Abstract

Background

Depression and cognitive impairment (CI) are important non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease (PD) and related syndromes, but it is not clear how well they are recognised in daily practice. We have studied the diagnostic performance of experienced neurologists on the topics depression and cognitive impairment during a routine encounter with a patient with recent-onset parkinsonian symptoms.

Methods

Two experienced neurologists took the history and examined 104 patients with a recent-onset parkinsonian disorder, and assessed the presence of depression and cognitive impairment. On the same day, all patients underwent a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale test, and a Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease-Cognition-test (SCOPA-COG).

Results

The sensitivity of the neurologists for the topic depression was poor: 33.3%. However, the specificity varied from 90.8 to 94.7%. The patients’ sensitivity was higher, although the specificity was lower. On the topic CI, the sensitivity of the neurologists was again low, in a range from 30.4 up to 34.8%: however the specificity was high, with 92.9%. The patients’ sensitivity and specificity were both lower, compared to the number of the neurologists.

Conclusions

Neurologists’ intuition and clinical judgment alone are not accurate for detection of depression or cognitive impairment in patients with recent-onset parkinsonian symptoms because of low sensitivity despite of high specificity.

Trial registration

(ITRSCC)NCT0036819.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depression and cognitive impairment (CI) are increasingly appreciated as important non-motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and related syndromes [1–11]. Early recognition and diagnosis of both is important as treatment may increase quality of life of patients [12–22], but this is reported to be hampered at different levels. Many depressed patients are not aware of their problems [23] and, although caregivers sometimes have better judgment [24], they can also be misled by personality issues [25]. Non-psychiatrist physicians appear not to do much better, as numerous studies have shown that they perform significantly worse than validated questionnaires [26–39]. The presence of CI also leads physicians to overestimate the presence of depression [40].

Non-motor symptoms in PD tend to be under-diagnosed compared to motor problems, which seems logical as the latter are the primary expertise of neurologists. Some studies have compared different instruments to diagnose CI and depression in PD [41–43], but few have studied how accurate the diagnostic process is in normal daily practice [44, 45]. Most often, neurologists focus on motor symptoms and evaluate possible CI and depression implicitly during their consultation [46]. These consultations are often too short to conduct a formal validated test for depression and/or CI. We studied this implicit diagnostic process to assess its accuracy in a consecutive series of patients referred for analysis of a parkinsonian disorder of very recent onset. We focused on this patient group as research on this question has hitherto been done only in patients with a well-established diagnosis of PD.

Methods

The present study was nested in a larger, prospective study testing the diagnostic accuracy of transcranial duplex scanning (TCD) of the substantia nigra (SN) in the brainstem as an instrument to diagnose PD in patients with a parkinsonism of unclear origin [47].

We invited 283 consecutive patients, who were referred to two neurology outpatient clinics, for analysis of clinically unclear parkinsonian disorder (Neurology Outpatient Clinics of the Maastricht University Medical Centre in Maastricht and of the Maasland Hospital in Sittard, both in The Netherlands). Patients, whose parkinsonism was clearly diagnosable at the first visit, were excluded from the study. For further details see our protocol described elsewhere [47]. Finally, we enrolled 242 patients in our study (see Figure 1) after written informed consent for participation by each patient.

After two years, all patients were re-examined by a pair of neurologists for a final clinical diagnosis. The neurologists were specialists in movement disorders, with more than ten years’ experience in this field. These investigators were blinded for all prior test results from these patients. In planning these visits, we made sure that neither of the two neurologists had ever seen the patient. They were asked to interview and examine the patient, guided by a standard form (see Additional file 1). Family or spouse were allowed to be present at this consultation, but were asked to refrain from answering any questions. Neurologists were not given any objective scales for depression or cognitive impairment. After this consultation, the patient left the room.

The specialists were then asked to indicate on a form if they thought the patient was depressed and if CI was present. There was no communication between the raters on this decision. They were also asked to reach an independent clinical diagnosis, and record it. After this, they were asked to discuss the patient, and reach a final, consensus diagnosis, which served as the “gold standard” in the TCD study [47]. On the day of this evaluation, all patients were asked to complete the Hamilton Depressing Rating Scale (in the text further shortened to ‘Hamilton’) and the Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease-Cognition (SCOPA-COG). Both tests have shown their reliability and validity as instruments to assess either depression or CI, both with and without PD [48–53]. The maximum possible score on the SCOPA-COG is 43. A score of 20 or lower is defined as CI [52, 53]. The maximum possible score on the 17 item Hamilton is 52. A score 0 to 7 on the Hamilton implies normal/-borderline mood, score between 8 and 15 indicates a mild depression; a score in the range of 16 to 26 indicates a moderate depression; and a score of 27 or higher implies severe depression [50, 51]. The results of these tests were not provided to the patients. We also asked the patients the following questions: ‘Do you think you have more difficulties with your memory than people of the same age as you?’ and ‘Did you experience feelings of depression, most of the time during the last month?’ to evaluate their insight about the presence of CI and depression.

The primary objective of this study was to define the accuracy, namely, the sensitivity and specificity of the neurologists’ clinical judgement regarding the presence of CI and depression. The secondary objective was to evaluate the degree of agreement on the diagnosis of CI and depression between the patient himself and the two neurologists. SPSS 16.0 for windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The accuracy of the clinical judgement of the neurologists was evaluated by the means of specificity and sensitivity. The inter-rater agreement was evaluated by the Kappa statistics.

Results

We had originally enrolled 242 patients into the TCD study (see Figure 1). Follow-up after two years took place between September 2008 and September 2010. Thirty patients (12,4%) had died and 108 patients (44,2%) were unable or unwilling to undergo a second evaluation. The group lost to follow up were significantly older (p = 0,034) and had a higher mean Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) at enrollment (p = 0,031). However there were no significant differences in the distribution of the final diagnoses compared to the patients included in the present study. No correlation was found between either the UPDRS scores or results on the Hamilton and SCOPA-COG and the final diagnoses after two years follow-up.

For the present study, 104 patients (65 male, 39 female) were evaluated. The mean age was 70,3 (range 44–90) years. After two years follow-up, 62,5% of the patients used antiparkinson medication,13,5% antidepressants, and 3,8% neuroleptics. No one used cognitive enhancers. The final clinical diagnosis was PD in 53 (51%) patients. For further patient characteristics, see Table 1. The diagnostic groups were demographically similar. The remaining 15 (14%) patients without parkinsonism had alternative diagnoses, such as, isolated tremor, orthostatic tremor, tardive dyskinesia, multi-infarct dementia, Alzheimer disease, stroke, hypoxic encephalopathy, and psychogenic disorder.

Cognitive impairment

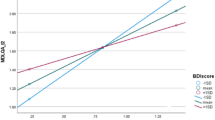

In total 102 patients were able to complete the SCOPA-COG, two patients were too tired after the consultation with the neurologists, and therefore, were not able to complete this test. The mean SCOPA-COG score was 21,1 with a range of 4 to 36. See Table 2 for the results on CI ‘diagnoses’ by the neurologist compared with the SCOPA-COG scores.

The sensitivity of neurologist 1 for ‘diagnosing’ CI was 34,8% and of neurologist 2 30,4% (see Table 3). Specificity of both neurologists was 92,9%.

In answer to the question ‘Do you think you have more difficulties with your memory than people of the same age as you?’, 19 (18,6%) said ‘yes’, 77 (75,5%) said ‘no’, and 6 (5,9%) ‘I do not know’. See Table 2 for the results on this ‘self-diagnosis’ of the patients on CI combined with their SCOPA-COG scores. Because six patients could not answer the question with ‘yes’ or ‘no’, we excluded them from this analysis. Therefore the sensitivity of self-diagnosis of CI by the patient was 27,3%. Its specificity was 86,5%.

The agreement between neurologist 1 and neurologist 2 was good with a kappa value of 0,74 (95% confidence interval 0,57–0,91) (see Table 3). However, the agreement between the neurologists and the patient was much lower with a kappa value varying between 0,34 (95% confidence interval 0,12–0,56) and 0,44 (95% confidence interval 0,23–0,66).

Depression

In total, 103 patients were able to complete the Hamilton (one patient was too tired after the consultation and was not able to complete this test). The mean Hamilton score was 5,5 with a range of 0 to 26. In this study, none of the patients had a score of 27 or higher. We defined depression at the total score of 8 or higher on the Hamilton.

See Table 2 for the results on the depression diagnosed by the neurologists compared to the patients’ Hamilton score. The sensitivity of depression diagnosis by both neurologists was 33,3%, specificity of neurologist 1 was 90,8% and of neurologist 2 was 94,7% (see Table 3).

In answer to the question ‘Did you experience feelings of depression, most of the time this last month?’, 40 (38,8%) said ‘yes’, 56 (54,4%) said ‘no’, and 7 (6,8%) ‘I do not know’. See Table 2 for the results on ‘self-diagnosis’ by the patients compared with their Hamilton score. Because 7 patients could not answer the question with ‘yes’ or ‘no’, we excluded them from this analysis. Therefore, the sensitivity of the patients’ self-diagnosis of depression was 73,1%. Its specificity was 70,0%.

The agreement between neurologist 1 and neurologist 2 was good with a kappa value of 0,62 (95% confidence interval 0,39–0,85) (see Table 3). Agreement between neurologists and patients was lower, with a kappa value varying between 0,28 (95% confidence interval 0,12–0,43) and 0,43 (95% confidence interval 0,27–0,60).

Discussion

We studied the accuracy of neurologists’ ability to diagnose depression and CI in patients with parkinsonian symptoms, in a way that most closely resembles normal daily clinical neurology practice, as a definite diagnosis of a parkinsonian syndrome is often not possible in the first few years. And, while the neurologists in our study were very experienced in PD and spent on average more time per patient than normal, we speculate that their results might even be somewhat inflated.

A limitation of the study is the use of psychometric scales as a proxy for the diagnoses of CI and depression. While these can not, of course, replace a complete diagnostic work-up by a specialised psychiatrist with a psychometric battery, we do feel that the results show that there is probably a considerable underestimation of the presence of these clinical problems also in patients with a very recent-onset of a parkinsonian disorder. Another limitation of our study is the large number of patients lost to follow-up. This could have biased our population towards one with less morbidity, thus increasing diagnostic difficulty. From the age and UPDRS-scores one can infer that PD patients with more severe disease and thus with possibly more severe depression and CI were underrepresented in this study.

We found that this implicit diagnostic process by neurologists is far less accurate than validated tests. The prevalences of both depression and CI found in our study, are representative for the general population of PD patients [54, 55].

We found that neurologists underestimated the number of patients with CI, by up to 70%. They did somewhat better than the patients themselves. Compared to other studies, our neurologists’ diagnostic sensitivity for CI was lower than those of general practitioners (GP’s), although both had a high specificity [34–40]. Our data on the recognition of CI are in line with two earlier studies on PD patients, which both found the majority of symptoms going unrecognised and untreated. However, one of those was a retrospective chart review and the other, prospective, study involved older, well-established PD patients. We did not confirm earlier research that the presence of CI leads to overestimating of depression by doctors [40].

In ‘diagnosing’ depression, our neurologists showed low sensitivity and high specificity. ‘Self-diagnosis’ of depression by the patient had a higher sensitivity compared to the neurologists, although the specificity was lower. The neurologists missed up to 67% of the patients with depression. The patients in our study overestimated the presence of depression. Presence of CI had no influence on the insight of the patients on depression. ‘Diagnostic accuracy’ of depression by our neurologists was comparable to GP’s [26], but self-diagnosis of depression in our patient population had a remarkably higher sensitivity than in an earlier study done by Watson [24]. However, that study only included patients with dementia, and this may explain this difference.

Conclusions

Intuition and clinical judgment are not enough for a neurologist to recognize depression and/or cognitive problems in patients with recent-onset parkinsonian syndromes, such as, PD and atypical parkinsonian syndromes (APS). It is important to realize this, considering the consequences of untreated depression and CI. Our neurologists had a high specificity diagnosing CI and depression, but at the same time missed more than half of the patients with these problems. Patients themselves are not better at self-diagnosing these non-motor symptoms.

References

Reichmann H, Schneider C, Lohle M: Non-motor features of Parkinson’s disease: depression and dementia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009, 15 (Suppl 3): S87-S92.

Bassetti CL: Nonmotor Disturbances in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2011, 8 (3): 95-108. 10.1159/000316613.

Chaudhuri KR, Odin P: The challenge of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Prog Brain Res. 2010, 184: 325-341.

Chaudhuri KR, Naidu Y: Early Parkinson’s disease and non-motor issues. J Neurol. 2008, 255 (Suppl 5): 33-38.

Lohle M, Storch A, Reichmann H: Beyond tremor and rigidity: non-motor features of Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2009, 116 (11): 1483-1492. 10.1007/s00702-009-0274-1.

Park A, Stacy M: Non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2009, 256 (Suppl 3): 293-298.

Ziemssen T, Reichmann H: Non-motor dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007, 13 (6): 323-332. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.12.014.

Rodriguez-Violante M, et al: Prevalence of non-motor dysfunction among Parkinson’s disease patients from a tertiary referral center in Mexico City. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010, 112 (10): 883-885. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.07.021.

Dickson DW, et al: Neuropathology of non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009, 15 (Suppl 3): S1-S5.

Colosimo C, et al: Non-motor symptoms in atypical and secondary parkinsonism: the PRIAMO study. J Neurol. 2010, 257 (1): 5-14. 10.1007/s00415-009-5255-7.

Kim YD, et al: Cognitive dysfunction in drug induced parkinsonism (DIP). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011, 53 (2): e222-e226. 10.1016/j.archger.2010.11.025.

Gomez-Esteban JC, et al: Impact of psychiatric symptoms and sleep disorders on the quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s diseas. J Neurol. 2011, 258 (3): 494-499. 10.1007/s00415-010-5786-y.

Weintraub D, et al: Effect of psychiatric and other nonmotor symptoms on disability in Parkinson’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004, 52 (5): 784-788. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52219.x.

Carod-Artal FJ, et al: Anxiety and depression: main determinants of health-related quality of life in Brazilian patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2008, 14 (2): 102-108. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.06.011.

Carod-Artal FJ, Vargas AP, Martinez-Martin P: Determinants of quality of life in Brazilian patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2007, 22 (10): 1408-1415. 10.1002/mds.21408.

Li H, et al: Nonmotor symptoms are independently associated with impaired health-related quality of life in Chinese patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010, 25 (16): 2740-2746. 10.1002/mds.23368.

Qin Z, et al: Health related quality of life in early Parkinson’s disease: impact of motor and non-motor symptoms, results from Chinese levodopa exposed cohort. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009, 15 (10): 767-771. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.05.011.

Slawek J, Derejko M, Lass P: Factors affecting the quality of life of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease–a cross-sectional study in an outpatient clinic attendees. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005, 11 (7): 465-468. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2005.04.006.

Martinez-Martin P, et al: The impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011, 26 (3): 399-406. 10.1002/mds.23462.

Schrag A, Jahanshahi M, Quinn N: What contributes to quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease?. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000, 69 (3): 308-312. 10.1136/jnnp.69.3.308.

Klepac N, et al: Is quality of life in non-demented Parkinson’s disease patients related to cognitive performance? A clinic-based cross-sectional study. Eur J Neurol. 2008, 15 (2): 128-133. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.02011.x.

Schrag A, et al: Health-related quality of life in multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord. 2006, 21 (6): 809-815. 10.1002/mds.20808.

Arlt S, et al: The patient with dementia, the caregiver and the doctor: cognition, depression and quality of life from three perspectives. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008, 23 (6): 604-610. 10.1002/gps.1946.

Watson LC, et al: Perceptions of depression among dementia caregivers: findings from the CATIE-AD trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011, 26 (4): 397-402. 10.1002/gps.2539.

Duberstein PR, et al: Detection of depression in older adults by family and friends: distinguishing mood disorder signals from the noise of personality and everyday life. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23 (4): 634-643. 10.1017/S1041610210001808.

Cepoiu M, et al: Recognition of depression by non-psychiatric physicians–a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2008, 23 (1): 25-36. 10.1007/s11606-007-0428-5.

Docherty JP: Barriers to the diagnosis of depression in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997, 58 (Suppl 1): 5-10.

Wittchen HU, Pittrow D: Prevalence, recognition and management of depression in primary care in Germany: the Depression 2000 study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2002, 17 (Suppl 1): S1-S11.

Parchman ML: Physicians’ recognition of depression. Fam Pract Res J. 1992, 12 (4): 431-438.

Carney PA, et al: How physician communication influences recognition of depression in primary care. J Fam Pract. 1999, 48 (12): 958-964.

Furedi J, et al: The role of symptoms in the recognition of mental health disorders in primary care. Psychosomatics. 2003, 44 (5): 402-406. 10.1176/appi.psy.44.5.402.

Harman JS, et al: The effect of patient and visit characteristics on diagnosis of depression in primary care. J Fam Pract. 2001, 50 (12): 1068-

Luber MP, et al: Diagnosis, treatment, comorbidity, and resource utilization of depressed patients in a general medical practice. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2000, 30 (1): 1-13. 10.2190/YTRY-E86M-G1VC-LC79.

Pentzek M, et al: Apart from nihilism and stigma: what influences general practitioners’ accuracy in identifying incident dementia?. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009, 17 (11): 965-975. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181b2075e.

van Hout H, et al: Are general practitioners able to accurately diagnose dementia and identify Alzheimer’s disease? A comparison with an outpatient memory clinic. Br J Gen Pract. 2000, 50 (453): 311-312.

Valcour VG, et al: The detection of dementia in the primary care setting. Arch Intern Med. 2000, 160 (19): 2964-2968. 10.1001/archinte.160.19.2964.

Chodosh J, et al: Physician recognition of cognitive impairment: evaluating the need for improvement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004, 52 (7): 1051-1059. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52301.x.

O’Connor DW, et al: Do general practitioners miss dementia in elderly patients?. BMJ. 1988, 297 (6656): 1107-1110. 10.1136/bmj.297.6656.1107.

Lopponen M, et al: Diagnosing cognitive impairment and dementia in primary health care – a more active approach is needed. Age Ageing. 2003, 32 (6): 606-612. 10.1093/ageing/afg097.

Crane MK, et al: Brief report: patient cognitive status and the identification and management of depression by primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006, 21 (10): 1042-1044. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00559.x.

Silberman CD, et al: Recognizing depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease: accuracy and specificity of two depression rating scale. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2006, 64(2B): 407-411.

Tumas V, et al: The accuracy of diagnosis of major depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a comparative study among the UPDRS, the geriatric depression scale and the Beck depression inventory. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008, 66(2A): 6-152.

Leentjens AF, et al: The validity of the Hamilton and Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scales as screening and diagnostic tools for depression in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000, 15 (7): 644-649. 10.1002/1099-1166(200007)15:7<644::AID-GPS167>3.0.CO;2-L.

Shulman LM, et al: Non-recognition of depression and other non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002, 8 (3): 193-197. 10.1016/S1353-8020(01)00015-3.

Burn DJ: Beyond the iron mask: towards better recognition and treatment of depression associated with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2002, 17 (3): 445-454. 10.1002/mds.10114.

Gallagher DA, Lees AJ, Schrag A: What are the most important nonmotor symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease and are we missing them?. Mov Disord. 2010, 25 (15): 2493-2500. 10.1002/mds.23394.

Vlaar AM, et al: Protocol of a prospective study on the diagnostic value of transcranial duplex scanning of the substantia nigra in patients with parkinsonian symptoms. BMC Neurol. 2007, 7: 28-10.1186/1471-2377-7-28.

Reijnders JS, Lousberg R, Leentjens AF: Assessment of depression in Parkinson’s disease: the contribution of somatic symptoms to the clinimetric performance of the Hamilton and Montgomery-Asberg rating scales. J Psychosom Res. 2010, 68 (6): 561-565. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.006.

Schrag A, et al: Depression rating scales in Parkinson’s disease: critique and recommendations. Mov Disord. 2007, 22 (8): 1077-1092. 10.1002/mds.21333.

Furukawa TA: Assessment of mood: guides for clinicians. J Psychosom Res. 2010, 68 (6): 581-589. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.05.003.

Furukawa TA, et al: Evidence-based guidelines for interpretation of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007, 27 (5): 531-534. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31814f30b1.

Kulisevsky J, Pagonabarraga J: Cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: tools for diagnosis and assessment. Mov Disord. 2009, 24 (8): 1103-1110. 10.1002/mds.22506.

Carod-Artal FJ, et al: Psychometric attributes of the SCOPA-COG Brazilian version. Mov Disord. 2008, 23 (1): 81-87. 10.1002/mds.21769.

Lemke MR: Depressive symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2008, 15 (Suppl 1): 21-25.

Aarsland D, Kurz MW: The epidemiology of dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2010, 20 (3): 633-639. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00369.x.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/12/37/prepub

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by the “Stichting Internationaal Parkinson Fonds”. We thank consultant neurologists Bert Anten, Fred Vreeling, Annemarie Vlaar, and Ania Winogrodzka for their helpful cooperation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

Both authors have contributed to all of the following: 1. Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; 2. Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; 3. Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and Critique. Full financial disclosure for the previous 12 months: Bouwmans: Stichting Internationaal Parkinson Fonds. Weber: Stichting Internationaal Parkinson Fonds. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bouwmans, A.E., Weber, W.E. Neurologists’ diagnostic accuracy of depression and cognitive problems in patients with parkinsonism. BMC Neurol 12, 37 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-12-37

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-12-37