Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Novel type 2 diabetes-susceptibility loci have been identified with evidence that individually they mediate the increased diabetes risk through altered pancreatic beta cell function. The aim of this study was to test the cumulative effects of diabetes-risk alleles on measures of beta cell function in non-diabetic individuals.

Methods

A total of 1,211 non-diabetic individuals underwent metabolic assessment including an OGTT, from which measures of beta cell function were derived. Individuals were genotyped at each of the risk loci and then classified according to the total number of risk alleles that they carried. Initial analysis focused on CDKAL1, HHEX/IDE and TCF7L2 loci, which were individually associated with a decrease in beta cell function in our cohort. Risk alleles for CDKN2A/B, SLC30A8, IGF2BP2 and KCNJ11 loci were subsequently included into the analysis.

Results

The diabetes-risk alleles for CDKAL1, HHEX/IDE and TCF7L2 showed an additive model of association with measures of beta cell function. Beta cell glucose sensitivity was decreased by 39% in those individuals with five or more risk alleles compared with those individuals with no risk alleles (geometric mean [SEM]: 84 [1.07] vs 137 [1.11] pmol min−1 m−2 (mmol/l)−1, p = 1.51 × 10−6). The same was seen for the 30 min insulin response (p = 4.17 × 10−7). The relationship remained after adding in the other four susceptibility loci (30 min insulin response and beta cell glucose sensitivity, p < 0.001 and p = 0.003, respectively).

Conclusions/interpretation

This study shows how individual type 2 diabetes-risk alleles combine in an additive manner to impact upon pancreatic beta cell function in non-diabetic individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent genome-wide association analyses have identified novel type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci. These single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been detected within or close to FTO, CDKN2A/B, IGF2BP2, SLC30A8, CDKAL1 and HHEX/IDE, along with confirming the involvement of TCF7L2, PPARG and KCNJ11 [1–6]. Many of the confirmed type 2 diabetes variants have since been shown in population cohorts to alter beta cell function [7–13]. These studies include the RISC (Relationship between Insulin Sensitivity and Cardiovascular Disease) study [14], where we previously showed that CDKAL1 (rs10946398) and HHEX/IDE (rs1111875) loci were associated with altered beta cell function as measured by the 30 min insulin response and pancreatic beta cell glucose sensitivity derived from an OGTT [10]. The aim of this study was to test the cumulative effects of variants shown individually to alter beta cell function.

Methods

We included the CDKAL1 (rs10946398) and the HHEX/IDE (rs1111875) susceptibility loci as we have shown previously that they significantly affect pancreatic beta cell function individually in the RISC cohort. We also included TCF7L2 (rs7903146), as it remains the strongest genetic predictor of type 2 diabetes, and has been reported to associate with decreased pancreatic beta cell function [8, 15]. We next included these loci and those of the other four genes reported to alter beta cell function, CDKN2A/B (rs10811661), IGF2BP2 (rs4402960), SLC30A8 (rs13266634) and KCNJ11 (rs5219), in our model to test the effects of all seven variants. To do this we used the RISC cohort that comprises non-diabetic men and women of European ancestry from 19 centres across 13 different countries [14]. Volunteers were recruited as part of a long-term study of insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular disease and those with diabetes, hypertension or dyslipidaemia were excluded. The analysis presented here is based on 1,211 individuals who had passed the eligibility criteria and had completed genotype data. We studied the same indices of pancreatic beta cell function. The 30 min insulin response is the ratio of the insulin concentration increment to the 30 min glucose concentration ([30 min insulin (pmol/l)–0 min insulin (pmol/l)]/[30 min glucose (mmol/l)]). Pancreatic beta cell glucose sensitivity is the slope of the dose–response curve between model-derived measures of insulin secretion vs plasma glucose concentration achieved during the OGTT [16]. Log10 transformation was used to normalise distributions and data are reported as geometric mean and SEM. Individuals were genotyped by KBioscience (http://www.kbioscience.co.uk/) at each of the type 2 diabetes-risk loci and then classified according to the total number of risk alleles that they carried. So for the initial three loci analysis, an individual homozygous for the risk allele at one locus, and heterozygous at the other two loci would carry a total of four risk alleles. Individuals with five or six risk alleles were grouped together in view of the relatively small number of individuals. For the analysis which looked at all seven loci, individuals were grouped together if they carried four or fewer, or nine or more. Statistical analyses were performed using Minitab version 15. Linear trend analysis (additive model) was performed to test for associations between the CDKAL1, HHEX/IDE and TCF7L2 SNP genotypes and 30 min insulin response, then beta cell glucose sensitivity after adjusting for age, sex and recruitment centre. Interaction analysis was performed using Stata. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

All SNPs were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Although all analyses were corrected for recruitment centre, we compared genotype frequencies between individuals from North and South European recruitment centres and found no significant differences.

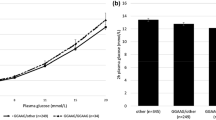

First, we confirmed that the TCF7L2 risk allele was individually associated with decreased early insulin response to an OGTT (p = 0.038) as previously reported [15]. Combining the diabetes-risk alleles for CDKAL1 (rs10946398), HHEX/IDE (rs1111875) and TCF7L2 (rs7903146) loci showed an additive model of association with measures of beta cell function. The additive effects of the three risk variants were associated with a decrease in 30 min insulin response (p = 4.17 × 10−7). This was decreased by 43% in the 3.1% of the cohort with five or more risk alleles compared with the 3.2% that carried no risk alleles (geometric mean [SEM]) (18.9 [1.09] vs 33.1 [1.12] pmol/mmol). The same was seen with beta cell glucose sensitivity (Fig. 1, p = 1.51 × 10−6). This was decreased by 39% in those individuals with five or more risk alleles compared with those individuals with no risk alleles (84 [1.07] vs 137 [1.11] pmol min−1 m−2 [mmol/l]−1). Interaction analyses showed that none of the comparisons was significantly different between a purely additive model and a full model containing interaction terms. From this we can determine that there is no evidence of deviation from additive effects within or between the susceptibility loci. Other key demographic and metabolic data for the individuals with combined risk alleles are summarised in Table 1.

Relationships between CDKAL1 (rs10946398), HHEX/IDE (rs1111875) and TCF7L2 (rs7903146) combined genotypes and 30 min insulin response (a), p = 4.17 × 10−7, and beta cell glucose sensitivity (b), p = 1.51 × 10−6. Blood was sampled at 30 min intervals during the OGTT to form the basis for modelling the estimates of glucose sensitivity. Data are presented as the geometric mean (SEM) after adjustment for age, sex and recruitment centre

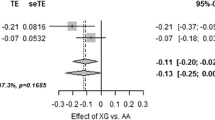

Although the other novel genes, CDKN2A/B, IGF2BP2, SLC30A8 and KCNJ11 have been shown to be associated with indices of pancreatic beta cell function in other studies [7, 11, 12], they did not reach statistical significance individually in our cohort [10]. However, when we included them in our additive model the relationships between increasing number of risk alleles and decreasing 30 min insulin response and decreasing beta cell glucose sensitivity still remained significant (p < 0.001 and p = 0.003, respectively). Between the 8% of the cohort with four or fewer risk alleles and the 16.8% with nine or more risk alleles there was a 21.8% decrease in 30 min insulin response and 29.6% decrease in pancreatic beta cell glucose sensitivity.

We have previously shown that common type 2 diabetes risk alleles combine in an additive manner to increase diabetes risk in individuals carrying multiple susceptibility alleles [17]. This is the first study to show that risk alleles individually associated with impaired pancreatic beta cell function combine in the same additive manner to markedly decrease beta cell function in individuals carrying multiple susceptibility alleles. The additive impact upon beta cell glucose sensitivity is of particular interest, as decreased beta cell glucose sensitivity in non-diabetic individuals has been shown to be a powerful, independent predictor for progression to type 2 diabetes [18]. Importantly, the decrease in the indices of beta cell function with increasing number of risk alleles was not a function of changes in whole-body insulin sensitivity (M/I), which essentially remained unchanged, as shown in Table 1.

Further testing in other population-based studies is required to validate our results. Larger studies have also confirmed susceptibility loci within the SLC30A8, CDKN2A/B, IGF2BP2 and KCNJ11 genes as altering beta cell function, so larger studies may refine our initial estimates [7, 11, 12].

In conclusion, while individual susceptibility alleles only moderately alter pancreatic beta cell function, the risk is additively increased when risk alleles are combined. Our study provides a validation of the additive model by which risk alleles combine to increase disease susceptibility.

Abbreviations

- RISC:

-

Relationship between Insulin Sensitivity and Cardiovascular Disease study

- SNP:

-

single-nucleotide polymorphism

References

Sladek R, Rocheleau G, Rung J et al (2007) A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature 445:881–885

Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN et al (2007) A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science 316:889–894

Diabetes Genetics Initiative of Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT Lund University and Novartis Institutes of BioMedical Research (2007) Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science 316:1331–1336

Zeggini E, Weedon MN, Lindgren CM et al (2007) Replication of genome-wide association signals in UK samples reveals risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Science 316:1336–1341

Scott LJ, Mohlke KL, Bonnycastle LL et al (2007) A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science 316:1341–1345

Steinthorsdottir V, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I et al (2007) A variant in CDKAL1 influences insulin response and risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 39:770–775

Nielsen E-MD, Hansen L, Carstensen B et al (2003) The E23K variant of Kir6.2 associates with impaired post-OGTT serum insulin response and increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 52:573–577

Loos RJF, Franks PW, Francis RW et al (2007) TCF7L2 polymorphisms modulate proinsulin levels and beta-cell function in a British Europid population. Diabetes 56:1943–1947

Staiger H, Machicao F, Stefan N et al (2007) Polymorphisms within novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes determine beta-cell function. PLoS ONE 2:e832

Pascoe L, Tura A, Patel S et al (2007) Common variants of the novel type 2 diabetes genes, CDKAL1 and HHEX/IDE, are associated with decreased pancreatic beta-cell function. Diabetes 56:3101–3104

Grarup N, Rose CS, Andersson EA et al (2007) Studies of association of variants near the HHEX, CDKN2A/B, and IGF2BP2 genes with type 2 diabetes and impaired insulin release in 10,705 Danish subjects: validation and extension of genome-wide association studies. Diabetes 56:3105–3111

Boesgaard T, Žilinskaitė J, Vänttinen M et al (2008) The common SLC30A8 Arg325Trp variant is associated with reduced first-phase insulin release in 846 non-diabetic offspring of type 2 diabetes patients—the EUGENE2 study. Diabetologia 51:816–820

Stancakova A, Pihlajamaki J, Kuusisto J et al (2008) Single nucleotide polymorphism rs7754840 of CDKAL1 is associated with impaired insulin secretion in non-diabetic offspring of type 2 diabetic subjects and in a large sample of men with normal glucose tolerance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:1924–1930

Hills S, Balkau B, Coppack S et al (2004) The EGIR-RISC STUDY (The European group for the study of insulin resistance: relationship between insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular disease risk): I. Methodology and objectives. Diabetologia 47:566–570

Lyssenko V, Lupi R, Marchetti P et al (2007) Mechanisms by which common variants in the TCF7L2 gene increase risk of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest 117:2155–2163

Mari A, Tura A, Gastaldelli A, Ferrannini E (2002) Assessing insulin secretion by modelling in multiple-meal tests: role of potentiation. Diabetes 51(Suppl 1):S221–S226

Weedon MN, McCarthy MI, Hitman G et al (2006) Combining information from common type 2 diabetes risk polymorphisms improves disease prediction. PLoS Medicine 3:e374

Walker M, Mari A, Jayapaul M, Bennett S, Ferrannini E (2006) Impaired beta-cell glucose sensitivity and whole-body insulin sensitivity as predictors of hyperglycaemia in non-diabetic subjects. Diabetologia 49:1456–1456

Acknowledgements

The RISC Study is supported by European Union grant QLG1-CT-2001–01252 and AstraZeneca. L. Pascoe is the recipient of a joint BBSRC and Unilever UK CASE PhD studentship.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 14.5 KB)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pascoe, L., Frayling, T.M., Weedon, M.N. et al. Beta cell glucose sensitivity is decreased by 39% in non-diabetic individuals carrying multiple diabetes-risk alleles compared with those with no risk alleles. Diabetologia 51, 1989–1992 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-008-1124-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-008-1124-7