Abstract

Background

Melon, Cucumis melo, and cucumber, C. sativus, are among the most widely cultivated crops worldwide. Cucumis, as traditionally conceived, is geographically centered in Africa, with C. sativus and C. hystrix thought to be the only Cucumis species in Asia. This taxonomy forms the basis for all ongoing Cucumis breeding and genomics efforts. We tested relationships among Cucumis and related genera based on DNA sequences from chloroplast gene, intron, and spacer regions (rbcL, matK, rpl20-rps12, trnL, and trnL-F), adding nuclear internal transcribed spacer sequences to resolve relationships within Cucumis.

Results

Analyses of combined chloroplast sequences (4,375 aligned nucleotides) for 123 of the 130 genera of Cucurbitaceae indicate that the genera Cucumella, Dicaelospermum, Mukia, Myrmecosicyos, and Oreosyce are embedded within Cucumis. Phylogenetic trees from nuclear sequences for these taxa are congruent, and the combined data yield a well-supported phylogeny. The nesting of the five genera in Cucumis greatly changes the natural geographic range of the genus, extending it throughout the Malesian region and into Australia. The closest relative of Cucumis is Muellerargia, with one species in Australia and Indonesia, the other in Madagascar. Cucumber and its sister species, C. hystrix, are nested among Australian, Malaysian, and Western Indian species placed in Mukia or Dicaelospermum and in one case not yet formally described. Cucumis melo is sister to this Australian/Asian clade, rather than being close to African species as previously thought. Molecular clocks indicate that the deepest divergences in Cucumis, including the split between C. melo and its Australian/Asian sister clade, go back to the mid-Eocene.

Conclusion

Based on congruent nuclear and chloroplast phylogenies we conclude that Cucumis comprises an old Australian/Asian component that was heretofore unsuspected. Cucumis sativus evolved within this Australian/Asian clade and is phylogenetically far more distant from C. melo than implied by the current morphological classification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Knowing the closest relatives and natural composition of the genus Cucumis L. is important because of ongoing efforts by plant breeders worldwide to improve melon (C. melo) and cucumber (C. sativus) with traits from wild relatives [1]. Next to tomatoes and onion, melon and cucumber may be the most widely cultivated vegetable species in the world [2]. Economic interest from breeders also led to the sequencing of the complete chloroplast genome of C. sativus [3]. Evolutionarily, Cucumis organellar genomes are unusually labile [4–7], and major chromosome rearrangements are thought to have taken place during the evolution of Cucumis. Cucumis sativus is the only species in the genus with a chromosome number of n = 7, which is thought to have evolved from a presumed ancestral karyotype with n = 12, but details of this reduction in chromosome number have remained unclear. Thus, the genus Cucumis holds great interest as a system in which to study the evolution of organellar and nuclear genomes, and there are also several ongoing efforts to map the genomes of C. melo and C. sativus [8].

Ongoing work on Cucurbitales and Cucurbitaceae [9, 10] has resulted in the generation of sequence data for a dense sample of taxa that together represent 21% of the family's 800 species and 95% of its 130 genera (following the most recent classification, 11]. Early results from this work suggested that Cucumis might not be monophyletic. We sought to test the monophyly of Cucumis by analyzing a broad sample of taxa based on Kirkbride's biosystematic monograph of the genus [12], other recent studies [10, 13], and geographical considerations (independent of traditional assessments of morphology). Robust phylogenetic trees for Cucumis might also shed light on the ancestral areas of C. melo and C. sativus. It is thought that C. sativus originated and was domesticated in Asia, while C. melo is though to have originated in eastern Africa [14], but with secondary centers of genetic diversity in the Middle East and India [15] and perhaps also China [16]. The center of Cucumis evolution is thought to be Africa [12].

The circumscription of Cucumis dates back to Linnaeus [17], with the most significant modern change being the separation of Cucumella Chiovenda in 1929, which has become generally accepted [11–13, 18]. The two genera differ only in the shape of their thecae, those of Cucumella being straight or slightly curved, those of Cucumis strongly curved and folded. Within the genus Cucumis, two subgenera are generally accepted, subgenus Melo (30 species, including C. melo), with most species in Africa and a chromosome n = 12, and subgenus Cucumis (2 species, C. sativus and C. hystrix), which is confined to Asia and has chromosome numbers of n = 12 and n = 7 [12, 19].

Molecular phylogenetic studies of Cucumis have sampled up to 16 species of Cucumis for chloroplast restriction sites and nuclear isozymes, nuclear ribosomal DNA from the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, microsatellite markers, and a combination of RAPDs and chloroplast markers [1, 20–22]. With one exception, these studies included only recognized species of Cucumis. A further handicap was that the sister group of Cucumis was unknown, so that trees could not be rooted reliably. Only Garcia-Mas et al. [22] sampled a potential relative, Oreosyce africana, material of which they received under the name Cucumis membranifolius Hook. f. and found embedded among species of Cucumis (see Results and Discussion for a problem with the identification of this material). Morphological similarities, however, argue for adding more representatives from African and Asian genera to phylogenetic analyses of Cucumis. Besides Cucumella, Dicaelospermum C. B. Clarke, Mukia Arn., Muellerargia Cogn., Myrmecosicyos C. Jeffrey, and Oreosyce Hook. all share key traits with Cucumis [summarized in [23]]. The most recent morphology-based classification of Cucurbitaceae [11] includes five more genera in the tribe Cucumerinae, to which Cucumis belongs. No representatives of Cucumerinae were included in previous molecular studies of Cucumis.

Because of the doubtful morphological separation from its supposed closest relative, Cucumella [12, 13, 18], and the insufficient sampling of other potentially related genera, the status of Cucumis as a monophyletic genus has remained equivocal. Here we address the three questions, Is Cucumis monophyletic? What is the closest relative of Cucumis? And what are the closest relatives of cucumber and melon?, using a two-pronged approach that involves chloroplast sequence data for all relevant genera of Cucurbitaceae and combined nuclear and chloroplast data for species of Cucumis, Cucumella, Dicaelospermum, Mukia, Muellerargia, Myrmecosicyos, and Oreosyce. Analysis of the combined data unexpectedly revealed that a monophyletic Cucumis lineage includes an Australian/Asian clade in which cucumber, C. sativus, is nested. This then raised the questions about the timing of the Australian connections, which we address with molecular clock dating.

Results and Discussion

The non-monophyly of Cucumis and why it remained undiscovered; comparison with earlier molecular phylogenies

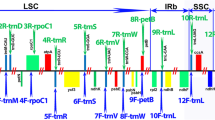

Parsimony (MP) and maximum likelihood (ML) analyses of combined sequences from the chloroplast genes rbcL and matK, the chloroplast intron trnL, and the spacers rpl20-rps12 and trnL-F, under the GTR + G + I model yielded a topology (Fig. 1) that was congruent with that obtained from the nuclear internal transcribed spacer region (Fig. 2). Chloroplast and nuclear data were therefore combined, and a parsimony tree from the combined data with MP and ML bootstrap support is shown as Fig. 3 (seven of the species lack ITS sequences, Table 1). In the family-wide analysis (with 123 of 130 genera of Cucurbitaceae sequenced), Cucumis is sister to Muellerargia (Fig. 4). The genera Cucumella, Dicaelospermum, Mukia, Myrmecosicyos, and Oreosyce are embedded among species of Cucumis (Fig. 3). The remaining genera of Cucumerinae sensu C. Jeffrey [11], Cucumeropsis Naudin, Melancium Naudin, Melothria L., Posadaea Cogn., and Zehneria Endl. (plus Neoachmandra and Scopellaria [24]) group far from Cucumis (Fig. 4). This fits with their geographic concentration in the New World (where Cucumis is absent): Melancium is a monotypic genus from Brazil, Posadaea a monotypic genus from tropical America, and Melothria has ten species in Central America and South America. However, Cucumeropsis, with a single species from tropical Africa, and Zehneria, Neoachmandra, and Scopellaria, with 66 species in tropical and subtropical Africa, Madagascar, Asia, New Guinea, and Australia [24] overlap with the natural range of Cucumis.

Maximum likelihood tree for Cucumis based on combined sequences from chloroplast genes, introns, and a spacer (details see Table 1). The tree is rooted on Muellerargia, the closest relative of Cucumis, based on the family phylogeny shown in Fig. 4. Parsimony bootstrap values (> 85%) based on 1000 replicates above branches and ML bootstrap values from 100 replicates below branches.

Parsimony tree for Cucumis based on sequences from the nuclear internal transcribed spacer, rooted on Muellerargia as in Fig. 1. Bootstrap values (> 65%) at branches are based on 1000 replicates. The genera marked with red lines are nested in Cucumis, and their species will need to be transferred to make Cucumis monophyletic. Species with the letters GM (Garcia-Mas) are from [22], while species labeled HS were generated for this study. The GenBank sequence labeled '?Oreosyce africana?' is from misidentified material (see text).

Parsimony tree for Cucumis based on the combined chloroplast and nuclear data and rooted on Muellerargia as in Fig. 1. Parsimony bootstrap values (> 75%) based on 1000 replicates above branches and ML bootstrap values from 100 replicates below branches. Species on pale grey background occur in Africa (C. prophetarum extends into India); the clade marked in grey-green occurs in Australia, the Malaysian region, Indochina, China, and India (Mukia maderaspatana extends into the Yemen and sub-Saharan Africa; see Table 1 for geographic ranges); the natural range of melon (C. melo) is unclear. Information on chromosome numbers is from the Index to Plant Chromosome Numbers database available online at the Missouri Botanical Garden's web site.

Detail of one of highest global likelihood trees for Cucurbitaceae obtained from combined chloroplast sequences (matK, rbcL, the trnL intron and spacer, and the rpl20-rps12 spacer; 4,966 aligned nucleotides; GTR + G), with parsimony bootstrap values based on 100 replicates shown at branches. Modified from 10, which contains the full tree with all 123 genera. Highlighted are the Cucumis clade and the genera of Cucumerinae in the most recent morphological classification (11).

The sister genus to Cucumis, Muellerargia, consists of one species in Madagascar and one in Indonesia and Queensland. Both are herbaceous trailers or climbers with straight or apically reflexed anthers and softly spinose fruits. Muellerargia has never been recognized as closely related to Cucumis [12, 25], perhaps because it is extremely poorly collected, with but a few specimens even in major herbaria: The Madagascan species, Muellerargia jeffreyana Keraudren, is known from three collections (in the Paris herbarium), and permission was not granted to sacrifice material for this study. It is morphologically similar to the Indonesian-Australian species M. timorensis Cogn. [26]. The poor documentation of the genus in herbaria also led to the Australian species being described at least three times; first as Muellerargia timorensis Cogn., then as Melothria subpellucida Cogn., and then as Zehneria ejecta Bailey (syn. Melothria ejecta (Bailey) Cogn.).

The Cucumis species relationships found here differ from those found in earlier studies [1, 20–22]. An unrooted nuclear isozyme tree [21] showed C. sativus as the genetically most distant species, while C. melo was sister to an African clade. The neighbor-joining tree from nuclear ITS sequences of Garcia-Mas et al. [22] was rooted on Citrullus lanatus and Cucurbita pepo, and showed C. sativus as the first-branching species in the genus, while C. melo was sister to a large African clade. Finally, the chloroplast tree of Chung et al. [1] also was rooted on Citrullus and showed C. sativus and C. hystrix as sister to C. melo (as did studies focusing on C. sativus; e.g., [27]). By contrast, the data presented here (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4) indicate that (i) the deepest divergence in Cucumis is between C. hirsutus and C. humifructus on the one hand and all other species on the other, (ii) C. sativus (cucumber) and C. hystrix are closer to Dicaelospermum and Mukia than they are to any species of Cucumis, and (iii) C. melo (melon) is sister to a clade comprising Dicaelospermum, Mukia, C. sativus, C. hystrix, and a new species from Australia (HS414).

There are several possible explanations for the contrasting findings of the earlier phylogenetic studies. First, the use of distant outgroups might have "attracted" the long-branched (i.e., mutation-rich) C. sativus, pulling it to the base of the tree. Garcia-Mas et al. [22] and Chung et al. [1] used Citrullus lanatus and/or Cucurbita pepo as sole outgroups. Both taxa are many clades, and millions of years of evolution, removed from the Cucumis clade (Fig. 4) and therefore add long branches to neighbor-joining and parsimony analyses [1, 22]. The inclusion of these long branches could have caused long-branch attraction between them and C. sativus.

A second reason why previous molecular phylogenetic studies were unable to test the monophyly of Cucumis and to infer the sister clades of cucumber and melon is that they did not include a sufficiently broad sample of taxa. For example, rigidly testing the monophyly of Cucumis section Melo required sequencing all of its species, C. melo, C. hirsutus, C. humifructus, and C. sagittatus. Results (Figs. 1, 2, 3) show that C. hirsutus and C. humifructus, rather than being close to C. melo, are sister to all other species of Cucumis sensu lato, that is, including all five genera nested in Cucumis.

Another possible reason for apparent differences between earlier topologies and the phylogeny found here is insufficient signal in the data and misidentified material. Comparison of the ITS sequences of Garcia-Mas et al. [22] to our ITS sequences showed that the sequence labeled Cucumis membranifolius in GenBank (AJ488223) and Oreosyce africana in the published paper (these names refer to the same species fide [12]), does not represent Oreosyce africana. The sequence came from a seed provided by the North Central Regional Plant Introduction Station in Ames, Iowa, and since there is no voucher, its identification cannot be verified. We also could not reproduce the topology and bootstrap support obtained in the original paper [22], partly probably because the phylogenetic signal in the data is weak, resulting in many equally likely trees. Garcia-Mas et al. [22] included sequences resulting from direct sequencing as well as sequences obtained by pGEM-T Easy Vector cloning and found sequences from multiple accessions generally grouping by species. Our Cucumis ITS sequencing confirmed these authors' assessment that ITS lineage sorting is not a problem in Cucumis. The two C. ficifolius sequences obtained by Garcia-Mas et al. [22] that do not group (Fig. 2) come from different plants and may simply represent different species; however, since the material is unvouchered, the identifications cannot be checked.

Implications for the evolution and biogeography of Cucumis

The phylogeny from the combined nuclear and chloroplast data (Fig. 3) implies that the deepest divergence lies between the common ancestor of C. hirsutus and C. humifructus and the stem lineage of the remainder of the genus. From the geographic ranges of the species of Cucumis sensu lato (i.e., the natural clade identified here) and its sister genus Muellerargia (with one species in tropical Australia and Indonesia, the other in Madagascar), the area where Cucumis may have originated cannot reliably be inferred. Strict and semi-parametric molecular clocks indicated that the deepest divergence in Cucumis may date back to 48–45 my and that the split between the C. melo lineage and its Australian/Asian sister clade is only slightly younger. The divergence of C. sativus from C. hystrix may be about 8 my old and that of their common ancestor from the ancestor of Dicaelospermum and Mukia maderaspatana about 19 my. The bulk of the African species appears to have evolved more recently. The absence of a fossil constraint within Cucumis, however, cautions against over-confidence in the molecular clock estimates.

Based on the tree (Fig. 3), the earliest divergence events in Cucumis likely took place in Africa. However, contrary to the traditional classification [12], which groups C. melo with the African C. hirsutus, C. humifructus, and C. sagittatus, melon is closest to an Australian/Asian clade (marked in grey-green in Fig. 3) that comprises an undescribed Australian species [28], species currently placed in Mukia (M. javanica, M. maderaspatana), Dicaelospermum ritchiei from Western India (recently transferred to Mukia [29]), and Cucumis sativus and C. hystrix from India, China, Burma, and Thailand. In addition to the two species we sequenced, Mukia comprises three others [29], its overall geographic range extending from Indo-China southeast to Java, Borneo, and the Philippines, and west through India, Pakistan, and the Yemen into sub-Saharan Africa. Given the geographic distribution of its extant closest relatives (Fig. 3), C. melo itself could have originated somewhere in Asia and then reached Africa from there, rather than originating in Africa as traditionally assumed [14, 15]. Notably, Indian melon landraces exhibit the largest isozyme variation among Asian melons [16] and Australia is a center of complex morphological variation of C. melo [28].

The evolution of morphological traits relevant for Cucumis breeders, for example fruit type, habit, and sexual system, will need to be reinterpreted based on the phylogenetic relationships presented here. Most of the 52 described species in the Cucumis clade are monoecious perennials, and the monoecious sexual system and perennial habit may be the ancestral condition from which an annual habit and dioecy appear to have evolved several times. However, the sexual system and habit of key taxa, such as Dicaelospermum, Muellerargia, and the as yet undescribed species from Australia [28] (Fig. 3) are not reliably known because species are under-collected and have not been studied in the field. Of the 17 species of Cucumis not yet sequenced, most are monoecious perennials; only C. kalahariensis A. Meeuse and C. rigidus Sond. are dioecious and perennial. Species currently placed in Mukia [29] and Cucumella [13] are mostly monoecious and perennial. The evolution of smooth fruits from spiny fruits, a traditional key character in Cucumis, and the mode of fruit opening are much more plastic than formerly thought. For example, in Oreosyce africana and Muellerargia timorensis the fruits open explosively [[30]; I. Telford, Beadle Herbarium, Armidale, personal communication, Feb. 2007); in C. humifructus, fruits mature below ground and are then dug up and the seeds dispersed by antbears, Orycteropus afer [31]; in the new species from Australia (HS414 in Figs. 1 and 2), the developing fruit is pushed into rock crevices by the elongating pedicel and also matures below ground; and in Myrmecosicyos messorius the fruits are tiny and apparently dispersed by harvesting ants around whose nest entrances the species grows.

Conclusion

Based on congruent nuclear and chloroplast phylogenies we conclude that a monophyletic Cucumis comprises an old Australian/Asian clade that includes cucumber and at least eight other species, most of them currently placed in Mukia. The new insights about the closest relatives of melon and cucumber have implications for ongoing genomics efforts. It is known that Cucumis organellar genomes are unusually labile. Thus, in C. sativus, rbcL has been transferred from the plastome to the mitochondrial genome [4], and huge amounts of degenerate repetitive DNA have accumulated in C. sativus mitochondria [5–7]. The seven meiotic chromosomes of C. sativus are larger than the 12 of its wild sister species or progenitor C. hystrix [32] and consist of six metacentrics and one submetacentric chromosome [33]. To infer the genome rearrangements that must have taken place during the evolution and domestication of C. sativus, analyses of co-linearity will be required between the cucumber lineage and its closest relatives Dicaelospermum ritchiei and species of Mukia. Finally, the possibility that C. melo may have evolved in Asia and reached Africa secondarily needs to be tested.

Methods

Taxon Sampling and Data Sets Analyzed

Table 1 lists all species sampled with authors, status as generic types where applicable, plant sources, and GenBank accession numbers [TreeBASE: study accession S1604, matrix accession M2887, M3250 and M3251]; 79 chloroplast and 20 ITS sequences were newly generated for this study. Species concepts and generic assignments throughout this study follow recent classifications [11–13, 29], although as a result of this study, species in several genera have been transferred into Cucumis ([34]; this also provides a morphological key to the 52 described species). To resolve species relationships within Cucumis, we added sequences from the nuclear internal transcribed spacer region (220 nt of ITS 1, 163 nt of the 5.8S gene, and 240 nt of ITS 2) for the same species for which chloroplast data were generated. DNA extraction, purification, and sequencing of the selected loci followed standard procedures [10]. All PCR products were sequenced in both directions. Direct PCR amplification of ITS yielded single bands and unambiguous base calls, except in C. ficifolia, the sequences of which were therefore not used. Sequences were edited and assembled with the Sequencher software (Gene Codes) and aligned by eye, using MacClade [35]. The aligned chloroplast matrix comprised 4,375 positions after exclusion of a poly-T run in the matK gene, a poly-A run in the trnL intron, a TATATA microsatellite region in the trnL-F intergenic spacer and a poly-A run in the rpl20-rps12 intergenic spacer. The aligned ITS matrix comprised 677 aligned positions, and we excluded a poly-G stretch of 25 nt and a poly-C stretch of 17 nt from the ITS1 and a poly-C stretch of 11 nt from ITS2.

Phylogenetic Analyses

Equally weighted parsimony analyses were conducted using PAUP 4.0b10 [36]. The search strategy involved 100 random taxon addition replicates with tree-bisection-reconnection branch swapping, MulTrees and Steepest Descent in effect, no limit on trees in memory, and saving all optimal trees. For MP analyses, gaps were treated as missing data, while for ML searches (below) they were mostly removed. To assess node support, parsimony bootstrap analyses were performed using 1000 replicate heuristic searches, each with 10 random addition replicates and otherwise the same settings as used for tree searches. More computationally intensive heuristic approaches have been found not to increase the reliability of bootstrapping [37]. Maximum likelihood analyses and bootstrapping were performed using GARLI 0.951 [38]. GARLI searches relied on the GTR + G + P-invar model, which ModelTest 3.06 [39] selected as the best fitting model for the combined data. Parameters were estimated over the duration of specified runs.

Molecular clock dating

Molecular clock dating in Cucurbitaceae is problematic because of the family's scarce fossil record. Without multiple calibrations, such as could come from several securely assigned fossils, relaxed molecular clock methods have been shown to perform poorly [40–42]. We therefore relied on a strict clock approach and compared it with results obtained with the semi-parametric penalized likelihood approach [40] implemented in r8s vs. 1.7). For strict clock dating, we employed the maximum likelihood topology obtained (under GTR + G) with the family data set of Kocyan et al. [10] augmented by the Cucumis sequences generated for this study for a total of 193 taxa and 5,028 aligned nucleotide positions. The tree was imported into PAUP [36], rooted on Corynocarpaceae, and rbcL branch lengths were then calculated under a GTR + G + I + strict clock model. Branch lengths were saved and a mutation rate obtained by dividing the distance from the most recent common ancestor (mrca) of Trichosanthes to the present (0.01416) by 65 my, based on the oldest seeds assigned to this genus [43]. Using the resulting rate of 0.000218 substitutions/site/my, we obtained an age of 47.6 my for the mrca of Cucumis by dividing the distance from the basal divergence in Cucumis to the present (0.01037) by 0.000218. The time of the divergence of C. melo from its sister clade was calculated accordingly (0.00975 : 0.000218 = 44.7 my). To check this strict clock estimate based on rbcL, we imported the 193-taxon-ML tree with branch lengths from the combined chloroplast data (5,028 nt) into r8s and ran a cross validation analysis, using the following upper and lower temporal constraints. The mrca of the family Cucurbitaceae was constrained to maximally 100 my and minimally 65 my old based on Cucurbitales family relationships and fossil records [9, 43]; the mrca of Trichosanthes was constrained to minimally 65 my [42]; and the mrca of an endemic clade of two species occurring on Hispaniola was constrained to maximally 30 my old based on the oldest ages of Dominican amber [44]. Penalized likelihood yielded an age of 44.9 my for the mrca of Cucumis.

Abbreviations

- ML:

-

maximum likelihood

- MP:

-

maximum parsimony

- mrca:

-

most recent common ancestor

- my:

-

million years

- nt:

-

nucleotide.

References

Chung S-M, Staub JE, Chen J-F: Molecular phylogeny of Cucumis species as revealed by consensus chloroplast SSR marker length and sequence variation. Genome. 2006, 49: 219-229. 10.1139/G05-101.

Pitrat M, Chauvet M, Foury C: Diversity, history, and production of cultivated cucurbits. Acta Hort. 1999, 492: 21-28.

Kim JS, Jung JD, Lee JA, Park HW, Oh KH, Jeong WJ, Choi DW, Liu JR, Cho KY: Complete sequence and organization of the cucumber (Cucumis sativus L. cv. Baekmibaekdadagi) chloroplast genome. Plant Cell Rep. 2006, 25: 334-340. 10.1007/s00299-005-0097-y.

Cummings MP, Nugent JM, Olmstead RG, Palmer JD: Phylogenetic analysis reveals five independent transfers of the chloroplast gene rbcL to the mitochondrial genome in angiosperms. Curr Genet. 2003, 43: 131-138.

Bendich AJ, Anderson RS: Novel properties of satellite DNA from muskmelon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974, 71: 1511-1515. 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1511.

Ward BL, Anderson RS, Bendich AJ: The mitochondrial genome is large and variable in a family of plants (Cucurbitaceae). Cell. 1981, 25: 793-803. 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90187-2.

Lilly JW, Havey MJ: Small, repetitive DNAs contribute significantly to the expanded mitochondrial genome of cucumber. Genetics. 2001, 159: 317-328.

Ritschel PS, de Lima Lins TC, Tristan RL, Cortopassi-Buso GS, Amauri-Buso J, Ferreira ME: Development of microsatellite markers from an enriched genomic library for genetic analysis of melon (Cucumis melo L.). BMC Plant Biology. 2004, 4: 9-10.1186/1471-2229-4-9.

Zhang L-B, Simmons MP, Kocyan A, Renner SS: Phylogeny of the Cucurbitales based on DNA sequences of nine loci from three genomes: implications for morphological and sexual system evolution. Mol Phyl Evol. 2006, 39: 305-322. 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.10.002.

Kocyan A, Zhang L-B, Schaefer H, Renner SS: A multi-locus chloroplast phylogeny for the Cucurbitaceae and its implications for character evolution and classification. Mol Phyl Evol. 2007,

Jeffrey C: A new system of Cucurbitaceae. Bot Zhurn. 2005, 90: 332-335.

Kirkbride JH: Biosystematic monograph of the genus Cucumis (Cucurbitaceae). 1993, Boone, NC: Parkway Publishers

Kirkbride JH: Revision of Cucumella (Cucurbitaceae, Cucurbitoideae, Melothrieae, Cucumerinae). Brittonia. 1994, 46: 161-186. 10.2307/2807230.

Whitaker TW, Davis GN: Cucurbits – Botany, Cultivation, Utilization. 1996, New York: Interscience Publ

Robinson RW, Decker-Walters DS: Cucurbits. (Crop Production Science in Horticulture no. 6). 1997, New York: Cab International

Akashi Y, Fukuda N, Wako T, Masuda M, Kato K: Genetic variation and phylogenetic relationships in East and South Asian melons, Cucumis melo L., based on the analysis of five isozymes. Euphytica. 2002, 125: 385-396. 10.1023/A:1016086206423.

Linnaeus C: Species plantarum. 1735, Stockholm, Impensis Laurentii Salvii, 1

Jeffrey C: Notes on Cucurbitaceae, including a proposed new classification of the family. Kew Bull. 1962, 15: 337-371.

Chen J-F, Staub JE, Tashiro Y, Isshiki S, Miyazaki S: Successful interspecific hybridization between Cucumis sativus L. and C. hystrix Chakr. Euphytica. 1997, 96: 413-419. 10.1023/A:1003017702385.

Perl-Treves R, Galun E: The Cucumis plastome: physical map, intrageneric variation and phylogenetic relationships. Theor Appl Genet. 1985, 71: 417-429.

Perl-Treves R, Zamir D, Navot N, Galun E: Phylogeny of Cucumis based on isozyme variability and its comparison with plastome phylogeny. Theor Appl Genet. 1985, 71: 430-436.

Garcia-Mas J, Monforte AJ, Arús P: Phylogenetic relationships among Cucumis species based on the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer sequence and microsatellite markers. Plant Syst Evol. 2004, 248: 191-203. 10.1007/s00606-004-0170-y.

Jeffrey C: A review of the Cucurbitaceae. Bot J Linn Soc. 1980, 81: 233-247.

De Wilde WJJO, Duyfjes BEE: Redefinition of Zehneria and four new related genera (Cucurbitaceae), with an enumeration of the Australasian and Pacific species. Blumea. 2006, 51: 1-88.

Müller EGO, Pax F: Cucurbitaceae. Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien nebst ihren Gattungen und wichtigeren Arten insbesondere den Nutzpflanzen. Edited by: Engler A, Prantl K. 1889, Leipzig: W. Engelmann, IV, 5 (34): 1-39.

Keraudren M: Présence du genre indonésien Muellerargia (Cucurbitaceae) a Madagascar. Adansonia. 1965, 5: 421-424.

Zhuang F-Y, Chen J-F, Staub JE, Qian C-T: Taxonomic relationships of a rare Cucumis species (C. hystrix Chakr.) and its interspecific hybrid with cucumber. Hortscience. 2006, 41: 571-574.

Telford IR: Cucurbitaceae. Fl. Australia 8. 1982, 205: 158-198.

De Wilde WJJO, Duyfjes BEE: Mukia Arn. (Cucurbitaceae) in Asia, in particular in Thailand. Thai Forest Bull (Bot.). 2006, 34: 38-52.

Jeffrey C:Cucurbitaceae. Flora of Tropical East Africa. Edited by: Milne-Redhead, Polhill RM. 1967, London: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew,

Meeuse AJD: A possible case of interdependence between a mammal and a higher plant. Arch Néerl Zool. 1958, 314-318. 13 Suppl

Chen J-F, Luo X-D, Qian C-T, Jahn MM, Staub JE, Zhuang F-Y, Lou Q-F, Ren G: Cucumis monosomic alien addition lines: morphological, cytological, and genotypic analyses. Theor Appl Genet. 2004, 108: 1343-1348. 10.1007/s00122-003-1546-z.

Koo DH, Choi HW, Cho J, Hur Y, Bang JW: A high-resolution karyotype of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L. 'Winter Long') revealed by C-banding, pachytene analysis, and RAPD-aided fluorescence in situ hybridization. Genome. 2005, 48: 534-540. 10.1139/g04-128.

Schaefer H: Cucumis (Cucurbitaceae) must include Cucumella, Dicoelospermum, Mukia, Myrmecosicyos, and Oreosyce: a recircumscription based on nuclear and plastid DNA data. Blumea. 2007,

Maddison DR, Maddison WP: MacClade, version 4.05. 2003, Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates

Swofford DL: PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and other methods). 2002, Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates

Müller K: The efficiency of different search strategies in estimating parsimony jackknife, bootstrap, and Bremer support. BMC Evol Biol. 2005, 5: 58-10.1186/1471-2148-5-58.

Zwickl DJ: Genetic algorithm approaches for the phylogenetic analysis of large biological sequence datasets under the maximum likelihood criterion. 2006, . Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin

Posada D, Crandall KA: Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998, 14: 817-818. 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817.

Sanderson MJ: Estimating absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times: a penalized likelihood approach. Mol Biol Evol. 2002, 19: 101-109.

Pérez-Losada M, Høeg JT, Crandall KA: Unraveling the evolutionary radiation of the Thoracican barnacles using molecular and morphological evidence: a comparison of several divergence time estimation approaches. Syst Biol. 2004, 53: 244-264. 10.1080/10635150490423458.

Ho SY, Phillips MJ, Drummond AJ, Cooper A: Accuracy of rate estimation using relaxed-clock models with a critical focus on the early metazoan radiation. Mol Biol Evol. 2005, 22: 1355-1363. 10.1093/molbev/msi125.

Collinson ME, Boulter MC, Holmes PR: Magnoliophyta (Angiospermae). The Fossil Record 2. Edited by: Benton MJ. 1993, Chapman and Hall, London, 809-841, 864.

Iturralde-Vinent MA, MacPhee RDE: Age and paleogeographical origin of Dominican amber. Science. 1996, 273: 1850-1852. 10.1126/science.273.5283.1850.

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Decker-Walters, M. Wilkins, W. de Wilde, and I. Telford for silica-dried leaves and G. Hausner for comments on the manuscript. The German National Science Foundation (RE 603/3-1) supported fieldwork for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

SR, HS, and AK obtained the material, AK organized the sequencing and alignments for non-Cucumis Cucurbitaceae, HS did the sequencing and alignments for this study, and SR designed the project, performed molecular clock analyses, and wrote the manuscript. All authors ran tree searches, and all read and approved the final submission.

Susanne S Renner, Hanno Schaefer contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Renner, S.S., Schaefer, H. & Kocyan, A. Phylogenetics of Cucumis (Cucurbitaceae): Cucumber (C. sativus) belongs in an Asian/Australian clade far from melon (C. melo). BMC Evol Biol 7, 58 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-7-58

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-7-58