Abstract

The article traces developments since the publication of John Reader’s Theology and New Materialism (2017) with the aim of establishing conceptual resources that link concerns for the environment with those for digital technology. Drawing on the work of Bruno Latour and Bernard Stiegler, it proposes they share a common concern to provide an ‘earthing’ or form of practical knowledge to shape the discourses in both fields. It then addresses the question of why it remains difficult to operationalize appropriate responses and the concepts of disinhibition (Latour and for Stiegler) and autoimmunity (Derrida) offer possible explanations. To counter these difficulties, the idea of a modest ethics and from within theology, the dynamic between proximity and distance and then panentheism are presented as solutions. Each links back to key ideas from New Materialism such as distributed agency and mini or local transcendences and the concept of God who is ‘beyond in the midst’. It may be that finding our bearings in order to steer a new direction for both environmental and digital challenges require the ‘profound inner conversion’ of which Pope Francis speaks in his (2015) Laudato Si.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Every author knows that whenever a book is completed, there are always loose ends or other strands of thought that remain to be developed or followed up when the occasion arises. Such is the case with Theology and New Materialism (Reader 2017) as it was written with a very specific objective in mind: that of beginning to scope a new conceptuality with which theology might begin to more effectively tackle the twin issues of environment and technology. In order to do this, a major focus was on ideas emerging from New Materialism, but it was never the intention to restrict discussion to those or to adopt them uncritically. In the book, I supplemented these with reference to the philosophical work of Bruno Latour (2007) and Stiegler (2015a, b) amongst others, and from within theology to the work of Catherine Keller (2015), John Caputo (2013), and Kearney and Zimmerman (2016). There was, however, a particular area that remained underdeveloped, that of possible links between the environmental and the digital. As much has already been written within theology about the environmental, the main emphasis in the book was on the digital, so establishing a conceptuality that spans both areas remains a concern.

Although this article will refer to some of the concepts used in the book, this is an opportunity to add to those concepts such as disinhibition, autoimmunity, a modest ethics and an interpretation of God as found in panentheism, that now seem of value in spanning that gap. It also needs to be said that, following the launch of the book in June 2017, a group evolved from those present that has continued to meetFootnote 1, and which also pursues many of these themes. As such, the original book and the meetings since attempt to continue the conversations and to explore other ideas and contributions. This article will be a drawing together of some of that work so far and is in some respects the result of this collective enterprise. The other discussion that has developed is that of the role of religion(s) in addressing or even providing antidotes to some of the difficulties identified in the fields of environment and digital technology, and some of those discussions will be reflected in this article. In the book, I call this alternative approach relational Christian realism.

To summarize, the new concepts that will be proposed in this article are the idea of disinhibition; that of autoimmunity; the programme for a modest ethics; the dynamic between proximity and distance, and then from within theology itself, the potential contributions of ideas stemming from panentheism. Each of these will be described and developed in turn, but first, it is necessary to recapitulate the key ideas from Theology and New Materialism (Reader 2017) itself and to explain the background to its publication.

Theology and New Materialism: Spaces of Faithful Dissent (Reader 2017)

In 2015, three of us published A Philosophy of Christian Materialism (Baker et al. 2015) in which we drew upon the philosophies of Deleuze, Latour and Badiou in order to establish an approach we call relational Christian realism. I subsequently co-wrote a chapter with Clayton Crockett in Religious Experience and New Materialism (Crockett and Reader 2016) in which we brought together ideas from relational Christian realism and New Materialism in the context of environmental issues. Other chapters in this book drew attention to certain weaknesses or areas for further development in recent theological appropriations of New Materialism. Notable amongst these were concerns about transcendence and a possible over-emphasis upon immanence; the extent to which human agency is undervalued by New Materialism, and then whether or not this general approach had any purchase upon political engagement. Theology and New Materialism is a direct response to these concerns and addresses them by incorporating concepts from relational Christian realism into the wider debate. It also proposes a new conceptuality which will enable theology and religious practice to respond more appropriately to environmental and technological concerns.

The relational Christian realism approach advocates a link back to the theological realism and philosophical theology of Tillich (1978) although this goes well beyond both with its concern for the non-human, and is therefore able to engage with environmental issues. It also raises the question of whether there is any definitive purpose or telos for creation as the human is entangled with the unknown and unpredictable futures of nature as a whole. In addition, it draws on insights and ideas from other disciplines and traditions and therefore eschews any theological imperialism. It operates on the assumption that all public debates always already contain values which need to be made explicit and articulated—what Latour (2004) calls matters of concern rather than matters of fact. Like Latour, relational Christian realism aims to reassemble such matters of concern slowly and carefully rather than resorting to grand statements or judgements. It emphasizes the rhizomatic nature of material religious practices so suggesting that religious practice is more significant than either belief or doctrine. Attention is given to the assemblages or machines in which the human is already entangled and implicated (including relationship with the non-human). Finally, political action takes place in the interstices or spaces and operates at both the micro and macro levels.

To offer a flavour of the main arguments in Theology and New Materialism, it is useful to summarize the central chapters. Chapter two addresses the challenge of redefining transcendence, one of the identified weaknesses of theological appropriations of New Materialism. This begins by referring back to Deleuze’s ontology of difference (2008) and his emphasis upon immanence as a starting point for relational Christian realism’s counterbalance to New Materialism. Relational Christian realism refers to the even less familiar ideas of Object Oriented Ontology and the notion of small transcendences (Harman 2010) and an understanding of God as virtual. It then examines the tension between the apophatic (what is often referred to as the mystical or beyond articulation) and the relational, as described by Keller (2015) and Kearney and Zimmerman (2016). Latour, again providing an alternative to more traditional interpretations of transcendence, talks about local transcendences and religion as the immediate and close to hand rather than being distant, hierarchical and remote. Returning to Keller, one of the crucial questions in this whole debate is can there be a direct path from the apophatic to the ethical? God as ‘Wholly Other’ could just as easily be beyond relation as accessible to relation. Hence relational Christian realism draws instead upon God as virtual and as the ‘beyond in the midst’ described by Bonhoeffer (1976). The chapter concludes with a return to Kearney and Zimmerman (2016) and his use of chora as womb, cave or chamber/space/receptacle with stronger links to the tradition and notions of hospitality and the mediating entanglements that might balance the crowd (relational) and the cloud (apophatic).

Chapter three focusses upon the issue of human agency, and the central question of what it means to be or become human. A criticism of New Materialism is that it moves too far away from the significance and role of the human with its emphasis upon the non-human; however, both New Materialism and relational Christian realism aim to add to rather than subtracting from understandings of the human. Philosophers engaged in this discussion include Braidotti on the posthuman (2013) and Bennett’s ‘vibrant matter’ (2010) which argues for the concept of distributive agency. This proposes that humans are always already entangled with other agents rather than acting as lone autonomous individuals. In this context, Bryant (2014) talks about ‘machines’ rather than assemblages, as ‘subjects’ do not have to be human but can be institutions, corporations, states or even technology. I argue that DeLanda’s assemblages and network theory (2011) along with Bryant (2014) seem more balanced as a view of distributed human agency. Relational Christian realism then uses Latour, talking about human–non-human relationships and Badiou (2003) on what it means to be a faithful subject as one already engaged in activity, so these are the preferred relational Christian realism responses to the general issue of human agency.

Chapter four examines the issue of a new enlightenment. Three central issues are those of autonomy, reason and progress. Relational Christian realism offers the contributions of distributive agency and a more plastic sense of individual autonomy. So, is the enlightenment then now deferred, distorted or discredited? The chapter moves on to introduce the work of Stiegler (2015a, b) with reference to his ideas on reason and unreason and his aim to retrieve the enlightenment using Deleuze and Simondon. With the dominance of digital technology, there is a danger that reason becomes rationalization and functions as instrumental reason in which the process of human becoming and socialization is distorted by consumer and commercial forces. The following chapter concludes with a discussion of Stiegler’s (2015a, b) use of the division between otium (the space of recreation and reflection) and negotium (the realm of commercial and military activity as ancient Rome perceived it) as a parallel with the tension between the apophatic and the relational.

Chapter six develops Stiegler’s (2013) contribution further on the key contemporary subject of technology offering practical examples of both positive and negative impacts. For instance, many young people are now digitally tethered and we know that the big Tech companies use algorithms to manipulate our purchasing habits. Stiegler argues that technology has always been part of the development of the human, but in control societies (Deleuze), human attention is captured in such a way as to short-circuit human care and trust. We respond too quickly to the instant demands made upon us by digital technology. Time itself then becomes the key issue as argued by Yuk Hui (2016) in his attempt to establish an ontology of the digital using Heidegger and Simondon. There is already a symbiosis between the human and the digital and the digital runs ahead of the human and shapes our responses from the future. Is a digital chora a possibility? All of the above focus on the relational rather than the apophatic, so one needs also to argue that spaces are about time as well as location.

The final chapter examines whether any of these ideas are to be encountered in contemporary religious practice. It concludes that there are constant tensions, for instance when those of faith cross boundaries to work together, as others of faith sometimes respond by sharpening those boundaries. Climate change is now often seen as a contemporary form of apocalyptic. The question which remains for both relational Christian realism and New Materialism may be that neither offers a comfortable or definitive vision of the future, but do we then have the necessary resources to live with uncertainty and contingency? This question recurs once we move beyond the original text into subsequent work and ideas.

Developments since Theology and New Materialism

Since the book launch in 2017, there have been translations of some major publications by both Latour and Stiegler and these have contributed further ideas relevant to the discussion of both the environmental and the digital. Latour’s Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime (2017) based on his Gifford Lectures of 2015, and then Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime (2018). The first volume of Stiegler’s Automatic Society: The Future of Work (2016) and then The Age of Disruption: Technology and Madness in Computational Capitalism (2019). In the spirit of relational Christian realism, these have provided more content for consideration than New Materialism publications during this period. Before bringing the discussion up to date, it is important to register these ideas.

Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime (Latour 2018)

Latour’s basic hypothesis is that we cannot understand the last 50 years unless we recognize the intimate connections between globalization, the deregulation that is essential to that process; the explosion of inequalities; the question of climate change and the elements of denial that now attend that. This is the New Climatic Regime in which the elites have concluded that ‘the earth no longer had enough room for them and for everyone else’ (2018: 1). This absence of a common world is now driving us crazy. This has echoes of Stiegler’s interpretation of the teenager mentioned in The Age of Disruption (2019) who has basically lost hope of life now having any meaning or the prospect of a shared future. To resist this, Latour proposes that we need to come down to earth, to land somewhere, to be able to get our bearings and orient ourselves. To do this, he intends to provide a map or scoping of where we are now in order to rebuild a public life. I note that if the objective can no longer be to develop or identify a shared ethical framework, then perhaps the alternative of a modest ethics requires instead points of reference or landmarks that at least enable us to orient ourselves and recognize where we are on the journey. There may not be an agreed destination, but at least some sense of taking our bearings with reference to certain values and concerns.

Trump’s attitude to the Paris Climate Accord and subsequent approach to both international relationships and the environment are supposedly symptomatic of this general understanding. Americans do not belong to the same earth as everyone else. As with Brexit in the UK, this is an attempt to cut loose from other nations and to go it alone. Attitudes towards immigration are another characteristic of this, with fears of climate change creating waves of migration in the near future combined with flows of people from the conflict in the Middle East. Where are they going to ‘land’ and make their home? In the meantime, there are growing numbers from within who are falling into this category as a result of inequalities and no longer ‘belong’ in the same ways as others more fortunate. They have been set adrift through internal political and welfare mechanisms. The basic right to feel safe and protected when under threat has been undermined (Latour 2018: 11).

One obvious reaction to this is of course a resort to nationalism and the popularist politics that so often accompanies it. One protects one’s own space or place when others appear to threaten or impinge. So, an attachment to one’s land or territory can be viewed as simply reactionary. But rather than either being for or against globalization or the local, Latour suggests that what matters is to register or maintain the maximum number of alternative ways of belonging to the world (2018: 16). There is a problem of both scale and lodging, with the planet being much too narrow and limited for the globe of globalization, but at the same time too big to remain within the narrow and limited borders of any locality whatsoever. How then can we find a place, or orient ourselves? How do we cope with the issue of limits?

The response of the elites to this, according to Latour, is to accept that there can be no overall answer which can encompass everyone, so the only strategy is to get rid of all the burdens of solidarity as quickly as possible. Deregulate, dismantle welfare structures, ignore or even exacerbate inequalities, deny that climate change is happening or that it is the result of human activity and construct a safe place where one can pull up the drawbridge. The earth is no longer somewhere to be shared. It can never be acknowledged that this is the approach for obvious reasons. Facts, scientific findings, and the previous norms of public discourse are also victims of this process. The infrastructure of public life has to be undermined in order to shore up this position and give it some credibility. There are instead many truths, hence, none at all, and the populace is bombarded with conflicting and contradictory stories in order to disorientate and confuse. We do not know who to believe any longer so we end up believing no one, even those who might be trustworthy. What do either reason or rationality mean in this context? As Latour says, we no longer inhabit the same world and there is a deficit of shared practice (2018: 25). This is a deliberate ploy.

What is also abandoned as a result of this is the objective of a common trajectory, either that determined by an established tradition or that of developments which move away from those, some form of enlightenment ambition. So, both progressives and reactionaries are undermined by this. The old markers of left and right, local and global and future or past no longer have any purchase. The attraction of Trump is that he has managed to harness this context to his own benefit: ‘Trumpian politics is not “post-truth” but post politics, a politics with no object, since it rejects the world that it claims to inhabit’ (2018: 38). Latour names the new place we now need to inhabit, ‘the Terrestrial’, as rather than being the framework for action it itself participates in that action. Humans are no longer the only actors, as the earth also now comes fully into play.

What, however, is an appropriate political approach in the face of this? We have to be both materialist and rational, but we have to shift these qualities onto the right grounds (2018: 65). For instance, how can we call rationalist a civilization that has created a world where parents are prevented from leaving an inhabitable world to their children? We need to turn away from the global and instead to the Terrestrial. The view from nowhere which has dominated much scientific and supposedly objective and rational thought cannot be sustained. This also means that the division between knowledge seen from afar but assured, and imagination as seeing things up close but without grounding in reality, also needs to be abandoned (2018: 69). We need to acknowledge as argued also by the new materialists such as Bryant and DeLanda, that agency is distributed and that it is the entangled engagements of the human and non-human assemblages or collectives that determine life in the Terrestrial, and this requires a broadening of both science and reason. What is required is a balancing act between an attachment which allows us to get away from the illusion of a Great Outside and a detachment which allows us to escape the illusion of borders (2018: 93). This can only be achieved by generating alternative descriptions. A dwelling place is that on which a terrestrial depends for its survival, while asking what other terrestrials also depend on it. That is where Latour ends though and as with all such attempts to redefine the very territory, one wonders whether this goes far enough. The attempt itself though is perhaps the most important contribution and does point towards new ways of thinking about and articulating the problems we now face.

Stiegler on Knowledge

I follow one concentrated section of Stiegler’s writing in order to present what is a recurrent theme in his work, in this case a short extract from Automatic Society, Volume 1: the Future of Work (2016). This subject has powerful resonances with theological approaches to this concern. Following on from his wider critique, it is clear that Stiegler is keen to point out the disadvantages created by digital technology. New forms of knowledge are created by what he calls the shock of encounters with contemporary developments. When these are the result of the automation and standardization resulting from the digital, however, he suggests that what emerges is stupidity rather than knowledge (2016: 12). A crucial difference is that between knowledge as information and knowledge as participation. Encounters through the digital which overwhelm us with both the speed, volume and diversity of material are in danger of reducing knowledge to information. We are bombarded with data which we do not often have the time or capacity to process and so are likely to absorb in an unreflective or uncritical fashion.

Stiegler proposes that ‘real knowledge’, by contrast, always comes ‘too late upon the scene’ (a reference to Hegel), as what must come first is ‘life-knowledge’ or ‘savoir-vivre’. This is knowledge of how to live and therefore gives us the context in which to locate what then comes to us as ‘savoir-faire’, which is more about how to do things, in this case as mediated by digital technology. Stiegler is concerned that the traditions, practices and general cultural environments that provide the essential background to our lives which are passed down through the generations are themselves being short-circuited by the immediate and instant access to ideas available through the Internet. What is presented is more likely to be the equivalent of sound bites or simplified memes easily reproduced through this new media rather than the full depth and subtlety of those traditions. One notes that this is a danger of presenting religious ideas via this medium and thus limiting access to our knowledge of the range of interpretations developed over time by different writers. Difference is reduced by this form of standardization.

The result of this is effectively a dead end or form of nihilism, according to Stiegler (2016: 15), and the negation of knowledge itself. The problem is that we are not even aware of this as we confuse information with knowledge. One could argue that information which is not internalized and made part of one’s own intellectual development remains superficial but also leaves us more easily open to manipulation. We believe that which confirms our pre-existing beliefs or which plays into our prejudices as we do not have the time to give deeper reflection to the constant stream of ‘news’ which is available to us. So, the worst impacts of digital technology are that it destroys what Stiegler calls desire, or the libidinal economy, and leads instead to a loss of care and attention. Is there any sort of alternative or antidote to this?

The theologian Paul Tillich talks about the knowledge of control as against the knowledge of reception and also highlights the idea of knowledge as participation (1978: 94–100). It is only when we are fully and practically engaged with a particular piece of work or project that we really enter into the depth of relationship which leads to the type of knowing that can change us rather than just offering a superficial encounter. This is certainly true of the religious life which demands so much more than simply a fleeting knowledge of external practices or ideas. Both time, effort, and regular discipline are involved. This perhaps is where religions with their concepts of sacrifice, vocation, the importance of the ‘slow work of time’ and the need to repeat through prayer and worship, come into their own. Liturgy and religious symbolism require that willingness to return, to attend fully, and to be open to the other that may provide an antidote to the instant but superficial responses to the digital. Practices of care, trust, connection and the capacity to envisage alternative futures each seem to be vital in order to combat the worst excesses of the influence of the Internet.

Earthing: Grounding and Rediscovering Our Bearings

What emerges very clearly from both Latour and Stiegler in their recent work is the need for what Latour calls earthing and Stiegler’s demand for a type of fully engaged knowledge which itself grounds us as we attempt to grapple with the instant and incessant demands of the digital. To describe this in graphic terms, we need to re-orient ourselves, to rediscover our bearings by establishing points of reference which help us to navigate through what is unfamiliar and dangerous territory, most of which is of our own making. We are ‘all at sea’ with both the environmental and the digital, but rather than ploughing on ahead at top speed, we need to slow down, take stock, assess our true location and take time to work out both where we are and where we think we ought to be. The problem is that we are forced to think, act and respond without taking that due time out. The questions therefore are how to analyse these dangerous waters so that we can see more clearly where we are—to get our bearings—and then to rediscover the resources we might have to hand which enable us to plot a course which steers us away from the rocks ahead and into calmer and safer waters. Both these tasks require a different experience of both time and space. From the perspective of religion, what resources are available to assist this process of both analysis and response? The next sections will address these issues.

For instance, Stiegler argues that the worst of impacts of digital technology destroy desire and the libidinal economy, thus leading to a loss of care, attention and presumably the negligence which both Latour and Stiegler are concerned about and for which they see religion as offering alternatives and an antidote. Otium as used in Theology and New Materialism (Reader 2017) concepts of sacrifice, vocation, the slow work of time, a different pace of engagement with those others to whom one should be connected both human and non-human. Once again, religion can be interpreted as assembling, linking, connecting, gathering and diplomacy (Latour). Is prayer and indeed liturgy plus religious symbolism related to knowing how rather than knowing that? So, the slow work of time always already exists as would be recognized by the apophatic tradition but also needs to play into the continued practices which are the relational aspect of relational Christian realism.

The possibility of a modest ethics of non-appropriation may seem an unrealisable ideal (but is perhaps still present?); then, is there a form of non-appropriating appropriation. Also, since Tillich talks about the unity between unity and division (my term) which again sounds like the tension between the apophatic and the relational, is there in fact a double disjunction rather than a single disjunctive synthesis between the two as I argued in Theology and New Materialism (Reader 2017)—so there is both that unity between unity and division and division between unity and division rather than some overarching completing synthesis of a metaphysical nature?

How then might religion restore faith in the future or provide resources to heal the epistemic breach? There has to be the recognition of both proximity and distance, a reciprocal and unresolved tension between the apophatic and the relational (as in relational Christian realism), recognizing the potential role of religion in trust, care, attention, connecting, fidelity, long circuits of time, intermittances, spaces of dissent, working with the pharmacological aspects of the technology to create positive alternatives at a collective and community level such.

Disinhibition

My objective is to identify concepts that span both the environmental and the digital in terms of analysis but also possible ways of addressing the challenges. Disinhibition is referred to by both Latour (2017: 191ff) and Stiegler (2019: 108–131) with both building on recent work by Fressoz (2012). A definition before we explore further:

The word disinhibition condenses two moments of the passage a l ‘acte: that of reflexivity and that of its being disregarded, that of taking danger into account and that of its normalization. Modernity was a process of reflexive disinhibition aiming to ‘legitimate the technological fait accompli’. (Fressoz 2012: 16 in Stiegler 2019: 126).

In other words, the account that is often presented of the environmental movement that only recently have we become more generally aware of the dangers we are creating for ourselves is inaccurate and misleading. We have known all along that there were risks and detrimental consequences of the path we have been following, and the evidence is there to prove this. The question then becomes that of how and why we have known this for so long and yet pressed ahead anyway.

The conclusion that forces itself on us, disturbing as it may be, is that our ancestors destroyed environments in full awareness of what they were doing…. The historical problem therefore, is not the emergence of an ‘environmental awareness’ but rather the reverse: to understand the schizophrenic nature of modernity, which continued to view humans as the products of their environment at the same time as it let them damage and destroy it. (Bonneuil and Fressoz 2017: 196–197).

A similar argument can be presented in terms of all technology but particularly the impacts of the digital. We are not unaware of the dangers and limitations which are being constantly researched and made public, but that despite all these, we go ahead anyway. Is this despite the risks, or even perhaps because of the risks? As a fan of Star Trek, the strap line of the series ‘to boldly go’ encapsulates a fundamental aspect of what it is to be human. Or does it? Is this an attitude and response peculiar to modernity and unrepresentative of previous eras of human history and development? In the business culture, we are accustomed to producing risk registers and scoring the various risks according to a supposedly objective hierarchy, and the taking appropriate action. The sad irony of this at the time of writing with a global pandemic in full swing is that this particular risk was either ignored or underestimated. Despite all of our best efforts—if such they were—we now face the most serious challenge to the global health and economy for many years. Did we know the risks, then ignore them and go ahead anyway? Or do our attempts to calculate and control represent nothing more than human hubris?

To address that question, it is worth exploring the respective explanations from Latour and Stiegler in a bit more depth as each reveals ideas of importance. Latour first of all. Echoing Fressoz’s point, he asks why it is that ecological questions do not appear to be of direct concern to our identity, security and property. The response that it is because of distance from the events or their implications does not bear scrutiny as it is not the case with other examples such as terrorism. ‘No, reactivity and sensitivity are what have to be considered. Collectively we choose what we are sensitive to, what we need to react to quickly’ (Latour 2017: 191). Indeed, in previous generations, people have been willing and able to respond to the sufferings of others who are distant, so it is as though we have decided to be insensitive to beings of a certain type, those who are connected to ‘the strange figure of matter’. Hence, the question is why we are not true materialists. That is obviously of interest when we bring in the ideas of NM and its claims that we do now in fact have access to a wider understanding of the dynamism and creativity of the non-human.

Where there is inhibition, Latour suggests, is largely when we begin to reckon with retrospective consequences—in other words, when it is often already too late and the damage has been done. Thus, the concerns about regulation and legislation. Where the future is concerned, however, disinhibition is the order of the day. We press ahead regardless. So, what is the source of this disjunction? Latour attributes this to what he calls ‘counter religion’ which requires us to go back in time before the tangle of science, religion and politics became inextricable. This assumes a contrast between traditional religions which are relatively indifferent to questions of falsity and truth, and those for which the issue of truth becomes essential (2017: 193). The issue at stake is one of certainty and being able to make claims that discredit or challenge potentially opposing traditions. To prevent people continuing to persecute and kill each other in the name of religious certainty, the claims have to be shifted elsewhere, for instance, to the realms of science, economics or even politics. This solution though ‘froze the battle lines but did not bring real peace’. Rather, it paralysed the Moderns, particularly in the way that they registered reactions to the materiality of their innovations. I am not entirely convinced by this, but what are of importance in Latour’s explanation are the religious dimensions that lie behind this.

Latour’s view is that what lies behind this is the resurgence of the term apocalypse. Environmental issues are often presented in this way, and we could be living in the shadow of an apocalypse even now. In the light of Covid-19, one can recognize such evaluations of the present. Counter religion supports the interpretation that we are already living in the ‘end times’. For instance, the view of some US Christian groups that Trump, despite his obvious personal failings, is somehow God’s instrument at work to bring about the end of the current order and the initiation of God’s rule on earth. In which case, ‘bring it on’, whatever the disaster might be! So, this is the end of time within time: ‘a certain number of peoples tell themselves henceforth that they are absolutely certain that they have reached the end of time, have arrived in another world, and are separated from the old times by an absolute break’ (2017: 195). In which case, they have already crossed over to the other side and it is pointless attempting to reason with them about caring differently for the here and now. Negligence is the order of the day from now on. Rather than living in the expectation of the apocalypse, we are living after its realization (Latour 2017:199). This is Latour’s explanation for climate scepticism and denial.

I would have a response to this from within the discussion about New Materialism and relational Christian realism as both question the traditional view that there is an identifiable and definite end point, telos or purpose in creation towards which Christians look and for which they hope. An established scientific viewpoint might be that no such telos can be identified as the future is radically open, unknown and probably unknowable. Either that or one might agree with the philosophical theologian Caputo (2019) that one should not sign up to a view that God will somehow intervene in the course of human or cosmic history to reconcile or restore relationships. In any case, as the scientists tell us, this whole world as we know it now will pass away in due course when our sun explodes and our solar system is destroyed, or even when the expansion of the universe goes into reverse and contracts into a single point. ‘Keep the future open, come what may, unconditionally, for better or worse, until death do we part’ (Caputo 2019: 276). No one will ride up on a white charger to put everything right or back in place. This is of course a deeply contested view within orthodox Christian circles, but one that has significant consequences for how we understand creation, the place of the human within it and what responsibilities humans have towards it including both the environmental and the digital. One does not have to take an extreme view on apocalypse to realize that if one believes in some future divine intervention or reconciliation, then this has consequences for one’s ethical response to creation in the here and now. What impact will these differing interpretations and understandings have upon our willingness or otherwise to limit or deliberately inhibit the constant striving for ‘progress at any cost’? This is the question with which Latour’s approach faces us.

While there is still time, let us turn to Stiegler. In the early sections of his chapter on the subject (2019: chap. 8), he works with ideas from Descartes, Foucault, Derrida and Sloterdijk to lay out the territory of the Anthropocene as described by Bonneuil and Fressoz, with his basic argument being that capitalism’s economy of disinhibition is based on calculation and latterly the deployment of algorithms (2019: 111). This leads to forms of what he calls madness, itself dependent upon hubris or the human capacity to exaggerate its powers of control and thus underestimate the dangers faced by relentlessly pursuing technological innovation. If risks can be predicted, evaluated, calculated and then taken into account when it comes to decisions about future developments, then they can be attributed a mathematical value which appears to make them containable and acceptable. To the extent that we believe this to be the case, we are certainly indulging in a form of madness and indeed self-deception. Globalization extends this and creates further levels of disruption: ‘The disruption now underway, as a new stage of the organization of disinhibition and an extremization of these tendencies characteristic of the Anthropocene, is at the same time being extended to the entire planet, via digital networks functioning at two thirds light speed’ (2019: 124). This leads to the breakdown of territorial immunities, which itself prepares the way for counter reactions, presumably such as revived nationalism.

The main concern though is the impact of this upon the willingness to take risks regardless of the consequences, or in the misguided belief that any risks can be measured and catered for in advance. In effect, a new morality comes into existence as a result, one example of which rather unfortunately given the current crisis is that of inoculation, which itself leads towards the idea that the human body can be transformed and indeed improved. ‘This morality consisted of a practice both of puritan prohibition and the destruction of public power so as to deregulate not only the circulation of commodities but also industrial science, and as such it resembled an early elaboration of the transhumanist discourse of the libertarians’ (2019: 129–130). The insurance industry would be another example of the reliance upon the capacity to calculate and predict and thus set financially acceptable levels of contribution and reward. In other words, we encounter concerns with issues of trust, calculability and speed and how these are central to the developments of digital technology and how decisions about future directions will be evaluated. The short-circuiting of the human critical thought processes which ought to guide and accompany such decisions is a likely consequence of the disinhibitions which themselves lead to a misplaced trust in our capacity to control and limit the powers of the digital, let alone the global companies that now determine so much in this field. Underlying this are deeper questions about what it is to be human and how the human and non-human interact and are entangled with each other, thus a link back to the New Materialism and relational Christian realism themes of distributed agency. How do we keep ourselves in check when the technologies we have created spur us on to ever more rapid or instant responses and tempt us to bypass the need to take more time for reflection and consideration?

Hence, the contributions of Latour and Stiegler in their different ways illustrate that the concept of disinhibition spans the concerns for environment and digital technology and aids analysis of the problems that need to be addressed.

Autoimmunity

Autoimmunity, like disinhibition, provides another helpful way of analysing the dangers and challenges of the environmental and the digital. The term originating from a medical context is deployed by Derrida, particularly in relation to the events of 9/11 but also with reference to religion and technology. He defines this as follows: ‘An autoimmunitary process is that strange behaviour where a living being, in quasi-suicidal fashion, ‘itself’ works to destroy its own protection, to immunize itself against its ‘own’ immunity’ (Derrida in Borradori 2003: 94.) In some ways, this aspect of human behaviour is as difficult to understand as disinhibition. Why destroy the very systems that protect oneself from harm? This does occur biologically of course as we know with the current Covid-19 pandemic where the virus triggers the immune system to overreact and begin to attack its own life support systems, at least in its most extreme and dangerous forms. Derrida, however, is talking about how humans respond knowingly and deliberately, or perhaps on occasion through self-deception and misunderstanding. Our particular concerns are the climate crisis and then digital technology but it is worth first of all examining how Derrida uses the concept.

With reference to the events of 9/11, Derrida points out (Borradori 2003: 91) that the high jackers employed high-tech knowledge to take over American planes, in American cities, to fly them into American targets. The high jackers themselves trained and prepared for this action in the USA, and, of course, the USA had previously had a hand in training and equipping Bin Laden. So, this was an enemy within, whose very existence was at least partly the result of American foreign policy. The system works against itself to bring about a degree of internal destruction. One might ask oneself about the equivalents when it comes to climate change. Dependence upon fossil fuels and the power of the oil industry come immediately to mind. Foreign travel which has been brought to a halt by the Covid-19 crisis and which creates vast amounts of pollution, and indeed internal travel, the absence of which has resulted in a great improvement of air quality in our major cities, is further example. Indeed, there is some evidence that more widespread intense farming methods have led to poorer farmers being forced to the margins in China and this is what has resulted in the virus becoming more easily transmitted to humans. We continue to endanger ourselves through our own actions and our impact upon the planet we inhabit.

Derrida’s second argument in relation to 9/11 is to do with the nature of trauma and how this relates to our understanding of time. ‘A weapon wounds and leaves forever open an unconscious scar; but this weapon is terrifying because it comes from the to-come, from the future, a future so radically to come that it resists even the grammar of the future interior’ (Derrida in Borradori 2003: 97). The impact of the attacks was to open up in our minds the threat of further devastating attacks of a different nature, biological or even an attack on a nuclear establishment. So, it was not just the event in itself but what it represented and offered in terms of future possibilities. How were we to live with this? Once again, there is perhaps a parallel with the threat of environmental disaster. We live with accounts of sea level rises and the knowledge that a considerable proportion of the world’s population live along our coastlines, let alone that low-lying islands are already starting to be overwhelmed. Yet, we do nothing, or very little. I have heard one scientist say that until New York is flooded, by which time it will already be too late, we collectively will not be prepared to change our way of life sufficiently to counter such disasters. So, the trauma haunts us like an unwelcome shadow but still we persist in pursuing the behaviours and policies that bring us ever closer to our own destruction. How can this be explained? Latour of course has suggested an explanation as we have already seen. The end has already happened and this is simply just a matter of living it out.

A third strand of Derrida’s argument is that attempting to combat or resist the threat involved often has the perverse effect of creating or escalating the problem. So, responses to 9/11 in terms of the ‘war on terror’ actually fed the hostility and became a rallying point for those who would want to continue the attacks in another form. ‘For we know that repression in both its psychoanalytical sense and its political sense—whether it be through the police, the military, or the economy—ends up producing, reproducing, and regenerating the very thing it seeks to disarm’ (Derrida in Borradori 2003: 99). This is perhaps less immediately relevant in the case of climate change or digital technology, except to say that every action creates a counter reaction, and climate deniers are the shadow side of climate change campaigners where the more vehement and vigorous the attempts to change patterns of behaviour the more strident the voices which contradict and challenge. Once again, we appear to destroy the systems that might protect us from the inside.

In another publication, Derrida and Vattimo (1998) employ the concept to specifically address the relationship between religion and what he refers to as techno-science. Arguing that one of the characteristics of religions is that they point towards the infinite, that which is of ultimate value and should remain safe, sacred, holy and set apart, when it becomes articulated through the automated mechanisms of technology, run the risk of undermining their own beliefs and practices (1998: 50–51). What should be immune and above all human techniques of reproduction is re-presented both within and beyond faith communities by the very technical means it stands to critique. This is a general problem of course, that of how to express that which is beyond expression or comprehension, but is exacerbated by the global reach of digital technology which can both reduce the depth of understanding and also speed up its circulation to a point where responses are automated and superficial. There are clear links here to Stiegler’s work (2013: 64) where he talks about the short-circuiting by algorithmic means which destroys the fidelity and trust which are characteristic of a faith commitment. That which should be protected and immune from the limitations of the technology becomes subject to its functioning and in danger of being reduced to sound bites or snippets rather than being true or faithful to its deeper traditions and practices. So, we can see that the concept of autoimmunity ranges across both the environmental and the digital domains and raises again the question of whether any alternatives are to be developed.

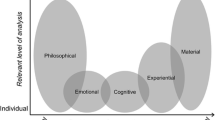

Modest Ethics

We need to move beyond analysis to possible alternative approaches to the issues surrounding both environment and digital ethics, and one of the proposals that has emerged from the Trinity groupFootnote 2 (Reader and Evans 2019) is that of a modest ethics, linked to a similar modesty in both science and religion, but one has to be careful with this terminology. A modest claim is still a claim which itself suggests a degree of force in the argument. Behind this lie a series of substantive positions as articulated in the work on New Materialism and relational Christian realism: knowledge as embedded and material rather than distant and abstract taking into account non-specialist perspectives, material practices and the insights of other disciplines. Plus a willingness to acknowledge the other levels at which humans function, those of feelings and instincts as well as what is normally termed the logical and autonomous, and then the realization that one is always already in relationship with the non-human in shifting and evolving assemblages. Rather than lone individuals exercising a means-ends rationality, we perceive that we operate within a distributed agency and that can mean that we are as much shaped by the technology we devise as we imagine the creation is under our complete control. Along with some of the other influences identified such as the work of Latour and Stiegler, this can lead to a more modest ethics drawing on the insights of New Materialism as related to the themes just identified. Ethics is less about constructing frameworks according to which one can judge whether or not one is living a good life or taking appropriate actions than being worthy of the events over which one has no or little control. Can I and we affirm, enhance and intensify such events through the capacity to affect and be affected? In order to be of some practical use, however, this requires a capacity to reflect and act and not simply to be swept along by events.

For example, the UK is at the beginning of rolling out 5G, the next generation of smart technology which will apparently link machines to machines as well as machines to humans. Fridges will be able to know when stocks are depleted and re-order without human intervention. Cities will have so many monitors that cars will be able to know traffic conditions beyond human sight and adjust accordingly. This may be less effective out in rural areas, but for city living, a new era of interconnectedness and machine-directed interactions will become the norm. This is presented as simply the next stage in the development of current technologies and enhancing the capacity to speed up responses and activity. Beyond the obvious concerns about national security because of the Chinese company being employed to construct these systems, there are much deeper questions about the values and decisions that are already built into this process. We already know that companies such as Google and Facebook use the technology to track our movements and habits which are then made available to advertisers in order to be able to target us individually—we become the product rather than us consuming other products. How will 5G then add to the powers of these companies to predict, shape and influence our behaviour? Privacy has been sacrificed for the sake of convenience and speed of response. Exactly which values and biases have already been built into the technology and of which we will have little or no knowledge or understanding? Algorithms beyond our ken will determine what we will be told and what will remain hidden.

The concern with a traditional rights based or even environmental ethical approach is that both come too late on the scene. They apply certain ethical principles only after the important decisions have already been made: the targeting and the biases are already built into the systems being deployed. Trying to identify or even challenge and change those once they are already functioning is going to be too late. Governance procedures might limit the scope of these operations, but no more than that. The difficulty is that of entering the debate at an earlier stage before the decisions have been made. We would argue that the understandings of a modest ethics as above stand a better chance of avoiding the instrumentalist approach of more traditional ethical frameworks—in other words, the ethics is no more than an application of ideas to systems that are already in place—and instead engage with the material energies and movements embedded in the technologies as they are being developed. This becomes a political as well as an ethical challenge.

One final but vital contribution that can be offered by a modest religion in addition to the concerns about well-being. In a recent book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism Zuboff proposes that the ancient idea of sanctuary might be of value (2019: 478). In other words, previous societies understood that there had to be safe spaces free from external influences in order for humans to continue to operate with a degree of freedom and sanity. In Theology and New Materialism, I suggested that the philosophical concept of chora/khora might function in a similar fashion (Reader 2017: 36–7). This is the space/place of no space/place beyond external human control where one might encounter a different reality. Without going into further detail, I present this as an essential antidote to the potentially all-consuming and full-spectrum dominance of the commercially driven technology companies now shaping our societies in their own image. A modest but substantial contribution to the ongoing ethical debate. Where are such sanctuaries to be discovered and how are they to be protected?

Proximity and Distance

Another area where relational Christian realism presents an alternative approach is what I refer to as the dynamic or tension between proximity and distance. What we experience with digital technology is generally a lack of space and distance as everything is instant and immediate and we are tempted to respond unthinkingly and without due care and attention. Religious traditions still protect that delicate and vital dynamic which allow for withdrawal, and the capacity to distance oneself from the immediate. (The ‘right to be forgotten’ is an interesting position in this respect). I use the terms relational and apophatic to describe this in the book. Latour and New Materialism are strong when it comes to describing the relational, and this is crucial, but less convincing when it comes to acknowledging that which escapes description and articulation (the apophatic). This again is where religious traditions still have an advantage in that they can point to that which lies beyond, even though these might be mini or local transcendences. Spaces for other spaces or what is called khora from this tradition are another means of articulating this priority.

A further dimension is perhaps an ethics of non-appropriation or allowing others (human and non-human) to exist for themselves in their own right rather than as what they might be for us. Whether and to what extent this is really possible is a subject for further exploration, but it is certainly part of the picture for a relational Christian realism ethics. There is much more to be developed and examined in this field, but the contributions of New Materialism as supplemented by the ideas from relational Christian realism form an appropriate contemporary approach to forming ethical responses to the subjects engaged in this paper. A final comment refers us back to the work of Derrida where he talks about ‘being eaten’ as meaning being appropriated by others for their own reasons, and where he suggests that this is an ideal which is often impossible to achieve, in which case the task is to ensure that one is ‘eaten well’. As we have little choice but to engage with the infosphere and digital technologies, the challenge is to work out what being eaten well means in practice as we reassemble each instance in Latourian fashion, but also seek to identify and protect those spaces (otium) which Stiegler identifies (2015: 89) as present in religious practices as well as elsewhere.

Panentheism

I am taking a standard definition of panentheism as follows: God is not essentially independent or separate from the cosmos, but God is affected by the cosmos while still being more than the cosmos. How does this relate to New Materialism and to our concerns for environment and digital technology? While acknowledging that theology is not a concern for New Materialism as such and that its various exponents would not want to identify with the following discussion, it becomes clear that there are at least some resonances worth exploring. The theologian who I would argue pursues these ideas in a promising direction is Catherine Keller (2015). The central ideas of New Materialism portray matter (both human and non-human) as vital, full of energy, in process and movement at all levels and in all combinations, opening up the possibility of being and becoming otherwise, a bit like a constantly shifting kaleidoscope. As humans, our perceptions rely on the capacity to either slow the movement down or hold it still for a few moments in order to capture or describe what it is we think we can see. The danger is that we identify each frozen image as the whole, or possibly a reliable glimpse into that whole, whereas the reality is that the picture has already moved on and will continue to do so. Even our ideas of God, if we hold such, are limited in this way, and we run the risk of limiting the full depth or scope of the divine by (as Latour would say) stopping the references circulating. Another shift of the kaleidoscope and the image changes once again. Where is God to be found in this? Is God the process itself, or our means of access to the process?

Panentheism: Proximity and Distance

A key question as already identified is how to maintain a dynamic tension between proximity and distance. On the one hand, a God who is so distant from the cosmos as to function merely as an external manipulator of both human and non-human affairs, or, on the other, a God who is so entangled and implicated in the cosmos at all levels that there is not that degree of distance or separation that a true panentheism requires. Even Keller (2015) in her interpretations of Whitehead and Deleuze struggles with this and realizes that there needs to be an additional element to the equation to hold this in balance. In my own work, I draw upon Keller to talk about this in terms of the tension between the apophatic and the relational (Reader 2017: 32ff). New Materialism and its counterparts in contemporary philosophy such as Whitehead and Deleuze are strong when it comes to the relational aspect but leave little scope for the apophatic, that which is often identified in the Christian tradition as the mystical or the unknown.

To return to Keller for a moment: the limitations of an approach which is overly dependent on a Deleuzean immanence becomes clear. ‘God signifies the particular relation of particular creatures to the infinity of the world. All, pan, can be said to be “in God” because all is enfolded, complicated, in and as God, in the consequent nature—and unfolded, as God is in all, in and as the creaturely decisions.’ (Keller 2015: 190–191) This still requires though understanding creativity as a bottomless flux or infinite abyss, a grounding which is something more than simply this relation or process. This would be the apophatic which lies beyond, or above, or elsewhere from the proximity and entanglements of mere process. The problem with Deleuze is that ‘the en of panentheism remains a relation, a fold: it marks the difference precisely as the nonseparability of pan and theos. The en is, of course, the prefix of immanence’ (Keller 2015: 191). This remains smudged as Keller says and internal to the relata it relates. In other words, one has not convincingly escaped the proximity which fails to take into account the distance which could be provided by the apophatic.

Keller goes on to talk about amorous entanglements and the power of God’s implicated love, both of which one can acknowledge as being recognizable elements from the Christian tradition. Holding the tension and maintaining enough distance to still be able to argue that God is engaged in the world yet not to be fully identified with it is not possible without some further element of difference. While Deleuze and New Materialism theorists might be able to retain this in theory, they struggle to describe this in anything other than abstract philosophical terminology and this is a limitation of their approach when it comes to more theological requirements.

There are other philosophical sources that provide a more convincing means of holding the dynamic tension between proximity and distance, between immanence and transcendence. Latour is certainly one of those with his concept of local or mini transcendences (see for instance Miller 2013: 38–39 and Reader 2017). The importance of this for discussions of the environmental and how to retain an appropriate relationship between the human and the non-human emerges from that material. I would argue that New Materialism is of more direct theological relevance when it comes to the issue of agency, and particularly the concept of distributed agency which makes it clear that there are limits to the value of the idea of human autonomy. A further area where there may well be tension between New Materialism and theology is that of whether or not there is a determinate purpose or telos in creation, something that New Materialism thinkers would want to remain open at best. If God is as a panentheistic understanding would imply, then one might want to argue that there is indeed such a determinate purpose even though it cannot be fully known.

Conclusion

In the conclusion to his book on living together in a world transformed by technology, Jamie Susskind (2020: 348) asks whether we are devising systems of power that are beyond the capacity of flawed and damaged human beings to control or manage. He believes that this is the case and the task which lies ahead is to ‘get working on the “wise restraints” that could mitigate the oppressive consequences’. The question which emerges from my work on New Materialism, and then that of Latour and Stiegler, is whether or not this is a realistic scenario. What Susskind is proposing takes us into the realms of governance and regulation as the most hopeful way forward. Yet, as I have argued elsewhere (Reader and Savin-Baden 2020), even this may be too late as the values which determine the algorithms which will shape our lives have already been selected and implemented at the behest of the big tech firms and those whose interests they serve. The postdigital age is already here (Jandrić et al. 2018) and, in some cases, the damage has already been done.

In terms of the environment, the same picture emerges. It may already be too late. The concepts of disinhibition and autoimmunity may simply be the latest version of an understanding of human nature that goes back much further. Weakness of will is one interpretation of Aristotle’s term akrasia (2009: 1152), and St. Paul in his Epistle to the Romans (7.19) says ‘for I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do.’ Is this something fundamentally flawed in human nature which goes even further than this propensity to take ‘calculated risks’ and to press ahead with innovation and unpredictable developments whatever the cost which is the concern of Stiegler and Derrida? Latour goes deeper than this when he argues that we now live on two different planets, with a global elite no longer sharing the same earth or the same practices. I am not so sure this is about apocalyptic in the way that he suggests though, but more about the belief of this group that they have means to protect themselves from the worst impacts of what lies ahead. What is it that prevents the ship being turned around before we hit the rocks? The vested interests of the fossil fuel industry obviously, but also those who make their money by gambling on the stock markets and can cash in on any disaster. The current Covid-19 crisis reveals the reality of this divided planet. It is clear that certain sections of the population are expendable. Those who are already suffering a significant proportion of infections and deaths in the UK are from the black and minority ethnic communities, and it is clear that the capacity of 3rd world populations to resist the virus is more limited than the US and Europe despite the failings of many of their governments. The proportion of those of us who are expendable is growing as global inequalities expand, while the elite can always relocate and shelter from the storms ahead—or so they believe.

Can a modest ethics which tones down the claims of science and religion and might hold the politicians and their paymasters in check make a difference? Can a different concept of the divine which holds in tension proximity and distance, the relational and the apophatic, be an effective antidote to the impacts of environmental damage and technological determination by the big companies? Are we heading for a further expansion of the inequalities which were exacerbated by the Global Financial Crisis as a result of Covid-19? Does the philosophy (and ethics) always come too late upon the scene? The most optimistic scenario is that it is too early to tell and that the growing proportion of those of us ‘left behind’ will take the time that is left to strive for an alternative social and political order that can do more than simply mitigate and adapt. One can see how the story of a benevolent external intervention (only a god can save us now) has its attractions, but this may be down to us in the time that is left to rediscover our bearings, identify the crucial points of reference and act to steer the ship away from the rocks which loom ahead. If this requires a ‘profound interior conversion’ as the Pope has suggested (2015: para 217), then it needs to get underway immediately and a new course plotted sooner rather than later.

Notes

See William Temple Foundation, https://williamtemplefoundation.org.uk/about-the-foundation/. Accessed 16 April 2020.

See https://williamtemplefoundation.org.uk/our-work/ethical-futures-digital-and-ecological/. Accessed 21 April 2020.

References

Aristotle. (2009). Nicomachean ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Badiou, A. (2003). St Paul: The Foundation of Universalism. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Baker, C., James, T., & Reader, J. (2015). A philosophy of Christian materialism: Entangled fidelities and the common good. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Bonhoeffer, D. (1976). Letters and papers from prison. London: SCM Press.

Bonneuil, C., & Fressoz, J.-B. (2017). The shock of the Anthropocene. London: Verso.

Borradori, G. (2003). Philosophy in a time of terror: Dialogues with Jurgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Braidotti, R. (2013). The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bryant, L. R. (2014). Onto-cartography: An ontology of machines and media. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Caputo, J. (2013). The insistence of god: A theology of perhaps. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Caputo, J. D. (2019). Cross and Cosmos: A Theology of Difficult Glory. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Crockett, C., & Reader, J. (2016). Ecology and social movements: New materialism and relational Christian realism. In J. Rieger & E. Waggoner (Eds.), Religious experience and new materialism: Movement matters. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

DeLanda, M. (2011). A new philosophy of society: Assemblage theory and social complexity. London: Continuum.

Derrida, J., & Vattimo, G. (1998). Religion. Cambridge: Polity.

Fressoz, J.-B. (2012). L'Apocalypse joyeuse: Une Histoire du risque technologique. Paris: Sieul.

Harman, G. (2010). Towards speculative realism. Essays and lectures. Ropley, Hants: Zero Books and John Hunt Publishing.

Hui, Y. (2016). On the existence of digital objects. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Jandrić, P., Knox, J., Besley, T., Ryberg, T., Suoranta, J., & Hayes, S. (2018). Postdigital science and education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 50(10), 893–899. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2018.1454000.

Kearney, R., & Zimmerman, J. (2016). Reimagining the Sacred: Richard Kearney Debates God. New York: Columbia University press.

Keller, C. (2015). Clouds of the impossible: Negative theology and planetary entanglement. New York: Columbia University Press.

Latour, B. (2004). Politics of nature: How to bring the sciences into democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Latour, B. (2007). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Latour, B. (2017). Facing Gaia: Eight lectures on the new climatic regime. Cambridge: Polity.

Latour, B. (2018). Down to earth: Politics in the new climatic regime. Cambridge: Polity.

Miller, A. S. (2013). Speculative grace: Bruno Latour and object-oriented theology. New York: Fordham University Press.

Pope Francis. (2015). Laudato Si: The search for a common home. Rome: Catholic Press.

Reader, J. (2017). Theology and new materialism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Reader, J., & Evans, A. (2019). Ethics after new materialism: A modest undertaking. Chester, UK: William Temple Foundation.

Reader, J., & Savin-Baden, M. (2020). Ethical conundrums and virtual humans. Postdigital Science and Education, 2(1), 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-019-00095-2.

Stiegler, B. (2013). What makes life worth living: On pharmacology. Cambridge: Polity.

Stiegler, B. (2015a). States of shock: Stupidity and knowledge in the 21st century. Cambridge: Polity.

Stiegler, B. (2015b). Symbolic misery. Volume 2. Cambridge: Polity.

Stiegler, B. (2016). Automatic society. Volume 1: The future of work. Cambridge: Polity.

Stiegler, B. (2019). The age of disruption: Technology and madness in computational capitalism. Cambridge: Polity.

Susskind, J. (2020). Future politics: Living together in a world transformed by tech. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tillich, P. (1978). Systematic theology. Part 1: Reason, revelation. Part 2. Being and god. London: SCM Press.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. London: Profile Books.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reader, J. From New Materialism to the Postdigital: Religious Responses to Environment and Technology. Postdigit Sci Educ 3, 546–565 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00154-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00154-z