Abstract

Background

The polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a common endocrine disorder in women of child-bearing age, mainly characterised by chronic anovulation and hyperandrogenism, is often associated with insulin resistance (IR) and obesity. Its etiology and the role of IR and obesity in PCOS are not fully understood. We examined the influence of validated genetic variants conferring susceptibility to obesity and/or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) on metabolic and PCOS-specific traits in patients with PCOS.

Methods

We conducted an association study in 386 patients with PCOS (defined by the Rotterdam-criteria) using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in or in proximity to the fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO), insulin-induced gene-2 (INSIG2), transcription factor 7-like 2 gene (TCF7L2) and melanocortin 4 receptor gene (MC4R). To compare the effect of FTO obesity risk alleles on BMI in patients with PCOS to unselected females of the same age range we genotyped 1,971 females from the population-based KORA-S4 study (Kooperative Gesundheitsforschung im Raum Augsburg, Survey 4).

Results

The FTO risk allele was associated with IR traits and measures of increased body weight. In addition, the TCF7L2 SNP was associated with body weight traits. For the SNPs in the vicinity of INSIG2 and MC4R and for the other examined phenotypes there was no evidence for an association. In PCOS the observed per risk allele effect of FTO intron 1 SNP rs9939609 on BMI was +1.56 kg/m2, whereas it was +0.46 kg/m2 in females of the same age range from the general population as shown previously.

Conclusion

The stronger effect on body weight of the FTO SNP in PCOS might well have implications for the etiology of the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrinopathy affecting about 6% of women of child-bearing age [1]. It is classically characterised by chronic anovulation, hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovarian morphology on ultrasonography [2]. In addition, a close relationship exists between obesity, insulin resistance (IR) and PCOS [3, 4]. Despite a growing body of evidence demonstrating a substantial heritability of PCOS and the intrinsic impact of IR on the development of PCOS, its etiology and underlying pathophysiology still remains elusive.

To date, multiple genetic studies in PCOS have been performed examining genes coding for enzymes of steroid biosynthesis like CYP11, CYP17, CYP19, androgen receptor, insulin, insulin receptor and enzymes in the post-receptor signal cascade of insulin. However, a variant contributing substantially to the development of the PCOS phenotype was not detected [5–8]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) offer a new approach to gene discovery unbiased with regard to the presumed function of causal variants. Up to one million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) that are distributed evenly across the whole genome are commonly used for this approach. In the field of human body weight regulation these studies already had a major impact on the identification of relevant polygenes. For instance, common variants in the fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO) predispose to an elevated body mass index (BMI) with an increase of 0.36 kg/m2 BMI units per risk allele. Homozygous risk allele carriers weighed about three kilograms more and had 1.67-fold higher odds for obesity compared to adults not inheriting the risk allele [9]. This robust association was also detectable in the first GWAS for early onset extreme obesity [10]. With regard to insulin sensitivity, a recent British study in healthy adults indicated an association between polymorphisms of the FTO gene and a decrease in insulin sensitivity, which was presumably BMI mediated [11]. Barber et al. additionally demonstrated an association between PCOS status and FTO obesity risk SNPs in a case-control study [12]. Using a similar approach, Attaoua et al. discussed the potential role of FTO variants for the glucose intolerance component of the metabolic syndrome in patients with PCOS [13]. Association with increased risk of obesity has also been demonstrated for SNP rs7566605 located ~10 kb upstream of the insulin-induced gene-2 (INSIG2), which was detected in the first population-based GWAS for body weight [14]. Results concerning the influence of this SNP on obesity risk are conflicting, as not all studies detected the association with obesity [15–18]. However, in a meta-analysis of case-control and family-based approaches comprising about 17,000 individuals a marginal effect of rs7566605 on obesity was still present [19]. Recently, Reinehr et al. showed a lower success rate of a lifestyle intervention for obese children homozygous for the risk allele C [20]. A solidly validated gene for type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the transcription factor 7-like 2 gene (TCF7L2). Identified via a conventional genome wide linkage scan for T2DM and subsequent fine mapping [21], it had convincingly been confirmed in numerous studies including GWAS [22–24]. The gene codes for a stimulating regulator of proglucagon gene expression [25]. The proglucagon gene is post-translationally processed to produce GLP-1, a stimulator of insulin secretion and biosynthesis and it is an inhibitor of glucagon release [26]. GWAS reported association of a SNP in TCF7L2 with T2DM and IR in Caucasians [21, 27, 28] but a negative association to body weight [21, 28–30]. In PCOS patients, using a sample size and design similar to their FTO study [12], a case-control comparison did not provide evidence for an association of TCF7L2 variants with disease status [31]. A further (negative) correlation to weight status was robustly found for a non-synonymous polymorphism Val103Ile in the melanocortin-4 receptor gene (MC4R) [32–34]. Interestingly, another genetic locus in the vicinity of the MC4R was recently also detected by a large-scaled GWAS [35]. The respective SNP was associated with obesity; it is located 188 downstream of the MC4R; its effect is presumably exerted by an influence on the expression of the gene. Additionally, another SNP near the previously described one, was shown to be associated with waist circumference and insulin resistance [36].

Given the high prevalence of obesity in PCOS and the compelling evidence for a substantial genetic background of both PCOS and obesity, known obesity susceptibility genes emerge as eligible candidates that might also be involved in the development of PCOS. Therefore we examined the influence of the described genetic variants on obesity and other endophenotypes in patients with PCOS. We considered polymorphisms in or near FTO, INSIG2, TCF7L2 and MC4R that are all well supported by large data collections of GWAS or meta-analyses for our analyses in patients with PCOS.

Methods

Patient Recruitment

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the University of Essen and Munich. All subjects gave written informed consent. The study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consecutive, currently untreated patients with PCOS (n = 386) were recruited between 2/2001 and 1/2007 at the outpatient clinic of the Department of Endocrinology and Division of Laboratory Research, University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany. Some patients were also attracted by the PCOS homepage of the clinic http://www.pco-syndrom.de. PCOS was defined according to the 2003 Rotterdam criteria, so diagnosis of PCOS was established, if two of the three criteria chronic anovulation, clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovaries (PCO) were fulfilled and other pituitary, adrenal or ovarian diseases could be excluded [2].

Clinical Characterization of Patients

Participants were carefully characterized with regard to medical history, clinical and socio-demographic variables using questionnaires, interview, and physical examinations, as previously described in detail [37]. Free androgen index (FAI) was calculated as total testosterone [nmol/l] × 100/SHBG [nmol/l]. Bioavailable testosterone concentration was calculated based on measured testosterone, SHBG and albumin levels [38]. Variables of IR and β-cell function were evaluated using a 3-h oral glucose tolerance test. After an overnight fast of 12 h patients ingested 75 g glucose and had their glucose and insulin levels determined at baseline and at 30, 60, 90, 120 and 180 min. IR was defined by the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) model [39] and hyperinsulinemia by calculating the area under the curve of insulin response (AUCI).

Females from the population-based sample (KORA-S4)

KORA (Kooperative Gesundheitsforschung im Raum Augsburg, Survey 4; 'Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg') is an epidemiological study group including 4,261 German adults representative of the population within the age range of 25-74 years in the city and region of Augsburg (Bavaria, Germany); probands were recruited between 1999-2001 [40]. FTO (rs9939609) genotypes as well as phenotype data were available for 1,971 females (mean BMI 26.96 ± 5.28 kg/m2, mean age 48.85 ± 13.69 years).

Biochemical Analyses

Automated chemiluminescence immunoassay systems were used for the determination of LH, FSH, TSH, testosterone, estradiol, cortisol, free thyroxine, prolactin, blood glucose (ADVIA Centaur, Siemens, Germany), ACTH, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, androstenedione, sex hormone-binding globulin, insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IMMULITE 2000, Siemens, Germany). Measurement of blood glucose was performed by photometric determination (ADVIA 2400, Siemens, Germany). Intraassay variation was < 5% and interassay variation was < 8% for all measured variables. 17-hydroxyprogesterone was measured by the BIOSOURCE 17-alpha-OH-RIA-CT kit (Biosource International, California, USA) (analytical sensitivity 0.02 ng/ml) provided by IBL Hamburg (IBL, Gesellschaft für Immunchemie und Immunbiologie, Hamburg, Germany). The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 5.6 and 7.2% respectively. Except for amenorrhoic women, all laboratory variables were determined in the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from EDTA-anticoagulated blood using standard procedures. Genotyping of FTO SNP rs9939609 was performed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) analysis of allele-dependent primer extension products as described elsewhere [41]. For MC4R Val103Ile (rs2229616), DNA samples were genotyped as described previously. MC4R SNPs rs17782313 and rs12970134 were genotyped using TaqMan® assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). All TaqMan® probes and primers were purchased from Applied Biosystems (assays on demand; http://www.appliedbiosystems.com). For the TCF7L2 rs79031746, genotyping was performed by allele-specific PCR reactions (tetra-ARMS PCR; primers were as follows: (forward inner primer (C allele): 5'-TAGAGAGCTAAGCACTTTTTAGAGAC-3'; reverse inner primer (T allele): 5'-CTCATACGGCAATTAAATTATAGAA-3'; forward outer primer: 5'-AATTTTTTCACATGTGAAGACATAC-3'; reverse outer primer: 5'-AAGAGATGAAATGTAGCAGTGAAG-3'. The C allele is detected by a 202 bp amplicon and the T allele by a 272 bp amplicon. The product size of two outer primers is 424 bp.

Genotyping of INSIG2 SNP rs7566605 was carried out by PCR-RFLP with Bsp143I (digests the C-allele; primers: 5'-TGAAGTTGATCTAATGTTCTCTCTCC-3' and 5'-AAACCAAGGGAATCGAGAGC-3'). PCR products were run on ethidium bromide-stained 2.5% agarose gels. Positive controls for the variant alleles and a negative control (water) were run on each gel. To validate the genotypes, allele determinations were rated independently by at least two experienced individuals. Discrepancies were resolved unambiguously either by reaching consensus or by retyping. Missings were retyped.

Statistical Analyses

All genotype distributions were tested for deviations from Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using the PLINK software (Version 1.06 [42]) and no evidence for such deviations was detected (all p >> 0.4). All endophenotypes were analysed by either linear or logistic regression analyses using age in years as a covariate. Each SNP was analyzed under an (log-) additive genetic model, except for MC4R (rs2229616), where a dominant mode of inheritance was assumed. Nominal two-sided p-values, genetic effect sizes estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the estimates were derived. To address, the problem of testing multiple hypotheses, we also derived multiplicity-adjusted p-values for our strongest association signals (see Table three) using a method of described in [43]. As secondary analyses, robust linear regressions were used for the comparison of the PCOS patients with the population-based females and for an exploration of joint or interaction effects of FTO and TCF7L2 SNPs; model assumptions were checked graphically.

Power calculations were done with the software QUANTO (Version 1.2.3, http://hydra.usc.edu/gxe). 386 PCOS patients were estimated to yield a power > 0.80 to detect a standardized additive genetic effect size of 0.5 (α = 0.05; two-sided) assuming a minor allele frequency (MAF) of 5% and a standard normally distributed phenotype. For larger MAFs like 46.2%, smaller effect sizes of 0.2 will be detectable with a similar power. For comparison, standardized effect sizes like 0.1 have for example been reported for markers in FTO or TCF7L2 in unselected or control individuals for quantitative traits [9, 44]. A standardized effect size of e.g. 0.1 in the additive genetic model implies that the distributions for the three genotypes are shifted by 1/10 of as standard deviation for the respective quantitative trait. Thus, except for rs2229616 with its low allele frequency (1.6%, Table 1), the study was well powered to detect strong to moderate genetic effects which might be present in our highly selected sample of PCOS patients.

Results

The clinical and phenotypical characteristics of the investigated patients with PCOS as well as the estimated minor allele frequencies (MAFs) are given in Table 1. Table 1 also includes subgroup distributions according to the Rotterdam criteria (hyperandrogenism (HA), oligo-anovulation (OA) and polycystic ovaries (PCO)) as metabolic differences between theses subgroups have been described [45–48].

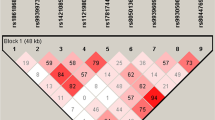

Exploration of associations between genotypes and metabolic/obesity related variables in patients with PCOS revealed some evidence for an association of variants in FTO and TCF7L2, whereas no indication of association was observable for SNPs in INSIG2 and MC4R (see Table 2). We estimated that each risk allele of the polymorphism rs9939609 of FTO increased the body weight by ~4.6 kg, whereas the BMI was increased by ~1.6 kg/m2 and the waist circumference increased by ~3.5 cm. Of note, the effect size of rs9939609 on BMI in PCOS was larger than in unselected females from the general population in the same age range (see Figure 1). For the TCF7L2 polymorphism rs7903146 the per risk allele effect was ~4.2 kg body weight, ~1.4 kg/m2 BMI and ~3.4 cm waist circumference, respectively (for details see Table 2). There was no evidence for a potentially strong interaction or a correlation between the FTO (adjusted effect 1.35 kg/m2 in robust linear regression) and the TCF7L2 locus (adjusted effect 1.45 kg/m2). Moreover, FTO variant rs9939609 was associated with variables of insulin resistance (see Table 3). As an example, the estimated per risk allele effect was 3.25 mU/l for fasting insulin, which changed to 1.88 mU/l (95%CI 0.22 mU/l; 3.54 mU/l, p-value = 0.03), if BMI was added as a covariate to the regression model. Thus, even after correcting for BMI, a genetic effect of rs9939609 on fasting insulin levels was observed. By contrast, there was no evidence for an association of SNPs in INSIG2, TCF7L2 and MC4R with variables of insulin resistance (for details see Table 3).

Relationship between the FTO SNP rs9939609, BMI and age in females for the general population and in patients with PCOS. Each dot represents one observation; the lines are derived from a robust linear regression on the complete data set of females with BMI as outcome and age (linear), group, genotype in the logadditive model and the interaction group x genotype as predictors.

Finally, we investigated the relationship between the variants and PCOS specific characteristics (for details see Tables 4 and 5). There was no association to chronic anovulation, hirsutism, acne, alopecia or androgen levels for any of the variants. Interestingly, we observed that the obesity risk allele A of the FTO variant rs9939609 was less frequently observed in patients with polycystic ovarian morphology (PCO) compared to PCOS patients without PCO (OR = 0.57, 95%, CI 0.36;0.88, p-value = 0.01) and even after correction for BMI this relationship was still present (OR = 0.60, 95%CI 0.37;0.93, p-value = 0.02).

Discussion

The influence of FTO intron 1 variation on body weight related phenotypes in patients with PCOS is underscored. In population-based GWAS the estimated per risk allele effect ranged between 0.36 kg/m2 [9] and 0.66 kg/m2 [49] for statistical models with a slightly different set of covariates. In our PCOS sample, we estimated an average effect of the FTO risk allele of 1.56 kg/m2 (95%CI 0.34 kg/m2; 2.78 kg/m2) including age as a quantitative covariate. Thus, the impact of the FTO variants on BMI is larger in PCOS patients than in the general population with an average effect of the FTO risk allele of 0.46 kg/m2 (95%CI 0.17 kg/m2; 0.75 kg/m2) as shown in Figure 1. Of note, our finding is surprisingly similar to those of other studies [12, 50]. Barber et al. report a per risk allele effect of 1.1 kg/m2 (95%CI -0.9 kg/m2; 3.2 kg/m2) in their PCOS cases and only 0.5 kg/m2 (95%CI -0.1 kg/m2; 1.3 kg/m2) in their controls [12]. Moreover, this study is, to our knowledge, the first to describe a correlation between FTO rs9939609 and insulin resistance or hyperinsulinemia in PCOS patients reflected in fasting insulin, HOMA-IR as well as in AUCI levels After strictly controlling for the multiple statistical tests performed here (multiple phenotypes and multiple SNPs) the adjusted p-value for FTO rs9939609 and fasting insulin was 0.062 and the related effect, though weaker, was still present even after statistically correcting for BMI. Other study groups could not demonstrate an association between FTO and IR in obese and T2DM patients, respectively [51, 52]. In PCOS, FTO variation seems to be a key marker for IR, either directly i.e. to some degree independent of BMI/obesity or secondary due to its impact on body weight which in turn has an impact on glucose intolerance and diabetes. Barber et al. at first demonstrated an association between FTO and PCOS status and hypothesized a mediation of this association by adiposity. However, in this British sample, no IR data were available. In a French sample FTO was associated with both glucose intolerance and metabolic syndrome [13] without finding an association to IR. The greater effect on BMI and association to IR in PCOS possibly reflects a pathogenetic function of the FTO gene in the development of PCOS. This study and the data from Barber et al. demonstrated, that the FTO gene does not influence any of the PCOS defining traits neither directly nor indirectly via an effect on obesity or IR. In this German cohort, it is even less frequently associated with PCO. In case of a pathogenetic role of FTO in PCOS, it seems to be limited to determine only the metabolic phenotype.

As second strongest signal, we found association between the T2DM susceptibility gene TCF7L2 risk allele and obesity related traits in patients with PCOS. The TCF7L2 obesity association was stochastically independent of the FTO association if assessed in a multiple regression analysis. While some did not find an influence on body weight [29, 30, 53–56], others have reported analogous associations of TCF7L2 and obesity related traits [28, 43, 57]. Despite possible effects related to differences in ascertainment schemes, multiple explanations for this conflicting findings are possible [57]. One possible explanation by Cauchi and collegues [43] is that the risk for T2DM related to TCF7L2 seems to be modulated by the obesity status of an individual with stronger effects in the obese. It is possible that our study picked-up this BMI-related effect of TCF7L2. As we observed no evidence for an association of TCF7L2 with IR or other PCOS specific symptoms, common variants of TCF7L2 most likely influence T2DM susceptibility through impairment of insulin secretion rather than IR [56, 58]. Interestingly, this observation is consistent with the PCOS data of Barber et al. [12] who failed to detect association of TCF7L2 variation but who do not report on the genotype dependent BMI-distribution.

Finally, our data on rs7566605 located ~10 kb upstream of INSIG2 and on markers in proximity to MC4R provided no evidence for an involvement in the development of PCOS or related endophenotypes.

Conclusion

In summary, we explored (mainly) GWAS-derived candidate gene markers for obesity and T2DM in patients with PCOS. We show that the impact of INSIG2, TCF7L2 and MC4R SNPs on multiple endophenotypes might either be rather weak or not present at all. For genetic variation in intron 1 of FTO we provide evidence for associations to metabolic aspects of PCOS with some emphasis on IR. Interestingly, the estimated effect on obesity seems to be larger than the effect derived from population-based samples. This stronger effect might well have implications for the etiology of the disease requiring focussed functional studies.

References

Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO: The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 89: 2745-2749. 10.1210/jc.2003-032046.

Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004, 81: 19-25.

Kiddy DS, Hamilton-Fairley D, Bush A, Short F, Anyaoku V, Reed MJ, Franks S: Improvement in endocrine and ovarian function during dietary treatment of obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1992, 36: 105-111. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02909.x.

Dunaif A, Segal KR, Futterweit W, Dobrjansky A: Profound peripheral insulin resistance, independent of obesity, in polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes. 1989, 38: 1165-1174. 10.2337/diabetes.38.9.1165.

Talbot JA, Bicknell EJ, Rajkhowa M, Krook A, O'Rahilly S, Clayton RN: Molecular scanning of the insulin receptor gene in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996, 81: 1979-1983. 10.1210/jc.81.5.1979.

Dunaif A, Wu X, Lee A, Diamanti-Kandarakis E: Defects in insulin receptor signaling in vivo in the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001, 281: E392-399.

Legro RS, Strauss JF: Molecular progress in infertility: polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2002, 78: 569-576. 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03275-2.

Stewart DR, Dombroski BA, Urbanek M, Ankener W, Ewens KG, Wood JR, Legro RS, Strauss JF, Dunaif A, Spielman RS: Fine mapping of genetic susceptibility to polycystic ovary syndrome on chromosome 19p13.2 and tests for regulatory activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006, 91: 4112-4117. 10.1210/jc.2006-0951.

Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, Zeggini E, Freathy RM, Lindgren CM, Perry JR, Elliott KS, Lango H, Rayner NW, et al: A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007, 316: 889-894. 10.1126/science.1141634.

Hinney A, Nguyen TT, Scherag A, Friedel S, Bronner G, Muller TD, Grallert H, Illig T, Wichmann HE, Rief W, et al: Genome wide association (GWA) study for early onset extreme obesity supports the role of fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO) variants. PLoS ONE. 2007, 2: e1361-10.1371/journal.pone.0001361.

Pascoe L, Tura A, Patel SK, Ibrahim IM, Ferrannini E, Zeggini E, Weedon MN, Mari A, Hattersley AT, McCarthy MI, et al: Common variants of the novel type 2 diabetes genes CDKAL1 and HHEX/IDE are associated with decreased pancreatic beta-cell function. Diabetes. 2007, 56: 3101-3104. 10.2337/db07-0634.

Barber TM, Bennett AJ, Groves CJ, Sovio U, Ruokonen A, Martikainen H, Pouta A, Hartikainen AL, Elliott P, Lindgren CM, et al: Association of variants in the fat mass and obesity associated (FTO) gene with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetologia. 2008, 51: 1153-1158. 10.1007/s00125-008-1028-6.

Attaoua R, Ait El Mkadem S, Radian S, Fica S, Hanzu F, Albu A, Gheorghiu M, Coculescu M, Grigorescu F: FTO gene associates to metabolic syndrome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008, 373: 230-234. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.039.

Herbert A, Gerry NP, McQueen MB, Heid IM, Pfeufer A, Illig T, Wichmann HE, Meitinger T, Hunter D, Hu FB, et al: A common genetic variant is associated with adult and childhood obesity. Science. 2006, 312: 279-283. 10.1126/science.1124779.

Kumar J, Sunkishala RR, Karthikeyan G, Sengupta S: The common genetic variant upstream of INSIG2 gene is not associated with obesity in Indian population. Clin Genet. 2007, 71: 415-418. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00795.x.

Loos RJ, Barroso I, O'Rahilly S, Wareham NJ: Comment on "A common genetic variant is associated with adult and childhood obesity". Science. 2007, 315: 187-10.1126/science.1130012.

Dina C, Meyre D, Samson C, Tichet J, Marre M, Jouret B, Charles MA, Balkau B, Froguel P: Comment on "A common genetic variant is associated with adult and childhood obesity". Science. 2007, 315: 187-10.1126/science.1129402.

Rosskopf D, Bornhorst A, Rimmbach C, Schwahn C, Kayser A, Kruger A, Tessmann G, Geissler I, Kroemer HK, Volzke H: Comment on "A common genetic variant is associated with adult and childhood obesity". Science. 2007, 315: 187-10.1126/science.1130571.

Lyon HN, Emilsson V, Hinney A, Heid IM, Lasky-Su J, Zhu X, Thorleifsson G, Gunnarsdottir S, Walters GB, Thorsteinsdottir U, et al: The association of a SNP upstream of INSIG2 with body mass index is reproduced in several but not all cohorts. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3: e61-10.1371/journal.pgen.0030061.

Reinehr T, Hinney A, Nguyen TT, Hebebrand J: Evidence of an influence of a polymorphism near the INSIG2 on weight loss during a lifestyle intervention in obese children and adolescents. Diabetes. 2008, 57: 623-626. 10.2337/db07-0408.

Grant SF, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, Benediktsson R, Manolescu A, Sainz J, Helgason A, Stefansson H, Emilsson V, Helgadottir A, et al: Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2006, 38: 320-323. 10.1038/ng1732.

Meigs JB, Manning AK, Fox CS, Florez JC, Liu C, Cupples LA, Dupuis J: Genome-wide association with diabetes-related traits in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet. 2007, 8 (Suppl 1): S16-10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S16.

Lyssenko V, Lupi R, Marchetti P, Del Guerra S, Orho-Melander M, Almgren P, Sjogren M, Ling C, Eriksson KF, Lethagen AL, et al: Mechanisms by which common variants in the TCF7L2 gene increase risk of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2007, 117: 2155-2163. 10.1172/JCI30706.

Palmer ND, Lehtinen AB, Langefeld CD, Campbell JK, Haffner SM, Norris JM, Bergman RN, Goodarzi MO, Rotter JI, Bowden DW: Association of TCF7L2 gene polymorphisms with reduced acute insulin response in Hispanic Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008, 93: 304-309. 10.1210/jc.2007-1225.

Yi F, Brubaker PL, Jin T: TCF-4 mediates cell type-specific regulation of proglucagon gene expression by beta-catenin and glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280: 1457-1464. 10.1074/jbc.M411487200.

Deacon CF: Therapeutic strategies based on glucagon-like peptide 1. Diabetes. 2004, 53: 2181-2189. 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2181.

Sladek R, Rocheleau G, Rung J, Dina C, Shen L, Serre D, Boutin P, Vincent D, Belisle A, Hadjadj S, et al: A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007, 445: 881-885. 10.1038/nature05616.

Helgason A, Palsson S, Thorleifsson G, Grant SF, Emilsson V, Gunnarsdottir S, Adeyemo A, Chen Y, Chen G, Reynisdottir I, et al: Refining the impact of TCF7L2 gene variants on type 2 diabetes and adaptive evolution. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 218-225. 10.1038/ng1960.

Saxena R, Gianniny L, Burtt NP, Lyssenko V, Giuducci C, Sjogren M, Florez JC, Almgren P, Isomaa B, Orho-Melander M, et al: Common single nucleotide polymorphisms in TCF7L2 are reproducibly associated with type 2 diabetes and reduce the insulin response to glucose in nondiabetic individuals. Diabetes. 2006, 55: 2890-2895. 10.2337/db06-0381.

Cauchi S, Meyre D, Dina C, Choquet H, Samson C, Gallina S, Balkau B, Charpentier G, Pattou F, Stetsyuk V, et al: Transcription factor TCF7L2 genetic study in the French population: expression in human beta-cells and adipose tissue and strong association with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006, 55: 2903-2908. 10.2337/db06-0474.

Barber TM, Bennett AJ, Groves CJ, Sovio U, Ruokonen A, Martikainen H, Pouta A, Hartikainen AL, Elliott P, Wass JA, et al: Disparate genetic influences on polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and type 2 diabetes revealed by a lack of association between common variants within the TCF7L2 gene and PCOS. Diabetologia. 2007, 50: 2318-2322. 10.1007/s00125-007-0804-z.

Geller F, Reichwald K, Dempfle A, Illig T, Vollmert C, Herpertz S, Siffert W, Platzer M, Hess C, Gudermann T, et al: Melanocortin-4 receptor gene variant I103 is negatively associated with obesity. Am J Hum Genet. 2004, 74: 572-581. 10.1086/382490.

Heid IM, Vollmert C, Hinney A, Doring A, Geller F, Lowel H, Wichmann HE, Illig T, Hebebrand J, Kronenberg F: Association of the 103I MC4R allele with decreased body mass in 7937 participants of two population based surveys. J Med Genet. 2005, 42: e21-10.1136/jmg.2004.027011.

Young EH, Wareham NJ, Farooqi S, Hinney A, Hebebrand J, Scherag A, O'Rahilly S, Barroso I, Sandhu MS: The V103I polymorphism of the MC4R gene and obesity: population based studies and meta-analysis of 29 563 individuals. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007, 31: 1437-1441. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803609.

Loos RJ, Lindgren CM, Li S, Wheeler E, Zhao JH, Prokopenko I, Inouye M, Freathy RM, Attwood AP, Beckmann JS, et al: Common variants near MC4R are associated with fat mass, weight and risk of obesity. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 768-775. 10.1038/ng.140.

Chambers JC, Elliott P, Zabaneh D, Zhang W, Li Y, Froguel P, Balding D, Scott J, Kooner JS: Common genetic variation near MC4R is associated with waist circumference and insulin resistance. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 716-718. 10.1038/ng.156.

Tan S, Hahn S, Benson S, Dietz T, Lahner H, Moeller LC, Schmidt M, Elsenbruch S, Kimmig R, Mann K, Janssen OE: Metformin improves polycystic ovary syndrome symptoms irrespective of pre-treatment insulin resistance. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007, 157: 669-676. 10.1530/EJE-07-0294.

Vermeulen A, Verdonck L, Kaufman JM: A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999, 84: 3666-3672. 10.1210/jc.84.10.3666.

Hermans MP, Levy JC, Morris RJ, Turner RC: Comparison of tests of beta-cell function across a range of glucose tolerance from normal to diabetes. Diabetes. 1999, 48: 1779-1786. 10.2337/diabetes.48.9.1779.

Holle R, Happich M, Lowel H, Wichmann HE: KORA--a research platform for population based health research. Gesundheitswesen. 2005, 67 (Suppl 1): S19-25. 10.1055/s-2005-858235.

Vollmert C, Windl O, Xiang W, Rosenberger A, Zerr I, Wichmann HE, Bickeboller H, Illig T, Kretzschmar HA: Significant association of a M129V independent polymorphism in the 5' UTR of the PRNP gene with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in a large German case-control study. J Med Genet. 2006, 43: e53-10.1136/jmg.2006.040931.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC: PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007, 81: 559-575. 10.1086/519795.

Cauchi S, Nead KT, Choquet H, Horber F, Potoczna N, Balkau B, Marre M, Charpentier G, Froguel P, Meyre D: The genetic susceptibility to type 2 diabetes may be modulated by obesity status: implications for association studies. BMC Med Genet. 2008, 9: 45-10.1186/1471-2350-9-45.

Stolerman ES, Manning AK, McAteer JB, Fox CS, Dupuis J, Meigs JB, Florez JC: TCF7L2 variants are associated with increased proinsulin/insulin ratios but not obesity traits in the Framingham Heart Study. Diabetologia. 2009, 52: 614-620. 10.1007/s00125-009-1266-2.

Rizzo M, Berneis K, Hersberger M, Pepe I, Di Fede G, Rini GB, Spinas GA, Carmina E: Milder forms of atherogenic dyslipidemia in ovulatory versus anovulatory polycystic ovary syndrome phenotype. Hum Reprod. 2009, 24: 2286-2292. 10.1093/humrep/dep121.

Kauffman RP, Baker TE, Baker VM, DiMarino P, Castracane VD: Endocrine and metabolic differences among phenotypic expressions of polycystic ovary syndrome according to the 2003 Rotterdam consensus criteria. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008, 198: 670-10.1016/j.ajog.2008.01.037.

Barber TM, Wass JA, McCarthy MI, Franks S: Metabolic characteristics of women with polycystic ovaries and oligo-amenorrhoea but normal androgen levels: implications for the management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007, 66: 513-517.

Dewailly D, Catteau-Jonard S, Reyss AC, Leroy M, Pigny P: Oligoanovulation with polycystic ovaries but not overt hyperandrogenism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006, 91: 3922-3927. 10.1210/jc.2006-1054.

Scuteri A, Sanna S, Chen WM, Uda M, Albai G, Strait J, Najjar S, Nagaraja R, Orru M, Usala G, et al: Genome-wide association scan shows genetic variants in the FTO gene are associated with obesity-related traits. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3: e115-10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115.

Kowalska I, Malecki MT, Straczkowski M, Skupien J, Karczewska-Kupczewska M, Nikolajuk A, Szopa M, Adamska A, Wawrusiewicz-Kurylonek N, Wolczynski S, et al: The FTO gene modifies weight, fat mass and insulin sensitivity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, where its role may be larger than in other phenotypes. Diabetes Metab. 2009, 35 (4): 328-31. 10.1016/j.diabet.2009.03.004.

Horikoshi M, Hara K, Ito C, Shojima N, Nagai R, Ueki K, Froguel P, Kadowaki T: Variations in the HHEX gene are associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes in the Japanese population. Diabetologia. 2007, 50: 2461-2466. 10.1007/s00125-007-0827-5.

Wahlen K, Sjolin E, Hoffstedt J: The common rs9939609 gene variant of the fat mass- and obesity-associated gene FTO is related to fat cell lipolysis. J Lipid Res. 2008, 49: 607-611. 10.1194/jlr.M700448-JLR200.

Marzi C, Huth C, Kolz M, Grallert H, Meisinger C, Wichmann HE, Rathmann W, Herder C, Illig T: Variants of the transcription factor 7-like 2 gene (TCF7L2) are strongly associated with type 2 diabetes but not with the metabolic syndrome in the MONICA/KORA surveys. Horm Metab Res. 2007, 39: 46-52. 10.1055/s-2007-957345.

Melzer D, Murray A, Hurst AJ, Weedon MN, Bandinelli S, Corsi AM, Ferrucci L, Paolisso G, Guralnik JM, Frayling TM: Effects of the diabetes linked TCF7L2 polymorphism in a representative older population. BMC Med. 2006, 4: 34-10.1186/1741-7015-4-34.

Chandak GR, Janipalli CS, Bhaskar S, Kulkarni SR, Mohankrishna P, Hattersley AT, Frayling TM, Yajnik CS: Common variants in the TCF7L2 gene are strongly associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Indian population. Diabetologia. 2007, 50: 63-67. 10.1007/s00125-006-0502-2.

Loos RJ, Franks PW, Francis RW, Barroso I, Gribble FM, Savage DB, Ong KK, O'Rahilly S, Wareham NJ: TCF7L2 polymorphisms modulate proinsulin levels and beta-cell function in a British Europid population. Diabetes. 2007, 56: 1943-1947. 10.2337/db07-0055.

Florez JC, Jablonski KA, Bayley N, Pollin TI, de Bakker PI, Shuldiner AR, Knowler WC, Nathan DM, Altshuler D: TCF7L2 polymorphisms and progression to diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355: 241-250. 10.1056/NEJMoa062418.

Pascoe L, Frayling TM, Weedon MN, Mari A, Tura A, Ferrannini E, Walker M: Beta cell glucose sensitivity is decreased by 39% in non-diabetic individuals carrying multiple diabetes-risk alleles compared with those with no risk alleles. Diabetologia. 2008, 51: 1989-1992. 10.1007/s00125-008-1124-7.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/11/12/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank the probands for their participation.

This work was supported by grants from the Bundesministerium fuer Bildung und Forschung (NGFNPLUS01GS0820), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (HE 1446/4-2, HE 1446/9-1) and the European Union (FP6 LSHMCT-2003-503041).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

ST contributed substantially to conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. AS contributed substantially to conception and design of the study, analysis of data, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. OEJ, SH, HL, TD, RK and KM contributed to acquisition of data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. SS and CIGV carried out the molecular genetic studies for polymorphisms of TCF7L2, INSIG2 and MC4R and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. HG and TI contributed to acquisition of data, carried out the molecular genetic studies for polymorphisms of FTO and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. JH and AH contributed substantially to conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data and were involved in drafting the manuscript and haves given final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, S., Scherag, A., Janssen, O.E. et al. Large effects on body mass index and insulin resistance of fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO) variants in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). BMC Med Genet 11, 12 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-11-12

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-11-12