Abstract

Background

Mice lacking either colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) or its receptor, CSF-1R, display osteopetrosis. Accordingly, genetic deletion or pharmacological blockade of CSF-1 prevents the bone loss associated with estrogen deficiency. However, the role of CSF-1R in osteoporosis models of type-1 diabetes (T1D) and ovariectomy (OVX) has not been examined. Thus, we evaluated whether CSF-1R blockade would relieve the bone loss in a model of primary osteoporosis (female mice with OVX) and a model of secondary osteoporosis (female with T1D) using micro-computed tomography.

Methods

Female ICR mice at 10 weeks underwent OVX or received five daily administrations of streptozotocin (ip, 50 mg/kg) to induce T1D. Four weeks after OVX and 14 weeks after first injection of streptozotocin, mice received an anti-CSF-1R (2G2) antibody (10 mg/kg, ip; once/week for 6 weeks) or vehicle. At the last day of antibody administration, mice were sacrificed and femur and tibia were harvested for micro-computed tomography analysis.

Results

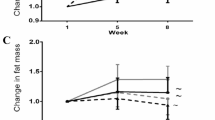

Mice with OVX had a significant loss of trabecular bone at the distal femoral and proximal tibial metaphysis. Chronic treatment with anti-CSF-1R significantly reversed the trabecular bone loss at these anatomical sites. Streptozotocin-induced T1D resulted in significant loss of trabecular bone at the femoral neck and cortical bone at the femoral mid-diaphysis. Chronic treatment with anti-CSF-1R antibody significantly reversed the bone loss observed in mice with T1D.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate that blockade of CSF-1R signaling reverses bone loss in two different mouse models of osteoporosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Watts NB, Investigators G. Insights from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(7):412–22.

Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, Curtis JR, Delzell ES, Randall S, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520–6.

Khosla S, Hofbauer LC. Osteoporosis treatment: recent developments and ongoing challenges. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(11):898–907.

Lutz W, Sanderson W, Scherbov S. The coming acceleration of global population ageing. Nature. 2008;451(7179):716–9.

Valderrabano RJ, Linares MI. Diabetes mellitus and bone health: epidemiology, etiology and implications for fracture risk stratification. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;4:9.

Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. Genetic regulation of osteoclast development and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4(8):638–49.

Stanley ER, Berg KL, Einstein DB, Lee PS, Pixley FJ, Wang Y, et al. Biology and action of colony–stimulating factor-1. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;46(1):4–10.

Ji MX, Yu Q. Primary osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2015;1(1):9–13.

Eastell R, O'Neill TW, Hofbauer LC, Langdahl B, Reid IR, Gold DT, et al. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16069.

Riggs BL, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Mazess RB, Offord KP, Melton LJ 3rd. Differential changes in bone mineral density of the appendicular and axial skeleton with aging: relationship to spinal osteoporosis. J Clin Invest. 1981;67(2):328–35.

Neumann T, Lodes S, Kastner B, Lehmann T, Hans D, Lamy O, et al. Trabecular bone score in type 1 diabetes a cross-sectional study. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(1):127–33.

Janghorbani M, Van Dam RM, Willett WC, Hu FB. Systematic review of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of fracture. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(5):495–505.

Hough FS, Pierroz DD, Cooper C, Ferrari SL, Bone IC, Diabetes WG. Mechanisms in endocrinology: mechanisms and evaluation of bone fragility in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174(4):R127–R138138.

Botolin S, Faugere MC, Malluche H, Orth M, Meyer R, McCabe LR. Increased bone adiposity and peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-gamma2 expression in type I diabetic mice. Endocrinology. 2005;146(8):3622–31.

Kayal RA, Tsatsas D, Bauer MA, Allen B, Al-Sebaei MO, Kakar S, et al. Diminished bone formation during diabetic fracture healing is related to the premature resorption of cartilage associated with increased osteoclast activity. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(4):560–8.

Stanley ER, Berg KL, Einstein DB, Lee PS, Yeung YG. The biology and action of colony stimulating factor. Stem Cells. 1994;12:15–24.

Pollard JW. Trophic macrophages in development and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(4):259–70.

El-Gamal MI, Al-Ameen SK, Al-Koumi DM, Hamad MG, Jalal NA, Oh CH. Recent advances of colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) kinase and its inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2018;61(13):5450–66.

Yao GQ, Wu JJ, Troiano N, Zhu ML, Xiao XY, Insogna K. Selective deletion of the membrane-bound colony stimulating factor 1 isoform leads to high bone mass but does not protect against estrogen-deficiency bone loss. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30(4):408–18.

Pixley FJ, Stanley ER. CSF-1 regulation of the wandering macrophage: complexity in action. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14(11):628–38.

Harris SE, MacDougall M, Horn D, Woodruff K, Zimmer SN, Rebel VI, et al. Meox2Cre-mediated disruption of CSF-1 leads to osteopetrosis and osteocyte defects. Bone. 2012;50(1):42–53.

Saini A, Liu YJ, Cohen DJ, Ooi BS. Hyperglycemia augments macrophage growth responses to colony-stimulating factor-1. Metabolism. 1996;45(9):1125–9.

Cenci S, Weitzmann MN, Gentile MA, Aisa MC, Pacifici R. M-CSF neutralization and egr-1 deficiency prevent ovariectomy-induced bone loss. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(9):1279–87.

Wang XF, Wang YJ, Li TY, Guo JX, Lv F, Li CL, et al. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibition prevents against lipopolysaccharide -induced osteoporosis by inhibiting osteoclast formation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;115:108916.

Enriquez-Perez IA, Galindo-Ordonez KE, Pantoja-Ortiz CE, Martinez-Martinez A, Acosta-Gonzalez RI, Munoz-Islas E, et al. Streptozocin-induced type-1 diabetes mellitus results in decreased density of CGRP sensory and TH sympathetic nerve fibers that are positively correlated with bone loss at the mouse femoral neck. Neurosci Lett. 2017;655:28–34.

Vargas-Munoz VM, Martinez-Martinez A, Munoz-Islas E, Ramirez-Rosas MB, Acosta-Gonzalez RI, Jimenez-Andrade JM. Chronic administration of Cl-amidine, a pan-peptidylarginine deiminase inhibitor, does not reverse bone loss in two different murine models of osteoporosis. Drug Dev Res. 2020;81(1):93–101.

Zhang Y, Cheng N, Miron R, Shi B, Cheng X. Delivery of PDGF-B and BMP-7 by mesoporous bioglass/silk fibrin scaffolds for the repair of osteoporotic defects. Biomaterials. 2012;33(28):6698–708.

Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Muller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(7):1468–86.

Ries CH, Cannarile MA, Hoves S, Benz J, Wartha K, Runza V, et al. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages with anti-CSF-1R antibody reveals a strategy for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(6):846–59.

Bouxsein ML, Myers KS, Shultz KL, Donahue LR, Rosen CJ, Beamer WG. Ovariectomy-induced bone loss varies among inbred strains of mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(7):1085–92.

Bazan JF. Genetic and structural homology of stem cell factor and macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Cell. 1991;65(1):9–10.

Miyazawa K, Williams DA, Gotoh A, Nishimaki J, Broxmeyer HE, Toyama K. Membrane-bound Steel factor induces more persistent tyrosine kinase activation and longer life span of c-kit gene-encoded protein than its soluble form. Blood. 1995;85(3):641–9.

Ladner MB, Martin GA, Noble JA, Nikoloff DM, Tal R, Kawasaki ES, et al. Human CSF-1: gene structure and alternative splicing of mRNA precursors. EMBO J. 1987;6(9):2693–8.

Lin H, Lee E, Hestir K, Leo C, Huang M, Bosch E, et al. Discovery of a cytokine and its receptor by functional screening of the extracellular proteome. Science. 2008;320(5877):807–11.

Sarma U, Edwards M, Motoyoshi K, Flanagan AM. Inhibition of bone resorption by 17beta-estradiol in human bone marrow cultures. J Cell Physiol. 1998;175(1):99–108.

Lea CK, Sarma U, Flanagan AM. Macrophage colony stimulating-factor transcripts are differentially regulated in rat bone-marrow by gender hormones. Endocrinology. 1999;140(1):273–9.

Kimble RB, Srivastava S, Ross FP, Matayoshi A, Pacifici R. Estrogen deficiency increases the ability of stromal cells to support murine osteoclastogenesis via an interleukin-1and tumor necrosis factor-mediated stimulation of macrophage colony-stimulating factor production. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(46):28890–7.

Liu W, Xu GZ, Jiang CH, Da CD. Expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and its receptor in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Curr Eye Res. 2009;34(2):123–33.

Yao GQ, Wu JJ, Ovadia S, Troiano N, Sun BH, Insogna K. Targeted overexpression of the two colony-stimulating factor-1 isoforms in osteoblasts differentially affects bone loss in ovariectomized mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296(4):E714–E720720.

Kamada M, Irahara M, Maegawa M, Ohmoto Y, Takeji T, Yasui T, et al. Postmenopausal changes in serum cytokine levels and hormone replacement therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(3):309–14.

D'Amelio P, Roato I, D'Amico L, Veneziano L, Suman E, Sassi F, et al. Bone and bone marrow pro-osteoclastogenic cytokines are up-regulated in osteoporosis fragility fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(11):2869–77.

Luo J, Quan J, Tsai J, Hobensack CK, Sullivan C, Hector R, et al. Nongenetic mouse models of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 1998;47(6):663–8.

Judex S, Garman R, Squire M, Busa B, Donahue LR, Rubin C. Genetically linked site-specificity of disuse osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(4):607–13.

Roberts BC, Giorgi M, Oliviero S, Wang N, Boudiffa M, Dall'Ara E. The longitudinal effects of ovariectomy on the morphometric, densitometric and mechanical properties in the murine tibia: a comparison between two mouse strains. Bone. 2019;127:260–70.

Martin LM, McCabe LR. Type I diabetic bone phenotype is location but not gender dependent. Histochem Cell Biol. 2007;128(2):125–33.

Raehtz S, Bierhalter H, Schoenherr D, Parameswaran N, McCabe LR. Estrogen deficiency exacerbates type 1 diabetes-induced bone tnf-alpha expression and osteoporosis in female mice. Endocrinology. 2017;158(7):2086–101.

Dai XM, Ryan GR, Hapel AJ, Dominguez MG, Russell RG, Kapp S, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood. 2002;99(1):111–20.

Bagi CM, DeLeon E, Ammann P, Rizzoli R, Miller SC. Histo-anatomy of the proximal femur in rats: impact of ovariectomy on bone mass, structure, and stiffness. Anat Rec. 1996;245(4):633–44.

Toh ML, Bonnefoy JY, Accart N, Cochin S, Pohle S, Haegel H, et al. Bone- and cartilage-protective effects of a monoclonal antibody against colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor in experimental arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(11):2989–3000.

MacDonald KP, Palmer JS, Cronau S, Seppanen E, Olver S, Raffelt NC, et al. An antibody against the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor depletes the resident subset of monocytes and tissue- and tumor-associated macrophages but does not inhibit inflammation. Blood. 2010;116(19):3955–63.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (the Mexican Nacional Council for Science and Technology) [CB-2014 240829, PDCPN-2015-01-191, and Apoyo para Actividades Científicas, Tecnológicas y de Innovación 2019-299535]. We deeply acknowledge to Carola H. Ries for her helpful support to achieve the antibody donation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JMJA, EMI and MBRR conceived the project. AMM, EMI, HFTR and MBRR performed the experiments. JMJA, RIAG and MBRR analyzed and interpreted the data. JMJA, AMM, EMI, MBRR, RIAG and HFTR wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript. JMJA obtained grant funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martínez-Martínez, A., Muñoz-Islas, E., Ramírez-Rosas, M.B. et al. Blockade of the colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor reverses bone loss in osteoporosis mouse models. Pharmacol. Rep 72, 1614–1626 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43440-020-00091-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43440-020-00091-5