Abstract

One provision of the Affordable Care Act was Medicaid expansion, which increased eligibility in two ways: it raised the income threshold from 100 to 138% of the poverty line, and removed categorical restrictions, such as being a pregnant woman, to include all low-income adults. We capitalize on this policy change to determine if eligible Hispanics and Spanish speakers are more or less likely than their non-Hispanic and English-speaking counterparts to enroll in Medicaid. We use National Health Interview Survey data and apply a theoretical framework of social capital acquisition. We find that Hispanic Spanish speakers and Hispanic English speakers are about twice as likely to have Medicaid after the ACA expansion. However, Spanish speakers are about 75% as likely to have enrolled in Medicaid than their English-speaking counterparts post-ACA. In the NHIS sample, about 28% of Hispanic Spanish speakers have Medicaid. We see considerable evidence that Hispanics who have more social capital are much more likely to enroll in Medicaid. Even though the ACA expansion reduced the uninsured gap for Hispanics, there is still a noteworthy disparity in rates of insurance coverage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 1996, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act restricted Medicaid coverage to citizens and long-term permanent residents who have lived in the USA for at least 5 years, however there are exceptions for refugees, veterans, asylum-seeker, and victims of domestic violence and sex trafficking. (NCSL 2018). Although Medicaid is a state-run program, states have autonomy in the provision of benefits to immigrants.

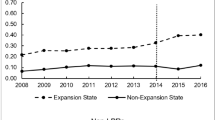

We also include the results of linear probability model and a plot of the predicted values of the LPM in Appendix 2. Looking at the plot, we see a bit over 10% of the predicted values fall below 0. As such, the LPM makes predictions that are non-sensible for a significant number of observations. Thus, the logit model in Eq. 1 provides a more reasonable specification to determine marginal effects.

For a complete discussion, see Ai and Norton’s 2003 Economics Letters article.

References

Ai C, Norton EC. Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Econ Lett. 2003;80(1):123–9.

Antonisse L, Garfield R, Rudowitz R, Artiga S. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: Updated findings from a literature review. 2017

Bertrand M, Luttmer EFP, Mullainathan S. Network effects and welfare cultures. Q J Econ. 2000;115(3):1019–55.

Buchmueller TC, Levinson ZM, Levy HG, Wolfe BL. Effect of the Affordable Care Act on racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(8):1416–21.

Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol. 1988;94:S95–121.

Collins SR, et al. Who are the remaining uninsured and why haven’t they signed up for coverage? Issue brief (Commonwealth Fund). 2016;24:1–20.

Courtemanche C, et al. Early impacts of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage in Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36(1):178–210 Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w22182.

Daubón R, Carrasquillo A. Capital Social. San Juan: Editorial Tal Cual [Printed]; 2002.

Donfouet HPP, Mahieu P. Community-based health insurance and social capital: a review. Heal Econ Rev. 2012;2(1):1–5.

Doty MM, Blumenthal D, Collins SR. The Affordable Care Act and health insurance for Latinos. JAMA: J Am Med Assoc. 2014;312(17):1735–6.

Engbers TA, Thompson MF, Slaper TF. Theory and measurement in social capital research. Soc Indic Res. 2017;132(2):537.

Gee ER, Giuntella GO. Medicaid and ethnic networks. BE J Econ Anal Policy. 2011;11(1):1.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. 2018. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act. Accessed 13 June 2019

Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Kim D. Social capital and health. Chapter 1: Social Capital and Health. New York; London: Springer; 2008.

Migration Policy Institute. Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. 2018. Retrieved from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states#HealthInsurance. Accessed 13 June 2019

Mladovsky P, Soors W, Ndiaye P, Ndiaye A, Criel B. Can social capital help explain enrolment (or lack thereof) in community-based health insurance? Results of an exploratory mixed methods study from Senegal. Soc Sci Med. 2014;101:18–27.

Monnat SM. The new destination disadvantage: disparities in Hispanic health insurance coverage rates in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan new and established destinations. Rural Sociol. 2017;82(1):3–43.

NCSL 2018 http://www.ncsl.org/documents/health/MedicaidNetTK13.pdf. Accsessed 13 June 2019

Portes A. Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu Rev Sociol. 1998;24(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1.

Putnam RD. The prosperous community: social capital and public life. Am Prospect. 1993;13:35–42.

Rutledge MS, McLaughlin CG. Hispanics and health insurance coverage: the rising disparity. Med Care. 2008;46(10):1086–92.

Schembri S, Ghaddar S. The Affordable Care Act, the Medicaid coverage gap, and Hispanic consumers: a phenomenology of Obamacare. J Consum Aff. 2018;52(1):138–65.

Simon K, Soni A, Cawley J. The impact of health insurance on preventive care and health behaviors: evidence from the first two years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36(2):390–417.

Sommers BD, Maylone B, Nguyen KH, Blendon RJ, Epstein AM. The impact of state policies on ACA applications and enrollment among low income adults in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Texas. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2015;34(6):1010–8.

van der Goes DN, Santos R. Determinants of private health insurance coverage among Mexican American men 2010–2013. J Med Econ. 2018;21(11):1139–43.

Wehby GL, Lyu W. The impact of the ACA Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage through 2015 and coverage disparities by age, race/ethnicity, and gender. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):1248–71.

Yue D, Rasmussen PW, Ponce NA. Racial/ethnic differential effects of Medicaid expansion on health care access. Health Serv Res. 53;5(2018):3640–3656.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge help and guidance from Peter VanderHart, James Bland, participants of the Midwest Economic Association meeting, and three anonymous referees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

We calculate odds ratios in our results section in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. However, since in Eq. 3, we have both interaction terms and non-interacted terms of interest, one cannot simply look at exponentiated coefficients on a single variable to determine the correct odds ratios

For each of the below calculations, we calculate the ratio of the probabilities of the two groups having Medicaid. For example, in Table 2, we calculate the probability of a Hispanic person pre-ACA having Medicaid, the probability of a Hispanic person post-ACA having Medicaid, and take the ratio of those two probabilities. The result is an odds ratio.

Table 2: Odds ratios of Hispanic English speaker having Medicaid pre- and post-ACA

Table 3: Odds ratios of Hispanic Spanish speakers having Medicaid pre- and post-ACA

Table 4: Odds ratios pre-ACA of a Hispanic English speaker to a non-Hispanic English speaker having Medicaid

Table 5: Odds ratios post-ACA of a Hispanic English speaker to a non-Hispanic English speaker having Medicaid

Table 6: Odds ratios pre-ACA of a Hispanic Spanish speaker to a non-Hispanic English speaker having Medicaid

Table 7: Odds ratios post-ACA of a Hispanic Spanish speaker to a non-Hispanic English speaker having Medicaid

Table 8: Odds ratios pre-ACA of a Hispanic Spanish speaker to a Hispanic English speaker having Medicaid

Table 9: Odds ratios post-ACA of a Hispanic Spanish speaker to a Hispanic English speaker having Medicaid

For the enhanced measure of social capital involving neighborhood characteristics, responding that you agree, you trust (count on/are close with/help) your neighbors is coded as N (neighbor) = 1. In Eq. (4), we interact with the neighborhood dummy variables to determine if there is a differential effect of an increased social network on Medicaid uptake. Because of the numerous interaction terms, we again look at odds ratios.

Tables 10, 11, 12, and 13 each show the response to one of the neighborhood questions for 4 different groups. In each table, column (1) is the odds ratios post-ACA of a Hispanic Spanish speaker who trusts (counts on/is close with/helps) their neighbor to a Hispanic Spanish speaker who does not trust their neighbor having Medicaid

Column (2) odds ratios post-ACA of a Hispanic Spanish speaker who trusts (counts on/is close with/helps) their neighbor to a non-Hispanic English speaker who trusts their neighbor having Medicaid

Column (3) odds ratios post-ACA of a Hispanic Spanish speaker who trusts (counts on/is close with/helps) their neighbor to a non-Hispanic Spanish speaker who does trust their neighbor having Medicaid

Column (4) odds ratios post-ACA of a Hispanic Spanish speaker who trusts (counts on/is close with/helps) their neighbor to a Hispanic English speaker who does trust their neighbor having Medicaid

Tables 11, 12, 14 and 13 have the same 4 columns for each of the subsequent neighborhood characteristic questions.

Linear Probability Model

Summary Statistics for English and Spanish Hispanics

Changes in Medicaid Enrollment by Region

What we observe in Table 16 is that there were substantial differences in Medicaid uptake by region. In the West, for example, the number of people in the sample on Medicaid increased dramatically, from 5078 to 8022. While the data does not have a more granular geographic identifier than region, California comprises a significant portion of the Western region. Similarly, there was limited expansion in the South, from 6814 to 7990 individuals covered by Medicaid. As Texas makes up a significant portion of the South region, it is reasonable to think the low increases were due to Texas not expanding income eligibility.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abboud, A., Cook, A.C. Differential Rates of Medicaid Uptake for Hispanic English Speakers and Hispanic Spanish Speakers under the Affordable Care Act. J Econ Race Policy 3, 159–174 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-019-00036-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-019-00036-y