Abstract

The study applies a Random Utility model in examining household welfare from participating in Medicaid −a vital resource in millions of lower income working-age households across the US. Binary logits are estimated using pooled data (2013–2018) from the Current Population Survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) covering expansion and non-expansion state populations. The gains in Consumer’s surplus are highest for study units reporting ‘deep poverty,’ poor health status and being outside the labor force.

“The art of dealing with any problem at the theoretical, empirical, or applied economic level is to oversimplify in an artful and useful way versus oversimplifying in a dumb, crazy way…”.

– Arnold Harberger.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

New Mexico’s Medicaid program is referred to as Centennial Care, administered by the Medical Assistance Division of the Human Services Department.

- 2.

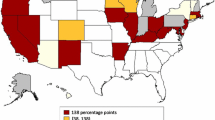

At the time of writing New Mexico is one of 31 expansion states. The timeline and status of State Medicaid Expansion decisions is available in “Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision,” State Health Facts, Kaiser Family Foundation (2019).

- 3.

The focus of the present study is on Medicaid/CHIP eligibility of non-disabled working-age and children populations under the ACA. For current status see, “Where are States Today? Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility Levels for Children, Pregnant Women, and Adults.” Kaiser Family Foundation (2019).

- 4.

Imputed values of in-kind benefits are time-specific and reflect household needs. Here, the costs of a vanilla market-based Silver Plan reflect average individual medical needs in 2014. These costs are noted to provide a sense of parity relative to Medicaid per capita costs.

- 5.

The study assumes a sample of Medicaid-covered individuals lose coverage and either become uninsured or take-up private coverage. The sample population is then randomly matched to a non-Medicaid population (uninsured or private-insured) to infer cost-savings from Medicaid

- 6.

The GAO study draws data from the National Health Institute Survey (NHIS), compiled by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

- 7.

Following Bound (1991) studies of endogenous labor supply tend to be sensitive to the measures of health used; in particular self-reported health status. This seems less complicating in the present study, which treats both variates exogenously, as well as education. Bound (1991, 2000) provides helpful discussions of measurement errors associated with subjective- and objective-measured health variables.

- 8.

The CPS ASEC study data were drawn from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, University of Minnesota Population Center. See Sarah Flood, Miriam King, Renae Rodgers Steven Ruggles and J. Robert Warren. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 6.0. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS 2018. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V6.0

- 9.

The broad SPM definition of household resources: cash income plus in-kind benefits (SNAP and housing assistance), minus tax liabilities, work/child expenses, child support payments, and medical out-of-pocket costs.

References

Baicker, K., et al. (2013). The Oregon experiment – Effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. The New England Journal of Medicine, 368(18), 1713–1722.

Blavin, F., Karpman, M., Kenney, G. M., & Sommers, B. D. (2018). Medicaid versus marketplace coverage for near-poor adults: Effects on out-of-pocket spending and coverage. Health Affairs, 37(2), 299–307.

Bound. (1991). Self-reported versus objective measures of health in retirement models. The Journal of Human Resources, 26(1), 106–138.

Bound. (2000). Measurement error in survey data. Report 00–450, Population Studies Center, University of Michigan.

Burtless, G., & Siegel, S. (2001). Medical spending, health insurance, and measurement of American poverty. The Brookings Institutiton, Washington, D.C.

Caswell, K. L., & Short, K. S. (2011). Medical out-of-pocket spending among the uninsured: Differential spending & the supplemental poverty measure (Working paper 2011–24). U.S. Census Bureau, Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division.

Citro, C. F., & Michaels, R. T. (Eds.). (1995). Measuring poverty: A new approach. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

Dalakar, J. (2017). The supplemental poverty measure: Its core concepts, development and use. Congressional Research Service, Washington D.C.

Foster, A. C., & Rojas A. (2018). Program participation and spending patterns of families receiving government means-tested assistance. Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics.

Fox, L. (2018). The supplemental poverty measure: 2017. United States Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, Washington, D.C. (pp. 60–265).

Glied, S., Ougni, C., & Russo T. (2017). How medicaid expansion affected out-of-pocket health care spending for low-income families. Issues Brief, The Common Wealth Fund.

Grossman, M. (1972). On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. The Journal of Political Economy, 80(2), 223–255.

Grossman, M. (2015). The relationship between health and schooling: What’s new? (Working paper 21609). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gruber, J. (2000). “Medicaid,” (Working paper 7829). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Harberger, A. C., & Just, R. (2012). A conversation with Arnold Harberger. The Annual Review of Resource Economics, 4, 1–26.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2019). Where Are States Today? Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility Levels for Children, Pregnant Women, and Adults.

Levy, H., & Meltzer, D. (2008). The impact of health insurance on health. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 399–409.

Majerol, M., Tolbert, J., & Damico, A. (2016). Health care spending among low-income households with and without Medicaid. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Meer, J., & Rosen, H. S. (2004). Insurance and the utilization of medical services. Social Science & Medicine, 58, 163–1632.

Remler, D. K., Korenman, S. D., & Hyson, R. T. (2017). Estimating the effects of health insurance and other social programs on poverty under the affordable care act. Health Affairs, 36(10), 1828–1837.

Small, K. A., & Rosen, H. S. (1981). Applied welfare economics with discrete choice models. Econometrica, 49, 105–130.

Sommers, B. D., & Oellerich, D. (2013). The poverty-reducing effects of Medicaid. Journal of Health Economics, 32(5), 816–832.

Sommers, B. D., Gwande, A. A., & Baicker, K. (2017). Health insurance coverage and health – What the recent evidence tells us. New England Journal of Medicine, 377, 586–593.

Train, K. E. (2009). Discrete choice methods with simulation (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

United States Government Accounting Office. (2018). Medicaid expansion and access to care. GAO-18-607, Washington D.C.

Acknowledgements and Disclaimer

I wish to acknowledge Secretaries Brent Earnest and David Scrace, and Directors Julie Weinberg, Nancy Leslie-Smith and Nicole Comeaux in leading the implementation and administration of the Affordable Care Act through the New Mexico Human Services Department. I also extend my thanks to the University of New Mexico Department of Geospatial and Population Studies for including this work in the second Biennial Population and Public Policy Conference, in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Finally, I am grateful to Jason Sanchez, Jaclyn Herrera, Shane Shariff and anonymous referees for reviews and suggestions in the development of this work. That said, I assume sole responsibility for the hypothesis, method of analysis and reported findings of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ulibarri, C.A. (2020). Expected Consumer Surplus from Medicaid in a Prototypical Working-Age Household. In: Jivetti, B., Hoque, M.N. (eds) Population Change and Public Policy. Applied Demography Series, vol 11. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57069-9_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57069-9_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-57068-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-57069-9

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)