previous systematic reviews on palliative care referral. These reviews looked at barriers to accessing palliative care [12], referral patterns [13], referral criteria [14], and appropriateness of referral [15]. Other related systematic reviews looked at interventions to improve palliative care referral [16], integration of oncology and palliative care [17], the effect of age of the patient on palliative care referral [18], and collaboration between generalist and specialist palliative care teams [19]. Although there are studies about the views of oncologists and haematologists on palliative care referral, these studies have not been reviewed systematically necessitating this systematic review.

Methods

This research aimed to systematically identify, explore and synthesise the views of oncologists and haematologists on specialist palliative care referral. We conducted this systematic review with a review question as “What are the views of oncologists and haematologists on palliative care referral”? The review question was formulated using Population, Phenomenon of Interest and Context (PICo) framework [20]. The population studied were oncologists and haematologists; the phenomenon of interest was views on specialist palliative care referral, and the context was the cancer care setting.

The results of the scoping search showed that the typology of evidence informing this review is a heterogeneous mixture of surveys, qualitative studies, and mixed-method studies. Popay’s narrative synthesis method was chosen as the review approach as it is appropriate for synthesising textual data from surveys and qualitative studies into themes [21]. Moreover, it facilitates using a theoretical framework for interpreting study findings [21]. The literature was reviewed using a critical realist lens [22], and the findings were interpreted using social exchange theory [23]. Critical realist approach involves documenting the empirically known phenomenon of referral and going beyond the empiric observations to explain the actual events and generative mechanisms [24]. Social exchange theory is the theorisation of the social behaviour of exchange where people are motivated to engage in an exchange where they may gain or forfeit something of value [23].

The systematic review protocol was registered with the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. The PROSPERO registration number was CRD42018091481.

Search strategy

The review question was divided into search concepts, and a scoping search helped to identify the key search terms relevant to each concept of the review question. The scoping search also helped to identify three index papers to test the sensitivity of the search [25,26,27]. The index papers facilitated the expansion of the search terms to find free-text and thesaurus terms related to the scope of the review [28]. Four subject-specific databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and EMBASE) were searched by combining free-text and the thesaurus terms specific to the database using the Boolean operators [29]. Three multidisciplinary databases (Scopus, Web of Science and Cochrane database) were searched using free-text terms. Additional file 1 provides information about the thesaurus and free text terms used in this review.

Studies published in English involving human subjects from 01/01/1990 to 31/12/2019 was accessed. The article search was limited from 1990 onwards as the first published literature on palliative care in the MEDLINE dated back to 1993 [30]. Additional file 2 provides the list of eleven journals hand searched for additional citations. They were chosen based on the scoping review. The bibliographies of the full-text articles included in the review were checked to make sure that no relevant studies were missing [31]. The citations of the included publications were searched using Google Scholar and Web of Science to identify more articles pertaining to the review. The articles identified through citation searching were checked for their citations until the search led to no additional relevant articles [32].

Study eligibility and scoring for methodological rigour

The selection criteria of the studies included in the review are listed in Table 1. All studies were scored for their methodological rigour using Hawker’s tool [33]. Additional file 3 provides information about Hawker’s tool [33]. Hawker’s tool allows methodological scoring of a mixed typology of studies and a growing number of palliative care systematic reviews have used this tool [12, 19, 34]. Scoring is based on the nine criteria set by the Hawker provided in Additional file 3. Each criteria is assigned a score between 1 to 4 (1 = very poor and 4 = good), and 9 is the minimum score, and 36 is the maximum score [33]. Only those studies scoring 19 and above were included in the review. Although it has not provided a cut-off score for inclusion, previous palliative care systematic reviews have used a score of 19 for inclusion [19, 35]. Three studies were excluded from the review as they scored less than 19 in Hawker’s score [33]. The minimum score of the studies included in this review was 25, and the average score was 30.

Data extraction

The screening, quality appraisal and data extraction were conducted independently by two reviewers. The data extraction sheet provided in Additional file 4 has five sections. The initial section had information regarding the country and year of publication. The second section focused on the type of study, that is a survey, qualitative or mixed-method. In this section, study objectives, population and study setting were also described. Study sample, participants, inclusion and exclusion criteria, research design and methods were elucidated in the third section. The fourth section provided information on study findings and conclusions. The last section discussed the strengths and limitations of the study and biases.

Data synthesis

During Popay’s narrative synthesis, the first step was to identify a theoretical framework for the review that can contribute to the interpretation of review findings [21]. The theoretical lens of social exchange theory was used to interpret the themes generated during the synthesis [23]. The second step was to develop a preliminary synthesis. A preliminary synthesis was generated by providing a brief textual description of the studies informing the review. The studies informing this review were grouped according to the country, type of population studied and the factors influencing referral. The textual description helped the reviewers to be familiar with the data before analysis. The third step was to explore relationships within and between studies. The relationships were explored by representing the study findings as meaningful categories and themes and creating a thematic map. During this step, the reviewers also explored the heterogeneity of the included studies in terms of population, setting and typology. The fourth step was to assess the robustness of synthesis. It was done by critically reflecting the synthesis process and providing information about the limitation of the synthesis and possible sources of biases [21].

Results

Overview of studies

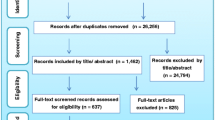

Out of 9336 initial database citations, 23 studies were included for synthesis. The PRISMA flow diagram for this review is provided in Fig. 1. Ten studies were qualitative, ten were surveys, and three were mixed-method studies. Twelve studies were from North America (nine USA and three Canada), seven from Europe (three from France, one each from Belgium, United Kingdom, Hungary and Cyprus), two from Australia and two from Asia (one each from Japan and Israel). The majority of the surveys and mixed-method studies were multi-centre studies spanning across several centres within the country and across countries. Moreover, they were often linked to professional cancer societies. The qualitative studies were mostly limited to one or more centres within a region. A detailed overview of the studies can be found in Table 2. There were only two studies on paediatric referrals [49, 53]. One had a mixed adult and paediatric population [49] and another a qualitative study of paediatric oncologists [53].

Review themes

Five themes developed during synthesis. They were a) presuppositions of oncologists and haematologists, b) power relationships and trust issues, c) making a palliative care referral: a daunting task, d) cost-benefit of a palliative care referral, and e) strategies to facilitate a palliative care referral. The themes, subthemes, and the explanatory narrative for the subthemes along with the citations are displayed in Table 3, and the thematic map of the review is visually represented in Additional file 5.

Presuppositions of oncologists and haematologists about palliative care referral

Data from this review suggests that oncologists and haematologists perceived palliative care referral as role conflict, abandonment, rupture of therapeutic alliance and loss of hope. Making a palliative care referral triggered negative emotions, and they felt that they have the self-efficacy to manage palliative care needs. These perceptions informed some of the tendencies that might have hindered palliative care referral.

Some studies reported views on role conflict [36, 43, 56]. Haematologists felt that their role was to cure and save their patients, and end of life discussions was not compatible with their role [56]. Haematologists viewed palliative care referral as a therapeutic failure and letting down the patient and their families [43]. Moreover, haematologists also felt that engaging with palliative care reflected poorly on their performance and credibility [56].

Oncologists and haematologists expressed views on abandonment [37, 43, 46, 58]. British haematologists and the French oncologists felt that their patients and families experienced abandonment when there was a change in focus of care and during discussing poor prognosis [43, 58].

Some studies reported views on the rupture of the therapeutic alliance [53, 56, 58]. Hungarian paediatric oncologists felt that parental anxiety associated with early palliative care referral impeded the therapeutic relationship [53]. Some French oncologists and haematologists felt that palliative care referral could jeopardise both the doctor-patient relationship and compromise treatment compliance [56, 58].

Oncologists and haematologists equated palliative care referral to loss of hope [54, 56, 58]. A desire to maintain hope was a barrier for palliative care referral among the Canadian and French oncologists [54, 58]. The French haematologists felt the need to reassure and inspire confidence in their patients and protect them from any information that caused a loss of hope [56].

Making a palliative care referral could trigger negative emotional reactions among some oncologists and haematologists [36, 43, 58]. French oncologists felt emotionally burdened while delivering the news of poor prognosis [58]. Belgian oncologists and British haematologists felt that close emotional bond resulted from knowing their patients over time [36, 43]. It made them emotional while making a referral. Moreover, some Belgian oncologists found it challenging to handle the emotional reactions of patients and families associated with palliative care referral [36].

Seven studies supported the view that oncologists and haematologists perceived they have the self-efficacy to manage palliative care needs [38, 40, 41, 46, 47, 55, 58]. Oncologists and haematologists felt that managing symptoms, providing psychosocial support and communicating with the patients are integral aspects of oncology and they felt that they had developed these skills in their oncology training [38, 40, 41].

Power relationships and trust issues

Data from this review suggests that oncologists and haematologists had the power to gatekeep the referral process and believed in competency-based trust. Many studies supported the view that oncologists and haematologists preferred to regulate the referral process and liked to control and coordinate the care process of their patients at all stages of their illness trajectories [36, 38, 42, 43, 45, 46]. The American oncologists perceived palliative care referral as loss of control [42, 47], and interference in the care process [45, 46]. In some studies, oncologists and haematologists liked to decide the timing of the referral [53, 56, 58]. Hungarian paediatric oncologists and the French oncologists and haematologists preferred to wait till the end of cancer treatment to make a palliative care referral [56, 58].

Synthesis of data from some studies shows that oncologists and haematologists have diminished trust in the competency of palliative care providers [38, 39, 46, 51, 58]. Japanese haematologists and French oncologists felt that palliative care providers have suboptimal assessment and management skills [39, 58]. Medical oncologists worldwide felt that the oncology training of palliative care providers was inadequate [38]. American oncologists questioned the reliability of palliative care providers as they were unable to differentiate a recoverable sick patient from a dying patient [51].

Making a palliative care referral: a daunting task

Data from this review suggests that oncologists and haematologists perceive the task of making a palliative care referral as daunting. They had to deal with the stigma associated with palliative care, navigate illness and treatment associated factors, address patient and family attitudes, and overcome organisational challenges. Moreover, a lack of referral criteria and limited palliative care resources made the referral process even more challenging.

Most studies supported the view that oncologists and haematologists had to deal with the stigma associated with palliative care. Oncologists and haematologists had to deal with the public stigma of palliative care due to the negative stereotyped association of palliative care with death [36, 39, 47, 52, 53]. European oncologists and haematologists felt that families were reluctant to discuss death and viewed discussing death as a taboo [36, 56, 56]. Moreover, families felt stressed during the end of life discussions and equated these conversations with abandonment and euthanasia [56, 58].

Oncologists and haematologists also had to deal with label avoidance stigma or the choice not to pursue a line of management due to stigma associated with the language used in relation to the illness or treatment [36, 48, 49, 53, 57, 58]. French oncologists felt that the term palliative care has a potential to induce fear [58], and the American lung cancer specialists believed that patients and their families get alarmed on mentioning palliative care [44]. British haematologists and American gynae-oncologists felt that the term palliative care required careful explanation, and they had to dispel negative connotations associated with the term [42, 43]. Hungarian paediatric oncologists and French oncologists suggested changing the term to comfort care or supportive care [53, 58].

In most studies, oncologists and haematologists elucidated illness-related factors either facilitating or hindering palliative care referral. Stage of the illness [45], its course [39, 43, 57] and complications [43] determined palliative care referral. Prognostication [48, 49, 54], cure potential [39, 40, 43, 54], availability of treatment options [47, 55], and decision-making challenges [50] also played an important role in palliative care referral. Presence of symptoms [40, 45, 48, 49, 55] and performance status [36] of the patient were the other factors determining palliative care referral.

Data from this review suggest that oncologists and haematologists felt that beliefs and expectations of patients and families hindered palliative care referral. Unrealistic expectation of cure [36, 50, 52, 54], unwillingness to discuss prognosis and non-curative approach [40, 44, 54], and reluctance to discuss palliative care referral [37, 41, 55] were certain attitudes that hindered palliative care referral.

In this review, oncologists and haematologists had to overcome organisational challenges that hindered palliative care referral. A lack of space and time to discuss palliative care was a significant barrier [36, 50, 52, 54]. American surgical oncologists and Belgian oncologists felt that hospital culture directed towards cure hindered referral [36, 50]. American surgical oncologists feared legal liability of palliative care referral and expressed reservations about opioid use [50]. Both American medical and surgical oncologists believed that insufficient documentation about a patient’s illness in the medical records constrained palliative care referral [36, 50].

Lack of palliative care referral guidelines [41, 43, 45], and uncertainty about when to refer [37, 39, 48] constrained palliative care referral. Belgian oncologists felt that lack of consensus among the oncologists about the timing of referral was also a limiting factor [36].

In this review, oncologists and haematologists perceived that palliative care resources are limited. Inadequate palliative care resources [41, 43, 51], fewer palliative care providers [37, 39], and limited access to palliative care [40, 50, 52] hindered palliative care referral. American oncologists felt that long waiting times for palliative care appointments and limited palliative care outpatient clinics were some of the other barriers for referral [47, 55].

Cost-benefit of palliative care referral

In this review, oncologists and haematologists have elucidated both the rewards and negative effects of making a palliative care referral. Pain and symptom management and psychosocial support are the well-known benefits of palliative care referral. In many studies included in this review, the oncologists and haematologists subscribe to the views on well-known benefits of palliative care referral. However, only a few studies elucidated lesser-known benefits of palliative care like facilitating goals of care discussion and shared decision-making. The Australian and American oncologists felt that palliative care improved the quality of life of their patients [40, 51]. Palliative care referral facilitated decision-making [42, 57] and enabled goals of care discussion [42, 44]. It also facilitated treatment completion [45], reduction in hospital stay [44], discharge planning [48, 49] and support for the patients in the community [41]. Oncologists and haematologists also experienced some direct benefits as it helped them to resolve family conflicts and saved the time of the oncologists [42, 45].

In this review, oncologists and haematologists felt that they had experienced some unintended negative outcomes of palliative care referral. In some studies, oncologists and haematologists felt that lack of congruence in communication between them and palliative care providers led to patients and families receiving mixed messages. They felt that palliative care communication could make patients and their families confused and overwhelmed [39, 43, 46, 47]. Moreover, they felt that palliative care providers have incorrect perception about the course of illness and treatment outcomes leading to inconsistencies in communication [45,46,47, 51]. The American oncologists emphasised the presence of an oncologist during the initial family meeting after palliative care referral [51].

Oncologists and haematologists felt that palliative care referral could risk curtailment of care of their patients. British and Japanese haematologists felt that palliative care providers are reluctant to consult haematology patients and the patients were unable to access blood products while receiving palliative care [39, 43]. The Australian medical oncologists and the American surgical oncologists felt that reluctance of palliative care providers to consult patients receiving active anti-cancer treatment could deprive management of these patients with palliative care needs [41, 50].

Strategies to facilitate palliative care referral

In half of the studies included in the review, oncologists and haematologists provided some strategies that could facilitate palliative care referral. Oncologists and haematologists felt that strategies like developing an integrated model of care, changing the name of palliative care and augmenting palliative care resources could facilitate palliative care referral.

Oncologists and haematologists thought that integrated model of care could be achieved by providing concurrent cancer treatment and palliative care [38, 41, 48], co-management of the patients [40, 41, 47] and by having an excellent inter-team communication [41, 42, 50]. American oncologists felt that oncology and palliative care have complementary roles and preferred palliative care teams to be embedded in oncology clinics [42, 51]. Lung cancer specialists from Cyprus and American oncologists felt that palliative care rotation should be part of oncology training [37, 47]. In some studies, oncologists and haematologists felt that rapport building between the palliative care team and patient and their families is essential to facilitate smooth transitions of care from oncology to palliative care [40, 41, 45, 46, 49, 57]. Some oncologists and haematologists supported changing the name of palliative care [45, 57, 58]. They felt that palliative care referral is likely to improve if the term palliative care is replaced with supportive care [48, 49, 58]. Oncologists and haematologists felt the need to improve the availability of services, consistency and continuity of care and more in-patient palliative care beds [38, 41, 46].

Subgroup analysis

Oncologists versus haematologists, adult versus paediatric physicians, and countries were the three subgroups that were analysed. Five studies included in this review captured the views of haematologists [39, 43, 47, 56, 57]. The haematologists had a higher negative perception of palliative care due to the term palliative care associated with death. They were less likely to refer and referred late due to complex unpredicted course of haematological illness and complications. Two studies captured the views of paediatric oncologists [49, 53]. Like haematologists, the paediatric oncologists also preferred to avoid the term palliative care. They also favoured waiting till the end of cancer treatment to make palliative care referral. The views of oncologists and haematologists across various countries included in the review were comparable.

Discussion

In a cancer care setting, oncologists and haematologists have the discretionary authority to make treatment decisions for their patients and act as gatekeepers [59]. Their views impact palliative care referral. In this review, few oncologists and haematologists expressed their concern regarding referee’s lack of professional competency and referrer’s self-efficacy to meet various palliative care needs. Competency-based trust is an expectation that the other person can perform a task effectively, and reduced trustworthiness can hinder engagement with a person or a service [60]. The discourse of oncologists and haematologists in this review in terms of power to control and coordinate the care of their patients and determining the timing of referral suggests power dependence in a relationship. Power relationships exist when a person is dependent on another for the things that they value [61]. Palliative care is an end speciality, and its providers are dependent on oncologists and haematologists for a referral [62]. Moreover, the public stigma and label avoidance stigma due to negative stereotyped association of palliative care with death gave them the stigma power, where the stigmatisers had the power to exclude the stigmatised [63].

In this review, oncologists and haematologists have drawn symbolic inferences about palliative care referral. They felt that palliative care referral symbolised the loss of hope, abandonment, break in the therapeutic relationship and role conflict. Symbolic perspectives could influence human cognition and motivation and might act as internal reinforcement affecting the referral behaviour [64].

An integrated approach is to bring together and align professional inputs, services and clinical management [65]. In this review, few oncologists have advocated for an integrated model of cancer care where cancer care and palliative care is provided concurrently. Moreover, they felt that oncologists and palliative care providers have a complementary role where oncologists provide cancer treatment and palliative care providers manage symptoms and improve quality of life. The integrated approach is not limited to making a referral or transfer of patient information [66]. It involves providing critical inputs that could change the attitudes of health care providers [67]. In this review, changing the name of palliative care and rebranding it as supportive care is a crucial input provided by the oncologists, which might enable integration. Moreover, palliative care rotation being part of oncology training and palliative care providers having knowledge and skills in oncology were the other inputs that could facilitate integration. Palliative care participation in the multidisciplinary cancer meetings and coordination of care between the two teams can assist integration [68,69,70]. Moreover, having a standardised care pathway contextualised to the region or country might facilitate integration [71]. In this review, oncologists emphasised the need for excellent inter-team communication and palliative care embedded in the oncology clinics as a means to achieve integration.

Social exchange theory as a framework for interpreting review findings

The process of referral is a social action where there is a temporary or permanent sharing of responsibility for patient care between the referrer and the referee [72]. Making a referral is a social behaviour [72]. Social Exchange Theory (SET) is the theorisation of social behaviour [73]. It is viewed in terms of social actors interacting to meet their needs, and the purpose of the interaction is to seek reward and avoid the cost [23]. The initial SET proposed by Homans was limited to the task, rewards and cost of interaction [74]. However, it was expanded by Blau and Emerson to include power relationships and cognitive perceptions of the social actors [61, 75]. The referral behaviour is usually based on referrer’s presuppositions towards the referee, the power relationship between the referrer and referee, the task of referral, rewards accrued, costs incurred and equity of relationship [76]. Presuppositions are emotions or feelings, which is an internal response to a social event [64]. Sentiments are affective states of emotion that have an evaluative role and influence social action [77, 78]. Therefore, presuppositions about palliative care referral formed tendencies, which had the potential to influence referral behaviour [24, 79].

According to SET, power and status of actors are considered as key factors determining the nature of exchange [77]. In this review, a few oncologists have requested the palliative care providers to change their name [45, 48, 49]. This request to rebrand [80] may also suggest a form of power imbalance as few services have conceded to that request [81]. Homans focused on the power of reward in social exchange [74]. In this review, the reward of palliative care was restricted to a couple of roles like pain management and psychosocial support. A study that used SET to understand non-terminal palliative care referral practices for Parkinson’s disease patients showed that endorsement of the rewards of palliative care referral by the neurologists was one of the strong predictors of referral [82]. The focus of Emerson’s modification of SET moved beyond the power of reward into coercive power [61]. Coercive power is the ability to control the negative events or the costs of exchange by the social actors in power advantaged position [61]. Inconsistencies in communication, curtailment of care and the challenges associated with accessing palliative care were perceived negatively by the oncologists that hindered future referral.

The review findings pertaining to the stigma of palliative care referral and stigma as a barrier to social exchange were the other perceptions explored using the SET. Cook and Emerson’s work on SET added cognitive perspectives and social structures as important components of exchange [83]. It also facilitated elucidating the individual and organisational factors in this review hindering palliative care referral. According to Emerson, in an exchange relationship, the power inequalities between the social actors can be balanced by coalition formation, division of labour and network extension [61]. Coalition formation is a mechanism by which a social actor in a less powerful position can gain advantage through collaboration [61]. In this review, few oncologists have advocated for an integrated model of cancer care where cancer care and palliative care is provided concurrently. The network extension is where the less powerful actor balance power by adding new partners to facilitate exchange [61]. The division of labour is where each social actor works according to his skills and specialisation towards fruition [61]. In this review, oncologists felt that co-management of patients by both the disciplines facilitated integration.

In this review, oncologists and haematologists offered some solutions to make this relationship equitable. Equity is appraising the rewards and costs on the background of sentiments, the intricacy of the tasks and outcomes [74]. According to SET, in an inequitable situation, people explore alternate choices, compare the present situations with alternate choices and may leave the situation [23]. However, in this review, oncologists offered strategies to facilitate palliative care referral instead of leaving the relationship. Sometimes people remain in the relationship even when they are inequitable for reasons that go beyond simple economic logic [84]. For oncologists and haematologists not referring to palliative care may not be an option, as there are limited alternatives to palliative care for a patient with advanced cancer. Therefore, “finding equitable solutions” can be added to the social exchange theory alongside “comparison level for alternatives” [23].

Limitations and strengths

Three survey studies had a low response rate [37, 38, 40]. It could create a potential response bias as the respondents who completed this survey were the ones who are familiar with palliative care. Although they were low response surveys, each of these studies had a significant number of participants who provided views on facilitators and barriers for specialist palliative care referral. Three studies had respiratory physicians, colorectal surgeons and internists as participants along with oncologists [37, 40, 44]. Although some of the participants in these studies were not oncologists by training their views were included in the review as they were actively involved in the cancer care of the patients. Moreover, it was difficult to disaggregate their role in these studies. A few studies exploring the views of cancer providers about palliative care referral were excluded [9, 25, 85,86,87,88,89,90,91], as these studies had a heterogeneous mixture of physicians, physician assistants, nurses and social workers. It would not have been possible to disaggregate the physician views from the other healthcare provider’s views. The year of publication of the studies included in the review ranged from 2003 to 2019. However, most of the included studies were published in the last five years. The review findings of the earlier studies may not truly represent the contemporary attitudes of oncologists and haematologists towards palliative care referral.

The presence of two reviewers enabled comparison of the search results, identifying methodological strengths and weaknesses, and it facilitated the synthesis of the findings in a transparent manner. Disagreements were resolved by mutual consultation. The search terms were finalised after consulting with an information assistant. The articles included for the review were selected after appraisal, checking for relevance and scoring for methodological rigour. The synthesis was conducted systematically according to the narrative synthesis steps. Despite a few limitations, the themes derived from the systematic review were able to answer the review question satisfactorily. Findings from the surveys, qualitative studies and mixed methods studies mirrored each other, adding to the strength of the synthesis. The review had a mixed typology of studies, and the participants had diverse oncology backgrounds, traversing four continents. This heterogeneity added depth to the findings and their generalisability.

Conclusion

The findings of this review suggest that some oncologists and haematologists liked to control and coordinate the care of their patients at all stages of illness trajectories and determine the timing of referral. They considered palliative care referral as abandonment, a break in the therapeutic relationship and loss of hope. They also expressed concerns regarding the professional competency of the palliative care providers and felt that they had the self-efficacy to manage the palliative care needs. Although illness-related factors acted as triggers for palliative care referral, the stigma associated with palliative care, patient and family attitudes, organisational challenges, lack of referral guidelines and limited palliative care resources made referral a daunting task. The findings of this review suggest that the majority of oncologists appreciated the pain and symptom management and psychosocial support role of palliative care. Lesser-known roles of palliative care were seldom elucidated. Some oncologists and haematologists felt that palliative care referral comes with a cost due to incongruencies in communication and curtailment of care. They felt that an integrated model of care, changing the name of palliative care and augmenting palliative care resources might facilitate a referral.

Future considerations

In this review, views of paediatric oncologists are underrepresented as only two studies included in this review had their views. Therefore, there is scope for future research to know the views of paediatric oncologists and haematologists on palliative care referral. Moreover, a review exploring the views of patients and family caregivers on palliative care referral, and views of palliative care providers on receiving a referral from oncologists and haematologists may further bridge the knowledge gaps in palliative care referral.

Implications for policy and practice

Review findings have several implications on policy and practice. There is a need for palliative care trainees to have training in oncology, and likewise, there is a need for oncology trainees to have palliative care training. Palliative care providers regularly joining the multidisciplinary team meetings might provide an excellent opportunity for both the teams to bond and build confidence, which could better inter-team communication. Moreover, to facilitate integration, a rebranding strategy is probably required.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta Medica dataBASE

- MEDLINE:

-

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

- PICo:

-

Population, Phenomenon of Interest and Context

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- SET:

-

Social Exchange Theory

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

Gu X, Cheng W, Chen M, Liu M, Zhang Z. Timing of referral to inpatient palliative care services for advanced cancer patients and earlier referral predictors in mainland China. Palliative Supportive Care. 2016;14(5):503–9.

Michael N, Beale G, O'Callaghan C, et al. Timing of palliative care referral and aggressive cancer care toward the end-of-life in pancreatic cancer: A retrospective, single-centre observational study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-019-0399-4.

Taniwaki L, Serrano Usón Junior PL, Rodrigues De Souza PM, Lobato Prado B. Timing of palliative care access and outcomes of advanced cancer patients referred to an inpatient palliative care consultation team in Brazil. Palliative and Supportive Care; 2018.

Vanbutsele G, Deliens L, Cocquyt V, Cohen J, Pardon K, Chambaere K. Use and timing of referral to specialized palliative care services for people with cancer: A mortality follow-back study among treating physicians in Belgium. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0210056. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210056.

Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, Seitz R, Morgenstern N, Saito S, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):993–1000.

Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, Muzikansky A, Lennes IT, Heist RS, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(4):394–400.

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42.

Dalberg T, McNinch NL, Friebert S. Perceptions of barriers and facilitators to early integration of pediatric palliative care: a national survey of pediatric oncology providers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(6):e26996.

Kars MC, van Thiel GJ, van der Graaf R, Moors M, de Graeff A, van Delden JJ. A systematic review of reasons for gatekeeping in palliative care research. Palliat Med. 2016;30(6):533–48.

Burnham JF. Scopus database: a review. Biomed Digit Libr. 2006;3:1.

Ahmed N, Bestall JC, Ahmedzai SH, Payne SA, Clark D, Noble B. Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. Palliat Med. 2004;18(6):525–42.

Dalal S, Bruera S, Hui D, Yennu S, Dev R, Williams J, et al. Use of palliative Care Services in a Tertiary Cancer Center. Oncologist. 2016;21(1):110–8.

Hui D, Meng YC, Bruera S, Geng Y, Hutchins R, Mori M, et al. Referral criteria for outpatient palliative Cancer care: a systematic review. Oncologist. 2016;21(7):895–901.

Howell DA, Shellens R, Roman E, Garry AC, Patmore R, Howard MR. Haematological malignancy: are patients appropriately referred for specialist palliative and hospice care? A systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. Palliat Med. 2011;25(6):630–41.

Kirolos I, Tamariz L, Schultz EA, Diaz Y, Wood BA, Palacio A. Interventions to improve hospice and palliative care referral: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(8):957–64.

Hui D, Bruera E. Models of integration of oncology and palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4(3):89–98.

Burt J, Raine R. The effect of age on referral to and use of specialist palliative care services in adult cancer patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2006;35(5):469–76.

Firn J, Preston N, Walshe C. What are the views of hospital-based generalist palliative care professionals on what facilitates or hinders collaboration with in-patient specialist palliative care teams? A systematically constructed narrative synthesis. Palliat Med. 2016;30(3):240–56.

Stern C, Jordan Z, McArthur A. Developing the review question and inclusion criteria. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(4):53–6.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version. 2006;1:b92.

Okoli C. A critical realist guide to developing theory with systematic literature reviews. Available at SSRN 2115818. 2012.

Ekeh PP. Social exchange theory: the two traditions: Heinemann London; 1974.

Collier A. Critical realism: an introduction to Roy Bhaskar's philosophy; 1994.

Dalberg T, Jacob-Files E, Carney PA, Meyrowitz J, Fromme EK, Thomas G. Pediatric oncology providers' perceptions of barriers and facilitators to early integration of pediatric palliative care. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(11):1875–81.

Johnson C, Girgis A, Paul C, Currow DC, Adams J, Aranda S. Australian palliative care providers' perceptions and experiences of the barriers and facilitators to palliative care provision. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(3):343–51.

Twamley K, Craig F, Kelly P, Hollowell DR, Mendoza P, Bluebond-Langner M. Underlying barriers to referral to paediatric palliative care services: knowledge and attitudes of health care professionals in a paediatric tertiary care Centre in the United Kingdom. J Child Health Care. 2014;18(1):19–30.

Ramer SL. Site-ation pearl growing: methods and librarianship history and theory. J Med Libr Assoc. 2005;93(3):397–400.

Chang AA, Heskett KM, Davidson TM. Searching the literature using medical subject headings versus text word with PubMed. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(2):336–40.

Bradshaw PJ. Characteristics of clients referred to home, hospice and hospital palliative care services in Western Australia. Palliat Med. 1993;7(2):101–7.

Eyers JE. Searching bibliographic databases effectively. Health Policy Plan. 1998;13(3):339–42.

Hinde S, Spackman E. Bidirectional citation searching to completion: an exploration of literature searching methods. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(1):5–11.

Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(9):1284–99.

Oishi A, Murtagh FE. The challenges of uncertainty and interprofessional collaboration in palliative care for non-cancer patients in the community: a systematic review of views from patients, carers and health-care professionals. Palliat Med. 2014;28(9):1081–98.

Flemming K. The use of morphine to treat cancer-related pain: a synthesis of quantitative and qualitative research. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;39(1):139–54.

Horlait M, Chambaere K, Pardon K, Deliens L, Van Belle S. What are the barriers faced by medical oncologists in initiating discussion of palliative care? A qualitative study in Flanders. Belgium Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(9):3873–81.

Charalambous H, Pallis A, Hasan B, O'Brien M. Attitudes and referral patterns of lung cancer specialists in Europe to specialized palliative care (SPC) and the practice of early palliative care (EPC). BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13(1):59.

Cherny NI, Catane R. Attitudes of medical oncologists toward palliative care for patients with advanced and incurable cancer: report on a survery by the European Society of Medical Oncology Taskforce on palliative and supportive care. Cancer. 2003;98(11):2502–10.

Morikawa M, Shirai Y, Ochiai R, Miyagawa K. Barriers to the collaboration between hematologists and palliative care teams on relapse or refractory leukemia and malignant lymphoma Patients' Care: a qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(10):977–84.

Johnson CE, Girgis A, Paul CL, Currow DC. Cancer specialists' palliative care referral practices and perceptions: results of a national survey. Palliat Med. 2008;22(1):51–7.

Ward AM, Agar M, Koczwara B. Collaborating or co-existing: a survey of attitudes of medical oncologists toward specialist palliative care. Palliat Med. 2009;23(8):698–707.

Hay CM, Lefkowits C, Crowley-Matoka M, Bakitas MA, Clark LH, Duska LR, et al. Gynecologic oncologist views influencing referral to outpatient specialty palliative care. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27(3):588–96.

Wright B, Forbes K. Haematologists' perceptions of palliative care and specialist palliative care referral: a qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(1):39–45.

Smith CB, Nelson JE, Berman AR, Powell CA, Fleischman J, Salazar-Schicchi J, Wisnivesky JP. Lung cancer physicians’ referral practices for palliative care consultation. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(2):382–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdr345.

Rhondali W, Burt S, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Bruera E, Dalal S. Medical oncologists' perception of palliative care programs and the impact of name change to supportive care on communication with patients during the referral process. A qualitative study. Palliat Support Care. 2013;11(5):397–404..

Schenker Y, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, Rabow MW, Smith CB, White DB, et al. Oncologist factors that influence referrals to subspecialty palliative care clinics. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(2):e37–44.

LeBlanc TW, O'Donnell JD, Crowley-Matoka M, Rabow MW, Smith CB, White DB, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among hematologic malignancy specialists: a mixed-methods study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):e230–8.

Wentlandt K, Krzyzanowska MK, Swami N, Rodin GM, Le LW, Zimmermann C. Referral practices of oncologists to specialized palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(35):4380–6.

Wentlandt K, Krzyzanowska MK, Swami N, Rodin G, Le LW, Sung L, et al. Referral practices of pediatric oncologists to specialized palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(9):2315–22.

Suwanabol PA, Reichstein AC, Suzer-Gurtekin ZT, Forman J, Silveira MJ, Mody L, et al. Surgeons' perceived barriers to palliative and end-of-life care: a mixed methods study of a surgical society. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(6):780–8.

Gidwani R, Nevedal A, Patel M, Blayney DW, Timko C, Ramchandran K, et al. The appropriate provision of primary versus specialist palliative care to Cancer patients: Oncologists' perspectives. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(4):395–403.

Cripe JC, Mills KA, Kuroki LK, Wan L, Hagemann AR, Fuh KC, et al. Gynecologic Oncologists' perceptions of palliative care and associated barriers: a survey of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2019;84(1):50–5.

Nyirő J, Zörgő S, Enikő F, Hegedűs K, Hauser P. The timing and circumstances of the implementation of pediatric palliative care in Hungarian pediatric oncology. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177(8):1173–9.

Ethier JL, Paramsothy T, You JJ, Fowler R, Gandhi S. Perceived barriers to goals of care discussions with patients with advanced Cancer and their families in the ambulatory setting: a multicenter survey of oncologists. J Palliat Care. 2018;33(3):125–42.

Feld E, Singhi EK, Phillips S, Huang LC, Shyr Y, Horn L. Palliative care referrals for advanced non-small-cell lung Cancer (NSCLC): patient and provider attitudes and practices. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019;20(3):e291–e8.

Prod'homme C, Jacquemin D, Touzet L, Aubry R, Daneault S, Knoops L. Barriers to end-of-life discussions among hematologists: a qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2018;32(5):1021–9.

Tricou C, Munier S, Phan-Hoang N, Albarracin D, Perceau-Chambard É, Filbet M. Haematologists and palliative care: a multicentric qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019:bmjspcare-2018-001714. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001714. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 30808629.

Sarradon-Eck A, Besle S, Troian J, Capodano G, Mancini J. Understanding the barriers to introducing early palliative Care for Patients with advanced Cancer: a qualitative study. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(5):508–16.

McGorty EK, Bornstein BH. Barriers to physicians' decisions to discuss hospice: insights gained from the United States hospice model. J Eval Clin Pract. 2003;9(3):363–72.

Lee HJ. The role of competence-based trust and organizational identification in continuous improvement. J Manag Psychol. 2004;19(6):623–39.

Emerson RM. Social exchange theory, annual review of sociology. Ann Rev. 1976;1:335–62.

Walshe C, Todd C, Caress A-L, Chew-Graham C. Judgements about fellow professionals and the management of patients receiving palliative care in primary care: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(549):264–72.

Link BG, Phelan J. Stigma power. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:24–32.

Lawler EJ. An affect theory of social exchange. Am J Sociol. 2001;107(2):321–52.

Gröne O, Garcia-Barbero M. Integrated care: a position paper of the WHO European Office for Integrated Health Care Services. Int J Integr Care. 2001;1(2). https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.28.

van der Klauw D, Molema H, Grooten L, Vrijhoef H. Identification of mechanisms enabling integrated care for patients with chronic diseases: a literature review. Int J Integr Care. 2014;14:e024. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.1127.

Davis M, Strasser F, Cherny N. How well is palliative care integrated into cancer care? A MASCC, ESMO, and EAPC project. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(9):2677–85.

Ewert B, Hodiamont F, van Wijngaarden J, Payne S, Groot M, Hasselaar J, et al. Building a taxonomy of integrated palliative care initiatives: results from a focus group. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2016;6(1):14.

Nottelmann L, Jensen LH, Vejlgaard TB, Groenvold M. A new model of early, integrated palliative care: palliative rehabilitation for newly diagnosed patients with non-resectable cancer. (Original Article)(Reprint). Supportive Care in Cancer. 2019;27(9):3291.

Siouta N, Van Beek K, van der Eerden ME, Preston N, Hasselaar JG, Hughes S, et al. Integrated palliative care in Europe: a qualitative systematic literature review of empirically-tested models in cancer and chronic disease. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:56.

Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, Albreht T, Anderson R, Bruera E, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: a lancet oncology commission. The Lancet Oncology. 2018;19(11):e588–653.

Shortell SM. Determinants of physician referral rates: an exchange theory approach. Med Care. 1974;12(1):13–31.

Ekeh PP. Social exchange theory : the two traditions: Heinemann educational; 1974.

Homans GC. Social behavior as exchange. Am J Sociol. 1958;63(6):597–606.

Blau P. Social exchange//international encyclopedia of the social sciences. V. 7. NY: Macmillan; 1968.

Kinchen KS, Cooper LA, Levine D, Wang NY, Powe NR. Referral of patients to specialists: factors affecting choice of specialist by primary care physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(3):245–52.

Gordon SL. The sociology of sentiments and emotion: Social psychology. New York: Routledge; 2017. p. 562–92.

Shelly RK. How sentiments organize social action. Sociol Compass. 2016;10(3):230–41.

Danermark B, Ekström M, Karlsson JC. Explaining society: critical realism in the social sciences: Routledge; 2019.

Berry LL, Castellani R, Stuart B. The branding of palliative care. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(1):48–50.

Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D, Nguyen L, Chacko R, Li Z, et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist. 2011;16(1):105–11.

Prizer LP, Gay JL, Perkins MM, Wilson MG, Emerson KG, Glass AP, et al. Using social exchange theory to understand non-terminal palliative care referral practices for Parkinson's disease patients. Palliat Med. 2017;31(9):861–7.

Cook KS, Emerson RM. Power, equity and commitment in exchange networks. Am Sociol Rev. 1978:721–39.

Redmond MV. Social exchange theory; 2015.

Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Ahles T. Oncologists' perspectives on concurrent palliative care in a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center. Palliat Support Care. 2013;11(5):415–23.

Buckley de Meritens A, Margolis B, Blinderman C, Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Shen MJ, et al. Practice patterns, attitudes, and barriers to palliative care consultation by gynecologic oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(9):e703–e11.

Centeno C, Garralda E, Carrasco JM, den Herder-van der Eerden M, Aldridge M, Stevenson D, et al. The palliative care challenge: analysis of barriers and opportunities to integrate palliative Care in Europe in the view of National Associations. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(11):1195–204.

Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, Del Fabbro E, Swint K, Li Z, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: what's in a name?: a survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer. 2009;115(9):2013–21.

Hui D, Cerana MA, Park M, Hess K, Bruera E. Impact of Oncologists' attitudes toward end-of-life care on Patients' access to palliative care. Oncologist. 2016;21(9):1149–55.

Keim-Malpass J, Mitchell EM, Blackhall L, DeGuzman PB. Evaluating stakeholder-identified barriers in accessing palliative care at an NCI-designated Cancer center with a rural catchment area. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(7):634–7.

Kirby E, Broom A, Good P, Wootton J, Adams J. Medical specialists' motivations for referral to specialist palliative care: a qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4(3):277–84.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank faculty and staff of the International Observatory on End of Life Care, Lancaster University, Department of Palliative Medicine and Supportive Care, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal and Department of Palliative Medicine, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai who have directly and indirectly helped us in providing their views and experiences, which has helped us in preparation of this review.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NS and AG made a substantial contribution to the concept and design of the work; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. NS, AG, SH, and NP drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. The systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO: CRD42018091481(https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php? RecordID = 91481).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Nancy Preston is a section editor (Psychosocial), Naveen Salins is an Associate Editor (Palliative care in other conditions) of BMC Palliative Care. A Ghoshal, and S Hughes declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Search Terms.

Additional file 2.

List of Journals Hand Searched.

Additional file 3.

Hawker’s tool used for assessing the methodological rigour of the included studies in the review.

Additional file 4.

Data Extraction Form.

Additional file 5.

Thematic Map of Review Findings.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Salins, N., Ghoshal, A., Hughes, S. et al. How views of oncologists and haematologists impacts palliative care referral: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 19, 175 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00671-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00671-5