Abstract

Background

DNA-based methods like PCR efficiently identify and quantify the taxon composition of complex biological materials, but are limited to detecting species targeted by the choice of the primer assay. We show here how untargeted deep sequencing of foodstuff total genomic DNA, followed by bioinformatic analysis of sequence reads, facilitates highly accurate identification of species from all kingdoms of life, at the same time enabling quantitative measurement of the main ingredients and detection of unanticipated food components.

Results

Sequence data simulation and real-case Illumina sequencing of DNA from reference sausages composed of mammalian (pig, cow, horse, sheep) and avian (chicken, turkey) species are able to quantify material correctly at the 1% discrimination level via a read counting approach. An additional metagenomic step facilitates identification of traces from animal, plant and microbial DNA including unexpected species, which is prospectively important for the detection of allergens and pathogens.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that deep sequencing of total genomic DNA from samples of heterogeneous taxon composition promises to be a valuable screening tool for reference species identification and quantification in biosurveillance applications like food testing, potentially alleviating some of the problems in taxon representation and quantification associated with targeted PCR-based approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Biosurveillance is a necessary task to monitor food for human consumption and pharmaceutical drugs, subsumed as “biologicals”, which typically consist of complex mixtures of processed biological material. Since the species origin of such products is often unclear, there is a concern about fraud, health risks and violation of ethical/religious principles, as best illustrated by the 2013 European horse meat case (for a further bizarre example see: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-17980177). Therefore, food and drug legislation demands producers to provide a proper declaration of ingredients, e.g. by naming species components of food products [1, 2]. To ensure correct declaration, accurate and efficient analytical methods of foodstuff analysis have been developed, mostly based on the detection of species on the DNA level by PCR [3, 4]. Such DNA-based tests are considered superior to protein-based methods, when processed material has to be analyzed [5]. Real-time PCR assays, often based on fast-evolving gene regions from the abundant mitochondrial genome, now facilitate a multiplex detection of many bird, fish and mammalian taxa [6–9]. Such assays sometimes even allow for discrimination of taxa as closely related as cow and water buffalo [10]. The main shortcoming of PCR-based detection methods is, however, that they inherently target only DNA from species to which the PCR primers bind efficiently. This caveat also holds true in principle for barcoding methods that rely on the PCR amplification and subsequent massively parallel next-generation sequencing of amplicons from variable genomic or cell organelle DNA regions (e.g. 16S rDNA, rDNA-ITS or mitochondrial COI [11]). Barcoding methods have been shown to very efficiently identify taxa within environmental or food-derived metagenomic samples in a qualitative way [12–15], but require separate assays to address the different domains of life. In addition, quantification of components by barcode sequencing has proven problematic due to taxonomic biases induced by the varying primer binding efficiencies across taxa ([13–16]; and references therein). Species quantification by sequencing of organellar PCR amplicons is also critical, as the absolute number of mitochondrial genomes per cell is highly fluctuating already between different tissues (e.g. eight-fold within different human cell types [17]). In contrast, sequence analysis of total genomic DNA isolated from food offers in principle the possibility to detect species in a totally unbiased way, enabling e.g. the detection of fraud through admixture of undeclared ‘exotic’ taxa or the presence of health risks by microbial contamination [4]. In the field of gene expression analysis, NGS sequencing facilitates a robust quantitative analysis of RNA molecules through digitally counting sequence reads obtained from the cDNA population of a tissue [18, 19]. The sensitivity and dynamic range of read counting equals or supersedes other quantitative DNA analytical methods like microarrays or SAGE [20, 21]. From a technical perspective, species identification based on the whole-genome sequencing should also be feasible since the large, non-protein-coding part of eucaryotic genomes evolves rather quickly and strongly conserved gene exons constitute only a minor proportion, e.g. roughly 1.5% of a mammalian genome [22]. Therefore, even closely related food-relevant taxa such as goat and sheep or turkey and chicken should be distinguishable in a total genomic comparison. Intraspecific polymorphism in foodstuff species ranges between 0.5 to 5 nucleotides per 1,000 bp in horse, swine and chicken, respectively [23–26], which should not substantially affect species discrimination.

Here we show that deep sequencing of total DNA derived from foodstuff material can readily identify and quantify species components with high accuracy by a single experimental assay. Sequence reads are assigned to species by mapping [27, 28] to publicly available reference genome sequences, which steadily grow in number, as exemplified by the Genome10k Project (https://genome10k.soe.ucsc.edu). At the same time, reads of “unexpected” species origin are readily detected by a metagenomic analysis based on DNA sequence database searching.

Methods

The bioinformatics pipeline

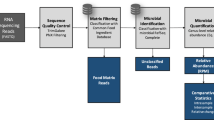

Sequence reads of 100 bp, either obtained by simulation (see below) or by Illumina sequencing of DNA from sausage meat (see below), were initially mapped against reference genomes using the algorithms BWA (V 0.7.0; [29]) or CUSHAW [30] resulting in a SAM file for each mapping. Reference genomes in our pilot analysis comprised the species Bos taurus, Bubalus bubalis, Equus caballus, Escherichia coli, Gallus gallus, Glycine max, Homo sapiens, Listeria seeligeri, Meleagris gallopavo, Mus musculus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Oryctolagus cuniculus, Oryza sativa, Ovis aries, Rattus norvegicus, Shigella boydii, Sus scrofa, Triticum aestivum and Zea mays (for details see Additional file 1). Reference genome taxa were mostly chosen either because of their foodstuff relevance or matches obtained in the metagenomic analyses step of our pipeline. Others (like human or rat) were primarily included to serve as negative controls to judge the extent of false positive read assignments. It is clear that for a broader screening many more reference genomes could have been used. The practical upper limit for the number of reference genomes clearly depends on computer power and scales linearly with time. The BWA mappings were executed by allowing 0, 1, 2 or 3 mismatches, depending on the respective approach (see below). For the downstream analysis of the mapping results we utilized SAMtools (V 0.1.18; [31]) and a set of self-implemented Perl scripts.After the mapping step, we identified three sets of sequence reads (Figure 1). The first set contained reads mapping to just one genome (“unique reads”). Assigning these reads to a genome and quantifying them by counting was a straightforward task. More challenging were reads, which covered conserved sequence regions within genomes and therefore simultaneously hit at least two different genomes (“multi-mapped reads”), even under conditions of the highest mapping stringency. Since these conserved reads cannot be assigned with any certainty to one specific genome, we distributed them to the respective candidate genomes in the proportion previously calculated from the unique reads. By this means, the multi-mapped reads could additively be used to improve the values of the quantitative analysis.

A 3rd category, so-called “unmapped reads”, were collected and forwarded to up to three further rounds of mapping, each of which allows one more mismatch than the previous round (i.e. in round 4 we had a matching stringency of 97%). We then calculated the proportions of species material from all reads, which were unambiguously assigned at this step. To account for the different quality (i.e. completeness) of the reference genomes, as indicated by different numbers of positions denoted by Ns in the genome drafts, our initial quantitative estimates were corrected by a genome quality factor f = (n + c)/c, where n is the number of ambiguous nucleotides and c is the total number of nucleotides in the reference genome. Further normalization should in principle be necessary to adjust for largely different genome sizes, e.g. when comparing birds and mammals which differ roughly 3-fold in DNA content [32, 33]. However, our quantification of a sample containing avian material (Additional file 2) indicated that such normalization might be unnecessary, possibly due to the correlation of smaller genome size with a smaller nucleus and cell size [34] leading to a compensatory denser packaging of cells per gram avian tissue.

In our pipeline, we subsequently tried to identify the origin of still unmapped reads by BLASTN (V 2.2.25) database searching [35] against the NCBI nucleotide database (nr/nt). Since our query sequences were short 100 bp reads, we used a word size of 11, set the BLAST e-value to 100 according to MEGAN’s “how to use BLAST” tutorial [36], and accepted the best three hits for further analysis. Furthermore, we set BLAST’s “–I” option to add the gi number to the default BLAST output files. Otherwise, default BLASTN settings were used. BLASTN results were then visualized by the metagenomic analysis tool MEGAN4 (V 4.70.4). This tool parses BLAST output files and assigns the results to species or, if this is not possible, taxonomic groups of higher rank according to the NCBI taxonomy database. To filter out false-positives, caused by low complexity repeats (e.g. microsatellites) or highly conserved regions, we set MEGAN’s LCA parameters to Min complexity = 0.44, Min Score = 75.0, Top percent = 1.0 and turned on the percent identity filter. To limit the analysis to the most relevant results, taxa were somewhat arbitrarily only accepted for visualization in our pilot study, if more than 50 reads were assigned to this taxon. BLAST results were then visualized as a phylogenetic tree and quantified using Excel. For species attracting more than a threshold number of the unmapped reads in the BLAST step, a return to the read mapping procedure would be reasonable to infer more exactly the proportion of this taxon. This, of course, requires the availability of the respective reference genome, the list of which is gradually increasing.

Dataset simulation and calculation

As a proof of principle, we simulated records of Illumina sequence data by randomly extracting 100 bp long sequences from downloaded genome sequences, which were subsequently tagged by their origin (Additional file 1). Random errors were introduced into the simulated reads at a 1% rate. Next, we compiled mixed datasets for testing the read-mapping pipeline, by randomly sampling subsets of these simulated sequence reads. For simplicity at this testing stage, we did not perform iterative mapping at different stringencies, but allowed only one mismatch in the mapping process. We also did not apply the genome quality factor.

Illumina sequencing of DNA from a sausage calibration sample

Total genomic DNA was extracted from 200 mg of the homogenized calibration sausages “KalD” (type “boiled sausage”) [37] and “KLyoA” (type “Lyoner”) [9] by the Wizard Plus Miniprep DNA purification system (Promega, Madison, USA). DNA was eluted in 50 μl elution buffer according to the supplier's manual. Illumina sequencing library preparation was conducted on 1.5 μg of total DNA by StarSEQ (Mainz, Germany) using the TruSeq DNA Sample Preparation Kit v.2 (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument (100 bp paired-end reads) for KalD and on a MiSeq instrument (50 bp single reads) for KLyoA. We used the FASTX toolkit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/index.html) for adapter clipping and quality filtering. Reads shorter than 50 bp (KalD) or 20 bp (KLyoA) were discarded.

Hardware for bioinformatical analyses

For the sake of speed, mappings using BWA were preferentially performed on one node (containing 4 CPUs with 16 cores each running at 2.1 GHz) of the Mogon Linux-Cluster at University of Mainz. Each iterative mapping (4 rounds, 0 to 3 mismatches) with 1 mio paired-end reads took about 45 minutes. Mapping on a standard PC (4 × 2.67 GHz, 16 GB RAM) consumed 3 hrs of time using 12 reference genomes (30 Gbp size) and 100,000 reads. The BLAST steps of the pipeline were run on the University of Mainz Central Computing Linux-Cluster Lc2 (Suse Linux Enterprise Server 10 SP2, 132 nodes containing 2 CPUs with 8 cores each running at 2.7 GHz). Blast requests (single-threaded) were split up to 1000 separate jobs, which reduced runtime to less than 2 hours for 200,000 queries. The MEGAN program was subsequently run on a standard personal computer (PC) with 8 GB RAM and Windows OS.

Results and discussion

Read mapping facilitates exact quantification of DNA from diverse species

To test if high-throughput genomic DNA sequencing was able to accurately determine the proportions of foodstuff components, we initially simulated two sets of sequencing records (Table 1 and 2). The simulated sequence data was based on randomly sampled sub-sequences of public available genomes with randomly introduced errors.

Dataset 1 consists of one million reads derived from six mammalian species (Table 1). After running our pipeline on this dataset, the proportions of reads assigned to the respective reference genomes mirrored the sample compounds with high accuracy. The artificial dataset contained sequences present in rather high quantities (60% for sheep) and low amounts (1% for human and rat) indicating that the method worked over a broad range of proportions. We achieved absolute differences between assigned reads and input read numbers of 0 to 0.19% (Table 1). The maximum relative difference (% absolute difference/% input DNA) was 1.67%. We also checked the accuracy of the mapping process by tracing the identity of the uniquely mapped reads (represented by different file paths). The mapping accuracy turned out to be better than 99.9% (cattle).

Simulation dataset 2 comprises 850 K reads, mixed at uneven proportions from three mammalian species (cattle, pig, sheep) and the bacterium E. coli (Table 2). This dataset was created to check if the method was able to detect signals of “unexpected” species, which would possibly not have a reference genome included in the initial mapping step. The sample was therefore initially run through the pipeline without mapping against bacterial genomes. As a result, all E. coli reads were passed on to the metagenomic BLAST/MEGAN step. By this database searching routine, 34,944 of 131,683 unmapped reads (=26.54%) were identified as possible E. coli signals. According to our pipeline rationale, the strong E. coli signal prompted us to add the E. coli genome to the mapping process and to run the pipeline again to achieve a better quantitative estimate of the bacterial reads. In fact, the proportion of E. coli reads was now determined at high accuracy with only 0.02% deviation from the real input value (Table 2). Meanwhile, the correct assignment of the E. coli reads improved the overall quantitative estimates for all the other species components.

These (and others, not reported) results of our simulation study proved the general feasibility of quantitative species identification through deep sequence analysis of total genomic DNA. Quantification was most exact for the read mapping process implemented in AFS, which however requires the availability of a reference genome. Given that vertebrate (and many other) species will soon be sequenced by the thousands, this requirement will not set a limiting condition on the method itself.

For identifying unexpected species, the application of a less stringent metagenomic search tool, based on a BLAST database search followed by visualization via MEGAN, also proved successful. However, our results for dataset 2 suggested that the mere evaluation of BLAST/MEGAN results would not facilitate an accurate quantitative measurement of read numbers, which is only possible via the more stringently working read mapping algorithms. It should also be stressed that the results of the metagenomic working step entirely depend on the completeness of the sequence database chosen for searching and on the representation of a particular species within a database partition. In addition, one should be cautious of erroneous annotations within public databases [38].

However promising the results of the simulation data analysis appeared, they clearly represented an idealized situation, since we obviously obtained the simulated reads from the very same genomes to which they were mapped thereafter. Hence, we conducted an analysis using real data.

Illumina sequencing of a DNA sample from calibration sausage material

Illumina sequencing was performed on DNA obtained from sausage material, which previously had been designed and produced as calibration sample for qPCR-based approaches to species identification (KalD, [37], KLyoA [9]). The sample KalD, on which we focused our most detailed analysis, contained material from four mammalian species (35% cattle, 1% horse, 9% pig, 55% sheep). These mammalian taxa feature a minimal interspecific nucleotide divergence at the level of synonymous sites within genes of 7% (for sheep-cattle; [39]), which is most probably exceeded by neutral non-genic sites. In addition, the sausage sample contained admixtures of 11 different plant allergens at varying amounts (R. Köppel, unpublished data; Additional file 3).

After quality filtering, we obtained 2 × 16 million 100 bp paired-end reads. Encouraged by the previous simulations, subsets of only 2 × 500 K (=1 mio) randomly selected paired-end reads were used for further analysis. To account for a possible trade-off between the specificity of taxon identification and a maximally exact quantification of reads, we devised two different mapping strategies. When maximum specificity was the prime goal (“AFS-spec”), we did not allow any mismatches during read mapping, and thus performed only a single mapping step with the highest stringency. In addition, we disabled the Smith-Waterman alignment option in BWA because it lowers the mapping stringency for a paired-end read when rescuing a read from its aligned mate. The second strategy (“AFS-quant”) aimed at best quantitative results. To this end, we performed an iterative read-mapping starting with a stringency of 0 and ending with 3 mismatches.

For both strategies, the n = 3 repetitions produced highly similar results, as evidenced by low standard deviations (Table 3). The AFS-quant approach delivered a highly accurate quantification of meat components in sausage KalD, as exemplified by the value of 54.8% DNA versus 55% (w/w) meat for sheep (Table 3). Absolute differences between the DNA proportions and the meat proportions ranged from 0.24 to 1.79%, showing that species quantification can be achieved at the 1% discrimination level. The highest divergence (1.79%) was observed for pig and can be explained by the use of lard tissue [40], which presumably contains less cells and thus DNA than e.g. muscle tissue. In this respect, AFS behaves in the same well-known matrix-dependent way as other DNA-based detection methods [40], and the definition of normalization values for typical ingredients and production recipes should alleviate this problem also for AFS.

To infer the specificity of the mapping procedure we included the reference genome sequence of water buffalo, which belongs to the same subfamily (Bovinae) as cattle. AFS-quant detected a false-positive proportion of 0.64% DNA reads in the buffalo genome (Table 3), which probably represent sequences strongly conserved between the two bovines. The more stringent AFS-spec approach was able to reduce the false-positive rate of “buffalo reads” substantially to 0.07%, but only at the expense of a markedly diminished accuracy for quantification of the real meat components (Table 3). To demonstrate the broader applicability of the AFS-quant approach we sequenced and quantified the main ingredients of the KLyoA sausage sample, which contains 0.5% chicken and 5.5% turkey on a background of pig and cattle meat (Additional file 2). The avian components were determined as accurate as the mammalian ones.

We conclude that the AFS-quant strategy delivers the most accurate quantitative species determination. We note that the AFS quantification results are equal to or sometimes even better than species analyses performed by quantitative PCR on the same sausage material [37]. AFS still contains a very low risk of obtaining false-positive matches to closely related species. Clearly, further case studies with other species pairs like horse-donkey, which diverged only 2.4 million years ago [41], have to be conducted to generalize our conclusions. As a screening procedure, AFS performance is only limited by the number of reference genomes available. Offering both, a qualitative and quantitative result, deep sequencing of total genomic DNA appears as an excellent alternative to microarray-based screening methods for species identification [42] or sequencing of PCR-based barcode amplicons [12, 13, 15].

Detection of “unexpected” species via metagenomic analysis

DNA reads which do not map to the selection of reference genomes will be passed over to the BLAST/MEGAN annotation procedure in AFS. The one-million-read datasets obtained from the KalD sausage each produced more than 200 K of unmapped reads (Figure 2). Roughly half of these reads could successfully be assigned to a species or higher ranked taxon. The other half was represented by two classes: (i) low-complexity repetitive DNA (e.g. microsatellites) which is present in almost all genomes and thus cannot be assigned unequivocally; and (ii) un-assignable reads which either did not match an entry in the chosen database or did not meet the stringent MEGAN criteria applied. Clearly, the choice of different specialized databases and perhaps less stringent match criteria has the potential of reducing this portion.

Metagenomic analysis of unmapped reads. Results of the metagenomic analysis of sequence reads obtained from the KalD reference sausage. The global result of the BLAST/MEGAN step is shown in the box (grey frame). A more detailed classification of matches is displayed for mammals, viruses, bacteria and plants.

The ca. 100 K reads that were taxonomically assigned by BLAST/MEGAN originated in their vast majority (98%) from mammals (Figure 2). Of those mammalian hits, 96% were annotated as cattle, sheep, pig and horse (i.e. those taxa which formed the sausage). Close inspection of these sequences revealed that they predominantly represented centromeric satellite DNA. This sequence class is usually not represented in genome reference sequences, explaining that the corresponding reads could not be assigned in the mapping step. The observed species proportions of the satellite DNA reads somewhat surprisingly did not match the meat proportions for cattle and sheep. A reason could be that centromeric DNA, which is an inherently unstable component of eucaryotic genomes [43], is present in different amounts in the heterochromatin of sheep and cattle chromosomes, making its use for quantification purposes problematic.

Among the reads of mammalian origins, we further recorded hits to several bovine-related taxa like the muntjac, goat or whales (Figure 2), which separated from bovines 25, 30 and 56 million years ago, respectively (http://www.timetree.org). We could show by an analysis using the tool REPEATMASKER (http://www.repeatmasker.org/) that these reads most often belonged to transposable elements (MIRs, LINEs, ERVs, DNA transposons) which show sequence conservation across this clade. Surprisingly, we also found ~500 matches to human, cercopithecan primates and mouse. Inspection of these BLAST hits revealed that they also contained interspersed repeats. However, in humans and monkeys, none of those reads corresponded to the primate-specific Alu element family. We are thus rather sure that neither goat or whale nor traces of human, monkey or mouse DNA are present in the sample. At the same time, this issue demonstrates that expert interpretation of BLAST results is required, which is by no means a simple task.

Beyond Mammalia, BLAST/MEGAN suggested the presence of viral, bacterial and plant sequences in the sausage DNA (Figure 2). Viral DNA, all belonging to bacteriophage PhiX174, was easily explained since this DNA is usually applied for technical reasons as a calibrator in Illumina sequencing (http://res.illumina.com/documents/products/technotes/technote_phixcontrolv3.pdf). Several hundred bacterial reads were detected, mostly originating from the human-pathogenic species Neisseria gonorrhoeae (n = 572 reads) or from Pseudomonadales (n = 64 reads), with Pseudomonas fluorescens as an often annotated species (n = 45 reads). The latter is notably present e.g. in deteriorating milk and meat products [44]. While the small numbers of P. fluorescens reads can be taken as an indicator of beginning food spoilage, the finding of Neisseria reads tells a very important cautionary tale in metagenomic analysis. After adding the respective genome [45] to the mapping process, presumed N. gonorrhoaea DNA was detected at an amount of 0.04%. Knowing that there should not be any N. gonorrhoeae material in the sample, we investigated this result further. By mapping all 32 million reads of our initial dataset to the N. gonorrhoeae genome, we obtained matches exclusively located in ten genomic regions, each shorter than 700 bp, where read coverage was extremely high (up to 5200-fold). These regions were extracted from the N. gonorrhoeae genome and analyzed by BLAST against the NCBI nucleotide database, thereby revealing strong homology of these parts to ruminant sequence entries (data not shown). In addition, mapping the sausage reads to other available N. gonorrhoeae genomes sequences did not produce any matches. We thus question the quality of the N. gonorrhoeae strain TCDC-NG08107 genome and recommend using it with high caution. In general, this points out that the annotation quality of database entries is of prime importance to species diagnosis.

Since meat products often contain plant material, the metagenomic analysis on the plant spectrum is of special interest. In fact, the sausage contained admixtures of 11 plant species (Additional file 3) to enable its use in the development of allergen detection methods. The most prominent spiked-in ingredients were lupine (Lupinus spec.), walnut (Juglans regia), hazelnut (Corylus avellana) and mustard (Brassica spec.). We detected 661 plant hits, which were assigned to a total of 33 plant families. Amongst those families, Brassicaceae (mustard) dominated with 449 hits, followed by Fabaceae (lupine, peanut, soy) with 62 hits (Figure 2; Additional file 3). All other plant ingredients received only from 1 to 17 BLAST hits. These numbers of database matches did not correlate with the amount of spiked-in plant material, illustrating that the current BLAST/MEGAN routine is by no means quantitative. A probable reason is the unbalanced representation of sequence entries for the different taxa in the database (data not shown). This can be overcome in future by the production of reference genomes for all major food- and allergenicity-relevant species. In addition, as expected for a DNA-based method, the quantification result will heavily depend on the efficiency of DNA recovery from the food matrix. Of all plant allergens tested, only the genome of soy (Glycine max) is publicly available and was thus included in the AFS read mapping step. We detected a stable proportion of 0.005% soy DNA in the sample, while the proportion of spiked-in soy material in the sausage was 0.0316%, suggesting a matrix-dependent underestimation by a factor of 6. We point out, however, that qualitative detection may be the prime goal in allergen analysis [46]. The limits of AFS for allergen detection clearly have to be investigated further.

Technical considerations and further improvements

Next-generation sequencing methods represent the fastest growing technology worldwide, with ever decreasing cost per analysis (http://www.genome.gov/sequencingcosts/). Applying novel 96-well format multiplex methods for Illumina library preparation (NEXTERA®) and a personal sequencer (MiSeq®) we calculate current sequencing cost (chemistry plus personnel, but excluding the bioinformatic analysis) at roughly 150–200 Euro per sample, which may already now be interesting and feasible for routine screening purposes. Although we produced 100 bp paired-end reads for the KalD sample, the initial results on KLyoA suggest that cost-saving 50 bp single-end reads will probably perform equally well in read mapping. However, shorter reads may pose more problems in database searches, unless the BLAST version is optimized for short query sequences.An additional cost saving can possibly be achieved by optimizing the numbers of sequence reads necessary to obtain stable quantification results. To this end, we mapped different numbers of reads, starting with 50 K and multiples thereof up to 10 mio reads, and calculated the sum of deviations (in%) of the observed from the expected species proportions (Figure 3). Deviations decreased with increasing dataset size, but were already close to the optimum at 1 mio reads. Even at 50 or 100 K reads, the sum of deviations was rather moderate, opening the perspective that even very small datasets will still guarantee a reasonable quantification result for the main sample ingredients.

Determination of the optimal number of sequence reads necessary to obtain accurate quantification results for species components. The number of sequence reads used in the mapping (x-axis) was plotted against the values of mapping accuracy (y-axis), calculated as the cumulated absolute deviation in% of mapping results versus expected species proportions.

Throughput of samples in time will improve, especially when using the MiSeq® instrument, running only 6 hrs for 50 bp reads. DNA size requirements (>300 bp) and input amounts needed (1 ng) for the NEXTERA XT® protocol [47] are routinely obtained in current PCR-based foodstuff analytics (reviewed in [48]). The slight chance for a wrong allocation of multiplexed samples, which may e.g. be due to erroneous bioinformatic sorting of multiplexing tags, will be substantially reduced by the use of two such tags per sample in the NEXTERA protocol [49, 50]. Another practical problem which has to be adequately addressed is the possible run-to-run carry-over of DNA molecules e.g. due to incomplete removal of residual DNA washing from the sequencing device. Illumina’s technical notes say that this detrimental effect is typically below 0.05% (thus affecting 500 reads in 1 million) and must be controlled by dedicated device maintenance procedures.

On the bioinformatic side, the read-mapping process can already be carried out on standard PCs with 4 GB of RAM using commercial software tools, but is still time-consuming when many reference genomes are inspected. New developments in software programming offer the use of fast and affordable graphics processing units (GPUs) to analyze massive sequence data in reasonable time. To test if such compute unified device architecture (CUDA)-based programs will speed up our pipeline, we compared the novel mapping tool CUSHAW [30] to the standard tool BWA for the time needed for analyze the species proportions of the sausage sample. While the accuracy using CUSHAW appeared somewhat lower than BWA possibly due to algorithmic differences (data not reported), time improvement using CUSHAW was substantial with a 2.0 to 2.6-fold speed-up, depending on the number of threads (one to eight) BWA was allowed to use. CUSHAW thus could cut the time needed for read mapping on a PC roughly by half.

The biggest limitation in our pipeline in terms of time and costs was set by the massive BLAST routines (carried out on our University high-performance cluster) necessary for the metagenomic step. Our adhoc calculations suggest that additional costs (ca. 100 EUR) have to be considered, if access to a commercial computing facility is needed. The cautionary tale of the wrongly assembled/annotated Neisseria reference genome in our metagenomic step illustrates that the correct interpretation of the BLAST/MEGAN results still requires substantial biological and bioinformatical knowledge. The use of curated sequence database information and/or the application of dedicated repositories containing validated species-specific sequence data (such as bar-coding targets; http://www.barcodeoflife.org/) will greatly simplify this step for non-specialists on the food control side. We wish to point out that a number of highly innovative approaches for the identification (but not necessarily quantification) of species have recently been established in the field of bacterial metagenomics, making use of curated taxon-specific sequence databases (e.g. MetaPhlAn [51]), ultrafast algorithms for sequence pattern recognition (e.g. k-mer based methods; [52]) or a probabilistic framework for read assignment to very closely related genomes (e.g. Pathoscope [53]). Integration of these tools is a promising option for further improvement of AFS.

Conclusion

AFS has the potential to be a valuable method for routine testing of food material and other biosurveillance applications, offering an attractive combination of unbiased screening for all types of ingredients and the possibility of simultaneously obtaining quantifiable results. Since deep DNA sequencing has already revolutionized biological and medical research, it may find its way into routine diagnostics soon. AFS implementation currently requires elaborate knowledge of genomes and bioinformatics, but several strategies are conceivable to further simplify and standardize the approach.

Abbreviations

- AFS:

-

All food sequencing

- KalD:

-

Kalibrator D

- KLyoA:

-

Kalibrator Lyoner A

- GPUs:

-

Graphics processing units

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing.

References

Das Eidgenössische Departement des Innern: Verordnung über Lebensmittel tierischer Herkunft. Swiss Food Legislation. 2005, 23: 11-Art. 8 Abs. 5

Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz: Gesetz über den Verkehr von Arzneimitteln. German Drug Law. 2011, 22: 12-Art. 10 & 11

Meyer R, Candrian U, Lüthy J: Detection of pork in heated meat products by the polymerase chain reaction. J AOAC Int. 1994, 77 (3): 617-622.

Woolfe M, Primrose S: Food forensics: using DNA technology to combat misdescription and fraud. Trends Biotechnol. 2004, 22 (5): 222-226.

Asensio L, Gonzalez I, Garcia T, Martin R: Determination of food authenticity by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Food Control. 2008, 19 (1): 1-8.

Brodmann PD, Moor D: Sensitive and semi-quantitative TaqMan™ real-time polymerase chain reaction systems for the detection of beef (Bos taurus) and the detection of the family Mammalia in food and feed. Meat Sci. 2003, 65 (1): 599-607.

Zhang CL, Scott NW, Lawson G, Slater A, Fowler: A TaqMan real-time PCR system for the identification and quantification of bovine DNA in meats, milks and cheeses. Food Control. 2007, 18 (9): 1149-1158.

Köppel R, Ruf J, Zimmerli F, Breitenmoser A: Multiplex real-time PCR for the detection and quantification of DNA from beef, pork, chicken and turkey. Eur Food Res Technol. 2008, 227 (4): 1199-1203.

Eugster A, Ruf J, Rentsch J, Koppel R: Quantification of beef, pork, chicken and turkey proportions in sausages: use of matrix-adapted standards and comparison of single versus multiplex PCR in an interlaboratory trial. Eur Food Res Technol. 2009, 230 (1): 55-61.

Sawyer J, Wood C, Shanahan D, Gout S, McDowell D: Real-time PCR for quantitative meat species testing. Food Control. 2003, 14 (8): 579-583.

Hebert PDN, Ratnasingham S, deWaard JR: Barcoding animal life: cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 divergences among closely related species. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 2003, 270: 96-99.

Coghlan ML, Haile J, Houston J, Murray DC, White NE, Moolhuijzen P, Bellgard MI, Bunce M: Deep Sequencing of Plant and Animal DNA Contained within Traditional Chinese Medicines Reveals Legality Issues and Health Safety Concerns. Plos Genet. 2012, 8 (4): 436-446.

Tillmar AO, Dell'Amico B, Welander J, Holmlund G: A Universal Method for Species Identification of Mammals Utilizing Next Generation Sequencing for the Analysis of DNA Mixtures. PLoS One. 2013, 8 (12): e83761-

Zhou X, Li Y, Liu S, Yang Q, Su X, Zhou L, Tang M, Fu R, Li J, Huang Q: Ultra-deep sequencing enables high-fidelity recovery of biodiversity for bulk arthropod samples without PCR amplification. GigaScience. 2013, 2 (1): 4-

Newmaster SG, Grguric M, Shanmughanandhan D, Ramalingam S, Ragupathy S: DNA barcoding detects contamination and substitution in North American herbal products. BMC Med. 2013, 11: 222-

Deagle BE, Thomas AC, Shaffer AK, Trites AW, Jarman SN: Quantifying sequence proportions in a DNA-based diet study using Ion Torrent amplicon sequencing: which counts count?. Mol Ecol Resour. 2013, 13 (4): 620-633.

Robin ED, Wong R: Mitochondrial-DNA Molecules and Virtual Number of Mitochondria Per Cell in Mammalian-Cells. J Cell Physiol. 1988, 136 (3): 507-513.

Marguerat S, Bahler J: RNA-seq: from technology to biology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010, 67 (4): 569-579.

Ozsolak F, Milos PM: RNA sequencing: advances, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Genet. 2011, 12 (2): 87-98.

Marioni JC, Mason CE, Mane SM, Stephens M, Gilad Y: RNA-seq: an assessment of technical reproducibility and comparison with gene expression arrays. Genome Res. 2008, 18 (9): 1509-1517.

Mortazavi A, Williams BA, Mccue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B: Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008, 5 (7): 621-628.

Dunham I, Kundaje A, Aldred SF, Collins PJ, Davis CA, Doyle F, Epstein CB, Frietze S, Harrow J, Kaul R, Khatun J, Lajoie BR, Landt SG, Lee BK, Pauli F, Rosenbloom KR, Sabo P, Safi A, Sanyal A, Shoresh N, Simon JM, Song L, Trinklein ND, Altshuler RC, Birney E, Brown JB, Cheng C, Djebali S, Dong X, Dunham I: An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012, 489 (7414): 57-74.

Wiedmann RT, Smith TPL, Nonneman DJ: SNP discovery in swine by reduced representation and high throughput pyrosequencing. BMC Genet. 2008, 9: 81-

Wade CM, Giulotto E, Sigurdsson S, Zoli M, Gnerre S, Imsland F, Lear TL, Adelson DL, Bailey E, Bellone RR, Blöcker H, Distl O, Edgar RC, Garber M, Leeb T, Mauceli E, MacLeod JN, Penedo MC, Raison JM, Sharpe T, Vogel J, Andersson L, Antczak DF, Biagi T, Binns MM, Chowdhary BP, Coleman SJ, Della Valle G, Fryc S, Guerin G: Genome sequence, comparative analysis, and population genetics of the domestic horse. Science. 2009, 326 (5954): 865-867.

Kerstens HHD, Crooijmans RPMA, Veenendaal A, Dibbits BW, Chin-A-Woeng TFC, den Dunnen JT, Groenen MAM: Large scale single nucleotide polymorphism discovery in unsequenced genomes using second generation high throughput sequencing technology: applied to turkey. BMC Genomics. 2009, 10: 479-

Kijas JW, Townley D, Dalrymple BP, Heaton MP, Maddox JF, McGrath A, Wilson P, Ingersoll RG, McCulloch R, McWilliam S, Tang D, McEwan J, Cockett N, Oddy VH, Nicholas FW, Raadsma H, International Sheep Genomics Consortium: A genome wide survey of SNP variation reveals the genetic structure of sheep breeds. PLoS One. 2009, 4 (3): e4668-

Pop M, Salzberg SL: Bioinformatics challenges of new sequencing technology. Trends Genet. 2008, 24 (3): 142-149.

Li H, Homer N: A survey of sequence alignment algorithms for next-generation sequencing. Brief in Bioinform. 2010, 11 (5): 473-483.

Li H, Durbin R: Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010, 26 (5): 589-595.

Liu Y, Schmidt B, Maskell DL: CUSHAW: a CUDA compatible short read aligner to large genomes based on the Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2012, 28 (14): 1830-1837.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R: The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009, 25 (16): 2078-2079.

Williams RBH, Cotsapas CJ, Cowley MJ, Chan E, Nott DJ, Little PFR: Normalization procedures and detection of linkage signal in genetical-genomics experiments. Nat Genet. 2006, 38 (8): 855-856.

Dalloul RA, Long JA, Zimin AV, Aslam L, Beal K, Le Blomberg A, Bouffard P, Burt DW, Crasta O, Crooijmans RPMA, Cooper K, Coulombe RA, De S, Delany ME, Dodgson JB, Dong JJ, Evans C, Frederickson KM, Flicek P, Florea L, Folkerts O, Groenen MA, Harkins TT, Herrero J, Hoffmann S, Megens HJ, Jiang A, de Jong P, Kaiser P, Kim H: Multi-platform next-generation sequencing of the domestic turkey (Meleagris gallopavo): genome assembly and analysis. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8 (9): e1000475-

Gregory TR: A bird's-eye view of the C-value enigma: Genome size, cell size, and metabolic rate in the class aves. Evolution. 2002, 56 (1): 121-130.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ: Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990, 215 (3): 403-410.

Huson DH, Mitra S, Ruscheweyh H-J, Weber N, Schuster SC: Integrative analysis of environmental sequences using MEGAN4. Genome Res. 2011, 21 (9): 1552-1560.

Köppel R, Ruf J, Rentsch J: Multiplex real-time PCR for the detection and quantification of DNA from beef, pork, horse and sheep. Eur Food Res Technol. 2011, 232 (1): 151-155.

Schnoes AM, Brown SD, Dodevski I, Babbitt PC: Annotation error in public databases: misannotation of molecular function in enzyme superfamilies. PLoS Comp Biol. 2009, 5 (12): e1000605-

Kijas JW, Menzies M, Ingham A: Sequence diversity and rates of molecular evolution between sheep and cattle genes. Anim Genet. 2006, 37 (2): 171-174.

Köppel R, Eugster A, Ruf J, Rentsch J: Quantification of meat proportions by measuring DNA contents in raw and boiled sausages using matrix-adapted calibrators and multiplex real-time PCR. J AOAC Int. 2012, 95 (2): 494-499.

Oakenfull EA, Clegg JB: Phylogenetic relationships within the genus Equus and the evolution of alpha and theta globin genes. J Mol Evol. 1998, 47 (6): 772-783.

Teletchea F, Bernillon J, Duffraisse M, Laudet V, Hanni C: Molecular identification of vertebrate species by oligonucleotide microarray in food and forensic samples. J Appl Ecol. 2008, 45 (3): 967-975.

Plohl M, Luchetti A, Mestrović N, Mantovani B: Satellite DNAs between selfishness and functionality: structure, genomics and evolution of tandem repeats in centromeric (hetero)chromatin. Gene. 2008, 409 (1–2): 72-82.

Chiang YC, Tsen HY, Chen HY, Chang YH, Lin CK, Chen CY, Pai WY: Multiplex PCR and a chromogenic DNA macroarray for the detection of Listeria monocytogens, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae, Enterobacter sakazakii, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Salmonella spp. and Pseudomonas fluorescens in milk and meat samples. J Microbiol Methods. 2012, 88 (1): 110-116.

Chen C-C, Hsia K-C, Huang C-T, Wong W-W, Yen M-Y, Li L-H, Lin K-Y, Chen K-W, Li S-Y: Draft genome sequence of a dominant, multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain, TCDC-NG08107, from a sexual group at high risk of acquiring human immunodeficiency virus infection and syphilis. Bacteriol. 2011, 193 (7): 1788-1789.

Schubert-Ullrich P, Rudolf J, Ansari P, Galler B, Führer M, Molinelli A, Baumgartner S: Commercialized rapid immunoanalytical tests for determination of allergenic food proteins: an overview. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009, 395 (1): 69-81.

Adey A, Morrison HG, Xun X, Kitzman JO, Turner EH, Stackhouse B, MacKenzie AP, Caruccio NC, Zhang X, Shendure J, Asan: Rapid, low-input, low-bias construction of shotgun fragment libraries by high-density in vitro transposition. Genome Biol. 2010, 11 (12): R119-

Mafra I, Ferreira I, Oliveira M: Food authentication by PCR-based methods. Eur Food Res Technol A. 2008, 227 (3): 649-665.

van Nieuwerburgh F, Soetaert S, Podshivalova K, Ay-Lin Wang E, Schaffer L, Deforce D, Salomon DR, Head SR, Ordoukhanian P: Quantitative bias in Illumina TruSeq and a novel post amplification barcoding strategy for multiplexed DNA and small RNA deep sequencing. PloS One. 2011, 6 (10): e26969-

Kircher M, Sawyer S, Meyer M: Double indexing overcomes inaccuracies in multiplex sequencing on the Illumina platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40 (1): e3-

Segata N, Waldron L, Ballarini A, Narasimhan V, Jousson O, Huttenhower C: Metagenomic microbial community profiling using unique clade-specific marker genes. Nat Methods. 2012, 9 (8): 811-814.

Wood DE, Salzberg SL: Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 2014, 15 (3): R46-

Francis OE, Bendall M, Manimaran S, Hong CJ, Clement NL, Castro-Nallar E, Snell Q, Schaalje GB, Clement MJ, Crandall KA, Johnason WE: Pathoscope: Species identification and strain attribution with unassembled sequencing data. Genome Res. 2013, 23 (10): 1721-1729.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding by the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz Center for Computational Sciences (SRFN; to TH and BS), the JGU Mainz intramural funding program and the Ministry of Justice and for Consumer Safety Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany (to TH). The authors also thank Dr. Steffen Rapp (JGU Mainz) and Dr. Sven Bikar (GENterprise & StarSEQ GmbH, Mainz) for operation of the Illumina sequencers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TH, FR, FK, MW and RK conceived the study. FR, FK, AS and MW evaluated datasets. YL and BS improved AFS routines and benchmarked datasets. RK contributed DNA material and unpublished food-related data. TH, FR and FK drafted the manuscript. YL, BS, RK and MW revised the manuscript. All authors approved the paper in its final version.

Fabian Ripp, Christopher Felix Krombholz contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ripp, F., Krombholz, C.F., Liu, Y. et al. All-Food-Seq (AFS): a quantifiable screen for species in biological samples by deep DNA sequencing. BMC Genomics 15, 639 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-639

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-639