Abstract

Background

Capsular serotypes K1 and K2 of Klebsiella pneumoniae are thought to the major virulence determinants responsible for liver abscess. The intestine is one of the major reservoirs of K. pneumoniae, and epidemiological studies have suggested that the majority of K. pneumoniae infections are preceded by colonization of the gastrointestinal tract. The possibility of fecal-oral transmission in liver abscess has been raised on the basis of molecular typing of isolates. Data on the serotype distribution of K. pneumoniae in stool samples from healthy individuals has not been previously reported. This study investigated the seroepidemiology of K. pneumoniae isolates from the intestinal tract of healthy Chinese in Asian countries. Stool specimens from healthy adult Chinese residents of Taiwan, Japan, Hong Kong, China, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam were collected from August 2004 to August 2010 for analysis.

Results

Serotypes K1/K2 accounted for 9.8% of all K. pneumoniae isolates from stools in all countries. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of K1/K2 isolates among the countries excluding Thailand and Vietnam. The antimicrobial susceptibility pattern was nearly the same in K. pneumoniae isolates. The result of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis revealed no major clonal cluster of serotype K1 isolates.

Conclusions

The result showed that Chinese ethnicity itself might be a major factor predisposing to intestinal colonization by serotype K1/K2 K. pneumoniae isolates. The prevalent serotype K1/K2 isolates may partially correspond to the prevalence of K. pneumoniae liver abscess in Asian countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Klebsiella pneumoniae is responsible for a wide spectrum of clinical syndromes, including purulent infections, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, bacteremia, septicemia, and meningitis [1]. In the past three decades, K. pneumoniae has emerged as the single leading cause of pyogenic liver abscess in East Asian countries, especially in Taiwan [2–7]. An invasive syndrome of liver abscess complicated by meningitis, endophthalmitis or other metastatic suppurative foci has been reported, and capsular serotypes K1 and K2 of K. pneumoniae are thought to the major virulence determinants responsible for this syndrome [3, 6, 8]. In an analysis of K. pneumoniae liver abscess from two hospitals in New York by Rahimian et al. [9], 78.3% of patients were of Asian origin. These findings raise the possibility that genetic susceptibility to or geographic distribution patterns of virulent K. pneumoniae subtypes may play important roles [10].

The intestine is one of the major reservoirs of K. pneumoniae, and epidemiological studies have suggested that the majority of K. pneumoniae infections are preceded by colonization of the gastrointestinal tract [11]. The possibility of fecal-oral transmission has been raised on the basis of molecular typing of isolates from siblings, family members, and the environment in one study from Taiwan [12]. One recent study from Japan has demonstrated the familial spread of a virulent clone of K. pneumoniae causing primary liver abscess, and has provided evidence that virulent clones of K. pneumoniae have colonized family members for at least 2 years [13]. However, data on the serotype distribution of K. pneumoniae in stool samples from healthy individuals has not been previously reported.

To explore the ethnicity and geographical question regarding the serotype distribution of K. pneumoniae from fecal isolates in different countries, we focused on the same population but in different countries. Therefore, this study investigated the seroepidemiology of K. pneumoniae colonizing the intestinal tract, using stool specimens from healthy Chinese adults in different Asian countries.

Results

Rate of K. pneumoniae isolation from stool specimens

During the study period, a total of 592 (62.1%) K. pneumoniae strains were isolated from 954 collected stool specimens. The isolation rate was highest in Malaysia (64/73, 87.7%), followed by Taiwan (150/200, 75%) and Singapore (47/77, 61.1%). The isolation rate was lowest in Japan (6/32, 18.8%) (Table 1).

Seroepidemiology

Antisera of the recognized 77 serotypes (designated K1-K74 and K80-K82) were used to analyze the isolates. Table 2 shows the distribution of serotypes among the 592 K. pneumoniae isolates from stool specimens of healthy Chinese and overseas Chinese adults in different Asian countries. Table 3 shows the distribution of serotypes K1/K2 isolates in different countries. Serotypes K1/K2 isolates accounted for 9.8% of all K. pneumoniae strains in all countries. Compared with other countries, Taiwan did not have a significantly higher prevalence of serotypes K1/K2 K. pneumoniae (11.3% vs. 9.3%, p = 0.46). When excluding Thailand and Vietnam, the prevalence of K1/K2 isolates did not differ among the countries (p = 0.98).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

We randomly and proportionally selected 100 serotypable isolates from different countries for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. The antimicrobial susceptibility pattern was the same in all 97 K. pneumoniae isolates, with uniform resistance to ampicillin and susceptibility to all cephalosporins and aminoglycosides. Serotypes K1/K2 and non-K1/K2 had the same antimicrobial susceptibility pattern (data not shown). Two isolates, including one serotype K1 isolate from Taiwan and one non-K1/K2 serotype from Thailand, were resistant to ampicillin and cefazolin but susceptible to other cephalosporins and aminoglycosides. One serotype K1 isolate from Taiwan was resistant to ampicillin, cefazolin, and amikaicin, but susceptible to other cephalosporins. No extended spectrum β-lactamase isolate was detected during this study.

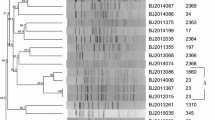

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and screening for CC23 representatives by detection of allS by PCR among K1 isolates

PFGE and detection of allS gene by PCR among serotype K1 isolates are shown in Figure 1. The original PFGE profiles are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. 31 (79.5%) of the K1 isolates carried allS gene. No major cluster was found among serotype K1 isolates from Asian countries, using previously described criteria [3].

Discussion

The K1 serotype of K. pneumoniae was uncommon among clinical isolates before the 1990s [14]. However, K1 serotype infection has been more widespread in Asian countries despite a recently reported increasing role of K. pneumoniae in liver abscess in the United States [15, 16]. The reason for the epidemiological changes and global differences observed remains unexplained. In this study focusing on Chinese in different Asian regions, a substantial proportion of serotype K1/K2 K. pneumoniae strains colonizing the intestine, except for Thailand and Vietnam, suggest that Chinese ethnicity itself might be a major factor predisposing to intestinal colonization by these strains. It also corresponds to the prevalence of liver abscess in Asian countries. The differences in socioeconomic factors, dietary practices, environmental exposure, living conditions, and the use of antimicrobial agents might also have a potential role for the geographic differences in seroepidemiology among K. pneumoniae isolates.

In our previous study in Taiwan, 77.6% of K. pneumoniae liver abscesses were caused by serotype K1 or K2 isolates [3]. A previous study has found that K. pneumoniae isolates from patients with liver abscesses in Singapore and Taiwan have similar characteristics, such as genomic heterogeneity and prevalence of virulence factors [6]. The prevalence of serotypes K1/K2 K. pneumoniae colonizing the intestinal tract in Taiwan is similar to that in Singapore. The prevalence of serotype K1/K2 K. pneumoniae isolates colonizing the intestine may contribute to invasive liver abscess syndrome in Taiwan and Singapore.

In Hong Kong, serotype K1 isolates from liver abscess specimens were studied, but the associated clinical details of the patients were not available [17]. A recent study from Japan has reported familial spread of a K1 clone of K. pneumoniae causing primary liver abscess [13]. In another study from Malaysia [18], K. pneumoniae rarely caused liver abscess and isolates were not serotyped [18]. In a recent study in China, K. pneumoniae was the prevalent pathogen in liver abscess but the serotypes of isolates were unavailable [19]. Further research focusing on serotype of K. pneumoniae isolates in these countries might clarify the relation between colonization and infection. K. pneumoniae-associated liver abscess caused by serotype K1 has never been reported in Thailand or Vietnam. Interestingly, we did not find any serotype K1 K. pneumoniae isolate from stools in the two countries.

In the present study, there was no major clonal cluster of serotype K1 isolates in Asian countries. Although one previous study of the molecular epidemiology of liver abscess in Taiwan identified a major cluster of K. pneumoniae isolates causing liver abscess [20], subsequent studies with the methods of ribotyping and PFGE have shown that K. pneumoniae-related liver abscesses are not caused by a clonally-spread strain [3, 21, 22]. Another study has further demonstrated that K. pneumoniae isolates causing liver abscess are not clonal in either Singapore or Taiwan [6]. Turton et al. firstly reported that the prevalence of strain ST23 in liver abscesses in Taiwan was high and that the strains were clonally related [17]. In the current study, we screened for strain CC23 representatives by detection of allS by PCR [23] and found that isolates carrying allS were also predominant in serotype K1 K. pneumoniae present in healthy adult stools. However, isolates carrying allS from stools were not related by PFGE, indicating that a geographic difference might account for the diversity.

An important limitation of this study was the lack of data regarding Chinese residents in Korea. Invasive liver abscess caused by K. pneumoniae K1 serotype has been emerging in Korea [5, 24]. A further study of the serotype and genetic relatedness of K. pneumoniae isolates colonizing the intestine in Korea may elucidate the epidemiology of emerging disease caused by K1 K. pneumoniae in Asia. Future investigation of K. pneumoniae from stools in Western countries is also needed to delineate the global epidemiology and the relation with K. pneumoniae liver abscess.

Conclusions

This is believed to be the first report to demonstrate the seroepidemiology of K. pneumoniae colonizing the intestinal tract of Chinese healthy adults in Asian countries. Serotype K1/K2 comprised 9.8% of the K. pneumoniae strains in this study. The antimicrobial susceptibility pattern was nearly the same in K. pneumoniae isolates, with uniform resistance to ampicillin and susceptibility to all cephalosporins and aminoglycosides. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of K1/K2 isolates among the countries, excluding Thailand and Vietnam. No major clonal cluster was found among serotype K1 isolates in Asian countries. Chinese ethnicity itself might be a major factor predisposing to intestinal colonization by these strains. The prevalent serotype K1/K2 isolates may partially correspond to the prevalence of K. pneumoniae liver abscess in Asian countries.

Methods

Sample collection and bacterial identification

In this study, stool specimens from healthy adult Chinese residents of Taiwan, Hong Kong and China, and overseas Chinese in Japan, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam were collected from August 2004 to August 2010. A total of 954 healthy adult volunteers (age > 20 years old) were invited to participate and provide stool samples for the study. They had no history of travel abroad, no gastrointestinal disease, and no hospital admission in the past year. None of them had been given any antibiotics during the 3 months before collection of the stool samples.

Stool samples were collected and placed in Cary-Blair transport medium, transported to a microbiology laboratory and inoculated on MacConkey agar plates and K. pneumoniae selective medium for the isolation of K. pneumoniae. The API 20E system (Bio-Merieux, Marcy I'Etoile, France) was used to identify isolates of K. pneumoniae. During the study period, the participants gave oral consent and voluntarily provided their stool samples for analysis of K. pneumoniae after stool routine procedures in the physical check-up. It was not possible to identify the patients from the data; therefore, the study was considered exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital.

Serotyping and PCR

All isolates were serotyped by a countercurrent immunoelectrophoresis method [25]. Antisera were kindly provided by the Laboratory of HealthCare Associated Infection, Centre for Infections, Health Protection Agency, London. K. pneumoniae ATCC9997 (K2) was used as a control strain. K1 and K2 isolates were confirmed by PCR as described previously [26]. All K1 isolates were screened for CC23 representatives by detection of allS by PCR as described previously [23].

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Susceptibility to antimicrobial agents was determined by the disc diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar medium (BBL Microbiological Systems, Cockeysville, MD, USA). The antibiotics tested were ampicillin (10 μg), cefazolin (30 μg), cefonicid (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), cefoperazone (75 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), and amikacin (30 μg). Interpretations were performed according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines [27].

PFGE

Total DNA was prepared, and PFGE was performed as described previously [3]. The restriction enzyme XbaI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA) was used. Restriction fragments were separated by PFGE in 1% agarose gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) in 0.5 × Tris-boric acid-EDTA buffer using a Bio-Rad CHEF-Mapper apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA, USA). Gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV light. Dendrograms showing percentage similarity were developed with Molecular Analyst Fingerprinting Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and compared using the UPGMA clustering method. A similarity coefficient > 80% was selected to define a major cluster.

Statistical analysis

Contingency data were analyzed by two-tailed χ2 test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. A p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant, and all probabilities were two-tailed. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Podschun R, Ullmann U: Klebsiellspp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998, 11: 589-603.

Wang JH, Liu YC, Lee SS, Yen MY, Chen YS, Wann SR, Lin HH: Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumonia in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis. 1998, 26: 1434-1438. 10.1086/516369.

Fung CP, Chang FY, Lee SC, Hu BS, Kuo BI, Liu CY, Ho M, Siu LK: A global emerging disease of Klebsiella pneumonia liver abscess: is serotype K1 an important factor for complicated endophthalmitis?. Gut. 2002, 50: 420-424. 10.1136/gut.50.3.420.

Ko WC, Paterson DL, Sagnimeni AJ, Hansen DS, Von Gottberg A, Mohapatra S, Casellas JM, Goossens H, Mulazimoglu L, Trenholme G, et al: Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumonia bacteremia: global differences in clinical patterns. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002, 8: 160-166. 10.3201/eid0802.010025.

Chung DR, Lee SS, Lee HR, Kim HB, Choi HJ, Eom JS, Kim JS, Choi YH, Lee JS, Chung MH, et al: Emerging invasive liver abscess caused by K1 serotype Klebsiella pneumonia in Korea. J Infect. 2007, 54: 578-583. 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.11.008.

Yeh KM, Kurup A, Siu LK, Koh YL, Fung CP, Lin JC, Chen TL, Chang FY, Koh TH: Capsular serotype K1 or K2, rather than magA and rmpA, is a major virulence determinant for Klebsiella pneumonia liver abscess in Singapore and Taiwan. J Clin Microbiol. 2007, 45: 466-471. 10.1128/JCM.01150-06.

Lok KH, Li KF, Li KK, Szeto ML: Pyogenic liver abscess: clinical profile, microbiological characteristics, and management in a Hong Kong hospital. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2008, 41: 483-490.

Fang CT, Lai SY, Yi WC, Hsueh PR, Liu KL, Chang SC: Klebsiella pneumonia genotype K1: an emerging pathogen that causes septic ocular or central nervous system complications from pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 2007, 45: 284-293. 10.1086/519262.

Rahimian J, Wilson T, Oram V, Holzman Robert S: Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2004, 39: 1654-1659. 10.1086/425616.

Nadasy KA, Domiati-Saad R, Tribble MA: Invasive Klebsiella pneumonia syndrome in North America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007, 45: e25-28. 10.1086/519424.

Montgomerie JZ: Epidemiology of Klebsiell and hospital-associated infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1979, 1: 736-753. 10.1093/clinids/1.5.736.

Chiu CH, Su LH, Wu TL, Hung IJ: Liver Abscess Caused by Klebsiella pneumonia in Siblings. J Clin Microbiol. 2001, 39: 2351-2353. 10.1128/JCM.39.6.2351-2353.2001.

Harada S, Tateda K, Mitsui H, Hattori Y, Okubo M, Kimura S, Sekigawa K, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto N, Itoyama S, et al: Familial spread of a virulent clone of Klebsiella pneumonia causing primary liver abscess. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49: 2354-2536. 10.1128/JCM.00034-11.

Cryz SJ, Mortimer PM, Mansfield V, Germanier R: Seroepidemiology of Klebsiella bacteremi isolates and implications for vaccine development. J Clin Microbiol. 1986, 23: 687-690.

Fang FC, Sandler N, Libby SJ: Liver abscess caused by magA + Klebsiella pneumonia in North America. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43: 991-992. 10.1128/JCM.43.2.991-992.2005.

Lederman ER, Crum NF: Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumonia as a primary pathogen: an emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005, 100: 322-331. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40310.x.

Turton JF, Englender H, Gabriel SN, Turton SE, Kaufmann ME, Pitt TL: Genetically similar isolates of Klebsiella pneumonia serotype K1 causing liver abscesses in three continents. J Med Microbiol. 2007, 56: 593-597. 10.1099/jmm.0.46964-0.

Goh KL, Wong NW, Paramsothy M, Nojeg M, Somasundaram K: Liver abscess in the tropics: experience in the University Hospital, Kuala Lumpur. Postgrad Med J. 1987, 63: 551-554. 10.1136/pgmj.63.741.551.

Li J, Fu Y, Wang JY, Tu CT, Shen XZ, Li L, Jiang W: Early diagnosis and therapeutic choice of Klebsiella pneumonia liver abscess. Front Med China. 2010, 4: 308-316. 10.1007/s11684-010-0103-9.

Lau YJ, Hu BS, Wu WL, Lin YH, Chang HY, Shi ZY: Identification of a major cluster of Klebsiella pneumonia isolates from patients with liver abscess in Taiwan. J Clin Microbiol. 2000, 38: 412-414.

Chang SC, Fang CT, Hsueh PR, Chen YC, Luh KT: Klebsiella pneumonia isolates causing liver abscess in Taiwan. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000, 37: 279-284. 10.1016/S0732-8893(00)00157-7.

Lee CH, Leu HS, Wu TS, Su LH, Liu JW: Risk factors for spontaneous rupture of liver abscess caused by Klebsiella pneumonia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005, 52: 79-84. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.12.016.

Brisse S, Fevre C, Passet V, Issenhuth-Jeanjean S, Tournebize R, Diancourt L, Grimont P: Virulent clones of Klebsiella pneumonia: identification and evolutionary scenario based on genomic and phenotypic characterization. PLoS One. 2009, 4: e4982-10.1371/journal.pone.0004982.

Kim JK, Chung DR, Wie SH, Yoo JH, Park SW: Risk factor analysis of invasive liver abscess caused by the K1 serotype Klebsiella pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009, 28: 109-111. 10.1007/s10096-008-0595-2.

Palfreyman JM: Klebsiell serotyping by counter-current immunoelectrophoresis. J Hyg (Lond). 1978, 81: 219-225. 10.1017/S0022172400025043.

Turton JF, Baklan H, Siu LK, Kaufmann ME, Pitt TL: Evaluation of a multiplex PCR for detection of serotypes K1, K2 and K5 in Klebsiell sp. and comparison of isolates within these serotypes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008, 284: 247-52. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01208.x.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI): Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 20th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S20. 2010

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from National Science Council (NSC92-2314-B-075-043 and NSC93-2314-B010-062), and Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V100C-083 and V100A-008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

YTL participated in the study design, carried out laboratory work, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. LKS participated in the study design, collected the specimens, carried out laboratory work, and analyzed the data. JCL participated in the study design, carried out laboratory work, and analyzed the data. TLC conceived the study, collected the specimens, and edited the manuscript. CPT, KMY and FYC conceived the study and edited the manuscript. CPF conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, collected the specimens, analyzed the data, edited the manuscript, and received the majority of funding needed to complete the research. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, YT., Siu, L.K., Lin, JC. et al. Seroepidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae colonizing the intestinal tract of healthy chinese and overseas chinese adults in Asian countries. BMC Microbiol 12, 13 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-12-13

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-12-13